Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

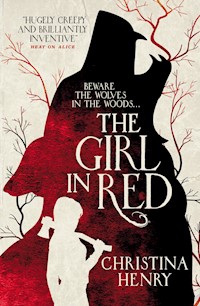

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

From the New York Times bestselling author of Alice and Lost Boy comes this dark retelling of Red Riding HoodIt's not safe for anyone alone in the woods. But the woman in the red jacket has no choice. Not since the Crisis came, decimated the population, and sent those who survived fleeing into quarantine camps that serve as breeding grounds for death, destruction, and disease. She is just a woman trying not to get killed in a world that was perfectly sane and normal until three months ago.There are worse threats in the woods than the things that stalk their prey at night. Men with dark desires, weak wills, and evil intents. Men in uniform with classified information, deadly secrets, and unforgiving orders. And sometimes, just sometimes, there's something worse than all of the horrible people and vicious beasts combined.Red doesn't like to think of herself as a killer, but she isn't about to let herself get eaten up just because she is a woman alone in the woods…

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 426

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Beliebtheit

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Praise for The Mermaid

Praise for The Lost Boy

Praise for Alice

Praise for Red Queen

Also by Christina Henry and available from Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter 1 The Taste of Fears

Chapter 2 All Our Yesterdays

Chapter 3 Toil and Trouble

Chapter 4 Hide Your Fires

Chapter 5 Daggers in Men’s Smiles

Chapter 6 What’s Done Is Done

Chapter 7 The Grief That Does Not Speak

Chapter 8 The Serpent under It

Chapter 9 The Dearest Thing

Chapter 10 Sound and Fury

Chapter 11 The Hurlyburly

Chapter 12 A Walking Shadow

Chapter 13 Brief Candle

Chapter 14 Something Wicked

Chapter 15 Supped Full with Horrors

Chapter 16 Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow

About the Author

PRAISE FOR

THE MERMAID

“Beautifully eloquent language…and the credible historical setting will draw readers into this lovely reimagined fairy tale.”

Booklist (starred review)

“This tale has a wicked bite underneath its elegant surface.”

SciFiNow

“At times it’s an horrific tale of greed, exploitation, titillation and prejudice, but it’s told with such simplicity and warmth that you can’t help falling in love with the mermaid.”

The Fortean Times

“Beautifully written and daringly conceived, The Mermaid is a fabulous story…Henry’s spare, muscular prose is a delight.”

Louisa Morgan, author of A Secret History of Witches

“What The Mermaid accomplishes – and accomplishes very well – is a convincing marriage of history with fairy tale, as well as examining what it means to be human without ever really feeling a part of the human world.”

Starburst

PRAISE FOR

THE LOST BOY

“Christina Henry shakes the fairy dust off a legend; this Peter Pan will give you chills.”

Genevieve Valentine, author of Persona

“Multiple twists keep the reader guessing, and the fluid writing is enthralling…This is a fine addition to the shelves of any fan of children’s classics and their modern subversions.”

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“This wild, unrelenting tale, full to the brim with the freedom and violence of young boys who never want to grow up, will appeal to fans of dark fantasy.”

Booklist

“Turns Neverland into a claustrophobic world where time is disturbingly nebulous and identity is chillingly manipulated… [A] deeply impactful, imaginative, and haunting story of loyalty, disillusionment, and self-discovery.”

RT Book Reviews (top pick)

“We all have a soft spot for the classics that we read when we were growing up. But… this retelling will poke and jab at that soft spot until you can never look at it the same way again.”

Kirkus Reviews

PRAISE FOR

ALICE

“I loved falling down the rabbit hole with this dark, gritty tale. A unique spin on a classic and one wild ride!”

Gena Showalter, author of The Darkest Promise

“Alice takes the darker elements of Lewis Carroll’s original, amplifies Tim Burton’s cinematic reimagining of the story, and adds a layer of grotesquery from [Henry’s] own alarmingly fecund imagination to produce a novel that reads like a Jacobean revenge drama crossed with a slasher movie.”

The Guardian (UK)

“[A] psychotic journey through the bowels of magic and madness. I, for one, thoroughly enjoyed the ride.”

Brom, author of The Child Thief

PRAISE FOR

RED QUEEN

“Henry takes the best elements from Carroll’s iconic world and mixes them with dark fantasy elements… [Her] writing is so seamless you won’t be able to stop reading.”

Pop Culture Uncovered

“Alice’s ongoing struggle is to distinguish reality from illusion, and Henry excels in mingling the two for the reader as well as her characters. The darkness in this book is that of fairy tales, owing more to Grimm’s matter-of-fact violence than to the underworld of the first book.”

