Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

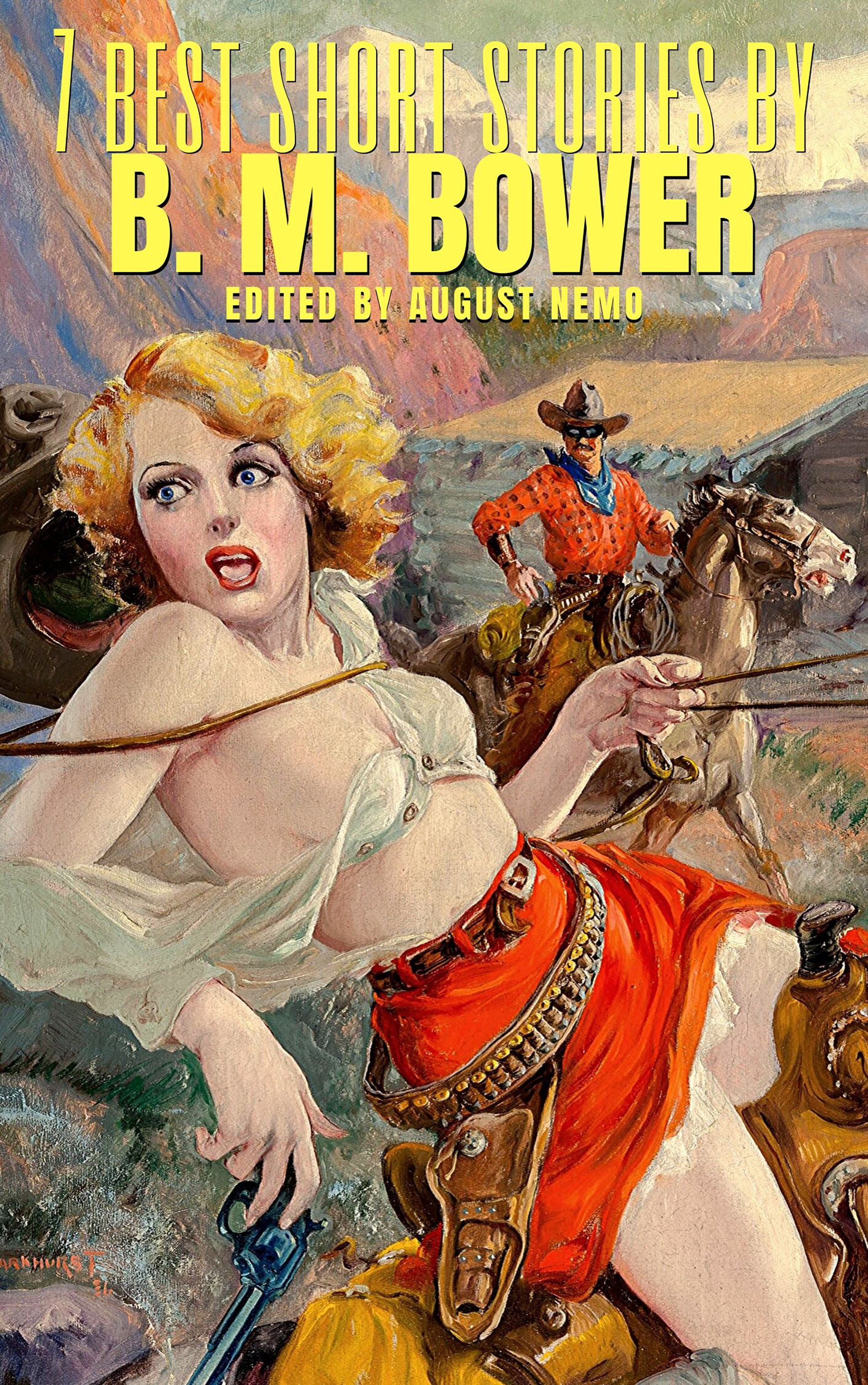

- Herausgeber: Tacet Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: 7 best short stories

