Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Tacet Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: 3 books to know

- Sprache: Englisch

Welcome to the3 Books To Knowseries, our idea is to help readers learn about fascinating topics through three essential and relevant books. These carefully selected works can be fiction, non-fiction, historical documents or even biographies. We will always select for you three great works to instigate your mind, this time the topic is:Napoleonic Wars. - The Duel; A Military Tale By Joseph Conrad - The Red and the Black By Sthendal - War and Peace By Leo TolstoyThe Duel is a Conrad's brilliantly ironic tale about two officers in Napoleon's Grand Army who, under a futile pretext, fought an on-going series of duels throughout the Napoleanic Wars. Both satiric and deeply sad, this masterful tale treats both the futility of war and the absurdity of false honor, war's necessary accessory. The Red and the Black is a historical psychological novel in two volumes by Stendhal, published in 1830. It chronicles the attempts of a provincial young man to rise socially beyond his modest upbringing through a combination of talent, hard work, deception, and hypocrisy. He ultimately allows his passions to betray him. War and Peace is a novel by the Russian author Leo Tolstoy. It is regarded as a central work of world literature and one of Tolstoy's finest literary achievements. The novel chronicles the history of the French invasion of Russia and the impact of the Napoleonic era on Tsarist society through the stories of five Russian aristocratic families. This is one of many books in the series 3 Books To Know. If you liked this book, look for the other titles in the series, we are sure you will like some of the topics

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 3934

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title Page

Introduction

Authors

The Duel; A Military Tale

The Red and the Black

War and Peace

About the Publisher

Introduction

WELCOME TO THE 3 Books To Know series, our idea is to help readers learn about fascinating topics through three essential and relevant books.

These carefully selected works can be fiction, non-fiction, historical documents or even biographies.

We will always select for you three great works to instigate your mind, this time the topic is: Napoleonic Wars.

The Duel; A Military Tale By Joseph Conrad

The Red and the Black By Sthendal

War and Peace By Leo Tolstoy

The Duel is a Conrad’s brilliantly ironic tale about two officers in Napoleon’s Grand Army who, under a futile pretext, fought an on-going series of duels throughout the Napoleanic Wars. Over decades, on every occasion they chanced to meet, they fought. Both satiric and deeply sad, this masterful tale treats both the futility of war and the absurdity of false honor, war’s necessary accessory.

The Red and the Black is a historical psychological novel in two volumes by Stendhal, published in 1830. It chronicles the attempts of a provincial young man to rise socially beyond his modest upbringing through a combination of talent, hard work, deception, and hypocrisy. He ultimately allows his passions to betray him. The title is taken to refer to the tension between the clerical (black) and secular (red) interests of the protagonist, but this interpretation is but one of many.

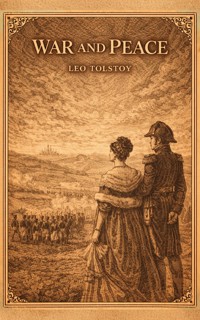

War and Peace is a novel by the Russian author Leo Tolstoy. It is regarded as a central work of world literature and one of Tolstoy's finest literary achievements. The novel chronicles the history of the French invasion of Russia and the impact of the Napoleonic era on Tsarist society through the stories of five Russian aristocratic families. Portions of an earlier version, titled The Year 1805, were serialized in The Russian Messenger from 1865 to 1867. Tolstoy said War and Peace is "not a novel, even less is it a poem, and still less a historical chronicle."

This is one of many books in the series 3 Books To Know. If you liked this book, look for the other titles in the series, we are sure you will like some of the topics

Authors

JOSEPH CONRAD (3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Polish-British writer regarded as one of the greatest novelists to write in the English language. Though he did not speak English fluently until his twenties, he was a master prose stylist who brought a non-English sensibility into English literature. Conrad wrote stories and novels, many with a nautical setting, that depict trials of the human spirit in the midst of what he saw as an impassive, inscrutable universe. Conrad is considered an early modernist, though his works contain elements of 19th-century realism.[3] His narrative style and anti-heroic characters have influenced numerous authors, and many films have been adapted from, or inspired by, his works. Numerous writers and critics have commented that Conrad's fictional works, written largely in the first two decades of the 20th century, seem to have anticipated later world events.

Stendhal, pseudonym of Marie-Henri Beyle, (born January 23, 1783, Grenoble, France—died March 23, 1842, Paris), one of the most original and complex French writers of the first half of the 19th century, chiefly known for his works of fiction. During Stendhal’s lifetime, his reputation was largely based on his books dealing with the arts and with tourism (a term he helped introduce in France), and on his political writings and conversational wit. His unconventional views, his hedonistic inclinations tempered by a capacity for moral and political indignation, his prankish nature and his hatred of boredom—all constituted for his contemporaries a blend of provocative contradictions. But the more authentic Stendhal is to be found elsewhere, and above all in a cluster of favourite ideas: the hostility to the concept of “ideal beauty,” the notion of modernity, and the exaltation of energy, passion, and spontaneity.

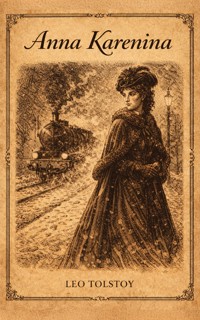

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy (9 September 1828 – 20 November 1910), usually referred to in English as Leo Tolstoy, was a Russian writer who is regarded as one of the greatest authors of all time. He received multiple nominations for Nobel Prize in Literature every year from 1902 to 1906, and nominations for Nobel Peace Prize in 1901, 1902 and 1910, and his miss of the prize is a major Nobel prize controversy. Born to an aristocratic Russian family in 1828, he is best known for the novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina, often cited as pinnacles of realist fiction. Tolstoy's fiction includes dozens of short stories and several novellas such as The Death of Ivan Ilyich, Family Happiness, and Hadji Murad. He also wrote plays and numerous philosophical essays. In the 1870s Tolstoy experienced a profound moral crisis, followed by what he regarded as an equally profound spiritual awakening, as outlined in his non-fiction work A Confession. His literal interpretation of the ethical teachings of Jesus, centering on the Sermon on the Mount, caused him to become a fervent Christian anarchist and pacifist. Tolstoy's ideas on nonviolent resistance, expressed in such works as The Kingdom of God Is Within You, were to have a profound impact on such pivotal 20th-century figures as Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.

