Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

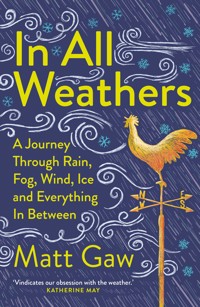

From the howling winds of Skye to the fen-sucked fogs of East Anglia, explore the power and beauty of British weather in all its wild and stormy forms. 'Beautifully written, wonderfully immersive and utterly life-affirming. This book glows with a rare light.' Julian Hoffman 'In All Weathers pulls off the trick of shining a fresh light on our much-maligned climate'Mail on Sunday 'In his glorious ode to the inclement, author and teacher Matt Gaw reveals how all weathers transform our relationship with the natural world – the secret is to open your senses and immerse yourself'The Observer magazine All too often our weather is simply deemed as good (sunny) or bad (anything else), and our likelihood of venturing outside is governed by that simplistic judgement. But inclement weather can be beautiful, sublime, even fun. It transforms the light, textures and colours of a landscape and influences our mood and behaviour. It has inspired poets and artists, seeped into our language and folklore, and fundamentally shaped our way of life on these isles. It allows new worlds to emerge, shrouded in fog, splintered by ice and refreshed by rain. In In All Weathers Matt Gaw embarks on a series of walks across Britain – through rain, fog, wind, ice and snow – to look again at our most widely accessed experience of the natural world, exploring where our weather comes from, the ways it is changing, and how we can embrace it as a positive presence in our lives. It's time to throw open the doors, window and soul to the inspiring wildness of weather. 'Gorgeously immersive and exposing. Matt Gaw's writing is lucid and illuminating, but with a subtle sensuality and creatureliness that means we almost walk in his skin. A journey of reconnection when we have never needed it more.' Amy-Jane Beer, author of The Flow 'In All Weathers is a beautiful book, a shimmer of unexpected ways of seeing and experiencing the world, shining with detailed insight and attentive understanding. Wild, oppressive and inclement weathers have found a wonderfully gentle champion in Matt Gaw – these are explorations to delight every walker and refresh any reader.' Horatio Clare, author of Heavy Light 'Elegant, learned and thoughtful, this book vindicates our obsession with the weather.' Katherine May, author of Enchantment 'Matt's vivid, personal journey through weather will inspire you to welcome and embrace even the dullest, dampest, shiver-inducing-est of conditions. Uplifting and full of wonder.' Lev Parikian, author of Taking Flight 'A brilliant, bracing, elucidating book. Wonderfully researched and written.' Stephen Rutt, author of The Eternal Season

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 288

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘In All Weathers is a beautiful book, a shimmer of unexpected ways of seeing and experiencing the world, shining with detailed insight and attentive understanding. Wild, oppressive and inclement weathers have found a wonderfully gentle champion in Matt Gaw – these are explorations to delight every walker and refresh any reader.’

HORATIO CLARE, author of Heavy Light

‘Matt’s vivid, personal journey through weather will inspire you to welcome and embrace even the dullest, dampest, shiver-inducing-est of conditions. Uplifting and full of wonder.’

LEV PARIKIAN, author of Taking Flight

‘A brilliant, bracing, elucidating book. Wonderfully researched and written.’

STEPHEN RUTT, author of The Eternal Season

For my family and my friends

CONTENTS

Prologue

RAIN

FOG

ICE AND SNOW

WIND

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Notes

Index

PROLOGUE

WEATHER. UNWEDER.Suffolk, August 2022

It is late afternoon and my wife Jen and I are in the garden. The heat is dirty and still; the air warm as blood. We lie on a rug that we have pulled half into the shade and look up into a pale but cloudless sky. I’m looking for swifts. It has been a couple of days since I have noticed them scything and flickering around the houses in our street, screaming at the sun. I wonder if they have gone, and if that means the weather will finally break. Although it must be around 5 p.m., the sun is still fierce. I can feel the skin on my face blurring with sweat as I scan the skies again. Jen is squinting. She says the light feels strange, like when you’ve screwed up your eyes too tight and then, when you open them, everything is bleached out. As if the world has become an old photo.

