9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

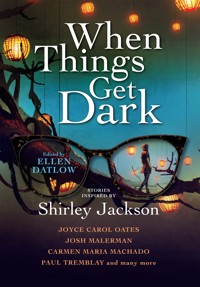

The Stoker Award-winning chilling anthology of 18 short stories in tribute to the genius of Shirley Jackson, collecting today's best horror writers. Featuring Joyce Carol Oates, Josh Malerman, Paul Tremblay, Richard Kadrey, Stephen Graham Jones, Elizabeth Hand and more. A collection of new and exclusive short stories inspired by, and in tribute to, Shirley Jackson. Shirley Jackson is a seminal writer of horror and mystery fiction, whose legacy resonates globally today. Chilling, human, poignant and strange, her stories have inspired a generation of writers and readers. This anthology, edited by legendary horror editor Ellen Datlow, will bring together today's leading horror writers to offer their own personal tribute to the work of Shirley Jackson. Featuring: Joyce Carol Oates Josh Malerman Carmen Maria Machado Paul Tremblay Richard Kadrey Stephen Graham Jones Elizabeth Hand Kelly Link Cassandra Khaw Karen Heuler Benjamin Percy John Langan Laird Barron Jeffrey Ford M. Rickert Seanan McGuire Gemma Files Genevieve Valentine.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction

Funeral Birds | M. Rickert

For Sale By Owner | Elizabeth Hand

In the Deep Woods; The Light is Different There | Seanan McGuire

A Hundred Miles and a Mile | Carmen Maria Machado

Quiet Dead Things | Cassandra Khaw

Something Like Living Creatures | John Langan

Money of the Dead | Karen Heuler

Hag | Benjamin Percy

Take Me, I Am Free | Joyce Carol Oates

A Trip to Paris | Richard Kadrey

The Party | Paul Tremblay

Refinery Road | Stephen Graham Jones

The Door in the Fence | Jeffrey Ford

Pear of Anguish | Gemma Files

Special Meal | Josh Malerman

Sooner or Later, Your Wife Will Drive Home | Genevieve Valentine

Tiptoe | Laird Barron

Skinder’s Veil | Kelly Link

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

About the Editor

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

A Universe of Wishes: A We Need Diverse Books Anthology

Cursed: An Anthology

Dark Cities: All-New Masterpieces of Urban Terror

Dead Letters: An Anthology of the Undelivered, the Missing, the Returned…

Dead Man’s Hand: An Anthology of the Weird West

Exit Wounds

Hex Life

Infinite Stars

Infinite Stars: Dark Frontiers

Invisible Blood

Daggers Drawn

New Fears: New Horror Stories by Masters of the Genre

New Fears 2: Brand New Horror Stories by Masters of the Macabre

Out of the Ruins: The Apocalyptic Anthology

Phantoms: Haunting Tales from the Masters of the Genre

Rogues

Vampires Never Get Old

Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands 2: More Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands: The New Apocalypse

Wonderland: An Anthology

Escape Pod: The Science Fiction Anthology

Dark Detectives: An Anthology of Supernatural Mysteries

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

When Things Get Dark

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781789097153

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789097160

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Introduction © Ellen Datlow 2021

Funeral Birds © M. Rickert 2021

For Sale By Owner © Elizabeth Hand 2021

In the Deep Woods; The Light is Different There © Seanan McGuire 2021

A Hundred Miles and a Mile © Carmen Maria Machado 2021

Quiet Dead Things © Cassandra Khaw 2021

Something Like Living Creatures © John Langan 2021

Money of the Dead © Karen Heuler 2021

Hag © Benjamin Percy 2021

Take Me, I Am Free © Joyce Carol Oates 2021

A Trip to Paris © Richard Kadrey 2021

The Party © Paul Tremblay 2021

Refinery Road © Stephen Graham Jones 2021

The Door in the Fence © Jeffrey Ford 2021

Pear of Anguish © Gemma Files 2021

Special Meal © Josh Malerman 2021

Sooner or Later, Your Wife Will Drive Home © Genevieve Valentine 2021

Tiptoe © Laird Barron 2021

Skinder’s Veil © Kelly Link 2021

The authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of their work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

This book is for my mother, Doris LeibowitzDatlow, who let me read whatever I choseto while growing up. Thanks, mom.

Introduction

I’VE been a fan of Shirley Jackson’s work since I read We Have Always Lived in the Castle as a pre-teen. My appreciation of her uncanny fiction perfectly dovetailed with my love of Ray Bradbury, Harlan Ellison, and so many other writers of weird, fantastic, and horrific literature.

July 2019, I attended Readercon, a literary sf/f convention outside of Boston, and got into a discussion about literary influences. Because the Shirley Jackson Awards are given out at Readercon, Jackson’s name of course came up, and it occurred to me to edit an anthology of stories influenced by her work—but I never followed through.

Until… a few months later, I met a Titan editor at the World Science Fiction convention in Dublin. Although our initial conversation was about anthologies in general, by November—out of the blue—he and his colleagues suggested I edit an anthology of stories influenced by Jackson. So of course I said yes.