The Duel; A Military Tale

BY JOSEPH CONRAD

––––––––

I

––––––––

NAPOLEON I., WHOSE career had the quality of a duel against the whole of Europe, disliked duelling between the officers of his army. The great military emperor was not a swashbuckler, and had little respect for tradition.

Nevertheless, a story of duelling, which became a legend in the army, runs through the epic of imperial wars. To the surprise and admiration of their fellows, two officers, like insane artists trying to gild refined gold or paint the lily, pursued a private contest through the years of universal carnage. They were officers of cavalry, and their connection with the high-spirited but fanciful animal which carries men into battle seems particularly appropriate. It would be difficult to imagine for heroes of this legend two officers of infantry of the line, for example, whose fantasy is tamed by much walking exercise, and whose valour necessarily must be of a more plodding kind. As to gunners or engineers, whose heads are kept cool on a diet of mathematics, it is simply unthinkable.

The names of the two officers were Feraud and D’Hubert, and they were both lieutenants in a regiment of hussars, but not in the same regiment.

Feraud was doing regimental work, but Lieut. D’Hubert had the good fortune to be attached to the person of the general commanding the division, as officier d’ordonnance. It was in Strasbourg, and in this agreeable and important garrison they were enjoying greatly a short interval of peace. They were enjoying it, though both intensely warlike, because it was a sword-sharpening, firelock-cleaning peace, dear to a military heart and undamaging to military prestige, inasmuch that no one believed in its sincerity or duration.

Under those historical circumstances, so favourable to the proper appreciation of military leisure, Lieut. D’Hubert, one fine afternoon, made his way along a quiet street of a cheerful suburb towards Lieut. Feraud’s quarters, which were in a private house with a garden at the back, belonging to an old maiden lady.

His knock at the door was answered instantly by a young maid in Alsatian costume. Her fresh complexion and her long eyelashes, lowered demurely at the sight of the tall officer, caused Lieut. D’Hubert, who was accessible to esthetic impressions, to relax the cold, severe gravity of his face. At the same time he observed that the girl had over her arm a pair of hussar’s breeches, blue with a red stripe.

“Lieut. Feraud in?” he inquired, benevolently.

“Oh, no, sir! He went out at six this morning.”

The pretty maid tried to close the door. Lieut. D’Hubert, opposing this move with gentle firmness, stepped into the ante-room, jingling his spurs.

“Come, my dear! You don’t mean to say he has not been home since six o’clock this morning?”

Saying these words, Lieut. D’Hubert opened without ceremony the door of a room so comfortably and neatly ordered that only from internal evidence in the shape of boots, uniforms, and military accoutrements did he acquire the conviction that it was Lieut. Feraud’s room. And he saw also that Lieut. Feraud was not at home. The truthful maid had followed him, and raised her candid eyes to his face.

“H’m!” said Lieut. D’Hubert, greatly disappointed, for he had already visited all the haunts where a lieutenant of hussars could be found of a fine afternoon. “So he’s out? And do you happen to know, my dear, why he went out at six this morning?”

“No,” she answered, readily. “He came home late last night, and snored. I heard him when I got up at five. Then he dressed himself in his oldest uniform and went out. Service, I suppose.”

“Service? Not a bit of it!” cried Lieut. D’Hubert. “Learn, my angel, that he went out thus early to fight a duel with a civilian.”

She heard this news without a quiver of her dark eyelashes. It was very obvious that the actions of Lieut. Feraud were generally above criticism. She only looked up for a moment in mute surprise, and Lieut. D’Hubert concluded from this absence of emotion that she must have seen Lieut. Feraud since the morning. He looked around the room.

“Come!” he insisted, with confidential familiarity. “He’s perhaps somewhere in the house now?”

She shook her head.

“So much the worse for him!” continued Lieut. D’Hubert, in a tone of anxious conviction. “But he has been home this morning.”

This time the pretty maid nodded slightly.

“He has!” cried Lieut. D’Hubert. “And went out again? What for? Couldn’t he keep quietly indoors! What a lunatic! My dear girl —”

Lieut. D’Hubert’s natural kindness of disposition and strong sense of comradeship helped his powers of observation. He changed his tone to a most insinuating softness, and, gazing at the hussar’s breeches hanging over the arm of the girl, he appealed to the interest she took in Lieut. Feraud’s comfort and happiness. He was pressing and persuasive. He used his eyes, which were kind and fine, with excellent effect. His anxiety to get hold at once of Lieut. Feraud, for Lieut. Feraud’s own good, seemed so genuine that at last it overcame the girl’s unwillingness to speak. Unluckily she had not much to tell. Lieut. Feraud had returned home shortly before ten, had walked straight into his room, and had thrown himself on his bed to resume his slumbers. She had heard him snore rather louder than before far into the afternoon. Then he got up, put on his best uniform, and went out. That was all she knew.

She raised her eyes, and Lieut. D’Hubert stared into them incredulously.

“It’s incredible. Gone parading the town in his best uniform! My dear child, don’t you know he ran that civilian through this morning? Clean through, as you spit a hare.”

The pretty maid heard the gruesome intelligence without any signs of distress. But she pressed her lips together thoughtfully.

“He isn’t parading the town,” she remarked in a low tone. “Far from it.”

“The civilian’s family is making an awful row,” continued Lieut. D’Hubert, pursuing his train of thought. “And the general is very angry. It’s one of the best families in the town. Feraud ought to have kept close at least —”

“What will the general do to him?” inquired the girl, anxiously.

“He won’t have his head cut off, to be sure,” grumbled Lieut. D’Hubert. “His conduct is positively indecent. He’s making no end of trouble for himself by this sort of bravado.”

“But he isn’t parading the town,” the maid insisted in a shy murmur.

“Why, yes! Now I think of it, I haven’t seen him anywhere about. What on earth has he done with himself?”

“He’s gone to pay a call,” suggested the maid, after a moment of silence.

Lieut. D’Hubert started.

“A call! Do you mean a call on a lady? The cheek of the man! And how do you know this, my dear?”

Without concealing her woman’s scorn for the denseness of the masculine mind, the pretty maid reminded him that Lieut. Feraud had arrayed himself in his best uniform before going out. He had also put on his newest dolman, she added, in a tone as if this conversation were getting on her nerves, and turned away brusquely.

Lieut. D’Hubert, without questioning the accuracy of the deduction, did not see that it advanced him much on his official quest. For his quest after Lieut. Feraud had an official character. He did not know any of the women this fellow, who had run a man through in the morning, was likely to visit in the afternoon. The two young men knew each other but slightly. He bit his gloved finger in perplexity.

