18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

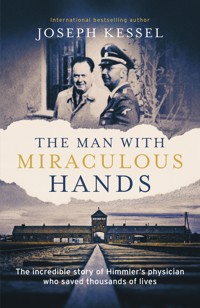

The incredible story of Heinrich Himmler's physician who saved thousands of lives. With a new introduction by bestselling author Norman Ohler, which addresses Kersten's flawed legacy. In 1938, before the outbreak of the Second World War, Dr Felix Kersten an avuncular Finnish physician was introduced to Heinrich Himmler, the chief architect of the Holocaust. Seemingly the only person who could cure Himmler of his crippling stomach cramps, Kersten worked on Himmler's vanity and gratitude Kersten to save the lives of thousands of people, and was celebrated across Europe, culminating in Joseph Kessel's 1961 bestseller, The Man with Miraculous Hands. And yet, Kersten's historical legacy is not flawless, and a new introduction by bestselling author Norman Ohler, deals with the historical legacy of Kersten's more exaggerated claims, and asks directly why a man who had done so much good would risk damaging that reputation. Soon to be a major motion picture starring Woody Harrelson, The Man with Miraculous Hands is an extraordinarily revealing portrayal of the deranged atmosphere in Himmler's court where paranoia and vicious rivalries reigned. Shedding a new light on the darkest days of the twentieth century, the story of Kersten's life gives us a new way of viewing the history of the Second World War, one that goes beyond the simple idea of heroes and villains.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 405

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Contents

Chronology

Foreword by Norman Ohler

Prologue

1 Dr Ko’s Pupil

2 A Happy Man

3 The Beast in His Den

4 The Battle Begins

5 Gestapo

6 A Nation to Save

7 Genocide

8 The Jehovah’s Witnesses

9 Hitler’s Disease

10 The Great Plan

11 The Ambush

12 In the Name of Humanity

13 Mazur, the Jew

Appendix

Index

Chronology

30 January 1933: Hitler comes to power

30 June 1934: Hitler has Roehm, commander in chief of the SA, assassinated by Himmler and the SS

13 March 1938: The annexation of Austria

29 September 1938: At Munich, the heads of the English and French governments, Chamberlain and Daladier, surrender part of Czechoslovakia to Hitler

15 March 1939: Complete annexation of Czechoslovakia

1 September 1939: Hitler attacks Poland

3 September 1939: England and France declare war on Germany

10 May 1940: Invasion of Belgium and Holland

22 June 1940: Defeat of France. Marshal Pétain signs the armistice

6 April 1941: Invasion of Yugoslavia

22 June 1941: Hitler attacks Russia

11 December 1941: US declares war on Germany

August 1942: The German Army reaches Stalingrad

8 November 1942: Allied troops land in North Africa

31 January 1943: The Allies land in Sicily

10 July 1943: Germans surrender at Stalingrad

6 June 1944: Allies land in Normandy

29 April 1945: Hitler commits suicide

23 May 1945: Himmler commits suicide

Foreword

by Norman Ohler

The task of writing an introduction to a problematic book is not an easy one, but it is all the more rewarding for that. Even more so when dealing with the legacy of an individual whose actions during the Second World War can only be fully understood within the context of post-war history.

Hardly any book that I know of is more in need of reassessment than this one, since it touches on those events that we have collectively agreed are the most serious crimes that have ever occurred on this planet: the genocide of the Jews and the further inconceivable atrocities committed by the Nazi regime in the concentration camps and on the battlefields of Europe. Responsible for these murders, for the unspeakable suffering, are the many people who supported the Hitler state, who built it and ran it. But among the many there are outstanding perpetrators, and at their head, along with the dictator himself, is Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS. He is one of the main characters of this volume, a crucial part of which is set in his office and private rooms – relating intimate encounters that allegedly took place there and claiming to provide a unique insight into the personality of the Nazi mass murderer.

The protagonist who takes us inside the lion’s den is an equally real person and bears the name Felix Kersten, a Finnish ‘doctor of manual therapy’ whom many referred to as ‘Himmler’s masseur’, since that was the job he performed for the Reichsführer SS. Previously, Kersten had mainly treated wealthy, often aristocratic clients in Scandinavia and the Netherlands (where even the extended royal family were among his patients). But he was introduced to Himmler and the false glamour of the Third Reich through an influential friend – and after his first treatment for horrific intestinal pain, Himmler requested Kersten’s services again and again.

Kersten willingly accepted this recruitment and his consequent proximity to the dark power that dominated Europe at the time. He acquired an estate north of Berlin and even had prisoners from a nearby concentration camp serve him there – the sort of terrible practice that was more common in those years of fascism; comparable, for example, to Theodor Morell, Hitler’s personal physician, who also profited from the Nazi system, hiring forced labourers in his pharmaceutical company.

But there is an immediate significant difference between these two doctors. Morell, who joined the Nazi party in 1933 and was with Hitler in his bunker until the final days of the war, on the one hand, gives a credible and thoroughly fascinating picture of the dictator by keeping meticulous notes on medications and Hitler’s state of mind as well as his physical condition. Morell does so without ever looking too much at himself. He is content to step back, disappear in the shadow of his mighty ‘Patient A’. He keeps Hitler functioning, nothing more, nothing less. Kersten, who never joined the Nazi Party, however, is a completely different story.

