8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Verve Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: A Jen Shaw Mystery

- Sprache: Englisch

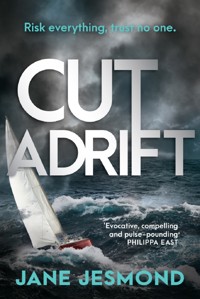

** SELECTED AS A TIMES BEST THRILLER BOOK OF 2023 & A SUNDAY TIMES BEST CRIME BOOK OF 2023 **

Risk everything, trust no one.

Jen Shaw is climbing in the mountains near Alajar, Spain. And it's nothing to do with the fact that an old acquaintance suggested that she meet him there...

But when things don't go as planned and her brother calls to voice concerns over the whereabouts of their mother, Morwenna, Jen finds herself travelling to a refugee camp on the south coast of Malta.

Free-spirited and unpredictable as ever, Morwenna is working with a small NGO, helping her Libyan friend, Nahla, seek asylum for her family. Jen is instantly out of her depth, surrounded by stories of unimaginable suffering and increasing tensions within the camp.

Within hours of Jen's arrival, Nahla is killed in suspicious circumstances, and Jen and Morwenna find themselves responsible for the safety of her daughters. But what if the safest option is to leave on a smuggler's boat?

The second instalment in the action-packed, 'pulse-pounding' Jen Shaw series, following Sunday Times Crime Book of the Month On the Edge.

'Riveting... Jesmond's first novel marked her out as an original voice in crime fiction, and the new book shows how the conventions of the genre can be used to reveal a personal tragedy' - Sunday Times (Best Crime Books of 2023)

'Jesmond's flawed characters add depth and complexity to a story that wears its sentiments on its sleeve, but is freighted with contemporary resonance' - Times (Best Thriller Books of 2023)

'In an over-saturated market, finding a new voice with something compelling to say in the crime writing field can be difficult. Thankfully there are people out there trying to deliver a twist on the genre, and Jane Jesmond is one of them' - On Yorkshire Magazine

'The thriller world has gained a compelling and seriously talented voice' - Hannah Mary McKinnon

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 493

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR THE JEN SHAW SERIES

‘An original mystery… A promising debut’ – Sunday Times on On The Edge (A Best Crime Novel of October 2021)

‘This amazing debut novel from Jane Jesmond will give you all the thrills you’ve been looking for and keep you gripped from the get-go… We feel as though we have walked into the dark and stormy moors where this story takes place’ – Female First

‘A surprising story filled with twists and turns’ – Living North

‘A gripping premise, a well-executed plot and an evocative Cornish setting’ – NB Magazine

‘The thriller world has gained a compelling and seriously talented voice’ – Hannah Mary McKinnon

‘Gritty, gripping, knotty, intense – this is going to be HUGE’ – Fiona Erskine, author of the Chemical Detective series

‘A beautifully atmospheric story that grips you from the start! Jesmond cleverly weaves a tale of intrigue and suspense – a talented new crime fiction writer. One to watch!’ – Louise Mumford, author of Sleepless

‘A high octane, no-holds-barred thriller. I couldn’t turn the pages fast enough!’ – Barbara Copperthwaite, author of The Girl in the Missing Poster

‘It literally had me on the edge from the word go. Tense, taut and thrilling’ – Lisa Hall, author of The Woman in the Woods

For Nikki

With all my love

Prologue

A Beach in Northern Libya

Rania pushed a corner of the rug hiding her aside so she could watch the streetlights flash past through the car window above her. Uncle Eso drove faster now they’d left the stretch of road between Tripoli and Sabratha behind and were heading to Zuwara. She’d pull it back over her head if Uncle slowed down.

Aya, her younger sister, curled up in the other footwell, whined a complaint and wriggled until their mother stretched round from the passenger seat to pat the little girl and tell her to hush.

Rania felt a moment of irritation. Aya should be used to travelling like this by now. They moved every week or so from one of Mama’s friends’ homes to another and every time they were crammed into a footwell or squashed in the boot. Anyway, Aya, at six years old, was half Rania’s size so she had nothing to complain about. Rania’s legs and body had suddenly elongated over the last few months and, although Uncle Eso had done his best, cutting away the underneath of the rear seat to make more room for them both, Rania was cramped and hot. Her legs ached from keeping still and her skin was scratchy with the ever-present sand on the rubber mat that crept into every fold of her body. She shifted. The comfort of a change of position was good even if it never lasted for long. Except now her phone, shoved in her pocket, dug into her narrow hips.

For a moment she considered pulling it out, then stopped herself. What would be the point? Her mother had removed the sim card the night everything changed. She couldn’t message her friends or play Fortnite or do anything except listen to the music she’d already downloaded.

Maybe she should do that. Because she could feel tears prickling behind her eyes as sharp as the sand that had worked its way up the cuffs of her blouse and into the crease of her elbow. When you couldn’t move or make a noise, crying was tricky. She hated it when her nose ran over her face and onto whichever part of her body she was lying on. Thinking about the night everything changed always made her cry but she couldn’t stop the memory unrolling.

She and Aya had been staying with her grandparents, while her parents were away on one of their trips. Mama had returned early and unexpectedly – and alone – with her arm in plaster and a look Rania had never seen before. Empty and distant, as though someone had peeled the skin off her face and stuck it on a robot.

Rania’s nose filled and her mouth trembled. She’d have to listen to music and let the beat clean everything out of her head. But Uncle Eso barked as soon as she twisted round to get her phone, so she had no choice but to lie there and remember.

‘We’re leaving,’ Mama had said, when Rania and Aya hurtled out of Jidda’s kitchen at the sound of her voice. ‘No! Don’t hug me. My arm is broken. Rania, go to your bedroom and take Aya. You must pack a few things together. Just clothes. Only as much as you can fit in your backpacks. And quickly.’

‘Nahla –’ Jidda protested.

‘Go, Rania.’

Something about Mama’s tone made her do exactly as she was told.

When she started back downstairs, Mama and Jidda were talking in urgent whispers in the kitchen. She stopped to listen.

