Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

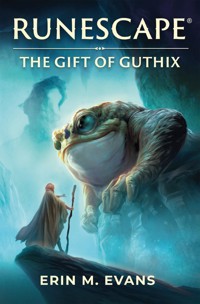

A thrilling epic of betrayal and magic set during the founding of Falador and the doomed Fremennik Great Invasion. Sure to delight RuneScape fans old and new, this stunning tale shows how the gift of magic changed the course of Gielinor forever. Asgarnia's fate hangs in the balance. Disparate tribes unite under the banner of Lord Raddalin, and his enemies look on in fear and hatred. Raddalin's advisors – an uneasy alliance of Black and White knights – whisper of a discovery in the North that will give them the power to change everything. Caught in the midst of history, a lowly scribe and the son of a Jarl hold the fate of Raddalin's new kingdom in their hands. From the glorious inauguration of King Raddalin's reign to the disgraceful expulsion of the Zamorakians from Asgarnia, The Gift of Guthix tells an epic tale of the origin of magic, the plight of civil war, and the crushing defeat of the Fremennik Great Invasion. Amongst plots and betrayals, a penitent turncoat waits for her moment to leap into the unknown.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 494

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Part I: The Founding

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Part II: The War

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Part III: The Tower

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven

Twenty-Eight

Twenty-Nine

Thirty

Thirty-One

Thirty-Two

Thirty-Three

Thirty-Four

Acknowledgments

About the Author

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Runescape: The Fall of Hallowvale

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

RUNESCAPE: THE GIFT OF GUTHIX

Print edition ISBN: 9781803365213

Electronic edition ISBN: 9781803369235

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: May 2024

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, places and incidents are either products of the authors’ imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2024 Jagex Ltd.

Published by Titan Books under licence from Jagex Ltd. © Jagex Ltd. JAGEX®, the “X” logo, RuneScape®, Old School RuneScape® and Guthix are registered and/or unregistered trade marks of Jagex Ltd in the United Kingdom, European Union, United States and other countries.

Cover illustration: Mark Montague and Terence Abbott.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To all the ones who never stop.

PART I

THE FOUNDING

I should have seen this as a sign of things to come, but I hoped that in free rein they might see the harmful impact for themselves, and gain enlightenment from their destructive impulses.

—THE WORDS OF GUTHIX

ONE

THE SEVENTH YEAR OF THE REIGN OF LORD RADDALLIN OF THE DONBLAS TRIBE

THE SEVENTH DAY OF THE MONTH OF SEPTOBER

FREMENNIK PROVINCE

Ilme came to the shore of the Wolf Clan’s summer encampment on a cold tide, two lies in her mouth and a gifted green cloak wrapped around her shoulders.

Master Endel regarded her with a scrutiny so thorough that panic curled in Ilme’s stomach—he had surely figured her out. But he only refastened the silver brooch, shaped like a crescent moon, to sit higher on her shoulder and brushed something off the fabric there. He gestured at her long brown braid.

“Do something about your hair,” he said, almost pleading. “Look less… guileless. We’re aiming for ‘aloof’. For… ‘youthful wisdom’.”

Ilme undid the plait and cast a sideways glance at Endel’s apprentice, Azris, her dark hair piled in a knot of loops at the crown of her head. Ilme thought of Endel’s second apprentice, a girl called Eritona, her rows of braids sleek against her elegant head.

Eritona was not here as she had fallen ill and remained behind—but everyone knew the Moon Clan travelled in groups of three and no one would accept them as mages from the Lunar Isle if they didn’t. So Master Endel had needed a replacement and Ilme, guileless and unwise, would have to suit.

She raked her fingers through her brown hair and felt worry twist her stomach again. Eritona had fallen ill at the very time Ilme needed to go north. Someone might have poisoned her. Someone might have made certain Ilme was the one who followed Master Endel north, and if that came out—

“Fortunately,” Master Endel said, as the ship swayed beneath them, “my understanding of the Fremennik suggests that the jarl will leave you be. They don’t value youth and he will assume your magical aptitude makes you untrustworthy.”

Azris cast a sceptical glance at Ilme. “Master, won’t that mean he’ll assume you’re untrustworthy?”

Master Endel waved this away. “I don’t intend to become the jarl’s confidante—only to solve a mutual problem.”

“I still don’t understand how having a rune cache is a problem.”

“Because you are not Fremennik. And you are not of the Moon Clan, but since here you are supposed to be an initiate of the Moon Clan—” here he gestured to himself, to his own borrowed green robes, “—you should just accept that it’s the case.”

This was the first lie: they were not from the Moon Clan, far up across the Northern Sea, where those mages hid themselves. The Moon Clan didn’t believe in runes. Rune magic was what had caused all the world’s problems before—putting magic in the hands of anyone who could grasp it, regardless of their worth. If you were pure-minded and dedicated, then magic would come to you just as it did for the Moon Clan. Magic they did not teach to outsiders. Not willingly anyway.

But the Fremennik were the Moon Clan’s warrior cousins, in a way, and when there was a question of magic, the Moon Clan were the ones they would naturally reach out to—not the upstart court of a warlord of the south. So when Master Endel heard the rumours of rune essence found in the far north, this had been the plan he’d settled on.

“Are there male mages among the Moon Clan?” Ilme asked, trying to twist her hair up like Azris’s. “I heard they’re all women.”

“I heard they’re all demon-worshippers,” Azris chimed in.

Master Endel sighed. He was a small man, narrow-shouldered and trim-bearded, but what he lacked in physical presence he made up for in wit and wisdom. “Azris, if you are going to become a wizard, you are going to have to be less credulous. The Moon Clan are not demon-worshippers. They are Guthixians. More or less,” he added.

Master Endel, like most of the wizards Ilme had met including Azris, knew the names of spells and their methods of casting, the lore of the days before the God Wars shattered everything humanity knew. Like some, he had access to the stores of ancient runes, cached or collected, from which powerful magics could be formed.

But in his youth Endel had travelled to the Lunar Isle, the solitary refuge of the Moon Clan mages. He had slipped past the Moon Clan’s guards, and had gone down into their sacred rune essence mine—too holy to touch—and come out with rune essence and a scar in his ribs. He found a way to shape that essence into runes—daring strange and ephemeral plumes of elemental power to force them into shape—and travelled far and wide to scrape together more remnants of essence.

