7,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Bauer World Press

- Sprache: Englisch

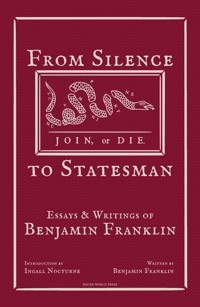

From Silence to Statesman: Essays & Writings of Benjamin Franklin offers an illuminating journey through the authentic words of one of America's most influential Founding Fathers. This meticulously curated collection presents Benjamin Franklin's essays and writings in their original form.

The book serves as a definitive resource for readers seeking to separate fact from fiction in Franklin's oft-misquoted wisdom. It includes many of his most famous works, alongside lesser-known but equally insightful pieces. Many entries are augmented by contextual information, providing readers with a deeper understanding of the historical and personal circumstances that shaped Franklin's thoughts.

The plenitude of work left behind by Franklin can be overwhelming, but the structure in which it’s presented in this book will offer a window into Franklin's mind. From his scientific observations to his political philosophy, readers will gain a comprehensive view of the man who helped shape a nation.

Whether you're a history buff, a quotation enthusiast, or simply curious about one of America's most celebrated figures, "From Silence to Statesman" provides an engaging and authoritative exploration of Benjamin Franklin's enduring legacy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Bauer World Press

From State to Statesman

Essays & Writings of Benjamin Franklin

Written by Benjamin Franklin

Introduction by Ingall Nocturne

Bauer World Press is a division of The Bauer Company™.

Bauer World Press furthers the Company's objective of excellence in historical research, education, and knowledge by publishing digital and paperback content worldwide.

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted.

First Published as a Bauer World Press Paperback 2024

All original additions are ©2024 by Bauer World Press and may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, by any form or any means, without the prior permission in writing of Bauer World Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be directed to the address below.

All rights reserved.

Paperback ISBN: 979-8-9920278-0-8

Hardcover ISBN: 979-8-9920278-2-2

Published in the United States of America by Bauer World Press

BAUER WORLD PRESS

Bauer World Press gladly makes available an array of literary treasures hailing from around the globe. In each accessible volume, Bauer World Press upholds its dedication to erudition by furnishing only the most authentic and original texts. Unwavering commitment to research and accuracy spans the breadth of our works, often augmented with commentary and context.

Our Works

All Quiet on the Western Front

The Art of Being Right: 38 Ways to Win an Argument

The Art of Money Getting: or, Golden Rules for Making Money

Common Sense

From Silence to Statesman: Essays & Writings of Benjamin Franklin

The Hardy Boys: Tower Treasure

The Life of Charlemagne: Vita Karoli Magni

The Trumpeter of Krakow

Contents

Introduction

If this is your initial exposure to the writings of Benjamin Franklin, I must inform you that you are opening a door which may not easily close. Diligent in his industry, Franklin's craft as a printer afforded him an outlet for the distillation and distribution of his accumulated wisdom. Operating as a seasoned engineer of writing mechanics, there exists in Franklin's work a thoughtful structure accompanying what is received by the reader as the appearance of fluid prose.

It was reading Charlie Munger, formerly the Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, where I grew intrigued about Franklin beyond common knowledge. Charlie seemed to reference Franklin every chance he could get when there was occasion for worldly wisdom. When journalist Becky Quick asked Charlie his thoughts on Franklin in an interview just months before his passing, Charlie had this to say: “He started in absolute poverty. He was almost entirely self-educated. To rise from that kind of a starting position, and become the best inventor in his country, the best scientist in his country, the best writer in his country, the best diplomat in his country—he was a very unusual person.” I soon found Franklin's reach extended to other eminent personalities such as Warren Buffett, Elon Musk, Jamie Dimon, and Bill Ackman.

Acting on Charlie's advice, I purchased a copy of The Autobiography. You'll be pleased to know that I shall refrain from boring you with the details regarding the immediate effects this book had on me; however, I ask you allow this brief thought: The impact of Franklin's work on the life of this individual has since been immeasurable. The value of The Autobiography, Poor Richard, and the contents herein of From Silence to Statesman, have been markedly generous in equipping my personage with invaluable knowledge, felicity, and solace. Perhaps it will do the same for you.

