Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Influx Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

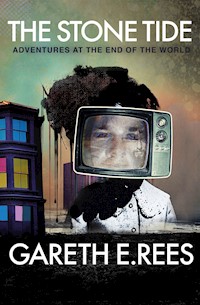

When Gareth E. Rees moves to a dilapidated Victorian house in Hastings he begins to piece together an occult puzzle connecting Aleister Crowley, John Logie Baird and the Piltdown Man hoaxer. As freak storms and tidal surges ravage the coast, Rees is beset by memories of his best friend's tragic death in St Andrews twenty years earlier. Convinced that apocalypse approaches and his past is out to get him, Rees embarks on a journey away from his family, deep into history and to the very edge of the imagination. Tormented by possessed seagulls, mutant eels and unresolved guilt, how much of reality can he trust? The Stone Tide is a novel about grief, loss, history and the imagination. It is about how people make the place and the place makes the person. Above all it is about the stories we tell to make sense of the world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 352

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Gareth E. Rees from Influx Press:

Marshland: Dreams and Nightmares on the Edge of London

The Stone Tide

Adventures at the end of the world

Gareth E. Rees

with illustration by Vince Ray

Influx Press, London

Published by Influx Press

49 Green Lanes, London, N16 9BU

www.influxpress.com / @InfluxPress

All rights reserved.

© Gareth E. Rees, 2018

Copyright of the text rests with the author.

The right of Gareth E. Rees to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Influx Press.

First edition 2018. Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd., St Ives plc.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-910312-07-0

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-910312-27-8

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-910312-08-7

Editor: Gary Budden

Copy-editor/Proofreader: Momus Editorial

Cover art and design: Mark Hollis

Comic: Vince Ray

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

In memory of Mike Hughes

1974—1996

‘Hastings is the gateway into an enchanted garden … Between the hills and the sea it lies—the most romantic province in this England of ours. Scarcely a place in it seems to belong to this present: from end to end it is built up almost entirely of memories … nowhere in our coasts shall you find a stretch of land so crowded with the ghosts of dead men and dead empires.’

Walter Higgins, Hastings & Neighbourhood, 1920

Contents

PART ONE – ARRIVAL

Gull Terror

On the Rocks

The Bare Bones

The Lost World

The Eel with a Head the Size of an Armchair

Storm Surge

Pissing on the Ridge

Driving Mr Wicked

Smoked Cats

The Black Arches

Arthur Conan Doyle and the Monkey Man

The Spirit Molecule

The Battle of Carlisle

PART TWO – DWELLING

The Dead Shore

Mad John

The Cave

The Fallers

Crossing Over

Flotsam

Lair of the Limpet

The Homecoming

PART THREE – DEPARTURE

Between Floors

The Eye of Horus

Blood on Netherwood

Through a Scanner

The Great Convergence

PART ONE

Arrival

‘I’m gonna move to Hastings,

Go as low as high can go

We all suck on Hastings rock,

It’s the hardest rock I know’

Salena Godden

I

Gull Terror

In our final days in London, Emily’s granddad had a stroke. His head hit the floor and cracked like an eggshell. He was ninety-six years old. There was nothing that could be done, the doctor said. They had to let him go. But he was a farmer in his working days and he had the heart of an ox. His body refused. He hung on, ailing on a Southampton hospital bed. We had no choice but to carry on with our move. Our life was in labelled boxes, ready for loading. A younger couple with a new baby were eagerly waiting for us to leave. Our time was up.

Emily and I had bought a dilapidated Victorian terraced house in the East Sussex seaside town of Hastings. No central heating. Antiquated wiring. Damp and dry rot. Overgrown garden. Foliage in the guttering. Cracked chimney pots. It was what estate agents call a project.

At the viewing we found the owner, Angela, hunched in the corner of the living room like a frightened bird, surrounded by books, cats and mouldering furniture. She and her husband had bought the house with another couple in the early 1970s and converted it into two separate properties. Their arrival marked the end of an era. The house had been occupied for almost a century by the family of the Victorian who built it. After constructing the terrace, he’d chosen to live in this property because it had the lowest resale value. Being situated on a bend in a road, it was wedge-shaped with peculiarly angled rooms. It remained in his family until Angela’s lot came along with their woodchip and plasterboard partitions.