‘Leave the girls here,’ Jidda was saying. ‘Your father and I will look after them. You know that.’

‘No. They must come with me.’

‘But their schooling, Nahla? Their friends?’

‘No. They’re not safe. They will be pawns in a game you don’t understand.’ Her mother’s frantic tone frightened Rania. Mama’s voice was normally soft and gentle even when her actual words were tough and uncompromising.

‘This will pass,’ her grandmother went on. ‘If you lie low, people will forget.’

‘They are not going to forget.’

‘I told you no good would come of messing with politics. But you would only listen to Ibrahim. See where it has brought you. You are a woman on her own. Rania is twelve and Aya is six. What kind of life are you taking them into? They will be safer with us. Your father is not without influence here in Tripoli.’

‘I say again, Umi, you don’t understand. They aren’t safe.’

Rania’s brain tried to make sense of what she’d heard.

‘Umi.’ Mama’s voice again. ‘I wish you’d leave too. You could still get out of Libya. Take a plane. I have friends who’d help you once you were away. Morwenna would welcome you and she knows many people who –’

‘Leave! You want us to leave our home? Your father’s job at the university? Our friends? You don’t know what you’re saying.’

‘Mama,’ Aya called from the top of the stairs. ‘Can I bring one doll? Rania said I couldn’t.’

Mama and Jidda came out of the kitchen and looked at them.

‘Why can’t you shut up for once?’ Rania hissed at Aya, then picked up her bag and walked down the rest of the stairs, trying not to wonder what Jidda had meant by Mama being a woman on her own.

Maybe she’d known then her father was dead. Or maybe the knowledge was forced into her mind over the following days, weeks and months, by the sheer weight of hints in Mama’s words, of her expression when Aya asked when Babba was coming, of his name murmured by the weeping hosts who greeted Mama each time the family moved, and by the way they stroked Rania’s face, with the bony nose and deep-set eyes she’d inherited from her father. She was certain Mama hadn’t told her Babba was dead. Surely she’d remember that? Except her memories of the last months were rocky and vague. She’d lost track of the order of events and without a timeline to tie them together they were loose in her head.

The one constant of these months was Aya’s endless chatter. There was no escape from it in the cramped rooms they hid in. It stressed Mama, who hated noise. It was one of her things. Even the jangle of Rania’s bracelets was too much. So Rania tried to keep Aya amused, to play her stupid games and tell her to hush every time she laughed too loudly. That was Rania’s overriding memory. That and the fear in those dark rooms with closed shutters pressing down on them like stones pressed white grubs into the earth.

Last night, it had changed. Someone had arrived unexpectedly, during the curfew, knocking quietly on the door of Uncle Eso’s apartment. Uncle Eso came and fetched Mama, and for a wild moment Rania thought it might be Babba. She tried to listen, easing the bedroom door ajar, but Aya, woken by her mother’s sudden departure from the bed they shared, had started to cry and Rania had to go and calm her. She heard her mother’s sharp wail of ‘No’, and afterwards the broken breaths of her weeping. They’d talked for hours and, in the morning, Uncle Eso told her they were going to Zuwara.

In the car, Rania let herself remember the holidays they’d spent at Zuwara. The sand, too soft for sandcastles but gentle beneath her toes. An endless strip of it, dotted by palm trees and beach huts selling pastries, sinking into the turquoise sea. She’d like to swim in the sea again and sit on the beach afterwards and sift the sand between her fingers and dream of her future. The sort of dreams she would never tell anyone. About when she would be a famous singer touring her first album of songs with the reviews calling her the spokesperson of her generation, a poet for everybody, like her mother. About the houses she would buy in far-flung places and stay in quietly until someone recognised her quite by chance in a local shop and she’d have to smile and say, yes, she was Rania Shebani.

Uncle Eso, in the seat in front of Rania, shifted suddenly and his weight pressed into Rania’s knees. The car swung right and raced across bumpy ground.

‘Road block,’ Uncle said. ‘I don’t think they saw us. We’re close now.’

They continued on little roads and the streetlights stopped appearing in the dark sky. Uncle rolled down the window and Rania heard the sound of the sea. The contrast between her recollections of Zuwara and their fear-filled mode of travel began to worry her.

Mama had said they were going to Zuwara to take a boat. Memories of golden days on the water had slipped into her mind but now she realised she should have asked Mama what she meant.

Not that Mama would have told her.

The thought took her by surprise. As did the feeling of resentment it provoked. She loved Mama but she couldn’t shake off the feeling she should share more with her. Actually Mama didn’t share anything with Rania, except the kind of soothing answers she gave Aya that meant nothing. It was all very well to be still waters running deep as Babba called Mama but… Babba. Oh, Babba.

She gave up the fight not to cry.

The car stopped and they eased themselves out. They were on a beach. It was night but they were not alone. Rania stared at the crowd sitting on the sand as Uncle took their bags out of the boot. Aya moaned about the dark and Mama, a stranger in the black abaya and niqab she’d worn for the journey, whispered to her. A couple of men detached themselves from the group and came up to Uncle, sticking their faces into his. Angry words Rania couldn’t hear passed between them and the men shook threatening fingers, but Uncle stood his ground. Afterwards he spoke to Mama.

‘They say I must go. But everything is fine. The boat will be here soon.’

‘The boat. Where is the boat?’ Aya’s voice cut through the silence. Faces turned to stare. There must, Rania thought, be a hundred pairs of eyes looking at them. Prickles of fear traced paths up and down her arms.

‘Nahla, you must keep the child quiet.’ Uncle’s voice was panicky.

He embraced them one by one. Whispering messages in their ears. He told Aya to stay silent. Rania knew because the little girl put her finger to her lips as he spoke. He asked Rania to look after her mother and her sister. ‘You are a big girl now, habibti. And I couldn’t be prouder of you if I was really your uncle. When I look at you, I see your father. Your mother needs you to be strong like he was. You understand?’

