10,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

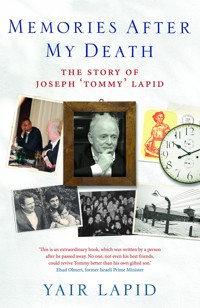

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

Memories After My Death is the story of Tommy Lapid, a well-loved and controversial Israeli figure who saw the development of the country from all angles over its first sixty years. From seeing his father taken away to a concentration camp to arriving in Tel Aviv at the birth of Israel, Tommy Lapid lived every major incident of Jewish life since the 1930s first-hand. This sweeping narrative is mesmerising for anyone with an interest in how Israel became what it is today. Lapid's uniquely unorthodox opinions - he belonged to neither left nor right, was Jewish, but vehemently secular - expose the many contradictions inherent in Israeli life today.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 560

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

Contents

Title page

Endorsements

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Acknowledgements

Index

Copyright

ENDORSEMENTS

Tommy Lapid was my best friend.

It was a miracle that two people who had such a different personal background could find a common emotional language that created a bond of love and deep commitment.

As you'll find out reading Tommy's life story, he was a man with unparalleled devotion to the memories of himself, his family and his people, and an enormous power to emerge with great strength to be a dominant part of building a new and different future.

This is first of all a personal story of one's life – of one person, of one family. But it is also a story of a generation that is disappearing.

This is an extraordinary book, which was written by a person after he passed away, and will continue to be a source of endless pain and hope.

When one reads the story of Tommy Lapid he can't escape the inevitable feeling that the man who is not with us anymore is very much alive and keeps sharing with us all those observations about his life, the world and family that he lost, the family and new life he created and the love for his country which was a source of endless pride and hope that inspired him.

The voice is Tommy's, the spirit is his, but the writing is of Yair. No one, not even his best friends, could revive Tommy better than his own gifted son.

Ehud Olmert

(Ex-Prime Minister of Israel)

CHAPTER 1

I am writing this book after my death. Most people write nothing after they die, but I am not most people.

Or maybe I am. My biography is so full of contradictions that sometimes I used to think – and not only I – that I contain everyone I ever knew. At birth I was named Joseph after a grandfather I never met and Tommy after a Hungarian prince from a long-forgotten dynasty, and I held on to both names throughout my life. I was the most famous atheist in Israel, the public and bitter enemy of Orthodoxy, but I represented (faithfully, I hope) the entirety of Jewish fate. I was despised, but remarkably popular, a polite and educated European intellectual and a red-cheeked defender of the rights of the people whose outbursts were legendary. A conservative chauvinist who knew how to appreciate the figure of a beautiful woman and loved Rembrandt, Mozart and Brecht, and a folksy speaker who could fire up a crowd with pithy one-liners. A leftist who supported partitioning Israel and a rightist whom Prime Minister Menahem Begin chose to run the country’s lone television station. I was an orphan who stepped off the boat with only the clothes on his body, and an affluent member of the upper-middle class who stained his neckties at the best restaurants across Europe.

I entertained SS officers at the train station in the city of my birth, smuggled frozen horsemeat into a cellar in the ghetto, was sent at the age of seventeen to serve in the army of a country I was not familiar with under the command of officers who spoke a language I understood not a word of. In the service of said country, I was invited to the White House, 10 Downing Street, the Élysée Palace, Beijing’s Forbidden City and Rashtrapati Bhavan in New Delhi. I lunched with Barack Obama, drank coffee with Yassir Arafat, raised a glass with Nicolas Sarkozy, marched in Winston Churchill’s funeral procession, toured the Third World with David Ben Gurion, and yet my mother thought I had not amounted to much.

I lived my life with guilt-free passion the way only a person who has been spared certain death can. Long-legged girls shook their shapely bottoms for me from the Lido in Paris to the Mirage in Las Vegas. Louis Armstrong played for me, Ella Fitzgerald and Israeli singer Rita Yahan-Farouz sang for me, I presented an award at the German ‘Oscars’ along with a dead-drunk Jack Nicholson, Danny Kaye was an usher at my wedding, I helped Jackie Mason with his gas mask during a rocket attack on Tel Aviv at the height of the Gulf War. I was an auto mechanic, a lawyer, a journalist, a businessman, a politician and once again a journalist. I wrote successful books of humour and travel guides, my collected essays were bestsellers just like my cookbook, and my comedies were big hits in the national theatre, though everyone – including me – agreed that my wife was a better writer than me.

I disappointed Menahem Begin, I had a complex father-son relationship with Ariel Sharon, I shouted at Ehud Barak, Binyamin Netanyahu claims to this very day that without me he would not have been able to carry out the financial revolution that saved the country, and Ehud Olmert – one of my two best friends in the world – sat at my bedside and watched me die. Watched and bawled.

And I ate endlessly: Hungarian sausages, flaky French baguettes fresh from the boulangerie oven, pungent Dutch cheeses, steaming bowls of hummus with beans in Abu Ghosh, thick beef stews in North America, cream cakes in Vienna, wieners as thick as the arms of whichever Gretchen made them in Berlin, sushi in Japan, chicken tikka in Bombay; once I drank a frightful wine in Burma only to discover, too late, that it had been fermented in pitchers in which monkey foetuses had been placed in order to improve the taste. I ate everything, I ate more than everyone, and I always remained hungry.

But still I need to explain this strange act – by no means the strangest thing I have ever been involved in – that allows a man to write his autobiography after his death. Carlo Goldoni, the eighteenth-century Italian playwright whose most famous work is Servant of Two Masters, once wrote, ‘He only half dies who leaves an image of himself in his sons.’