I cover my eyes with my arm and think about the weather. The temperature has been stuck on at least 30ºC for two months now. Ceaseless. Heavy. At its worst, it is like the heel of a hand on the top of my head. It tightens the skin around my collarbone until it pinches; presses down with hard fingers on the bridge of my nose; makes my skull feel as if it is overflowing with something gloopy, thick and hot. It is a heat of bright, sickly colours. Split custard yellow. Curdled white. Jags of red. I can’t remember a summer like it. There have been heatwaves, yes, but this? The UK’s first red warning for extreme heat came on a glowering July day, when the air and land trembled under a greasy thumb-streak of haze. The temperature reached a record 40.3ºC. It was not warm. It was not beach weather. It was a rail-buckling, road-melting, spit-sizzling assault.

July 2022 will subsequently be named as the driest on record for East Anglia, the driest since 1935 for the rest of England. Now it is August and the consequences of the prolonged heatwave are all around. Many of the trees have dropped their leaves. In the hedgerows, the sloes and berries have shrivelled before they could swell. Ivy snaps between fingers like burnt crisps. The rivers have retreated. In places, the flow of the Lark and the Linnet disappeared upstream. The wet ditches, the ponds, have all gone. The only water comes from the farmers’ pumps that arc in long hissing tuts across fields full of burnt crops and cracks wide enough to fit your hand in. On our walks – taken only in the evening and with decreasing frequency – we have noticed dead birds. Blackbirds, thrushes, tits, rooks, jays and magpies. Some are victims of thirst and starvation, but all are signs that something has stopped. The saprophytes – those soil-dwelling organisms that feed on the dead and decaying – cannot function in the moisture-free soil. The creatures that fall do not rot as they should, but stay intact, along with knotty strings of fox scat baked white as bone.

Even now, with the temperatures back to around the seasonal average, it still feels unbearable. The heat squats in rooms long after the sun has gone down. It puffs off furnishings and furniture like dust. The air creeps like lava that steams and swells as it meets our mouths and lungs. The temperature, the endless bloody sun, is all we talk about now. It is on our lips, our tongues, in our dry throats.

TV meteorologists explain the conditions in terms of air masses and cycles: high pressure is ‘dominating’ and pushing Atlantic fronts carrying rain to the north-west. This, they say, allows temperatures to build elsewhere. The words make it seem as if this is OK, that what we are seeing is part of a normal natural cycle. Nothing to worry about. Nothing to worry about. Nothing to worry about. But, lying here, I can’t get it out of my head that it doesn’t feel right. It doesn’t. The truth of it lurks like a shadow on a hospital scan. There is something wrong. This is the unweder of the Old English, weather that is so extreme it seems to have come from another climate, another world. It makes me realise that not only do I miss the usual contrary weather of Britain, but also that for some time now I’ve been overlooking so much of it.

As a child I used to be fascinated by a weather house that sat on the windowsill at my grandparents’ home. It looked like a thatched cottage, with walls covered in pale pink shells the size of fingernails. It had two doorless openings, both containing a simple model of a person. Under one door, in shaky white paint, was written the word ‘sunny’; under the other, ‘wet’. As if by magic – even when I was told about the interplay between catgut and moisture, it still felt like magic – the sun would draw the smiling man into the open air. Rain, drizzle, an approaching storm, or even a sniff of fog would send him indoors and draw forth the other man from the darkness. He crept forward with his hat pulled down tight as if he were disgusted at the thought of putting a single chipped toe over the threshold.

It is a sentiment that many of us – in many cases, unconsciously – share. The culture of the UK, a place founded on wind-blown migration and the navigation of storm-whipped seas, is undoubtedly weather-soaked. Yet, it seems to me that it is also incredibly lopsided. For the great majority of the population, our livelihoods and day-to-day existence are now long divorced from the practicalities of seed planting or the need for good visibility in Dogger, Fisher, German Bight, and we seem to have forgotten the fundamental importance of those rhythms. Our weather is now too often judged as simply good (sunny) or bad (anything else). The rain, the cold, the wind are things to be endured with chins down and collars up or, if at all possible, avoided altogether.