Now both husbands were dead and only the two women remained. Unable to deal with the crumbling house, they retreated into two rooms on separate floors and gaffer-taped electric fireplaces into the surrounds. Eventually, Angela was left alone to sell the place on. When we came for the viewing it must have been heart-wrenching for her to see Emily and me in her home with our two daughters, ready to knock down what she had made, paint over all she’d known and replace her memories with our own. We should have realised she’d not go quietly.

Two days before we were due to move, a distressed Angela rang the estate agent and told them she needed more time. But things were too far gone. There was a chain of people with contracts signed and removal firms booked. There was no going back.

Emily phoned Angela. ‘Are you okay? Can we help?’

‘I was sitting here, looking out the window at the park,’ said Angela. ‘I don’t know if I can leave … all this …’

‘It’ll be a family home,’ said Emily. ‘We’ll look after it.’

‘I don’t know. I haven’t packed any of my things yet …’

‘If you want to leave some bits and pieces behind to pick up later, that’s fine.’

‘I feel like I rushed into this, I—’

‘Is there anyone who can help you?’

Angela explained that she had a nephew with a van who she could ask to come and shift the furniture, though she barely saw him these days. He didn’t visit. Never called around like he used to, not like in the days when all the family lived here, when her husband was alive. She had been left alone to deal with this change. It had all happened so quickly. Forty years in this place and now her possessions had to be cleared in a matter of days. She wasn’t prepared. But her nephew, he was a good lad. Did she mention he had a van? He could do two trips, or three if necessary. There was so much to get rid of. Perhaps if we could wait another week or two? He was very busy, always working, but his van would be ideal. A few weeks, maybe more. That would give her time to prepare. How about that?

Emily gently convinced Angela that it was out of our hands. She had no choice but to move on the completion day. But we suspected she would be there when we arrived with the removal truck. What would we do then? Haul her out by her ankles? Legalities aside, this was her home. Her life was in these walls.

The death of Emily’s granddad on the morning of the move intensified the feeling that we were changing the generational guard. After a sombre drive from London, we pulled up beside the overgrown front garden, white lilies pushing through the weeds.

‘Hello?’

There was no sign of Angela. No sign of life at all. It was as if nobody had lived here for decades. Light strobed through moth-eaten holes in the curtains. Cobwebs darkened the corners of walls blistered and pimpled with damp. A stink of rotten earth wafted from the cellar. Racing green Victorian paint peered from beneath a flap of 1950s wallpaper. On the plaster beneath was a handwritten signature, dated 1885. I couldn’t make out the first name, but the surname was Marsden. After the final letter, the signature looped across the plaster and mutated into a cartoonish portrait of a man with a beaky nose and a bird-like body, perhaps that of a duck or herring gull. Most likely, this was the man who built our house.

Beneath his zoomorphic self-portrait were scrawled other names and dates. Tom and Margaret who visited on 21 July 1973. Anne and Dick from Cardiff. Olive Strange. Sam (aged five) and Cherie (aged seven). Hilary. Tony. Ron. Jim. Isabel. Presumably they were all friends of Angela’s who had come to Hastings to muck in with the project and get a bit of sea air at the same time, wandering to the arcades, eating ice cream on the pier, running down the shingle with their trousers rolled up. What wonderful luck to know people who lived in a holiday town. Of course, they were happy to come down for the weekend and help get the house into shape. Angela only had to ask. According to the dates on the wall, the renovation started in June 1974 and ended in August 1975. When the project came to an end they made valedictory marks on the plaster and sealed them beneath wallpaper.

‘It’s all coming to the surface now,’ I said.

The absence of those former residents and their visitors hung heavy. Above the front door, a cracked stone lintel was the house’s broken heart. Its subsiding interior had the wonk of an eighteenth-century galleon. There was an oppressive gravity to the place, as if it could no longer bear the weight of its own existence. We crept up lopsided stairs, running our hands over woodchip. In one of the bedrooms a disintegrating carpet revealed a layer of newspapers dated 1989–90. I read the headlines. A story accusing Rupert Murdoch’s papers of distorting the facts about the recent Gibraltar IRA killings. A commercial for a brand-new channel called Sky Movies. Afghanistan peace talks in deadlock. A smiling Colonel Gaddafi with a crowd of cheering supporters. Shopworkers defiant against the unions over Sunday trading laws. A warning about ozone depletion in the atmosphere. War, politics, television, environmental collapse. The same old news cycle, spinning in a whirlpool of time.