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

Also by Christina Henry and available from Titan Books

ALICERED QUEEN

LOST BOY

THE MERMAID

LOOKING GLASS (APRIL 2020)

THE GHOST TREE (SEPTEMBER 2020)

The

GIRL IN RED

Christina Henry

TITAN BOOKS

The Girl in RedPrint edition ISBN: 9781785659775E-book edition ISBN: 9781785659782

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First Titan edition: June 201910 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © 2019 Tina Raffaele. All rights reserved.

www.titanbooks.com

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Rebecca Brewer,because some heroines have a cupcake stashinstead of wearing a cape

CHAPTER 1

The Taste of Fears

Somewhere in an American forest

The fellow across the fire gave Red the once-over, from the wild corkscrews of her hair peeking out from under her red hood to the small hand axe that rested on the ground beside her. His eyes darted from the dried blood on the blade—just a shadow in the firelight—to the backpack of supplies next to it and back to her face, which she made as bland as rice pudding.

Red knew very well what he was thinking, what he thought he would be able to do to her. Men like him were everywhere, before and after the world fell apart, and it didn’t take any great perception to see what was in their eyes. No doubt he’d raped and murdered and thieved plenty since the Crisis (she always thought of it that way, with a capital letter) began. He’d hurt those he thought were weak or that he took by surprise, and he’d survived because of it.

Lots of people thought that because she was a woman with a prosthetic leg it would be easy to take advantage of her—that she would be slow, or incapable. Lots of people found out they were wrong. Someone had found out just a short while before—hence the still-bloody axe that kept drawing the attention of the stranger who’d come to her fire without invitation.

She should have cleaned the blade, though not because she was worried about scaring him. She should have done it because it was her only defense besides her brain, and she ought to take better care of it.

He’d swaggered out of the trees and into the clearing, all “hey-little-lady-don’t-you-want-some-company.” He had remarked on the cold night and how nice her fire looked. His hair was bristle-brush stiff and close to the scalp, like he’d shaved it to the skin once, but it was growing out now. Had he shaved it because he’d been a soldier? If he had been, he was likely a deserter now. He was skinny in a ropy muscled way, and put her in mind of a coyote. A hungry coyote.

He didn’t look sick; that was the main thing. Of course nobody looked sick when they first caught it, but pretty soon after they would be coughing and their eyes would be red from all the burst blood vessels and a few days after the Cough started, well . . . it was deceptively mild at first, that cough, just a dry throat that didn’t seem to go away and then it suddenly was much more, a mild skirmish that turned into a world war without your noticing.

It didn’t escape Red’s notice that underneath his raggedy field coat there was a bulge at his hip. She wondered, in a vaguely interested sort of way, if he actually knew how to use the gun or if he just enjoyed pretending he was a man while flashing it around.

She waited. She wasn’t under any obligation to be polite to someone who thought she was his next victim. He hadn’t introduced himself, although he had put his hands near the fire she’d so painstakingly built.

“Are you . . .?” he began, his eyes darting over her again. His gaze paused for a moment when he saw the gleam of metal at her left ankle, visible just beneath the roll of her pants.

“Am I what?” she asked. Her tone did not encourage further conversation.

He hesitated, seemingly thinking better of it, then gestured at his face. “Your eyes are light, but your skin is brown. You look like you’re half-and-half.”

She gave him her blandest glance yet, her face no more expressive than a slice of Wonder Bread.

“Half-and-half?” she said, pretending not to understand.

Red had that indeterminate mixed-race look that made white people nervous, because they didn’t know what box to put her in. She might be half African or Middle Eastern. She might be a Latina or maybe she was just a really dark Italian. Her eyes were an inheritance from her father, a kind of greenish blue, and that always caused further confusion.

Their eyes always flicked up to her hair, looking for clues, but she had big fat curls that could have come from anybody. She was used to speculative glances and stupid questions, having dealt with a lifetime of them, but it always surprised her (it shouldn’t have, but it did) how many people still cared about that dumb shit when the world was coming to an end.

“I was just wondering what—” he said.

“Where I come from it’s not polite to start asking people about their folk before you’re even introduced.”

“Right,” he said. The intruder had lost some of the swagger he’d had coming into the clearing in the first place.

“What are you doing out here on your own? I thought everyone was supposed to go to the nearest quarantine camp,” he finally said, choosing not to introduce himself despite her admonishment.

They were not going to be friends, then. Red did not feel sad about this.

“What are you doing out here on your own?” she answered.

“Right,” he said, shuffling his feet. His eyes darted in all directions, a sure sign that a lie was on offer. “I lost my friends in the dark. There were soldiers and we got separated.”

“Soldiers?” she asked, sharper than she intended. “A foot patrol?”

“Yes.”

“How many soldiers?”

He shrugged. “I dunno. A bunch. It was dark, and we didn’t want to go to the camp. Same as you.”

Don’t try to act like we have something in common. “Did you come from the highway? Do you know which way they were headed? Did they follow you?”