It’s an easy narrative. The sun boosts feel-good hormones, serotonin levels, and gives us vitamins. The sun is life. It nourishes us, helps us wake, helps us sleep. From an early age, as soon as a fist can hold a yellow crayon, we see the sun as a symbol of happiness. We bathe in it. We worship it. We follow its light. But what if we could find equal joy in other weather? Learn to appreciate the refreshing beauty of the rain; the wild freedom of a whipping wind; the dazzling reflections of light on ice; the otherworldly nature of fog. What if, rather than staying indoors, we could go out and embrace all this so-called unpleasant weather? After all, if the sun has become inclement, glaring down on us without mercy, could other weathers be luminous and nourishing if only we open up to them?

So, this year, I am determined to redress the balance, to look again at what is our most widely accessed experience of the natural world and realise that not only can it be beautiful and sublime, but it can also be fun.

It’s an important point. Many of my childhood memories – some of them now as brittle as old photos – are centred around just being in weather: the first drops of rain from a thunderstorm; pulling a red sled through a snow-smothered woodland so empty it was as if a spell had been cast; a wind that pushed us laughing down a hill and then rocked our caravan so hard I could hear my dad swearing through gritted teeth; a sea fog so thick we could only hear each other’s voices as we ran to the waves. I want to recapture those feelings, to make new memories for my own family – to rediscover the kind of childlike wonder that makes the world suddenly seem so big, new and exciting again.

I resolve not just to brave inclement weather but to actively seek it out and enjoy it: to explore and understand where our weather comes from, the ways it can so dramatically transform the light, textures, shapes and colours of a landscape, and the effect it can have on us – our behaviour, our mood. How it has inspired poets and artists, seeped into our language, and fundamentally shaped our way of life on these isles. How its wildness makes it a rare part of nature over which we have no control. I will revel in the sheer variety of weather that washes over this archipelago, and use it as my lens to observe the world afresh. After all, when our death lies sly in the long grass of unnumbered days, we cannot live our life only in the sunshine of spring. Life needs to be grabbed with both hands. Because to experience weather, to see and feel how its patterns change, is to notice the rhythms of the planet, to see how the different facets of the world interconnect.

I will follow so many that have gone before in taking down the weather in notes and diaries. I will fill my life and home with the elements: rainfall in the bedroom, dew points in the bathroom, hoar frost and the north wind in the kitchen. It won’t be a universal analysis of weather, but rather a personal story of walking, swimming and reflecting on a year of weather. It will be a way of recalibrating myself and reminding myself to take time to notice. Perhaps it may be a useful stepping stone to help others do the same.

So, let the rain pierce the skin like splinters. Let the snow form crystals in your marrow, let the wind circle and rush into your ears until you hear the blown tide of your own blood. Dress for it. Don’t dress for it. Close your eyes to it, open your lips and arms to it. Throw open the doors, windows and soul to the sublime wildness of weather.

RAIN

At times rain is a devastating disruption that explodes into our lives, transforming rivers to destructive torrents and sending floods into our homes and businesses. But mostly it is simply seen as an annoyance; an inconvenience that stops play, ruins weddings, picnics, camping trips, sports days and hairdos. Dull, dreary, miserable days filled with grey cloud, drizzle and mizzle. When was the last time you deliberately went outside to feel the rain on your skin?

By avoiding rain, we’ve forgotten how to appreciate it – how it falls, how it feels, how it affects the land. Our knowledge has been relegated to the wet and wild nomenclature of old: the dabbly rain that sticks to the skin in Suffolk or the moor-gallop of Cumbria and Cornwall where the rain moves in quick-moving sheets across high ground.1

Perhaps it is easy to want to rethink rain now that its absence has stretched on for week after dusty week, but I find myself longing to experience and enjoy it, rather than view it grimly through a window. I want to relearn and relive rain in all its forms: frontal rain that falls when cold and warm air meet; orographic rain caused by air passing over high ground; rain that comes down so hard it takes the breath away. I want to run outside when it explodes out of the blue, to walk through the showers, deluges, downpours and drizzles that leave the world glistening and renewed.

BREAKING. PETRICHOR.STORM. Suffolk, August 2022

In our house we always sleep with the soothing sound of the rain. Google, play the sound of a storm. We ask for it without fail. First, a distant peal of thunder and then a wet tapping that builds quickly to a torrential white noise. My daughter does it too. Every night you’ll find two localised rainstorms rattling around upstairs. Damping down the day, making the house, the bed, feel that much more cosy. We drift off in a safe, rain-ringed harbour. But tonight there is to be a third storm.