“Call!” he exclaimed. “Call on the devil!”

The girl, with her back to him, and folding the hussars breeches on a chair, protested with a vexed little laugh:

“Oh, dear, no! On Madame de Lionne.”

Lieut. D’Hubert whistled softly. Madame de Lionne was the wife of a high official who had a well-known salon and some pretensions to sensibility and elegance. The husband was a civilian, and old; but the society of the salon was young and military. Lieut. D’Hubert had whistled, not because the idea of pursuing Lieut. Feraud into that very salon was disagreeable to him, but because, having arrived in Strasbourg only lately, he had not had the time as yet to get an introduction to Madame de Lionne. And what was that swashbuckler Feraud doing there, he wondered. He did not seem the sort of man who —

“Are you certain of what you say?” asked Lieut. D’Hubert.

The girl was perfectly certain. Without turning round to look at him, she explained that the coachman of their next door neighbours knew the maitre-d’hotel of Madame de Lionne. In this way she had her information. And she was perfectly certain. In giving this assurance she sighed. Lieut. Feraud called there nearly every afternoon, she added.

“Ah, bah!” exclaimed D’Hubert, ironically. His opinion of Madame de Lionne went down several degrees. Lieut. Feraud did not seem to him specially worthy of attention on the part of a woman with a reputation for sensibility and elegance. But there was no saying. At bottom they were all alike — very practical rather than idealistic. Lieut. D’Hubert, however, did not allow his mind to dwell on these considerations.

“By thunder!” he reflected aloud. “The general goes there sometimes. If he happens to find the fellow making eyes at the lady there will be the devil to pay! Our general is not a very accommodating person, I can tell you.”

“Go quickly, then! Don’t stand here now I’ve told you where he is!” cried the girl, colouring to the eyes.

“Thanks, my dear! I don’t know what I would have done without you.”

After manifesting his gratitude in an aggressive way, which at first was repulsed violently, and then submitted to with a sudden and still more repellent indifference, Lieut. D’Hubert took his departure.

He clanked and jingled along the streets with a martial swagger. To run a comrade to earth in a drawing-room where he was not known did not trouble him in the least. A uniform is a passport. His position as officier d’ordonnance of the general added to his assurance. Moreover, now that he knew where to find Lieut. Feraud, he had no option. It was a service matter.

Madame de Lionne’s house had an excellent appearance. A man in livery, opening the door of a large drawing-room with a waxed floor, shouted his name and stood aside to let him pass. It was a reception day. The ladies wore big hats surcharged with a profusion of feathers; their bodies sheathed in clinging white gowns, from the armpits to the tips of the low satin shoes, looked sylph-like and cool in a great display of bare necks and arms. The men who talked with them, on the contrary, were arrayed heavily in multi-coloured garments with collars up to their ears and thick sashes round their waists. Lieut. D’Hubert made his unabashed way across the room and, bowing low before a sylph-like form reclining on a couch, offered his apologies for this intrusion, which nothing could excuse but the extreme urgency of the service order he had to communicate to his comrade Feraud. He proposed to himself to return presently in a more regular manner and beg forgiveness for interrupting the interesting conversation. . .

A bare arm was extended towards him with gracious nonchalance even before he had finished speaking. He pressed the hand respectfully to his lips, and made the mental remark that it was bony. Madame de Lionne was a blonde, with too fine a skin and a long face.

“C’est ca!” she said, with an ethereal smile, disclosing a set of large teeth. “Come this evening to plead for your forgiveness.”

“I will not fail, madame.”

Meantime, Lieut. Feraud, splendid in his new dolman and the extremely polished boots of his calling, sat on a chair within a foot of the couch, one hand resting on his thigh, the other twirling his moustache to a point. At a significant glance from D’Hubert he rose without alacrity, and followed him into the recess of a window.

“What is it you want with me?” he asked, with astonishing indifference. Lieut. D’Hubert could not imagine that in the innocence of his heart and simplicity of his conscience Lieut. Feraud took a view of his duel in which neither remorse nor yet a rational apprehension of consequences had any place. Though he had no clear recollection how the quarrel had originated (it was begun in an establishment where beer and wine are drunk late at night), he had not the slightest doubt of being himself the outraged party. He had had two experienced friends for his seconds. Everything had been done according to the rules governing that sort of adventures. And a duel is obviously fought for the purpose of someone being at least hurt, if not killed outright. The civilian got hurt. That also was in order. Lieut. Feraud was perfectly tranquil; but Lieut. D’Hubert took it for affectation, and spoke with a certain vivacity.

“I am directed by the general to give you the order to go at once to your quarters, and remain there under close arrest.”

It was now the turn of Lieut. Feraud to be astonished. “What the devil are you telling me there?” he murmured, faintly, and fell into such profound wonder that he could only follow mechanically the motions of Lieut. D’Hubert. The two officers, one tall, with an interesting face and a moustache the colour of ripe corn, the other, short and sturdy, with a hooked nose and a thick crop of black curly hair, approached the mistress of the house to take their leave. Madame de Lionne, a woman of eclectic taste, smiled upon these armed young men with impartial sensibility and an equal share of interest. Madame de Lionne took her delight in the infinite variety of the human species. All the other eyes in the drawing-room followed the departing officers; and when they had gone out one or two men, who had already heard of the duel, imparted the information to the sylph-like ladies, who received it with faint shrieks of humane concern.

Meantime, the two hussars walked side by side, Lieut. Feraud trying to master the hidden reason of things which in this instance eluded the grasp of his intellect, Lieut. D’Hubert feeling annoyed at the part he had to play, because the general’s instructions were that he should see personally that Lieut. Feraud carried out his orders to the letter, and at once.

“The chief seems to know this animal,” he thought, eyeing his companion, whose round face, the round eyes, and even the twisted-up jet black little moustache seemed animated by a mental exasperation against the incomprehensible. And aloud he observed rather reproachfully, “The general is in a devilish fury with you!”

Lieut. Feraud stopped short on the edge of the pavement, and cried in accents of unmistakable sincerity, “What on earth for?” The innocence of the fiery Gascon soul was depicted in the manner in which he seized his head in both hands as if to prevent it bursting with perplexity.

“For the duel,” said Lieut. D’Hubert, curtly. He was annoyed greatly by this sort of perverse fooling.

“The duel! The. . .”