I am writing now through my son, Yair, but my voice has commandeered his own, just as it did more than once during my lifetime. Is this unfair to him, an injustice? I suppose so. But it is not the first injustice I have committed on him and yet he still loves me in that unswerving and occasionally undiscerning way of children who are willing to accept the image we have created for them.

Without his knowing it, I had been preparing Yair for this moment from the day he was born. I told him the story of my life again and again. As with every good storyteller (and what Hungarian Jew is not a good storyteller?) I studded my stories with anecdotes, ridiculous characters, good guys and bad guys, eternal winners and losers, vistas and flavours and scents, and clever and sometimes cruel observations about human nature and its weaknesses.

And Yair always listened. He was a sad and serious boy, nearly friendless, and I filled the emptiness in his life with exhilaration without ever asking myself whether I was the one who had created that emptiness in the first place. I can picture a scene, toward the end of the 1960s, when we had returned to Israel from London with a new record collection and I sat in my small study in Yad Eliyahu listening to Mozart’s Magic Flute and enthusiastically conducting my battered stereo system with my chubby, white fingers (a part of my body I always hated). It took me a few minutes to notice that he was there, sitting on the floor and imitating me, conducting a piece he had never heard with the fingers of a child. At that moment I suspected – and continued to suspect for years – that that imitation would perpetuate itself and, like many children of successful people, he would become the Sancho Panza of my memories without bothering to develop an identity of his own. I was wrong, of course, but let it be said to my credit that I was happy to be wrong.

Death is a very centring moment. It places before you only the most important matters: parenting, family, love. When I look back on these all I have no regrets. Regret is not circumstantial, it is a character trait, and I admit that it does not exist in me. Time and again I said to my kids, ‘The proof of the cooking is in the pudding.’ If the pudding does not turn out well, no amount of talking about it is going to improve it. And if it does turn out well then the chef deserves an ovation. I had three successful children, and two of them have outlived me. Something was apparently working well in my kitchen.

I did not suffer from a surplus of modesty but I must admit that I would not have bothered to work on this book if my funeral had not been so impressive. It was without doubt a stunning success. The prime minister cried over my grave, many hundreds of people jammed the walkways, the press was there in all its glory, and of course I managed to cause one last scandal by becoming the first person buried in secular fashion in an Orthodox cemetery.

It was cause for celebration in the Orthodox press when word first got out that I was to be buried at Kiryat Shaul. Those are precisely the moments when religion pushes its way into our lives – at the beginning and at the end, when we have no possibility of refusing. Imagine how great their disappointment was when they discovered that instead of a recitation of the traditional Kaddish prayer, Frank Sinatra’s ‘My Way’ would be played. Truth be told, we very nearly failed: just before I was lowered into my grave, Chabad Rabbi Gloiberman appeared on the scene – one of God’s wretched makhers, the kind of fixer I hated my entire life – and started mumbling some incomprehensible verses from the Bible, positioning himself quite naturally in front of the television cameras. Yair put his hand none too gently on Gloiberman’s arm and told him to take a hike. Maybe I shouldn’t have enjoyed it as much as I did in my present state, but I never missed a good fight or a good meal and there’s certainly no point in starting now.

On her way out of the funeral, my wife Shula muttered to Alush (Aliza Olmert, Ehud’s wife),‘I’m so embarrassed.’ Aliza asked her why. ‘I always knew he was important,’ Shula said, ‘but I only just understood how important.’

Don’t be mad at yourself, Shulinka. I didn’t understand either. People asked me time and again to write this autobiography but I always figured they wanted me to write their own biographies and took me for a suitable vessel. There are a few attempts at writing my life story still on my computer but I never got past the first few pages. After all, I was never good at distinguishing what is important from what is not. Everything I ever dealt with seemed, at that time, to be the most important thing. On the Internet site where I played Blitz Chess against opponents from around the world, I racked up 31,731 games, and every one of them, while I was playing, was like a matter of life or death to me. I guess it’s no wonder that I wasn’t able to take life or death themselves too seriously. In a letter I wrote to Barran, a friend from the ghetto, on his seventieth birthday, I noted that ‘in our case, it was a lot tougher to reach our fifteenth birthdays than our seventieth.’

In fact, it was only after my death that I realized – or acknowledged – that I was the last one.

There is nothing remarkable about being the last of one’s kind. In my case it is merely proof that apostasy and stuffed cabbage are a life-lengthening combination. Being the last is not an honor, it is a job. I was the last Holocaust survivor to be a member of the Knesset and serve in the government. After my death there will be no one else to sit on one of those buckskin armchairs who can recall the most horrific event in the history of the world’s nations. I was also the last to remember pre-war Europe, an antique world of crystal chandeliers and women in satin ballgowns leaning gracefully against the shoulders of elegant men. I was the last of Israel’s leaders to watch Churchill orate in Parliament, be present for the creation – and later the fall of – the Iron Curtain, make aliyah to Israel on a rickety boat, listen to the United Nations vote on the establishment of Israel over shortwave radio, serve in the army during the War of Independence in 1948, and to have been on hand, personally, to witness the death of God.

My good friend, the Nobel Laureate Eli Wiesel, once said that memory is his principal occupation. But with me, memory is only a hobby. I was always too busy, too lustful for life, to spend my present on my past. Only now do I understand – with surprise and no small measure of pride – that I was the last in precisely the same things in which I was once first.

CHAPTER 2

Most people do not know at what point they passed from being a child to an adult. I do. It happened one night when I was twelve, between 18 and 19 March 1944.

It was a clear night, the sky studded with stars. My father and I were walking alone down an empty street as I declaimed my Latin: ‘Sum, es, est…’

‘It’s a beautiful night,” I said to escape from Latin.

‘Yes.’

‘Has Mother arrived in Budapest yet?’

She had travelled to be with her sister, Aunt Edith, who had had an operation.