In the yard, a handless clock hung on the wall. A pipe jutting from a concrete wall oozed slime into a vat. Steps led to a vertical jungle of weeds and a fox den, overlooked by an ancient yew, entwined with the branches of a tree which had grown and died within it. Pushing through the nettles and briars we found sculptures strewn in the undergrowth: snake heads, an urn, an owl, two ducks, a sleeping lion. Somewhere beneath this thorny tangle was a garden that had once been landscaped, illuminated and resplendent with clay sculptures. A temple to al fresco living. Like Machu Picchu it had been hurriedly abandoned, its totems and symbols swallowed up by nature. There was a metal handrail to help the unsteady visitor but it was buckled and rusted. Not to be trusted by someone with frail bones. Angela can’t have been up here for years. As we explored further, our cocker spaniel Hendrix tore through the undergrowth, crazed by the scent wafting from the fox den. Worried he’d escape into the private allotments at the back of the garden we ushered him into the yard and wheeled a tabletop in front of the steps to seal off the wilderness.

That night we lay on a mattress beneath a broken chandelier in a room the colour of dried blood. It was hard to sleep. Our frantic toing and froing had kicked up years of dust. Our chests were wheezy. Eyes gritty. Noses clogged. Damp, cold air seeped through the bedclothes and made us shiver. Outside the window, shark-faced boomerangs appeared, seagulls caught in the glare of street lamps. They circled our house all night as if we were fresh meat washed up by the tide.

When I woke the next morning, I could hear my daughters giggling next door. They seemed excited at least. Wearily, I shuffled into their room to check that they were okay, but they were both fast asleep.

My throat tightened. These weren’t walls which separated our rooms. These were storage vats. Before any renovation could begin, there would have to be an exorcism.

*

The night before Emily’s granddad’s funeral was sickly humid. We were living in the only two rooms upstairs that weren’t filled with boxes, cooking on a camping stove. Downstairs was a no-go area. The kitchen was rotten, with cork panels warped, the paint peeling and the linoleum black and rippled with damp. No oven, only a chasm full of spiders where it used to be. An adjoining bathroom was caked in grime and dead skin. The toilet had no handle, only a cord dangling from a cistern with a sign that read:

PULL IN ADETERMINED MANNERSTRAIGHT UP

This would all have to go. Stripped. Binned. Gutted. Torn down.

Before bed I took Hendrix downstairs for a wee. I cursed and bumped my way through the jumble, then waited in the doorway of the backyard in my pants and T-shirt. He ran up and down the yard, barking furiously. In the darkness I could make out something near the vat of slime by the concrete wall. A white orb, like an eye, swung back and forth as if scanning for something. For me. I could hear clattering and clicking. The scrape of a knife. Hendrix ran up to me, tail low. Freaked out, I led him back into the house and locked the door behind us. Whatever that thing was, I didn’t want to deal with it. I would not die in my pants.

I tried my best to sleep but I could not shut out the noise of whatever was in our yard. It beat something repeatedly against the side of the plastic slime vat. The noise was slow and rhythmic, the tempo of a New Orleans funeral march—BANG—BANG —BANG.

Next morning, Emily and I went to investigate. As soon I opened the door there was an eruption of clattering and a startled cry. The culprit emerged from behind the slime vat: a herring gull with its head cocked at an awkward angle. It lumbered in a circle then back to its corner, ricocheting drunkenly between the slime vat and the wall. It looked like it had suffered a stroke.

‘You’ll need to get it,’ said Emily.

‘What do you mean get it?’ I stared in horror at the bird with its blank eyes and hooked beak. It was cornered. Close to death, with nothing to lose. This wasn’t right. Could it be coincidence? This thing—now—in our first week here?

‘It’s frightened,’ said Emily.

‘It fears nothing,’ I said. The bastard was giving me a look that I’d never seen on an animal before. An expression of sheer malevolence. I suspected that this was no ordinary herring gull but more likely a diabolical incarnation of Mr Marsden, the bird-like Victorian builder who had depicted himself on the plasterwork.

‘Damn you, Marsden,’ I muttered.

‘I’ll get you something to protect your hands,’ said Emily.

Next thing I knew I was crouched low, wearing a pair of oven gloves, in a face-off with the fiend. I scuffled towards Mr Marsden, grimacing. He lumbered backwards and began scraping his beak against the kitchen wall like a gangster with a blade. We glared at each other. I tried to hide my fear but my pulsing Adam’s apple gave the game away. He lurched into a run, forcing me back into a flower pot. I counter-charged but the bastard waddled behind the slime vat. For a while he thwacked his head angrily against the plastic, then he was out again, staggering in circles.