Lieut. Feraud passed from one paroxysm of astonishment into another. He dropped his hands and walked on slowly, trying to reconcile this information with the state of his own feelings. It was impossible. He burst out indignantly, “Was I to let that sauerkraut-eating civilian wipe his boots on the uniform of the 7th Hussars?”

Lieut. D’Hubert could not remain altogether unmoved by that simple sentiment. This little fellow was a lunatic, he thought to himself, but there was something in what he said.

“Of course, I don’t know how far you were justified,” he began, soothingly. “And the general himself may not be exactly informed. Those people have been deafening him with their lamentations.”

“Ah! the general is not exactly informed,” mumbled Lieut. Feraud, walking faster and faster as his choler at the injustice of his fate began to rise. “He is not exactly . . . And he orders me under close arrest, with God knows what afterwards!”

“Don’t excite yourself like this,” remonstrated the other. “Your adversary’s people are very influential, you know, and it looks bad enough on the face of it. The general had to take notice of their complaint at once. I don’t think he means to be over-severe with you. It’s the best thing for you to be kept out of sight for a while.”

“I am very much obliged to the general,” muttered Lieut. Feraud through his teeth. “And perhaps you would say I ought to be grateful to you, too, for the trouble you have taken to hunt me up in the drawing-room of a lady who —”

“Frankly,” interrupted Lieut. D’Hubert, with an innocent laugh, “I think you ought to be. I had no end of trouble to find out where you were. It wasn’t exactly the place for you to disport yourself in under the circumstances. If the general had caught you there making eyes at the goddess of the temple . . . oh, my word! . . . He hates to be bothered with complaints against his officers, you know. And it looked uncommonly like sheer bravado.”

The two officers had arrived now at the street door of Lieut. Feraud’s lodgings. The latter turned towards his companion. “Lieut. D’Hubert,” he said, “I have something to say to you, which can’t be said very well in the street. You can’t refuse to come up.”

The pretty maid had opened the door. Lieut. Feraud brushed past her brusquely, and she raised her scared and questioning eyes to Lieut. D’Hubert, who could do nothing but shrug his shoulders slightly as he followed with marked reluctance.

In his room Lieut. Feraud unhooked the clasp, flung his new dolman on the bed, and, folding his arms across his chest, turned to the other hussar.

“Do you imagine I am a man to submit tamely to injustice?” he inquired, in a boisterous voice.

“Oh, do be reasonable!” remonstrated Lieut. D’Hubert.

“I am reasonable! I am perfectly reasonable!” retorted the other with ominous restraint. “I can’t call the general to account for his behaviour, but you are going to answer me for yours.”

“I can’t listen to this nonsense,” murmured Lieut. D’Hubert, making a slightly contemptuous grimace.

“You call this nonsense? It seems to me a perfectly plain statement. Unless you don’t understand French.”

“What on earth do you mean?”

“I mean,” screamed suddenly Lieut. Feraud, “to cut off your ears to teach you to disturb me with the general’s orders when I am talking to a lady!”

A profound silence followed this mad declaration; and through the open window Lieut. D’Hubert heard the little birds singing sanely in the garden. He said, preserving his calm, “Why! If you take that tone, of course I shall hold myself at your disposition whenever you are at liberty to attend to this affair; but I don’t think you will cut my ears off.”

“I am going to attend to it at once,” declared Lieut. Feraud, with extreme truculence. “If you are thinking of displaying your airs and graces to-night in Madame de Lionne’s salon you are very much mistaken.”

“Really!” said Lieut. D’Hubert, who was beginning to feel irritated, “you are an impracticable sort of fellow. The general’s orders to me were to put you under arrest, not to carve you into small pieces. Goodmorning!” And turning his back on the little Gascon, who, always sober in his potations, was as though born intoxicated with the sunshine of his vine-ripening country, the Northman, who could drink hard on occasion, but was born sober under the watery skies of Picardy, made for the door. Hearing, however, the unmistakable sound behind his back of a sword drawn from the scabbard, he had no option but to stop.

“Devil take this mad Southerner!” he thought, spinning round and surveying with composure the warlike posture of Lieut. Feraud, with a bare sword in his hand.

“At once! — at once!” stuttered Feraud, beside himself.

“You had my answer,” said the other, keeping his temper very well.

At first he had been only vexed, and somewhat amused; but now his face got clouded. He was asking himself seriously how he could manage to get away. It was impossible to run from a man with a sword, and as to fighting him, it seemed completely out of the question. He waited awhile, then said exactly what was in his heart.

“Drop this! I won’t fight with you. I won’t be made ridiculous.”

“Ah, you won’t?” hissed the Gascon. “I suppose you prefer to be made infamous. Do you hear what I say? . . . Infamous! Infamous! Infamous!” he shrieked, rising and falling on his toes and getting very red in the face.

Lieut. D’Hubert, on the contrary, became very pale at the sound of the unsavoury word for a moment, then flushed pink to the roots of his fair hair. “But you can’t go out to fight; you are under arrest, you lunatic!” he objected, with angry scorn.

“There’s the garden: it’s big enough to lay out your long carcass in,” spluttered the other with such ardour that somehow the anger of the cooler man subsided.

“This is perfectly absurd,” he said, glad enough to think he had found a way out of it for the moment. “We shall never get any of our comrades to serve as seconds. It’s preposterous.”

“Seconds! Damn the seconds! We don’t want any seconds. Don’t you worry about any seconds. I shall send word to your friends to come and bury you when I am done. And if you want any witnesses, I’ll send word to the old girl to put her head out of a window at the back. Stay! There’s the gardener. He’ll do. He’s as deaf as a post, but he has two eyes in his head. Come along! I will teach you, my staff officer, that the carrying about of a general’s orders is not always child’s play.”

While thus discoursing he had unbuckled his empty scabbard. He sent it flying under the bed, and, lowering the point of the sword, brushed past the perplexed Lieut. D’Hubert, exclaiming, “Follow me!” Directly he had flung open the door a faint shriek was heard and the pretty maid, who had been listening at the keyhole, staggered away, putting the backs of her hands over her eyes. Feraud did not seem to see her, but she ran after him and seized his left arm. He shook her off, and then she rushed towards Lieut. D’Hubert and clawed at the sleeve of his uniform.

“Wretched man!” she sobbed. “Is this what you wanted to find him for?”

“Let me go,” entreated Lieut. D’Hubert, trying to disengage himself gently. “It’s like being in a madhouse,” he protested, with exasperation. “Do let me go! I won’t do him any harm.”