- Sprache: Englisch

B. M. Bower, was an American author who wrote novels, fictional short stories, and screenplays about the American Old West. Her works, featuring cowboys and cows of the Flying U Ranch in Montana, reflected "an interest in ranch life, the use of working cowboys as main characters, the occasional appearance of eastern types for the sake of contrast, a sense of western geography as simultaneously harsh and grand, and a good deal of factual attention to such matters as cattle branding and bronc busting." For this book, the critic August Nemo selected seven short stories by this author: - The Lonesome Trail. - First Aid To Cupid. - When The Cook Fell Ill. - The Lamb. - The Spirit of the Range. - The Reveler. - The Unheavenly Twins

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 260

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title Page

The Author

THE LONESOME TRAIL

FIRST AID TO CUPID

WHEN THE COOK FELL ILL

THE LAMB

THE SPIRIT OF THE RANGE

THE REVELER

THE UNHEAVENLY TWINS

About the Publisher

The Author

B.M. Bower, in full Bertha Muzzy Sinclair Bower, (born November 15, 1871, Cleveland, Minnesota, U.S.—died July 23, 1940, Los Angeles, California), American author and screenwriter known for her stories set in the American West.

She was born Bertha Muzzy. She moved as a small child with her family from Minnesota to Montana, where she gained the firsthand experience of ranch life that was central to her novels and screenplays. She married Clayton J. Bower at age 18 and became a schoolteacher as well as the mother of three children. She divorced him in 1905 and married Bertrand W. Sinclair the following year. The union lasted six years. She married her third husband, Robert Ellsworth Cowan, in 1920.

Her first published work appeared in the pulp publication The Popular Magazine in 1904, and in 1906 she published her first novel, Chip, of the Flying U, about the lives of cowboy Chip Bennett and his group of hands at the Flying U ranch. She revisited the characters in several sequels, including The Happy Family (1910) and Flying U Ranch (1914). These novels achieved significant popularity in the United States, becoming standards for many Americans who knew little of life in the West.

Bower wrote more than 60 books in her 40-year career. Her first collection of short stories, The Lonesome Trail, appeared in 1909. Other novels include Lonesome Land (1912), The Heritage of the Sioux (1916), Cabin Fever (1918), and The Five Furies of Leaning Ladder (1936). Bower converted several of her novels into screenplays, and her involvement with Hollywood led to a fascination with the film industry that found its way into her later novels. More than 10 films based on her works were produced.

Bower’s writing, intended for a commercial audience eager to learn about the adventures of cowboys and ranchers, was not always praised by critics, who viewed the western genre as sensationalist or melodramatic. Her work was unusual for its time, however, in featuring female characters that were as developed as their male counterparts.

THE LONESOME TRAIL

PART ONE

A man is very much like a horse. Once thoroughly frightened by something he meets on the road, he will invariably shy at the same place afterwards, until a wisely firm master leads him perforce to the spot and proves beyond all doubt that the danger is of his own imagining; after which he will throw up his head and deny that he ever was afraid—and be quite amusingly sincere in the denial.

It is true of every man with high-keyed nature, a decent opinion of himself and a healthy pride of power. It was true of Will Davidson, of the Flying U—commonly known among his associates, particularly the Happy Family, as “Weary.” As to the cause of his shying at a certain object, that happened long ago. Many miles east of the Bear Paws, in the town where Weary had minced painfully along the streets on pink, protesting, bare soles before the frost was half out of the ground; had yelled himself hoarse and run himself lame in the redoubtable base-ball nine which was to make that town some day famous—the nine where they often played with seven “men” because the other two had to “bug” potatoes or do some other menial task and where the umpire frequently engaged in throwing lumps of dried mud at refractory players,—there had lived a Girl.