She nodded because she thought she did. It was true Uncle Eso wasn’t really a relative but if Rania had had an uncle she would have liked it to be him. As he strode away into the dark, she wanted to run after him. Back to the car, back to the footwell. She wanted to leave this beach of unnaturally still people behind. Go to Jidda’s. And to school. And her friends. But before she could move, Mama pushed her down to sit on the sand with all the others and the sound of Uncle’s car creeping over the stones and away told her she’d left it too late.

A stir among the men encircling the crouching and sitting people. In the distance, the noise of splashing. A few flashes of torchlight revealed a large inflatable boat coming towards them. It bucked and rolled on the choppy sea, so unlike the rippling blue-green waters of Rania’s memories.

The crowd stood as one. Rania realised they were all waiting for this boat. The boat for her family must be coming later. A proper boat like she remembered, with neat bunks that doubled as seats and a table that folded away, a little kitchen with a fridge where Babba kept his squirming bait despite Mama’s laughing complaints.

She looked up at Mama ready to ask, but Mama had stripped off her niqab. Her eyes and mouth gaped holes in her face.

‘Mama.’

‘Hush.’

Mama put Aya down, dragged the abaya off and picked up their bags, heading with the crowd into the water and pushing Aya before her.

‘Quick,’ she said to Rania.

A man seized the bags from her and threw them back on the sand, gesturing at Aya with what Rania realised was a gun. It was black and metallic, and she didn’t think it was a toy. Mama hesitated then picked up Aya and plunged into the water, leaving the bags behind.

Something split inside Rania as she ran after her, only vaguely aware of the tears running down her face. The beach shelved steeply and the water reached Rania’s waist quickly. Ahead of her, the first of the crowd were at the boat and hauling themselves aboard as it tilted from side to side under their weight. How would they all get on? There wasn’t enough room.

The sea was up to Rania’s neck by the time she got near. Her feet slipped away as she stretched up to grab the boat’s side but a man leant down and seized her, lifted her up and inside where the rocking knocked her off her feet. She crawled out of the way. Mama held Aya up to the same man but her sister, shocked into silence up to now, panicked and started to scream. The man swung his arm back, the movement casual then sharply forward until it connected with Aya’s head in a resounding slap and knocked her head sideways. Before the little girl could react, he slapped her again.

‘Be quiet,’ he said.

And she was.

Mama dragged herself in and the three of them squashed together. Mama gathered Aya to her, burying her in her body briefly then holding her away to examine her face. In the dark it was difficult to see the damage. Aya’s lip was cut and one eye was closed. The bruising would show later. But it was her other eye, unfocussed and wide, like the eyes of the butchers’ dead and bloody sheep’s heads at the Friday market near Jidda’s, and the complete stillness of her face that shocked Rania. She wrapped her arms around her sister, whispering comforting words and hoping Aya would answer in her too shrill voice so Rania could tell her gently to hush while she hugged her tighter and promised nothing bad would happen again. But Aya was limp and motionless in her arms as the boat set off.

At first Rania was sick. A lot. And glad to be near the side. Later, the second night, she thought, she was less happy there. The boat had softened, its edges no longer rigid, and waves broke over the top and swilled round her feet. She was afraid of tumbling out until exhaustion took over from fear and she slipped into a peaceful state, unaware of even the wilder splashes. She dreamed of her songs. Of Babba and Jidda. She chatted to her friends. She wandered as far into her head as she could, away from the growing panic around her as the boat sank deeper and deeper into the sea.

So, when the ship appeared in the distance, the shouts didn’t wake her. Nor did the orange lifejackets hurled down to them from above. It was only when Mama shook her and thrust her head and arms into the rough plastic vest that she came to and saw, towering above, the dark blue hull with white writing emblazoned on the side. Sea-Watch, she read. And then a little further along, Amsterdam. She knew Amsterdam from a jigsaw of Europe Jidda had. Amsterdam was in the Netherlands, with a picture of a girl in wooden shoes and a hat with curly horns.

‘Are we going to Amsterdam, Mama?’ she asked.

Mama didn’t answer but the woman in front turned.

‘Malta,’ she said. ‘I think we’re going to Malta. Here, take this.’ She passed Rania two of the silver blankets that were dropping from the boat above.

Rania didn’t think Malta was on Jidda’s jigsaw and Mama’s face, locked with numbness, revealed nothing. She wrapped a blanket round herself and one round Mama and Aya. Something her father said came back to her. You must always thank a stranger for their kindness, habibti. Otherwise they might choose not to help the next person who needs them. She waited for her mother to thank the woman and, when she didn’t, Rania smiled back.

‘Thank you,’ she said.

Aya clung to Mama like a limpet but she was quiet. Not that it mattered anymore because all around them there was noise. Sailors called from above and answers were shouted back.

‘We’re going to Malta,’ Rania told Aya, because no one else was going to. The little girl didn’t seem to hear her.

‘Mama,’ Rania repeated. ‘We’re going to Malta.’

But her mother seemed to be unaware of Rania’s existence. Her gaze was focussed on something far, far away.

An acid flame of anger flickered in Rania’s stomach.

PART ONE – Spain

One

I fled Cornwall in the quiet season. The overwintering curlews were still pincering the mud flats in the estuary for worms and shellfish with no thought of heading off to their breeding grounds in Scandinavia and Russia, while the skies were empty of swallows still sunning themselves in Africa. In a few weeks the changing seasons would drive the birds to migrate along the tried and trusted routes to their summer homes but I could wait no longer. My body twitched with unspent energy.

My hands, badly lacerated when someone tried to kill me at the end of last year, had healed and hours in the gym had restored me to peak fitness. I’d even been parkouring in Plymouth. Sensible parkouring with a club dedicated to ‘developing the strength and balance that would enable practitioners to interact with their environment safely’, to quote their website. This was code for Strictly no nutters allowed.

So I’d kept quiet about my history.

But now, it was time to go climbing again like I’d promised myself. Except not in Cornwall. It had witnessed too many of the crazy escapades I’d turned my back on. Plus I was staying at Tregonna, my childhood home, with my brother Kit and his wife and small daughter. I didn’t want Kit to know what I was doing or, worse, to offer to come along. This was between the rock and me.