Upon reading the Autobiography or perusing Poor Richard, one might observe Franklin's proclivity toward dense and memorable bon mots. As a result his essays, penetrative as they are creative, are often overlooked. This is a shame, as Franklin's more comprehensive papers pack the same punch as their shorter counterparts. In the years since, a great deal of Franklin's work has been incorrectly reprinted, inaccurately ascribed, and in many cases—lost. Nor did Franklin make the task of accounting for his work particularly straightforward. He assumed identities such as Silence Dogood, The Busy-Body, Americanus, Arator, and a smattering of acronymic pseudonyms. Thanks to the efforts of historians, as well as Franklin's own family and acquaintances, namely his grandson, William Temple Franklin; we possess today a plenitude of works positively identified as being written by Franklin.

This book will bring together those works under one roof; original diction and punctuation maintained in their inaugural form. Denying the temptation to embark upon analysis of these papers, I default to a simple question: Were one to read a comprehensive film-review prior to viewing, can one expect to absorb the same novel experience as the impartial viewer? Any attempt at analysis here will certainly fall short, or worse, spoil the joys of a new read; a pleasure which I myself enjoyed, and shan't deny that pleasure to others.

Franklin's work could command a lifetime of study, fortunately there are those who have taken up the challenge. For the greatest insight into Franklin's life there is no book I could recommend more than Carl van Doren's 1939 Pulitzer Prize winning biography, Benjamin Franklin. For a thoughtfully composed selection of Poor Richard's greatest quotes, I would recommend the Peter Pauper Press version of Poor Richard's Almanack. Regarding full-editions of Poor Richard's Almanack, Bauer World Press will be publishing all Almanack's (1732-1758) as a sequential volume to this book in the upcoming year. If no such volume surfaces, presume us broke or perished.

In the arrangement of this text, it appeared initially suitable to topically categorise Franklin's writings. The problem that arose had to do with Franklin's polymathy. Even if one were to arrange Franklin's works by overarching themes of Philosophy, Science, Politics, Industry, Self-Improvement, et cetera; there is too much gradation in subject matter to definitively pigeonhole neat labels. Worse yet, ascribing such labels risks detracting from the nuance of the essays themselves. Alternatively, by arranging this work in order of chronological publication, the focus shifts to Franklin's development as a pansophic writer. Observe how his clarity and order of thought develop from the early letters of "Silence Dogood" up through more urgent critiques as in "Plain Truth." Observe the ways in which irreverence, satire, morality, and Socratic enquiry fortify his positions, epigrammatically appealing to a common logic that few are able to articulate with comparable brevity.

For those unfamiliar with Franklin's writing, the Silence Dogood Letters are a prime initiation into his burgeoning style. Writing under his own name in 1722 at a mere sixteen years-of-age, Franklin was denied publication in his brother's newspaper, The New-England Courant. Despite for making up in ability what he lacked in age, an escalating feud between Benjamin and the elder James meant that Franklin's likelihood of authorship grew increasingly bleak. In order to circumvent this, Franklin took up a habit that would continue throughout his life—publishing his work under pseudonymous personas.

The character of Silence Dogood was a middle-aged widow. She was virtuous, patriotic, and opinionated; expressing it all with a keen wit. Her commentary concerned a breadth of subjects most often having to do with, and critiquing, life in the Colonies. Franklin knew that an adolescent was unlikely to be taken seriously by the general public, an observation he touches on in the opening lines of the First Letter. But Silence Dogood? She possessed the benefit of years, living through the throes of fortune and misfortune; now humbly offering her findings to the general public over a series of Fourteen Letters.

The strain between Benjamin and his brother James continued. After Franklin anonymously published the Silence Dogood Letters, he determined it was time to carve his own way.

Upon running away from his native Boston to Philadelphia at the age of seventeen, Franklin sought work as a printer. As anyone working in Franklin's trade knew, the biggest name in town was Andrew Bradford. Not only was Bradford a printer and newspaper publisher, he was also Postmaster. This allowed him to distribute his newspapers throughout Pennsylvania essentially free of competition.

When Franklin attempted to land a job with the affluent printer, Bradford informed him no openings were available; however, he would introduce Franklin to a rival printer (of little consequence), Samuel Keimer. The London-born Keimer was mercurial, choleric, and worked with an old printing-press using worn out typefaces. Franklin, having come to Philadelphia without a pence in his pocket, begrudgingly took the job with Keimer. Once it came to light that Keimer’s eventual plans for a newspaper were no more than a ruse to retain Franklin's employ, he quit. Enticed by a series of empty-promises by the excitable and unreliable Sir William Keith, Franklin found himself working as a printer in London for the next eighteen months.