We hear it coming in the early hours. The deep, belly-rumble of thunder growing to a vicious crack that sounds like something terrible is being broken. We talk quietly, slipping in and out of sleep, plotting the distance of the storm by counting the seconds between the sheet lightning that flashes white around the edges of the blind, and the corresponding hollow boom of thunder. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten. Divide by five. Two miles. We wait, staring up into the darkness. Flash. I drum the seconds out on my stomach. One, two, three, four, five. Boom. One mile. The air is changing. Becoming charged. Closer, we whisper. It’s definitely getting closer.

We have been waiting for this for weeks. For something, somewhere to shift and for the pressure to be relieved. The storm will be, we hope, the reset switch. A turning off and on again that will make the weather behave in a way that is more, well, normal. That will bring an end to what feels like two months of ceaseless, almost violent heat.

A couple of days ago, on a breathless evening when outside was marginally cooler than in, rain had begun to fall from a lumpy bank of cumulonimbus. Jen and I stood in the garden and looked up until our necks hurt, expecting a downpour, for the rain to turn thick and heavy. The patio slowly darkened, but you could still walk between the drops without getting wet. There was almost enough time for the stone to dry before the next drop fell. This wasn’t yet to be the relief we’d been waiting for.

The smell was there though. You know it. You’d know it anywhere: petrichor.

The word was first used in 1964 by researchers at the Australian CSIRO science agency to describe the yellow-coloured oil, which is responsible for the scent, that was released from rocks after they had been steam distilled. In Greek, petra means ‘stone’, and ichor refers to the golden fluid that flows through the veins of the immortals of Greek mythology. The oil is a combination of plant secretions (signals to halt root growth and seed germination during dry weather) and chemicals released by soil-dwelling bacteria. Some people are said to have a nose for petrichor. So much so they can actually smell when it is going to rain, as the higher humidity causes the pores of rock and soil to fill with moisture and push oils into the air. But the smell is strongest when the rain finally arrives. As raindrops, falling at 9 metres per second (about 20 mph), explode on dusty or clay soil, they trap air bubbles, which are then thrown upwards and out, taking aerosols of scent with them.

For me the odour is sharp, almost animal. It is a smell that bubbles with memories: dust and straw from the rabbit hatch; a single ice-cold drop on the back of my neck; the zing of the rain on the black lid of the barbecue; running down the side of the house to shelter in the garage. It is standing on a concrete floor that is cool to the point of dampness and ringed with oil from someone else’s car while listening to the clatter of heavy rainfall on the half-closed metal door.

There is an excitement with petrichor that I’m sure is linked to anticipation, to relief. We have our personal memories, like mine of the freedom of childhood. But maybe there’s a deeper, older, shared memory too. A memory of a time when our needs were tied more tightly to rain, when it was wished for.

On this evening, the dog seemed to smell it too. Whether it was the rain she was excited by or the change in pressure, she had barked and chased up and down the garden – a skipping, see-sawing sprint, topped and tailed with dramatic pounces and turns that send dead grass and dust flying. She rolled on her back, wriggling her shoulders down into the earth the way she does to collect any scent she deems delicious. Her legs kicked as she rolled before she flipped back over and did another lap of the garden, her ears pressed back against the roundness of her skull. She stopped and stuck out a lolling tongue. A paw raised. Unsure again. I held out a hand. Nothing. The rain had stopped. The drops on the patio dried. The humidity ratcheted slowly back up. Inside the heat hadn’t shifted at all. It stood silent and dark in every room, like a guest who had outstayed their welcome.

The next day I spoke to my parents, who live about a forty-five-minute drive away. Their phone line was crackling the way it does when it gets damp. For years engineers have tested and probed. Dug up the path outside, replaced cables, sucked their teeth and made test calls, but still, when it rains, the phone line crackles and spits. Gobbles up whole words. They had rain, they say, my dad on the phone and my mum shouting from the back. The high street flooded. I know exactly where it will have been. I can see the water pooling at the bottom of the valley down by the line of houses by the Mill, the parade that now houses more betting shops than grocers and bakers, the black timber-framed pub where Lovejoy filmed in one exciting week in the late 1980s.