But no one, not even the fabled mages of the Moon Clan, were like the wizards of old, shaping runes of power and combining the gleaming stones into spells at a whim. The last time Endel had done anything extraordinary had been a terrific burst of flame that he’d spent a fistful of fire runes to create, which had sealed the Donblas Tribe’s success against the Caracalli in the earliest days of their campaign. Ilme had been eight when that had happened.

“The Fremennik as a rule do not work magic,” Master Endel said, as the sailors started loading things into the boat meant to ferry them to shore. “They don’t understand it. They fear it. So, if the rumours of the cache in the mountains are true, they will want to be rid of it. We’re going to solve their problem for them, and the jarl can pretend it was all his own plan. You are to embody an initiate of the Moon Clan: polished. Superior. Distant. Presence is a great magic. Both of you, remember what we’re doing here is of the utmost importance. If they have found a cache of runes, or even rune essence from the ages before, that will greatly benefit Lord Raddallin and thereby each of us. Ilme, leave the bags!”

“Yes, Master Endel,” Ilme said, taking off the pack she’d slung across her narrow chest, navigating around the half-pinned knot of her hair. She did not, however put back her scribe’s kit. That would not leave her side. She was careful, but it would only take one slip for the second lie to come out, and that would be very, very bad.

The sailors called that the boat was ready, and Master Endel gave the two young women one more assessment. “Azris, stop looking like you’ve smelt something unpleasant. Ilme, just… put the braid back. Come on.”

Ilme climbed down the side of the ship, settling in beside Azris on the leaky boat, and looked out across the last stretch of water. A great longhouse stood on the ridge overlooking the wide pebbled beach, the most prominent building in this seasonal village. But even that was built of skins and timber and slabs of peat. A dozen smaller structures surrounded it, like a gaggle of ducklings, but only the longhouse poured cook-smoke up into the cloudy air.

Below the longhouse the Fremennik had gathered on the beach itself, weapons in hand, their agitation and wariness so intense it seemed to stir the choppy waves between the little boat and the shore. Longships rested to the left of her, sleek bulks of wood ready to launch into attack. In their little boat, one sailor rowed and one waved a green cloth, like a flag of peace. This didn’t diminish the Fremennik’s wariness—Ilme wondered if they’d been tricked by false signs before.

Ilme made herself take a deep breath.

“I hear they sacrifice people,” Azris whispered to her, eyes on the Fremennik. “Put them on the fire and roast them alive. For demons. Maybe the Moon Clan don’t worship demons, but the Fremennik do. Everyone knows that.”

Ilme had heard this as well, but hoped it was a less credible rumour than the cache. “Master Endel said they were Guthixians,” Ilme whispered back. “Why would Guthixians roast people?”

Azris gave Ilme’s re-plaited braid a rough tug. “They’re maniacs. Who knows why they do anything?”

That was nonsense—Ilme was only sixteen and there was a lot she hadn’t seen and didn’t know, but if there was one thing she understood completely it was that people always had reasons for what they did. They might be foolish reasons, they might be dangerous reasons, and they might be reasons that people themselves didn’t know outright—but they were there. You could predict most things, if you listened and watched and uncovered the reasons.

Master Endel sat at the prow of the boat—polished, superior, and distant. When the boat hit the shore, he didn’t wait, but began walking up the beach toward the jarl. Azris climbed out after him, and Ilme followed, splashing through the icy shallows. By the time she’d made her way up the sliding stones of the beach, wet and stumbling, there was no hope of her embodying anything so fine as a mage of the Lunar Isle.

But Master Endel had already begun the lie to great effect. He approached the warriors on the beach, as unconcerned and steady as a ship cutting through calm water.

“I have come from across the Northern Sea to seek the counsel of Jarl Viljar,” he announced. “There is a disturbance in the magic of Gielinor and the Moon Clan wishes to resolve it to maintain the safety of all.”

The warriors glanced sideways at a pair of men—both young, both stern-faced, the same heavy brows, the same sharp noses. Brothers, Ilme thought. One was whip thin, with a pale beard and dark, sharp eyes. He wore a tunic embroidered with ferocious, beastly faces and a pectoral shaped like a sharp-toothed, horned face framed by axes. Over his shoulders he wore a wolf pelt, the hood fashioned so the wolf’s snout stuck out over his forehead, and summoning pouches hung around his waist. The other was dark-haired, his shaggy mane of brown hair flowing into his beard and down his furry shoulders. Two torques of braided silver were stacked on his thick neck, and he wore a helmet figured to look like a sneering, horned demon.

Ilme sucked in a breath.

“I might know what you speak of,” the dark-haired man said, not looking away from Master Endel. “What business is it of the Moon Clan?”

“Are we not the guardians of magic in this world?” Master Endel asked. “As much as I would never claim an axe, I don’t believe you wish to claim the runes. Will you take me to the jarl?”

The Fremennik muttered at this, and the pale-haired man made a sharp gesture. The dark-haired one spared the briefest of glances at Azris and Ilme, arranged on either side of Master Endel as they had practised, before saying, “We are not meant to interfere with the gods or their doings. Guthix has given us all we need to master our fates.”

“Which is why he has sent us to root out your conundrum,” Master Endel said. “Take me to your father.”

It was a neat trick, Ilme thought, as the men both paused, gazes flicking away from Master Endel. Who else could this pair be but the jarl’s sons, looking so alike and speaking with such authority? But they clearly hadn’t expected it to be so obvious; maybe they forgot how much they looked alike when one was light and one was dark. Now, Endel seemed far more a master of his art.

“I am Reigo Viljarsson,” the dark-haired man said. “This is my brother, Ott. If you are going to claim hospitality for the Moon Clan, then you will follow me and observe the rites.”

This was not in Master Endel’s plans—the hope was that they would recover the cache and leave as quickly as possible, no more than a day later, not lingering to let the Wolf Clan poke at their lie. But Master Endel was a quick-thinker, and he wanted the rune cache.

“Of course,” he said. “I have seen the paths and I forget to walk them. Lead on.”

The pale man started to object, but his brother shot him a look of irritation, and gestured for two warriors to flank Master Endel and guide him up the beach.

“Demon rites,” Azris whispered. Ilme watched Reigo and his ferocious helm lead the way up to the great longhouse.