In his memoirs, on which Joseph Kessel based this book, Kersten insisted that he had performed his duties on Himmler only in order to carry out a series of heroic deeds. In no way had he profiteered from his position, he said; rather, he had only played his part to push his own agenda and avert as much disaster as possible. And he declared that he had achieved exactly this with the most astounding success: he had saved thousands of people from the death camps through his massage work, extracting concessions from Himmler at the magic moment when his pain disappeared. Kersten claimed that he had known exactly those vertebrae in Himmler’s spine where he could employ skilful movements to manipulate the Reichsfürer’s will; exactly the spot in Himmler’s stomach, plagued by flatulence, where he could provide such relief through expert squeezing that his patient obeyed every humanistic wish from his lips. Kersten simply increased the energy flow of his patient, eased the pain, and the head of the SS would relax, even open his heart. Kersten maintained that if Himmler had rejected his demands, he would have refused to continue his treatment. ‘If he asks me to keep him functionable,’ said Kersten about Himmler in his memoir, ‘he must also listen to my instructions.’

Kersten even went so far as to claim that he had succeeded in saving the entire population of the Netherlands, a country he loved dearly, from being deported to eastern Poland. The Dutch government appointed a commission of historians to examine the facts, chaired by the head of the Netherlands Institute for War Documentation, Nicolaas Posthumus. He found no fault with Kersten’s account, since his ‘very accurate description shows so many details that one cannot imagine a fiction, unless one would consider Kersten to be an extraordinary fantasist’. On the contrary, Posthumus, who was a friend of Kersten’s, described the Finnish healer as a ‘saviour of mankind and benefactor of the highest rank: his work deserves our adoration.’ As a result, in 1950, the Dutch king awarded Kersten one of the country’s highest honours, making him a Grand Officer of the Order of Orange-Nassau, bestowed on him by Prince Bernhard personally, and the Dutch government nominated him for the Nobel Peace Prize four times. The respected British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper also commented on Kersten’s memoirs, branding them a ‘gigantic achievement’ and a ‘shining example for human behaviour’, although his opinion of Kersten notably cooled in the years that followed.

There is no question that Kersten did do some good. For example, he played an important role in the Red Cross action to bring released Belgian, French and Dutch concentration prisoners to Sweden shortly before the end of the war, which saved the lives of up to 60,000 prisoners. It is difficult to think that he could have done this without having achieved a significant role of influence within the Nazi High Command in its final days. However, doubts have been cast on Kersten’s more extraordinary claims. It is certainly the case that in the spring of 1941 Hitler had planned to punish the Dutch who had rebelled against the Nazi occupation and transform the country into an SS colony. But history tells us that these plans were never drawn up, let alone called off. All of which means that Kersten’s account of overhearing this monstrous plan in the SS canteen in Berlin must be read as a fabrication, along with his assertion that he saved the entire Dutch population.

Nevertheless, at the time Kersten was widely celebrated. In France, people pounced on Kersten’s account. And perhaps it is telling that a nation that had wrestled with its own history of Nazi collaboration was so keen to embrace the story: here was a person who had clearly benefited from a life under the Nazi regime but had also used his position for the greater good. Perhaps, too, this reaction speaks to the idea that during such monumentally horrific episodes in human history there are no clear-cut heroes or villains – the line between collaborator and survivor is very thin.

Certainly, Joseph Kessel seemed to understand this when he wrote Les mains du miracle in 1961. Kessel, an adventurer, journalist and writer who also penned the novel Belle de jour, initially thought Felix Kersten’s story was implausible. But he found himself convinced, relying on the expertise of the Dutch Historical Commission and that of Trevor-Roper, who contributed the foreword to the original edition. Since it was clear to Kessel, however, that it was problematic to rely solely on Kersten’s recollection of how events had unfolded, he called his text a hybrid of fact and fiction that leaves open to interpretation whether what we read here actually happened as described. He did not conduct any independent research himself.

What we can now ask, which perhaps Kessel was unable to at a time that was so much closer to the events in question, is why did Kersten, who unarguably did some tremendously brave and morally good deeds, choose to exaggerate his claims? Why risk undermining his public standing?

What Kessel’s book and the historical legacy of Kersten’s story provide us with is a revealing portrayal of the deranged atmosphere in Himmler’s court where paranoia and vicious rivalries reigned, and where a man like Kersten could thrive amid a group of people who had all lost their grasp on reality. Kersten put it this way: ‘In the course of my practice I have found over and over that one gains the trust of men in leading positions that might seem exaggerated to outsiders. Because such leaders are always surrounded by self-interested people, they are systematically put on the defensive. But they can safely relax when they are treated by doctors who are used to seeing them in a vulnerable state.’