I’ve come to realize that Jackson’s influence has filtered—consciously or subconsciously—into the work of many contemporary fantasy, dark fantasy, and horror writers. Some more obviously than others, so they were the writers I initially approached for submissions. Then other writers, writers I would not have pegged as being influenced by her, surprised me with their interest in contributing to such a book.

What is a Shirley Jackson story? She wrote the charming fictionalized memoir Life Among the Savage, a series of collected stories originally published in women’s magazines about her family, living in domestic chaos in rural Vermont. But what sticks in most readers’ minds today is her uncanny work such as “The Lottery,” The Haunting of Hill House, and We Have Always Lived in the Castle. The brilliant 1963 movie The Haunting, based on The Haunting of Hill House, brought Jackson a whole new audience.

Her stories, mostly taking place in mid-twentieth-century America, are filled with hauntings, dysfunctional families and domestic pain; simmering rage, loneliness, suspicion of outsiders; sibling rivalry and women trapped psychologically and/or by the supernatural. They explore the dark undercurrent of suburban life during that time period.

For this anthology, I did not want stories riffing on Jackson’s own. I did not want stories about her or her life. What I wanted was for the contributors to distill the essence of Jackson’s work into their own work, to reflect her sensibility. To embrace the strange and the dark underneath placid exteriors. There’s a comfort in ritual and rules, even while those rules may constrict the self so much that those who must follow them can slip into madness.

To, as Jackson said, “use fear, to take it and comprehend it and make it work.”

And this is what the contributors have done.

Some of the stories herein take place—or end up—in that most domestic of rooms, the dining room, and they center on meals.

Others feature uncanny encounters with ghosts or the inexplicable: misfits finding comfort in one another despite the inevitable destruction their relationship engenders on themselves and others outside their circle of safety; family members turning on each other; women trapped by expectations; people punished for being outside the norm.

So here for your enjoyment are stories that I believe provide the flavor of some of Shirley Jackson’s best fiction. And I would like to think that Jackson, were she still alive, might recognize and appreciate what she birthed.

Funeral Birds

M. Rickert

LENORE had carefully chosen what to wear but felt dissatisfied. She always wanted to be a woman who appeared chic and vaguely kick-ass in black when, in fact, she looked like a half-plucked crow. She reached back to pull down the difficult zipper then drew the dress overhead, momentarily trapped, inhaling the unpleasant scent of her body odor until, with a gasp, she was free, her hair risen in static revolt as she spun on her stockinged feet to the closet. Panic rising, she reached for the hibiscus dress, but what would they think about a woman who arrived late to a funeral in luau attire? She chose the periwinkle instead. The elastic around the waist had grown tight in recent years and the out-of-date Peter Pan collar was much too young for her, but she loved the pattern of demure blue flowers scattered across a cream background. It had been the first thing she bought after her husband died all those years ago. When she wore it she liked to imagine someone had thrown flowers in celebration of her independence, as a counterpoint to the ridiculous rice that had marked the wedding and caused a bird to peck at her head as if trying to drill some sense into her.

Wondering if she would ever like herself again, she fixed her lipstick, brushed her hair, and slipped into the black heels she’d purchased special for the occasion, hoping that, in the right light, they might look dark blue. She dumped the contents from the black purse into her everyday bag. It was beige with brown trim, a gold clasp, and very serviceable. When she finally left, ten minutes later than targeted, she told herself everything would be all right.

“You. Can. Do. This,” she said in the car, flicking the radio on and almost ruining everything by arriving with her windows down, Van Halen blaring loud enough for several mourners standing at the church door to turn around and look.

* * *

It wasn’t until after the long service (why did Lenore always forget how Catholics droned on?) when the priest stepped in front of the altar to relay the family’s invitation to the congregation that she remembered the tuna casserole forgotten in her refrigerator. Under other circumstances this mistake might have caused her to feel defeated, but by that point her spirit was quite elevated. Lenore hadn’t realized how much she dreaded seeing the casket until she discovered there was none. A simple wooden crate the size of a tissue box rested on a pedestal in the nave. Delores had been cremated.

One of Lenore’s favorite things about funerals was the gathering afterward, sometimes spent in church basements but often at a relative’s house, eating potato salad and pickles and pastries all off the same plate. She enjoyed finding a quiet place to sit, listening to the murmured voices, pretending it was her house, and her suffering. The usual price of admission for such solace was attendance at the burial, but Delores’s daughter had other plans for her mother’s ashes, which suited Lenore just fine.

The daughter’s house was a brick bungalow with a suspiciously tidy garden, likely managed by a landscaper. Lenore sat in the car for a few minutes, watching, but while an occasional person arrived with a covered dish or casserole, many did not. She used the rearview mirror to examine her lips, which always failed to please under close inspection. What was it Delores had said? “You don’t look like someone who could keep a secret,” and then Lenore had said, “Well, neither do you.”

“I can keep a secret,” Lenore whispered to the hot air in the car. She was never sure what happened after death, but suspected it wasn’t the end of everything. “I hope you know,” she added, just in case, “friendship never dies.”

