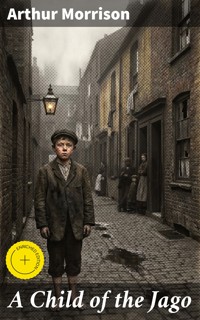

It

was past the mid of a summer night in the Old Jago. The narrow

street was all the blacker for the lurid sky; for there was a fire

in a farther part of Shoreditch, and the welkin was an infernal

coppery glare. Below, the hot, heavy air lay, a rank oppression, on

the contorted forms of those who made for sleep on the pavement:

and in it, and through it all, there rose from the foul earth and

the grimed walls a close, mingled stink—the odour of the

Jago.

From where, off Shoreditch High

Street, a narrow passage, set across with posts, gave menacing

entrance on one end of Old Jago Street, to where the other end lost

itself in the black beyond Jago Row; from where Jago Row began

south at Meakin Street, to where it ended north at Honey Lane—there

the Jago, for one hundred years the blackest pit in London, lay and

festered; and half-way along Old Jago Street a narrow archway gave

upon Jago Court, the blackest hole in all that pit.

A square of two hundred and fifty

yards or less—that was all there was of the Jago. But in that

square the human population swarmed in thousands. Old Jago Street,

New Jago Street, Half Jago Street lay parallel, east and west: Jago

Row at one end and Edge Lane at the other lay parallel also,

stretching north and south: foul ways all. What was too vile for

Kate Street, Seven Dials, and Ratcliff Highway in its worst day,

what was too useless, incapable and corrupt—all that teemed in the

Old Jago.

Old Jago Street lay black and

close under the quivering red sky; and slinking forms, as of great

rats, followed one another quickly between the posts in the gut by

the High Street, and scattered over the Jago. For the crowd about

the fire was now small, the police was there in force, and every

safe pocket had been tried. Soon the incursion ceased, and the sky,

flickering and brightening no longer, settled to a sullen flush. On

the pavement some writhed wearily, longing for sleep; others,

despairing of it, sat and lolled, and a few talked. They were not

there for lack of shelter, but because in this weather repose was

less unlikely in the street than within doors: and the lodgings of

the few who nevertheless abode at home were marked here and there

by the lights visible from the windows. For in this place none ever

slept without a light, because of three kinds of vermin that light

in some sort keeps at bay: vermin which added to existence here a

terror not to be guessed by the unafflicted: who object to being

told of it. For on them that lay writhen and gasping on the

pavement; on them that sat among them; on them that rolled and

blasphemed in the lighted rooms; on every moving creature in this,

the Old Jago, day and night, sleeping and walking, the third plague

of Egypt, and more, lay unceasing.

The stifling air took a further

oppression from the red sky. By the dark entrance to Jago Court a

man rose, flinging out an oath, and sat with his head bowed in his

hands.

'Ah—h—h—h,' he said. 'I wish I

was dead: an' kep' a cawfy shop.' He looked aside from his hands at

his neighbours; but Kiddo Cook's ideal of heaven was no new thing,

and the sole answer was a snort from a dozing man a yard

away.

Kiddo Cook felt in his pocket and

produced a pipe and a screw of paper. 'This is a bleed'n' unsocial

sort o' evenin' party, this is,' he said, 'An' 'ere's the on'y real

toff in the mob with ardly 'arf a pipeful left, an' no lights. D'

y' 'ear, me lord'—leaning toward the dozing neighbour—'got a

match?'

'Go t' 'ell!'

'O wot 'orrid langwidge! It's

shocking, blimy. Arter that y' ought to find me a match. Come

on.'

'Go t' 'ell!'

A lank, elderly man, who sat with

his back to the wall, pushed up a battered tall hat from his eyes,

and, producing a box of matches, exclaimed 'Hell? And how far's

that? You're in it!' He flung abroad a bony hand, and glanced

upward. Over his forehead a greasy black curl dangled and shook as

he shuddered back against the wall. 'My God, there can be no hell

after this!'

'Ah,' Kiddo Cook remarked, as he

lit his pipe in the hollow of his hands, 'that's a comfort, Mr

Beveridge, any'ow.' He returned the matches, and the old man,

tilting his hat forward, was silent.