A fiendish laugh from Lieut. Feraud commented that assurance. “Come along!” he shouted, with a stamp of his foot.

And Lieut. D’Hubert did follow. He could do nothing else. Yet in vindication of his sanity it must be recorded that as he passed through the ante-room the notion of opening the street door and bolting out presented itself to this brave youth, only of course to be instantly dismissed, for he felt sure that the other would pursue him without shame or compunction. And the prospect of an officer of hussars being chased along the street by another officer of hussars with a naked sword could not be for a moment entertained. Therefore he followed into the garden. Behind them the girl tottered out, too. With ashy lips and wild, scared eyes, she surrendered herself to a dreadful curiosity. She had also the notion of rushing if need be between Lieut. Feraud and death.

The deaf gardener, utterly unconscious of approaching footsteps, went on watering his flowers till Lieut. Feraud thumped him on the back. Beholding suddenly an enraged man flourishing a big sabre, the old chap trembling in all his limbs dropped the watering-pot. At once Lieut. Feraud kicked it away with great animosity, and, seizing the gardener by the throat, backed him against a tree. He held him there, shouting in his ear, “Stay here, and look on! You understand? You’ve got to look on! Don’t dare budge from the spot!”

Lieut. D’Hubert came slowly down the walk, unclasping his dolman with unconcealed disgust. Even then, with his hand already on the hilt of his sword, he hesitated to draw till a roar, “En garde, fichtre! What do you think you came here for?” and the rush of his adversary forced him to put himself as quickly as possible in a posture of defence.

The clash of arms filled that prim garden, which hitherto had known no more warlike sound than the click of clipping shears; and presently the upper part of an old lady’s body was projected out of a window upstairs. She tossed her arms above her white cap, scolding in a cracked voice. The gardener remained glued to the tree, his toothless mouth open in idiotic astonishment, and a little farther up the path the pretty girl, as if spellbound to a small grass plot, ran a few steps this way and that, wringing her hands and muttering crazily. She did not rush between the combatants: the onslaughts of Lieut. Feraud were so fierce that her heart failed her. Lieut. D’Hubert, his faculties concentrated upon defence, needed all his skill and science of the sword to stop the rushes of his adversary. Twice already he had to break ground. It bothered him to feel his foothold made insecure by the round, dry gravel of the path rolling under the hard soles of his boots. This was most unsuitable ground, he thought, keeping a watchful, narrowed gaze, shaded by long eyelashes, upon the fiery stare of his thick-set adversary. This absurd affair would ruin his reputation of a sensible, well-behaved, promising young officer. It would damage, at any rate, his immediate prospects, and lose him the good-will of his general. These worldly preoccupations were no doubt misplaced in view of the solemnity of the moment. A duel, whether regarded as a ceremony in the cult of honour, or even when reduced in its moral essence to a form of manly sport, demands a perfect singleness of intention, a homicidal austerity of mood. On the other hand, this vivid concern for his future had not a bad effect inasmuch as it began to rouse the anger of Lieut. D’Hubert. Some seventy seconds had elapsed since they had crossed blades, and Lieut. D’Hubert had to break ground again in order to avoid impaling his reckless adversary like a beetle for a cabinet of specimens. The result was that misapprehending the motive, Lieut. Feraud with a triumphant sort of snarl pressed his attack.

“This enraged animal will have me against the wall directly,” thought Lieut. D’Hubert. He imagined himself much closer to the house than he was, and he dared not turn his head; it seemed to him that he was keeping his adversary off with his eyes rather more than with his point. Lieut. Feraud crouched and bounded with a fierce tigerish agility fit to trouble the stoutest heart. But what was more appalling than the fury of a wild beast, accomplishing in all innocence of heart a natural function, was the fixity of savage purpose man alone is capable of displaying. Lieut. D ‘Hubert in the midst of his worldly preoccupations perceived it at last. It was an absurd and damaging affair to be drawn into, but whatever silly intention the fellow had started with, it was clear enough that by this time he meant to kill — nothing less. He meant it with an intensity of will utterly beyond the inferior faculties of a tiger.

As is the case with constitutionally brave men, the full view of the danger interested Lieut. D’Hubert. And directly he got properly interested, the length of his arm and the coolness of his head told in his favour. It was the turn of Lieut. Feraud to recoil, with a blood-curdling grunt of baffled rage. He made a swift feint, and then rushed straight forward.

“Ah! you would, would you?” Lieut. D’Hubert exclaimed, mentally. The combat had lasted nearly two minutes, time enough for any man to get embittered, apart from the merits of the quarrel. And all at once it was over. Trying to close breast to breast under his adversary’s guard Lieut. Feraud received a slash on his shortened arm. He did not feel it in the least, but it checked his rush, and his feet slipping on the gravel he fell backwards with great violence. The shock jarred his boiling brain into the perfect quietude of insensibility. Simultaneously with his fall the pretty servant-girl shrieked; but the old maiden lady at the window ceased her scolding, and began to cross herself piously.

Beholding his adversary stretched out perfectly still, his face to the sky, Lieut. D’Hubert thought he had killed him outright. The impression of having slashed hard enough to cut his man clean in two abode with him for a while in an exaggerated memory of the right good-will he had put into the blow. He dropped on his knees hastily by the side of the prostrate body. Discovering that not even the arm was severed, a slight sense of disappointment mingled with the feeling of relief. The fellow deserved the worst. But truly he did not want the death of that sinner. The affair was ugly enough as it stood, and Lieut. D’Hubert addressed himself at once to the task of stopping the bleeding. In this task it was his fate to be ridiculously impeded by the pretty maid. Rending the air with screams of horror, she attacked him from behind and, twining her fingers in his hair, tugged back at his head. Why she should choose to hinder him at this precise moment he could not in the least understand. He did not try. It was all like a very wicked and harassing dream. Twice to save himself from being pulled over he had to rise and fling her off. He did this stoically, without a word, kneeling down again at once to go on with his work. But the third time, his work being done, he seized her and held her arms pinned to her body. Her cap was half off, her face was red, her eyes blazed with crazy boldness. He looked mildly into them while she called him a wretch, a traitor, and a murderer many times in succession. This did not annoy him so much as the conviction that she had managed to scratch his face abundantly. Ridicule would be added to the scandal of the story. He imagined the adorned tale making its way through the garrison of the town, through the whole army on the frontier, with every possible distortion of motive and sentiment and circumstance, spreading a doubt upon the sanity of his conduct and the distinction of his taste even to the very ears of his honourable family. It was all very well for that fellow Feraud, who had no connections, no family to speak of, and no quality but courage, which, anyhow, was a matter of course, and possessed by every single trooper in the whole mass of French cavalry. Still holding down the arms of the girl in a strong grip, Lieut. D’Hubert glanced over his shoulder. Lieut. Feraud had opened his eyes. He did not move. Like a man just waking from a deep sleep he stared without any expression at the evening sky.

