9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

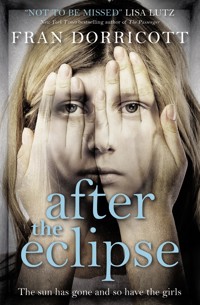

A stunning psychological thriller about loss, sisterhood, and the evil that men do, for readers of Ruth Ware and S.K. Tremeyne A little girl is abducted during the darkness of a solar eclipse. Her older sister was supposed to be watching her. She is never seen again. Sixteen years later and in desperate need of a fresh start, journalist Cassie Warren moves back to the small town of Bishop's Green to live with her ailing grandmother. When a local girl goes missing just before the next big eclipse, Cassie suspects the disappearance is connected to her sister – that whoever took Olive is still out there. But she needs to find a way to prove it, and time is running out.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

Acknowledgements

About the Author

The Final Child sample chapter

Also Available from Titan Books

AFTERTHE

ECLIPSE

AFTERTHE

ECLIPSE

FRAN DORRICOTT

TITAN BOOKS

After the EclipseUS print edition ISBN: 9781785657887E-book edition ISBN: 9781785657894

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: March 20192 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© 2019 Fran Dorricott. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

What did you think of this book?We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at:[email protected], or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website:

TITANBOOKS.COM

For Shadow, without whom this novelwould have been written two years earlier.

…and the sun has perished out ofheaven and an evil mist hovers over all.Homer’s Odyssey XX. 345

Prologue11 August 1999

THE DAY SHE BECAME a local legend, Olive Warren did not do as she was told.

Normally a well-behaved child, and as unlike her sister as it was possible to be, Olive hated to be told off. She liked quiet things: libraries, dinosaur bones in museums, her model of the solar system. People told her it was odd, but she figured if she wanted to be a curator, or even an astronaut, then liking rules and silence was probably a good thing.

Still, staying with Gran in the summer was never the same as being back at home in Derby. Here at Gran’s, rules were bendy and punishments were non-existent, especially when her older sister was in charge. And anyway, this was an extra special day.

She’d been looking forward to the solar eclipse for weeks and she wasn’t going to miss it because her big sister was too busy with her new “friend”. She’d counted down on her calendar, ticking off the days until the event, even when Cassie made fun of her. When the day arrived, they went to Chestnut Circle, the centre of Bishop’s Green’s universe.

There was a big party; the town seemed more alive than Olive had ever seen it, thrumming with the sense of possibility. Olive had been excited at the thought of all the people in town coming together to watch the eclipse – but the reality was overwhelming. The crowd was too thick, and although there was a stage and children playing party games she couldn’t see any of what was happening. Some kid won a large cuddly unicorn and all Olive saw was the rainbow mane and a spindly golden horn.

The music was too loud. Olive longed to be back at Gran and Grandad’s house, perhaps sitting on the roof outside the bedroom she shared with Cassie. She wished people would quieten down and just wait. Olive followed the minute hand on her watch. The main part of the eclipse was supposed to happen at ten past eleven but what if she couldn’t see it?

Cassie and her friend Marion were hanging back in the little alley next to the corner shop, their heads bent together, totally oblivious to everything. They were whispering, their noses almost touching, completely ignoring Olive. It had been like this between them for days now, but today was worse because Marion was meant to be going on holiday soon and neither of them wanted her to go. Olive decided she didn’t mind if Marion went. At least then she wouldn’t have to share Cassie.

Olive’s frustration boiled in her stomach as she watched them. She couldn’t decide whether to do it – to stretch Cassie’s one rule. Stay in sight. Her body was tense with the idea that she didn’t have to do what Cassie said all the time.

“Olive, stand still, will you? Gran said you’re meant to stay near me,” Cassie called.

Olive sighed. She’d only been trying to get a better view. She couldn’t see anything, least of all the sky, through the awning above the shop. They weren’t here for Cassie to get all moony with the policeman’s daughter. Cassie had even been grumpy when Olive went into the shop for a can of Coke even though she was only gone a minute and Gran had given her the money for it. It wasn’t fair.

In that moment, Olive decided. She was going to break the rules, not just bend them. It was only going to be the once, and it wasn’t going to be for very long. The crowd was pressing in on her, making her palms sweaty; even though nobody touched her she felt breathless. She just needed to see better. She needed what Gran called a “vantage point”.

Olive knew Folly Hill from the picnic her gran and grandad had taken them on the summer before. It wasn’t far, maybe a mile. Olive was good at walking, she enjoyed it, and Olive knew that from the hill she’d have a view to die for as the sun shimmered into darkness. She’d be able to see much of Bishop’s Green in its little dip between the green hills, would be able to watch as the shadows chased across the streets near her gran’s house. She could write her summer paper about it when she got back to school.

Plus she could probably get back before Cassie even noticed she was gone.

So she waited until Cassie and Marion were whispering again, hidden in the mouth of the alley. The candy-striped awning stretched around the side of the shop and they were huddled in the growing shade. They were so busy, so full of each other. Olive sort of wished she had a friend like Marion – somebody who just soaked up all of the badness and the arguments. Cassie never had to listen to Gran and Grandad talking about Mum and Dad and their problems; she was always on the phone with Marion, thinking about Marion. Talking about Marion.

Olive took the plunge. She sneaked out of the alleyway, skirting along the edge of the crowd and towards the road. There were a few cars parked beside the corner shop, stragglers coming late to the party in the Circle, but nobody paid any attention to Olive. The noise was growing from the people crowded around the fountain in the middle as the DJ on the stage gave a countdown. Half an hour to go until it was dark. Until the eclipse. Olive mouthed the word and felt the magic of it tickle her with excitement.