And perhaps this is where the value of Kessel’s book lies for modern readers. It takes us into the mind of a man who found himself both a survivor and a collaborator at the same time. As he watched the Third Reich, which he had served directly or indirectly, fall apart, he had to justify his connection to Himmler, to distance himself from the Nazi butcher. However, rather than elevating himself above the atrocities that he knew Himmler and his inner circle had carried out, his outlandish inventions only succeeded in clouding his legacy.

The publication of this edition of The Man with Miraculous Hands, in the UK for the first time, coincides with the announcement that the actor Woody Harrelson is set to portray the role of the Finnish masseur on screen. Variety wrote of the book in question: ‘The Man with Miraculous Hands depicts Kersten’s remarkable true story as the physician whose therapies helped to relieve Himmler’s debilitating abdominal pain, thereby giving him extraordinary influence over one of the main architects of the Holocaust. With clever manipulations, and a flair for dangerous negotiation with his monstrous patient, Kersten was able to ultimately save thousands of lives from the concentration camps and outlive his captor.’ Variety describes the film, currently in the planning stages, as a ‘psychological thriller’, which raises the question: Are the film makers aiming for the real thrill here, laying bare the torn soul of their principal star, who felt the need to re-invent his life story so he could cope with the guilt of having served the evil Nazi ogre? For this film to be truly authentic it will need to acknowledge the re-evaluation of Kersten’s character, and the chaotic turns of his moral compass that led him to inflate his achievements to such an extraordinary degree. It must reflect what The Man with Miraculous Hands really is – an unusual view into the cultural apparatus of Nazi high command, a complex record of the 1940s and the post-war period.

If one thing is for sure it is that Kersten’s story is currently making a comeback, not because he is an undisputed hero but because his character symbolises a new way of viewing the history of the Second World War, one that goes beyond the angel-devil meme. Maybe there are no heroes in wartime. Only collaborators and survivors.

Prologue

Himmler committed suicide near Bremen in May 1945, during that spring when a ravaged, tormented Europe at last found deliverance.

If one only counts years, that time is still not so distant from us. But so many and such momentous things have happened since, that already it seems very far away. Already an entire generation has sprung up, a generation for whom those miserable days are nothing but vague and confused memories. And to tell the truth, it is even becoming difficult for those who underwent the full experience of the war and the occupation to recall, without considerable mental effort, quite the extent of the terrible power which Himmler once had at his disposal.

Let us make that effort . . .

The German Army occupied France, Belgium, Holland, Norway, Denmark, Yugoslavia, Poland and half of European Russia. And in these countries (not counting Germany itself, Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia) Himmler had absolute authority over the Gestapo, the SS, the concentration camps and even the diet of the captured peoples.

He had his police force and his personal army, his spy and counterspy services, his tentacle-like prison system, his organisations devoted to starvation, his immense private hunting and burial grounds. It was his job to watch over, round up, silence, arrest, torture and put to death millions and millions of human beings. From the Arctic Ocean to the Mediterranean, from the Atlantic to the Volga and the Caucasus, all were at his mercy.

Himmler was a state within a state: a state of informing, inquisition, Gehenna, of death endlessly multiplied.

Only one man was higher than he: Adolf Hitler. From him Himmler accepted the lowest, most loathsome, most perverse tasks with a sort of blind, joyous devotion. For he worshipped, adored Hitler beyond all measure. It was his only passion.

Beyond this, there scarcely existed in the dull, mean, dogmatic and incredibly methodical schoolmaster a lively feeling, a burning passion, a human weakness. For him it was enough to be the unchallenged expert in mass extermination, the greatest manufacturer of tortures and multiple death that history has ever known.

But a man came along who, during those awful years between 1940 and 1945, week by week, month by month, found a way of saving people from the unfeeling and fanatical butcher. This man so worked on Himmler the all-powerful, Himmler the pitiless, that entire populations escaped the terror of deportation. He prevented the crematory ovens from receiving their full quota of corpses. And alone, unarmed, half prisoner, this man forced Himmler to deceive Adolf Hitler, to dupe his master, to betray his god.

I knew nothing of this story until a few months ago. It was Henri Tones who first sketched the main lines for me. He added that a friend of his, Mr Jean Louviche, knew Kersten well and suggested that we meet him. Of course, I agreed.

But I will confess that despite the assurances of the greatest lawyer of the day and of a distinguished, internationally known jurist, the story still left me more than sceptical. It was downright incredible.

It seemed even more so when I found myself in the presence of a man who was very stout and mild-mannered, with kind eyes and the sensual mouth of one who loves the good things of life: in short, Dr Felix Kersten.

‘Come now!’ I said to myself. ‘This man against Himmler?’ And yet, little by little, I don’t know how or why, I sensed that from this calm, good-natured exterior, there emanated a hidden and profound power which was steadying, reassuring. I noted that his glance, though kindly, was also extraordinarily level and shrewd. And the mouth, however sensual, also had sensitivity and vigour.

Yes, this man possessed a strange inner strength. But even so, to have moulded Himmler like a lump of soft clay? I looked at Kersten’s hands. I had been told that it was their skill which explained the miracle. The doctor usually let them rest, the fingers interlaced, upon the curve of his stomach. They were large, short, plump and heavy. Even in repose they seemed to have a life of their own, an assurance, a direction.

