Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Carcanet Poetry

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

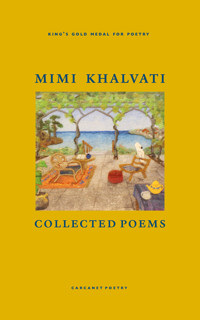

King's Gold Medal for Poetry Winner of the Jhalak Poetry Prize 2025 A Guardian Book of the Year 2024 A London Review Bookshop Book of the Year 2024 Mimi Khalvati, one of our best-loved poets, was born in Tehran, Iran, and sent away to boarding school on the Isle of Wight at the age of six, only returning to her family in Iran when she was seventeen. The loss of her native country, culture and mother tongue formed the bedrock of her adoptive love of the English language and its lyric tradition. 'But,' she says, 'whether drawing on my few memories of Iran, my long years in London and travelling in the Mediterranean, or on that central void always facing me, I have celebrated the richness of a life that can be lived without a clear sense of heritage, family history or personal biography.' That wealth is reflected in the wide variety of style, tone and architecture in her Carcanet poetry collections over thirty-three years – free and metrical verse, ranging from short, fixed forms to extended lyrical sequences, from ghazals to the heroic corona or book-length series of sonnets. 'I hope', she writes, 'the poems speak especially to those who have made their homes wherever the tide has brought them, sometimes in language itself, and to those who have no story but place their trust in the flux and flow, the vision of the lyric moment.'

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 439

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

COLLECTED POEMS

Mimi Khalvati was born in Tehran, Iran, and grew up on the Isle of Wight. She has lived most of her life in London. After training at Drama Centre London, she worked as an actor in the UK and as a director at the Theatre Workshop Tehran and on the fringe in London. She has published nine poetry collections with Carcanet Press, including The Meanest Flower, shortlisted for the T.S.Eliot Prize 2007, Child: New and Selected Poems 1991-2011, a Poetry Book Society Special Commendation, The Weather Wheel, a PBS Commendation and a book of the year in The Independent, and Afterwardness, a book of the year in The Sunday Times and The Guardian. She was a co-winner of the Poetry Business Pamphlet Competition 1989 and her Very Selected Poems appeared from Smith/Doorstop in 2017. She has been Poet in Residence at the Royal Mail and has held fellowships at the International Writing Program in Iowa as the recipient of the William B. Quarton International Writing Program Scholarship, at the American School in London and at the Royal Literary Fund, City University. She is the founder of The Poetry School and has co-edited its three anthologies of new writing published by Enitharmon Press. Her awards include a Cholmondeley Award from the Society of Authors, a major Arts Council Award and she is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and of The English Society. In 2023 she was awarded the King’s Gold Medal for Poetry.

Every effort has been made by the publisher to reproduce the formatting of the original print edition in electronic format. However, poem formatting may change according to reading device and font size.

First published in Great Britain in 2024 by Carcanet Press Ltd, Alliance House, 30 Cross Street, Manchester M2 7AQ.

This new eBook edition first published in 2024.

Cover image © Christina Edlund-Plater.

Text copyright © Mimi Khalvati, 2024. The Right of Mimi Khalvati to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act of 1988; all rights reserved.

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publisher, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Ebook ISBN: 978 1 80017 334 7

The publisher acknowledges financial assistance from Arts Council England.

CONTENTS

In White Ink (1991)

Woman, Stone and Book

The Woman in the Wall

Amanuensis

Stone of Patience

Family Footnotes

Shanklin Chine

Sick Boy

Blue Moon

Confusing Arrivals with Departures

In Search of Melodrama

The Poulterer

‘You must learn to murder your darlings’

A ‘Post-Feminist’ Dawn

The Waiting House

Jasmine

Rooming

No Matter

In Lieu of a Postcard

Reflections

La Belle Dame

A Thank-You Letter

Turning the Page

Evergreen

The Bowl

A Persian Miniature

Rubaiyat

Rice

Haiku

Earls Court

Baba Mostafa

Christmas Greetings

Whittington Hospital, March 1990

The Promenade

The Black and White Cows

Acorns

‘The poppy signals time to scythe the wheat’

Plant Care

Mirrorwork (1995)

Mirrorwork

Vine-Leaves

Au Jardin du Luxembourg

Coma

What Seemed so Quiet

Sandpits

Deer Dreaming

Boy in a Photograph

The North-Facing Garden

Writing in the Sun

Prayer

Interiors

Needlework

That Night, at the Jazz Café

On Reading Rumi

Geraniums

Love

The Deer’s Eye

Reaching the Midway Mark

The Face

Christopher on Foot

Apology

A View of Courtyards

Entries on Light (1997)

Knocking on the door you open

Sunday. I woke from a raucous night

Today’s grey light

Scales are evenly weighed

Streetlamps threw battlements

The heavier, fuller, breast and body grow

Through me light drives on seawall

In the amber

The air is the hide of a white bull

I’m silenced in

I hear myself in the loudness of overbearing waves

Speak to me as shadows do

This book is a seagull whose wings you hold

I’m opening the door of shadow

One upper pane by a windchime

I’ve never been in a hurry

It’s all very well

Show, show me

: that sky and light and colour

I love all things in miniature

In that childhood time

Light’s taking a bath tonight

Dawn paves its own way

With finest needles

When sky paints itself

There’s no jewel we can think of

Moons come in all the colours

Why not mention the purple flower

One sky is a canvas for jets and vapour trails

Black fruit is sweet, white is sweeter

They go right through you, smells

He’s tying up the gypsophila

And had we ever lived in my country

Winter’s strains

And in the sea’s blackness sank

When space is at its emptiest

Was it morning, night?

Curling her tail

His 18th. He likes Chinese

Staring up from his pram to the sky

New Year’s Eve

In this country

Here’s dusk to burrow in

All yellow has gone from the day

While the tulip threatens to lose one leaf

Even if I never said

Darling, your message on the phone

Is it before or after the fiesta?