She’d been waiting for ages for this. She wasn’t sure if it would get totally dark here – Gran said it would be the best down in Cornwall – but they stood a decent chance since it wasn’t too cloudy. Bishop’s Green was the perfect place to watch it, really. A town soaked in its own magic. It even had the Triplet Stones – sort of Druid stones up on the hillside – which Olive loved. Visiting her grandparents here was like going on holiday back in time, to a world where people still believed in omens and spells and lucky charms.

The eclipse was the event of the year. Of the decade. Olive could already feel the moon on her skin as the shadows lengthened. Gran had told her that crescent moons were meant to be the most powerful lucky symbols, but Olive figured eclipses probably beat them since they happened so much less often. It would be years and years before there was another one.

As she headed away from the noise there was an eerie quality to the sound fading away, as though that too was being eaten alive. She felt like she was running out of time. Willow Lane, the road out towards Folly Hill was dusty and uneven. It was deserted, Olive realised, because everybody who had thought of going to the hill to watch the eclipse was already there. The lane was longer than she remembered, too. Olive’s chest was tight from the dryness of the air as she walked faster.

It must be gone eleven o’clock now. The dark was growing. She should have left sooner, should have been braver. Cassie was never going to chase after her. What had she been so afraid of?

She started to run. Slowly at first, a jog, but soon she was panting and running so hard her legs were going like jelly. She caught her foot in a dip, her knee crashing down and scraping the ground. She didn’t make a noise. She hated to cry.

Her knee stung like it had a thousand tiny scratches – and her palms hurt too. They were gritty with the gravelly white dust from the path, not helped by the Coke she had spilled earlier, or the segment of orange she had eaten in the shop, the juice still tacky on her fingers. She wanted to wipe her palms on her shorts, but that would only sting worse. A little hiss escaped from her mouth.

She got back to her feet, her ankle complaining and the skin on her knee stretching and creasing in all the wrong places. She wiped her forehead with her arm, glancing up at the sky. Not yet, she thought. Not yet, please. I don’t want to miss it.

Just then, somewhere behind her, she heard a rumbling sound. Willow Lane didn’t look like the kind of place that saw many cars. Or many people, Olive thought, except dog walkers.

She turned as a van approached up the long, steep lane, the hedge on the left rising up high above her and making the sound seem like it was coming right at her. She stopped walking, squinting to see if she could see the driver.

She couldn’t. Not at first.

The van slowed to a walking speed when it came closer. The driver waved. That’s when she recognised him. Now he came to a stop, wound down the passenger window and leaned across to speak to her.

“I saw you leave the party,” he said. “You heading for Folly?” He was wearing sunglasses hooked onto the neck of his shirt and a baseball cap like one her dad owned.

She nodded. The darkness was growing, like it was chasing them. She wanted to look upwards, to see the silhouette of the moon start to creep across the sun, but she didn’t want her eyeballs to burn because her special glasses were still in her pocket. It felt rude to get them out now. The shadows were getting longer though, and Olive wished she’d brought a jacket. The birds had gone quiet, and all she could hear was the rumbling of the van and the far-off sounds of celebration from the Circle.

“You’ll miss it if you don’t get a move on,” he said.

“I know.”

“I can give you a ride, if you want. Just up the hill.”

Olive thought about this, but only for a moment. She’d been told to never take a car ride with a stranger, but everybody knew everybody in Bishop’s Green. It was just that sort of place. Gran and Grandad gave Cassie and Olive the run of the town when they were here; Bishop’s Green felt like the seaside, everybody smiling and friendly. And she knew him well enough by now, didn’t she? It wasn’t like at home, where Mum was always telling them to be careful and not to talk to strangers.

So she nodded again.

He opened the door from his side of the van and she clambered inside. It was surprisingly chilly inside, a breeze blowing through the open windows. She shivered, the sweat cooling rapidly on the back of her neck. She was thirsty, despite the Coke she’d had earlier, which just made her tongue feel fuzzy in the heat of the day.

The man noticed and handed her a bottle of water. She took it gratefully; the coolness of the bottle on the grazed skin of her hands was soothing even if it stung a bit. She drank greedily from the bottle.

“Why did you leave the party?” he asked as they moved off. The van felt like it was crawling up the hill and smelled faintly of antiseptic. “You looked like you were having a good time earlier.”

“It was okay,” Olive said hesitantly.

“But then Cassie ruined it. She’s not really very nice to you, is she?”

Something about the man’s voice made Olive stop. Her heart fluttered nervously, although she didn’t know why. He was watching her as they drove up the hill, his gaze no longer fatherly.

“I…”

He’d been nice to her all summer – but now it didn’t feel like he was protecting her. The way he said her sister’s name made her shiver. The wrongness of it settled in Olive’s stomach along with the stale water and she squirmed uncomfortably. It was like something had changed, right here in the van. The air was too cold, the sky outside too dark. Olive was belted in and she didn’t like how the man seemed too close to her, how he smelled like antiseptic and somebody else’s clean clothes.

She realised she didn’t even remember his name.

Suddenly the silence was unnerving, the quiet she’d craved was too much. Olive wanted to stop the van. She wanted to get out. But she found that her mouth wasn’t working properly; her tongue felt heavy and she was pretty tired. Panic started to worm about inside her. He’d rolled the windows up. The van kept moving. Further away from Cassie, from Gran and Grandad. From everything.

The man kept looking at her. He drove faster.

And as the road grew darker, as the sun was eaten by the moon, Olive Warren began to wish she had just done as she was told.

1

Monday, 16 March, 2015

THE SUN WAS JUST rising as I headed out for my run but I had been awake for hours. My eyes were gritty. I could feel the long sleepless night behind me like a spectre and my whole body ached with it – but I focused on the relief instead of the tiredness. I listened to the steady pounding of my feet on the pavement, and then on compact dirt as I pushed away from the residential streets of Bishop’s Green and into the woods south of town.