My doubts were still there but they were weaker. Jean Louviche then took me to another room in his apartment, where there were tables and chairs loaded with documents, newspaper clippings, reports and photostats.

‘Here are the records,’ he said. ‘In German, Swedish, Dutch and English.’

I recoiled from this mass of paper.

‘To be sure, I have selected the shortest and most critical ones,’ said Louviche, pointing to a separate pile.

In it, there was a statement by Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands, every word of which was glowing, almost immoderate, praise listing the reasons why the Grand Cross of the Order of Orange-Nassau, the highest decoration of the Netherlands, had been bestowed on Dr Kersten.

There were photographic copies of letters addressed to Kersten by Himmler, granting him the human lives which the doctor had requested. There was the preface to Kersten’s Memoirs, written in English by H. R. Trevor-Roper, professor of contemporary history at Oxford and one of the greatest authorities of the British Secret Service on German affairs during the war. Mr Trevor-Roper said, in part:

There is no man whose story seems at first glance as unbelievable as his. But on the other hand, there is no man whose story has been subjected to such minute investigation. It has been weighed by scholars, jurists, and even by political opponents, and has triumphed over all these tests.

When I returned to the living room, I felt a little dizzy. The thing was true, then. It had been proved, undeniably: this large, good-natured doctor, who looked like a cross between a Flemish burgomaster and a Buddha of the West, had dominated Himmler to the extent of saving hundreds of thousands of human lives. But why? And how? By what incredible miracle? Now a boundless curiosity had replaced my disbelief.

Little by little, detail by detail, memory after memory, I managed to satisfy my curiosity. I spent hours with Kersten, asking questions and listening to his answers.

In spite of the incontestable proofs which I had seen with my own eyes, there were certain parts of the story that I still refused to accept. Such and such an incident could not be true; it was simply impossible. My doubts neither surprised nor upset Kersten; he must have been used to them. He would simply pull out, with a half-smile, a letter, a paper, a testimonial, a photostat. And I would have to swallow that incident along with the rest.

1

Dr Ko’s Pupil

The great flood which ravaged Holland around the year 1400 swept away the workshops and factories where the Kerstens, a rich bourgeois family, had been making fine Flemish linen since the Middle Ages. After this catastrophe, they established themselves at Gottingen, in western Germany, and taking up their métier once more, regained their fortune. When Charles V visited the city in 1544, Andreas Kersten was a member of the municipal council, and to reward his achievements the emperor, without actually raising him to the rank of the nobility, gave him a coat of arms: two beams surmounted by a knight’s helmet and sprinkled with fleurs-de-lis.

The family continued to prosper at Gottingen for 150 more years. Then came a fire which ruined everything beyond repair.

The sixteenth century ended. Colonies were needed in the frontiers of Brandenburg. Margrave Johann Sigismund, the sovereign, granted a hundred hectares to the Kersten family. They worked it as peasants and farmers for two hundred years.

Brandenburg was no more than a province of the German Empire, and the nineteenth century was nearing its close when Ferdinand Kersten was killed in the prime of life by a mad bull, on the land which the margrave had given to his ancestors from Gottingen.

His widow, who was left with few resources and a large family, sold the farm and settled in the small neighbouring town, where she thought it would be easier for her to bring up her children.

Her younger son was raised to be a farmer, but he no longer had any land of his own. He looked for work and was offered a job as an administrator in the Baltic countries, which were part of tsarist Russia. He yielded to the destiny which seemed to be pushing his family further and further east.

The estate of Lunia, in Liflande, was immense. It belonged to Baron Nolke. The clan of which he was a member no longer exists, but it was quite large at that time in eastern and central Europe. The possessors of vast lands that were almost provinces in themselves, the Magnats, the Barines, lazy and pleasure-loving lords, left their property in the hands of stewards and went off to foreign countries, where they spent enormous sums of money.

Frederic Kersten was a man of great integrity, and so healthy that he was to reach the age of ninety-one without having known a day’s illness. This honesty and vigour he placed entirely in the service of his passionate love of farming. He might have gone on supervising the estate indefinitely in his master’s absence. However, during his frequent visits to Yurev, the principal town of the region, he met a Miss Olga Stubing, the postmaster’s daughter, fell in love with her, won her and married her. He left Baron Nolke’s employ in order to improve the property of his wife and father-in-law, who had a little piece of land outside Yurev and three houses surrounded with gardens in the same town.

Frederic Kersten and Olga Stubing were very happy.

The young wife was a very kind person. Almost every day she invited poor children into her home and fed and cared for them. Needy families came to her for help in times of trouble. Moreover, throughout the region she had the reputation of being able to cure fractures, rheumatism, neuralgia and stomach-ache by simple massage, and much more effectively than the doctors. When anyone remarked at this skill, which was not the result of study, she would reply humbly, ‘It’s very simple, I get it from my mother.’

One September morning in the year 1898, Olga Kersten gave birth to a son. He had a distinguished godfather: the French ambassador to Saint Petersburg. This diplomat, who had a passion for gardening, had become a close friend of agriculturist Frederic Kersten during the latter’s rather frequent trips to the capital on business and in connection with his farm. The president of the French Republic at the time was Félix Faure. In his honour, the ambassador-godfather chose for his godson the name of Felix.