‘Fuck this.’ I threw down the oven gloves.

Even if I could grab the bird, I had no idea what to do next. Take it to A&E? Dump it on the road? Tear out its beating heart and offer it to the gods? We had to drive to Southampton for a funeral. If we hung about any longer we’d be late. Nature would have to take its course. I wheeled the tabletop away from the steps: an invitation to the foxes beneath the yew tree. We piled the kids into the car and took off at speed, leaving Mr Marsden looping around the yard.

When we returned the next afternoon, he was gone. All that remained was a knocked-over plant pot and a gull feather. I hoped this sacrifice was enough to placate the house. Until now, it had been a museum of other people’s memories. But things had changed. The gull was in our story. The first of many. Because like it or not, we were here to stay.

We’d all just have to learn to get along.

II

On the Rocks

Shortly after my first daughter was born I developed a serious walking habit. Every lunchtime I’d close the door on the nappies and caterwauling and head across the Walthamstow marshes, Hendrix by my side, jotting down notes and taking photos of abandoned sleeping bags, crow carcasses and crumbling water filtration systems. Eventually I wrote a book about London’s marshland that was well enough received to justify my daily absconding and I was not going to give up the habit now that we’d moved to the seaside. This town was where the sex magician Aleister Crowley came to die, John Logie Baird carried out his first television experiments and the Piltdown Man hoaxer lived as a child. There were new stories to be found and new reasons to get out of the house. The lower floor was effectively derelict. Storage for boxes we could not unpack until the renovation, which could take many months, had claimed the space. ‘Don’t expect this to be quick,’ warned Emily. There were walls to knock down, tradespeople to call for quotes, specialists to come and assess the damage. It meant we had to huddle in a makeshift upstairs kitchen full of decayed furnishings, heating our supermarket ready meals on a camping stove. We threw out the stair carpets and all the curtains to get rid of the musty smell but even with the windows propped open the air was fungal. A layer of grime coated every surface, as if someone had been using the house to cook pots of human fat. Emily spent an hour scrubbing dead skin from the bath, retching and heaving.

‘I wonder if any of the dead skin is from someone who is now dead,’ I said, watching from the doorway.

‘Don’t,’ said Emily.

‘Imagine, the final piece of you that survives on this earth—a black ring on a bathtub.’

‘You’re not helping.’

Quite frankly, I couldn’t wait to get out with the dog. The sea, the sea, the sea was the place to be. As soon as I got the opportunity, I escaped to the bottom of our road, where an embankment carried the railway line above an underpass which led into Morrisons’ car park, then Queens Road, a scruffy Victorian street lined with bridalwear shops, nail parlours and mini-markets displaying rows of luminescent bongs. I hadn’t realised that bongs were such an essential impulse purchase. Folk liked their weed here, clearly. They liked their fags and booze too. Outside the Priory Meadow shopping centre, rows of pensioners smoked on benches. A man pushed a buggy, can of lager in his hand, a three-year-old girl trailing behind. She kept getting in the way of oncoming pedestrians. ‘Bastards,’ the man seethed under his breath. Then he turned to his daughter, ‘Just tell them all to piss off.’

After London, the street lamps seemed absurdly tall. Their gargantuan bulbs glared at me as I circled the town centre where French students tossed coins at a busker in exchange for ‘Here Comes the Sun’ and teenagers giggled at the raffish temporary tattoo vendor. I strolled up Robertson Street until I came to a road that separated the town from the promenade. I waited to cross by a lamp post covered with wilted flowers, Stella cans and the words ‘Gone But Not Forgotten’. A man in his forties stared out from a photo. Cars whished past unheedingly.

On the promenade, I leaned against railings where danger signs warned ‘Falling Debris’ and a poster advertised a concert by The Upbeat Beatles.

COME AND PARTYLIKE IT’S 1963!

Hastings Pier was a charred skeleton. The remains of a campaign banner, flapping from the rusted gantry, bore the word ‘SAVE’. Information boards on the hoardings told the story of a renovation which had not yet commenced. On the walls of the visitors’ centre, artworks blended sepia photos of the pier in its heyday with colour shots of what it might look like when the works were completed. Edwardians strolled beside happy families from the future while hot air balloons and jet planes jostled for supremacy in the sky.