‘Yes. She’s at your grandparents’, showing off your photograph.’ My father smiled.

‘Can I sleep with you tonight?’ I asked.

‘Yes.’

At six in the morning I was still a child. I slept in the huge bed next to my father, under the same blanket. My father was large and fat – even fatter than I grew to be – and his hot breathing was the metronome of sanity and consolation in a world that I already knew, the way a child does, was losing its mind.

This would not be my first brush with the war. It had seared me three years earlier, a few months past my ninth birthday, on April 5 1941, when the Hungarians invaded Yugoslavia. My mother was at that time, too, visiting her parents in Budapest (she would travel there three times a year) and my father and I had packed three suitcases and gone to Belgrade, the Yugoslavian capital, to hide out with relatives. That night Belgrade was bombed. It was the most serious bombing campaign the Germans had engaged in since Rotterdam, and the building in which we were staying was hit by an incendiary bomb. We escaped with our lives. I can recall the way the bombed building shuddered, but even more than that I recall the way each building on that street was aflame like so many giant books of matches. Frightened people ran about the streets, and my father said, ‘Let’s go toward the Danube.’ Burning stones and beams fell from the buildings, and I began to run in a zigzag. My father shouted to me that it would not help because we could not see from where the debris was falling, but I continued running in a zigzag while he – wonderful, conservative Dr Lampel, dignified and deliberate even in such circumstances – continued walking in a straight line, carrying his suitcase. As I ran I heard a noise behind me and looked back. A burning telephone pole had fallen next to me; I had run a zig and it had fallen in the zag.

I was in the habit of telling my Israel-born friends that they had no idea what war was, and this always offended them. What is that supposed to mean? they would protest: Wasn’t the Yom Kippur War a war? And the Gulf War? And how about the Lebanon Wars – first and second? With a bit of arrogance, I would explain to them that real war looks nothing like any of those. In a real war the battles do not take place on the periphery, on the outlying edges. In a real war, 2,500 Israelis could be killed every day, with tens of thousands of wounded civilians and soldiers making their way (or not) to the hospitals. In a real war, ships would be sunk in Haifa Bay, the Defence Ministry in the centre of Tel Aviv would disappear, the government offices in Jerusalem would burn to the ground and cities in the north, centre and south would be razed.

Because that is what a real war is like: no electricity in most of the country; roads blocked with burnt-out cars; trains not running, ports mined, the country is cut off; air force bases wiped out, the Israel Defence Forces fighting admirably even though all contingency plans have been scrapped, the home front hanging on in spite of the fact that during the first week of war we sustained 15,000 fatalities and 100,000 wounded. There is no television, though the radio is still working, requesting blood donations.

My friends fall silent and stare at me. I fall silent and stare at them. I do not tell them one last truth, something I understood on the burning streets of Belgrade, where a man in a suit marched along, determined to maintain his dignity in the eyes of the child running circles around him: in a real war, people who have been saved do not feel any real relief, only guilt. I carried this guilt around with me my entire life. Why my father and not me? Why, from among twenty-four pupils in my class, was I one among only seven to survive? I hope this will not sound too strange, but I even felt doubly guilty because I was actually a good little boy who respected authority and always tried to please everyone. The problem was that everyone wanted me dead. The teachers, the neighbours, the government, the state – all the authorities I had been brought up to respect. Everyone made it clear that death was my job; still, I insisted on living. The war caused me to stop being a good little boy, and I never went back to that. I ran at a zig, not a zag.

In the years that passed I watched – first in anger, later with acceptance – as the Holocaust turned into a literary event (or worse, a cinematic event). ‘Why didn’t you people get out of there?’ I was asked again and again, even by those closest to me. The Holocaust seemed to them like some ongoing event in which people would fade out: first they would lose their jobs, then their property, then the flesh of their bodies, until finally they were loaded onto trains and transported to their imminent deaths. But for Jews like us, the Holocaust was a Mount Vesuvius erupting over a new Pompeii. We were trapped under the lava while preoccupied with the most trivial matters, dying at our desks or making love or walking with our children in the park or drinking our morning coffee and reading the paper without understanding the news was all about us.

Or while sleeping.

One morning, at exactly 6 a.m., I heard Grandmother talking softly. ‘Ja, bitte, bitte,’ she was saying to someone in German, and then the bedroom door opened. ‘Bela,’ she said to my father, ‘a German soldier is at the door and he wishes to see you.’ The soldier did not wait. He followed her into the bedroom dressed in a grey-green uniform and carrying a bayoneted rifle, and was polite as could be. I pushed myself down under the blanket, peering out from beneath it through a slit. I burst out crying. My father rose from the bed and dressed.

‘The rucksack,’ he said to my grandmother. She left the room and returned carrying his bag. There was no need to pack; since the outbreak of war we each had a rucksack prepared for the road.

My grandmother took a step or two toward the blond man with the bayonet and when she reached him, quite close, she grabbed hold of the headboard of the bed and slowly, in the manner of an old person, lowered herself to her knees and pressed up against his polished boots. She raised her head and looked into his blue eyes. ‘Sir,’ she said, ‘please do not forget that you, too, have a mother waiting at home for you.’ Then she added, ‘God bless you.’

The German grimaced, then nodded to my father. Time was up.

Father bent down and took the blanket off me. He hugged me and uttered the words that turned me into an adult. ‘My child,’ he said, ‘either I will see you again in life or I will not.’

I saw him one more time, five years later, but not in life.