I tried not to think at all, focusing on my breathing, my heartbeat, the ache in my legs. At least it wasn’t the job that was going to kill me these days. That could only be a good thing.

When I’d traded city life and the battle for a decent journalism gig in London for my grandmother in Bishop’s Green, I’d had visions of family dinners, of me playing the doting granddaughter who managed her grandmother’s dementia with ease. Instead I felt like a prison warden – and that was on the days when Gran remembered who I was. The days when she didn’t were harder still, having to explain who I was and why I always felt like such a failure.

I felt the itch even as I ran. The itch to call it quits, to hold my hands up and claim defeat. When I’d made the decision to leave London it had been on the back of a six-month rough patch. Losing my job had been hard enough – but that had been my own fault. The three-year relationship and the cushy London flat that I’d lost with it, however, still stung. But I shook the thoughts from my mind as I ran; it didn’t matter why I’d left, I was here now.

I let my feet guide me as the thud-thud of my trainers drowned out my worries. I cut away from the trail, brambles scratching my legs as I widened into a loping, unsteady pace and let my breathing go wild. This was my first run in over a week and I relished the damp air on my hot cheeks, sucking in the sweet scent of evergreens on the March wind.

The woods began to thin, and I passed a gnarled old tree with a rope swing on a low branch. It was the sort of thing Olive and I would have spent hours playing on during our summers here, although she’d probably have spent a good fifteen minutes trying to determine its stability first. I smiled at the memory.

I’d been thinking of Olive a lot recently. She was always there, a soft phantom at the back of my mind, but it had been worse in the last months. Moving back to the town where we’d last been together had seemed cathartic over a drink in a distant London pub. Now it felt misguided. Morbid, even. And I knew that the looming solar eclipse was only upping the frequency of the nightmares.

I didn’t want to think of my sister this morning. I was too tired, too emotional. Gran had managed to escape in the night, wandering the fields for hours before I tracked her down. Her midnight escapades were getting more frequent, harder to prevent. I just wanted to run, to get sweaty and think about nothing except my aching body.

I stumbled back onto the trail and followed it out of the trees, panting now with the effort. A grassy bank came into view, and I slowed for a minute, blinded by a sudden brightness. Hands on my knees, I came to a complete stop at the edge of the lake.

It was how I remembered it. Big, dark, stretched taut like blown glass. The sun, fully risen now, was a distorted disc among reflected clouds. There weren’t many people around yet but the weather wasn’t entirely to blame. The whole town had lost the bustle I remembered from my childhood summers here. Still, by August the tourists would be back, drawn by Bishop’s Green’s reputation as a magical hotspot, blessed by the Triplet Stones or Druids, or whatever nonsense they’d been peddled to reel them in.

I was about to turn for home when something further down the bank caught my eye. I angled back, spying a group of people gathered beside a crop of small trees. They were rapt, staring across the lake. Two women with pushchairs, a man with a dog, a young couple. All of them focused on the same thing, which I saw for myself as I drew closer.

A boat in the water. And, judging by the official-looking people inside it, I’d bet my last cigarette that they weren’t there for sport. I headed for the woman closest to me, my curiosity like an addiction. I never could shake it; it’s what had led me into journalism in the first place – that, and the victims.

“What’s going on?” I asked.

She half turned to me but kept her eyes fixed on the boat as it moved at glacial speed. I could hear its humming now, the wind pulling the sound towards us.

“That girl – the one that went missing on Friday. Nothing good ever happens on Friday the thirteenth, does it? God, I think they’re looking in the water. Her poor family.”

I felt my heartbeat stutter. I knew I’d been wrapped up with Gran, but how had I not noticed a child disappearing? The woman’s superstition wasn’t lost on me but I shrugged it off as the same kind of silliness the whole of Bishop’s Green thrived on. I noticed that there were more people on the other side of the lake now. A few policemen. Dogs.

“She’s only, like, eleven.” The woman made a noise in the back of her throat. “This shouldn’t happen here. Nothing like this has ever happened here.”

I stopped listening, the blood roaring in my ears. A missing girl. Here, in Bishop’s Green. The sun was suddenly blinding, a hot white circle in my eyes. When I blinked, black spots eclipsed my vision just like in my dreams. An eleven-year-old girl – missing.

I didn’t correct her. Couldn’t bring myself to speak. Instead I ran away, back towards town and home. The home that I’d hoped would be a fresh start.

The woman on the bank was wrong. Something like this had happened here before. Sixteen years ago it happened to my sister.

* * *

At home I made myself busy. Coffee on, laundry in the machine, and breakfast on the table in record time. I did the jobs I’d been avoiding, too. I made Gran’s check-up appointment with her GP and even willingly spent ten minutes on hold to the adult day centre to rearrange a taster session. Adult jobs completed, I’d just settled down at the dining-room table with my mobile when the landline rang.

“Cassie, darling. How’s it going?” My frayed nerves were soothed by Henry’s familiar voice, gravelly from years of cigarettes and still betraying his Cornish roots despite three decades in London. It was good to hear from him. “How’s northern living?”

“Still only in the Midlands,” I replied. The same answer I’d given every time he’d called since I moved here two months ago. To Henry, anything north of the Watford Gap was northern enough. He still couldn’t believe I’d gone through with it.

I could tell he half expected me to give up and head back to the anonymity of the city. And if I didn’t come home of my own accord, he was determined to convince me. As if going back there, with no home and no job, would still be better than this.

“You sound shattered,” he said. “Are you sleeping?”

“I wish.” I rubbed my hand over my face and sighed. “I was out all night looking for Gran again. I don’t know how she keeps doing it. I hid the key last night and she still managed to get out. I found her wandering about in a bloody field at just gone five this morning. She was frozen.”