On a late summer’s day that draws to a close

First you invite me to tea under your appletree

Everywhere you see her

Don’t draw back

Light comes between us and our grief

Why does the aspen tremble

Boys have been throwing stones all day

Foreshortened, light claws out of the sea

On a diving-board

These hills are literally blue

I have removed the scaffolding

So high up in a house

These homes in poems

For those who have no homes like these

For you, who are a large man

When against a cloth

The gate has five bars

I’m reading with the light on

Times are – thinking about new wine

Like old red gold

An Iranian professor I know asked me

I’ve always grown in other people’s shade

…Human beings must be taught to love

Nothing can ruin the evening

It’s the eye of longing that I tire of

To be so dependent on sunlight

What is he looking for

It lives in crystal, flame

As wave comes in on wave

It is said God created a peacock of light

Too much light is tiresome

Light’s sharpening knives of water

I’ve stored all the light I need

I loved you so much

Air’s utterly soft

And suppose I left behind

‘Going away’

Finally, in a cove

It can come from the simplest of things

The Chine (2002)

The Chine

The Rain Chapel

Writing Letters

Nostalgia

The Alder Leaf

Writing Home

Holiday Homes

Sadness

All Things Bright and Beautiful

Childhood Books

Lyric

Simorgh

Listening to Strawberry

Middle Age

River Sonnet

Gooseberries

The Inwardness of Elephants

The Wishing Tree

Silhouettes

Mammont

Elephant Man

White Gold

Buddha

Literature

Darling

The Wedding

Mahout

Villanelle

The Piano

Winter Dawn

Terrapin

The Event

Babies

Il Bacio Deli

The Suzuki Method

Eden

Life in Art

Snails

The Fabergé Egg

The Love Barn

The Coat

Just to Say

Moving the Bureau

Song

Tenderness

Love in an English August

Ghazal: Who’d Argue?

Don’t Ask Me, Love, for that First Love

The Meanest Flower (2007)

The Meanest Flower

Ghazal: It’s Heartache

Ghazal: Lilies of the Valley

Ghazal: The Candles of the Chestnut Trees

Ghazal after Hafez

Ghazal: To Hold Me

Ghazal: Of Ghazals

The Mediterranean of the Mind

The Middle Tone

Al Fresco

Scorpion-grass

Water Blinks

The Valley

Overblown Roses

Come Close

Soapstone Creek

Soapstone Retreat

On a Line from Forough Farrokhzad

Impending Whiteness

Amy’s Horse

The Year of the Dish

Motherhood

The Robin and the Eggcup

Song for Springfield Park

On Lines from Paul Gauguin

Magpies

Ghazal: The Servant

Ghazal: The Children

Ghazal: My Son

Signal

Sundays

Tintinnabuli

from Child: New and Selected Poems 1991-2011

Iowa Daybook

The Streets of La Roue

Afterword

Night Sounds

River Sounding

Cretan Cures

The Poet’s House

The Weather Wheel (2014)

House Mouse

Madame Berthe’s Mouse Lemur

Sun Sparrow

Knifefish

Snail

Sciurus Carolinensis

The Conservatory

The Little Gloster

Microchiroptera

The Landing Stage

Earthshine

Prunus Avium

Under the Vine

Starlight

Angels

Orchard

What it Was

Marrakesh I–VI

Le Café Marocain

New Year’s Eve

The Pear Tree

Rain Stories

Aunt Moon

Statham Grove Surgery

The Wardrobe

Fog

Snow is

The Blanket

The Swarm

Model for a Timeless Garden

The Soul Travels on Horseback

The Overmind

Reading the Saturday Guardian

Midsummer Solstice

Picking Raspberries with Mowgli

Sniff

Drawing Bea

Nocturne

The Waves

Similes

Cherries and Grapes

Kusa-Hibari

Tears

The Goat

On the Occasion of his 150th Anniversary

In Search of the Animals

Martina’s Radiance

Mehregan

Sun in the Window

Bringing Down the Stars

The Cloud Sarcophagus

The Doe

Abney Park Cemetery

Migration

Her Anniversary

Granadilla de Abona I–VII

Plaza de los Remedios

The Wheelhouse

Finca El Tejado

The Avenue

Ghazal: In Silence

Afterwardness (2019)

Questions

Translation

Handwriting

Dictation

Elocution

Background Music

Background Music (ii)

Dreamers

Afterwardness

Scripto Inferior

Cafés

Jolanta

The Brag

Hide and Seek

The Introvert House

Outpatients

Villajoyosa

The Boy

Dysphagia

The Artist as a Child

The Lesser Brethren

Torbay

Maria

Old Stamping Grounds

Chamaeleonidae

The Colours My Mother Wore

My Mother’s Lighter

My Mother’s Portrait

The Courtyard

Twelve

Very

Bush Cricket

Reading under Trees

Postcard from Crete

The Street

Friends House

The Older Reader

The Living Room

Life Writing

Eggs

September

The Ice Rink

In Praise of the Sestet

Night Writing

‘Petites Salissures’

One Summer Holiday

Facades

Physiognomy

Smiles

Homa

My Sixth Birthday Party

Junior School Production

Azarinejad and Bear

Mehrabad Airport

Mehrabad Airport (ii)

Vapour Trails

Uncollected Poems

Malih at St Mary’s

The Playground

The Barge

Autumn Equinox

In the Goosehouse

We Stop to Finger the…

Spelling Katherine

Zereshk Polow

The Kurdish Musician

The Drought Garden

Snowdrops

Photo of the Poet

Triple Bypass

The Dark Side of the Moon

Glose: The Summer of Love

Blessing

Ghazal

Wedding Vow

Hearing Voices

Spartacus on Loop

What Kind of Tiger?

The Lie

One Day

The Wasp Nest

Notes

Acknowledgements

Index

for

Maitreyabandhu

IN WHITE INK (1991)

‘In women’s speech, as in their writing, that element which never stops resonating … is the song: first music from the first voice of love which is alive in every woman … A woman is never far from “mother” (… as nonname and as source of goods.) There is always within her at least a little of that good mother’s milk. She writes in white ink.’

– Hélène Cixous, The Laugh of the Medusa

WOMAN, STONE AND BOOK

And I woke one night

in tears from a terrible dream

of a small stone house

with a central chimney, a spiral

staircase and grapes on the windowsill.

I later learnt: you are describing

a peasant cottage of the sixteenth century

to be found all over Europe – France,

Poland, Germany. That puts a different

slant on it. The hologram again

adjusting angles of vision receding

into history asserting the right

to unfold itself, perhaps being

itself a section, a skin some godly

presence is peering in to learn

something of what it is to be human.