It used to be the river itself, the Colne, that crept into homes and businesses, but the floodgates stopped that. Now it is the dryness of the land that causes flashes of brown water to rise up to people’s knees. The soil, starved of moisture, has become hydrophobic – it repels rather than absorbs. The water stays on the surface and gathers speed and force as it courses over concrete, brick, paving slab, road and gardens that have been hammered flat by the sun. My dad says he had to turn around by the fire station as he drove into town; the water was too deep for cars. I told him that they stole our rain. The line crackled and fizzed in response. The voices are swallowed.

This night though, the rain will finally arrive in full force. We slept again. We must have done, because when I open my eyes my son is here and so is the storm. Standing in the darkness, he is talking quietly but urgently. His room is at the top of our narrow house. He says it is too noisy, too bright in there. The hair on his legs is standing up on end from the static. The lightning flashes, once, twice, three times and the thunder rolls almost at the same time. Hammer on tin. The anvils of our ears shake. The storm is right above us.

I lift the sheet and Seth gets in, shimmying on over to Jen. The realisation that he’s scared, that he still needs us, still wants us, is as welcome as the rain. He is a teenager now. On the cusp of becoming. He has increasing independence, views, tastes and desires of his own. His life, as it should, is beginning to unfurl from our own. The hand holdings are becoming rarer, the kisses on the cheek are more quickly taken. But tonight he is a child again, his slim back cuddled into my wife’s stomach. His head, with its loose curls, fitting under her chin like it did on that very first night when every part of him felt like something impossible: a wonder, a miracle. I listen to them breathing together. The rhythm of them. The shallow gasp as the lightning flash comes just a heartbeat before the roll of thunder. There is no time for counting now. The storm is right above us, the speed of light cannot outrun the thunder. The rain is so loud it sounds as though water is coming into the house. The gutters have given up. Rain sluices down windows and walls. The building feels like an old wet dog that is done with shaking. I get up and Jen asks what I’m doing. Her voice is soft. Sleep heavy. Cloud thick. ‘Are you going out?’

I am. I hadn’t really thought about it, but I am. I have a strange yearning for the freshness of the rain, the end of this bloody heat. I get dressed, then half undressed again. There doesn’t seem much point in trying to protect myself from the rain when it is hammering down like this. Anyway, I want to feel it. I want to wash the dirt and dryness from my pores.

In the end I step outside wearing nothing but shorts and an old pair of espadrilles whose soles are fraying into yellow bristles. I am soaked almost immediately. The rain takes my breath away. Stings my bare shoulders, which I raise and round as if stepping into cold water. It feels as if the rain is needling through skin and beating onto my bones. I breathe and breathe, taking deep gulps – the air is not scented now, it is clean as a Sunday night hair wash – walking down the path away from my house and turning left to follow the water that is sliding in sheets down the road, bunching up behind car wheels, washing away a month of dust, death, dog dirt and fag ends. The drains take great, gurgling, air-filled gulps, but even more water flows over them, around them. It is about 6 a.m., but a pre-dawn darkness holds, pressed into place by the heaviness of clouds that have locked together to obscure their fibrous edges, their kilometre-high anvil-like tops. Under the streetlights I can see the rain falling in thick bolts, momentarily turning to sparks of light. The ferocity is incredible. Thousands of 20-mph collisions. Thousands of tiny explosions on bare skin.

There is another quick flash of lightning. It reminds me of the man who used to live in the house directly opposite who would play video games into the early hours on a giant projector. I would sometimes wake to see light and shapes flashing silently into our room. Now there is thunder too, juddering from different heights but at the same time directionless, filling up everything with its sounds. It is not a uniform noise like the recordings we listen to at night – that safe, throat-clearing rumble. It is low-flying aeroplanes; it is a heavy suitcase on wheels, dragged over the loose floorboard in an upstairs room; it is standing under a concrete road bridge; it is the roll of bowling ball on polished wood; it is explosive bomb blasts that rattle bones and close your eyes like the snap of a snare drum. They build and ride over each other.