Lieut. D’Hubert’s urgent shouts to the old gardener produced no effect — not so much as to make him shut his toothless mouth. Then he remembered that the man was stone deaf. All that time the girl struggled, not with maidenly coyness, but like a pretty, dumb fury, kicking his shins now and then. He continued to hold her as if in a vice, his instinct telling him that were he to let her go she would fly at his eyes. But he was greatly humiliated by his position. At last she gave up. She was more exhausted than appeased, he feared. Nevertheless, he attempted to get out of this wicked dream by way of negotiation.

“Listen to me,” he said, as calmly as he could. “Will you promise to run for a surgeon if I let you go?”

With real affliction he heard her declare that she would do nothing of the kind. On the contrary, her sobbed out intention was to remain in the garden, and fight tooth and nail for the protection of the vanquished man. This was shocking.

“My dear child!” he cried in despair, “is it possible that you think me capable of murdering a wounded adversary? Is it. . . . Be quiet, you little wild cat, you!”

They struggled. A thick, drowsy voice said behind him, “What are you after with that girl?”

Lieut. Feraud had raised himself on his good arm. He was looking sleepily at his other arm, at the mess of blood on his uniform, at a small red pool on the ground, at his sabre lying a foot away on the path. Then he laid himself down gently again to think it all out, as far as a thundering headache would permit of mental operations.

Lieut. D’Hubert released the girl who crouched at once by the side of the other lieutenant. The shades of night were falling on the little trim garden with this touching group, whence proceeded low murmurs of sorrow and compassion, with other feeble sounds of a different character, as if an imperfectly awake invalid were trying to swear. Lieut. D’Hubert went away.

He passed through the silent house, and congratulated himself upon the dusk concealing his gory hands and scratched face from the passers-by. But this story could by no means be concealed. He dreaded the discredit and ridicule above everything, and was painfully aware of sneaking through the back streets in the manner of a murderer. Presently the sounds of a flute coming out of the open window of a lighted upstairs room in a modest house interrupted his dismal reflections. It was being played with a persevering virtuosity, and through the fioritures of the tune one could hear the regular thumping of the foot beating time on the floor.

Lieut. D’Hubert shouted a name, which was that of an army surgeon whom he knew fairly well. The sounds of the flute ceased, and the musician appeared at the window, his instrument still in his hand, peering into the street.

“Who calls? You, D’Hubert? What brings you this way?”

He did not like to be disturbed at the hour when he was playing the flute. He was a man whose hair had turned grey already in the thankless task of tying up wounds on battlefields where others reaped advancement and glory.

“I want you to go at once and see Feraud. You know Lieut. Feraud? He lives down the second street. It’s but a step from here.”

“What’s the matter with him?”

“Wounded.”

“Are you sure?”

“Sure!” cried D’Hubert. “I come from there.”

“That’s amusing,” said the elderly surgeon. Amusing was his favourite word; but the expression of his face when he pronounced it never corresponded. He was a stolid man. “Come in,” he added. “I’ll get ready in a moment.”

“Thanks! I will. I want to wash my hands in your room.”

Lieut. D’Hubert found the surgeon occupied in unscrewing his flute, and packing the pieces methodically in a case. He turned his head.

“Water there — in the corner. Your hands do want washing.”

“I’ve stopped the bleeding,” said Lieut. D’Hubert. “But you had better make haste. It’s rather more than ten minutes ago, you know.”

The surgeon did not hurry his movements.

“What’s the matter? Dressing came off? That’s amusing. I’ve been at work in the hospital all day but I’ve been told this morning by somebody that he had come off without a scratch.”

“Not the same duel probably,” growled moodily Lieut. D’Hubert, wiping his hands on a coarse towel.

“Not the same. . . . What? Another. It would take the very devil to make me go out twice in one day.” The surgeon looked narrowly at Lieut. D’Hubert. “How did you come by that scratched face? Both sides, too — and symmetrical. It’s amusing.”

“Very!” snarled Lieut. D’Hubert. “And you will find his slashed arm amusing, too. It will keep both of you amused for quite a long time.”

The doctor was mystified and impressed by the brusque bitterness of Lieut. D’Hubert’s tone. They left the house together, and in the street he was still more mystified by his conduct.

“Aren’t you coming with me?” he asked.

“No,” said Lieut. D’Hubert. “You can find the house by yourself. The front door will be standing open very likely.”

“All right. Where’s his room?”

“Ground floor. But you had better go right through and look in the garden first.”

This astonishing piece of information made the surgeon go off without further parley. Lieut. D’Hubert regained his quarters nursing a hot and uneasy indignation. He dreaded the chaff of his comrades almost as much as the anger of his superiors. The truth was confoundedly grotesque and embarrassing, even putting aside the irregularity of the combat itself, which made it come abominably near a criminal offence. Like all men without much imagination, a faculty which helps the process of reflective thought, Lieut. D’Hubert became frightfully harassed by the obvious aspects of his predicament. He was certainly glad that he had not killed Lieut. Feraud outside all rules, and without the regular witnesses proper to such a transaction. Uncommonly glad. At the same time he felt as though he would have liked to wring his neck for him without ceremony.

He was still under the sway of these contradictory sentiments when the surgeon amateur of the flute came to see him. More than three days had elapsed. Lieut. D’Hubert was no longer officier d’ordonnance to the general commanding the division. He had been sent back to his regiment. And he was resuming his connection with the soldiers’ military family by being shut up in close confinement, not at his own quarters in town, but in a room in the barracks. Owing to the gravity of the incident, he was forbidden to see any one. He did not know what had happened, what was being said, or what was being thought. The arrival of the surgeon was a most unexpected thing to the worried captive. The amateur of the flute began by explaining that he was there only by a special favour of the colonel.

“I represented to him that it would be only fair to let you have some authentic news of your adversary,” he continued. “You’ll be glad to hear he’s getting better fast.”

Lieut. D’Hubert’s face exhibited no conventional signs of gladness. He continued to walk the floor of the dusty bare room.