And I woke one night

in tears from a terrible dream

where I said to the old woman writer

beside me I’ve been here before.

For some strange reason

the woman’s name was Katherine.

Katherine? What does Katherine

mean to you? Katherine Mansfield

was the only name that came to me.

I lived in a house called Mansfield Place,

a small brick cottage in peachy pink

where my children were raised,

a spiral staircase painted blue

holding faces adjusting angles

to my line of vision. I was the big one

in those years. From the turn of the stair

that one about Tom when he was little:

Tom fly he yelled and he flew,

landing on my back in the hall

bending to pick up wellingtons.

Accidents of life preserving it?

Or patterns’ interferences, mute

as the backs of angels who break men’s fall?

And I had been there before in dreams,

playing games of hide and seek

through currant bushes and neighbours’

gardens, forgetting now what I was

searching for if I knew it then.

Something to do with infidelity

I think. In those years these were

things we suffered from, with our hands

in each others’ pockets striving

to become one skin. Letting go,

struggling now to fill our own.

And I asked myself

why are you crying and answered

I am forty-three and have understood

in a dream of woman, stone and book

what all those people mean

and why they mourn

and how clean I have been

through all those years of innocence.

Two camps. The lover and the beloved.

The innocent and the betrayed. Meaning

that to move out of the oppressor’s camp

is to forfeit innocence. Meaning

that to catch oneself at the point

of crossing a line is to wake in tears.

There is the fence. There is the wood.

There is the hunter by his billboard

for trespassers. Here is my face.

Scents of trails criss-cross the undergrowth

dense as twigs. A bird’s hopping is enough

to turn tail for, only to come out at night

sniffing the air clean, criss-crossed by moons

and witches’ brooms and cries of women

pricking the wood’s seven layers of skin:

drops of berries beading a trail

of witness, where the enemy has been.

THE WOMAN IN THE WALL

Why they walled her up seems academic.

They have their reasons. She was a woman

with a nursing child. Walled she was

and dying. But even when they surmised

there was nothing of her left but dust and ghost,

at dawn, at dusk, at intervals

the breast recalled, wilful as the awe

that would govern village lives, her milk flowed.

And her child suckled at the wall, drew

the sweetness from the stone and grew

till the cracks knew only wind and weeds

and she was weaned. Centuries ago.

AMANUENSIS

Mirza, scribe me a circle beneath

the grid that drew Columbus

from isle to isle, tipped the scale,

measured a plus and minus

in our round lives. Amanuensis,

do you hear me? Look at the tree

holding the sky in its arms, the earth

in its bowels. Oh, draw me

the rings in its bark, a beaded spiral

where I may walk on Persian

carpets woven in dyes from sandbanks

where goats graze and the melon

cools in the stream. Have you seen the dome

of the mosque? Our signatures are there,

among galaxies, infinities: an incredulity

that leads even infidels to prayer!

The pool in the square is green with twine.

The tiles in the arch are floods

of blue brocade. And those painted stars

in the vault, this hive of hoods

and white arcades, are the stars and the sky

I saw on a night in Spain:

coves of milk and stalactites; the very same.

So leave your sacks of grain

my Mirza, your ledgers and your abacus. Turn back

to brighter skills than these:

your mirrors and mosaics. From each trapezium,

polygon, each small isosceles

face, extract me, entwine me. Be my double

helix! My polestar! My asterisks!

Nestle in my silences. But spell me out

and rhyme me in your lunes and arabesques!

STONE OF PATIENCE

‘In the old days’, she explained to a grandchild bred in England,

‘in the old days in Persia, it was the custom to have a stone,

a special stone you would choose from a rosebed, or a goat-patch,

a stone of your own to talk to, tell your troubles to,

a stone we called, as they now call me, a stone of patience.’

No therapists then to field a question with another,

but stones from dust where ladies’ fingers, cucumbers

curled in sun. Were the ones they used for gherkins

babies that would have grown, like piano tunes had we known

the bass beyond the first few bars? Or miniatures?

Some things I’m content to guess: colour in a crocus tip,

is it gold or mauve? A girl or a boy… Patience

was so simple then: waiting for the clematis to open,

to purple on a wall; the bud to shoot out stamens,

the jet of milk to leave its rim like honey

on the bee’s fur. But patience when the cave is sealed,

a boulder at the door, is riled by the scent of hyacinth

in the blue behind the stone: the willow by the pool

where once she sat to trim a beard with kitchen scissors,

to tilt her hat at smiles, at sleep, at congratulations.

And a woman, faced with a lover grabbing for his shoes

when women friends would have put themselves in hers,

no longer knows what’s virtuous. Will anger shift

the boulder, buy her freedom, and the earth’s? Or patience,

like the earth’s, be abused? Even nonchalance

can lead to courage, to conception: a voice that says

oh come on darling, it’ll be all right, oh do let’s.

How many children were born from words such as these?

I know my own were; now learning to repeat them, to outgrow

a mother’s awe of consequences her body bears.

So now that midsummer, changing shape, has brought in

another season, the grape becoming raisin, hinting

in a nip at the sweetness of a clutch, one fast upon another;

now that the breeze is raising sighs from sheets

as she tries to learn again, this time for herself,

to fling caution to the winds like colour in a woman’s skirt

or to borrow patience from the stones in her own backyard

where fruit still hangs on someone else’s branch… don’t ask her

whose? as if it mattered. Say: they won’t mind

as you reach for a leaf, for the branch, and pull it down.

FAMILY FOOTNOTES

My arms in the sink, I half-listen

as someone keeps me company:

She’s such a sweetiepie, isn’t she?

I pause and to my own surprise

realize, seeing her suddenly through the eyes

of guests, how small she seems;

like a robin redbreast perched with other

mothers I thank god aren’t mine.

My father cracks a joke on the transatlantic

line, misreading my alliances;

decades of regret still failing

to make her an easy butt.

But his laugh is warm bubble, a devil

to slip into, like the fold of his cheek

and the film of his eye, film that I know

my own before long will look through.

My children are with me, as always, my son

even now sleeping under covers

I have no more to do with. He is always

loving. To say this, to think this

seems suspect in a world such as ours.