The warriors fell in, and no one said what Ilme and Azris should do. No one had even acknowledged them. Ilme looked back at their abandoned luggage on the shoreline.

“Did you have a dream about this?” a voice asked. “Is that why you came?”

Ilme looked back and saw that one person hadn’t followed—a boy with yellow hair covering his ears, freckles, and dark, piercing eyes. He couldn’t have been more than twelve or thirteen, all elbows and angles and potential.

Azris lifted her chin in a fine mimicry of Master Endel. “We don’t discuss the visions.”

“We didn’t,” Ilme said, remembering the fine points of the lie. “We haven’t taken our final vows.” Was that right? Did Moon Clan mages take vows? Tests?

Azris shot her a dark look, as if Ilme had insulted her. “Anyway, it’s not your business, boy. Take the bags.”

The boy snorted. “Take them yourself, apprentice.”

Ilme stepped between them. “I’m Ilme. This is Azris. What’s your name?”

That question made a dark cloud pass over the boy’s face. “Gunnar Viljarsson.”

“You’re the jarl’s son?” Azris asked.

There was no hiding the scepticism in her tone, and his posture shifted into a mimicry of his brothers’. “He’s got three of us. Carry your own bags.”

“Well met,” Ilme said, giving him a courteous bow, and the boy relaxed a little. “Do you know where we’re meant to go now? Do we follow Master Endel?”

Gunnar frowned. “What else would you do?”

Ilme shrugged, nodding back at their supplies. “Put the bags somewhere. Prepare the beds. Like you said, we’re apprentices.”

“But you’re guests first,” Gunnar said. “What do you do to seal the guest rites?” He eyed them both. “Is it true you poison visitors and make them tell you all their secrets, and only let them stay if they survive?”

“What?” Azris cried. “That’s absurd.”

He shrugged. “It’s what they say.”

“We just don’t want to do anything wrong,” Ilme said, thinking she ought to avoid the Lunar Isle if even a breath of that were true. “It would reflect poorly on our master and insult your father.” She thought of his brothers’ temper, the boy’s bluster. “And we’d get in trouble,” she added, a gamble.

It paid off. Gunnar, clearly used to being overlooked until he made a mistake, made a face. “I can’t believe you came all this way and don’t even know how to do the guest rites. Come on. Bring your bags up to the longhouse and someone will put them in a tent.”

“Can you even imagine that little twig being a jarl’s son?” Azris whispered as Ilme picked up the bags. “He doesn’t look the part at all.”

Not yet, Ilme thought. But that was Azris—she saw the surface of the water and never wondered what was churning beneath it. The moment and not what followed after it. Gunnar was only a boy, and so clearly through with being a boy. That was dangerous—someone could use that.

Ilme felt a little sorry for him and found she hoped nobody else noticed how usable he might be.

“I wonder if he knows where it is,” Ilme whispered, as they climbed back up the beach.

“Where what is?”

“The cache. They don’t want to talk about it with us,” she went on, “but I bet they have talked about it. And they don’t pay him any mind. I’ll bet he’s heard things.”

“And I’ll bet if you ask him, he’ll go running to his father,” Azris said. “And then we’ll be in trouble. Sacrificed to the demons—did you see that helmet?”

Azris wasn’t wrong. But if Ilme asked Gunnar, she might find out first. She might be useful enough to keep Master Endel from asking her too many questions…

Gunnar didn’t offer to take any of the bags, but walked up the path, his posture slumping again. He pointed to a spot beside the great double doors of the longhouse, and then sloped inside without waiting for them. Ilme deposited everything except her scribe’s kit, and followed Azris and Gunnar in.

Inside, the longhouse was warm and crowded. There were no humans roasting on the fires, no blood sacrifices draining on the tables. Instead, Ilme watched the Fremennik turn clay pots perched on the fire’s edge with deft hands, dipping in wooden spoons to test barley porridge and boiled fish, spiky and fragrant with strange herbs. Others shifted domed loaves of bread around the fire’s edge.

There was, however, a demon at the end of the hall.

At the far, rounded end of the building, the jarl’s throne sat in the grasp of a monster—a horned man with a gaping mouth reached claw-like hands around the seat. Its eyes were dark mirrors, reflecting the firelight, the shadow of its maw beyond the throne a doorway into nothing. For a moment, it seemed to breathe, cold air bristling the hairs tugged loose from Ilme’s braid. Azris seized her arm with a hissed curse.

“Shut the door,” Gunnar said. “You’re making a draft.”

Ilme blinked, the spell shattered. It was a carving, a creature of painted wood and polished stone. She reached back and pulled the door snug in its frame.

“Demon worshippers,” Azris whispered.

The jarl sat on the throne between the clutching hands of the horned man. He was as pale as Ott, as big as Reigo, and as surly-looking as Gunnar. Through the thick pelt of his hair and beard, Ilme marked scars carving his skin—a ruler who’d seen battle. She glanced around the longhouse, marked other injuries, other scars—a clan that saw a lot of battle, she amended.

Shields hung on the long wall painted with figures that seemed twisted and wide-eyed. It took Ilme a moment to recognise them—a salmon, a mammoth, a wolf, a falcon, a seal—

“You sit there,” Gunnar said, pointing at a table against the long wall, beneath the seal shield.

“Our master’s up there,” Azris said. Master Endel stood before Jarl Viljar and his chosen warriors, and from where they now stood, Ilme could see a large green stone set between them. Reigo and Ott had settled down on a bench beside the throne, as the other warriors found seats nearer to the fire.

“You sit here because you’re children,” Gunnar said flatly, then after a moment, he sat first, seething.

“Children?” Azris demanded. “I’m nineteen!”

Gunnar’s freckled nose wrinkled in disgust, as if Azris had just admitted something shameful. “If you weren’t children,” he pointed out, “your master would have introduced you. And he didn’t. So you sit here.”

There was no further arguing with the jarl’s son: the buzzing blare of horns split the chaos of the longhouse, the Fremennik falling silent as Jarl Viljar stood before the stone and raised his arms, beginning a deep, throaty chant.

“There it is,” Azris murmured. “Sacrificial altar. Mark my words. I bet that summoner-son brings the demons in and they eat them alive.”