She opened the car door, sucking in the fresh air like a person coming out of sedation. She did not lock it. Anyone could tell it wasn’t necessary in that neighborhood; besides, people would be coming and going for a while, though, coincidentally, she walked alone up to the house, the click of her heels like the tap of an insistent woodpecker ricocheting off the trees, picket fence, and stone walls of suburbia.

* * *

When she stepped from the dark foyer through the cozy living room populated by mourners into the dining room with its resplendent spread of glistening strawberries and green salad in glass bowls, assorted cheeses and chocolate cake arranged on pretty china atop a lace tablecloth, Delores’s daughter (wearing a figure-flattering dress the color of eggplant) stopped in mid-sentence, eyes wide, to gasp Lenore’s name, and she was sure she’d made a terrible mistake, misjudged the situation entirely, but the woman walked over to grasp the hands Lenore extended in defensive reflex.

“I’m so glad you came. I want to thank you for everything you did for my mother.”

“Jane,” Lenore began, embarrassed. Clearly others were listening but pretending they weren’t, the conversational hum reduced to a false tenor.

“Jean.”

“I’m sorry.”

Jean was one of those close talkers, moving in so near to Lenore she worried about her own breath and the onions in her morning omelet.

“I heard you’d been at the church. I hoped you would come.”

Lenore glanced away from Jean’s earnest blue eyes (quite like her mother’s) to survey the room. Who? Who reported her attendance? She didn’t know any of these people. Only one stunning woman with severely dark hair and brutal red lips was dressed in black and, judging by how well it suited her, probably owned no other color. No, it wasn’t the fact that Lenore hadn’t worn the funeral dress that set her apart. It was something else. An aspect she recognized from other occasions but never knew how to remedy. The others looked like they lived in the same country where she was merely a tourist.

“It gives me such comfort to know she had you as a nurse.”

“Home health care aid,” Lenore said, squeezing Jean’s hands slightly, which prompted release.

“Excuse me?”

“I’m not a nurse.”

Jean cocked her head slightly.

Like a bird with a worm, Lenore thought. “I’m sorry,” she began, interrupted by a large woman who reminded her of Julia Child stepping between them to offer condolences. After a few awkward moments of being ignored, Lenore backed away to pick up a plate from the table she strived to circle with an air of polite engagement. In reality, she felt a holiday level of excitement at all the food before her, pleased she’d forgotten the tuna casserole, which would have looked out of place, like cat food amongst the splendor.

Lenore, paper plate in one hand and wine glass in the other, meandered through the living room, a small TV room, and a very nice kitchen remodeled in silver and white, almost blinding after all the wood. She was just about to perch on the window seat, vacated as she watched, when she noticed another door, down a narrow hallway past the bathroom. The closed door did not suggest invitation but Lenore was not deterred. After all, she was used to breaching private spaces in her work.

An office: desk and chair faced into the room framed by a large window, the kind with glass panes divided by wood as throughout the rest of the house, though this was probably modern. A little addition, Lenore guessed; nicely done.

She set plate and wine glass on a table beside the large upholstered chair in the corner. There were many lovely elements in the room. A lamp with Tiffany-inspired shade, a large rainbow-colored paperweight on the desk (which Lenore intended to investigate once she finished eating), a few baubles on the shelves propped in front of the books: a blue glass bird, a shape carved in wood—vaguely suggestive of the female form—a rock.

The hydrangeas in bloom beyond the window had attracted several butterflies and Lenore found herself torn, while she ate, between staring dreamily at them or studying the cozy furnishings around her when the door suddenly opened and the daughter stepped into the room, her features—in profile—sharp. Lenore made a little clearing-throat noise and Jean turned, hand over her heart.

“My God,” she said.

“Sorry,” said Lenore. “I just—”

“Oh, no need to apologize.” Jean swatted the air. “I didn’t realize you were in here. These are such tedious events. I’m sure you attend far too many.”

“Well…” Lenore decided not to explain. The truth was she rarely went to the funerals. Delores was special.

“Actually,” Jean said, “this might be divine intervention. Do you believe in that sort of thing?”

Lenore shrugged. She’d learned long ago it was best not to engage in theological speculation. Jean, not bothering to wait for an answer, walked over to the only other chair in the room. It was on wheels, yet difficult to maneuver through the tight space between desk and wall. Watching her struggle, Lenore wondered if she should offer to help, annoyed to think of having to do so on her day off. At just that moment, however, Jean managed to free the chair, which she pushed across the carpet to position in front of Lenore, successfully blocking her only avenue of escape.

“I was hoping we could talk.”

Lenore, who had the wine glass poised at her lips, took a long last gulp, thereby covering much of her expression, buying a little time to think before she set the glass on the table, then picked it up to place a napkin there as a coaster though she saw a ring had already formed. She hated how easily she ruined everything and, turning to face Jean, fully expected to be confronted with a scowl. But the woman lifted her hands as if to reach across the space between them, though they simply hovered in the air before landing in her lap like baby birds unaccustomed to flight.

“I want to ask you about my mother’s last day. Was she at peace? You can tell me the truth. I can take it,” she said, her incongruous smile suggesting she could not.