It was during my first weekend furlough from the army. My cousin Saadia (his father, Dr Waldman, was a fervent Zionist and called him Saadia without knowing it was a Yemenite name; he was undoubtedly the only blond-haired, blue-eyed Saadia in Israel) brought me to see Tel Aviv, the big city. I was profoundly disappointed. Even in the war-damaged city of Novi Sad that I had left behind, the central square was grander than Tel Aviv’s Mughrabi, and the main street far more impressive than Allenby. When we reached the seashore, Saadia pointed to the Kaete-Dan guest house and informed me with pride that this was Tel Aviv’s largest hotel. I began to understand just exactly where I had landed.

That evening, on the way to the home of Saadia’s parents, we passed a balcony on which young people were dancing the tango. I watched the twirling couples and my heart cinched in a way that only that of a new immigrant can. Mere weeks earlier, I had been just such a young man, a high-school student who had survived the war and danced on balconies with girls I was wooing, surrounded by schoolmates and chattering away in our own language, singing popular songs that meant something to us, eating foods that suited our palates, laughing at the same jokes, looking at the vistas in which we had grown up. And suddenly here I was, amid the alien corn. Homeless. Deaf and mute and hopelessly, desperately, far from ever making anything of myself. When would anyone ever invite me to dance the tango?

That Saturday evening, Saadia took me to the Esther cinema. For the first time in my life I saw a translation from English that was not on the screen itself but next to it, and written by hand. In the intermission a young man carrying a sketch pad approached us. He had heard us speaking Serbian.

‘My name is Lifkovitz,’ he said, introducing himself. ‘I am a painter.”

‘My name’s Lampel,’ I told him.

A flash of recognition lit up his eyes. ‘Are you related to Dr Bela Lampel?’ he asked.

‘I’m his son,’ I said.

‘We were in Auschwitz together,’ he said just as the second half of the film began.

After the movie we sat on a bench in Dizengoff Square. Lifkovitz opened his sketch pad, pulled a thick pencil from his pocket, and said, ‘I’ll draw your father for you.’ I sat beside him on my first Tel Aviv evening and watched with great excitement as the lines spread across the page. When he finished, he said, ‘Does it resemble him?’

‘The contours of his face do,’ I said, ‘but he was fat.’

Lifkovitz’s face fell. He closed the sketch pad. ‘When I knew him,’ he said, ‘he was already thin.’

I cannot imagine my father thin. I do not wish to. I prefer to retain my memories as they are.

CHAPTER 3

On the wall of my study, in a thick frame, hangs an eighty-year-old photograph of the Lampel family. After my death my wife, Shula, decided to leave it there as a memento of a vanished world, and a vanished husband.

Pictured in the photograph are my grandfather, Joseph Lampel, who died a year before I was born and for whom I was named; my grandmother, Hermina; my father; and his two younger brothers, Pali and Latzi.

I do not know how this photograph survived. It was snapped in 1928 at Foto Vaida in Novi Sad, the town in which I was born. The subjects are staged and formal, like some Dutch painting from the seventeenth century: my grandparents, starched and prim, sit beside a small table on which a large clock has been placed and set to the hour of six. My father and grandfather are wearing neckties; the two younger boys wear bowties. No one is smiling.

I grew up in what is known as the Old World. It was a world of luxuriant tranquillity, of honourable, heavy sloth, a world of marble palaces and stone bridges, of long afternoon naps and even longer evening meals, of brass phonographs and pure silver cufflinks, of patient horses and puffing steam engines that run late because tardiness is no crime.

Only a few years later the palaces were blown up and the bridges crumbled. Grandmother Hermina was killed at Auschwitz along with ten other family members. My father died at the Mauthausen work camp only two weeks before the end of the war. Our smiling neighbours turned us in to the authorities, then set their coarse feet in our house and carried off the gramophone, the cufflinks. The trains were derailed, the carriages left to lie on their sides like dice in a crazed giant’s game. We ate the horses. During the daytime we could hear their screams after Russian bombardments and at night we stole from our cellar hideaways in the ghetto armed with makeshift knives and sliced away at their frozen flesh. I am not the kind of person who remembers his dreams, but the sound of those screaming horses stayed with me for long nights over many years.

Sometimes I look at Yair and Meirav and envy them. I envy them, and worry for them. They believe – wrongly – that the world in which they live is unassailable. Their careers, their beautiful children, the things that surround them – homes, cars, bank accounts – give them the illusion that what was is also what will be and that no one can come along and take their lives away in one fell swoop. But I know just how fragile reality is. The world in which I grew up seemed far more stable and permanent than the feverish modern world. It had moved along at a sleepily slow pace for centuries and then suddenly – in a day – the ice shattered and all the dancers plunged into the murky waters.

But it is best to begin at the beginning.

Novi Sad sits on the Danube River, some 80 kilometres north of Belgrade and 220 kilometres south of Budapest. For most of its history it was a border town that looked after the south-east corner of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The first Jew in Novi Sad, a man named Kaldai, arrived in the seventeenth century. One hundred years later, in 1749, the town had 4,620 inhabitants, of which 100 were Jews. By 1843, some 1,125 Jews were registered in Novi Sad, among them several doctors and the ‘fat Jewess Pepi’, the pushy madam of the Golden Girls brothel. According to documentation, in 1836 she was fined when soldiers who visited her establishment contracted a venereal disease.

There were 80,000 residents of Novi Sad prior to the outbreak of World War Two, including 4,350 Jews. We were three of them: my father, Bela; my mother, Katalina; and me.

They seemed like a perfect couple. He was known as Bela the Bright and she as Kato the Beautiful. He was a dark-eyed, dark-skinned journalist and lawyer from the outskirts and she was a gorgeous blonde from Budapest, the metropolis, never letting anyone forget that we were, in her eyes, rustics. They met when she came to visit relatives of ours, the Korody family, a large suitcase filled with the latest fashions in tow.