“No, I got away clean. Didn’t hear any of them behind me.”

This sounded like something he’d made up to explain the fact that he was alone in the woods with no supplies and no companions and sniffing around her fire looking for something he didn’t have.

Red sincerely hoped he was as full of shit as he seemed, because she was not interested in encountering any soldiers. The government wanted everyone rounded up and quarantined (“to safely prevent the further spread of the disease”—Red had snorted when she heard that announcement because the fastest way to spread disease is to put a whole bunch of people in tight quarters and those government doctors ought to know better) and she didn’t have time for their quarantine. She had to get to her grandmother, and she still had a very long way to go.

Red had passed near a highway earlier in the day. The experience filled her with anxiety since soldiers (and people generally) were more likely to be near highways and roadways and towns. She hadn’t encountered a patrol there, but she’d had a small . . . conflict . . . with a group of three ordinary people about two or three miles into the woods past the road. Since then she’d tried to make tracks as fast as possible away from anywhere that might be populated. Red wasn’t interested in joining up with a group.

She hadn’t asked the coyote to sit down and join her, and it was clear he didn’t know what to do with himself. Red could see the shape of what he figured would happen on his face.

He’d thought she would be polite, that she would offer to share her space with him. He’d thought she would trust him, because she was alone and he was alone and of course people were pack animals and would naturally want to herd together. Then when her guard was down or maybe when she’d fallen asleep, he’d take what he wanted from her and leave. She was not following his script, and he didn’t know how to improvise.

Well, Red’s mother hadn’t raised a fool, and she wasn’t about to invite a coyote to sit down to dinner with her. She stirred the stew over the fire and determined that it was finished heating.

“That smells good,” he said hopefully.

“Sure does,” Red replied. She pulled the pot off the fire and poured some of the stew into her camp bowl.

“I haven’t eaten a darn thing since yesterday,” he said.

Red moved the bowl into her lap and spooned a tiny bit of stew, just a mouse bite, into her mouth. It was too soon to eat it and hot, far too hot, and it scorched her tongue. She wasn’t going to be able to taste anything for a couple of hours after that, but she didn’t show it. She only looked at him, and waited for whatever it was that he was going to do.

He narrowed his eyes then, and she glimpsed the predator he’d tried to disguise under a charm mask.

“Where I come from it’s polite to share if you’ve got food and someone else doesn’t,” he said.

“You don’t say.”

She spooned up some more stew, never taking her eyes from him. She was going to lose what was in the pot in a minute when he charged at her, and she was sorry for it, for she was hungry and it wasn’t easy to carry those cans of stew around.

He pulled out the gun then, the one he’d been pretending not to finger the whole time.

“Give me what’s in your bag, bitch,” he snarled, his lips pulling back from his teeth.

Red calmly put the bowl in her lap to one side. “No.”

“Give it to me or I’ll shoot you,” he said, waving the gun in her general direction.

He thought he was being menacing, and it made her snort. He looked like a cartoon villain in a movie, a mangy excuse for a badass—the kind that threaten the hero when he walks through an alley and get thrashed for their trouble. She wasn’t dumb enough to think that he couldn’t hurt her, though. Even an idiot with a gun was dangerous.

“Are you laughing at me?” His face twisted in fury as he stepped closer.

He was coming around the side where she’d rested the pot, as she’d expected. He was afraid of the axe, though he didn’t want to acknowledge it, so he was giving the bloodied blade a wide berth. That was fine by Red.

“What’s the matter, bitch? Scared?” he cooed. He mistook her silence for fear, apparently.

She waited, patient as a fisherman on a summer’s day, until he was within arm’s length. Then she grabbed the pot handle and stood as fast as she could, using her real leg and her free arm for force to push upward and tapping her other leg down only for balance once she was on her feet.

The trouble with the prosthetic was that it didn’t spring—Red didn’t have a fancy blade that could perform feats of athleticism—but she’d figured out how to compensate using her other leg. She needed to prevent the coyote from killing her for her food.

Her sudden movement arrested him, his gaze flying to the axe that he’d expected her to grab. Red could have, she supposed, stayed right where she was on the ground and embedded the blade in his thigh, but that might have resulted in a protracted struggle and she didn’t want a struggle.

The goal was not to have a fancy movie fistfight that looked good from every angle. She wanted him down. She wanted him done. She wanted him unable to grab her.

Red flung the rest of the boiling stew in his face.

The intruder screamed, dropped his gun, and clawed at his skin. It blistered and bubbled, and she noticed she’d managed to hit one of his eyes. She didn’t want to think about how horrible that felt because it looked like something awful. Red forced down the gorge that threatened at the smell of his burning flesh. She grabbed up the axe then and swung it into his stomach.