From his first years the baby was surrounded only by kindness, simplicity, honesty and good sense. To the steady and unassuming virtues of old Germany were added the warmth and hospitality of a Russian home.

The town where the little boy grew up had all the charm of an old engraving. The houses were made of wood, constructed with large, visible beams, except for the main street, which was called Nicolaievskaia from the name of the tsar in power. There the buildings had stone façades. On Sundays, carriages harnessed with splendid horses promenaded there: landaus and victorias in fine weather, fur-covered sleighs in winter. The River Emba passed through Yurev on its way to Lake Peipus. During the cold months there was skating on it, and the students in their military caps and tunics crowded around girls whose cheeks were rosy with the cold and who wore, from one end of Russia to the other, the same dresses and the same maroon aprons.

Yurev was the seat of the provincial government, and its governor, functionaries, magistrates and police officers, with their hospitality, their good nature and their venality, were just like the people one finds in Gogol, in The Inspector General or Dead Souls. And the merchants, with their bullnecks, their flowing beards, their squeaking boots and their private language, were right out of the plays of Ostrowski. And the peasants fell to their knees when they passed in front of the cathedral. And when there were holy processions, all holy Russia shone on the garments and icons of the orthodox clergy which led the grand religious parades.

The samovar hummed from early dawn far into the night. Families were enormous, holidays numerous; the house and the table were always open to visitors.

In this bygone world of carefree ease, of leisure and plenty, the life of a child, provided, naturally, that his family was in comfortable circumstances and that he was unaware of the horrible poverty of the people, was one of almost magical sweetness.

In the life of little Felix Kersten, the conspicuous events were the charity balls at which his mother sang in that delicious soprano voice and with that gift for music which had earned her the nickname ‘the nightingale of Liflande’, while he secretly gorged himself with sweets. Then there were the holidays which he spent beside the sea, at Terioki, in Finland. There were the birthday presents, the Christmas presents, the Easter presents . . .

However, his happiness was marred by his poor success at school. It was not ability that was lacking, but attention, application. His teachers said of him that he would never do anything serious. He was forgetful, dreamy and inordinately fond of eating.

His father, tireless worker that he was, could not accept these defeats. He put them down to a home atmosphere that was too soft and permissive. When the boy was seven years old, he was sent to a boarding school a hundred kilometres from Yurev. He stayed there five years, without much improvement. Then he went to study at Riga, the great city in the Baltic, known for the rigour and excellence of its courses and teachers. There, with considerable effort, Felix Kersten succeeded in finishing his secondary school studies.

At the beginning of the year 1914, his father sent him to Germany to enrol in the famous school of agriculture at Guenefeld in Schleswig-Holstein.

It was there that, six months later, the First World War took Felix Kersten by surprise. He found himself abruptly cut off from Russia and his family. As it turned out, he did not have much time to lament his situation. The tsarist government did not have the slightest confidence in the large German-born population in the Baltic, at the borders of the empire, and so faithful to its origins. Thousands of families were deported to Siberia and Turkestan. Kersten’s parents were included in this exodus, which took them to the other end of Russia. A lost village in the desolate country around the Caspian Sea was assigned to them as their residence for the duration of the war.

Felix Kersten, separated from his family at the age of sixteen by warring armies and vast spaces, could no longer count on the help or support of anyone. It was for him the moment of truth.

Up to now, this great pleasure-loving boy, rather large and lazy, had understood nothing of his father’s stubborn devotion to work. The instinct of self-preservation now taught him this virtue overnight. From that time, it became part of the pattern of his life.

Two years later, at Guenefeld, he received his degree in agricultural engineering. After this, he was to spend a period of probation on an estate in Anhalt. The authorities made no difficulties over the proposed change of residence of a student born of a German father. The administration considered Felix Kersten a subject of Kaiser Wilhelm II. But such privileges had their attendant duties. In 1917, Felix Kersten had to join the army.

He was now a young man of ample proportions, a temperate and peaceful disposition, and great emotional stability. While he admired the German people for their capacity for work, their methodicalness, their culture and their music, he hated uniforms, Prussian militarism, the fanatical love of discipline, and chauvinism. Moreover, he still had a secret nostalgic fondness for the Russia of his childhood. It was contrary to his nature to have to fight against it, with an army and for a cause that he could not admire. In the end, he found a compromise.

Each of the great conflicts that have threatened to upset the structure of Europe have given to the little nations, occupied by giant empires, the hope and sometimes the means of winning their freedom. In the hope of doing so, they have always sided with whatever power threatened their overlords. Thus, in the First World War, the Czechs, who were being oppressed by Austria, fought alongside the Russians. By the same token, the Finns in Germany now formed a legion to throw off Russian domination. Felix Kersten enlisted with them.