“Christ.” Henry paused, a tapping sound on the receiver warning me that he was about to say something he thought I wouldn’t like to hear. “I know you’re not close to your dad, but can’t he help you? It seems like a lot for one person to deal with, even with carers popping in during the day. This always seems to happen at night. I know you said they’ve assessed her and she’s okay to be at home but—”

“Dad wants to put her in a home, Heno. He’s no help. She’s not his mother so I don’t expect him to be. I just don’t want that for her – not yet. She was always such a rock, you know? Especially after my mum died. I can’t lock her up in one of those places without exploring our options first.” I didn’t say that living here with me as her jailer was hardly much different, but Henry seemed to sense it.

“Is she all right now, anyway? After last night.”

“She’s fine. Asleep again. Like I should be.”

“Go to sleep then, darling. I’ll call you later.”

I didn’t want Henry to go. After this morning, seeing the police on the water like that, I was rattled and I needed to hear his voice for a while longer. He had been an excellent mentor when I’d moved to London a decade earlier to begin my career in journalism, but over the years since he’d made an even better friend. He’d retired last year and still read all of my articles before I submitted them.

“Can’t sleep now. Too much caffeine in me,” I said. “Too little booze. Don’t know why I thought moving here would be a good way to learn to be an adult.”

I started to laugh but stopped myself.

“Spoken like a true millennial,” Henry said.

There was a tense silence. Something unspoken in the air between us that sounded like, “At least you’re not using the sleeping pills any more.” Henry knew I had a tendency to self-medicate when I got stressed, but I hadn’t told even him how bad it had become when I’d first moved back to Bishop’s Green. It turned out that sleeping pills, which had always been my go-to way of switching off from the world, were a terrible choice when pitted against Gran’s Houdini act. They made me groggy when I needed to be able to keep up with her disappearances. Now I didn’t like to have them in the house.

But considering how little I’d been sleeping before my grandad died two months ago, and how the loss of my job might have had something to do with the three double brandies I’d consumed before decking the sexist bastard I was meant to be interviewing, it was probably better not to joke about the fact that I’d switched back to the booze. Honestly, it was lucky I’d only lost my job. If the guy had pressed charges I’d have been much worse off and a drink here and there would have been the least of my worries.

“You’ve got to get out of that house more, Cass,” Henry admonished me finally, his voice deliberately light. “You sound like you’re going stir-crazy. I knew you would. You’re not meant to live in a cage.”

“I’ve been out all morning.”

“You know what I mean. You’re a hack. No good hiding from it. You live for the story. Keeping yourself all cooped up in that house won’t make you feel any better about the situation with your gran. Get yourself a job and things will seem brighter.”

“No. You’re right.” I watched through the dining-room window as a flock of birds flew overhead. The sun seemed too big in the sky. Too bright. I thought again of the upcoming eclipse and then shook my head.

“Did you hear about the missing girl up your neck of the woods?” Henry asked, obviously realising he’d upset me. This was his peace offering. “Seems like your sort of story. You’d have dived at it if it were down here. I know you haven’t been writing since you left London but this might be good for you. I’ll read over anything you send me.”

I’d had the news story open on my mobile even before Henry mentioned it. Like a scab I couldn’t stop picking at, it had been calling to me all morning. And the more I tried not to think about it, the worse it was. But I wasn’t sure I was ready to start writing again yet, ready to put myself back into that world.

“Not interested,” I said. But I kept the article up, and I couldn’t banish the curiosity from my voice. This girl – her name was Grace – was the same age Olive had been. The coincidence made me nervous.

“Liar,” Henry said. “Doesn’t look like the family have been interviewed yet. You should get in there. Try to get an exclusive with the mother—”

“Not. Interested.”

“You’re so bloody stubborn.”

“No I’m not,” I said. But I couldn’t help smiling. Henry was right. It was the sort of story I’d have leapt at before now. When my own sister was taken I’d hated the reporters who swarmed my family, but as I got older I’d become determined to be a voice for the victims, not a sensationalist. It was an attitude that had made me as many friends in the business as it had enemies. Most hacks didn’t like that I referred to them – to us – as vultures. And meant it.

The missing girl, according to the article on my phone, had left school at half past three on Friday and hadn’t made it home. No note, no indication that she was going anywhere. None of her friends knew anything. I scrolled down the article with the tip of my finger, itching for more information, when Henry’s gravelly chuckle brought me back to my senses.

“All right, you’re not stubborn,” Henry said. “But I do think it would do you good. Give you a bit of focus. And anyway, it’s an excuse to go and see—”

“Don’t say it,” I grumbled. “I haven’t seen her since her dad’s funeral, Henry. That was two years ago. Why would she want to see me now? It would be too…”

“Awkward? Come on, darling. I’ve heard the way you two talk on the phone. She can’t get you to shut up. She’s your Juliet.”

“Oh God. Don’t start that again. Just because you’re super into gay marriage doesn’t mean I have to be. Besides, it didn’t exactly work out for the best for Romeo did it? I’d rather stick with Rosaline.”

Henry let out a barking laugh but didn’t press me any further. We chatted for another few minutes and I could almost pretend that I had everything under control.

Then Henry said, “Helen asked about you, you know. I told her you were okay. She seemed glad.”

The pit in the bottom of my stomach opened right up and I thought my heart might fall in. I swallowed. Truthfully, it didn’t hurt that she’d dumped me as much as it hurt that she didn’t think we could stay friends. That, and the flat I’d lost when she said it. Moving to Bishop’s Green had seemed like a good way to start over, to move forward, to stop wallowing and do something different, but I’d forgotten how isolating it could be here. How lonely. I hadn’t even told Henry that my only friend in town was the guy who sold me coffee, and he was a good twenty years older than me.