“You said they did it on the fires,” Ilme pointed out, but she couldn’t tear her eyes from the chanting jarl and the terrible face behind him. She leaned over to Gunnar. “What is he saying?”

“It’s the old tongue,” the boy said. “I don’t know all of it. It’s a prayer to Guthix, for strength and fortune in battle.”

Ilme nearly asked Gunnar to repeat himself—Guthix was a god of creation, of balance and promise. Order and responsibility. Not battle and blood and strength. But she peered closer at the green stone before the jarl’s throne and saw the faintly etched lines of teardrops covering the sharp-edged surface. The Tear of Guthix, as inarguably present as it was in the hanging talismans of the druids’ grove near her aunt’s hold or the stained glass of the wooden-walled shrine in Falador.

As Viljar chanted, warriors came forward, laying their axes, spears and bows against the stone with bowed heads, the clang and scrape of the weapons folding into the jarl’s chanting. Ilme eyed the older sons, Reigo and Ott, seated on the wall, their faces still tight and scornful. Ilme wondered which of them was meant to succeed Jarl Viljar, and which of them would actually do so, regardless of the jarl’s wishes.

Then she glanced at the jarl, his scarred face, and reconsidered. This was not a man who would back down easily.

But there were scores of hard faces, scarred and bearded and painted. “Have you had a war?” she whispered to Gunnar.

Again he looked at her, as if she were making fun of him. “We crushed the Seal Clan last season. They are under Jarl Viljar’s control now.”

Ilme glanced over her head at the row of shields. “That’s what all these are? Your… vassals?”

“Guthix!” Viljar bellowed, cutting off Gunnar’s answer. “When you stir, gods tremble! Where you walked, bounty blooms! You have raised mountains and leashed demons! You have granted the Wolf Clan the fiercest of warriors, the strongest of blades, the fruit of the field and the forest, and in turn we give these to our honoured guest—food, shelter, protection—that he might carry the word of the Wolf Clan back to his home.”

You’re safe while you’re here, Ilme thought. But tell everyone what a threat we are.

“This is weirder than a sacrifice,” Azris breathed. “It feels blasphemous. Why are they doing this now? Why are they talking about weapons?”

Viljar glanced down at Master Endel. “You are meant to lay your weapons on the stone,” his voice full of his sons’ disdain. “To grant your aid. But since the Moon Clan bear no weapons but their magic…”

Master Endel held up his hands as if offering to lay them on the stone. But Viljar waved this away, with the same nose wrinkle of disgust as his son. He beckoned to the Fremennik beside the fire, and pointed Endel to the bench beside his throne.

A woman came up bearing a clay plate of fish, barley and bread, offering it to Viljar. A man then carried over an empty plate, which he gave to Endel. Viljar spooned food from his own plate to Endel’s and gestured at him to eat.

The ritual complete, food was distributed through the longhouse, though there was still order and ritual here—Ilme charted the hierarchy of the Wolf Clan one dish at a time and watched as Ott reached for a plate, clearly handed to his brother first, a look of disgust flitting over his face. She saw Jarl Viljar spot it too, and frown deeply.

You’re observant, her aunt had said, only a month after Ilme had come to the hold, a month after the death of her father, I can use that.

Her aunt had something of the same keenness as the jarl, some of that same iron in her actions, rigid and uncompromising. She was the first person besides Ilme’s mother to realise she had a knack for reading people. But she had not asked what Ilme observed in her, any more than she’d asked if Ilme wanted to serve her.

Ilme, Azris, and Gunnar were among the last to eat, but there was still plenty. Ilme kept trying to catch Master Endel’s eye—but for the honoured guest there were more hosts to greet, more mead to drink, and no one seemed to remember that she and Azris were here as well. Ilme slipped a notebook and a stylus from her bag, marking down a few quick notes to herself about the Fremennik.

“What are you writing?” Gunnar asked.

Nothing she’d marked down was private, so she showed Gunnar the page. “I take notes for Master Endel,” she explained, and this much was not a lie. “You’re right—we don’t do things the same, and it’d be better if no one embarrassed themselves later.”

Gunnar scoffed. “You don’t need to write it. Just do it.” But she left the page open so he could read sidelong, still pretending he didn’t care.

“This is taking forever,” Azris said. She leaned across Ilme to speak to Gunnar. “How long do we have to stay?”

He blinked at her. “You… don’t? The rites are over. You’ve eaten.”

“That was it?” Azris said. She shook her head. “Fine. Can you just show us where we’re staying?”

This was clearly not what Gunnar wanted to do, but he searched the room as if looking for a replacement, and found instead the jarl’s stern gaze upon him. He hunched down again, before slipping from the bench. “Fine.”

Outside, the sky was still bright white as the sun bled through the cloud cover, but the brightness had dipped, angling toward sunset. They followed Gunnar through the camp to a tent near the shore. Casks and boxes stood against its wall—it had been a storage building, Ilme thought, before they arrived.

“Are we all in here?” Azris sniffed. “Fine. I’m going to read and go to bed. Don’t make any noise,” she added to Ilme.

“I want to walk around a bit,” Ilme said. “I’ll be quiet when I come back.”

“Suit yourself,” Azris said. “Don’t get thrown on any altars.” She ducked behind the door of skins. Ilme turned to Gunnar, who studied her with that same scowl.

“She seems like a wizard,” he said. “You don’t.”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, she’s rude and self-important,” Gunnar said, bluntly. “That’s what all the stories say. Wizards take magic and don’t give a care for what it costs. Who it hurts.” He paused. “Mages, I mean. Is that rude if I call you a wizard?”

“No.” Ilme thought back over the long course of history—through god wars and the fall of kingdoms, the gain and loss of magic. A long enough time, great enough changes, that anyone could be a villain. But having power certainly helped.

“That feels like most people with power,” she said. “But… yeah, wizards too. Although, I do know some nice ones.” She thought of Eritona, sick-abed, and hoped she was all right. They weren’t friends, Ilme knew, but Eritona wasn’t cutting like Azris, and she let Ilme look through her books. Though it was also easy to imagine her waking and saying that her stomach-ache had started when someone gave her a bitter cup of mead, and all eyes turning to the girl who replaced her…

Gunnar eyed her. “So are you a hopeless wizard then? Or a just a really tricky one?”