Steps led me to the beach. It was low tide. The shingle gave way to a slab of sand, shimmering like raw steak, peppered with shells. The air shifted and warped. Heat, possibly, rising from the earth, or something else. Mesmerised, I lost all sense of the town behind me. There was only sand, sea, rocks, sky. A gust of salt air whipped into my nostrils. It carried a memory. Or not even a memory, but the very sensation of a moment long forgotten, as if the past twenty years had never happened and I’d crossed a time-space dimension to the West Sands of St Andrews, on the coast of Fife, 900 miles north, in 1996. It was the beach where they filmed Chariots of Fire, a long curving paleness against the wide muddy blue of the North Sea, stretching towards the cathedral and castle. My best friend Mike was a little ahead, in jogging bottoms and a T-shirt, despite the chill, turning back to me and laughing. ‘Come on,’ he said, ‘you fat bastard.’

He’d challenged me to a run that morning, teasing me about my nascent beer belly. In my years at Sheffield University I’d done little more than booze and read. By the time I came up to St Andrews to study for a Masters, Mike was in training for the army. They made him do things like haul a backpack of rocks up a Munro without any sleep while being attacked by ninjas, or so he told me. He could be full of shit. But I couldn’t deny the evidence on the beach as he accelerated away from me with surprising speed. Faster. Stronger. Unstoppable.

Lungs heaving, I crumpled onto the sand and watched him run towards his destiny.

That castle, looming.

*

There was a castle in Dover, where Mike and I first met at school in 1985 and later became best friends. We’d pass it on the way into town to go underage drinking on Saturday evenings, wearing ridiculous sports jackets we’d plundered from charity shops to make us look older. There was a castle in St Andrews too, from which Mike would fall. And there was one here in Hastings, though it was little more than a few crooked teeth on the jaw of West Hill’s cliffs. On the vertiginous rocks beneath the ruin, teenagers huddled in folds of sandstone and looked toward France. Like Mike, they liked to climb, to live on the edge. Kids these days, same as kids those days. Some joker had graffitied an eye onto a bulge in the rock, giving West Hill the appearance of a beached leviathan. It watched me dolefully as I shambled along Pelham Beach, unused to the effort of walking on shingle, that constant falling away, the fizz of water percolating, a thousand micro-rivers changing course beneath my step. I tried to focus on the stones, forcing the apparition of Mike back from whence it came, not allowing the tide to take me into that deep history. Until this moment, it hadn’t occurred to me that I’d retained such a powerful connection between the coast and what happened to Mike. Or perhaps this was happening now because of the imminence of my fortieth birthday, the gloom of the house we’d bought and the uncertainty of my place here. No friends. No personal history. No link to the locale but only to the sulphurous algae and churn of waves I’d known in St Andrews two decades ago. Whatever the reason, I wanted to dismiss the memory and embrace my new life. Look forward. See what was there before my eyes.

Up ahead a man in a high-visibility jacket swung a metal detector over wavy lines of kelp. A girl and her boyfriend smoked on a pebble ridge. Out on the wet sand, the lean silhouette of a lugworm fisherman hunched over his pump, a dog barking in circles around his bucket. I came to a crooked outfall pipe jutting out from the beach, gushing lime green freshwater into the sea. Beyond was a long line of hollows in the shingle where someone had walked earlier. I followed it, placing my feet in the pits their feet left behind. There was something forlorn about the way the trail meandered. For me, these prints were as poignant as prehistoric footprints exposed on Norfolk shorelines by storm tides. After all, what’s the difference between an 850,000-year-old human footprint and one that’s five minutes old? In the grand scheme of things, we are all fellow ancients, sharing the blink of an eye.

I cut up from the beach, over the miniature railway line, past the go-karts, trampolines, funfair and amusement arcade. Elvis stared out from the side of a slot machine. Next to him Sooty, Soo and Sweep were trapped in a glass box, playing synth-pop cover versions for a pound a go to feed their crack habits. Soo’s voice sounded hoarse. After each song finished, a prize dropped through a slot. It felt a bit desperate.