She might have lived there a century and Weary been none the worse, had he not acquired the unfortunate habit of growing up. Even then he might have escaped injury had he not persisted in growing up and up, a straight six-feet-two of lovable good looks, with the sunniest of tempers and blue eyes that reflected the warm sweetness of that nature, and a smile to tell what the eyes left unsaid.

Such being the tempting length of him, the Girl saw that he was worth an effort; she took to smoking the chimney of her bedroom lamp, heating curling irons, wearing her best hat and best ribbons on a weekday, and insisting upon crowding number four-and-a-half feet into number three-and-a-half shoes and managing to look as if she were perfectly comfortable. When a girl does all those things, and when she has a good complexion and hair vividly red and long, heavy-lidded blue eyes that have a fashion of looking side-long at a man, it were well for that man to travel—if he would keep the lightness of his heart and the sunny look in his eyes and his smile.

Weary traveled, but the trouble was that he did not go soon enough. When he did go, his eyes were somber instead of sunny, and he smiled not at all. And in his heart he carried a deep-rooted impulse to shy always at women—and so came to resemble a horse.

He shied at long, blue eyes and turned his own uncompromisingly away. He never would dance with a woman who had red hair, except in quadrilles where he could not help himself; and then his hand-clasp was brief and perfunctory when it came to “Grand right-and-left.” If commanded to “Balance-swing” the red-haired woman was swung airily by the finger-tips—; which was not the way in which Weary swung the others.

And then came the schoolma’am. The schoolma’am’s hair was the darkest brown and had a shine to it where the light struck at the proper angle, and her eyes were large and came near being round, and they were a velvety brown and also had a shine in them.

Still Weary shied consistently and systematically.

At the leap-year ball, given on New Year’s night, when the ladies were invited to “choose your pardners for the hull dance, regardless of who brought yuh,” the schoolma’am had forsaken Joe Meeker, with whose parents she boarded, and had deliberately chosen Weary. The Happy Family had, with one accord, grinned at him in a way that promised many things and, up to the coming of the Fourth of July, every promise had been conscientiously fulfilled.

They brought him many friendly messages from the schoolma’am, to which he returned unfriendly answers. When he accused them openly of trying to “load” him; they were shocked and grieved. They told him the schoolma’am said she felt drawn to him—he looked so like her darling brother who had spilled his precious blood on San Juan Hill. Cal Emmett was exceedingly proud of this invention, since it seemed to “go down” with Weary better than most of the lies they told.

It was the coming of the Fourth and the celebration of that day which provoked further effort to tease Weary.

“Who are you going to take, Weary?” Cal Emmett lowered his left eyelid very gently, for the benefit of the others, and drew a match sharply along the wall just over his head.

“Myself,” answered Weary sweetly, though it was becoming a sore subject.

“You’re sure going in bum company, then,” retorted Cal.

“Who’s going to pilot the schoolma’am?” blurted Happy Jack, who was never consciously ambiguous.

“You can search me,” said Weary, in a you-make-me-tired tone. “She sure isn’t going with Yours Truly.”

“Ain’t she asked yuh yet?” fleered Cal. “That’s funny. She told me the other day she was going to take advantage of woman’s privilege, this year, and choose her own escort for the dance. Then she asked me if I knew whether you were spoke for, and when I told her yuh wasn’t, she wanted to know if I’d bring a note over. But I was in a dickens of a hurry, and couldn’t wait for it; anyhow, I was headed the other way.”

“Not toward Len Adams, were you?” asked Weary sympathetically.

“Aw, she’ll give you an invite, all right,” Happy Jack declared. “Little Willie ain’t going to be forgot, yuh can gamble on that. He’s too much like Darling Brother—”

At this point, Happy Jack ducked precipitately and a flapping, four-buckled overshoe, a relic of the winter gone, hurtled past his head and landed with considerable force upon the unsuspecting stomach of Cal, stretched luxuriously upon his bunk. Cal doubled like a threatened caterpillar and groaned, and Weary, feeling that justice had not been defeated even though he had aimed at another culprit, grinned complacently.