All the soft organs under his shirt gave way—she felt them squishing beneath the pressure of the blade, and hot blood spurted over her hands and then there was an even worse smell: the smell of what was supposed to be inside your body coming out, and she did cough then, felt the little mouse bite of her dinner coming back up mixed in with bile. It stopped her throat and made her whole body heave.

But Red wasn’t about to let him get up again and come after her and so she pulled the axe straight across his torso before yanking it out. It made a squelching, sucking sound as it emerged. Red wasn’t accustomed to that sound yet. No matter how many times she used the axe it made her skin crawl.

The man (for that was all he was after all, just a man, not a coyote, not a hunter) fell toward her and she backed away as quick as she could, no fancy acrobatics involved. Red was not some movie superhero any more than the man was a movie villain. She was just a woman trying not to get killed in a world that didn’t look anything like the one she’d grown up in, the one that had been perfectly sane and normal and boring until three months ago.

The man fell to the ground, and the blood seeped from the wound in his stomach. He didn’t make any noise or twitch or anything dramatic like that, because he’d likely passed out once his brain was overwhelmed by the pain from his burn and the pain from the axe. He might live—unlikely, Red thought, but he might. He might die, and she was sorry not that she’d done it but that she had to do it.

Red didn’t like to think of herself as a killer, but she wasn’t about to let herself get eaten up just because she was a woman alone in the woods.

She gathered all of her things from the site, slung her pack on her back, doused the fire she’d so carefully built. She cleaned her axe as best she could with a cloth, then covered the blade and put the handle in a Velcro loop on her pants.

The gun her attacker had dropped gleamed in the faint starlight, and she reluctantly picked it up. If she left it behind, someone else might find it and that person might cause her trouble later. After all, she hadn’t killed all three of the people she’d encountered earlier.

Red didn’t know anything about guns except that she didn’t like them. Her father had liked to watch crime television shows, and on those programs everyone seemed to know how to click the safety on and off and load the gun even if they’d never touched a weapon before. Red didn’t have the faintest idea how to do any of that and she didn’t want to fool with a gun in the dark. That seemed like an excellent way to shoot herself in the only organic foot she had remaining. Shoving the weapon (which she assumed was ready to fire, based on the way that fellow had been waving it around) in her pack or waistband seemed just as stupid.

Red despised holding the gun, despised everything about it, hated how cold and hateful it felt in her hand. But she held on to it, the barrel pointed away from her and her finger off the trigger, as she walked away from the place where she’d hoped to camp for the night, the place where she’d wanted to rest for a little while because her half-a-leg was weary from the quick march that morning, and now that she was moving onward again she realized just how much she’d wanted to take off her prosthetic for a while.

She was very good about removing it periodically while she walked, and drying the stump, and putting cream on it so the limb wouldn’t chafe, but it was a relief to remove the contraption every night and just let her leg be.

The coyote (the man) had taken that relief from her, and now she was hungry (for she hadn’t eaten her stew) and angry (for she’d had to kill him and she really hadn’t wanted to) and resentful (for her leg ached and she was walking when she didn’t want to be walking and she was carrying his stupid hateful gun).

Close to dawn she heard the comforting rush of water, and she angled her path toward it. As she got closer to the noise Red’s progress slowed—running water attracted all sorts, including bears and other people. For the most part Red liked to avoid both if she could. Her experiences thus far had told her that one was as dangerous as the other.

She came across a handy clump of bushes to hide behind (after carefully examining them for poison ivy—she had quite enough problems without getting a rash all over her face or hands) and waited to see if there was any movement around.

The stream was about six or seven feet wide and running quickly, which meant it would be a good place to refill her water bottle. She knew well enough not to drink from standing water; she didn’t know why anyone would want to anyway as it was usually covered in green scum, but probably people got thirsty and desperate and that made them do foolish things. Well, Red had seen plenty of evidence of foolish behavior before the Crisis; it was only logical there would be just as much after.

There was a filter on the bottle that supposedly kept out parasites and other things but that wasn’t really what worried her. There was always the chance of a body in water, a bloated infected thing that let its infection ripple out from it, searching for another host to feed its million billion trillion children.

She knew this wasn’t an entirely logical fear; the Cough that killed everyone was an airborne disease and airborne diseases didn’t usually swim in water, but the virus might have mutated. It was entirely possible that it mutated, and that mutation might mean that whatever had stopped her from catching it before wouldn’t protect her now.

This water was running swift, swift enough to reassure her, and she would have to take a chance with a possibly mutated virus. This was not a safe place to stop and build a fire and boil it and let it cool until it was safe to drink.

Red waited and watched for a while, just to be certain that nobody else was on the opposite bank waiting and watching. After a bit she felt her head nod forward and she jerked it back in that panicky way that you do when you realize you’re falling asleep and don’t want to. She widened her eyes, as if just the act of making them bigger would stave off sleep. She was tired, more tired than she’d realized, and being tired meant that she was vulnerable and that scared her, because nobody was going to keep her alive but her.