How have we escaped it?

My daughter is about to bumble in the door,

late as usual, and be sweet to me,

nattering on as I clatter in the kitchen,

her breasts within an inch of my arm.

Nothing seems to rattle her: embarrassments

that floor me, still, at my age.

She is chock-a-block with courage;

fresh air on her cheeks like warpaint.

Pooled in this – this love – and this – and this –

what has riddled me to long for more?

SHANKLIN CHINE

They lit lanterns down the Chine

in the summer season, or on Hallowe’en,

down winding steps through liverworts

and horsetails, past narrow banks

of watercress and up the final slope

that ended so abruptly at the gate.

It surfaces at moments, unlooked-for,

when the little crooked child appears

to bar your way: demanding no crooked

sixpence as she stands behind the stile

in her little gingham frock and the blood

she has in mind drawn behind her gaze.

Are you the Guardian of the Chine?

(Perhaps she needs some recognition.)

Of course she never talks.

She only has the one face: dark and solemn;

the one stance: blackboard-set;

and a wit as nimble as the Chine

stopping short at forgiveness

that could only come with time or power

or a body large enough to fit her brain.

Is there something I could give her?

Some blow to crack her ice?

Some human warmth to make her feel the same?

Genie of the Chine, she reappears at moments

when I am closest to waterways, underworlds,

little crooked streams through hemlock

and dandelion that end so prematurely –

though she is there, like Peter Pan,

or the barbed-wire children who bang tin cans,

or the child you would have loved,

like any mother, any father, had you been

an adult, not the child with no demands

for sixpences in puddings, pumpkins

on the table, or any pumpkin pies

gracing homes that had you standing at their gates.

Genie of the Chine, she reappears

from time to time, when I am closest to myself.

SICK BOY

In the shallow, like a dog, between the sideboard

and the sound of breaking water,

his fear curls.

From the high road by the stove

whose smoke is scenting speed

outside his travel –

Swish! A figure stooping

in the corner rinses fruit

beyond the peel,

places three magic colours,

dots, a water-wand to name them

by a bowl of tangerines.

Under the covers it locks him in:

the rod, the rail, the storm.

Oh Mum. The sea.

Sand trails off the shells,

feet going down, the brambles’

pale green store.

BLUE MOON

Sitting on a windowsill, swinging

her heels against the wall as the gymslips

circled round and Elvis sang Blue Moon,

she never thought one day to see her daughter,

barelegged, sitting crosslegged on saddlebags

that served as sofas, pulling on an ankle

as she nodded sagely, smiling, not denying:

you’ll never catch me dancing to the same old tunes;

while her brother, strewed along a futon,

grappled with his Sinclair, setting up

a programme we had asked him to. Tomorrow

he would teach us how to use it, but for now

he lay intent, pale, withdrawn, peripheral

in its cold white glare as we went up to our rooms:

rooms we once exchanged, like trust, or guilt,

each knowing hers would serve the other better

while the other’s, at least for now, would do.

The house is going on the market soon.

My son needs higher ceilings; and my daughter

sky for her own Blue Moon. You can’t blame her.

No woman wants to dance in her Mum’s old room.

CONFUSING ARRIVALS WITH DEPARTURES

Small and scuffed behind the sheet-glass pane,

I plant my feet, my shoes worn thin the way

I wear them thin, below the presences in aeroplanes

for whom I am not

the presence I would wish to be

ineradicable

as the naked girl who has walked through glass,

punched the shape of what-I-was to a pentacle in shards

and walked away

(unaware how waterfalls of blood must look

– from cheek to chest and so on down – to someone by a pool

who reluctantly removes their shades).

★

I wish to plant my name

on lips that circle in the airspace

of my loss; have them mouth me,

mutter ‘Mimi, all those houses, is she down there looking up?

Going about her business as the landing-strip approaches?

Watching me cross tarmac with baggage from the clouds?’

I scrape the ever-widening bowl for succour, for sweetness,

as all I stand to lose spins centrifugal,

only to find that sweetness part of what I stand to lose

while I so strong,

so centripetal,

grow from strength to strength.

★

I am a safety-pin

on the end

of the elastic distances of aeroplanes.

I spread my arms to the land’s thin rim

only to find a wireless sky and lines like

‘and will my fingers never smell of sex again?’

Someone taps me on the shoulder.

It is not the lover I would wish for.

It is a man who flies in aeroplanes;

spreads his papers in his lap;

looks down on earth’s receding map and mutters:

‘Over… Over… Over…’

IN SEARCH OF MELODRAMA

Where is the pain they only saw

when drunk as a lord she howled

obscenities? Even death,

the mourners hinted, eyeing

detachment on diagonals in space,

demands more decorum than this.

Why all the melodrama – her lover

used to say as though it were a form

of female illiteracy, plugging his own

speech with war and blood and scars –

can’t we just talk this thing through?

Is that what she does then, as she sips

asparagus soup with friends who saw her

grief stripped bare in the wolfdog fangs

the devil laughs in? Talks it through

in her head with the room where for years

he sat half-teasing, elegant knee draped

over elegant knee, the freckles on his hands

tap-tap-tapping a long, slow message

forming in the hangman’s game a name?

Where before the game was finished

the message came, cut short the thought

that had kept her going: you’ll see,

he’ll come to his senses in the end.

Is it there then, in her monologue pitching

into silence, queered by a presence who has

learnt to acquiesce? She’s not about

to take yes for an answer, she will whip him

back to life, make him tell it like it was:

No, my love, no! Time and time again.

THE POULTERER

His card shows nothing sinister. He stands

against a background sky, a farmyard scene:

against the duck-egg blue and fawn, his hands

are pale as vellum, sleeved in acorn-green.

His name, though scrolled in black like other names

from higher decks – The Hanged Man, Hierophant,

rich in papal gold, The Tower in flames –

his name, though less arcane, is more extant.

He deals in lower echelons than they:

in women, mad in chains, who hoot like owls;

in men who line the fence like ghosts in grey;

in little girls who dream of ginger cowls:

of claws that pierce the railings of their beds

where father stands; who dream in coxcomb reds.

‘YOU MUST LEARN TO MURDER YOUR DARLINGS’

And we did, we did.