“Delores and I developed a friendship.”

“How nice,” Jean said, then pursed her lips.

“It was an ordinary day. She went down for her nap and I took out the garbage and when I got back I looked in on her and she was dead.”

“Just like that?”

For a brief moment the memory fluttered. Like one of those beetles you think you squashed but didn’t. Delores struggling against the pillow, her arms flailing, the noises she made.

“My mother was not an easy woman,” Jean said. “You don’t have to pretend otherwise. I’m glad she had your company. But I know how difficult she could be.”

“No, really. We were friends.”

Jean stood up and began pushing the chair across the carpet.

Lenore had not realized she’d been holding her breath until, exhaling in relief, her ribs pressed against the confined elastic of the dress and she felt a button pop at the back.

With a grunt of annoyance, Jean abandoned the uncooperative chair to walk around the desk where she opened a drawer, removing what looked like a checkbook.

“This is just a small token,” she said, not looking up while she wrote.

“Oh, no,” said Lenore, horrified.

“Nonsense. I know how hard you people work,” Jean said, walking briskly back to Lenore. “Take it. Buy yourself something nice.”

Her glance might have lingered just a little too long on Lenore’s dress. The woman had no way of knowing, of course, but Lenore felt like the exchange was vile, as though she were some kind of hired killer.

Jean bent her knees slightly to place the check in Lenore’s lap, amongst the primroses. “I’m so glad we had this time to talk. I wish I could just hide in here with you,” she said.

“Yes, of course,” said Lenore.

“Stay as long as you like, but close the door tightly when you leave. Guests really aren’t supposed to be in here.”

Lenore kept her expression placid as she nodded, though she did understand she was being reprimanded. She didn’t allow herself to smile until she was alone again, looking at the amount written on the check before tucking it into her purse. She stood up and tossed the paper plate with blobs and smears of food on it into the small trashcan beside the desk, but left the wine glass on the table.

As if her hand worked without any direction from her mind, it plucked the glass bird from the bookshelf as she passed, dropped it into her bag, then closed the gold clasp.

The party had diminished quite a bit during Lenore’s little break, making her presence more obvious, yet she passed through the rooms like a ghost, unhindered by anyone. Sometimes when she had that effect on others it bothered her, but this time it made her feel powerful.

* * *

Lenore frowned as she parked in front of her place. It was one apartment in a building of four she had been proud to call home for nearly a decade. What difference did it make that there were no hydrangeas outside her window?

She hurried up the walk, in case anyone might be watching and notice how her dress gaped at the back where the button had popped. As soon as she stepped inside she locked the door and kicked off her shoes. They were too tight. It would take a few more wears for them to fit comfortably. She strained to unbutton the dress, and heard it rip before she stepped out of it. She would buy a new one, she thought as she walked down the hall to draw a bath, pouring into the stream a packet of lavender bubble powder one of her clients (not Delores) had given her in a Christmas basket the previous December. While the water ran, she took the tuna casserole out of the refrigerator and put it in the oven. She really hadn’t eaten that much, and figured she’d be hungry soon enough.

She opened the purse, reaching inside for the bird made of blue glass, which fit in the palm of her hand. Lovely. One of the nicest things she owned. It deserved a position of honor, not to be stuffed on some shelf. She surveyed her living space from the other side of the breakfast counter she rarely sat at, the stools most often used as dumping grounds. After the daughter’s lovely house, the small living room furnished with used pieces Lenore found by the side of the road, or purchased secondhand, seemed bleak.

She placed the bird on the coffee table in front of the sagging couch, then hurried back to the bathroom, arriving in time to turn the water off before causing a flood. She took a long soak until the scent of tuna noodle casserole overpowered the lavender, and her stomach growled.

“Maybe I’ll get a new robe,” she said, wrapping herself in the old terry cloth one she’d owned for years.

She ate her supper on the couch, only half paying attention to the real housewives on TV, fighting again. The glass bird was so pretty it shamed everything else.

“Maybe I’ll buy a new table. And a lamp,” she said. “I liked your daughter’s lamp.”

Lenore fell asleep on the couch, as sometimes happened, awoken by a loud commercial for a frying pan. She shut the TV off but left the light on, as was her practice, to deter any intruder. Once in bed she wondered if she might spend the money on a new mattress, which would be wise if not particularly exciting, debating this until she fell asleep for an indeterminate amount of time before being aroused by the noxious aroma of tuna noodle casserole mingled with lavender. Lenore had always been sensitive to strong odors.

Thinking she would turn the stove fan on, she padded to the kitchen, stopping in her tracks when she saw the back of Delores’s head. Dead Delores. Cremated Delores. Sitting on the couch.

Lenore walked slowly, pausing on her way to grab the tea kettle from the stove, only then noticing the casserole on the counter. She could have sworn she put it away, though clearly she hadn’t.

“Not sure what you plan to do with that kettle. I’m already dead,” said Delores, sitting with a bowl of tuna noodle casserole in her lap.

“What are you doing here?” Lenore asked.