Through a smog of hot dog and candyfloss fumes I drifted onto Rock-a-Nore Road, where tourists waved gulls away from polystyrene pots of cockles and snapped photos of the eighteenth-century net shops—huts for fishing equipment, tall and black lacquered. A Kinks track blasted from the Lord Nelson, where fishermen unwound after work. On the pavement outside the pub, a skinny old man in a suit stood by an upturned bicycle, smoking a rollup, frantically turning the pedal so that the back wheel span. I hung nearby, watching, noting down what he was doing on my iPhone.

The road on which he operated his spinning machine was called The Bourne, a brutal slab laid over the stream which once trickled through the Old Town, dividing it in two. Perhaps this was an ex-fisherman performing a rite by the ancient waterway, mimicking the winding of a winch. He seemed nervous, jittering from foot to foot. Whenever the wheel slowed he glared at it caustically, then gave another turn. I slipped from the shadows for a closer look.

He stepped out, furious, and yelled, ‘Stop copying my fucking idea!’

I backed away, guiltily slipping my iPhone into my pocket. By the time I reached the net shops, he was at his wheel again, turning, as if nothing had happened. Leaving him to it, I hurried past the Fishermen’s Museum, once the community’s church, to the aquarium and the car park. I kept walking as far as I could, until everything stopped. The town ended abruptly at railings festooned with warning signs. Sandstone cliffs stretched into the horizon. The walkway dropped onto a beach of weathered rock, wet slabs tilted like broken tables. The vinegar stench of seaweed. Yawning mussels and the stripped bones of a fish. A rusting anchor. Fisherman’s rope. Plastic bottle.

Things returned that had been taken away.

Now there was no stopping it. Memories of that May day in 1996 came flooding back—sudden, surprising and visceral. As I stood before the Sussex shore’s ragged maw, listening to gulls cry and waves churn, I was transported to the beach beneath St Andrews Castle, the tide low beneath a bleached sky, my young heart beating hard, a metallic taste in my mouth. I could see Mike lain on a broken rib of stone where the dog walker found him earlier that morning. He was curled up as if asleep, still wearing his tweed jacket, jeans and leather-soled shoes, looking so tiny between the foot of the castle and the vastness of the sea that had brought him home. There were already police on the beach. People crying. I joined my flatmates in a huddle and we stared out in silence, trying hard not to believe.

They sent Ben out to identify the body. He walked towards the rocks, surrounded by coppers, head bowed like a condemned man. Mike often crashed on someone’s floor or slept over at his girlfriend’s house. There was a chance he was warm and naked in her arms, sleeping off the whisky, and this was some other poor bastard for others to cry about. But we knew Mike, and we knew what we’d been up to the previous night, and how he hadn’t come home. We knew what Ben would find. And Ben knew most of all, picking his way over the rock pools towards the inevitable.

That afternoon, when the police had done their probing and left us to drink, reminisce and cry, we stood on the second-floor landing, talking to friends who came with condolences. I heard the latch on the front door and looked down through the stairwell to see a hand gripping the bannister and a head of red hair hung down, like someone about to reveal a shocking secret, tortured by the imminence of his shame, footsteps slow and plodding. He wore a tweed jacket, corduroy jeans and leather shoes, just like—just like … had anybody else noticed this? No, they were all chatting drunkenly, the idiots. I tried to alert them to what was happening but I was transfixed on the pale hand sliding up. It couldn’t be, but this was Mike returned. Christ knows how it was possible but this whole thing had been a mistake. A slip-up. An oversight. A joke. What a total and utter bastard. To make us think he’d gone like that. Brilliant. He had always been brilliant. As close to a genius as anyone I knew.

I got ready to welcome him at the top of the stairs, tears welling, arms outstretched. But when he got to within a few metres and lifted his face it wasn’t Mike at all. It was a guy called Charlie and his hair wasn’t red, but blond, and he was half a foot taller than Mike. I couldn’t understand it. I knew what I had seen. For that minute, I had existed in an alternate universe where my friend was alive, having played the most fiendishly sick prank. It was as good as real, for fuck’s sake, as good as real.

Charlie stretched out a hand to shake mine. ‘I’m so sorry,’ he said.

Not as sorry as I was.

III

The Bare Bones

Beneath the woodchip modifications, a Victorian house was waiting to be revealed. Emily and I stood on the staircase in masks, and swung mallets at the partition wall that separated the stairs from the hall. Boards exploded. Beading dangled. We were talcum-powdered with plaster dust, as white as ghosts. As splintered panels fell away we beheld an ecosystem that had flourished for forty years in the gap between wood and woodchip. Clusters of spider legs were shrouded in silk and human hair. At our touch cobweb curtains fell open to expose wooden panels, along which tiny black pods ranged like climbers on an ascent. I wondered if they were some terrible new lifeform gestating, waiting for the light.