“Thanks,” I said softly. “Yeah, I’m okay. Talk later.”

I hung up, pushing down the frustration. My gaze fell on my phone again, and I caught sight of the photograph in the article. Grace Butler’s face was round and pink and scrubbed clean for a school picture. Blonde hair, blue eyes. She was positively angelic.

MISSING.Pictured: eleven-year-old Grace Butler, who disappearedon her way home from school on Friday, 13 March.

A growing sense of unease filled me as I read the article for the third time. Her stepdad, Roger Upton, was pictured as well, looking dishevelled and distraught.

She’d been missing two days and they were already dragging the lake. Christ. I shook my head and pushed back the awful memory of that other time, sixteen years ago. Men on the lake, boats, a crowd gathered at the edge of the water.

I’d watched it unfold on Gran’s television set, shaking and unable to believe that it was real. That it was happening. That Olive wasn’t going to walk into the bedroom any moment and complain that I’d hidden her library book, and our summer holiday with Gran and Grandad wasn’t going to go right back to being boringboringboring.

The memory gripped me tight. I saw the relentlessly blue sky – not even the decency of rain. The wind barely stirring the trees around the lake. The woman on the screen tolled a number that was growing and growing. A hundred and forty-six hours since the eclipse. A hundred and forty-six hours since she’d vanished. A hundred and forty-six hours since I’d made the worst mistake of my life.

And now it was happening again.

2

THE ROOM THAT WAS now my bedroom had once been my grandad’s art studio. The walls were still decorated with the little four-leaf clovers he had believed to be so lucky. I still sometimes caught a whiff of acrylic paint, or turpentine and dusty brushes, although I’d cleared most of his stuff into the attic when I moved in after the funeral two months earlier. It was a comforting smell, one that reminded me of him and his warmth.

The spare bedroom was bigger than this one. Twice as big, actually, with a better view of the garden. But I hadn’t touched it. It had been the room Olive and I used to share – and although it had been redecorated at some point I still saw the bunk beds and lava lamp. And a small part of me still feared the ghosts of Olive and myself that might haunt it.

I settled down at the desk in my poky little room with a fresh cup of tea. I couldn’t stop thinking about the missing girl, Grace. And about Olive. What were the chances of two little girls the same age vanishing sixteen years apart in the same town? Probably quite high. Bishop’s Green was bigger than it looked on first glance. It was a warren of residential streets around a central hive, a town that still believed it was a village, the fact remained that it could easily be a coincidence.

But we were due another solar eclipse and that set my teeth on edge, my journalist brain making all sorts of phantom connections. The timing was too much of a coincidence – more of a coincidence than anything else.

They’re not connected, I told myself. They can’t be. Olive was taken during a public event. A chance abduction during the minutes of murky twilight, everybody too busy counting omens or waiting for the do-over the eclipse had promised them. I tried to think clinically. This Grace kid, she just hadn’t come home from school. She might even be a runaway, although eleven was a bit on the young side. Perhaps she had fallen out with her friends, her parents; perhaps she had simply been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I bit my lip. The box in front of me on Grandad’s old desk was battered, the Dr. Martens logo on the side badly faded. Its corners were crushed from years of being shoved about inside my wardrobe and the lid was caked with a layer of dust.

I always took it with me when I moved. It had followed me from Bishop’s Green to Derby, and then to Sheffield and York and then London. And now back again, full circle. I rarely opened it, and when I did it was usually to shove some other painful Olive-related memory inside.

Now I wanted to look. Needed to, even. Maybe it was like Henry said – I needed a distraction. Or validation. I wasn’t sure.

I took a shaky breath and lifted the lid. Inside, it was exactly as I remembered, filled with photos and stickers, writing on napkins and even a couple of newspaper articles, folded into yellowing squares. There was a birthday card Olive had made me. One I’d told her I’d ditched.

I sifted through pictures of Mum, me and Olive. Dad, always behind the lens, had captured us on the beach, at Christmas, at the park. The photos were familiar, worn by my teenage fingers. The ones of Mum were the most faded, all of them taken in the years before Olive was abducted. Back when Mum was still her strong, occasionally smiling self.

I picked up one of Olive on a roundabout, and beneath it was one I’d found on Grandad’s noticeboard of me and my sister in the garden right here in Bishop’s Green. It must have been taken the summer she was abducted. We were on the verge of hysterical laughter as Olive accidentally swore at the camera as she tried to make Ginger Spice’s peace sign. I looked away, the image of Olive frozen in the nineties with her Buzz Lightyear T-shirt, friendship necklaces and platform trainers making my eyes begin to itch.

This was stupid. I was only going to upset myself. I started to put the things away, organising them carefully, until my fingers brushed the journal at the bottom of the box. I felt a shudder of something. Anticipation? Fear? I didn’t even know why I’d started looking but now I couldn’t stop.

This was my “Olive Diary”.

The psychiatrist I saw after Olive disappeared suggested I keep a journal. She didn’t know that I already had one. I was sure if she’d known the sorts of things I’d filled it with she’d have changed her mind about it being good for me. It was filled with my loopy fourteen-year-old scrawl, stuck throughout with newspaper clippings and other bits of paper. It had been an obsession.

I flicked through and my fingers came to rest on a page almost of their own accord.

I read in the library that most child abductions happen because of family. The police aren’t looking for a stranger for Olive. Why?? Mum was at work. Gran was getting her hair done. Grandad was at the vet’s with Molly. That leaves me and Dad.

And then there was a question. Biro scrawl, shaky and smudged out of shape.

DAD. Where was he?

I sat back, my heartbeat in my throat and my hands starting to sweat. I remembered the damp hotness that preceded the writing of this note. Too many people crammed into my grandparents’ house – too much crying. I was sitting on the floor outside the kitchen, knees to my chest. Mum and Dad were out of sight but I could still hear them.