“What horse are you going to take?” asked Chip, to turn the subject.

“Glory. I’m thinking of putting him up against Bert Rogers’ Flopper. Bert’s getting altogether too nifty over that cayuse of his. He needs to be walked away from, once; Glory’s the little horse that can learn ’em things about running, if—”

“Yeah—if!” This from Cal, who had recovered speech. “Have yuh got a written guarantee from Glory, that he’ll run?”

“Aw,” croaked Happy Jack, “if he runs at all, it’ll likely be backwards—if it ain’t a dancing-bear stunt on his hind feet. You can gamble it’ll be what yuh don’t expect and ain’t got any money on; that there’s Glory, from the ground up.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” Weary drawled placidly. “I’m not setting him before the public as a twin to Mary’s little lamb, but I’m willing to risk him. He’s a good little horse—when he feels that way—and he can run. And darn him, he’s got to run!”

Shorty quit snoring and rolled over. “Betche ten dollars, two to one, he won’t run,” he said, digging his fists into his eyes like a baby.

Weary, dead game, took him up, though he knew what desperate chances he was taking.

“Betche five dollars, even up, he runs backwards,” grinned Happy Jack, and Weary accepted that wager also.

The rest of the afternoon was filled with Glory—so to speak—and much coin was hazarded upon his doing every unseemly thing that a horse can possibly do at a race, except the one thing which he did do; which goes to prove that Glory was not an ordinary cayuse, and that he had a reputation to maintain. To the day of his death, it may be said, he maintained it.

Dry Lake was nothing if not patriotic. Every legal holiday was observed in true Dry Lake manner, to the tune of violins and the swish-swish of slippered feet upon a more-or-less polished floor. The Glorious Fourth, however, was celebrated with more elaborate amusements. On that day men met, organized and played a matched game of ball with much shouting and great gusto, and with an umpire who aimed to please.

After that they arranged their horseraces over the bar of the saloon, and rode, ran or walked to the quarter-mile stretch of level trail beyond the stockyards to witness the running; when they would hurry back to settle their bets over the bar where they had drunk to the preliminaries.

Bert Rogers came early, riding Flopper. Men hurried from the saloon to gather round the horse that held the record of beating a “real race-horse” the summer before. They felt his legs sagely and wondered that anyone should seem anxious to question his ability to beat anything in the country in a straightaway quarter-mile dash.

When the Flying U boys clattered into town in a bunch, they were greeted enthusiastically; for old Jim Whitmore’s “Happy Family” was liked to a man. The enthusiasm did not extend to Glory, however. He was eyed askance by those who knew him or who had heard of his exploits. If the Happy Family had not backed him loyally to a man, he would not have had a dollar risked upon him; and this not because he could not run.

Glory was an alien, one of a carload of horses shipped in from Arizona the summer before. He was a bright sorrel, with the silvery mane and tan and white feet which one so seldom sees—a beauty, none could deny. His temper was not so beautiful.

Sometimes for days he was lamblike in his obedience, touching in his muzzling affection till Weary was lulled into unwatchful love for the horse. Then things would happen.

Once, Weary walked with a cane for two weeks. Another time he walked ten miles in the rain. Once he did not walk at all, but sat on a rock and smoked cigarettes till his tobacco sack ran empty, waiting for Glory to quit sulking, flat on his side, and get up and carry him home.

Any man but Weary would have ruined the horse with harshness, but Weary was really proud of his deviltry and would laugh till the tears came while he told of some new and undreamed bit of cussedness in his pet.

On this day, Glory was behaving beautifully. True, he had nearly squeezed the life out of Weary that morning when he went to saddle him in the stall, and he had afterwards snatched Cal Emmet’s hat off with his teeth, and had dropped it to the ground and had stood upon it; but on the whole, the Happy Family regarded those trifles as a good sign.