Delores gave her one of her looks. The one that meant “I’m just going to pretend I don’t notice you being stupid,” as she stabbed chunks of tuna noodle casserole with her fork. “Sit down, Lenore.”

Lenore did as she was told, backing into the chair she’d purchased from Goodwill a few years before. It had only been ten dollars, but was so uncomfortable she rarely sat in it.

“Why are you here?”

“I think you know the answer,” Delores said, drawing fork to her mouth and chewing, though, after a while, unmasticated tuna and noodles dropped out. “Ah shit,” she said.

“Do you need help?”

“You know you’re stuck with me now, don’t you?” Delores asked, making another stab at the bowl in her lap.

“You should go to the light,” said Lenore.

Delores snorted. A noodle flew from her mouth and landed on the coffee table beside the glass bird.

“So, I guess this makes you a serial murderer.”

“No it doesn’t,” Lenore said, insulted.

“Yeah. It does. You killed your husband and then you killed me.”

“Twenty years apart,” Lenore said. “And I only killed you cause you promised not to tell anyone about it. I thought we were sharing secrets. I thought you were my friend.”

“I thought you were my friend!” Delores shouted. “Who did I tell? I told no one. And this is the thanks I get.”

“I saw how you looked at me.”

“Give me a break. Can’t a person be surprised?”

“You were going to tell someone.”

“Was not.”

“Don’t lie, Delores.”

“Your tuna noodle casserole tastes like piss.”

“Well, that’s cause you’re dead. You aren’t even chewing right.”

Delores looked at the bowl in her lap and laughed. It was a quick bark of a sound, slightly feral, quite different from when she was alive.

“Please,” Lenore said. “Try to understand my position.”

Delores glared at Lenore.

“You should buy that new mattress,” she said. “And probably a bigger bed. Cause I’m not going anywhere without you.”

Lenore, who would not have believed it possible of herself (because she was not a psychopath), leapt from her chair to swing the tea kettle in a wide arc at the old woman’s head. Though she couldn’t have felt a thing—she was dead, after all—she looked up at Lenore with horror, raising her bony arms to block the blow. There was no blood, and no impact. In frustration, Lenore slammed the kettle down, shattering the glass bird.

She stared at it and tried not to cry.

“You know what I just remembered?” Dolores asked. “In all the excitement I never got to tell you my best secret.”

“Oh. Right,” said Lenore. “That’s why you’re here.”

“Yep. I came all the way from heaven to help you.”

“To help me?”

“That’s right, Lenore. Cause your tuna noodle casserole tastes like shit.”

“Oh, for God’s sake, Delores—”

“You need to put some crunch into it.”

“You mean potato chips? I already know about that, Delores. Everyone knows about that. I just forget to buy them. Okay? You can go now.”

“Not potato chips. Broken glass. Like what you got right there. You just try it and see. We learn about this stuff after being dead. I know things now.”

“That’s ridiculous. Don’t be ridiculous,” Lenore said, but she carefully swept the shards into an empty pickle jar, which she set in the cupboard beside the salt and pepper shakers, the lid closed tight, turning around to discover that Delores had disappeared; gone back to heaven or hell, or the little box her daughter had put her in. Lenore sealed the aluminum foil over the remains of the casserole, which she placed in the refrigerator, checked that the front door was locked, and went to bed, tossing and turning throughout the night.

In the morning she called the agency to tell them she was sick then drove to the mattress store, where she chose a comfortable queen-sized mattress, and a new bed frame. But, of course, as Lenore was well aware, any solution creates new problems: she needed queen-sized sheets and comforter as well. On the way home from the mall, she stopped at the market for noodles and canned tuna. A woman stared at Lenore as she loaded her cart and said, “Looks like someone has a craving for tuna noodle casserole. Don’t forget the chips,” and the checkout lady said something snide about how much tuna could one person eat, but Lenore ignored both of them. She wasn’t sure what had gotten into her, but she felt free in a way she hadn’t since buying the primrose dress all those years ago, no longer interested in accommodating everyone else’s preferences or fighting her own unreasonable impulses. If she wanted to eat tuna noodle casserole every night for the rest of her life, she would. Groceries loaded in her car, she paused in the parking lot to stare at a flock of birds circling overhead, so distant she could not identify them.

For Sale by Owner

Elizabeth Hand

ICAN’T remember exactly when I first started entering houses while the owners weren’t around. Before my children were born, so that’s at least thirty-five years ago. It started in the fall, when I used to walk my old English sheepdog, Winston, down one of the camp roads on Taylor Pond. That road is more built up now with new summer houses and even a few year-round homes, but back then there were only two houses that were occupied all year. The rest, maybe a dozen all together, were camps or cottages, uninsulated and very small, certainly by today’s standards. They straggled along the lakefront, some in precarious stages of decay, the others neatly kept up with shingles or board-and-batten siding. These days you couldn’t build a structure that close to the waterfront, but eighty or ninety years ago, no one cared about things like that.