Hid them under tree and bush.

Now I run. And wake.

Remember how he never called

me darling, never even wrote

my name in full.

And how I, too,

stopped spelling out sweet nothings.

How I kept my cool.

Beat him to the red.

Lopped these little limbs

and threw them to the wolves.

A ‘POST-FEMINIST’ DAWN

There are dawns of stone and pit: dead ends

whichever way you turn. A lover’s note. Friends

who run in grooves our mouths should have sucked,

rooting for the teat of depressions they have licked,

hungry for the milk, the empathy to spurt from it.

We who live in limbo

fungus, fern and fallacy

We who lie in utero

waste-products of phallocracy

We who dream of dawns

submit: crazed with the flog of directives

crumpling our anger like cupid’s missives

under pillows to corrupt our dreams, to make us

doubt the dawns our sisters wake to, out of focus

on a shore we cannot swim to in our reluctance to admit

the dream, the light, the ocean

how much has failed to fit

the picture painted for us children

the picture as We painted it

We who were framed.

And I ask myself, I ask you, is this it? All

that we were raised for, groped for, from the first bawl

at our mother’s thigh, to the last clambering in?

No, there is more, you would answer, thinking in

terms you would hate me to think of as making it.

What are We to make of it?

We who are womb and foetus

We who see both sides of it?

Must we swing, celibate, in the hiatus

of the dusk, till mother calls us in?

Or, loving women, have a better time of it? Invulnerable,

penetrable, in an age that breeds without us, the reversal

of what it means to have power or be powerless, to have blood

without a wound, to have seed with a consequence, to have food

for mouths not our own; even now, in the thick of it

fixed by those who frame us,

spayed by a fear stronger

than the urge to love and to fail us

canker We are not; and larger

than the dawn’s small stash of it.

THE WAITING HOUSE

‘Tem Eyos Ki went to the waiting house to pass her sacred time in a sacred place, sitting on moss and giving her inner blood to the Earth Mother… she smiled, and sang… of a place so wondrous the minds of people could not even begin to imagine it… But sometimes a woman will think she hears a song, or thinks she remembers beautiful words, and she will weep a little for the beauty she almost knew. Sometimes she will dream of a place that is not like this one.’

– Anne Cameron, Daughters of Copper Woman

And I will bring you sweetmeats of stars

and four leaf clover

and plait your hair in grassknot braid

that maidens weave

on holy days when streets are strewn

with widows’ weeds;

and I will rub your spine with persian essence

rose and thyme

and stroke the down that tingling purrs of home.

And you will sing me songs my mother

used to sing

of pomegranates’ stubborn juice sluiced

off silver trays

and rounded limbs in old hammams; and tales

of Taghi

at the kitchen-gate, gaunt and thin, slung

like a tinker’s mule

with children’s billycans, the smell of onion

taunting him.

And you will numb my rootless moan in murmurings,

bird of my breastbone

quieten, its sobbing still, its flailing wings;

and we will sit

in the waiting house, latticed by the sea,

in purdah drawn

by our sheet of hair, your cheekbone’s arc

half-lit;

and we will croon and whisper till the hardening

yellow dawn

strikes on the mud where crabs peer out to pan

like periscopes;

then laying down on curling moss our ghosting

shadows’ twine

in sieve of nature’s palm, you will give me

your dreams

and I will give you mine and dreaming still

your blood

will live, as mine in yours, in mine.

JASMINE

If you find

the end of the root

in the scent of jasmine

and bind it through

till your sight

is amnesia

and your breath

love’s wound,

you will wake with blossoms

starring your hair,

the will

to live more sweetly

girdling you

in ebbing rings,

like Titania

smiling at an ass.

ROOMING

This window holds the Aegean

on white-washed brick

I painted on a piece of garden

where I used to look for robins;

this the terrace,

smooth and silent,

an open arch that disappoints me.

Under a white mulberry tree

Persian polo players

are spraying cries of flit

on photos of my family.

I hardly recognise

wood, ringed with

melons, vowels, limes

or the Coronation Coach

on screens of thick dun paper

where my children swim; or best of all,

the nice brown egg I did.

How real the speckles look!

Long and many windows

my lover is around to cut out.

This my lizard patch

peppered in the dust

of poppies and nasturtiums

you can tell is much too small.

I can smell the sea,

her bed at night,

ink horses on the curtains.

The fridge is humming empty pinks

or green of sweet william,

throwing nightstocks on fingerprints,

some of whom are dead.

Cross-legged, the word-processor

– a Malaysian boy-dancer –

sits: gold and intricate.

With her saffron in the rice,

only the widow on the wharf

and I now know

any book I wish in seconds,

half-open to the sky,

may rain down bruises

– marrowflowers – on my thigh.

NO MATTER

No matter how green the fields,

how wide the moors,

how steep the silence as they lean

against my door;

no matter how openings fill

with birdsong, spring as pale

in golden arms as a feint

along my wall.

No matter that air smells of air,

that time leads nowhere like the brook;

that pen and paper sleep beside

a willow cup, an open book.

No matter that the empty chair

where first I saw you sit

sits still angled to our ghosts;

no matter that my mind can lord it,

have it fill again, your open

shirt still open to the greed

that would steal a hand inside its store.

No matter where my fingers lead me,

I am lost without their cause.

I see, I hear, I taste and smell

but failing touch – your touch, my love –

my sensing makes no sense at all.

IN LIEU OF A POSTCARD

What is it that your absences have nursed

in me? What ‘quiet grove’? What ‘dreamy view’?

No odyssey perfects those scenes of you

I ramble in, rehearsed and re-rehearsed.

No information bureau better-versed

in catalogue, no lace whose cutwork grew

in shocks of spider-margarita dew *

can map my moods’ terrain, her pocks of thirst.

And only habit, yours. I wonder if,

late at night, the cricket over, a criss-

cross rain outside is drumming while you snooze;

and wake to closing scores to find its riff

reminds you, not of deadlines you may miss,

but songlines more insistent than the blues’.

* Spider-margarita: a traditional pattern in Cypriot lace

REFLECTIONS

i

In the autumn garden

all the bedding plants are brown.