When Bert Rogers and Weary ambled away down the dusty trail to the starting point, accompanied by most of the Flying U boys and two or three from Bert’s outfit, the crowd in the grand-stand (which was the top rail of the stockyard fence) hushed expectantly.

When a pistol cracked, far down the road, and a faint yell came shrilling through the quiet sunshine, they craned necks till their muscles ached. Like a summer sand-storm they came, and behind them clattered their friends, the dust concealing horse and rider alike. Whooping encouraging words at random, they waited till a black nose shot out from the rushing cloud. That was Flopper. Beside it a white streak, a flying, silvery mane—Glory was running! Happy Jack gave a raucous yell.

Lifting reluctantly, the dust gave hazy glimpses of a long, black body hugging jealously close to earth, its rider lying low upon the straining neck—that was Flopper and Bert.

Close beside, a sheeny glimmer of red, a tossing fringe of white, a leaning, wiry, exultant form above—that was Glory and Weary.

There were groans as well as shouting when the whirlwind had swept past and on down the hill toward town, and the reason thereof was plain. Glory had won by a good length of him.

Bert Rogers said something savage and set his weight upon the bit till Flopper, snorting and disgusted—for a horse knows when he is beaten—took shorter leaps, stiffened his front legs and stopped, digging furrows with his feet.

Glory sailed on down the trail, scattering Mrs. Jenson’s chickens and jumping clean over a lumbering, protesting sow. “Come on—he’s going to set up the drinks!” yelled someone, and the crowd leaped from the fence and followed.

But Glory did not stop. He whipped around the saloon, whirled past the blacksmith shop and was headed for the mouth of the lane before anyone understood. Then Chip, suddenly grasping the situation, dug deep with his spurs and yelled.

“He’s broken the bit—it’s a runaway!”

Thus began the second race, a free-for-all dash up the lane. At the very start they knew it was hopeless to attempt overtaking that red streak, but they galloped a mile for good manners’ sake; Cal then pulled up.

“No use,” he said. “Glory’s headed for home and we ain’t got the papers to stop him. He can’t hurt Weary—and the dance opens up at six, and I’ve got a girl in town.”

“Same here,” grinned Bert. “It’s after four, now.”

Chip, who at that time hadn’t a girl—and didn’t want one—let Silver out for another long gallop, seeing it was Weary. Then he, too, gave up the chase and turned back.

Glory settled to a long lope and kept steadily on, gleefully rattling the broken bit which dangled beneath his jaws. Weary, helpless and amused and triumphant because the race was his, sat unconcernedly in the saddle and laid imaginary bets with himself on the outcome. Without doubt, Glory was headed for home. Weary figured that, barring accidents, he could catch up Blazes, in the little pasture, and ride back to Dry Lake by the time the dance was in full swing—for the dancing before dark would be desultory and without much spirit.

But the gate into the big field was closed and tied securely with a rope. Glory comprehended the fact with one roll of his knowing eyes, turned away to the left and took the trail which wound like a snake into the foothills. Clinging warily to the level where choice was given him, trotting where the way was rough, mile after mile he covered till even Weary’s patience showed signs of weakening.

Just then Glory turned, where a wire gate lay flat upon the ground, crossed a pebbly creek and galloped stiffly up to the very steps of a squat, vine-covered ranch-house where, like the Discontented Pendulum in the fable, he suddenly stopped.

“Damn you, Glory—I could kill yuh for this!” gritted Weary, and slid reluctantly from the saddle. For while the place seemed deserted, it was not. There was a girl.

She lay in a hammock; sprawled would come nearer describing her position. She had some magazines scattered around upon the porch, and her hair hung down to the floor in a thick, dark braid. She was dressed in a dark skirt and what, to Weary’s untrained, masculine eyes, looked like a pink gunny sack. In reality it was a kimono. She appeared to be asleep.