In no time she grew bored – there was not much to do in a family whose favorite way of spending time was to paint on eggs – and persuaded the two younger daughters, Vera and Mira, to bring her to the community center for evenings of dancing. It was there that my parents met and fell in love. He was relatively old by then, and the fact that his two younger brothers had already married caused the family to spare no effort in matching him up with a girl from the local Jewish community. He refused them all, until my mother came on the scene: she was tempestuous, flirtatious, frivolous and without doubt exceptionally beautiful. Small cities are naturally suspicious, and eyebrows were raised. My mother came from a family of relatively meagre circumstances and the rumour that circulated (thanks to the disappointed mothers of the city’s unmarried Jewish girls) was that she was interested in him solely for his money.

On 5 July 1930, my father took a holiday at the Grand Imperial Hotel in the Dalmatia region of Croatia. Appropriately named, the Grand Imperial was an imposing building with ornate Corinthian pillars set on an enchanting strip of sand on the Adriatic coast. (In the 1980s, the building was razed and replaced by an ugly modern hotel that bears the same name.) It was there that my father sat and wrote – in neat, compact handwriting that concealed the tremendous storm of emotions he was experiencing – a letter to his father:

I am thirty-two years old and I long for the tranquillity of married life. My great loneliness is slowly grinding away at my nerves – I cannot find my place – I can no longer stand it. Sometimes it angers me that you and Mother did not appreciate my endless wandering, my constant malaise, my attacks of nerves which repeated themselves with growing frequency. And now you know the reason. It was my terrible loneliness that caused it… Throughout my life I have only been capable of glimpsing happiness from the side, which caused me to be increasingly bitter as I looked around. But now, as the decision to marry Kato has ripened in me (if in fact she will have me), I feel, for the first time in my life, what it is to be happy.

Father, this is what I wished to tell you, and I can only add what Luther said: ‘Here I stand, I can do no other.’

I embrace you and Mother,

Bela

I read that letter again and again during my lifetime trying to see the connection between the staid man I knew and the melodrama unfolding with his words. Perhaps it is decreed that we shall never know the truth about our parents, but it seems to me that this was a moment of loneliness of operatic proportions that occurred in a life that was otherwise remarkably calm and ordered. As far as I could tell, the power of the connection between them was that it suited them both. My father gave her the easy life she desired and he in return received the most beautiful flower in the city to put on his lapel. Is that love? Does anyone know what love is?

Our villa was three storeys tall and capacious and faced Train Street. Rose bushes and pear trees bloomed in the large back garden. Father’s law office occupied the ground floor, along with the servants’ quarters. My parents’ bedroom, my bedroom, my nanny’s bedroom and a guest bedroom (which usually stood empty) occupied the top floor, while on the first floor there was a large living room, a separate dining room, and another spacious room called ‘the master’s room’, which was elegantly decorated with heavy furniture that included an escritoire, a well-appointed library and a large armchair in which Father took his naps. Naturally, there was also a large kitchen presided over by our fat Hungarian cook who toiled over a gas oven, since the Novi Sad gas company had already by that time installed pipes through the entire city. (When I first came to Israel and discovered that gas was distributed in canisters, I understood I had arrived in a primitive country.) A dumb waiter operated from the kitchen to the roof terrace, in case we wished to dine up there.

Today it seems to me that only very rich people live in such a manner, but back then this was the norm for the bourgeoisie, who saw themselves – correctly – as the cornerstones of the entire society. It was a comfortable milieu of masters and servants, and no one gave too much thought to his or her status. The cook and the maid, who lived with us, were Hungarian. The gardener, who came once a week, was Serbian. Lizzy, my nanny, was a Swabian German. To my dying day I found it hard to polish my own shoes, and not just because of my extra poundage, but because in my childhood it was abundantly clear that this was a job for the servants.

But perhaps the most notable feature of status was not the size of one’s house or the number of servants but the comfortable pace of life.

Father would rise at eight, read the newspaper, and eat a leisurely breakfast until Mother would remind him – from her bed, with the aid of a small bell – that he needed to be in court at ten o’clock. At nine he would descend to his office where his two legal interns awaited him with documents. He sat importantly at his desk while one of his two secretaries served him coffee in a Rosenthal china cup. From there he walked to court, after which he would spend time at the nearby café, where he would have a bite to eat, browse the weeklies hanging from bamboo poles and return home in a carriage.

After we ate lunch, he would retire to his armchair in the master’s room and sleep for a quarter of an hour. From there he returned to his office, met with clients, perused documents, and dictated letters until six o’clock, at which time he would climb the stairs to our living quarters, listen to the radio, read a book or go out for dinner and then a game of bridge. Once a week he would travel one hundred kilometres to the city of Sobotica, where he would remain overnight in order to edit the weekend supplement of a Hungarian daily called Unpel, owned by a rich Jewish family. One evening a week he would devote to writing an article, usually by hand, which he would then type on his Remington. His opinions, which were the kind espoused by Jews of his type, were moderately liberal. On the day I was born – 27 December 1931 – he wrote a piece praising Mahatma Gandhi and his struggle against British imperialism.

The metronome of his life ticked at an astonishingly slow pace. He would speak on the telephone only two or three times a day; he listened to the news at ten in the evening; he had time to explain things to me and to listen to what I had to tell him. As an only child I had no competition. On Sundays he would take me to watch the Vojvodina football club play. To this very day I can feel my small hand in his large, warm hand as we walked into the stadium.

I wonder sometimes: to where did all that time that stood at my father’s disposal disappear? How was it possible to maintain such a slow pace, no televisions or computers or mobile phones or cars? Perhaps it is because all those appliances, designed to save time, did not eat away at his time?