So I went to Spain. It was cheap and warm. It had plenty of mountains and it was nearby. My choice had nothing to do with a postcard I’d been sent. A postcard of a bar with a cork ceiling in Alájar, a little village nestling in the lower slopes of the Sierra Morena. That was pure coincidence.

I picked up a battered campervan from a second-hand dealership in Malaga and headed northwest through flat fields of olive trees, grey-green and dusty under a milky-blue sky. The austere beauty of the high sierras called me and when the mountains appeared between gaps in the softer hills, my blood sang in my ears and I knew I’d done the right thing.

My days were spent on the rock. Climbing. Safely. All kit checked and backed up and I used a top rope or fixed anchors as I went, even if it meant a long hike at the beginning and end of each day. Not that I use the ropes to climb. They’re only there to save me if I fall. It’s called free climbing but there’s nothing free about it, really. You’re trussed up like a chicken ready for roasting.

The individual climbs have blurred into a single memory that’s purely physical: the roughness of the stone against my fingers and its coolness; its shape against the sky, curved here and jagged there; and my muscles tightening and loosening as I climbed. Over the days the itchiness seeped out of me and left calm behind.

Most evenings I was too tired to do more than snatch a meal at a local café and use their internet to decide where to go next. At night I parked the van on the side of roads that clung to the mountains so that when I opened the door in the morning the view rushed in to fill the space. It was as beautiful as I’d hoped it would be.

And in the quiet I thought about the recent past.

My love of climbing had been overwhelmed by the urge for thrill, for those magic moments when adrenalin sparkled through my veins and caressed my skin. I’d never felt so alive as I did then. However, other people had got hurt in my chase after excitement so I’d made myself give up climbing completely, until a mad race across the moors in Cornwall, fleeing for my life, had left me with no alternative but to escape by climbing. The other magic had returned then. Not the wild thrill of danger but the quieter happiness of moving in tune with the cliff face, the intertwining of fingers and limbs and body with the rock in a dance of equals. I’d known then I needed climbing back in my life. I’d sworn to climb alone, though. No one else would ever get hurt because of me. These days in the mountains in Spain had shown I could succeed. I realised I’d made my peace with the rock.

But as always when I remembered the night on the moors, Nick came into my thoughts. Nick Crawford, the undercover policeman, who’d escaped with me and disappeared straight afterwards, whisked away by his bosses and never heard from since.

Apart from the postcard he’d sent.

I hadn’t thought of him for days. No, that was a lie. He’d been in my head like the constant hum of traffic in London you learned to ignore. Unanswered questions, I told myself. You can’t get him out of your mind because he arrived in mysterious circumstances and left as suddenly and secretively. That’s all. But part of me knew I’d travelled hundreds of miles to Spain on the whisper of a promise. A shared moment on a dark hillside, full of possibilities, when Nick had said he’d drink to me in a bar with a ceiling carved from cork. Wet and exhausted from our flight across the moors, we’d said goodbye then and I’d watched him walk away to the waiting police car and disappear into the night.

I pulled the postcard out of my jeans pocket. It had reached me weeks later, when Gregory, my hometown’s retired lighthouse keeper who Nick had trusted, gave it to me although there was no address and no Jen Shaw written anywhere. Nor was it signed. It could have been from anyone to anyone but Gregory knew it was for me and I knew it was from Nick because the picture showed the inside of a typical Spanish bar. Nothing special except for the intricate and fabulous cork ceiling, carved like brown lace shaped into flowers. There might be a few bars in Alájar but there’d only be one with such a ceiling. Four words were written on the postcard. Wish you were here.

And when I first read the words, I knew I’d been waiting for this. That, in my heart of hearts, I hadn’t thought our goodbyes were forever. The postcard was an invitation but one that was whispered so no one else could hear.

And I hadn’t known what to do. I knew nothing about Nick really. It might be fun to find out, it might be exciting, but it might turn out to be a big mistake. So I’d waited.

But now it was time to decide. Alájar was only a day’s drive away and my return flight was fast approaching. I took a deep breath and tore the postcard in half. Nick Crawford – if that was his name – was probably trouble. I didn’t need any more trouble. Not now I’d conquered so many of my demons. He was best relegated to the pile of might-have-beens.

I was happy as I was.

The next day I climbed a great granite face overlooking a forested valley. The view was magnificent and distracting. I kept on stopping to gaze at the distant peaks crowned with late snow that poured dark green trees down their slopes, the flow only broken by spurs of rock like the one I was edging up. It was a straightforward climb. Dull, really. To my side I noticed another way up via a long thin fracture leading to an overhanging cliff, easily reached with a series of finger locks and foot smears, but getting over the jutting rock at the top of the overhang would be a serious move. I’d have to leap for the next hold. For a moment my body wouldn’t touch the rock and I’d fly through the air. The old sense of boredom curled an arm round me and whispered in my ear that it might be fun.

Except I was clipped into a top rope and it wouldn’t reach. I’d have to climb down, walk up the path at the side of the face and move it, then climb the tedious pitch again.

The urge faded.

Until my hands brushed the clasp of my harness and the image of them undoing it slipped into my brain.

I didn’t, although the effort of denial shocked me. It coated my skin with a film of sweat as I made myself chalk up and move on.

At the top I sat on the grass and stared out at the rows of mountains descending towards the coast to the south and Portugal to the west. The sun was still high in the sky and its warmth licked my skin. Eagles circled far above, as silent as was everything else. No buzz of insects. No goats’ bells jangled. I was too high for them.

I thought about what had just happened. I’d nearly blown it, nearly let the adrenalin junkie out of the bag I’d put her in after all the grief she’d caused last year. And, for the life of me, I couldn’t work out why it had happened now. Now that my life was as ordered as it could be.

And Nick came into my thoughts again, dragging with him the cloud of unanswered questions. Maybe I was unsettled because of that. Maybe I needed to find some answers.