Weary saw a chance of leading Glory quietly to the corral before she woke. There he could borrow a bridle and ride back whence he came, and he could explain about the bridle to Joe Meeker in town. Joe was always good about lending things, anyway. He gathered the fragments of the bit in one hand and clucked under his breath, in an agony lest his spurs should jingle.

Glory turned upon him his beautiful, brown eyes, reproachfully questioning.

Weary pulled steadily. Glory stretched neck and nose obediently, but as to feet, they were down to stay.

Weary glanced anxiously toward the hammock and perspired, then stood back and whispered language it would be a sin to repeat. Glory, listening with unruffled calm, stood perfectly still, like a red statue in the sunshine.

The face of the girl was hidden under one round, loose-sleeved arm. She did not move. A faint breeze, freshening in spasmodic puffs, seized upon the hammock, and set it swaying gently.

“Oh, damn you, Glory!” whispered Weary through his teeth. But Glory, accustomed to being damned since he was a yearling, displayed absolutely no interest. Indeed, he seemed inclined to doze there in the sun.

Taking his hat—his best hat—from his head, he belabored Glory viciously over the jaws with it; silently except for the soft thud and slap of felt on flesh. And the mood of him was as near murder as Weary could come. Glory had been belabored with worse things than hats during his eventful career; he laid back his ears, shut his eyes tight and took it meekly.

There came a gasping gurgle from the hammock, and Weary’s hand stopped in mid-air. The girl’s head was burrowed in a pillow and her slippers tapped the floor while she laughed and laughed.

Weary delivered a parting whack, put on his hat and looked at her uncertainly; grinned sheepishly when the humor of the thing came to him slowly, and finally sat down upon the porch steps and laughed with her.

“Oh, gee! It was too funny,” gasped the girl, sitting up and wiping her eyes.

Weary gasped also, though it was a small matter—a common little word of three letters. In all the messages sent him by the schoolma’am, it was the precise, school-grammar wording of them which had irritated him most and impressed him insensibly with the belief that she was too prim to be quite human. The Happy Family had felt all along that they were artists in that line, and they knew that the precise sentences ever carried conviction of their truth. Weary mopped his perspiring face upon a white silk handkerchief and meditated wonderingly.

“You aren’t a train-robber or a horsethief, or—anything, are you?” she asked him presently. “You seemed quite upset at seeing the place wasn’t deserted; but I’m sure, if you are a robber running away from a sheriff, I’d never dream of stopping you. Please don’t mind me; just make yourself at home.”

Weary turned his head and looked straight up at her. “I’m afraid I’ll have to disappoint yuh, Miss Satterly,” he said blandly. “I’m just an ordinary human, and my name is Davidson—better known as Weary. You don’t appear to remember me. We’ve met before.”

She eyed him attentively. “Perhaps we have—it you say so. I’m wretched about remembering strange names and faces. Was it at a dance? I meet so many fellows at dances—” She waved a brown little hand and smiled deprecatingly.

“Yes,” said Weary laconically, still looking into her face. “It was.”

She stared down at him, her brows puckered. “I know, now. It was at the Saint Patrick’s dance in Dry Lake! How silly of me to forget.”

Weary turned his gaze to the hill beyond the creek, and fanned his hot face with his hat. “It was not. It wasn’t at that dance, at all.” Funny she didn’t remember him! He suspected her of trying to fool him, now that he was actually in her presence, and he refused absolutely to be fooled.

He could see that she threw out her hand helplessly. “Well, I may as well ’fess up. I don’t remember you at all. It’s horrid of me, when you rode up in that lovely, unconventional way. But you see, at dances one doesn’t think of the men as individuals; they’re just good or bad partners. It resolves itself, you see, into a question of feet. If I should dance with you again,—did I dance with you?”

Weary shot a quick, eloquent glance in her direction. He did not say anything.

Miss Satterly blushed. “I was going to say, if I danced with you again I should no doubt remember you perfectly.”

Weary was betrayed into a smile. “If I could dance in these boots, I’d take off my spurs and try and identify myself. But I guess I’ll have to ask yuh to take my word for it that we’re acquainted.”