Ilme brought her thoughts back to the present. “I’m not really either. Mostly I just write things down,” she said. “Azris is Master Endel’s proper apprentice.”

Do what you’re good at, her aunt had said. Listen, watch, keep track. Report. Be still and silent and take it all in.

Ilme hesitated. What was the difference between manipulating someone and understanding them enough to predict them? She worried sometimes she didn’t know. But she thought in that moment that Gunnar deserved a little kindness, a little reminder that he wasn’t alone.

“I don’t… enjoy it very much,” she admitted, and the words gave her a frisson of panic. It was very close to admitting the second lie. “I think I’d like to be a wizard. It’s very interesting. But I’m no jarl’s son,” she added lightly, “so I take my lot.”

Gunnar was silent a moment. “Yeah, well… I don’t like being the jarl’s son very much.”

“Would you like to switch places?” she teased.

He rolled his eyes. “I think people might notice.”

“I don’t really envy you, though. You’ve got a lot of expectations on you.” Ilme considered before daring a little further, “Your father reminds me of my aunt a little. I feel like if I were her heir I’d wake up feeling like I’d failed already. You’re doing a lot better than I would.”

Gunnar heaved a sigh. “He doesn’t have an heir. He won’t just choose Reigo and be done. I’d rather leave anyway, explore the world. Do something interesting. But I can’t. He might choose me. I have to stay here and wait.”

He might choose no one, Ilme thought. She hesitated, and then offered him the only gift she had: “What about your other brother? Ott?”

“Ott?” he said, confused. “Wolf Clan doesn’t have summoner-jarls.”

“If your father takes too long… if he doesn’t choose…” Ilme said. “Just a… mage’s sense, I guess. He seems to want the throne most. And I think you know your father might never choose, so that won’t be peaceful.” She shrugged. “I suppose if you wanted to slip away before Ott did anything, he probably wouldn’t chase you. You could both get what you want.”

Gunnar blinked at her. “He’ll probably choose Reigo anyway.” He kicked a rock down the short cliff, staring out at the sea. Then he seemed to make up his mind and turned to her. “Do you want to see something?”

“Depends,” Ilme said. “What sort of something?”

Gunnar glanced past her at the longhouse. “You came about the rift. The rune stuff. I know where it is. We could go see it now.” When she hesitated, he added, “You’re done, but they’re going to go late into the night. If you didn’t know. He’s got to drink a lot of mead.”

“I don’t think Master Endel knew that either,” she said. “Is it far?”

Gunnar gave her boots an appraising look. “Dunno. You live on the island. Nothing’s far to you. Are you gonna give up if it’s too far?”

“Are you going to make me walk five leagues to see a quarry?”

He grinned at her. “Oh, it’s better than a quarry. But you have to climb.”

* * *

Ilme was sweating by the time they reached the top of the cliff, the light growing orange with the setting sun. Several times she had nearly asked to turn back, but the chance to see the rune essence cache before Master Endel was too precious. And if she could bring back information—good information—she might have a little more reprieve.

Ilme looked back the way they’d come—the longhouse and the camp full of torches seemed so tiny. “How did you find this place?”

“Egg hunting,” Gunnar said. “Seabirds nest in the cliffs. Come on.”

This high up, snow still crusted the rocks where the shadows lay deep and unshifting. The sweat on Ilme’s skin chilled quickly and she pulled her new green cloak closer around her shoulders as she followed Gunnar up a path that curved around the next steep rise. It came out into a flat field, the snow lying like lace over patches of green-grey grass. Ahead, there was a dark crack in the earth.

Something in Ilme shivered, something very unlike the cold.

Ilme peered down at the crack in the earth. “How… How big is it? The cave or… what is it?”

“Come on,” he said again, reaching back to take her hand, and for a moment he felt so much younger than her, so very far from where she stood. “Just follow me,” he said, seeing her discomfort. “I’ll go first.”

Gunnar showed her where to put her feet, what to hold onto as she descended into the dark space. A faint, warm breeze gusted up from the cleft, like the breath of a giant beast and she thought of the demonic face in the longhouse and wondered where its likeness had come from.

“Do you have a light?” Ilme asked.

He snorted. “You don’t need one.”

That shiver built inside her as she descended one careful drop at a time, as if something were stirring deep down, waking from dormancy. It was unsettling—like dark things in the water, and no one to name them. Ilme liked safety, liked predictability. That some unnameable part of her was reacting to the strange cave felt terrifying.

Maybe it means there’s more down here than Master Endel thought, she told herself. Maybe enough to take some for yourself. That would certainly gain her a reprieve…

The light above shrank quickly as they descended, a tiny window to the world… but then the darkness didn’t close around her the way she’d expected. A faint light filled it, a soft, hazy glow that came from all around. When she stepped off at last to land at the bottom of the shaft, she found she could see Gunnar without any trouble.

And every inch of her skin felt as if it were humming.

“What is that?” she asked, her breath coming too fast. “What’s doing that?”

“You’re not scared are you?” Gunnar asked. “You shouldn’t be. I’ll protect you. I can… I think I could kill it. If I had to.” He straightened, shoulders out, as if he could be as big and muscular as his brother.

His words didn’t make sense, but Ilme couldn’t order her thoughts to tell him so. She laid a hand against the wall of the cave, the same way she might lay a hand against the flank of a strange horse. The wall was only stone, but that unsettling tug on her senses didn’t stop. “You don’t feel it?” she whispered.

“Feel what? The rock?”

You need to get out of here, she told herself.

A cold voice that sounded like her aunt’s cut through the worry. If you leave without seeing anything, you will lose your chance. That jarl will never let you near here if he has his way.

Gunnar grabbed her arm again, tugging her into the dim tunnel. “Come on. Don’t be scared.”

It was like a dream. The strange glow in the air, the winding crack of a path, the boy with his golden hair shining like a torch as he pulled her on and on. The echoing pull in her, like a song she didn’t know, in a tongue too ancient and foreign for her to understand. And Ilme, who had always been so skilled at knowing what lay in others, who read their fears like a book, suddenly wasn’t sure of what lay inside herself.

The path opened into a wide cave, faint sounds of water echoing off walls lost in the dim light, and Gunnar stopped, dropping her hand and setting his own hand on the knife he wore. The stones here glimmered, pulling harder on her. No… not all the stones. She reached for one, felt the lurch in her chest toward it. It was smooth, silky almost, but so ordinary looking.