Anyway, Winston and I would amble along the dirt road for an hour or two at a time, me kicking at leaves, Winston snuffling at chipmunks and red squirrels. This would be after I got off work at the CPA office where I answered the phone, or on weekends. The pond was beautiful—a lake, really, they just called it a pond—and sometimes I’d watch loons or otters in the water, or a bald eagle overhead. I never saw another living soul except for Winston. No cars ever went by— those two year-round homes were at the head of the road.

I’m not sure why I decided one day just to walk up to one of the camps and see if the door was open. Probably I was looking at the water, and the screened-in porch, and got curious about who lived inside. Although to be honest, I really wasn’t interested in who lived there. I just wanted to see what the inside looked like.

I tried the screen door. It opened, of course—who locks their screen door? Then I tried the knob on the inner door and it opened, too. I told Winston to wait for me, and went inside.

It looked pretty much like any camp does, or did. Small rooms, knotty pine walls, exposed beams. One story, with a tiny bathroom and a metal shower stall. Tiny kitchen with a General Electric fridge that must’ve dated to the early 1960s, its door held open by a dishrag wrapped around the handle. Two small bedrooms with two beds apiece.

The living room was the nicest, with big old mullioned windows, a door that opened onto the screened porch. The kind of furniture you find in camps—secondhand stuff, or chairs and side tables demoted from the primary residence. A big coffee table; shelves holding boxes of games and puzzles, paperbacks that had swollen with damp. Stone fireplace with a small pile of camp wood beside it. On the walls, framed Venus paint-by-numbers paintings of deer or mountains.

Camps had a particular smell in those days. Maybe they still do. Mildew, coffee, cigarette smoke, woodsmoke, Comet. It’s a nice smell, even the mildew if it’s not too strong. I spent a minute or two gazing at the lake through the windows. Then I left.

The next camp was pretty much the same thing, though with two canoes by the water instead of one, the dock pulled out alongside them. The door was unlocked. There were more games here, also a wrapped-up volleyball net and a plastic Whiffle Ball bat. Children’s bathing suits hanging in the bathroom. Nicer furniture, scuffed up but newer-looking, blond wood. The chairs and table and couch looked like they’d been bought as a set. The view here wasn’t as open as at the first house, because some tamaracks had grown too close to the windows. But it was still nice, with the children’s artwork displayed on the walls, and a framed photograph of Mount Cadillac.

I made sure the door closed securely behind me and continued walking. Winston stopped chasing squirrels and seemed content to stay beside me. I idly plucked leaves and sticks from his tangled fur, making a mental note to give him a thorough brushing when I got home, maybe a bath.

For the next hour or so it was more of the same. Only about half of the camps were unlocked, though all the screened porch doors were open. In those cases, I’d check out the view from the porch, angling among stacked-up wicker or plastic furniture, folded lawn chairs, life preservers and deflated water toys. On one porch, the door to the living room was open, so I got to take a look at that.

There was a pleasant sameness to the decor of all these places, if you could call it decor, and an even more reassuring sense of difference between how people spruced up their little havens. A tiny, handmade camp that consisted of only a single room had fishing gear in the corner, a huge moose rack over the door, and a six-point deer rack on the outhouse. In the neighboring shingle cottage, almost every surface was covered by something crocheted or handwoven or knit or quilted, and the air smelled strongly of cigarettes and potpourri.

I took stock of each place, and considered how I might move around the furniture, or what trees I’d cut down. Once or twice I recognized the name on the door, or a face in a faded family photograph. I never opened any drawers or cabinets or took anything. I wouldn’t have dreamed of that. Like I said, I just wanted to see what they looked like inside.

Finally, we reached the end of the camp road. Winston was tired and the sun was getting low, besides which I never walked any farther than this. So we turned round and walked back to the head of the camp road, then onto the paved road, where I’d left my old Volvo parked on the grass. Winston hopped into the back and we went home. I spent about an hour brushing him but didn’t bother with the bath. He really hated baths.

For the rest of that autumn, I’d occasionally walk along different camp roads in town and do the same thing. By the time Thanksgiving arrived, my curiosity had been sated. As the days grew darker and colder, I walked Winston close to home. A year later I married Brandon, and a year after that our daughter was born.

By the time I started walking again, a decade had passed. The old dog had died, and we never got another. I walked with other women now, the mothers of my children’s classmates. I grew close to one in particular, Rose. We began walking when our boys were nine or ten years old, and continued doing so for almost thirty years. Like me, Rose liked to walk along the camp roads, where there were few cars, though in summer the mosquitoes were terrible, and over the decades we learned to be increasingly mindful of ticks.

Rose was small and cheerful and talked a lot. Local gossip, family news. Sometimes we’d rant about politics. Our friend Helen joined us occasionally. She walked faster than Rose and I, so there’d be less conversation when the three of us were together. Over the years, Rose, like me, had stopped coloring her hair. I went mousy grey but Rose’s grew in the color of a new nickel. Helen continued to dye her hair, though it wasn’t as blond as it had been. Our husbands were all friendly, and the six of us often got together for dinners or bonfires or the Super Bowl.