“Oh, I will. I meant to, all along. Why aren’t you in town, celebrating? I thought I was the only unpatriotic person in the country.”

“I just came from town,” Weary told her, choosing, his words carefully while yet striving to be truthful. No man likes confessing to a woman that he has been run away with. “I—er—broke my bridle-bit, back a few miles” (it was fifteen, if it were a rod) “and so I rode in here to get one of Joe’s. I didn’t want to bother anybody, but Glory seemed to think this was where the trail ended.”

Miss Satterly laughed again. “It certainly was funny—you trying to get him away, and being so still about it. I heard you whispering swear-words, and I wanted to scream! I just couldn’t keep still any longer. Is he balky?”

“I don’t know what he is—now,” said Weary plaintively. “He was, at that time. He’s generally what happens to be the most dev—mean under the circumstances.”

“Well, maybe he’ll consent to being led to the stable; he looks as if he had a most unmerciful master!” (Weary, being perfectly innocent, blushed guiltily) “But I’ll forgive you riding him like that, and make for you a pitcher of lemonade and give you some cake while he rests. You certainly must not ride back with him so tired.”

Fresh lemonade sounded tempting, after that ride. And being lectured was not at all what he had expected from the schoolma’am—and who can fathom the mind of a man? Weary gave her one complex glance, laid his hand upon the bridle and discovered that Glory, having done what mischief he could, was disposed to be very meek. At the corral gate Weary looked back.

“At dances,” he mused aloud, “one doesn’t consider men as individuals—it’s merely a question of feet. She took me for a train robber; and I danced with her about forty times, that night, and took her over to supper and we whacked up on our chicken salad because there was only one dish for the two of us—oh, mamma!”

He pulled off the saddle with a preoccupied air and rubbed Glory down mechanically. After that he went over and sat down on the oats’ box and smoked two cigarettes while he pondered many things.

He stood up and thoughtfully surveyed himself, brushed sundry bright sorrel hairs from his coat sleeves, stooped and tried to pinch creases into the knees of his trousers, which showed symptoms of “bagging.” He took off his hat and polished it with his sleeve he had just brushed so carefully, pinched four big dimples in the crown, turned it around three times for critical inspection, placed it upon his head at a studiously unstudied angle, felt anxiously at his neck-gear and slapped Glory affectionately upon the rump—and came near getting kicked into eternity. Then he swung off up the path, softly whistling “In the good, old summer-time.” An old hen, hovering her chicks in the shade of the hay-rack, eyed him distrustfully and cried “k-r-r-r-r” in a shocked tone that sent her chickens burrowing deeper under her feathers.

Miss Satterly had changed her pink kimono for a white shirt-waist and had fluffed her hair into a smooth coil on the top of her head. Weary thought she looked very nice. She could make excellent lemonade, he discovered, and she proved herself altogether different from what the messages she sent him had led him to expect. Weary wondered, until he became too interested to think about it.

Presently, without quite knowing how it came about, he was telling her all about the race. Miss Satterly helped him reckon his winnings—which was not easy to do, since he had been offered all sorts of odds and had accepted them all with a recklessness that was appalling. While her dark head was bent above the piece of paper, and her pencil was setting down figures with precise little jabs, he watched her. He quite forgot the messages he had received from her through the medium of the Happy Family, and he quite forgot that women could hurt a man.

“Mr. Davidson,” she announced severely, when the figures had all been dabbed upon the paper, “You ought to have lost. It would be a lesson to you. I haven’t quite figured all your winnings, these six-to-ones and ten-to-ones and—and all that, take time to unravel. But you, yourself, stood to lose just three hundred and sixty-five dollars. Gee! but you cowboys are reckless.”

There was more that she said, but Weary did not mind. He had discovered that he liked to look at the schoolma’am. After that, nothing else was of much importance. He began to wish he might prolong his opportunity for looking.