I’m being too cautious, she thought. There was nobody about for miles. The only movement she’d heard along her night-walk from the place where she’d killed the coyote (the man, he was a man, even if he looked like a coyote, even if he looked like something whose eyes shone out of the darkness above sharp teeth) had been the scattering of little things, chipmunks and squirrels and field mice.

She was the only person near the stream at this exact place. Yes, she needed to be careful but there was such a thing as being too careful—she’d never get anywhere at this rate. Her leg wouldn’t let her walk too fast and she knew that she could only make so many miles a day—the brain was willing but at some point her body would say, Hell, no, not another step, and that was that. Too much caution only exacerbated her slow crawl. It was safe enough to approach the water.

The bank was steep and anything steep is always awkward when you’ve only got one whole leg—it didn’t matter if she was going up or going down, although up was a little easier. Going down always felt like she might lose control at any second, because she felt the imbalance of her legs more acutely and when she thought too much about walking it seemed to make it more awkward.

Red slid the last couple of feet to the water and her real foot splashed in the stream and she cursed. Her hiking boots were waterproof, but her pants weren’t and the water seeped through and ran down her ankle and made the top of her sock wet.

She hated wet socks—ranked them in her top three least favorite things, right after black licorice (just the thought of that anise/fennel/whatever-the-hell-it-was flavor made her nose wrinkle) and people who stopped in the middle of the grocery aisle to fool with their phones when other people wanted to shop. Though she supposed that wasn’t really a problem anymore, and it was easy enough to avoid licorice.

The stream was deeper than it had appeared from her perch. Deep enough, she thought, to hide the presence of the hateful thing in her hand that she so badly wanted to be rid of. She tossed it in the center of the running water and heard the satisfying plop as it sank in. Red couldn’t see the gun from where she stood, and she hoped that it went straight down for a few feet, and that no one else would find it. Or if someone ever did it would be rusted and unusable.

She crouched in the mud, reaching out with her bottle to fill it from the current, not from the muddy eddies that swirled closer to the bank. Red gulped most of the first bottle straightaway—she hadn’t realized quite how thirsty she was until the first cool touch of liquid on her tongue. The scorched bit from the hot stew was still numb.

Red refilled the bottle twice more, guzzling water until it sloshed around in her stomach, and then stood—carefully, as the footing was not very sturdy this close to the water and it would be very tiresome to have to change her clothes since she only had one other pair of pants in her backpack.

Red needed to cross the stream, partly because she needed to continue heading north and partly because if that man who came to her fire hadn’t been a total liar there might be soldiers somewhere behind her. Soldiers sometimes had dogs with them, dogs to help sniff out the infected and the uninfected alike.

She was sure that a smart, well-trained dog would have no trouble following the smell of blood on her—no matter how careful she was, some of it always splashed on her pants. Dogs could help those soldiers catch up to her a lot faster, but crossing the water would make them lose her trail.

At least that was what always happened in the movies (a good deal of Red’s survival knowledge was culled from books and movies)—the hunted would swim across a river and then all the barking, baying hounds following that hunted thing would run up to the edge of the water and bark and turn in circles and the people with them would shake their head and say the dogs had lost the trail at the water.

Red would not be a hunted thing. She didn’t want to be scooped up in anyone’s butterfly net and pinned to a board. She was going to her grandmother’s house, because she was the only person left in her family that could do so. The last time she’d talked to her grandmother (before all the telephone service, wired or unwired, stopped working), the old lady had told Red and the rest of her family to come so they could stay safe in the woods, together.

That was six weeks before, and many things had happened since then. And every day Red imagined Grandma peeking through the curtains of her cabin in the woods, watching for her family to emerge out of the trees and into the clearing.

Whenever Red thought about this her eyes would tear up, because though she could go on alone it was very tiring to do so and all she wanted more than anything was to have someone to lean into. Grandma was the nicest person to lean into, because she was soft and round and smelled like whatever she’d just been cooking (and she was almost always cooking).

It was impractical to walk along the bank—the mud sucked at her shoes and made walking more of a chore than usual. She hated the idea of staying along the higher part of the bank, though, even though the footing was better. There was hardly any tree cover and she would be dangerously exposed. The way the land rose away from the stream hid her from view unless someone got close to the water.

Of course, she reflected that it also meant that any approaching person was also hidden from her. Besides, it would be easier to get away quickly if necessary from the higher part of the bank.

Weren’t you just saying not to be overly cautious? She needed to stop weighing and measuring every decision like her life depended on it.

