0,91 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Seltzer Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

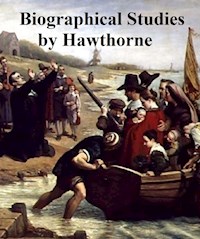

The biographies (from the collection "Fanshawe and Other Pieces") are: Mrs. Hutchinson, Sir William Phips, Sir William Pepperell, Thomas Green Fessenden, and Jonathan Cilley. According to Wikipedia: ""Nathaniel Hawthorne (born Nathaniel Hathorne; July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer."

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 84

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

BIOGRAPHICAL STUDIES FROM: FANSHAWE AND OTHER PIECES BY NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE

published by Samizdat Express, Orange, CT, USA

established in 1974, offering over 14,000 books

Non-Fiction by Nathaniel Hawthorne --

Passages From The American Note-Books Of Nathaniel Hawthorne

Passages From The English Note-Books Of Nathaniel Hawthorne

Passages From The French And Italian Note-Books Of Nathaniel Hawthorne

Biographical Studies From: Fanshawe And Other Pieces

True Stories Of History And Biography

Sketches And Studies

Our Old Home A Series Of English Sketches

Journal of an

A

frican

C

ruiser

The Whole History Of Grandfather's Chair Or True Stories From New England History, 1620-1808

feedback welcome: [email protected]

visit us at samizdat.com

Mrs. Hutchinson

Sir William Phips

Sir William Pepperell.

Thomas Green Fessenden

Jonathan Cilley

MRS. HUTCHINSON.

The character of this female suggests a train of thought which will form as natural an Introduction to her story, as most of the Prefaces to Gay's Fables, or the tales of Prior; besides that, the general soundness of the moral may excuse any want of present applicability. We will not look for a living resemblance of Mrs. Hutchinson, though the search might not be altogether fruitless. But there are portentous indications, changes gradually taking place in the habits and feelings of the gentle sex, which seem to threaten our posterity with many of those public women, whereof one was a burden too grievous for our fathers. The press, however, is now the medium through which feminine ambition chiefly manifests itself; and we will not anticipate the period (trusting to be gone hence ere it arrive) when fair orators shall be as numerous as the fair authors of our own day. The hastiest glance may show how much of the texture and body of cisatlantic literature is the work of those slender fingers from which only a light and fanciful embroidery has heretofore been required, that might sparkle upon the garment without enfeebling the web. Woman's intellect should never give the tone to that of man; and even her morality is not exactly the material for masculine virtue. A false liberality, which mistakes the strong division-lines of Nature for arbitrary distinctions, and a courtesy, which might polish criticism, but should never soften it, have done their best to add a girlish feebleness to the tottering infancy of our literature. The evil is likely to be a growing one. As yet, the great body of American women are a domestic race; but when a continuance of ill-judged incitements shall have turned their hearts away from the fireside, there are obvious circumstances which will render female pens more numerous and more prolific than those of men, though but equally encouraged; and (limited, of course, by the scanty support of the public, but increasing indefinitely within those limits) the inkstained Amazons will expel their rivals by actual pressure, and petticoats wave triumphantly over all the field. But, allowing that such forebodings are slightly exaggerated, is it good for woman's self that the path of feverish hope, of tremulous success, of bitter and ignominious disappointment, should be left wide open to her? Is the prize worth her having, if she win it? Fame does not increase the peculiar respect which men pay to female excellence, and there is a delicacy (even in rude bosoms, where few would think to find it) that perceives, or fancies, a sort of impropriety in the display of woman's natal mind to the gaze of the world, with indications by which its inmost secrets may be searched out. In fine, criticism should examine with a stricter, instead of a more indulgent eye, the merits of females at its bar, because they are to justify themselves for an irregularity which men do not commit in appearing there; and woman, when she feels the impulse of genius like a command of Heaven within her, should be aware that she is relinquishing a part of the loveliness of her sex, and obey the inward voice with sorrowing reluctance, like the Arabian maid who bewailed the gift of prophecy. Hinting thus imperfectly at sentiments which may be developed on a future occasion, we proceed to consider the celebrated subject of this sketch.