One might have guessed

how it would be, how it is,

the ‘clockflower’ vine

that is at its best

when the gardener’s blinds are down!

ii

Even as I miss you now I know

that were you with me even now

to share my hours,

the hours I would miss far more than ours

would be my own!

iii

Since, when I am near you

you croak, old lizard,

in silt and reed,

let a river pass between us;

a footbridge spring by lotus-

flower, orchid hang from bark,

bark of willow.

On the far bank,

let a soft grey form

be conjured…

Through mire and film,

wonder

to think she is your mate

and your sigh like a golden lantern

carry

across water…

iv

The light of the thief who steals by night

outshines the moon!

But where is the thief who steals his light

from love’s dark eyes? Out of sight,

stealing inside the glow of trust

she spills in every room!

LA BELLE DAME

Why brood on willow water? Surely hope

is something more than rope to hang a mood

on willow. Hang garlands on the stair! Come.

(Wainscot mice will steal a swatch that dwarfs them

in their lair, quick as any water rat

to spot the knot or head of pin to show

with monumental wit what good design

can do with trophies from the tide…) Come in.

I’ll sweep the hearth; you make yourself at home.

Let’s close the shutters: we’ll mull things over

and leave pale knights to loiter where they will

(moon along the banks where dreams of virgins

hold them in thrall to their own misgivings…)

We’ll call the squirrels in: let’s have a ball.

Here’s my store I’ll share with you: an apple,

a loaf I baked myself, a nut or two.

Dusk will soon be gone and tonight we’ll see

how big the moon is. Come here by the fire.

Let me smell your hair. Weeds are hanging there,

I’ll pick them out. Next time, you’ll know better

than to brood. Those banks of sedge and sorrel

never did do any good… water’s filthy…

Come on, there’s a good girl. Keep your head down.

(Look! I told you! Here they come, scurrying.)

A THANK-YOU LETTER

How lucid every arc, every plane, every mote

on lacquer’s ebony. The ivory keys are quiet.

Space reflects me in its symmetry. A light.

A wall. A shadow. And I alone in it.

Here a cushion. There a rug. A picture

hangs, the name of her who gave it; the names

of all these people, those who chose it or wove it,

reflecting facets I have lived, earning the gift.

Here is Mahmoud dead and gone, Simin lost

in the backrooms of Tehran and what happened

to the girl who wove kelims? She named her daughter

after me, sowing me in someone I may never see.

How loved I have been. Come and see my room.

The stems beneath the surfaces are as fine

as old calligraphy, but feel how carefully I laundered,

smoothed, placed in perfect harmony the names

of those who loved me, like portraits in a shrine

of all who have died in a family. As I near the alcove

someone has reserved for me in the iconography of memory

for my children to turn to from the horrors of their day,

I am grateful for the gentleness of losing

flesh-and-bloodness in gifts I will leave like gravestones

or, less grave, in songs that will age into elegies

if I choose to play some music, to remain oblivious.

P.S. I remember now the name of the girl

who wove kelims: Mundegar.

It means: she who remains.

TURNING THE PAGE

‘The mighty mountain-sentinel Demavand… becomes so familiar and cherished a figure in the daily landscape, that on leaving Teheran and losing sight thereof the traveller is conscious of a very perceptible void.’

– George Nathaniel Curzon, Persia and the Persian Question (1892)

This grey

is made more bearable

by the thought of sun

on your own brown skin

just over the horizon

and this loneliness,

looking over its shoulder

at its own old absence,

looks forward too

to a merry death

and the lucky West Indian

in a language that can be,

when all’s said, at least read

by oppressors, hopes

to honour his grandmother;

but what if every time

the thought was struck dead

as the tree where you kissed

in the mule-shade

of a glade in Damavand?

What if the city

that gave credence to your sickness

were as vanished as the home

you took for granted you would bless

with success and happy children:

were now as alien as the dun

of another tongue, of freckled skin?

Would you turn to the dying –

take a leaf from their book?

To history, Russia for example?

How dead would a page be

without the smile you drew

(in brackets) on the face

of a sun, of a country

on the other side?

EVERGREEN

And I have lived with green in playing-fields,

neighbours’ gardens seeping poison

through the fence: ground-elder flaunting

height and health where colour should have been,

the colours of my childhood, needed more than ever

in a land that adopted me, that turns me grey;

while the dress my mother danced in, golden

polka-dots and flounces, circles on its own,

sad as olde-time vaudeville, and camel, camel-

lilac of the slopes where shepherds’ lives

meet poppy every day, has settled on the leaves

of war, and every leaf has turned.

Even blues are not the same: of tiles,

of domes, of skies too dazed for blue;

or of shadows, mulberry-blue, in the room

you enter blinded, learning how to see again

gloom becoming someone dear, a grandmother

who gives you grapes she has quietly washed.

And white, like all the colours of the world

raising home, hazy as the verandahs

you half-remember, is something to avoid

in a land where no one’s hands are clean;

where dust is never sand but more a mirage

no one even yearns for, intent on lawns.

THE BOWL

‘The path begins to climb the hills that confine the lake-basin. The ascent is steep and joyless; but it is as nothing compared with the descent on the other side, which is long, precipitous, and inconceivably nasty. This is the famous Kotal-i-Pir-i-Zan, or Pass of the Old Woman.

Some writers have wondered at the origin of the name. I feel no such surprise… For, in Persia, if one aspired, by the aid of a local metaphor, to express anything that was peculiarly uninviting, timeworn, and repulsive, a Persian old woman would be the first and most forcible simile to suggest itself. I saw many hundreds of old women… in that country… and I crossed the Kotal-i-Pir-i-Zan, and I can honestly say that whatever derogatory or insulting remarks the most copious of vocabularies might be capable of expending upon the one, could be transferred, with equal justice, to the other.

…At the end of the valley the track… discloses a steep and hideous descent, known to fame, or infamy, as the Kotal-i-Dokhter, or Pass of the Maiden.

…As I descended the Daughter, and alternately compared and contrasted her features with those of the Old Woman, I fear that I irreverently paraphrased a well-known line,

O matre laeda filia laedior!’