A woman, gripping a shawl about

her shoulders, came furtively along from the posts, with a man

walking in her tracks—a little unsteadily. He was not of the Jago,

but a decent young workman, by his dress. The sight took Kiddo

Cook's idle eye, and when the couple had passed, he said

meditatively: 'There's Billy Leary in luck ag'in: 'is missis do

pick 'em up, s'elp me. I'd carry the cosh meself if I'd got a woman

like 'er.'

Cosh-carrying was near to being

the major industry of the Jago. The cosh was a foot length of iron

rod, with a knob at one end, and a hook (or a ring) at the other.

The craftsman, carrying it in his coat sleeve, waited about dark

staircase corners till his wife (married or not) brought in a well

drunken stranger: when, with a sudden blow behind the head, the

stranger was happily coshed, and whatever was found on him as he

lay insensible was the profit on the transaction. In the hands of

capable practitioners this industry yielded a comfortable

subsistence for no great exertion. Most, of course, depended on the

woman: whose duty it was to keep the other artist going in

subjects. There were legends of surprising ingatherings achieved by

wives of especial diligence: one of a woman who had brought to the

cosh some six-and-twenty on a night of public rejoicing. This was,

however, a story years old, and may have been no more than an

exemplary fiction, designed, like a Sunday School book, to convey a

counsel of perfection to the dutiful matrons of the Old Jago.

The man and woman vanished in a

doorway near the Jago Row end, where, for some reason, dossers were

fewer than about the portal of Jago Court. There conversation

flagged, and a broken snore was heard. It was a quiet night, as

quietness was counted in the Jago; for it was too hot for most to

fight in that stifling air—too hot to do more than turn on the

stones and swear. Still the last hoarse yelps of a combat of women

came intermittently from Half Jago Street in the further

confines.

In a little while something large

and dark was pushed forth from the door-opening near Jago Row which

Billy Leary's spouse had entered. The thing rolled over, and lay

tumbled on the pavement, for a time unnoted. It might have been yet

another would-be sleeper, but for its stillness. Just such a thing

it seemed, belike, to two that lifted their heads and peered from a

few yards off, till they rose on hands and knees and crept to where

it lay: Jago rats both. A man it was; with a thick smear across his

face, and about his head the source of the dark trickle that sought

the gutter deviously over the broken flags. The drab stuff of his

pockets peeped out here and there in a crumpled bunch, and his

waistcoat gaped where the watch-guard had been. Clearly, here was

an uncommonly remunerative cosh—a cosh so good that the boots had

been neglected, and remained on the man's feet. These the kneeling

two unlaced deftly, and, rising, prize in hand, vanished in the

deeper shadow of Jago Row.

A small boy, whom they met full

tilt at the corner, staggered out to the gutter and flung a veteran

curse after them. He was a slight child, by whose size you might

have judged his age at five. But his face was of serious and

troubled age. One who knew the children of the Jago, and could

tell, might have held him eight, or from that to nine.

He replaced his hands in his

trousers pockets, and trudged up the street. As he brushed by the

coshed man he glanced again toward Jago Row, and, jerking his thumb

that way, 'Done 'im for 'is boots,' he piped. But nobody marked him

till he reached Jago Court, when old Beveridge, pushing back his

hat once more, called sweetly and silkily, 'Dicky Perrott!' and

beckoned with his finger.

The boy approached, and as he did

so the man's skeleton hand suddenly shot out and gripped him by the

collar. 'It—never—does—to—see—too—much!' Beveridge said, in a

series of shouts, close to the boy's ear. 'Now go home,' he added,

in a more ordinary tone, with a push to make his meaning plain: and

straightway relapsed against the wall.

The boy scowled and backed off

the pavement. His ragged jacket was coarsely made from one much

larger, and he hitched the collar over his shoulder as he shrank

toward a doorway some few yards on. Front doors were used merely as

firewood in the Old Jago, and most had been burnt there many years

ago. If perchance one could have been found still on its hinges, it

stood ever open and probably would not shut. Thus at night the Jago

doorways were a row of black holes, foul and forbidding.

Dicky Perrott entered his hole

with caution, for anywhere, in the passage and on the stairs,

somebody might be lying drunk, against whom it would be unsafe to

stumble. He found nobody, however, and climbed and reckoned his way

up the first stair-flight with the necessary regard for the treads

that one might step through and the rails that had gone from the

side. Then he pushed open the door of the first-floor back and was

at home.