Mrs. Hutchinson was a woman of extraordinary talent and strong imagination, whom the latter quality, following the general direction taken by the enthusiasm of the times, prompted to stand forth as a reformer in religion. In her native country, she had shown symptoms of irregular and daring thought, but, chiefly by the influence of a favorite pastor, was restrained from open indiscretion. On the removal of this clergyman, becoming dissatisfied with the ministry under which she lived, she was drawn in by the great tide of Puritan emigration, and visited Massachusetts within a few years after its first settlement. But she bore trouble in her own bosom, and could find no peace in this chosen land. She soon began to promulgate strange and dangerous opinions, tending, in the peculiar situation of the colony, and from the principles which were its basis, and indispensable for its temporary support, to eat into its very existence. We shall endeavor to give a more practical idea of this part of her course.

It is a summer evening. The dusk has settled heavily upon the woods, the waves, and the Trimountain peninsula, increasing that dismal aspect of the embryo town, which was said to have drawn tears of despondency from Mrs. Hutchinson, though she believed that her mission thither was divine. The houses, straw thatched and lowly roofed, stand irregularly along streets that are yet roughened by the roots of the trees, as if the forest, departing at the approach of man, had left its reluctant footprints behind. Most of the dwellings are lonely and silent: from a few we may hear the reading of some sacred text, or the quiet voice of prayer; but nearly all the sombre life of the scene is collected near the extremity of the village. A crowd of hooded women, and of men in steeple-hats and close-cropped hair, are assembled at the door and open windows of a house newly built. An earnest expression glows in every face; and some press inward, as if the bread of life were to be dealt forth, and they feared to lose their share; while others would fain hold them back, but enter with them, since they may not be restrained. We, also, will go in, edging through the thronged doorway to an apartment which occupies the whole breadth of the house. At the upper end, behind a table, on which are placed the Scriptures and two glimmering lamps, we see a woman, plainly attired, as befits her ripened years: her hair, complexion, and eyes are dark, the latter somewhat dull and heavy, but kindling up with a gradual brightness. Let us look round upon the hearers. At her right hand his countenance suiting well with the gloomy light which discovers it, stands Vane, the youthful governor, preferred by a hasty judgment of the people over all the wise and hoary heads that had preceded him to New England. In his mysterious eyes we may read a dark enthusiasm, akin to that of the woman whose cause he has espoused, combined with a shrewd worldly foresight, which tells him that her doctrines will be productive of change and tumult, the elements of his power and delight. On her left, yet slightly drawn back, so as to evince a less decided support, is Cotton, no young and hot enthusiast, but a mild, grave man in the decline of life, deep in all the learning of the age, and sanctified in heart, and made venerable in feature, by the long exercise of his holy profession. He, also, is deceived by the strange fire now laid upon the altar; and he alone among his brethren is excepted in the denunciation of the new apostle, as sealed and set apart by Heaven to the work of the ministry. Others of the priesthood stand full in front of the woman, striving to beat her down with brows of wrinkled iron, and whispering sternly and significantly among themselves as she unfolds her seditious doctrines, and grows warm in their support. Foremost is Hugh Peters, full of holy wrath, and scarce containing himself from rushing forward to convict her of damnable heresies. There, also, is Ward, meditating a reply of empty puns, and quaint antitheses, and tinkling jests that puzzle us with nothing but a sound. The audience are variously affected; but none are indifferent. On the foreheads of the aged, the mature, and strong-minded, you may generally read steadfast disapprobation, though here and there is one whose faith seems shaken in those whom lie had trusted for years. The females, on the other hand, are shuddering and weeping, and at times they cast a desolate look of fear around them; while the young men lean forward, fiery and impatient, fit instruments for whatever rash deed may be suggested. And what is the eloquence that gives rise to all these passions? The woman tells then (and cites texts from the Holy Book to prove her words) that they have put their trust in unregenerated and uncommissioned men, and have followed them into the wilderness for nought. Therefore their hearts are turning from those whom they had chosen to lead them to heaven; and they feel like children who have been enticed far from home, and see the features of their guides change all at once, assuming a fiendish shape in some frightful solitude.