“Take this chair, doctor,” he mumbled.

The doctor sat down.

“This affair is variously appreciated — in town and in the army. In fact, the diversity of opinions is amusing.”

“Is it!” mumbled Lieut. D’Hubert, tramping steadily from wall to wall. But within himself he marvelled that there could be two opinions on the matter. The surgeon continued.

“Of course, as the real facts are not known —”

“I should have thought,” interrupted D’Hubert, “that the fellow would have put you in possession of facts.”

“He said something,” admitted the other, “the first time I saw him. And, by the by, I did find him in the garden. The thump on the back of his head had made him a little incoherent then. Afterwards he was rather reticent than otherwise.”

“Didn’t think he would have the grace to be ashamed!” mumbled D’Hubert, resuming his pacing while the doctor murmured, “It’s very amusing. Ashamed! Shame was not exactly his frame of mind. However, you may look at the matter otherwise.”

“What are you talking about? What matter?” asked D’Hubert, with a sidelong look at the heavy-faced, grey-haired figure seated on a wooden chair.

“Whatever it is,” said the surgeon a little impatiently, “I don’t want to pronounce any opinion on your conduct —”

“By heavens, you had better not!” burst out D’Hubert.

“There! — there! Don’t be so quick in flourishing the sword. It doesn’t pay in the long run. Understand once for all that I would not carve any of you youngsters except with the tools of my trade. But my advice is good. If you go on like this you will make for yourself an ugly reputation.”

“Go on like what?” demanded Lieut. D’Hubert, stopping short, quite startled. “I! — I! — make for myself a reputation. . . . What do you imagine?”

“I told you I don’t wish to judge of the rights and wrongs of this incident. It’s not my business. Nevertheless —”

“What on earth has he been telling you?” interrupted Lieut. D’Hubert, in a sort of awed scare.

“I told you already, that at first, when I picked him up in the garden, he was incoherent. Afterwards he was naturally reticent. But I gather at least that he could not help himself.”

“He couldn’t?” shouted Lieut. D’Hubert in a great voice. Then, lowering his tone impressively, “And what about me? Could I help myself?”

The surgeon stood up. His thoughts were running upon the flute, his constant companion with a consoling voice. In the vicinity of field ambulances, after twenty-four hours’ hard work, he had been known to trouble with its sweet sounds the horrible stillness of battlefields, given over to silence and the dead. The solacing hour of his daily life was approaching, and in peace time he held on to the minutes as a miser to his hoard.

“Of course! — of course!” he said, perfunctorily. “You would think so. It’s amusing. However, being perfectly neutral and friendly to you both, I have consented to deliver his message to you. Say that I am humouring an invalid if you like. He wants you to know that this affair is by no means at an end. He intends to send you his seconds directly he has regained his strength — providing, of course, the army is not in the field at that time.”

“He intends, does he? Why, certainly,” spluttered Lieut. D’Hubert in a passion.

The secret of his exasperation was not apparent to the visitor; but this passion confirmed the surgeon in the belief which was gaining ground outside that some very serious difference had arisen between these two young men, something serious enough to wear an air of mystery, some fact of the utmost gravity. To settle their urgent difference about that fact, those two young men had risked being broken and disgraced at the outset almost of their career. The surgeon feared that the forthcoming inquiry would fail to satisfy the public curiosity. They would not take the public into their confidence as to that something which had passed between them of a nature so outrageous as to make them face a charge of murder — neither more nor less. But what could it be?

The surgeon was not very curious by temperament; but that question haunting his mind caused him twice that evening to hold the instrument off his lips and sit silent for a whole minute — right in the middle of a tune — trying to form a plausible conjecture.

II

––––––––

HE SUCCEEDED IN THIS object no better than the rest of the garrison and the whole of society. The two young officers, of no especial consequence till then, became distinguished by the universal curiosity as to the origin of their quarrel. Madame de Lionne’s salon was the centre of ingenious surmises; that lady herself was for a time assailed by inquiries as being the last person known to have spoken to these unhappy and reckless young men before they went out together from her house to a savage encounter with swords, at dusk, in a private garden. She protested she had not observed anything unusual in their demeanour. Lieut. Feraud had been visibly annoyed at being called away. That was natural enough; no man likes to be disturbed in a conversation with a lady famed for her elegance and sensibility. But in truth the subject bored Madame de Lionne, since her personality could by no stretch of reckless gossip be connected with this affair. And it irritated her to hear it advanced that there might have been some woman in the case. This irritation arose, not from her elegance or sensibility, but from a more instinctive side of her nature. It became so great at last that she peremptorily forbade the subject to be mentioned under her roof. Near her couch the prohibition was obeyed, but farther off in the salon the pall of the imposed silence continued to be lifted more or less. A personage with a long, pale face, resembling the countenance of a sheep, opined, shaking his head, that it was a quarrel of long standing envenomed by time. It was objected to him that the men themselves were too young for such a theory. They belonged also to different and distant parts of France. There were other physical impossibilities, too. A sub-commissary of the Intendence, an agreeable and cultivated bachelor in kerseymere breeches, Hessian boots, and a blue coat embroidered with silver lace, who affected to believe in the transmigration of souls, suggested that the two had met perhaps in some previous existence. The feud was in the forgotten past. It might have been something quite inconceivable in the present state of their being; but their souls remembered the animosity, and manifested an instinctive antagonism. He developed this theme jocularly. Yet the affair was so absurd from the worldly, the military, the honourable, or the prudential point of view, that this weird explanation seemed rather more reasonable than any other.

The two officers had confided nothing definite to any one. Humiliation at having been worsted arms in hand, and an uneasy feeling of having been involved in a scrape by the injustice of fate, kept Lieut. Feraud savagely dumb. He mistrusted the sympathy of mankind. That would, of course, go to that dandified staff officer. Lying in bed, he raved aloud to the pretty maid who administered to his needs with devotion, and listened to his horrible imprecations with alarm. That Lieut. D’Hubert should be made to “pay for it,” seemed to her just and natural. Her principal care was that Lieut. Feraud should not excite himself. He appeared so wholly admirable and fascinating to the humility of her heart that her only concern was to see him get well quickly, even if it were only to resume his visits to Madame de Lionne’s salon.