So it was odd that I had known Rose for almost a quarter century before I learned that she, too, liked exploring empty houses. We were walking on the dirt road that runs along Lagawala Lake. It was late fall, and the weather had been unseasonably cold for about a week. There were few houses along the camp road, all clustered at the far end, all vacated till the following summer—we knew that because we’d gotten in the habit of peering through the windows. I never mentioned my old habit, though once or twice, when Rose wasn’t looking, I’d test the door of a cottage. But everyone kept their houses locked now.

About halfway down the road someone from out of state had bought a huge parcel of the lakefront, where for the last ten years they’d been building a vast compound. We both knew some of the contractors who’d worked there at some point—stonemasons, builders, roofers, electricians, plumbers, heating and cooling experts, carpenters—and they told us what was inside the various Shingle-style mansions and outbuildings that had been erected. An indoor swimming pool, a billiards room, a separate building devoted to a screening room with a bar designed to look like an English pub. A miniature golf course with bronze statues at every hole. The caretaker had his own Craftsman cottage, bigger than my house.

Most extravagant of all was an outdoor carousel housed in its own building. Electronically controlled curtains kept us from ever being able to see what this looked like inside. There was also a hideous, two-story high, blaze-orange cast-resin sculpture of a plastic duck. In nearly a decade, we never saw any sign that someone had occupied the house or property, other than the caretaker.

One winter day early in the construction, when the mansion had been closed in and roofed but none of the interior work had been done, Rose and I halted to stare up at it. Work had stopped for the winter.

“That is a disgusting waste of money,” I said.

“You’re not kidding. They’re heating it, too.”

“Heating it? The windows aren’t even in.”

“I know. But the heat’s blasting inside.”

“How do you know?”

“Cause I’ve been in a bunch of times. The doors are all open. Want to see?”

I glanced down the road, toward the caretaker’s house. A thick stand of evergreens screened us from it. Besides, if anyone caught us, what would they do? We were two respectable middle-aged ladies who’d served on town committees and contributed to dozens of bake sales.

“Sure,” I said, and we went inside.

It was warm as a hotel room in there. Tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of tools and materials had been left in the various rooms— electrical wiring, sheetrock, tools, shopvacs, you name it. We wandered around for a while, but I lost interest fairly quickly. There were no furnishings, and the lake view was nice but not spectacular. I also wondered if the owners had installed some kind of security system.

“We better go,” I said. “They might have CCTV or something.”

Rose shrugged. “Yeah, okay. But it’s fun, isn’t it?”

“Yeah,” I said, and we returned to the road. After few seconds I added, “I used to do that sometimes, on the camp roads. Go into houses when no one was there.”

“No!” Rose exclaimed so loudly that at first I thought she was horrified. “Me too! For years.”

“Really?”

“Sure. No one ever used to lock their doors. It was fun. I never did anything.”

“Me neither.”

After that, we’d compare notes whenever we passed a house we had entered. Rose knew more about the owners than I did, but then she knew more people in town than me. Sometimes, when Helen walked with us, we’d forget and mention a camp we’d both been inside.

“How do you know these people?” Helen asked me.

“I don’t,” I said. “I just like looking in their windows.”

“Me too,” said Rose.

Last October, the three of us took a long afternoon walk, not on one of the camp roads but a sparsely populated paved road that runs from our village center up the neighboring mountainside. We call it Mount Kilden; it’s actually a hill. We drove in my car to where there’s a pull-out and parked, then started to walk. Helen with her long legs strode a good ten feet in front of Rose and me, and looked over her shoulder to shout her contributions to our conversation.

“If you want to talk you’re going to have to slow down,” I finally yelled.

Helen halted, shaking her head. “You both should walk with Tim— I have to run to keep up with him.”

I said, “If I ran I’d have a heart attack.”

Helen laughed. “Good thing I know CPR,” she said, and once more started walking like she was in a race.

The paved road up Mount Kilden runs for about four miles, then does a dogleg and turns into an old gravel road that continues for another mile or two before it ends abruptly in a pull-out surrounded by towering pines. A rough trail ran from the pull-out to the top of Mount Kilden, with a spectacular view of the lakes, Agganangatt River, and the real mountains to the north. The trail was used by locals who made a point of not telling people from away about it. It had been a decade since I’d walked that path.

A hundred and fifty years ago, most of this was farmland, including a blueberry barren. Now woodland has overtaken the fields: tall maples and oaks, birch and beech, white pine, hemlock, impassable thorny blackberry vines. The autumn leaves were at their peak, gold and scarlet and yellow against a sky so blue it made my eyes hurt. Goldenrod and aster and Queen Anne’s lace bloomed along the side of the road. Somewhere far away a dog barked, but up here you couldn’t hear a single car. Our pace had slackened, and even Helen slowed to admire the trees.

“It’s so beautiful up here,” she said. “We should walk here more often. Why don’t we walk here more often?”

I groaned. “Maybe because I’d have a heart attack every time we did?”

“We can go back if you want,” said Rose, and patted my arm.

“No, I’m fine. I’ll just walk slowly.”