“Say,” he said suddenly, “Come on and let’s go to the dance.”

The schoolma’am bit at her pencil and looked at him. “It’s late—”

“Oh, there’s time enough,” urged Weary.

“Maybe—but—”

“Do yuh think we aren’t well enough acquainted?”

“Well we’re not exactly old friends,” she laughed.

“We’re going to be, so it’s all the same,” Weary surprised himself by declaring with much emphasis. “You’d go, wouldn’t you, if I was—well, say your brother?”

Miss Satterly rested her chin in her palms and regarded him measuringly. “I don’t know. I never had one—except three or four that I—er—adopted, at one time or another. I suppose one could go, though—with a brother.”

Weary made a rapid, mental note for the benefit of the Happy Family—and particularly Cal Emmett. “Darling Brother” was a myth, then; he ought to have known it, all along. And if that were a myth, so probably were all those messages and things that he had hated. She didn’t care anything about him—and suddenly that struck him unpleasantly, instead of being a relief, as it consistently should have been.

“I wish you’d adopt me, just for to-night, and go;” he said, and his eyes backed the wish. “You see,” he added artfully, “it’s a sin to waste all that good music—a real, honest-to-God stringed orchestra from Great Falls, and—”

“Meekers have taken both rigs,” objected she, weakly.

“I noticed a side saddle hanging in the stable,” he wheedled, “and I’ll gamble I can rustle something to put it on. I—”

“I should think you’d gambled enough for one day,” she quelled. “But that chunky little gray in the pasture is the horse I always ride. I expect,” she sighed, “my new dancing dress would be a sight to behold when I got there—and it won’t wash. But what does a mere man care—”

“Wrap it up in something, and I’ll carry it for yuh,” Weary advised eagerly. “You can change at the hotel. It’s dead easy.” He picked up his hat from the floor, rose and stood looking anxiously down at her. “About how soon,” he insinuated, “can you be ready?”

The schoolma’am looked up at him irresolutely, drew a long breath and then laughed. “Oh, ten minutes will do,” she surrendered. “I shall put my new dress in a box, and go just as I am. Do you always get your own way, Mr. Davidson?”

“Always,” he lied convincingly over his shoulder, and jumped off the porch without bothering to use the steps.

She was waiting when he led the little gray up to the house, and she came down the steps with a large, flat, pasteboard box in her arms.

“Don’t get off,” she commanded. “I can mount alone—and you’ll have to carry the box. It’s going to be awkward, but you would have me go.”

Weary took the box and prudently remained in the saddle. Glory, having the man he did for master, was unused to the flutter of women’s skirts so close, and rolled his eyes till the whites showed all round. Moreover, he was not satisfied with that big, white thing in Weary’s arms.

He stood quite still, however, until the schoolma’am was settled to her liking in the saddle, and had tucked her skirt down over the toe of her right foot. He watched the proceeding with much interest—as did Weary—and then walked sedately from the yard, through the pebbly creek and up the slope beyond. He heard Weary give a sigh of relief at his docility, and straightway thrust his nose between his white front feet, and proceeded to carry out certain little plans of his own. Weary, taken by surprise and encumbered by the box, could not argue the point; he could only, in range parlance, “hang and rattle.”

“Oh,” cried Miss Satterly, “if he’s going to act like that, give me the box.”

Weary would like to have done so, but already he was half way to the gate, and his coat was standing straight out behind to prove the speed of his flight. He could not even look back. He just hung tight to the box and rode.

The little gray was no racer, but his wind was good; and with urging he kept the fleeing Glory in sight for a mile or so. Then, horse and rider were briefly silhouetted against the sunset as they topped a distant hill, and after that the schoolma’am rode by faith.

At the gate which led into the big Flying U field she overtook them. Glory, placid as a sheep, was nibbling a frayed end of the rope which held the gate shut, and Weary, the big box balanced in front of him across the saddle, was smoking a cigarette.