“Is this—” Ilme began. But Gunnar hushed her and pointed into the shadows.

In the darkness, two great luminous eyes opened, and something massive shifted into motion. She knew she ought to run, ought to flee that huge creature, but shock stopped her feet from responding.

“Well,” a great, sonorous voice said, strangely gentle despite the size of the speaker, “you’ve returned, little mortal. And what have you brought? Hm? I hope you don’t mean her as an offering—not at all to my taste.” A deep rounded laugh boomed through the cave as the speaker pulled itself forward.

Ilme blinked, unable to make herself speak. It was a frog—a frog as tall as a longhouse, patterned with pale green and dull purple patches, a droplet like a tear outlined in vibrant blue between its bulging eyes.

A guardian, Ilme thought feeling lightheaded. A Guardian of Guthix. They were said to stand over places of great power, great magic. Wardens of the sleeping god’s gifts.

I could kill it, Gunnar had blustered. And all Ilme could think was, I wouldn’t let you.

Gunnar didn’t answer the creature, suddenly shy. It hitched itself forward, gazed on Ilme. “Welcome, child,” the guardian said. “I am Zorya.” It blinked its enormous eyes at her. “Have you come to reclaim the gifts? To bind again the rune magic?”

“How… How long have you been here?” The question was out of Ilme’s mouth without thinking—what did it matter? What should she say?

Zorya’s throat pulsed, a deep thrum echoing in the cave. “Mmmm, long enough. Because here you are, Ilme! And here I am, and here are the gifts of Guthix! You have great works ahead of you!”

“How… How do you know my name?” she said, small and fragile. This was not Master Endel’s tricks, not the jarl’s show of power. If the guardian knew her name, what else did he know?

Zorya thrummed. “Because it’s your name, of course. Now: how much do you know about rune magic? Where should we begin?”

“I…” Ilme swallowed. “I don’t think I’m the one you’re looking for. My master—”

“Your master is not here,” Zorya pointed out. “You are. But let him come—let them all come. After centuries of upheaval the world is in balance. Great changes are upon you! Humanity has been like the tadpole in the mud, but now it must grow its legs and take to the new world! I am so very delighted to be able to help you.”

“Is that what the god wants?” Ilme asked, numbly.

Zorya’s thrumming held a strange hesitancy this time. “I think so,” he said.

Ilme shivered once more and hesitantly picked up one of the stones. “Is there enough rune essence to make a difference?” she asked. “How much did our ancestors cache here?”

Zorya thrummed again, and this time it sounded like laughter. “Oh dear, little mortal! This isn’t some dead soul’s treasure trove. It is the gift of Guthix.”

Ilme shook her head. “I don’t understand.”

The enormous frog lowered itself, to peer at her. “This will be a mine. A rune essence mine. A vein that runs deep into the ground. I have guarded it against the legions of Bandos and the seeking hands of worse things. There is enough here to carry you through the next age and beyond. Enough to teach humans magic once again.”

For a moment, Ilme couldn’t breathe. A whole cave of rune essence—she thought of all the spells Master Endel and Azris went on about, the way things had been so long ago. Rune essence condensed into runes: if you didn’t have to scrounge and steal scraps of essence, if you had an endless mine, then you could have endless runes, endless magic.

She imagined herself, briefly, casting walls of fire and dizzying spirals of magic to tangle an enemy’s mind. She imagined herself, facing down her aunt—

“It’s customary,” the guardian went on, “to bring an offering.” The pale sac of his throat pulsed again. “I’m rather fond of sweets,” he added, meaningfully.

* * *

When Ilme closed her eyes, Zorya’s own great glowing eyes filled her mind, the resonance of the rune essence humming in her core. All through the night and the next days, all the way back to Falador on the other side of the mountains.

Master Endel hadn’t been pleased that she’d gone off with the jarl’s son, but when she brought tales of a Guardian of Guthix and the rune essence she’d taken from the cave, his manner changed. When he went to inspect the cave with Jarl Viljar, Endel expressed no surprise at the guardian, none of the excited energy he’d shown when Ilme showed him the rune essence she’d found. Polished, superior, and distant as he visited Zorya and offered up a thick, syrupy bean cake unasked. The guardian had been delighted.

“I will manage this for you, jarl,” Endel said. “You need not trouble yourselves with the rune essence.” There would be agreements of passage for Endel and his agents to travel to the mines, of course, the hospitality of the Wolf Clan bought with goods and gold.

“Master,” Ilme asked, when the Wolf Clan’s cold shores had faded from view. “What happens if they realise that it’s not all Moon Clan mages coming for the rune essence?”

Master Endel waved this away. “The Moon Clan is very busy and hires outlanders to cart stone. What’s surprising about that? Anyway, if the jarl finds out, he will still be glad to have this dealt with and all the weapons and goods it gained him. He has his eyes on the northern island clans and what he can gain there—he’s not looking south.” All the polish was gone, his voice bouncing with energy and joy. “Lord Raddallin will be pleased,” he told her. “We have quite a homecoming ahead of us.”

TWO

THE SEVENTH YEAR OF THE REIGN OF LORD RADDALLIN OF THE DONBLAS TRIBE

THE SECOND DAY OF THE IRE OF PHYRRYS

FALADOR

Lord Raddallin was not pleased.

“Explain to me how this is to our benefit,” he said, once Master Endel had told the story of the voyage and rune essence discovery, reading Ilme’s report almost word for word. “You have been gone for months in search of runes, and what you have to show for it are…” He gestured at the rune essence laid on the table before him. “Rocks?”

Master Endel was not a large man, but beside Raddallin, all men looked small. The lord of the Donblas Tribe was a tower, a fortress unto himself; even when sitting down at the table in his war room, he filled the space and drew the eye.

When Raddallin claimed he would raise Asgarnia from the ashes of history, that he would unite the tribes into a kingdom, it seemed inevitable.

To some people, Ilme amended. There were many tribes in Asgarnia, many warlords, and even though Raddallin had succeeded in uniting the Eastern tribes against the nearby kingdom of Misthalin, he had not exactly brought all of them to heel. But, tucked as she was in the shadows of the war room, she said nothing of the sort.