(It might, though)

Well, that was the trouble, Red reflected. Every choice could be the difference between living and dying, and it had been that way for long enough now that she’d almost forgotten what it was like to make silly choices—to watch a horror movie instead of a samurai movie, to have ice cream for dessert instead of a candy bar, to read a book instead of vacuum the floor. She almost wished for a dirty floor to vacuum just then. At least it would mean that nothing had changed.

Red went up on the high part of the bank and tried not to rub the back of her neck. It felt like someone was watching her, but whenever she glanced back there was nobody and she knew damned well that it was her imagination but she couldn’t stop it.

Sometimes the more you tried not to think about a thing, the more you did, and Red had a case of what Grandma called “the heebie-jeebies.” Once you got the heebie-jeebies it was hard to shake them loose. If you kept thinking there was a spider on your neck you’d keep brushing at your collar even though you damn well knew no arachnid was crawling on your spine. Or you’d keep looking behind you even when there was no evidence that you were being followed.

After she’d walked about half a mile she came to a little footbridge, one of those kinds that swung side-to-side when you walked on them—just rope and some panels tacked on at the bottom. She surveyed it doubtfully. She’d never liked these kinds of bridges even before she lost the bottom half of her left leg. There were always swinging bridges of this sort on playgrounds so certain kids could terrorize most of the others by herding them on and making the bridge shake.

Still, the bridge was the first chance of a dry crossing she’d seen, and she reasoned that at least she would be able to hang on to the ropes if she felt less-than-sturdy. If she crossed on rocks or some such thing there wouldn’t be any ropes to grab onto if she felt herself falling.

She slid her real foot onto the bridge and felt the whole thing wobble as soon as her weight pressed in.

“Screw that,” she said, her heart pounding as she stepped back. “Besides, what happened to shaking off the dogs? You’ve got to go in the water if you want to do that.”

Red tried not to talk to herself because it reminded her too much that she was alone but sometimes words just fell out of her mouth, like they were trying to remind her that she could still speak.

She shrugged her pack up and down to shift the weight a little bit and decided to go on until she could find a shallow place to cross.

As she walked she started to get the so-tired-she-was-delirious feeling, the feeling that everything ached (but especially her stump, she really did need to rest it for a while) and her eyes were going to wink shut of their own volition.

Soon she would fall down on her face and pass out. It was inevitable—she was pushing herself too hard and too far and she just needed to cross the damned stream and find somewhere she could rest for a while and stop thinking, because the more she thought, the more she worried, the more she drove herself into crazy circles trying to anticipate every possible bad thing that could happen and avoid it.

“Just someplace to put my head down for a while, that’s all I need,” she said as she sat on the bank and pulled off her sock and shoe from her real foot and rolled up both pant legs, exposing the shiny metal tube on the left side.

The water was cold, really cold, and the shock of it startled her. The stream was deeper than it looked, even though she’d found a place where it seemed shallow. It came up to the middle of her calf instead of just above her ankle as she thought it would. Red slogged across, mindful of rocks that could trip and mud that could trap and any other thing that might go wrong.

When she reached the other side she felt much more awake because that little bit of cold water on her bare skin made her shiver all over. She hurriedly dried her foot and leg with a small towel from her pack, noting that the sun was almost exactly overhead now.

There hadn’t been any sight or sound of people or animals since she’d encountered that man the night before, but she hurried away from the stream, grateful for the thicker cover of the woods on this side.

Red did not want to camp so close to the water. She continued on for another half hour or so, keeping a close eye on the shadows around her and listening for the sound of anybody else hiding in the trees.

Then it just appeared before her, almost like a hallucination summoned by her exhausted brain. A cabin. A cabin all by its lonesome, in a clearing in the woods.

For one brief moment she thought she’d somehow gotten to her grandmother’s house already, that she’d walked farther than she realized in the night. Then she shook her head and recognized that this building was about a quarter of the size of her grandmother’s—Grandma had a two-story with four rooms on the ground floor and a loft bedroom above, built with love and care by Red’s grandfather, who always went by Papa.

This was more like a hunting shack, a one-room affair with rough-hewn logs and a small metal chimney. There were beige-colored curtains over the one window she could see, but there didn’t appear to be any signs of life.

That doesn’t mean anything. Someone could be asleep inside, someone with a shotgun next to his bed who’ll blow your stupid head off if you knock on the door. And anyway in the movies people always get stuck in some cabin in the middle of nowhere and it seems like there’s nobody around but actually there is a serial killer lurking nearby who can just fade into the trees and wait for someone to walk into his trap.

(Red, don’t go thinking stupid thoughts. If there was ever a serial killer here he’s probably dead from the Cough just like everyone else.)

That last bit sounded like her mama’s voice, her very practical mama.

But there might be someone in there, there really might.

She found her feet moving toward the cabin anyway, even though her brain was saying, No no no too risky. Her legs had mutinied, taken the rest of her hostage, because her heart had seen that little cabin—rough and no doubt filthy it would be—and longed for it. She longed to sleep somewhere inside, under a roof instead of the open air or the thin nylon of her tiny tent.