Lieut. D’Hubert kept silent for the immediate reason that there was no one, except a stupid young soldier servant, to speak to. Further, he was aware that the episode, so grave professionally, had its comic side. When reflecting upon it, he still felt that he would like to wring Lieut. Feraud’s neck for him. But this formula was figurative rather than precise, and expressed more a state of mind than an actual physical impulse. At the same time, there was in that young man a feeling of comradeship and kindness which made him unwilling to make the position of Lieut. Feraud worse than it was. He did not want to talk at large about this wretched affair. At the inquiry he would have, of course, to speak the truth in self-defence. This prospect vexed him.

But no inquiry took place. The army took the field instead. Lieut. D’Hubert, liberated without remark, took up his regimental duties; and Lieut. Feraud, his arm just out of the sling, rode unquestioned with his squadron to complete his convalescence in the smoke of battlefields and the fresh air of night bivouacs. This bracing treatment suited him so well, that at the first rumour of an armistice being signed he could turn without misgivings to the thoughts of his private warfare.

This time it was to be regular warfare. He sent two friends to Lieut. D’Hubert, whose regiment was stationed only a few miles away. Those friends had asked no questions of their principal. “I owe him one, that pretty staff officer,” he had said, grimly, and they went away quite contentedly on their mission. Lieut. D’Hubert had no difficulty in finding two friends equally discreet and devoted to their principal. “There’s a crazy fellow to whom I must give a lesson,” he had declared curtly; and they asked for no better reasons.

On these grounds an encounter with duelling-swords was arranged one early morning in a convenient field. At the third set-to Lieut. D’Hubert found himself lying on his back on the dewy grass with a hole in his side. A serene sun rising over a landscape of meadows and woods hung on his left. A surgeon — not the flute player, but another — was bending over him, feeling around the wound.

“Narrow squeak. But it will be nothing,” he pronounced.

Lieut. D’Hubert heard these words with pleasure. One of his seconds, sitting on the wet grass, and sustaining his head on his lap, said, “The fortune of war, mon pauvre vieux. What will you have? You had better make it up like two good fellows. Do!”

“You don’t know what you ask,” murmured Lieut. D’Hubert, in a feeble voice. “However, if he. . .”

In another part of the meadow the seconds of Lieut. Feraud were urging him to go over and shake hands with his adversary.

“You have paid him off now — que diable. It’s the proper thing to do. This D’Hubert is a decent fellow.”

“I know the decency of these generals’ pets,” muttered Lieut. Feraud through his teeth, and the sombre expression of his face discouraged further efforts at reconciliation. The seconds, bowing from a distance, took their men off the field. In the afternoon Lieut. D’Hubert, very popular as a good comrade uniting great bravery with a frank and equable temper, had many visitors. It was remarked that Lieut. Feraud did not, as is customary, show himself much abroad to receive the felicitations of his friends. They would not have failed him, because he, too, was liked for the exuberance of his southern nature and the simplicity of his character. In all the places where officers were in the habit of assembling at the end of the day the duel of the morning was talked over from every point of view. Though Lieut. D’Hubert had got worsted this time, his sword play was commended. No one could deny that it was very close, very scientific. It was even whispered that if he got touched it was because he wished to spare his adversary. But by many the vigour and dash of Lieut. Feraud’s attack were pronounced irresistible.

The merits of the two officers as combatants were frankly discussed; but their attitude to each other after the duel was criticised lightly and with caution. It was irreconcilable, and that was to be regretted. But after all they knew best what the care of their honour dictated. It was not a matter for their comrades to pry into over-much. As to the origin of the quarrel, the general impression was that it dated from the time they were holding garrison in Strasbourg. The musical surgeon shook his head at that. It went much farther back, he thought.

“Why, of course! You must know the whole story,” cried several voices, eager with curiosity. “What was it?”

He raised his eyes from his glass deliberately. “Even if I knew ever so well, you can’t expect me to tell you, since both the principals choose to say nothing.”

He got up and went out, leaving the sense of mystery behind him. He could not stay any longer, because the witching hour of flute-playing was drawing near.

After he had gone a very young officer observed solemnly, “Obviously, his lips are sealed!”

Nobody questioned the high correctness of that remark. Somehow it added to the impressiveness of the affair. Several older officers of both regiments, prompted by nothing but sheer kindness and love of harmony, proposed to form a Court of Honour, to which the two young men would leave the task of their reconciliation. Unfortunately they began by approaching Lieut. Feraud, on the assumption that, having just scored heavily, he would be found placable and disposed to moderation.

The reasoning was sound enough. Nevertheless, the move turned out unfortunate. In that relaxation of moral fibre, which is brought about by the ease of soothed vanity, Lieut. Feraud had condescended in the secret of his heart to review the case, and even had come to doubt not the justice of his cause, but the absolute sagacity of his conduct. This being so, he was disinclined to talk about it. The suggestion of the regimental wise men put him in a difficult position. He was disgusted at it, and this disgust, by a paradoxical logic, reawakened his animosity against Lieut. D’Hubert. Was he to be pestered with this fellow for ever — the fellow who had an infernal knack of getting round people somehow? And yet it was difficult to refuse point blank that mediation sanctioned by the code of honour.

He met the difficulty by an attitude of grim reserve. He twisted his moustache and used vague words. His case was perfectly clear. He was not ashamed to state it before a proper Court of Honour, neither was he afraid to defend it on the ground. He did not see any reason to jump at the suggestion before ascertaining how his adversary was likely to take it.

Later in the day, his exasperation growing upon him, he was heard in a public place saying sardonically, “that it would be the very luckiest thing for Lieut. D’Hubert, because the next time of meeting he need not hope to get off with the mere trifle of three weeks in bed.”

This boastful phrase might have been prompted by the most profound Machiavellism. Southern natures often hide, under the outward impulsiveness of action and speech, a certain amount of astuteness.

Lieut. Feraud, mistrusting the justice of men, by no means desired a Court of Honour; and the above words, according so well with his temperament, had also the merit of serving his turn. Whether meant so or not, they found their way in less than four-and-twenty hours into Lieut. D’Hubert’s bedroom. In consequence Lieut. D’Hubert, sitting propped up with pillows, received the overtures made to him next day by the statement that the affair was of a nature which could not bear discussion.

The pale face of the wounded officer, his weak voice which he had yet to use cautiously, and the courteous dignity of his tone had a great effect on his hearers. Reported outside all this did more for deepening the mystery than the vapourings of Lieut. Feraud. This last was greatly relieved at the issue. He began to enjoy the state of general wonder, and was pleased to add to it by assuming an attitude of fierce discretion.