“Not rocks, my lord,” Endel said. “Rune essence. A mine of rune essence that only we know about. With this, you can make new runes—any runes. It is far more valuable than a cache of already crafted runes.”

In the court of Falador more than anywhere, Ilme thought, Endel’s ambition stood out, like grasping vines trailing all his words. He had come from Misthalin, frustrated at its rigidity and disinterest in his studies toward rebuilding rune magic, and found Raddallin full of all the ambition Misthalin had thwarted in Endel. It bloomed in him now, as if Raddallin were the sun.

She knew Raddallin was not dismissing Endel—he wanted to understand how things had changed, wanted to meet Endel where he stood now: excited about what seemed like a pile of gravel. But others at the table were not so open.

“Have you not already sources of power to craft runes from, Master Endel? Is that not your entire role here?” Beside the would-be king, Adolar, Grand Master of the White Knights, was a pale reflection, all bone and blond hair. He wore his armour as if he were born in the shell of it, and all the severity of his god, the bright lord Saradomin, seemed to radiate from his expression and clamp down on his shoulders in equal measure.

Ilme could imagine Adolar in another place, another time, ruling a tribe of his own with a fist of iron. Not a great ruler, Ilme thought. If Adolar stood in Raddallin’s place, no ambitious wizards or powerful chieftains would turn toward him—he was all he would ever be. He would hold the reins of power firmly, but never be so bold as to reach farther, to ask what else can I achieve? Where Raddallin drew the eye and stirred a need to be recognised in people, Adolar merely made one feel as if he were already disappointed in them.

Adolar’s White Knights had once been fully allied with the Kingdom of Misthalin. Once, the White Knights had counselled Lord Raddallin to swear fealty to Misthalin, to its strong army and its clever wizards scraping magic from the corners of the world.

Another sign Lord Raddallin is destined for something greater, Ilme thought, continuing to write down the words they were speaking from the dim corner of the room. The Saradominists have bent to him.

Master Endel turned to Adolar. “The sources I have cultivated are dangerous and difficult to draw from. And, more importantly, limited—they can only be what they are already. If you want fire, I must take from the fire. If you want ice, I must take from the ice.

“But the rune essence is unbound—it can become anything. It can become many things at once. Easily and without risk.”

Adolar poked at the grey and unassuming stones. “This?”

“Think of it,” Endel said, eyes only on Raddallin. “Your armies supported by spells of power in combat. Falador, not just a warlord’s holding but a fortress of renown, a shining city on the mountain built as easily as breathing.”

“Easily as breathing? That would be quite something,” a woman’s mocking voice called out, and dread poured over Ilme.

Sanafin Valzin, Marshal of Falador, First Lord of the Kinshra, swept into the hall like a raven diving from a high perch. Her boots clicked against the stone floors, her scabbard clinking against her sword belt. Her close-cropped black hair shone like a feathered helmet, her blue eyes gleaming in a pale face. Where Adolar was severity itself, Valzin was all deftness and motion. Here was the reason Raddallin defied Misthalin and the White Knights. Here was the first spark in the fire of his campaign. Here was the fire that lit Raddallin’s own ambition.

She made Ilme’s nerves itch, never certain what Sanafin Valzin was really doing.

In this, Ilme was not alone. Adolar looked up with a scowl and Master Endel did not turn but made fists of his hands. Only Raddallin seemed at ease, a little annoyed perhaps, but also a little amused.

“Sana,” he chided, “you’re late.”

“My apologies, my lord,” she said, dropping into a bow. “Your Black Knights were busy teaching the Massama Tribe to mind their manners.”

“Lord Keerdan?” Adolar said frowning. “He said she would accept Lord Raddallin’s rule.”

“Yes well, it also seems he’s saying similar things to Moranna of the Narvra. To the tune of a hundred fresh spears. Pity he doesn’t have them anymore.” She grinned at Adolar. “Don’t fret. Now we’re even. I missed the Kareivis Tribe talking to Misthalin, and you missed Lord Keerdan. And you—”she turned to Endel, “—have been busy.”

“Since you did not join us, Marshal,” Endel said stiffly, “you shall have to wait until I am finished—”

Valzin waved this away. “I read your scribe’s notes on the way up. I have the broad strokes.” She smiled at Ilme, who froze, suddenly visible. That, too, was Valzin—you never knew what she was watching. It benefitted Lord Raddallin to have an ally that moved in unexpected ways… but there were rumours among the White Knights that Sanafin Valzin wasn’t loyal to Raddallin, but to the dark powers of her god, Zamorak.

If that were the case, Ilme thought, Valzin was doing an admirable job of obscuring herself. To all eyes, she was Raddallin’s most devoted advisor. By all actions, too. And you could find the same whispers about the White Knights, their loyalty to their god and Misthalin, their former master. There was gossip everywhere.

“Now then,” Valzin went on to Endel, “you don’t have a way to create runes from the rune essence. You need the altars built in ages past to create so much as a puff of wind, let alone this easily-as-breathing crafted city-fortress.”

“I was getting to the altars,” Endel began.

“Perhaps get to them now,” Raddallin said, patiently.

Endel blew out a breath. “To bring this plan to fruition, we would need to find and restore the rune altars—sites scattered across Gielinor which were said to be built by a Fremennik seer called… Never mind. You don’t need the history. They were built and later destroyed. Restoring them is the most efficient, safest, and simplest way to create new runes. We have detailed information on how they should work.”

“Once they’re fixed,” Valzin said.

“Where are these rune altars?” Raddallin asked.

“Scattered across Gielinor. We would need to mount an expedition to locate them.”

“For which you need an escort,” Valzin said, taking a seat at the table almost directly opposite Ilme, on Raddallin’s farther side. “Which is to be? Adolar’s knights or mine?”

Adolar stiffened. “I dislike the idea of taking forces away from Falador. The White Knights are needed here.”

“Interesting,” Valzin said. “That suggests to me at least, that you also have concerns about this venture. I can’t imagine you saying the Kinshra should be sent after sources of great magic if you thought they were likely to be everything Endel’s hoping for.”

Adolar sniffed. “You’re baiting me, Marshal.”

“Never,” she said, with a smirk. She turned to Endel. “What you’re looking for has been lost and probably broken for ages. If you find the altars, do you know how to fix them?”