A little heap of guttering

grease, not long ago a candle end, stood and spread on the

mantel-piece, and gave irregular light from its drooping wick. A

thin-railed iron bedstead, bent and staggering, stood against a

wall, and on its murky coverings a half-dressed woman sat and

neglected a baby that lay by her, grieving and wheezing. The woman

had a long dolorous face, empty of expression and weak of

mouth.

'Where 'a' you bin, Dicky?' she

asked, rather complaining than asking. 'It's sich low hours for a

boy.'

Dicky glanced about the room.

'Got anythink to eat?' he asked.

'I dunno,' she answered

listlessly. 'P'raps there's a bit o' bread in the cupboard. I don't

want nothin', it's so 'ot. An' father ain't bin 'ome since

tea-time.'

The boy rummaged and found a

crust. Gnawing at this, he crossed to where the baby lay. ''Ullo,

Looey,' he said, bending and patting the muddy cheek.

''Ullo!'

The baby turned feebly on its

back, and set up a thin wail. Its eyes were large and bright, its

tiny face was piteously flea-bitten and strangely old. 'Wy, she's

'ungry, mother,' said Dicky Perrott, and took the little thing

up.

He sat on a small box, and rocked

the baby on his knees, feeding it with morsels of chewed bread. The

mother, dolefully inert, looked on and said: 'She's that backward

I'm quite wore out; more 'n ten months old, an' don't even crawl

yut. It's a never-endin' trouble, is children.'

She sighed, and presently

stretched herself on the bed. The boy rose, and carrying his little

sister with care, for she was dozing, essayed to look through the

grimy window. The dull flush still spread overhead, but Jago Court

lay darkling below, with scarce a sign of the ruinous back yards

that edged it on this and the opposite sides, and nothing but

blackness between.

The boy returned to his box, and

sat. Then he said: 'I don't s'pose father's 'avin' a sleep outside,

eh?'

The woman sat up with some show

of energy. 'Wot?' she said sharply. 'Sleep out in the street like

them low Ranns an' Learys? I should 'ope not. It's bad enough

livin' 'ere at all, an' me being used to different things once, an'

all. You ain't seen 'im outside, 'ave ye?'

'No, I ain't seen 'im: I jist

looked in the court.' Then, after a pause: 'I 'ope 'e's done a

click,' the boy said.

His mother winced. 'I dunno wot

you mean, Dicky,' she said, but falteringly. 'You—you're gittin'

that low an' an'—'

'Wy, copped somethink, o' course.

Nicked somethink. You know.'

'If you say sich things as that

I'll tell 'im wot you say, an' 'e'll pay you. We ain't that sort o'

people, Dicky, you ought to know. I was alwis kep' respectable an'

straight all my life, I'm sure, an'—'

'I know. You said so before, to

father—I 'eard: w'en 'e brought 'ome that there yuller prop—the

necktie pin. Wy, where did 'e git that? 'E ain't 'ad a job for

munse and munse: where's the yannups come from wot's bin for to pay

the rent, an' git the toke, an' milk for Looey? Think I dunno? I

ain't a kid. I know.'

'Dicky, Dicky! you mustn't say

sich things!' was all the mother could find to say, with tears in

her slack eyes. 'It's wicked an'—an' low. An' you must alwis be

respectable an' straight, Dicky, an' you'll—you'll git on

then.'

'Straight people's fools, I

reckon. Kiddo Cook says that, an' 'e's as wide as Broad Street.

W'en I grow up I'm goin' to git toffs' clo'es an' be in the 'igh

mob. They does big clicks.'

'They git put in a dark prison

for years an' years, Dicky—an'—an' if you're sich a wicked low boy,

father 'll give you the strap—'ard,' the mother returned, with what

earnestness she might. 'Gimme the baby, an' you go to bed, go on;

'fore father comes.'

Dicky handed over the baby, whose

wizen face was now relaxed in sleep, and slowly disencumbered

himself of the ungainly jacket, staring at the wall in a brown

study. 'It's the mugs wot git took,' he said, absently. 'An'

quoddin' ain't so bad.' Then, after a pause, he turned and added

suddenly: 'S'pose father'll be smugged some day, eh, mother?'

His mother made no reply, but

bent languidly over the baby, with an indefinite pretence of

settling it in a place on the bed. Soon Dicky himself, in the short

and ragged shirt he had worn under the jacket, burrowed head first

among the dingy coverings at the foot, and protruding his head at

the further side, took his accustomed place crosswise at the

extreme end.