Meanwhile, the Russian Revolution had broken out, and the tsarist army was no more. The Baltic countries had also taken up arms for their independence. A Finnish force was sent to aid the Estonians. Felix Kersten, who was now an officer, was with this force. He even got as far as Yurev, his native town which, now liberated, had taken its old name of Dorpat. In 1919 he was lucky enough to find his parents, repatriated from the shores of the Caspian Sea after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

His mother had lost neither her youthful spirit nor her goodness. His father, although he was almost seventy years old, was as robust and hardworking as ever. He had accepted the agrarian reform in favour of the peasants, which had been one of the first measures of the new Estonian government, with his customary philosophic resignation, although it deprived him of most of his wealth.

‘A piece of land is always too big for one pair of hands,’ he told his son with a smile as the latter left with his regiment, which was still driving back the Russian guard.

Felix Kersten had to spend the entire winter in the marshes, without shelter. He contracted a rheumatism which paralysed his legs, and was forced to leave on crutches for the military hospital at Helsinki.

While he was convalescing, Kersten thought about the future. He could stay in the Finnish Army; he belonged to the best regiment of the guard. But nothing about military life appealed to him. His agricultural training? He no longer had any land on which to apply it, and he had no desire to work for someone else.

After a great deal of thought, Kersten decided to become a surgeon. He confided his plan to the head doctor at the hospital, Major Ekman. The latter had taken a liking to the young officer with the nice manners and even temper who was so mature for his age.

‘Believe me, my boy,’ he said, ‘I am a surgeon myself and I can assure you that the training is very long and difficult, especially for a young man like yourself who is without resources and must earn his living right away.’

The old doctor took Kersten’s wrist and went on, ‘If I were you, I would try to devote myself to the study of massage.’

‘Massage! But why?’ demanded Kersten.

Major Ekman turned the wrist over, indicating the strong, plump palm and the broad, short fingers.

‘This hand,’ said the major, ‘is ideally suited to massage, not to surgery.’

‘Massage . . .’ repeated Kersten, half to himself. He was remembering how, when he was a child, the peasants and factory workers in the neighbourhood used to come to his mother to be cured by her agile fingers of sprains, wrenched muscles and even minor fractures. In fact, even his mother’s mother had had the same skill. He told the head doctor about it.

‘You see! It runs in the family,’ exclaimed Major Ekman. ‘Bring your crutches and follow me to the clinic; you will have your first lesson right now.’

From that day the masseurs who were associated with the hospital began to instruct Kersten. And before a month had passed, the soldiers preferred the second-lieutenant student to the professionals. As for Kersten, he discovered to his astonishment and joy that his hands possessed the power to restore to the suffering bodies of men their flexibility, repose and health.

In the northern countries, especially Finland, massage is a very old science, a much-respected art. One of the greatest specialists then at Helsinki, a Dr Kollander, came to the military hospital to treat difficult cases. There he met Kersten and, recognising his gift, took him as a pupil.

The next two years were full of material hardships for the young man. He did not miss a single class or a single exercise, and at the same time to make ends meet he worked as a dockworker, a waiter and a dishwasher. But he had a strong constitution and a ferocious appetite, which could put up with anything. Where another would have wasted away, he flourished.

In 1921 he received his degree in scientific massage. His teacher told him, ‘You must go to Germany to continue your studies.’ Kersten agreed. Shortly afterwards he arrived in Berlin, completely penniless.

The problem of a lodging was the easiest to solve. Kersten’s parents had an old friend in the German capital, the widow of a Professor Lube, who lived with her daughter, Elizabeth. The Lube family was not rich, but they were well-educated, cultured people. They were only too happy to provide refuge for the poor student. As for the other essentials – food, clothing, registration fees – Kersten got along as he had done at Helsinki, by doing whatever odd jobs he could find. He washed dishes, worked as a film extra, and sometimes, at the recommendation of the Finnish Embassy, he acted as an interpreter for Finnish tradesmen and industrialists who were passing through Berlin on business and did not speak German. There were good weeks and there were very bad ones. Kersten was not always able to satisfy his appetite, which was enormous. His clothing left much to be desired. The soles of his shoes often gaped. But he bore his poverty with patience. He was young, strong, proof against any test and of a balanced and optimistic disposition.

Moreover, he had found someone to turn to in his worst moments: Elizabeth Lube, the younger lady of the house, but considerably older than he.

Their friendship was direct and spontaneous. Elizabeth was a very kind, intelligent and active person. She needed an outlet for her inner resources, and this great young man who was so brave, healthy, cheerful and poor and who had landed on her mother’s doorstep one morning, seemed the answer to her prayers. As for Felix Kersten, obliged once again to start life in a strange place, without money or family, how else could he respond to her unfailing devotion except with wholehearted gratitude and affection?

Then, too, Kersten had the liveliest appreciation for feminine companionship. He saw in the young ladies and women who attracted him the same creatures who graced the pages of the German and Russian romantics whom he had read so avidly. They were angels, they were poetic visions. He treated them with an old-fashioned gallantry and the most exalted respect. Perhaps this manner did not exactly go with his ruddy complexion, his premature stoutness, his calm and dignified bearing. But as it happened, the ladies adored him. He was a great success. Were his relations with them only platonic? It would be hard to believe; food was not his only form of indulgence.

