3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

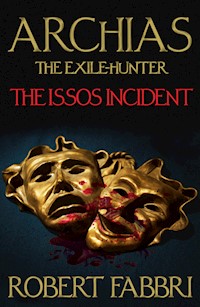

An Archias the Exile-Hunter short story Archias, struggling actor, quick on his feet and even faster with his words, is at the end of his luck. Having escaped to Rhosos, on the edge of Macedon's territory, to evade the threat of the debt collectors, he has been prevented from going any further by the arrival of Alexander the Great's mighty army. And with it, those very same debt collectors. So when the chance is given to him to earn enough money to be rid of his pursuers forever, he has to take it. Even if it means risking life and limb by attempting the most crazy of rescues - to bring back a kidnapped boy from inside the camp of Darius, King of Kings of the crumbling Persian empire. A camp that is on the eve of battle... As Alexander's troops draw nearer, and Darius's cavalry begin their war-cry, can Archias save himself, the boy, and his fellow rescuers, before it's too late?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

The Issos Incident

An Archias the Exile-Hunter short story

Robert Fabbri

Also by Robert Fabbri

Alexander's Legacy

To the Strongest

The Three Paradises

The Vespasian Series

Tribune of Rome

Rome's Executioner

False God of Rome

Rome's Fallen Eagle

Masters of Rome

Rome's Lost Son

The Furies of Rome

Rome's Sacred Flame

Emperor of Rome

Magnus and the Crossroads Brotherhood

Stand-alone novels

Arminius - the Limits of Empire

Published in e-book in Great Britain in 2021 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Robert Fabbri, 2021

The moral right of Robert Fabbri to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 9781838952945

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

The Issos Incident

‘So, old friends, what truths will we discover together this morning?’ Archias held two theatrical masks before him, contemplating the roles he was due to play in the rendering of Aeschylus’ tragedy The Eumenides. Carved of cedar, eyes wide and mouths open, gurning downwards, they could not be described as objects of beauty, but to Archias they were the most pleasing of sights. They were the instruments of his art. One, white faced with rouged cheeks, lips and eyelids, and raven hair piled high and tied in a bow, a couple of curled locks falling to either side, represented the dead Clytemnestra whose ghost comes from Hades to find the Furies asleep rather than hounding her matricidal son, Orestes. The second, Orestes’ embodiment, was as colourful but more masculine: a cascade of brown ringlets fell from a high forehead to frame a round face whose staring eyes were accentuated by triangles of black paint to either side of a long and prominent nose, meeting at its bridge. Along with the downturned, gaping mouth, his expression was one of constant and heightened worry. Very suitable for a man who has killed his mother and is being hunted by the Furies, the female chthonic deities of vengeance, Archias mused, the poetry he would declaim running through his mind.

He smiled at the beauty of the language and the enjoyment that it would give him as he delivered his lines on the stage, facing a towering audience in the high, semi-circular theatron. He had been enamoured of the spoken word since his first utterances. It had been this love of language that had persuaded his reasonably well-to-do parents to send him from his native Thurii, one of the Greek colonies in far-off southern Italia, to study rhetoric under Anaximenes of Lampsacus in Athens, as well as the music, athletics and arithmetic taught by the sophist Lacritus. When Anaximenes had received the summons from Philip, King of Macedon, to go north to Pella to aid Aristotle in the training of the heir to the throne, Alexander, Archias gave up his studies, for he had developed a passion for the theatre and spent all his free time – and much of his meagre allowance – watching plays during the many festivals of the Athenian calendar. With his trained voice he was soon taken into the chorus of one of the more prestigious companies that vied for work in Athens and beyond; he was quick to learn his trade and, with his encyclopaedic memory, in a short while had most of the tragic canon at his command. He rose from the chorus to become the main actor of the company and then, after a few years and a stint of compulsory military service, its manager as well.

But that had been seven years ago, and whilst he enjoyed his work, he had failed to make any significant amount of money through it. To be blunt, he was in his early thirties and heavily in debt – a struggling actor. And so he sat, in the theatre at Rhosos, overlooking the port, in what had been the Persian satrapy of Cilicia, contemplating his masks and waiting for the performance to begin. The parallels between the hunted Orestes and himself were painfully obvious, for although it was not the three Furies who pursued him, his creditors were equally as fearsome and, being seven in number, more numerous.

However, the world was changing and the evidence of that was to be seen in the theatron. Not for the first time in Archias’ experience of playing in the Greek cities of the crumbling Persian empire, there were no Persians in the audience; it was made up mainly of Macedonian and Greek officers. In just a few months, Alexander had led his army across the Hellespont, south along its coast, up through central Anatolia, back down to Tarsus and then south, here, to Rhosos and then on to face Darius’ army at Myriandrus on the Syrian border. But a great storm had prevented contact and the armies had moved apart. Now Alexander’s was encamped north of Rhosos, between the coast and the Amanus Mountains.

It had been chance that had brought Archias to the city – chance or, perhaps, fate – at the same time as the Macedonian advance. He had been touring his company, consisting of him and two other actors – all equally anxious to be away from Athens for a good while – south along the coast since his arrival in Ephesus at the beginning of the sailing season, eighteen months previously. His arrival had coincided with Alexander bringing his army across the Hellespont. For a time, Archias had followed the Macedonians along the Anatolian coast, taking advantage of the business they brought. However, when Alexander had turned his army back north, Archias had decided not to head inland with it but remain, instead, on the more Greek-oriented seaboard. But now Alexander had caught up with him again.