She longed for the security of a boundary on all sides, of feeling tucked in and cozy and knowing that nobody could sneak up on her if the door was shut and locked. That was something she’d taken for granted before, before Everything Happened—the feeling of being indoors, of being safe.

Red couldn’t let go of her caution, though—couldn’t just walk right up to the door and act like she belonged there (because there might be a guy there with a shotgun, there really might, or a killer with a machete). She crept toward the one window as quietly as she could, which was not very quietly because there were dry dead leaves all around the clearing that seemed as loud as firecrackers in the still air.

She peered into the interior through the little crack in the curtains but couldn’t see anything except the handle of an old-fashioned metal percolator sitting on a table under the window. The rest of the cabin was too dark. So she looked closer at that percolator handle, because it was the only clue she had.

The dust was thick on the top curve of the handle, too thick to have been used by anyone recently. Which meant there probably wasn’t anyone inside. Probably.

She walked all around the cabin, looking for footprints

(like you’re some kind of tracker, ha, what do you even think you’re looking for?)

because even if she wasn’t some kind of tracker she could recognize a fresh print in the dirt if she saw one and she didn’t see any around the cabin or by the door.

Having done the only safety check she could do, Red approached the front door and tried the handle.

It was locked.

She laughed out loud then, and the laugh sounded a little crazy because she was exhausted and hungry and she’d been so concerned about a maniac with a gun that she hadn’t thought of the possibility of the owner locking the door when he left his cabin at the end of last season.

And then she cried a little too, and when she heard herself doing that loony laugh-cry thing she knew she was getting hysterical and she said, “Enough.”

Work the problem, Red.

That was her dad’s voice, not hers—it was the thing he always said when she was stuck and frustrated. For a long time it annoyed her until she realized that he was telling her to take a breath, to step back, to consider all the options one by one. It was a marvel of brevity, actually, to say all of that with just four words.

The window was far too small to climb through, even if she could break the glass—and she didn’t want to, for if she managed to get inside she wanted the window closed.

She peered all around the door, because sometimes folk kept emergency keys around in hidden places just in case. She got up on her tiptoes (and nearly fell over for her trouble, because she was balancing on just one leg) and felt around the frame at the top of the door and found nothing except a big old splinter that embedded itself in the middle knuckle of her ring finger and made her shout.

The splinter would have been nothing in the Old Days (she’d come to think of the time before everything changed this way, and just like the Crisis it was always capitalized in her head)—she would have yanked it out and maybe slapped a bandage on the wound and that would have been that. But now an infection was so much more than an infection. Not only was every open wound a potential pathway for the murderous, possibly morphing disease that had killed so many people, but without antibiotics any cut or scrape might be a killer.

Red did, as a matter of fact, have some antibiotics in her bag—a fortuitous discovery made early on in her journey—but she didn’t want to use them unless she needed them. Those pills were more valuable than diamonds.

So she sat down in the dead leaves in front of the door and pulled her first-aid kit out of her pack. She carefully scrubbed her hands with an antibacterial wipe and then did the same for the tips of the plastic tweezers in the kit. The splinter came out easily, and she cleaned and bandaged the bloody hole that remained and then stuffed her kit back in her pack.

Red sighed then, not wanting to stand up. She was just so tired. She’d never known a person could be so tired before everything had happened but it was like a cloak on her all the time now, a cloak made of tired that pressed down on her shoulders and made her neck droop.

And because she was sitting down in the dead leaves she saw something she hadn’t seen before—the little knot in one of the logs, just about a foot off the ground. Red took out her flashlight (solar plus a hand crank, so she wouldn’t have to hunt for batteries, and one of her better ideas) and peeked inside the knot.

Four or five inches back, far enough that someone couldn’t find it by accident, something bronze gleamed.

Red grabbed the key and heaved herself to her feet. As she unlocked the door she felt a surge of joy.

Inside. I can sleep inside.

The dust was thick enough to get stirred up by her feet and make her cough. She fought the impulse to slam the door shut behind her (safe, she could be safe at least for this one night) and instead found a broom hanging from the back of the door and swept out all the dust and opened the curtains to let in some light.

There were two cots folded in the corner and a small wooden table with two chairs and the percolator she’d seen from the window.

The chairs had metal frames and yellow vinyl seats and looked like something the owner had found in someone’s garbage, but they were sturdy enough and Red supposed that anything would do if you just needed someplace to sit and eat before heading out into the woods for the day.

Next to the window were three wooden shelves, and on the bottom one were plates and cups and bowls made of metal and painted blue with white speckles. There was an open mason jar with utensils sticking out of it and next to it a cast-iron frying pan and a big pot. There was even a camp stove and some cans of propane, which meant that she wouldn’t have to go outside to build a fire.