“You have to tell me where you were. You owe me that much at least.”

“I don’t owe you anything, Kathy.” My dad’s voice was taut, tired, the secret eating him up. “How can you think I had anything to do with this? How can you think I’d hurt her?”

“How can I not? You won’t tell me anything.” A pause. “Did you hurt her?”

“No.” Not an exclamation. A weary statement of fact. The same answer to the same question.

“Tell the police, then. They know you’re lying. Cassie knows. I know. At least tell somebody.”

“It’s not that simple.”

“So you are lying, then.”

“Fucking hell, Kath. This isn’t my fault. Cassie was meant to be watching her.”

I hadn’t been able to stop myself. The kitchen was hot and the windows fogged with the endless heat Mum kept blasting because she was cold all the time. I marched into the room, whole body shaking.

Before I could stop myself I was howling.

“I didn’t mean to. I didn’t mean to! I told her to stay where she was—”

“Don’t you blame her. Don’t you dare blame her!” Mum was shouting too. She moved to put her hand on my shoulder but I couldn’t bear it. Couldn’t stand the thought of being touched because it seemed like the grief had pierced every inch of me and even my skin ached.

Dad didn’t move, frozen in the corner, arms straining against the counter behind him as though he was having to hold himself back.

“Where were you?” I screamed at him.

He didn’t speak.

“It wasn’t her fault,” Mum repeated. Over and over. “Not her fault. She’s all we’ve got.”

Dad and I stared at each other. My breath heaved and with every movement I thought I would be sick. Because it was my fault. Even Dad thought so. And although Mum hadn’t said it, I knew the only reason she didn’t blame me, couldn’t blame me, was because then she would have to agree with him.

I’d felt myself get hollower and somehow heavier too as I stormed out and then slunk up to my bedroom, sickness churning in my belly.

Dad hadn’t answered the question. Where had he been? Could he have hurt Olive? He hadn’t been at work like he’d said. The police had told us.

By the time I’d written Dad’s name in my diary I knew things would never be the same again. He’d known it, too. He had seen the doubt in my face. There were no words that could change what had happened between us, that fracturing, splintering – even after the police cleared him. It wasn’t about truth, it was about guilt. I felt guilty for losing Olive, and he felt guilty for it too.

Then he moved out. And that was the last time Mum ever stood up for me – or did anything that might have been considered warm or passionate, or anything much at all.

My mouth had grown dry. I swilled cold tea around my teeth with a grimace, realising with a jolt that I’d been looking in the box for a sort of confirmation – about my own instincts. I’d known something was up with my dad long before my mum had. I’d known Dad hadn’t been telling the truth about where he’d been, what he’d been doing on days when he was meant to be working even before Olive was taken, but I’d never listened to my gut. In fact, I’d gone out of my way to pretend that I hadn’t noticed.

Even if he hadn’t hurt Olive, Dad was guilty of lying. And the feeling I’d had about my own dad was the same sort of feeling I got when I looked at the picture of Grace Butler’s stepfather.

He had a secret.

I knew, suddenly, that Henry was right. It was too late to pretend that I wasn’t interested in Grace’s disappearance. Because I was interested. I couldn’t let a good story go without at least a quick look, especially a story like this one. And I couldn’t live off the money Grandad had left me for ever.

And, dammit, that meant that there was somebody I needed to speak to about a job.

* * *

Marion’s house was almost identical to the one I shared with Gran, right down to the dry-stone wall out front and the lace curtains in the window. She’d inherited it when her father died and it didn’t look like she’d changed much.

I sat in my car for several minutes working up the courage to go and knock on her door. Just like I’d been putting off driving over here all day. I felt like a teenager again, my palms sweaty and my heart racing. It had been two years since I’d seen Marion – actually physically seen her – and now I didn’t know why I’d let it go this long.

Just as I was about to suck up the courage to get out of my car, I saw Marion’s front door open. Out stepped a dark-skinned man in a suit, smart white shirt and a red tie that flapped in the wind. I saw a hand reach out – Marion’s – to squeeze his shoulder. Then he cut across the drive and passed my parked car on the way to his.

I told myself that it didn’t matter – that he was probably a colleague and anyway I didn’t have the right to be upset when I hadn’t seen her in ages – but the sight of Marion touching somebody in such a familiar way made my stomach lurch. And she hadn’t told me about him when we last spoke. Did she want to hide him from me? Was she embarrassed – or concerned I’d ruin it for her?

When I finally made it to the front door, I was so wound up that I’d forgotten everything I wanted to say. And I had no time to compose myself because suddenly, there she was, door open wide and a small smile on her face.

She looked good. Really good. Her dark hair was pulled back into a messy bun and her fringe was just that little bit too long. She’d probably only been home from work for an hour or so, probably having a drink with him, and she was dressed in a creased white shirt and black trousers. I noticed that she still wore the necklace I had bought her. A little golden acorn – an amulet that in Norse folklore had symbolised luck and protection, the oak tree immune to the lightning and wrath of Thor. I didn’t believe in that sort of rubbish, but Marion had spent too long in Bishop’s Green and the town’s superstitious nonsense had well and truly claimed her.

The last time I’d seen Marion had been at her father’s funeral. I’d come to town just for that. We were both emotional. Marion’s dad was her only family. I’d just had my first massive fight with Helen and I wasn’t good for anybody, much less somebody who was grieving.

We hadn’t had words as such but I had too much to drink at the bar after the service and ending up puking in her kitchen sink, which was probably the low point of my year – although it wasn’t the first or the last time during that year that I drank too much. After that we stayed in touch by email and still had regular phone conversations, but I was more careful. She at least couldn’t see me doing anything that stupid again.