And yet, my father’s pace seems like a typhoon compared with that of my mother’s. My nanny, Lizzy, would wake me up each morning, bathe me, prepare my breakfast, dress me and bring me to my parents’ bedroom, where Mother was still in bed. We could not embrace because she was smeared with creams designed to prevent wrinkling, so she merely eyed me from afar, blew me an air kiss and sent me on my way to kindergarten or school.

Only after Father went to his office did my mother emerge from her bed. She would take a short walk around the house, checking to make sure the maid had done the cleaning and polishing. This was the extent of her daily labours. For what remained of the morning she would chat on the phone with friends, go shopping, or meet a girlfriend for coffee at the Dornstadter café in town.

Lunch was served by the white-aproned maid at the heavy mahogany table in the dining room. Throughout the meal I had to make sure my elbows were kept firmly at my sides and never on the table itself, heaven forfend. If I forgot for even a moment, my nanny would be asked to bring two books that I would be required to place under my arms, one to a side, and eat without dropping them to the floor.

After lunch, Mother would simply be exhausted. She napped for two hours in order to awaken refreshed for the bridge game she looked forward to in the afternoon, either at our house or at the home of one of her friends. If she and Father were invited out in the evening, she would stay home and read in the garden or on the roof terrace. This was when she would play with me. She quickly discovered that I had no talent for musical instruments or singing or drawing, a fact she found singularly depressing since she wholeheartedly believed that the highest purpose in life was that of beauty. As compensation for my dearth of talents, she bought me a card game called Quartet, the object of which was to collect four paintings each by famous artists. That was how I learned, at age seven, that there was a Spanish artist named Bartolomé Esteban Murillo who had painted ‘The Little Fruit Seller’, ‘The Young Beggar’, ‘Two Children Playing Dice’, and ‘Beggar Boys Eating Grapes and Melon’ in which the grape-eating boy held a bunch of grapes over his head and slipped them into his mouth much as Greta Garbo did in Queen Christina.

It is not by chance that my favourite painting was of children eating. Years later, when I had already earned a reputation as an insatiable glutton, I pretended to be making up for what I had lost in the ghetto. That may have shut people up, but there is not an element of truth to it. I was always a big eater, from as early as I can recall. Not only me, but everyone in my life. Today, the papers are full of cooking columns and restaurant reviews but all that is nothing compared to the monumental role that eating played in our lives.

The lion’s share of my childhood memories is connected to food: talking about food, secret recipes, arguments about whose cook was the best, visions of a pantry in which Pick and Herz sausages swung lazily, and behind them stood colourful bottles of winter preserves: plum, strawberry and apricot jams; cherry, pear and peach compotes; cucumbers pickled in vinegar and cucumbers pickled in brine – rows upon rows of tempting jars waiting their day.

Each morning, Mother would speak with the cook about the day’s menu. It was a deep and lengthy discussion in which the courses would be selected according to the season. Calories were not a consideration, even though on occasion Mother would force Father to diet. At such times, Father would sneak off after appearing in court to Café Sloboda for a little dish of chicken livers with paprika. If school let out early he would have me join him, and for me he would order a pair of sausages with horseradish, on the condition that I not tell Mother, of course. Each summer, during the court’s recess, Father would spend two weeks at the Carlsbad spa in Czechoslovakia, where he would shed ten kilos that he would quickly regain at home.

My two uncles – partners in a mirror manufacturing factory – and my father, the elder brother, would often go hunting together, and on occasion I was invited to join them. We would rise at five in the morning on a Sunday and travel a few dozen kilometres to the area surrounding the village of Kać, where there were ample hunting fields. (The pride of the townspeople of Kać is native son Milos Marić, a Serbian officer born in 1846. Marić’s daughter Mileva was one of the first women to study mathematics and physics in Europe and was Albert Einstein’s fellow student and, later, his first wife.)

The youngest of the Lampel brothers, Latzi, was the most serious of the three hunters. Stag horns adorned the walls of the hunting room in his villa and the sofa was covered in the skin of a bear he had hunted in the Carpathian Mountains. Uncle Latzi had a hunting dog he prized, a pedigree pointer named Lord who went about with his head held high and his tail erect, as befitting an aristocrat. Once, on a morning we were supposed to hunt, Uncle Latzi was ill. After much argumentation he was persuaded to let my father and Uncle Pali take the dog with them. We went out to the field, where Lord uncovered a flock of pheasants that he dispersed. My father and Uncle Pali fired but no bird lost even a single feather. We trailed along behind Lord, who sniffed this way and that, until once again he pounced on a flock of birds hiding in the underbrush. Once again the birds took flight and once again the amateur hunters failed to down even one of them. Lord gave us a scornful look, turned on his heels and headed home.

I am not only recording here the biography of the life I lived, I am also recording the life I missed. My father wished for me to be like him and I wanted the same. In some ways, I have even succeeded: it is not by chance that, like him, I became a lawyer and a journalist. The difference is that I did so in a different country, as a different person. Sometimes I wonder what would have happened if a single year – March 1944 to June 1945, the sixteen-month period that constituted the Hungarian and Serbian Holocaust – were removed from history. Would I have lived in the villa next to my parents, maybe even in the very same one, after inheriting my father’s thriving practice? Would I have married a beauty by the name of Ruzy and napped in the master’s room each afternoon facing his portrait? Would I have spent evenings writing nostalgic articles about the late Mahatma Gandhi for Magyar Hírlap, the largest Hungarian newspaper?

CHAPTER 4

‘Iyou don’t believe in God,’ some angry ultra-Orthodox politico shouted at me during one of the Popolitika television programmes, ‘then who defined you as a Jew?’

‘Hitler,’ I shouted back at him.

For once there was silence in the studio.