I didn’t trust myself to climb any more so I headed south but, before I reached the main roads to Malaga and the airport, I turned west into gentler countryside where soft hills were lined with pastures of oak – cork oaks, stripped of their bark below head height, and bare holm oaks whose acorns carpeted the ground beneath where a few wild flowers braved the mists lying in the hollows. The acorns were for the pigs, I was told by the owner of a bar where I stopped for lunch. The pig was king here – coddled, acorn-fed money on legs – and he carved me a plate of their ham, deep red and shiny but so thin I could see the sharp outline of the village chapel through it.

I reached Alájar late that evening. A little village strung out along a river. Its name meant ‘stone’ in Arabic and a rocky cliff, pockmarked with caves, shot up from the forest at its edge. I parked the van on its outskirts and slept.

The owners of the small café I chose for breakfast spoke English well. They knew a lot about the tourist sites in Alájar but they didn’t know of any British people. Not ones who lived here. There were lots of British tourists, most of the year, although the summer months could be quiet. It was very hot then and people preferred the coast, but they hadn’t been here long themselves, only a couple of years, so they didn’t know everybody. They came from the city. From Malaga. And it took time to fit into a village like this. Did I realise? I nodded and said that I did.

After breakfast, I took the road that wound up the side of the cliff above Alájar and looked down at the village. It was the shape of a lizard basking in the sun. Not that the sun was shining. Today was wintry and damp. The white-painted houses with their red roofs nestled in a forest of bare-branched trees. I wondered again at the strangeness of Nick being here, in the middle of deepest, rural Andalusia, where properties outside the villages and towns rarely had mains electricity and people could remember the time before the roads were built. A flicker of doubt tainted my excitement.

In the centre of Alájar, the main bar overlooked a square lined with plane trees for shade in summer. No need for that this evening. It had drizzled all afternoon. Water still dripped from the branches and mist rolled down the hills towards us. A few hardy tourists sat outside. Walkers, I thought, judging from their waterproof trousers and thick boots. They had the smug look of people who’d hiked long miles during the day.

The bar was called El Corcho. It took me a while to realise this because the other signs that plastered its front, advertising Spanish beer and local fiestas, crowded out the simple writing above the door. It took even longer for my brain to work out Corcho might mean cork.

Inside, the ceiling was everything I’d expected and the bar was quiet. Too early for locals, I thought. The barman, a fearsome man with a shaved head, earrings and arms covered with tattoos as intricate as the bar’s ceiling, glanced up. His name was Angel according to the only other person sitting inside, an elderly man watching a football match on the TV.

‘Good evening.’ His English accent was good and his voice much gentler than his appearance. I realised he wasn’t much older than me.

‘Coffee, please. With milk.’

I steer clear of alcohol because I don’t like the places it takes me to.

‘Bad weather for walking.’ He gestured at the sky. ‘You are hiking?’

‘No. Climbing.’

His eyes stopped flicking round the bar and the tables outside and focussed on me.

‘On your own?’

‘Yes.’

I picked up my coffee and prepared to move away. The last thing I needed was someone hitting on me.

I chose a seat right at the front by the glass windows and began to wish I hadn’t come here. I’d give Nick a couple of hours. No more. If he didn’t turn up by then, I’d leave. And tomorrow I’d go home. Forget about him and his stupid postcard because he needed to play his part too. He’d sent an invitation and he should be here every night on the off chance I might accept.

Angel, now on the phone, gave me a quick, hard look as I sat and I glared back at him. He could get lost too. He turned his back on me.

Ten minutes later, the church bell rang nine o’clock, the lights outside the bar came on, reflecting in the puddles on the square, and the locals emerged. Old men shuffled out of their tall houses and farmers in muddy cars emerged from narrow, cobbled streets built with donkeys in mind. A trickle of professionals who must have jobs in the nearest city arrived, the men slick in designer jeans and sweaters and the women with their endlessly long legs clattering over the cobbles in vertiginous heels. They gathered outside the bar, kissed each other or shook hands, spilled into the road and forced the cars to swerve round them.

Something familiar about the back of a driver’s head, sticking out of a car window as he reversed into a narrow space in the square, jolted the pit of my stomach. I thought it was Nick and, when he got out of the car, I saw I was right. His dark curly hair was long and a coating of not-quite-beard darkened his jaw making him look untidier but more relaxed and open than when I last saw him.

I thought I liked it.

His car was similar to the battered thing he’d driven in Cornwall apart from the clutch of ornaments hanging from the rear-view mirror. Every Spanish car had them. Be careful, I warned myself. He was a chameleon, changing his colour and ways to fit in wherever he went. I thought I’d had a glimpse of the man underneath in Cornwall.

At least I hoped so.

He leaped the low wall separating the square from the road without looking and went straight to Angel at the bar. Their heads bent forward as they spoke and someone jostled my table. I turned away and reached out to grab my drink. When I looked back, Nick was already walking towards me through the crowd of people inside, his expression politely blank, which was annoying because now I’d never know what his first reaction on seeing me was. I’d never know if he’d hoped I’d be here.

He came over to my table and I felt the heat rise in my face as embarrassed thoughts raced through my mind.

He smiled. A smile with a hint of amusement. Like all the times he’d smiled before.

I smiled back.

‘Is this seat free?’ he asked, pulling the chair from the table.

I looked him up and down, taking in the stained jeans, the crumpled shirt sleeves, rolled up to show tanned forearms overlaid with dark hair, and the blunt fingers. A shadow of uncertainty flitted across his face when I didn’t reply. I was pleased about that.

‘Hello, Jenifry Shaw,’ he said. ‘And welcome to Alájar. What brings you here?’

Good question, I thought.

‘Curiosity,’ I said and nodded for him to sit. ‘Simple curiosity.’ And in case he hadn’t got my meaning. ‘Nothing except that.’

He bowed his head in an oddly formal manner.

‘Then I hope you’ll stay for a while. Let me show you around. It would be my pleasure and the least I can do. After all, you did save my life.’