Now I was surprised to see the lines that had crept in around the corners of her eyes. They made her look more sophisticated – more grave, somehow – than before.

“Hi, Cassie,” Marion said simply.

I was overwhelmed by a rush of warmth, and then embarrassment. I was still a mess – a sober mess this time, granted – but Marion looked impeccable. High cheekbones, strong jawline, brows perfectly groomed; she was sleek, almost cat-like; her eyes, bright blue ringed with steely grey, sparkled with kindness.

“Your fringe is too long.”

It was the first thing I could think of to say. I saw Marion reach up self-consciously, but she smiled anyway.

Two years. For two years we’d been dancing around the subject of me coming back to town to visit. And I never had. Yet here I was, without warning, living only a few streets away just like when we were kids. Marion didn’t look surprised.

“Do you want to come in?” she asked. I didn’t want to. My heart was thudding and I felt like I might puke. But I also did want to – very badly. So I nodded and followed her inside, trying not to think about the man I’d just seen leaving. I couldn’t imagine Marion with a boyfriend. I knew that time changed people but she’d never been particularly interested in men. Especially not the clean-cut type. And she never dated colleagues or Suits.

“I did wonder when you’d finally screw up the courage.” I saw her lips twitch as she led me into the dimness of her lounge. “I’ve only been waiting six weeks. I saw you at the police fundraiser last month with your gran.”

I avoided meeting her gaze. I hadn’t realised she’d seen me. I’d done my best to duck for cover, heart hammering in the way of a nervous teenager. I tried not to look sheepish now, but the warmth in my cheeks belied my embarrassment.

“Sorry,” I said.

Marion shrugged.

“I’m sorry I missed your grandad’s funeral,” she said. “I know he meant a lot to you. I just didn’t think it was my place to show up out of the blue.”

It was my turn to shrug. I hadn’t expected her to be there. I hadn’t told her it was happening, and although she could have found out the date I wasn’t surprised when she hadn’t shown up. Now I didn’t know why I’d shut her out.

“It’s okay,” I said.

The lounge was crowded with travel knick-knacks that had belonged to her dad. On the mantelpiece there was the Statue of Liberty in miniature, her torch alight with a colour-changing rainbow flame. Next to her was a snow globe from Cornwall with two busty ladies on a beach. And on every surface there were elephants: statues, cushions with elephant embroidery, artistic photographs of elephants bathing, even a little plaque above the door. Elephants. More elephants than you would think could fit in one room, symbolising wisdom, power, loyalty – and overcoming death. These didn’t belong to Marion’s father.

Marion noticed my gaze.

“For the Hindu god Ganesha,” she said. “The remover of obstacles.” She gestured to the sofa. “The kettle’s actually just boiled. Sit and I’ll get you a cup of tea.”

I sank onto the sofa, hands between my knees, frustrated by how awkward I felt. It wasn’t like we didn’t know each other. I had often thought that I knew Marion better than I knew myself. But our friendship had been virtual for a long time; emails, text messages, phone calls – no substitute for the real thing.

I thought back to the summers I’d spent here, the long weeks with Marion out in the fields or hanging around Earl’s café for cheap hot chocolates or sundaes. It had been our yearly ritual – Olive and me. Summer in Bishop’s Green with the grandparents while Mum and Dad stayed at home so they could work. We’d loved it; the freedom, the seaside feeling of this landlocked town with its amusement arcades and ice-cream shops right down the middle. Its obsession with symbols of luck and prosperity. The fact that you could walk pretty much anywhere in less than an hour.

And Marion, the policeman’s daughter, who knew all the short-cuts, the best places to get two-penny sweets in great big paper bags, and which arcades had the best win-lose ratios. She always knew which department stores were having closing down sales, which boutique was flavour of the month, and which film screenings we could sneak into without being caught.

She was the prettiest girl I’d ever seen.

When Marion came back into the room, I jumped. She was carrying two cups, and she handed one to me. I wanted it to be like no time had passed, wanted for us to be able to talk easily, but the years stretched between us.

“I knew you’d come if I waited long enough. You’ve been ignoring my emails.”

I had. Since moving to town, I’d put off answering anything that wasn’t urgent. I’d pretended it was Gran, that I was busy, but it wasn’t true. I actually had a lot of free time.

“I’m going green,” I said. “Less tech. More… Zen.”

Marion laughed. “I get it. I’m terrifying.” She narrowed her gaze. “You look tired. Is it – stuff with Helen? I know you were feeling a bit down when we last spoke…”

I shrugged but I knew she wasn’t being mean. She was reminding me that it had been weeks. That I’d been avoiding her since I told her I was thinking about moving to town. It meant she’d been waiting for me.

“No,” I said firmly. “I haven’t spoken to Helen since I moved out. That’s all over. More than over, actually. It’s just Gran. I’m trying to get a better care situation in place. Grandad was doing so much for her and it’s just exhausting.”

Marion put her cup of tea down and my heart stuttered as it looked like she might reach over and touch me. But she only straightened some magazines on the coffee table. I exhaled.

“I’m sorry,” Marion said. “If you’d told me I could have given you a hand or something. I don’t know. Still, I’m glad you’ve finally come.”

“Did you miss me?”

“I missed having an excuse to check my emails at work.” She smiled again. “But anyway, I get the feeling that you’re not here just to see me. What brought you out of the Cass-cave?”

I was about to deny it, but I couldn’t. Even after all this time, she’d know. I never was a very convincing liar.

“Grace Butler,” I said. Marion didn’t flinch exactly, but something about her body language changed. Banter aside, I could see that my being here had affected her, and so had the missing kid. But I’d already said it, so I continued, “She’s been missing for a couple of days, hasn’t she? I wasn’t going to bother you – but then I saw that she’s the same age that Olive was… Anyway, I got interested.”