“I don’t expect it to be complex,” Endel said, eyeing Grand Master Adolar as if weighing Valzin’s casual accusation. “Their locations are referenced in Julyan’s Catalogue of Ancient Advancements. Once we locate the first, I have records of the rituals done in ancient times to create them—restoration will take some experimentation, but it should fall together.”

“And then you can make runes?” Raddallin asked.

The barest hesitation, and then, “I believe so.”

“But you don’t know,” Adolar surmised.

“To be fair,” Valzin added, “how could one know if they have the ability to refresh a lost holy site?” She smiled at Endel, and it put Ilme in mind of a cat. “One presumes if you find the altars, if you repair them, you can convert all your rune essence into runes—ideally ones which will grant runes to speed along Lord Raddallin’s unification?”

“Of course,” Endel said. Then to Lord Raddallin, he added, “There are some… vagaries in the records. Each altar attunes a specific elemental energy into the runes. I am confident in the locations of some of these, while others will be a gamble. And some will be unreachable until we can make diplomatic arrangements.”

“I find fire is convincing to an obstinate enemy,” Lord Raddallin said. “Do you have that one?”

Master Endel gave Raddallin the same pinched smile he’d given the jarl when he’d asked after his weapons. “Of course, my lord. Although there are a great many other options besides fire.”

“You have the floor, wizard,” Raddallin said, gesturing expansively at the room. “Regale us.”

Here at least, Master Endel was on firmer ground. He described runes of air and earth and ice, of body and mind, law and chaos, and more. He enumerated spells that could be crafted out of their combinations—blasts of fire, yes, but also spells to befuddle foes or sap their energy. Spells to make short work of building outposts and new fortresses. A world where almost anything was possible.

“Is the mine secure?” Adolar asked. “What happens when the Fremennik decide they want to reclaim access to the essence?”

“They won’t,” Endel said firmly. “They are well paid, and they aren’t interested in magic. The jarl has his mind on his own unification schemes and there are many other clans to pursue.”

“For the moment,” Raddallin said. “But that’s nothing we can’t manage. Especially if we have the runes to work with.”

Valzin eyed Endel speculatively. “Is it possible that Moranna of the Narvra has rune magic we don’t know about?”

Endel frowned. “If she has, she’s not used it.”

“Would you know?”

“What are you getting at, Sana?” Raddallin demanded.

“A mere notion,” Valzin said, with a shrug. “It sounds as if it can do almost anything. And we do find Moranna ahead at every turn.”

“Not every turn,” Raddallin said.

“My apologies,” she said. “She’s still a thorn in your backside that no one can pull. You can’t deny that. So how is she managing it?”

No one answered—no one knew. Of all the warlords of the Asgarn, Moranna of the Narvra Tribe seemed the most insurmountable obstacle to Raddallin’s rule. They called her the Ghost of the Eastern Reaches—what she lacked in valuable territory, she made up for with an uncanny ability to be everywhere at once, whispering in every Marshal’s ears, driving back every ally Raddallin made.

Ilme dipped her quill in the inkpot, slow and thoughtful, her stomach in knots.

You are observant and obedient, her aunt had said. And very easy to overlook—no one thinks much of a girl your age. This is how you will earn my protection. Lord Raddallin is trying to destroy everything we stand for—and if you want to live, you will help me see to it that the Narvra aren’t crushed under his ambition.

She will want to hear about the rune essence mine soon, Ilme thought, adding another line to the record. She recalled Zorya’s great glowing eyes and the tear of Guthix, and his warning: Humanity has been like the tadpole in the mud, but now it must grow its legs and take to the new world… or it will perish. No hint of what the right path would be for Ilme herself. No sense of how she would weather this.

She glanced up at Raddallin. Moranna might be the stronger warlord—the Narvra might be more intimidating, perhaps even more skilled as warriors, but she had come to think only Raddallin could be a monarch. Moranna reacted—not acted. In the absence of this foe, she would not dare anything so great as unifying the tribes. She would pretend it was in their nature to stay, small and fighting. Moranna was incapable of imagining a united Asgarnia.

But Moranna would never admit it, and Ilme would never speak it—that would only lead to her destruction. She studied the rune essence laid before Lord Raddallin, the strange tug of it quieter now that she’d gotten used to it. She imagined how different things would be with the powers Master Endel had described in her hands… She could make Moranna forget her, make herself invincible, burn down her aunt’s war room…

Endel rapped his knuckles against the stone table, startling Ilme. “If we access the runes, we can ferret out her sources. That much I can promise.”

“Or simply lay waste to her armies with fire and ice,” Valzin said cheerfully. “As you said, easy as breathing.” She grinned at Ilme, her blue eyes dancing. “Make sure you write that down.”

* * *

Ilme reviewed her notes with Master Endel in the war room once the others had left, adding a few matters that had occurred to him. She finished and looked up to verify that she could go. Master Endel was studying her, a thoughtful expression on his face.

“There’s another matter we should discuss, I think,” he said. “You can feel the magic in the rune essence?”

She’d already admitted as much when she described the essence mine, so there was no point in lying to him just to get away quicker. “Yes, Master Endel.”

“What exactly do you notice?”

“A… It’s a sort of… pulling? Like someone has a hook in me? In the core of me? But it doesn’t hurt.”

He winced at her clumsy explanation. “Azris tells me she caught you several times onboard the ship, standing beside the crates. She was rather sure you were stealing it.”

Ilme flushed. “No, master, I just… I was curious.”

“Curiosity is an excellent attribute,” he said. “I wonder if it’s more.”

“I don’t know what you mean,” Ilme said, feeling her cheeks burn. There was nothing about standing near the essence just to feel that deep-down pull that would lead Endel’s back to Moranna and her connection to Ilme—was there?

“I think,” he said, kindly now, “that you find yourself drawn to it. That perhaps you have an inborn knack. Have you considered studying to be a wizard? If all goes well, Lord Raddallin will be pressing me to expand our ranks. And quickly.”

Ilme startled. “Oh.”

Endel frowned. “That’s not a yes.”

It wasn’t. How could she agree to study with him if they were already aware Moranna had a spy inside Falador? She might want very much to be a wizard, she might have felt the draw of the rune essence. But if she studied with Master Endel she would no longer be invisible.

And if she said outright that she didn’t want to learn, he would know she was lying.

“It’s a great honour,” Ilme said. “I… May I think about it?”