We talk of thunder and lightning, but it should really be lightning and thunder. After all, it is lightning that starts it all – or, if we’re being really accurate, it is ice. In school we are taught that when warm air rises, it cools and condenses to form water vapour. But if the updraught is quick, really quick, the water vapour will form cumulonimbus clouds in under an hour. The warm air will continue to rise inside clouds that at their peak can stretch for 16 kilometres upwards, the water droplets freezing and combining as ice crystals. When the droplets are too heavy to be supported by the updraughts they fall within the cloud, picking up a negative static charge as they rub against smaller, positively charged ice crystals. The negative charge accumulates at the base of the cloud, while the lighter ice crystals gather at the top, forming a positive charge. Like the balloon that sticks to the wall and the ceiling, the negatively charged droplets are attracted to Earth’s surface, to other clouds and objects – including the positively charged ice particles. When the attraction becomes too strong, a discharge of energy is emitted as lightning. The air is heated to 20,000ºC – over three times hotter than the surface of the sun – causing it to expand at such speeds it creates an acoustic wave. A sonic boom. It is the sound of the air snapping back, of energy shaken off, of the weather rebalancing while all the time the rain adds its own endless hiss. I’ve read that, at ground level, a clap of thunder registers at 120 decibels, the point at which sound becomes painful to human ears. It is rock-concert loud, ten times that of the asphalt-biting crunch of a pneumatic drill.

At the end of my road, the lights of one of the bungalows are on. The windows are flung wide, like eyes stuck open, staring onto water that has flashed, gritty and grey over kerbs to fill driveways and lap against red-brick walls. The junction, with its traffic island, its fallen beacon, has been smoothed away to leave an expanse of water that almost reaches to the petrol garage on the main road. I stop and watch the patterns on the surface caused by the falling rain, dimpling and bubbling. I dangle a toe. Submerge a foot. Keep going. Right now, away from the main road, it feels as if I’m walking with the storm. If anything, the rain is getting stronger, beating down so hard it hurts my collarbone and forces my eyes closed. Drops fall, fat and heavy, so hard that they jump back into the air again. It is falling down and up.

But there is something affirming about being in the rain. Something I hadn’t expected. I feel the rain. But somehow the rain also seems to be feeling me. The rain touches every part of you physically. It makes an unthinking map of you, highlights the space that you are taking up. Each drop forces you into some corporeal cogito, to say I am here, I am exactly here at this exact time. This weather, this place, this time. It sharpens the thinking by reducing the world to crystalline pinpoints. It forces you to stop and take notice, to become more aware of your own being, of your movements through the world with its insistent wet touches.

I stop by the main road where cars are now shushing slowly through the floodwater. I stand watching in my shorts until the water reaches my ankles, until the rain begins to ease and gaps open up in the thunder, the lightning sprinting northwards. Then I walk home slowly, feet sloshing, full to the brim with a sensation that feels aerated and sweet as wine. I breathe deliberately, in through the nose and out through the mouth, appreciating the way the combination of early morning and heavy rain makes the day seem clean and fresh. The air is no longer solid, cloying. There is a lightness, a sense of shock, of discharge. The earth has changed, has been restored, by rain. It has made the act of movement, of living, pleasant again.

By the time I’m close to my house, the thunder is distant and the rain has found a more gentle rhythm. The sound of water rushing to drains has softened to the kind of gurgle-drip you would expect in a spring thaw. On a chimney pot, three houses up from mine, a jackdaw is calling. A strange little ‘well, fuck me’ laugh. In the neighbour’s front garden, the sparrows are chattering inside a hedge that offered some shelter from the downpour.

Seth has decamped to the sofa when I get in. Up in the bedroom, Jen is almost back to sleep. She says she enjoyed it well enough where she was, thank you very much.

We talk in low, sleep-beckoning voices about the sound of the storm, about Seth’s reaction, the way he had folded back into us. She remembers how at her primary school there would almost be hysteria as the thunder rumbled overhead. The kids would say it was the clouds knocking together. God moving the furniture. She turns towards me and I wrap my arms around her. I put my hands on her back and ask if I’m cold to the touch. She mumbles, presses her own hand to my chest. Her fingers are splayed, their tips pulsing with heat.

You know it was a hot summer, she says, because I’m so warm. I’m like a Victorian house. It takes a lot to heat my bricks.

I smile in the curtained room, place a foot against a calf. Through the window there is a breeze. The air is sweet, cool and finally moving. The heat has broken.