Two

Nick did show me around. It was a whirlwind of sightseeing, every day crammed with visits to castles and churches and mosques. We went to museums, where I learned the region’s history, and down caves of weird crystal formations. We walked for miles along the walled dirt tracks, only wide enough for two donkeys to pass, that had connected the villages and towns for centuries, and through the oak and sweet chestnut woods lining the slopes Alájar nestled in. We wandered round the market in the nearest town buying enormous juicy olives and fingering the gaudy, joyous pottery.

One day we drove to Seville and visited the Alcázar Palace with its myriad of gardens and afterward ate sweet, crispy torta de aceite on the steps of the Spanish pavilion while we cheered students from the local flamenco school as they danced for the tourists.

Once we spent the evening sitting in the square at Alájar, watching the bats swoop in and out of the caves in the vast cliff towering over the village and listening to the animals in the forest.But mainly we went to the bar or one of the little restaurants, where everyone called Nick ‘Nico’ and chatted to him while I smiled and wished I’d paid more attention to Spanish lessons at school.

For all intents and purposes, I discovered, Nick was Spanish. His grandparents came from Alájar, along with their parents and their parents’ parents. His family, the Carrascos, had roots in the area that had been unbroken for centuries until Nick’s mother, an only child, married a Scot and left. However, Nick had spent every holiday in this remote corner of Andalusia as well as his last two years of school. And his grandparents had left him their house when they died. He was related to a great number of people here; Angel from the bar turned out to be a second cousin.

He was a wonderful companion, knowledgeable and amusing, brimming with little stories about his childhood and the places we visited and the people we met. However, after a week or so, I began to wonder if he was playing yet another role – the perfect and charming host enjoying himself as he showed a friend around his beloved home. Not that I’d been to his actual home. He picked me up and dropped me back at my campervan, parked now in an old farm where a group of hippies lived off-grid. There was water from an old well and enough electricity from their windmill to keep my phone and laptop charged. Hot showers were out unless I went down the hillside and used the ones in the bar.

Some subjects, I realised, were forbidden. He never talked about his work. Nor his family in Scotland. I didn’t even know if his real name was Crawford – I suspected not. He was known locally as Señor Carrasco, his grandparents’ name.

‘Do you feel Spanish or English?’ I asked him one afternoon as we were driving back from the market at Aracena. Today the skies were clear and piano music filled the car. It was one of the few things I’d discovered about Nick. He loved music and it accompanied him everywhere. Sometimes it was classical; sometimes ballads and rock anthems from the past fifty years. He adored the music of Andalusia but also had a strange liking for punk music from the late seventies and early eighties.

‘Don’t you mean Spanish or Scottish?’ he replied.

‘You don’t have a Scottish accent.’

‘I can.’

‘Yes, but you don’t.’

‘Not when I’m talking to you. But I do when I talk to my… to Scots.’

I half thought he’d been going to say his family but before I could ask him about them, he began an amusing anecdote about an elderly farmer who’d lived in Linares de la Sierra, the little village of white houses we were passing, and how he’d lost his pigs in a storm.

I laughed when Nick finished but my heart wasn’t in it. I was sure he’d diverted me from asking about his family. It wasn’t the first time either.

I cast a look at his face but it was a blank and his eyes were fixed on the road ahead. His hands moved smoothly over the steering wheel, gripping and relaxing as he guided the car round the twists of this serpentine road.

Shit! Why did I find him so attractive? There was no point denying I did. No point denying that I wanted him to be more than a charming tour guide. That my body felt his nearness like it felt the heat of sun-warmed granite without touching it. I wondered how his skin would feel against mine. Would its touch ripple a shock along my nerves? Would it be warm and smooth over muscle and bone? Would it…

‘How’s Morwenna?’ he asked suddenly and when I didn’t reply straightaway, added, ‘Your mother, I mean.’

I took my eyes off his hands and saw he was looking at me. Suddenly breathless and wondering if I was blushing, I gathered my thoughts together fast, glad he couldn’t read them.

‘She’s fine.’

‘Good.’ He cast me another look. ‘I like your mother. She reminds me of one of my aunts.’

An aunt, I thought. She might not be his immediate family but it was the closest he’d come to talking about them. I opened my mouth to ask about her but he got in first.

‘What’s Morwenna up to?’

‘I wish I knew.’

‘You don’t?’ He laughed. ‘How very typical!’

‘What, of me or of her?’

‘Both of you.’

‘My mother’s crazy. You know that.’

‘And you’re not?’

‘No. Well, I’m not crazy like her. Anyway I don’t know what she’s up to. She’s gone off and we don’t know where.’

‘She’s left Tregonna?’

Nick sounded startled and I wasn’t surprised. Tregonna was Ma’s beloved family home in Cornwall and her refuge against a world she claimed had lost its way. It was hard to imagine her leaving but it had come at the end of a long and stressful time, culminating in a terrible row with Kit when he’d discovered our father still owned Tregonna although Ma and Pa had split up years ago. After the row, Ma had stormed out and not come back.

‘Kit’s trying to find her,’ I said. ‘He needs her to sign a few things but we’ve heard nothing from her except a postcard.’

‘Nothing but a postcard?’

His surprise annoyed me. Or maybe it was talking about Ma that irritated me.

‘Yes, a postcard. People in my life seem to think it’s an acceptable way to communicate.’

He didn’t react. He seemed lost in his thoughts. I wished I knew what they were but he was so difficult to read.

‘Gregory might know where she is,’ he said, breaking the silence that had crept between us. ‘I bet she’s been in touch with him.’

Why hadn’t we thought of that? Ma was very close to Gregory, the ancient and retired lighthouse keeper who’d given me Nick’s postcard. He lived down the road from Tregonna in a tiny cottage at the base of our local lighthouse. She’d have been unlikely to go off without a word to him although she might do that to her children.

‘How is Gregory anyway?’ Nick asked.

‘The same really. Social services tried to persuade him to go into sheltered housing in St Austell recently but he refused. He’d be lost away from the lighthouse. It reminds him who he is.’