God was not a major preoccupation for me during my childhood, and after the Holocaust I stopped believing in Him altogether (in my present situation I am in possession of information that I am sorry I did not have access to during my lifetime; it could have done wonders for my political career). But all this does not mean that I am not a Jew. In fact, I am a Jew in the deepest way possible. Judaism is my family, my civilization, my culture and my history. The people who insist on holding inquisitorial investigations in order to classify me as a first-class or second-class Jew amuse me. There is something ridiculous about the idea that faith in God turns Judaism into a rational matter. After all, the very act of believing in God is irrational, which is why it is called ‘faith’. Thus, in the very same measure and with no less conviction, I believe in my Judaism with all my heart and soul. To paraphrase Shylock’s famous speech in The Merchant of Venice, I am a Jew because I have eyes, I am a Jew because I have hands, sense, affection and love; if tickled, I laugh like a Jew, if stabbed I bleed like a Jew, if poisoned I die like a Jew.

Two popular rumours swirled around my heresy, and both were imprecise. The first was that, like most European Jewry, I was a believing Jew but lost my belief in God in the ghetto. The second was that I was raised in a completely secular household in which pigs were slaughtered every winter (that’s true) and that I had never heard a prayer service in my life (that’s not).

I suspect that the former chief rabbi of Israel, my friend Rabbi Israel Lau, is the source of the first rumour. We were the two most famous Holocaust survivors in Israel and we argued a lot. He never grew tired of trying to persuade me to ‘return’ to Judaism, and I never grew tired of explaining to him that I had nowhere to return to. After my death he published an article in which he described our final meeting, when I lay on my hospital deathbed, in which he wrote, ‘With regard to his attitude towards religion and religious people, it seems that Tommy has undergone some sort of transformation.” As my doctors and family members can attest, this foolish statement has no grounding in reality, and if I were still alive I would settle accounts with him.

The source of the second rumour is one of the more embarrassing moments of my life. It happened some two weeks after I arrived in Israel as a boy of seventeen sent straight from the boat to basic training. Those were confusing times for me, and I had trouble sleeping at night, or, in the words of the great Hungarian humourist Frigyes Karinthy, ‘I dreamt I was two cats fighting with each other.’ One morning I awakened at dawn and stepped outside the tent to relieve myself. On the outskirts of the camp I caught sight of a man wearing a square transmitter on his forehead and an antenna which was attached to his forearm; he was rapidly muttering his report to the enemy. I raced to my commanding officer and informed him I had caught an enemy spy. The officer burst out laughing. ‘You mean to tell me,’ he said, ‘that you’ve never seen a Jew don tefilin for the morning prayers?’

No, in fact I had not. But that still does not mean we knew nothing about Judaism. Judaism played a meaningful role in our lives, even if it was carried out in the same relaxed manner that we did everything else.

The Jewish community of Novi Sad belonged to the Neolog stream of Judaism, a mild reform movement within Judaism, practised mainly in Hungarian-speaking regions of Europe, which began in the late nineteenth century and would today fall somewhere between the Reform and Conservative movements. We had a large and beautiful synagogue, one of the loveliest to be found in central Europe, with an enormous organ behind which sang the choir. Men and women sat separately and the men covered their heads and wore prayer shawls. We could read Hebrew letters and chanted the prayers in that language, but without understanding a word of it. The rabbi gave his sermons in Serbian (the official language) but in the aisles of the synagogue and in the women’s section, juicy gossip was spread in Hungarian. In fact, we all knew three languages equally well: Serbian, Hungarian, and German, which was the preferred international language in our part of the world. We attended synagogue three times a year: on Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur and Passover.

Had our activity ended there it could have been claimed that ours was a feeble form of Judaism, but in fact it did not. Our synagogue was situated on a large piece of property on one of the main thoroughfares of the city. At the far end of the property stood the three-storey Jewish community building that boasted a banquet hall, a cafeteria for Jewish students who came from the surrounding villages to study in Novi Sad, and an archive of documentation pertaining to the city’s Jewish history. (The archive remains intact; it enabled Yair to find the communal grave of our family where he went to pay his respects, up to his knees in snow.)

Behind the synagogue stood the building of the Maccabi sports organization, with a large, well-appointed gymnasium where I worked out twice a week. There were rooms for the different Maccabi sporting groups: football, handball and even henza, a kind of handball for women that has since disappeared from the world of sport. There was a chess and checkers room that was mostly used for card-playing. On the top floor the youth movements had offices, everything from the left-wing Shomer HaTzair to right-wing Beitar (I was in the Scouts). There was even a spacious theatre used mostly for concerts. My Aunt Ila – Latzi’s wife – was a pianist who appeared there often, and the entire family would attend her performances.

But I have not mentioned the most important thing of all: the Jewish school, where I studied for nearly four years (elementary school in Yugoslavia lasted four years). The teachers’ salaries were paid for by the community, and both the level of instruction and the well-equipped classrooms were of a standard higher than that of the public schools. Thus, the Christian elite of Novi Sad also sent their children to the Jewish day school. In our Judaism classes we learned the Hebrew alphabet, and I can still mumble the Shma Yisrael prayer without error, but with a strange accent. We learned the Bible stories and Jewish history in Serbian.

All of this created a very Jewish atmosphere, if not a particularly religious one. At our house we celebrated Hanukkah; at my grandmother’s house there was a pushke for collecting money for the Jewish National Fund, and on the wall a print of Abel Pan’s The Shepherd. Grandmother was the president of the local WIZO chapter; Father was, in his youth, secretary of the Zionist Federation and, later, president of Bnai Brith; and Uncle Pali was head of the Novi Sad Jewish community after the war. None of this required lighting candles on the Sabbath, or donning a prayer shawl or a pair of tefilin. The most religious thing that took place in my life, apart from my circumcision, was when Grandmother’s brother, Uncle Sándor, swung a chicken over his head as part of the preparations for the Yom Kippur holiday of atonement. And that was funny, and not very convincing.