“You know I shouldn’t discuss it, Cassie, even with you. I could get in trouble.”

“I’m just intrigued. I don’t know. I was thinking about writing something. It’s just with Gran, and the eclipse coming up in a few days… I’m a bit antsy. I mean, they’re dragging the lake. That’s kind of a big deal.”

I thought of the poor girl’s parents, having to watch it all happen, powerless to stop it or to help. I felt my insides clench, as they always did when I thought of the families.

“Do you have any leads?” I asked.

Marion sighed. Shook her head. “She’s been gone two days and we’re not getting anywhere. Plenty of leads but nothing is panning out. A lot of people are trying to help, organising searches and things, but we have to consider the worst while hoping for the best. You’ve spoken to enough families in the aftermath of things like this. You know how it goes.”

Marion exhaled again, and I saw that her knuckles were white when she picked up her cup. I started to get up.

“Sorry. I’ll go. I didn’t want to pry. I realise it’s early days.”

“No, Cassie. Wait.” Marion didn’t move to stop me, but I heard an urgency in her voice and when I looked I saw a flash of indecision in her face. “I know it’s rough for you. I’ve been thinking about Olive a lot lately, too. Especially with the eclipse. But do you think this is for the best? Grace Butler isn’t your sister – I don’t know if it’s a good idea for you to connect—”

I tried to fight my growing frustration.

“Come on, Marion,” I said. “You know me. The personal touch is what people want. They want to feel like they know them – the family, the police. Those people out there, helping you search, they want to know who they’re helping. All I’m asking is for a bit of info. And I’m a bloody good journalist.”

The more I talked to Marion, the more I realised that I wanted to do this. To get my life back. To claw back my reputation, make a living. To help find that little girl and bring her home.

“If I don’t agree, you’re still going to do this, aren’t you?” she asked.

I faked a grin. “Yes.”

“Look… I can probably put in a good word for you with the family. Strictly a suggestion. They’re not speaking with a lot of the press – but I know they’ve been looking for somebody to write something. I wasn’t going to get involved with that side of things, but maybe I can make an exception for a bloody good journalist.”

This time my smile was real. I took in Marion’s wiry strength, trying not to let my gaze linger. It would be good to have an excuse to see her again, too.

“Just be careful though, will you? This is sensitive. I don’t know if you remember what it’s like here, but… it’s not like London. People are softer. They won’t want an outsider digging around. Just wait for me to set this interview up, okay?”

I nodded, but didn’t agree. Marion was half right: this wasn’t like London, but people here weren’t soft. I remembered that much from Olive’s disappearance. They might be more subtle than city people, but they would fight tooth and nail to protect their own. To keep their secrets. Perhaps even if it meant that another little girl never came home.

3

Tuesday, 17 March 2015

THE NEXT MORNING I headed to Ady’s corner shop on the Circle. It wasn’t far from Gran’s, and despite the prices being a little higher I never had to queue inside and Ady was a real stickler for keeping the shop pristine. Besides, it reminded me of my grandad, who swore there was something better about the cigarettes behind the counter than any supermarket in a ten-mile radius.

Ady had only just opened as I entered and he still looked half asleep. His grey-brown curls were wild, his warm eyes crinkling at the corners. He was fixing flyers to the noticeboard behind the till, where his daughter was sitting with a colouring book. Ady didn’t allow her to have a phone yet because she was only just out of primary school, and there was something refreshing about her old-fashioned creativity instead of mindless scrolling.

I scanned the wall and saw a flyer for a fun run Ady was hosting in a couple of weeks for the local RSPCA, and another for a jumble sale at the church. Today was St Patrick’s Day and there were several posters adorned with four-leaf clovers and cartoon leprechauns. Then one that made me shudder: an invitation for people to enjoy tea and cakes in the garden at Earl’s café while watching the eclipse on Friday.

Suddenly I could taste heat and sweat, the scent of fruit in the air as I remembered the darkness, the silent birds, the silvery sky. Blinking, I swore I could still see the crescent burn pattern behind my eyelids.

“Morning.” Ady’s daughter, Tilly, was dressed in school clothes, her white shirt so wide on the shoulders it looked like a tent. Her short blonde-streaked hair was pinned back with a brass clip in the shape of an owl.

“Hi. Nice hair clip,” I said, wiping my slick palms on my jeans. I was terrible with kids, but I actually tried with Ady’s daughter because he was probably the nicest person in town – the only one to date to make me feel welcome in Bishop’s Green. Most people seemed to have a sixth sense for Londoners in their midst and acted accordingly. “Those were all the rage when I was a kid. You look pretty.”

“Thanks,” she said awkwardly, reaching up to touch it, knocking her glasses with the tip of her thumb so they sat crookedly. A green four-leaf clover ring on her finger caught the light. “It was my mum’s. Dad’s really into them. Owls, I mean. For like… wisdom and that.”

Ady’s wife had died when Tilly was a baby. I didn’t know what to say so I grabbed the newspaper I had come for, Grace’s face smiling up at me.

“I’m going out to look for her after I close up,” Ady said when he noticed my gaze. He stopped to straighten Tilly’s crooked glasses and she waved him away. “There are a few of us going to walk the path behind her school – Arboretum Secondary. You should come. We need all the manpower we can get.”

“That’s nice of you,” I said.

“I’m always nice.”

I laughed weakly. “Sure you are. I’m just not sure I’ll be much use. I’ve been thinking a lot about my sister lately. Trying to remember. Grace being missing is bringing up a lot of stuff. A lot of questions about Olive and what happened to her. Do you… remember anything?”

“I’m sorry,” Ady said awkwardly. “It was a long time ago.”