The lighthouse might be an anchor for his identity but I wasn’t sure Gregory knew when he was any more. He confused the present and the past although he lived in both with equal determination. A couple of times he’d mistaken me for Ma, and Kit said he often called him Charlie, our father’s name.

‘I hope your brother’s keeping an eye on him.’

Nick had liked Gregory, I remembered, and even more strangely, Gregory had liked Nick.

‘Everybody is,’ I said shortly, knowing Nick’s concern hadn’t stretched to keeping in touch with Gregory himself.

Forming fleeting relationships then disappearing was part of his job. He must be used to it. Maybe too used to it. Too used to playing a part and too used to keeping his barriers in place. For the millionth time, I wondered what I was doing here.

‘I’ll be flying home soon,’ I said.

I hadn’t meant to say it but as soon as I did, I knew it was the right thing. I needed to know whether or not Nick wanted me to stay. Nothing more.

He was silent for a long few minutes during which I felt stupidly sad and confused, then he pulled into a small lane off the main road and turned the car round.

‘What are you doing?’

‘If you’re going back soon, there’s one thing we haven’t done and tonight’s the perfect night. We’re going up into the mountains. Are you ready for an adventure?’

He smiled at me with eyes that held a thousand questions and my heartbeat quickened in response.

‘No,’ I said and straight afterwards I wasn’t sure if the No was for him or for the flicker of excitement inside me. ‘I don’t do adventure anymore,’ I added.

‘Seriously?’

‘Yup.’

His smile faded.

‘What’s happened? The Jenifry Shaw I met in Cornwall, she was up for anything.’

‘Well, this one isn’t. She’s learned her lesson. She doesn’t do adventure.’

‘That’s a pity.’

‘I thought you didn’t like climbing anyway,’ I said. ‘You told me you hated heights.’

He laughed. ‘I should have guessed mountains and adventure meant climbing to you. I want to take you stargazing. Not climbing. And not dangerous.’

‘Stargazing?’

‘Yes. It’s going to be a clear night and the mountains above us, the Sierra Morena, are part of one of the largest natural starlight reserves in Europe. There’s no light pollution so the skies are beautiful. You must have noticed when you were climbing up there.’

I hadn’t. But then I’d been tired in the evenings and preoccupied with planning the next day’s climb. I’d never thought to look up because you can’t see the rock in the dark.

Stargazing. Why not?

‘OK,’ I said. ‘Let’s go.’

He drove up into the mountains and into the fading light with music crooning in the background. Neither of us spoke as the setting sun flamed orange and sank behind the sharp black silhouettes of mountain ridges, and night surrounded us. We stopped by a little cabin in the middle of nowhere and got out of the car.

‘Don’t look up,’ Nick said as he turned on a torch. ‘I want you to see the stars when there’s absolutely no light.’ He rolled a rock over and picked up a key from under it. ‘This place belongs to a friend who lets me use it. I often stay here for a couple of weeks when I come back from…’

I wondered if he was going to mention his work.

‘When I come back from a job,’ he said. ‘I need a bit of time to… It’s hard to explain but being up here rinses the person I’ve been living out of me.’

The torchlight flickered over his face and I realised he was staring intently at me. Once again my breath vanished and my blood thinned until it felt as though my heart was beating water through my veins.

Who, I wondered, was left when the character he’d been living had drained away?

He unlocked the cabin door and we went into a dark room. Torchlight picked out bunk beds and an iron stove.

‘Close your eyes,’ Nick said.

I obeyed and he put his hands on my shoulders and guided me across the room and through a door. I felt the chill of a breeze on my skin and knew I was outside.

‘Count to fifty, then open them.’

His hands lingered on my shoulders and their warmth was the only thing I felt.

When I opened my eyes, a rush of glory made me gasp. No need to look up because we were already standing high on a wooden deck built into the mountainside. The sky wrapped the night all around us. It wasn’t the dark emptiness seen in the city. Instead it glimmered with millions of stars. Some were distinct and bright but most clustered together to create great washes of light sweeping through the air. It was a universe of beauty and the sheer vastness of it disorientated me. I felt as though I was falling through space and I staggered.

Nick’s hands tightened on my shoulders. ‘You understand why you couldn’t go home without seeing this.’

‘I do.’

He talked about the stars as we gazed. Names of constellations and how far away they were. How long the light had taken to reach us and how the earth moved through the cosmos like a giant ship, dragged this way and that as though by invisible currents and winds, so that the view changed with the hours and the seasons and the years. I listened but his words flowed through me so I remembered little of what he said. Only the tone of his voice, soft and quiet and so right in the face of such magnificence, stayed with me.

We watched for a long time until the chill reached my bones.

‘You’re shaking.’

‘I’m shivering. It’s freezing.’

‘Wait.’

He came back with a blanket and wrapped it round us both, gripping me tightly to his warmth. The trembling wouldn’t stop. So, in the end, I turned my back on the stars and wriggled round to face him. The starlight reflected in his eyes as his fingers traced the outline of my face.

I’d guessed right. His touch sent quivers along my skin.

‘Jenifry Shaw,’ he said.

I stretched up and kissed him.

I woke slowly. Clear, fresh morning light came through the open door leading onto the deck. The stove we’d lit at some point during the night had gone out but I was cocooned in the mess of bunk bed mattresses and blankets we’d pulled onto the floor. Memories of last night wafted through my thoughts and I smiled.

I was alone, though. Where was Nick? Definitely not in this one-roomed cabin.

His voice, impatient and almost angry, cut through my drowsiness. He was arguing with someone outside on the deck. On his phone, I realised as he strode past the door, dressed only in a pair of jeans. A faint sense of disappointment clouded my comfort. I should get up but I couldn’t be bothered to move. I caught glimpses of Nick as he walked up and down outside. He stopped eventually in the doorway and muttered explosive OKs down the phone as the skin on his back shifted with each breath and gleamed in the cold sunlight.