The two customs we did keep were the lighting of the candles at Hanukkah and the Seder meal at Passover. For that holiday, my father had a leather-bound Haggadah. Starting in 1931, he listed the participants at our Seder meal each year on the blank pages found at the beginning of the Haggadah.

Unlike my father himself, my father’s Haggadah survived the Holocaust. After the Jews of Novi Sad were expelled, our Hungarian neighbours looted our property and made off with furniture, household utensils, paintings, clothing. Everything. Whatever was left behind was stored by the authorities in the city’s large synagogue. Upon our return from the concentration camps and ghettos, we were sent to the synagogue to look for our belongings. I can still recall the scene: dozens of Jews, pale and thin, scrounging among the shattered furnishings, the faded piles of clothing, and the broken utensils that remained behind after the non-Jews had picked them clean and taken anything that appeared to have value. There were also quite a large number of books; among them, Uncle Pali was amazingly lucky to find the family Haggadah. Three years later he added to it the three most important words in the history of our family: Moved to Israel.

CHAPTER 5

Throughout my life I was blessed – or cursed – with an exceptionally good memory. I can recall flavours, scents, books that I read, people I met and conversations in which I took part. Even after Google came on the scene, my eldest grandson, Yoav, an insatiable trivia addict just like me, continued to phone with questions like where the first May Day was commemorated (at a rally in Chicago) or which monks wear brown cloaks (Franciscans). I would answer and he would thank me and ring off before I could ask why the hell a staff sergeant in the Israeli army would need such trivial information. It is only with respect to myself that my memory is hesitant. I know that Uncle Latzi was assertive and Aunt Ila was fragile, but what kind of child was I? Philip Roth, one of my favourite authors, once wrote, ‘Memories of the past are not memories of facts, but memories of your imaginings of the facts.’

My earliest true childhood memory was also my first trauma. One day, when I was about five years old, a farmer brought my father a lamb as payment for drawing up a contract for him. My father gave it to me as a gift for me to play with in the garden. I named him Mickey. I fed him milk and lettuce leaves, I played with him. This lasted for several weeks, during which time Mickey grew and the connection between us deepened. Then one day he disappeared. I looked all over for him; I cried, but Mickey was nowhere to be found. That evening at dinner, during the main course, I complained bitterly to my parents about Mickey’s disappearance. My parents exchanged glances, and suddenly I understood that we were eating him. I jumped up from the table, ran to the bathroom and heaved the contents of my stomach into the toilet.

It could be that this was not an exceptional tale in a provincial town surrounded by villages, but at least it hints at the fact that I had protective parents who tried to spare me the difficulties of life. (Years later I ate a wonderful lamb roast with Ariel Sharon at his farm; the fearless warrior admitted that the meat was purchased from a butcher because he could not stomach eating an animal that had been raised on his farm.) My parents never raised a hand to me, I was permitted to speak during meals as much as I pleased though this was unacceptable in those conservative times, and I do not recall asking for something that I did not later receive. I was a spoiled only child, and to this day I believe that pampering a child does no damage as long as it is not a substitute for love. When I was forced to be resilient, which happened to be at a very young age, I proved to possess rather remarkable survival skills.

Father was the centre of my world. I had many friends, but a patient father, one who was always willing to set aside time for me, was a true asset in those days. He could be very assertive when necessary, but he always had time to sit with me, to take me to a football match, to check my homework, to read the newspaper with me and to explain where Bosnia-Herzegovina was located, or who the Pharaohs were. At night we would raid the kitchen together, where he would make himself a Körözött (soft white cheese with anchovy spread, paprika and chopped onion), all the while describing for me with wildly gesticulating hands the heroic victory of Ilona Elek, the Jewish fencing champion of Hungary who took the gold medal at the Berlin Olympics right under Hitler’s disappointed nose. (It is interesting to note that Elek’s opponent in the finals was Germany’s Helene Mayer, one of only two Jews permitted to compete for Germany in those Olympics.)

* * *

I was able to read from the age of four and I did so incessantly. I read Pinocchio, The Baron Munchausen, Der Struwwelpeter, Max and Moritz, Peter Pan, Edmondo De Amicis’ Heart, Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans, and, to this very day I cannot forget how I cried when Little Nemecsek died at the end of Ferenc Molnár’s The Paul Street Boys. However, my favourite book of all was Old Shatterhand. At the time I had no way of knowing that its author, Karl May, was a crook who had never set foot in the Wild West he described. Many years later, when I was a politician, each time I wished to end an argument I would bang on the table and say, ‘I have spoken!’ which made a great impression of authority on everyone in the room. What no one knew was that I was simply quoting Winnetou, the book’s Indian hero.

When I had finished reading all the children’s books I could get my hands on, my father permitted me to browse his private library, where I encountered Edgar Wallace’s spy novels, all bound in blue and first featuring that clever investigator J.G. Reeder and later stern Sergeant/Inspector Elk. I was smitten. Wallace is a nearly forgotten writer today, but he was a talented and productive author who wrote one hundred and seventy-five novels, twenty-four plays and hundreds of articles in various newspapers. At one stage, one-fourth of all the books sold in the United Kingdom had been written by him.

This great investment in reading apparently paid off, since within days of starting school it was clear to me that schoolwork came easier to me than to the other children. Happily, that did not cause them to bear a grudge against me. It turned out that everyone expected the son of Bela the Bright not to be stupid. Although I was not particularly good at athletics, I became one of the class leaders. Physically, I was medium-sized for a Jew but was always looking up to my Serbian classmates. (The Serbo-Croatians are among the taller peoples of the world; it is no wonder that this small region has produced many noted basketball players.)