‘What’s that?’ I pointed at something in the debris. A child’s shoe. Sealed within the partition wall for forty years. Why was it put there? To ward off evil spirits? Emily replied that sometimes a shoe in a wall was just a shoe in a wall.

Day by day, month by month, we peeled back the flesh of the house. Beneath the brown 1970s wallpaper we found 1950s wallpaper—dazzling suns in golden circles. Beneath that, 1920s wallpaper. Then a Victorian jungle of flowers and geometric shapes. But we had to go even deeper. Dry rot had spread from floor to dado rail on the ground floor. A specialist came to sort it out. He pulled away the plaster to reveal a ribcage of Victorian laths. Exposed to light, grains of mummified matter poured from the holes, as if from a pharaoh’s tomb.

Next, we tried to find the source of the musky damp air. Emily yanked up the floorboards to reveal a mess of fluff and pipes littered with bottle tops, pen lids, wrappers, fingernails. It was horrifying how much life had accumulated in these hidden spaces. Behind a water tank in the kitchen we found a box of Tampax from the 1980s.

‘Wow, they’re a real period piece,’ I joked. But really, I was aghast. ‘How can something like that stay there for so long? Who put them there? Why? And how can it be that nobody looked in that spot again for another thirty years?’

Emily told me that she didn’t know but if I couldn’t cope with other people’s memories, then perhaps I should move into a flat in a new-build somewhere.

‘You can take the dog with you,’ she said.

*

The renovation was Emily’s idea. She was the practical one. I was a freelance writer cursed with poor hand-eye coordination and a pathological fear of electricity. But Emily was mechanically literate, able to see how things could be deconstructed and reconstructed. Anything she didn’t know, she could learn after ten minutes on a laptop. If there was a plug to change, a computer to fix or shelves to build, Emily was the woman for the job. She could screen print, tile, dye, upcycle, sew, remake and renew. She breathed life into dead things.

When I met Emily she was recently out of university, where she had studied art history. She worked in customer services for an investment newsletter company, answering phones and taking abuse from elderly gentlemen with too much time on their hands. She let them rant about how terribly they’d been served by the latest stock recommendation, that the markets weren’t working as predicted and they wanted their money back. She’d defuse their ire with breezy empathy, agree that the world was going to hell and that the best thing they could do to protect themselves was sign up to an even better newsletter for £79 a year. Emily was good at her job. But she wanted to move on to other things. She bought a book called Web Design for Dummies and learned how to build websites. It took her a day. Weeks later she got a job in digital marketing. Just like that. Now she wanted to build something tangible we could live in, and fill it with fabrics and furniture she created herself. She had already enjoyed interior design success with our first London home, with photographs of her work appearing in a glossy style magazine. This was what she wanted to do next. When she fixed her mind on a goal, she was unstoppable.

There was smartness in her genes. Her father was involved in the development of digital TV broadcasting in the late 1980s. He later spearheaded live field trials and walked away with an OBE for his efforts. I didn’t know whether it was coincidence that we’d come to live in Hastings where, in 1923, John Logie Baird used bicycle lights, wax and glue to build the prototype of a machine that would transform the way we viewed the world. Television appropriated an idea that had been around since the nineteenth-century, when occultists sought mechanical means of manifesting spirits. A chemist named William Crookes devised the first radiometer to measure psychic forces and later pioneered work on vacuum tubes, cathode rays and spectroscopy. Others sought to manifest not spirits but the universe itself. The Norwegian inventor Kristian Birkeland, addicted to caffeine and barbiturates, became obsessed with reproducing the Northern Lights in miniature. In the early 1900s he experimented with terrellas—scaled down magnetic models of the earth—to create an artificial aurora at each pole. But in his final drug-fevered days, stricken in bed, he sketched out a far grander vision: a chamber carved into a mountain peak would become the world’s greatest vacuum chamber, with a cathode to charge the particles. Into this he would project images of the planets, stars and aurora. A devoted mass would climb the mountain every Sunday to behold the universe swirling in a cathedral of stone.