The rain continues for the rest of the day. The fury, the desperate nature of it left with the storm. It falls instead with an ease, like a long-distance runner hitting their stride. Eating up the miles. A radar map shows a multi-cell thunderstorm made up of a cluster of storms – each probably lasting only twenty minutes – with a squall line of dozens of miles. I set the screen to animation and watch how the column of rain poured north over Sussex, London and then Suffolk. The head of it is a mad scribble of white tracer marks, each representing 300 million volts of lightning.

The national news reports the downpour, picking out the top of the drops. Bury St Edmunds recorded 62.8 millimetres of rain – 2½ inches in old money – in just three hours. The monthly average is 55 millimetres and there is too much for the parched earth to swallow. It fills roads and stands in fields. I think about phoning my parents, to say that this time, this time, it was us who won the rain.

SHOWER. BLANKET. LIGHT.Suffolk, September

The weeks that follow are full of showers. Proper showers, with downpours heavy enough to soak you to the skin in a matter of moments. One arrives as I run a circuit around town, the rain so heavy it makes me gasp, the water forming a film over my eyes that I can barely blink away. It fills my mouth. It soaks into earphones until the music stops and all I can hear is the pump of my own blood and the open-palmed applause of the rain.

The town centre roads and paths aren’t slick with wet; they are submerged. I run with knees held high, guessing where kerbs are, where the slabs dip and rise. The movement of the water is amazing, gushing from all angles; across the cobbles of the car park and the street by the churchyard, tumbling down towards the old Shire Hall and the Court and the police station in inch-thick sheets. It is water that demonstrates the lie of the land in a way that is invisible in the dry. It says this is the shape of things, this is how water and light move.

I used to think that ‘shower’ was a degree of light rain. A step up from a drizzle (with its drops of less than 0.5 millimetres), but several rungs below a deluge. A category apart from ‘pissing it down’. While the nomenclature of rain is varied, there are really only two types: blanket rain and showers. Blanket rain is widespread. It comes from stratus clouds, which are usually part of larger frontal systems that can cover hundreds of miles and can turn entire days the colour of chewed paper. Showers, on the other hand, come from cumulus clouds, formed by convection (the cooling of warm air as it rises), and whether they are cats-and-dogs heavy or spitting light, they are short-lived and localised.

Showers are possible at any time of the year, but they are much more likely during the settled summer months. Throughout the day, the sun heats the ground and the surface air temperature starts to build. The heat is not equally distributed. Darker areas, urban locations, heat up more quickly and when there is a 2- to 3-degree difference air begins to rise. This thermal, this bubble of air, will cool as it rises but will keep moving while it is warmer than the surrounding air. Eventually, the air will condense enough to create shower clouds. Topography is crucial. Showers are especially likely to form over hills where air has been forced to rise and at the coast where cooler air from the sea replaces air that has been heated up on land.

The one that I have found myself running in started quickly, almost out of the blue, as if a tap had been turned on.* But of course, there would have been warning signs if I had only been paying attention, or known what they were. There would have been an increase in the number of clouds, the darkening of their colour. The cloud bottoms would have become ragged. There might have been the dark shreds of pannus, a fractus cloud that forms under a precipitating cloud. The Cloud Appreciation Society describes them as a ‘sort of cloud version of hoodies, killing time outside McDonald’s on a Saturday night’,2 but one that tells you it will rain in five minutes. Maybe there would also have been virga clouds, formed from cloud bases when rain falls but doesn’t reach the ground, their frayed edges trailing earthward like dark, carded wool.

What I do know, is that right now the water, the sheer mass of water, slopping and spouting off concrete and brick, is unbelievable. Past the Abbey Gates the drains bubble into low fountains. Shoppers shelter underneath scaffold boards, using hands and carrier bags to protect their heads from the water that still dribbles through. Others keep walking, moving fast with their shoulders hunched up towards their ears, T-shirts slapped tight to skin.

As a child I would try to dodge the rain with my friends. We would debate techniques, discussing the benefits of going slow, being exposed for longer, against running at full pelt. In 2012, writing in the European Journal of Physics, Professor Franco Bocci suggested that it was a complex issue and the answer depended on an individual’s height-to-breadth ratio as well as wind direction and raindrop size. His advice? ‘The best thing is to run, as fast as you can – not always, but in general.’3