Tension seeped back into my muscles and tightened them. The tangle of rugs and mattresses looked tawdry in the cool morning light. The cabin’s wooden rafters dripped with cobwebs. I felt a sudden urge to go for a run then a long shower.

Nick came in.

‘We have to leave.’ His voice was impatient with barely controlled frustration.

‘Now?’

‘Yes.’ He made a big effort to speak calmly. ‘I’m sorry. But I have to go to London and fast. There’s a plane I must catch later today.’

‘Work?’ I asked but all I got in reply was a terse nod.

We flung our clothes on and tidied the cabin without speaking. We didn’t speak during the journey either but he was concentrating on driving as fast as he could, flinging the car round the bends we’d driven up so hopefully the night before. His phone automatically started playing music. Some playlist of great film themes. But he swore and switched it over to a Spanish talk radio station.

I felt a bit blank really.

‘I’m sorry,’ he said again as he pulled into the old farm where I parked my campervan. ‘If I had a choice, I wouldn’t go.’

A sneaky little voice murmured that there was always a choice.

‘No problem,’ I said.

‘You don’t mind then?’

‘Of course not.’

I suspected I was lying.

‘It should only be for a couple of days. Maybe three?’

It sounded like a question but I wasn’t sure. Go on, I thought, ask me if I’ll still be here. And, above all, tell me you hope I will be.

He didn’t but looked at me as though waiting for me to respond.

So far, I’d done all the running in this relationship – if you could call it that. I sodding well trekked all the way to Spain and came looking for him. I was even the one who made the first move last night. Well, I wasn’t going to hang around any longer unless he made an effort.

‘I might be gone when you get back,’ I said.

He muttered something under his breath.

‘What?’

‘You’ve satisfied your curiosity then,’ he said with an edge to his voice.

‘What do you mean?’

‘It doesn’t matter.’

‘Fine.’

I got out of the car and went to slam the door behind me but he reached out an arm and held it open.

‘Jen,’ he called.

I waited while he got out.

He pulled a hand through his hair. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said. ‘I don’t know what else to say. I’ll be back as soon as I can. I hate leaving things like this but I have to go now.’

‘Sure,’ I said and strode off into the hippies’ farm.

I might have cried if I hadn’t been so angry. With myself as much as with Nick.

I made tea, a fragrant brew of Indian spice-infused black tea, and sipped it. I should probably sleep but I didn’t think the emotions in my gut would let me. I was upset and I was angry about being upset because I had no reason to be. Nick had a job and he’d had to go do it. The timing was unfortunate, but last night had probably only been about sex. Nice but not important. Very nice… but still unimportant. It had been fun and the stargazing had been splendid but nothing more.

I should go home.

Except going home meant tackling all the things I’d put off to come here. I needed to find a job as my money wasn’t going to last forever. I needed to do something about my flat. I’d been going to sell it to get Kit out of a financial hole but Pa had come to the rescue instead. However, preparing to sell it had made me realise how little I wanted to stay in London. There were so many decisions I needed to make. So many dreary, life-sucking decisions.

And then I had a much better idea.

Three

I didn’t go home and I didn’t hang around for Nick. Instead I went back up into the sierras, to the crag I’d been climbing when I frightened myself. I parked on the road beneath, lugged my kit up the footpath through the pine forest to the top and set up anchors.

I spent a week preparing. First I explored the face, trying all the possible ways up until I was sure I’d found the best one. And then I climbed it, rapped down and climbed it again. And again and again. I refined every move, paring each one back until it was pure. I practised and practised until each sequence was imprinted on my brain and body. My life shrank down to the rock. I thought of nothing else. Not Nick. Not Ma. Not the future. I knew every fold and ripple of the rock, where it was rough and where it was smooth. I knew how it changed during the day. The chill of the edges in the morning when the sun threw oblique shadows and made every crack seem vast. In the evening the stone’s surface, warmed by the spring sun, caressed my skin as I moved up it. And when it got too dark to climb, I shut the door on the outside and lay on the bed and visualised each square foot of granite face and let my body curl and stretch in response.

I never looked at the night sky.

Nick called me in the café one evening. It was a dingy little place except for the colourful tiles on the floor. Empty apart from a cluster of old men at the bar, reading their newspapers and exchanging the occasional comment. It reminded me of the pub in Craighston, the village near my childhood home in Cornwall. That too had the same taciturn old men except their faces were whiter than the sun-dried faces of the men here.

‘I’m back,’ Nick said. ‘Are you still here? Angel told me he hadn’t seen you. If you’ve –’

‘I’m not in Alájar.’

‘Oh.’

‘But I’m not far. I’ve gone climbing.’

‘Of course.’

He paused as though waiting for me to say something.

‘How was your work trip?’ I asked.

‘Tricky.’

Silence.

‘You know I can’t talk much about it.’

I did but I didn’t like it.

More silence.

‘Are you coming back then?’

My turn to be quiet. Was I coming back? I still wasn’t sure. My head was full of the climb.

‘I could,’ I said.

‘I’d like that.’

‘I’ll text you.’

We tried to chat for a few minutes after that. A few details of where I was. How the chestnut trees were budding and the pigs getting fat. It’s tough to chat when neither of you can explain what you’ve been doing because one of you is forbidden from talking about it and the other is too scared of what she’s planning to give it words and both of you are wary of each other.

I ended the call, walked to the van and lay on the bed, but not even visualising the climb could completely banish Nick from my thoughts. In the end I took my sleeping bag and settled outside at the base of the crag with my back pressed against the rock. Sleep came. In the morning I knew it was now or never.

I tied the rope off out of the way and climbed without it.

It wasn’t difficult. I’d learned the moves so well they flowed through my body without my consciousness guiding them. There was no heart-stopping thrill, no wave of adrenalin racing through my blood but I felt alive in a way I never had before. The physicality overwhelmed me. I had no emotions. Not fear. Not excitement. Not even pride at each perfect placement of hand and foot. My head was empty except for the concentration on making each move as stark and simple as it could be and all I felt was my limbs moving with the stone as if we were dancers performing a perfect pas de deux.