– George Nathaniel Curzon, Persia and the Persian Question (1892)

i

The bowl is big and blue. A flash of leaf

along its rim is green, spring-green, lime

and herringbone. Across the glaze where fish swim,

across the loose-knit waves in hopscotch-black,

borders of fish-eye and cross-stitch, chestnut trees

throw shadows: candles, catafalques and barques

and lord knows what, what ghost of ancient seacraft,

what river-going name we give to shadows.

Inside the bowl, in clay and earth and limestone,

beneath the dust and loam, leaf forms lie

fossilized. They have come from mountain passes,

from orchards where no water runs or fields

with only threadbare shade for mares and mule foals.

They are named: cuneiform and ensiform,

spathulate and sagittate and their margins

are serrated, lapidary, lobed.

My book of botany is green: the gloss

of coachpaint, carriages, Babushka dolls,

the clouded genie jars of long ago.

Inside my bowl a womb of air revolves.

What tadpole of the stream, what holly-spine

of seahorse could be nosing at its shallows,

what honeycomb of sunlight, marbled-green

of malachite be cobbled in its hoop?

I squat, I stoop. My knees are either side

of bowl. My hands are eyes around its crescent.

The surface of its story feathers me.

My ears are all a-rumour. On a skyline

I cannot see a silhouette carves vase-shapes

into sky: baby, belly, breast, thigh;

an aeroplane I cannot hear has shark fins

and three black camels sleep in a blue, blue desert.

ii

My bowl has cauled my memories. My bowl

has buried me. Hoofprints where Ali’s horse

baulked at the glint of cutlasses have thrummed

against my eyelids. Caves where tribal women

stooped to place tin sconces, their tapers lit,

have scaffolded my skin. Limpet-pools

have scooped my gums, raising weals and the blue

of morning-glory furled around my limbs.

My bowl has smashed my boundaries: harebell

and hawthorn mingling in my thickened waist

of jasmine; catkin and chenar*, dwarf-oak

and hazel hanging over torrents, deltas,

my seasons’ arteries… Lahaf-Doozee!…

My retina is scarred with shadow-dances

and echoes run like hessian blinds across

my sleep; my ears are niches, prayer-rug arches.

Lahaf-Doozee! My backbone is an alley,

a pin-thin alley, cobblestoned

with hawkers’ cries, a saddlebag of ribs.

The Quilt Man comes. He squats, he stoops, he spreads

his flattened bale, unslings his bow of heartwood

and plucks the string: dang dang tok tok and cotton

rising, rising, is snared around his thread,

snaking, swells in a cobra-head of fleece.

My ancestors have plumped their quilts with homespun,

in running-stitch have saved a legend’s lining:

an infant in its hammock, safe in cloud,

who swung between the poles of quake and wall,

hung swaying to and fro: small and holy.

Lizards have kept their watch on lamplight: citrus-

peel in my mother’s hand becoming baskets.

My bowl beneath the tap is scoured with leaves.

iii

The white rooms of the house we glimpsed through pine,

quince and pomegranate are derelict.

Calendars of saint-days still cling to plaster,

drawing-pinned. Velvet-weavers, hammam-keepers

have rolled their weekdays in the rags, the closing

craft-bag of centuries. And worker bees

on hillsides, hiding in ceramic jars,

no longer yield the gold of robbers’ honey.

High on a ledge, a white angora goat bleats…

I, too, will take my bowl and leave these wheatfields

speckled with hollyhocks, blue campanulas,

the threshing-floors on roofs of sun-dried clay.

Over twigbridge, past camel-thorn and thistle

bristling with snake, through rock rib and ravine

I will lead my mule to the high ground, kneel

above the eyrie, spread my rug in shade.

Below me, as the sun goes down, marsh pools

will glimmer red. Sineh Sefid* will be gashed

with gold, will change from rose to blue, from blue

to grey. My bowl will hold the bowl of sky

and as twilight falls I will stand and fling

its caul and watch it land as lake: a ring

where rood and river meet in peacock-blue

and peacock-green and a hundred rills cascade.

And evening’s narrow pass will bring me down

to bowl, to sit at lakeside’s old reflections:

those granite spurs no longer hard and cold

but furred in the slipstream of a lone oarsman.

And from its lap a scent will rise like Mer*

from mother-love and waters; scent whose name

I owe to Talat, gold for grandmother:

Maryam, tuberose, for bowl, for daughter.

*Chenar: plane-tree

*Sineh Sefid: Mt White-Breast

*Mer: Egyptian goddess of mother-love and waters

A PERSIAN MINIATURE

(Shirin committing suicide over Khusraw’s coffin)

She told us: take a picture, an art postcard

– I took this Persian miniature – then take

the top right-hand corner and describe it.

Well… it looks like a face; two of the arches

that march across the background look like eyebrows

– not Persian eyebrows meeting in the middle –

but intersected by a nose, a pillar.

The nose has peeled and left a patch that looks

rather like a map of The British Isles.

The top left-hand corner she said to use

for the second verse – here I am on cue –

is also a face, only this one’s nose,

believe it or not, sports a large pink map

of America, or at least, the West Coast.

As if to banish doubts, a sea of stars

beneath it waves the flag. You see how hard

it is, how far away one gets from art,

and sixteenth-century Persian art at that.

Well, the third and final stanza – although

I can’t imagine how I’ll ever get it

all in one – is to take the two-inch square

at the bottom centre of the picture,

describe it, wrap it up and there you are,

you’ve got your poem. O.K. Three lines left:

Shirin and Khusraw (Romeo and Juliet)

are dying: he’s in agony but she,

though spraying blood on him, seems quite at peace.

So. That’s hardly the place to end a poem.

It’s interesting, though, to think: here is England

on the right, America on the left

and caught between the two, like earth itself

twin-cornered by the eyes of gods, Iran’s

most famous lovers lie, watched and dying.

How could a painter in Shiraz have known,

four hundred years ago, of this? Has time

rewritten him? Or was it always so?

Has power always called for sacrifice,

the dream of love on earth to trade itself

for paradise, the ‘Rose that never blows

so red as where some buried Caesar bled’?

And still the fountain flows from bowl to bowl,

from lips of stone to fields, from mines to graves;

and there, in Zahra’s Paradise for martyrs,

still bears the ‘Hyacinth the Garden wears

Dropt in her Lap from some once lovely Head’.