Baird had less grandiose aims. He was a serial entrepreneur whose failed ventures included a remedy for trench foot, a new form of soap, and a project for making jam in the open air while he was out in Trinidad—foiled by an attack of sugar-crazed insects. A sickly man who struggled to fend off regular bouts of cold and flu, Baird moved to Hastings to overcome a near-fatal illness. He took restorative walks between East Hill and Fairlight. The blood pumped oxygen to his brain as he huffed and puffed above the town, with ships many miles distant, a suggestion of France’s coastline, Beachy Head, the spit of Dungeness and the concave ocean between: the world the lens of an eye staring into space. Suddenly, his vision was clear.

Baird carried out experiments for television in a workshop above the Queen’s Arcade. One day a 12,000-volt shock threw him across the room, smashing equipment and burning his hands. When the landlord evicted him he moved back to London to continue his work. He would return to the East Sussex coast in 1946, doomed by his final illness. By this time his invention had been superseded by the Marconi Corporation’s cathode ray system and TV broadcasting halted by a world war that had ravaged Europe. But as he sat on a bench by the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill, shivering under a blanket, the English Channel looked the same as it did when he walked the cliffs of Fairlight as a young man. As if nothing had ever happened, or that everything that would happen, already had.

*

Emily invited a stream of tradespeople into the house to pull it back to its bare bones. They erected scaffolding. They tore at the walls. They hacked at the render. They shovelled sand into a mixer. They removed wheelbarrows of rubble. They blared Radio 1’s compressed pop shite from industrial-sized radios. They tried to talk to me about the works.

‘Gareth, mate, do you want the pad stones for the steel exposed or embedded?’

I had no idea what any of that meant. ‘Ask Emily.’

‘Are you going to be moving the soil pipe or keeping it where it is?’

‘God knows. Better ask Emily.’

‘Do you want us to board out the kitchen?’

‘She’s right there,’ I pointed at my wife. ‘Fire away.’

After a while the questions stopped. Now the men leaned coquettishly towards Emily, nodding with amazement at her knowledge of construction methods, fondling their tool belts. Every so often they’d look at me pityingly as I shuffled about with bags of shopping and babbling children.

To make matters worse, on my fortieth birthday I bought a dinosaur. After a pit stop in The Hastings Arms, I stumbled into an antique shop in the Old Town where I beheld a three-foot-high replica of a T-rex skeleton. The man behind the counter told me there was a lot of interest in the dinosaur but if I bought now they’d deliver it for free. Above his head was a row of flying ceramic Hitlers, like those ducks people had on their walls in the 1970s. I was tempted by the Hitlers, but the dinosaur seemed precisely the sort of thing we should own. So I handed over my bank card. By the time I got home I was less sure of the appropriateness of the T-rex skeleton, bearing in mind the state of things. There was a gaping hole where a kitchen had been, protected only by tarpaulin. Boxes blocked the downstairs windows. The electricians were rewiring, so every floorboard was up, bar a central strip no wider than a shoe. I had no idea where we would store a dinosaur skeleton. The only available space was beside our mattress. When the doorbell rang, a disappointed Emily ushered in two delivery men, who carefully carried the T-rex across the walk-board to our bedroom while the electricians downed their tools.

‘That’s a little bit eccentric, mate,’ said the chief electrician.

‘It’s his birthday,’ Emily explained, as if I was five years old.

We sat on the mattress for a while, staring at the skeleton, my sole contribution to the house’s renovation thus far. What we lacked in terms of beds, curtains and cooking equipment we had more than made up for with fake dinosaur remains. I could hear the workmen laughing outside. Fuck it. Let them judge. I didn’t care. But to get back in Emily’s good books I took the girls to the park across the road.

Alexandra Park was an ornate strip of Victoriana designed in the gardenesque style, with all the trimmings. Boating lake. Bandstand. Miniature railway. Streams slaloming between cedars, pines and ashes. There was a playground in the area of park right outside our house, but the girls grew bored of it so I took them grumbling up the hill to the nature reserve, where cormorants fanned their wings in glistening reservoirs and anglers sipped from flasks. Up here was what I’d dubbed the ‘secret playground’. The girls loved this place. Approached from the woods it was as if we’d stumbled on a private paradise of swings, balance beams and slides. But it was an illusion. On the brow behind the playground was a road from which the park was clearly visible to passing drivers. This didn’t matter to the girls. Magic was a point of view. They would always call it the secret playground. The myth was now in their DNA, transmittable down future generations.