But the shelves above were full of real treasure. Canned soups—lots of them, in lots of varieties, and just-add-water meals that were vacuum-sealed. There were packages of dried pasta and two jars of tomato sauce and even a sealed package of crunchy bread sticks, though Red figured these were probably stale. On the floor below the shelves was the best find of all—several sealed gallon bottles of water.

The first thing that disappears from stores when there’s anything resembling an emergency is bottled water. People in America live in terror of going without water, a resource that is—or was—ridiculously abundant in that country. As soon as it became clear that the disease was spreading faster than anyone realized and that folks were going to have to dig in or evacuate or whatever, the cases of bottled water flew out of grocery stores like they’d sprouted wings.

On the news there had been the inevitable footage of people fighting like animals over the last few cases of water in a grocery store. Whenever Red saw this kind of thing she always wondered why the person filming hadn’t tried to help or intervene instead of taking video of his fellow man at his worst.

Red could pack the dried meals in her bag when she left the next day and they wouldn’t add too much weight, and while she was here she could eat pasta with tomato sauce. It seemed like an unbelievable luxury, the idea of spaghetti and tomato sauce from a jar. There was even a table to sit at, instead of crouching over a plate on the ground.

But first she unfolded one of the cots. It smelled a little musty, but what was that if she could sleep raised above the ground—the ground that seemed to seep through the bottom of a tent and into the warm lining of a sleeping bag and make everything sort of damp no matter what precautions she’d taken against it?

She closed the door and locked it—there was a lock on the knob and a bolt lock just above her eye level and the sound of the bolt clicking home was beautiful music. All around her she felt the comforting press of the walls keeping her in, and she heard no noises of little animals scuttling along or birds twittering or wind in the trees. It was silent, and she was safe.

But what if someone comes along while you’re sleeping?

No, she was not going to do that again, not going to go around in circles and make herself completely insane. She was going to take off her leg—and she did, clicking the button at her ankle and pulling the artificial joint out of the socket with a happy sigh.

Red unrolled the sock that she wore over her stump and cleaned and dried it and examined her skin for blisters or redness. The fear, always the fear with a stump was that you would Do Something that would result in having to take more of the leg off.

This was the constant threat that had hung over her in the early days after they’d amputated, and she never lost the free-floating anxiety that somehow the remaining part of the leg would get infected, that the infection would get into the bone, that there would be gangrene or necrosis and then the saw would come out and she’d lose a little bit more, and then a little bit more until there was nothing left of her leg at all.

Of course she could go on if that happened—she’d only been eight when her leg was amputated, and had now spent more of her life with a prosthetic than without. There was very little she couldn’t do, and she didn’t really think about it as a limitation (even if a lot of other people who looked at her with sympathetic gazes did).

But you never really got over that loss, she thought dreamily as she snuggled into her sleeping bag. You never stopped feeling the lack of the thing that was gone. Just like all the days she’d walked alone in the woods, and every time she’d turned to say something to her brother or her father or her mother, and found that they weren’t there, even if she felt they were, that they ought to be.

CHAPTER 2

All Our Yesterdays

BEFORE

They had to get to Grandma’s house. It had been decided, and Red was ready to leave, but no one else seemed to be and it was certain that she was the only one who felt any sense of urgency about it.

Adam had dithered around all morning, trying to fit everything he couldn’t bear to leave behind in his pack, and their parents weren’t doing a very good job of hurrying him along.

Red’s brother was only home at all because his university term hadn’t begun when the outbreak started and as a precaution they’d told all the students to stay home until the danger passed, thinking (correctly in Red’s opinion) that a dormitory was the perfect petri dish for spreading disease—all those not-very-hygienic students crammed together in a rabbit warren of shared spaces.

But the danger never had passed. It had only gotten worse, despite quarantines and precautions and the supposed late-night efforts of desperate doctors to find and manufacture a vaccine to stop the nightmare that was rolling across the country.

Her parents, too, kept sighing over the things they had to leave behind—the photographs and the books and her mother’s wedding dress and the bronzed baby shoes and other things Red kept telling them didn’t matter, it was their lives that mattered, but nobody would listen to her. That’s what happens when you’re the baby of the family, even if you’re a twenty-year-old baby.

Red’s mother was already sick then, had started coughing the night before. That cough started off sounding oh-so-innocuous, like something was just stuck in her throat that she needed to get out, and she drank several cups of tea with honey and exchanged a thousand worried glances with Red’s father, because they both knew what it meant and didn’t want to say it out loud.

Parents, no matter what age they were or what age their children were, would always try to shield, to pretend nothing was wrong. But Red was no dummy and she knew what that cough meant, knew it meant they’d all been exposed and now they just had to wait and see if they would all catch it. Not everyone did. Some people seemed to be naturally immune.