RUBAIYAT

for Telajune

Beyond the view of crossroads ringed with breath

her bed appears, the old-rose covers death

has smoothed and stilled; her fingers lie inert,

her nail file lies beside her in its sheath.

The morning’s work over, her final chore

was ‘breaking up the sugar’ just before

siesta, sitting cross-legged on the carpet,

her slippers lying neatly by the door.

The image of her room behind the pane,

though lost as the winding road shifts its plane,

returns on every straight, like signatures

we trace on glass, forget and find again.

I have inherited her tools: her anvil,

her axe, her old scrolled mat, but not her skill;

and who would choose to chip at sugar loaves

when sugar cubes are boxed beside the till?

The scent of lilacs from the road reminds me

of my own garden: a neighbouring tree

grows near the fence. At night its clusters loom

like lantern moons, pearly-white, unearthly.

I don’t mind that the lilac’s roots aren’t mine.

Its boughs are, and its blooms. It curves its spine

towards my soil and litters it with dying

stars: deadheads I gather up like jasmine.

My grandmother would rise and take my arm,

then sifting through the petals in her palm

would place in mine the whitest of them all:

‘Salaam, dokhtaré-mahé-man, salaam!’

‘Salaam, my daughter-lovely-as-the-moon!’

Would that the world could see me, Telajune,

through your eyes! Or that I could see a world

that takes such care to tend what fades so soon.

RICE

i

Ten years later, I recognise his profile in a Tehran cab.

You see these teeth, he said, leaning across the passengers,

what became of me?… I see him silhouetted in dazzle

as the tunnel ends on the last lap to Frankfurt, his hand

on the window’s metal lip, his cap in the other circling

like a bird then, loosed on the wind, beating a tattoo

against the wires as I watch him reach to the rack for his case,

send that too struggling through the window, socks and all.

I have come, he declared, to start at the start! Now, a decade

later, he asks: You see these teeth? He bares them in the light

to show how short, how straight they are. What became of me:

you wonder why? His fist emerges from his pocket, clenched.

I eat it all the time. My hand is never still, like a swallow

at its nest, going in, going out. Not a grain escapes.

He fingers his moustache. I even check in wing-mirrors.

See how it’s worn my teeth right down? His hand unfurls,

dabs at the back seat space between us. Please, have some.

What, raw? I ask. It’s rice, he urges. Rice.

ii

I have fled on mules, the star of Turkey in my sky, to start

at the start. I have come like sleet with Mary in the dark; swum

into hedgerows by the line. Gifts of weave and leather tucked

in polythene for friends, already fled or free, are dry.

Will they harbour us, we wonder, ten years, a revolution later,

towel us from swollen rivers chanting MARG BAR ÉMRIKÁ *?

iii

The cabs still carry passengers: my mother in her black chador,

my sisters among soldiers, now and then a face

blasted like a cake. They have granted me asylum. I write plays.

A friend I love in London has hung the Kurdish mules I brought her

on the same hook as an old sitar she never plays.

When she dusts them she thinks of me, and of rivers.

I told her of the man I met twice: once in a train,

once again in Tehran in those early days… what days they were!

Ah well. Her sister lives near Washington; the husband – Iranian –

works for the Department of Defence, and in real-estate; comes home

to scan The Post, its leaders on Japan: po-faced as she snatches

victory from jaws set ever closer as they wing towards Potomac.

* Death to America

HAIKU

On the verandah

the wet-nurse thinks of her own

pomegranate-tree.

EARLS COURT

I brush my teeth harder when the gum bleeds.

Arrive alone at parties, leaving early.

The tide comes in, dragging my stare

from pastures I could call my own.

Through the scratches on the record – Ah! Vieni, vieni! –

I concentrate on loving.

I use my key. No duplicate of this.

Arrive alone at parties, leaving early.

I brush my teeth harder when the gum bleeds.

Sing to the fern in the steam. Not even looking:

commuters buying oranges, Italian vegetables,

bucket flowers from shores I might have danced in, briefly.

I use my key: a lost belonging on the stair.

Sing to the fern in the steam. I wash my hair.

The tide goes out, goes out. The body’s wear and tear.

Commuters’ faces turn towards me: bucket flowers.

A man sits eyeing destinations on the train.

He wears Islamic stubble, expensive clothes, two rings.

He talks to himself in Farsi, loudly like a drunk.

Laughs aloud to think where life has brought him.

Eyeing destinations on the train – a lost belonging –

talks to himself with a laugh I could call my own.

Like a drunk I want to neighbour him; sit beside

his stubble’s scratch: turn his talking into chatting.

I want to tell him I have a ring like his,

only smaller. I want to see him use his key.

I want to hear the child who runs to him call

Baba! I want to hear him answer, turning

from his hanging coat: Beeya, Babajune, beeya!

Ah! Vieni, vieni!…

BABA MOSTAFA

He circles slowly and the walls of the room,

this Maryland cocoon, swirl as though the years

were not years but faces and he, at eighty,

in his warm woolly robe, were the last slow waltz.

‘Children’, he would say, ‘truly love me!

And I have always, always loved children.’

‘It’s true’, she’d say, coming through the arch.

‘Sarajune, you love Baba Mostafa, don’t you?

D’you love Baba Mostafa or Maman Gitty, hah?

Here, eat this.’ ‘For God’s sake, woman,

do you want her to choke! Come, Sarajune, dance…

da-dum, da-dum, da-dum, da-da…’

He circles slowly, the child on his shoulder

nestled like a violin and the ruches of a smile

on the corners of his lips as though the babygro’

beneath his hand were glissades of satin.

Wunderschön! Das ist wunderschön! He lingers

on the umlaut he learned as a student on a scholarship

from Reza Shah and on the lips of a Fräulein

whose embouchure lives on in him, takes him back

through all those years, through marriages, children,

reversals of fortune, remembering how in war-time

foodstuffs left his home for hers – manna from Isfahan,

sweetmeats from Yazd, dried fruit from Azarbaijan.

He circles slowly, on paisley whorls

that once were cypress-trees bowing to the wind,

as though these ‘perfect moslems’ were reflections

of his coat-tails lifting on a breeze from the floor.

‘I swear to God’ he blubbered, only days before

his laryngotomy, ‘I was a good man. I never stole.