But with Elizabeth Lube his relations never went beyond the realm of pure friendship. It is possible that this reserve sprang from the difference in their ages, but it seems more likely that its real cause lay in a sort of unconscious prudence on the part of the two friends. Elizabeth Lube and Felix Kersten knew their friendship to be so rare and so precious that, by a kind of instinct, they kept it apart from the risks and upheavals which always threaten another sort of feeling. They were not mistaken, for their bond lasted almost forty years. The wanderings of a lifetime, changes of fortune, of home, of family situation, the tragedy of Europe, and five terrible years for Kersten only served to reinforce the strength and beauty of this spiritual tie formed in 1922 between the daughter of a good bourgeois family and the poor young student.

All this came about simply, day by day, without fancy words or gestures. Elizabeth Lube mended, washed and ironed Kersten’s linen and clothing. And when the day arrived that the young man was in desperate need of new shoes, Elizabeth Lube secretly sold (he did not know about it until much later) the one small diamond she had once inherited. While she darned and mended, Kersten told her of his hopes and dreams, or concentrated on his studies. He has said that for him she was both an older sister and a mother.

Professor Bier, the internationally known surgeon, was teaching in Berlin at that time. This distinguished master, who had received all the official honours, nonetheless took a passionate interest in certain medical techniques which the faculty looked upon as unorthodox: chiropractic, homeopathy, acupuncture and, above all, massage.

When Professor Bier heard that one of his students was trained in Finnish massage, he singled him out, became friendly with him, and told him one day, ‘Come to dinner tonight. I want you to meet someone who may interest you.’

As Kersten made his way into the huge, brilliantly lit rooms, he noticed sitting near his teacher a little old Chinese gentleman whose face, which was completely covered with tiny wrinkles, never stopped smiling above a scraggly grey beard.

‘This is Dr Ko,’ Professor Bier told Kersten.

The great surgeon had pronounced this name in a tone which surprised Kersten, because of the deep respect it held. Dr Ko did nothing, said nothing, at least at the beginning, to justify such a tone. Professor Bier carried the conversation almost single-handed. The fragile old Chinese man confined himself to shaking his head in short, rapid, polite nods and smiling interminably. From time to time the black eyes that missed nothing would stop twinkling, and survey Kersten with a remarkable intensity. Then wrinkles, smiles and twinkling eyes would resume their lively and amiable little game.

Then all at once, in the most simple and unaffected way, Dr Ko told the young man his story.

He was born in China, but he had grown up inside the walls of a monastery in north-eastern Tibet. There he had been initiated from childhood not only in the teachings of philosophy, but also in the Chinese and Tibetan arts of healing as they have been handed down from generation to generation by the lama-doctors. And above all, the ancient and subtle art of massage. After he had devoted twenty years to these studies, the head of the monastery sent for him and said:

‘We have nothing more to teach you in this part of the world. You will be given sufficient money to live in the Occident, so that you may study with the experts there.’

The lama-doctor arrived in England, enrolled in one of the universities, and spent the time that was required to earn the degree of doctor. Then he set up practice in London.

‘I treated my patients by using massage, as it is taught up there, in our Tibetan monasteries,’ said Dr Ko. ‘It was not from pride that I did this. A lama, in his training, lays aside all vanities. It was because I thought that in Western science I was no better than a novice, surpassed by countless other excellent doctors. While on the other hand, I alone in that country was skilled in the methods of curing which have been practised in China since the dawn of time.’

‘And Dr Ko has done wonders,’ said Professor Bier. ‘His colleagues, of course, call him all sorts of names. I wrote to him, and he has done us the honour of coming to work here in Berlin, under my absolute protection.’

These words made a profound impression on Kersten. One of the foremost authorities in the world, a man with the best scientific training, had absolute confidence in this tiny wrinkled figure from the rooftop of the world!

‘I have told Dr Ko about your studies in Finland,’ continued the professor, ‘and he asked me if he could meet you.’

Dr Ko rose, bowed, smiled and announced, ‘We must leave our host. We have already imposed on his patience.’

Professor Bier’s home was in the neighbourhood of the Tiergarten. Late strollers in the park that night might have seen, wandering among the dark groves and statues of royalty, two contrasting figures: one tall, broad and young, the other tiny, spare and old. They were Dr Ko and Felix Kersten. The lama-doctor questioned the student exhaustively. He wanted to know everything about him: his background, his family, his temperament, his education and, above all, what he had learned from his teachers at Helsinki.

‘Very good, very good,’ said Dr Ko at last. ‘I live not far from here. Let us continue our conversation at my place.’

As soon as they were in his apartment, Dr Ko took off his clothes, stretched out on the sofa, and asked Kersten, ‘Would you please demonstrate your Finnish technique for me?’

Never had the young man concentrated so hard as he did on kneading this tiny body, so fragile and parched. When at last he straightened up from his work, he was very pleased with himself. Dr Ko dressed himself, regarded Kersten with his twinkling eyes, and smiled.

‘My young friend,’ said he, ‘you know nothing, absolutely nothing.’ He smiled again and went on, ‘But you are the one I have been waiting for, for thirty years. According to my horoscope, fixed in Tibet when I was still a novice, I was to meet this very year a young man who would know nothing, and to whom I would teach everything. I would like to take you for my pupil.’