Within a few minutes, we all started to walk more slowly. The woods had retreated from the road here: we could see more sky, which gave the impression we were much higher than we really were. Old stone walls snaked among the trees, marking boundaries between farms and homesteads that had long since disappeared. Nothing remained of the houses except for cellar holes, and the trees that had been planted by their front doors—always a pair, one lilac and one apple tree, the lilacs now forming dense stands of grey and withered green, the apple trees still bearing fruit.

I picked one. It tasted sweet and slightly winey—a cider apple. I finished it and tossed the core into the woods, and hurried after the others.

“Look,” said Helen, pointing to where the trees thinned out ever more, just past a curve in the dirt road. “Don’t you love that house? When Tim and I used to hike up here, we always said we’d buy it and live there someday.”

“We did too!” exclaimed Rose in delight. “Hank loved that house. I loved that house.”

They both glanced at me, and I nodded. “I never came here with Brandon, but oh yes. It’s a beautiful house.”

Laughing, Rose broke into an almost-run. Helen followed and quickly passed her. After a minute or two, I caught up with them.

A broad lawn swept down to the road. The grass looked like it hadn’t been mowed in a few weeks, but it hadn’t been neglected to the point where weeds or saplings had taken root. Brilliant crimson leaves carpeted it, from an immense maple tree that towered in the middle of the lawn. Thirty or so feet behind the tree stood a house. Not an old farmhouse or Cape Cod, which you’d expect to find here, and not a Carpenter Gothic, either. This was a Federal-style house, almost square and two stories tall, with lots of big windows, white clapboard siding, and two brick chimneys. You don’t see a whole lot of Federal houses in this area, and I’d guess this one was built in the early 1800s. There was no sign of a barn or other outbuildings. No garage, though that’s not so unusual. We don’t have a garage, either. Blue and purple asters grew along its front walls, and the tall grey stalks of daylilies that had gone by.

The house appeared vacant—no curtains in the windows, no lights— but it had been kept up. The white paint was weathered but not too bad. The granite foundation hadn’t settled. The chimneys were intact and didn’t seem in need of repointing. I walked up to the front door and tried the knob.

It turned easily in my hand. I looked back to catch Rose’s eye, but she was heading around the side of the house. A moment later I heard her cry out.

“Marianne, look!”

I left the door and walked to the side of the house, where Rose pointed at a sign leaning against the wall.

FOR SALE BY OWNER.

“It’s for sale,” she said, almost reverently.

“It was for sale.” Helen picked up the sign and hefted it—handmade of plywood painted white and nailed to a stake. “They probably took it off the market after Labor Day.”

I stepped closer to examine it. The words FOR SALE BY OWNER were neatly painted in black letters. Beneath, someone had scrawled a phone number in Magic Marker. The numbers had blurred together from the rain. I didn’t recognize the area code.

“I wonder what they’re asking for it,” said Helen, and leaned the sign back against the house.

“A lot,” I said. Real estate here has gone through the roof in the last ten years.

“Well, I don’t know.” Rose stepped back and stared up at the roofline, straight as though drawn by a ruler on the sky. “It’s kind of far from everything.”

“There is no ‘far from anything’ in this town,” I retorted. “And people who move here, they want privacy.”

“Then why hasn’t it sold?”

“If the owner’s selling it, it might not be listed anywhere. Nobody drives up here except locals. And the season’s over, it’s off the market now anyway. That’s why they took down the sign.” I gestured to the front of the house. “The door’s open. Want to look inside?”

“Of course,” said Rose, and grinned.

Helen frowned. “That’s trespassing.”

“Only if we get caught,” I replied.

We headed to the front door. I pushed it open and we went inside, entering a small anteroom that would be a mudroom if anyone lived there, and cluttered with boots and coats and gear. Now it was empty and spotless. We stepped cautiously through another doorway, into what must have been the living room.

“Wow.” Rose’s eyes widened. “Look at this.”

I blinked, shading my eyes. Bright as it had been outside, here it was even brighter. Sunlight streamed through the large windows. The hardwood floors were so highly polished they looked as though someone had spilled maple syrup on them. The ceiling was high, the walls unadorned with moldings or wainscoting, and painted white. I walked to one wall and laid my hand against it, the surface smooth and slightly warm to the touch. I rapped it gently with my knuckles. Plaster, not drywall, and smooth as a piece of glass. Not what I’d expect to find in a house this old, where the plaster should be cracked or pitted. It must have been refinished not long ago.

I turned to Rose and Helen. “Someone’s spent a lot of money here.”

“It doesn’t look like anyone’s ever been here,” replied Helen. She was crouched in one corner. “Not for ages. Look—this is the only electrical outlet in this room, and it must be almost a hundred years old.”

Helen and Rose wandered off. I could hear them laughing and exclaiming in amazement at what they found: an old-fashioned hand pump in the kitchen sink, water closet rather than a modern toilet. I stayed in the living room, enchanted by the light, which had an odd clarity. An empty room in a house this old should be filled with dust motes, but the sun pouring through the windows appeared almost solid. You hear about golden sunlight: this really did look solid, so much so that I took a step into the center of the room and swept my hand through the broad sunbeam that bisected the empty space. I felt nothing except a faint warmth.

“We’re going upstairs!” Rose yelled from another room.