That was 1922.

The papers were beginning to speak of an inspired madman: Adolf Hitler. And among his most fanatical supporters, they mentioned a schoolmaster named Heinrich Himmler.

But these names meant nothing to Kersten, who was discovering the wonderful art of Dr Ko.

What Felix Kersten had learned at Helsinki and what Dr Ko was revealing to him must both be described by the term ‘massage’, since the two schools had the common aim of giving the hands the power to relieve and cure suffering. But as he absorbed the lessons of his new teacher, Kersten came to realise that there was otherwise very little in common between the Finnish school (which he knew, moreover, to be unrivalled in Europe) and the tradition of the Far East, whose basic principles and methods the old lama-doctor was passing on to him.

The Finnish method now began to seem like a primitive and almost blind groping in the dark, which could only hope to grant the most superficial, random and temporary cures. The other method of manual therapy, the one with such ancient and distinguished origins, had at once the precision and versatility of wisdom and intuition. It went right to the core, to the marrow of the subject to be treated.

According to the Chinese and Tibetan science, as it was taught by Dr Ko, the masseur’s first duty was to find out, without any outside help and without paying any attention to the patient’s complaints, the exact nature of the pain, and to ascertain its source. How, indeed, could one hope to cure an illness without knowing its origin?

To aid him in this crucial diagnosis, the practitioner had at his disposal the four pulses and nerve centres and networks of the human body, which had been enumerated and recorded in Chinese medicine for centuries. But his only instrument of auscultation was the flesh on the tips of his fingers.

It was this flesh, then, that had to be trained, educated, refined, sensitised to the point where it could perceive the malady lurking under the skin, the fat and the flesh, and determine which nerve group was affected. Only then was it of any use to know the outward gestures, that is the palm and finger movements which could influence the nerves in question and, thanks to the accuracy of the diagnosis, relieve or eliminate the pain.

Nevertheless, the mastering of these movements was not the most difficult part.

Obviously, to be completely familiar with the topography of the nervous system, to know just the degree of pressure, just the kneading action, just the delicate twists and turns necessary to correct a given weakness, and to be able to execute all these with the greatest efficacy, required a long and painstaking apprenticeship. Few pupils had the ability to succeed. But the essential secret of the art was the ability to locate with the tips of the fingers the essence of the malady, to measure its severity, and to know from what vital centre it sprang.

The most refined, extensive knowledge of the epidermis was not enough. In order to render the tiny tactile antennae capable of recognising all the nerves of the human organism and of responding, as it were, to their plea, the practitioner had virtually to leave his own body and enter that of his patient. This could only be attained through the age-old methods of the great religious disciplines of the Far East which, by means of spiritual concentration, special respiratory exercises, and inner states taken from yoga, bring the mind and senses to a degree of acuteness and intuition otherwise unattainable.

What seemed like second nature to Dr Ko, who had been dedicated from infancy to the training and meditations of the lamas, was terribly difficult for a Westerner, particularly one of Kersten’s age. But he had the ability to work at it, tremendous willpower and also, of course, the aptitude.

For three years he spent every minute with Dr Ko when he was not attending courses or working at the odd jobs by which he earned his living. Only then did Dr Ko say that he was satisfied with him.

Having assisted the old lama in his work, Kersten had seen him perform some remarkable cures, some of which seemed almost miraculous. Of course, they were limited to a very definite area; Dr Ko did not claim that his therapeutic massage could cure everything. But its range was so great (for the nerves play a role in the total organism, whose extent and importance Kersten would never have known without studying Chinese medicine) that it was beyond the dreams of the most ambitious practitioner.

In spite of the great poverty in which he continued to live, these three years went very quickly for Kersten. Not only did he follow Dr Ko’s teachings with a joy and admiration which grew greater every day, but he came to feel for his teacher a fondness and respect which also deepened as time went by.

There was nothing of the ascetic about Dr Ko. To be sure, he forbade the use of alcohol and tobacco, which dulled the sense of touch. But Kersten had never formed the taste for these stimulants. On the other hand, the lama-doctor approved of eating well. He did his own cooking and often invited Kersten to share his excellent chicken broth with rice. As for physical relations with women, he considered them highly salutary for the proper balance of the nervous system.

Gentleness, courtesy, unselfishness, equanimity and courage all contributed to Dr Ko’s calm and happy acceptance of life, which never failed him. And Kersten, so big and robust, felt as if he were under the wing of the little old Chinese man who never stopped smiling.

Thus the news he received one autumn morning in 1925 was quite a shock to him. Kersten had just arrived at his teacher’s house. The latter told him very calmly, ‘I am leaving tomorrow to return to my monastery. I must begin to prepare myself for death. I have less than eight years to live.’

Kersten stammered, ‘But that’s impossible! You can’t do it . . . But how do you know?’

‘From the most trustworthy source: the date was established long ago in my horoscope.’

Dr Ko’s voice and smile had their habitual gentleness, but in his eyes Kersten saw an irrevocable decision.