After returning to Philadelphia, Franklin and another of Keimer’s employees, Hugh Meredith, established a partnership creating their own printing press. The problem, however, was that they faced a great competitive disadvantage. Despite Keimer's business being poorly managed and accumulating debt, he was well-connected in Philadelphia. Even worse, Andrew Bradford had grown to become largest printer in Pennsylvania, receiving preferment as the official printer to the Pennsylvania Government.

Franklin knew they would have to work like never before to make a name for themselves; however, Meredith proved to not share the same ambitious qualities. In order to drum up business, Franklin found himself doubling-down on his connections within the Junto, an intellectual-social-club he’d founded years before. It was here an opportunity arose.

For three years, Keimer had been composing a publication of the Folio History of the Quakers by William Sewel for the local Quaker community. Joseph Breitnal, a Junto member, secured from the Quakers a portion of the Sewel publication to be printed by Franklin.

Franklin toiled through sleepless nights, pushing out page-after-page of the Folio, completing the contract in an astonishing forty days. “This industry, visible to our neighbours; began to give us character and credit-” said Franklin. This local credibility was crucial, as Franklin was planning his most ambitious move yet—the launch of a newspaper.

Upon hearing his ex-employee planned to enter the newspaper business, Keimer, notwithstanding his mounting debt, rushed to establish The Pennsylvania Gazette. Franklin possessed not the means nor the distribution to launch his newspaper in competition with Keimer. After Bradford’s successful American Weekly Mercury, there was hardly room for a second newspaper in Philadelphia, let alone a third.

So what did Franklin do? Instead of fighting the tide, he went with it. While it may appear counterintuitive, Franklin responded to Keimer’s launch by writing an anonymous series of letters for Bradford’s Mercury newspaper titled the Busy-Body. Indeed, while this may have increased the readership of the Mercury, it achieved Franklin’s ultimate goal, detracting readers from Keimer.

Similar to the Dogood Letters, the Busy-Body is straightforward and humourous. It was an opportunity for Franklin to express his position on ethics, values, and urge the general public toward the useful pursuit of knowledge. It was a commentary on life in Philadelphia, which Franklin believed readers would find reassuring and relatable. Lastly, it took subtle digs at Keimer. Even if readers weren’t aware to whom the Busy-Body specifically referred, Franklin’s penmanship was unmistakable to his former employer.

Keimer’s poor management and risky gambles compounded. He began evading his debtors and planned to flee Philadelphia for the sunny shores of Barbados. So, what was to become of the The Pennsylvania Gazette? Keimer had no choice but to find a buyer for his fledgling newspaper. Fortunately, a buyer stepped forward—Benjamin Franklin.

Ladies and Gentlemen, From Silence to Statesman

Ingall Nocturne

Part I

2 april, 1722 - 1726

Silence Dogood No. 1

Silence Dogood No. 2

Silence Dogood No. 3

Silence Dogood No. 4

Silence Dogood No. 6

Silence Dogood No. 8

Silence Dogood No. 12

Silence Dogood No. 14

On Titles of Honor

Plan for Attaining Moral Perfection

Silence Dogood, No. 1

2 April, 1722

To the Author of the New-England Courant.

Sir,

It may not be improper in the first place to inform your Readers, that I intend once a Fortnight to present them, by the Help of this Paper, with a short Epistle, which I presume will add somewhat to their Entertainment.

And since it is observed, that the Generality of People, now a days, are unwilling either to commend or dispraise what they read, until they are in some measure informed who or what the Author of it is, whether he be poor or rich, old or young, a Schollar or a Leather Apron Man, &c. and give their Opinion of the Performance, according to the Knowledge which they have of the Author’s Circumstances, it may not be amiss to begin with a short Account of my past Life and present Condition, that the Reader may not be at a Loss to judge whether or not my Lucubrations are worth his reading.

At the time of my Birth, my Parents were on Ship-board in their Way from London to N. England. My Entrance into this troublesome World was attended with the Death of my Father, a Misfortune, which tho’ I was not then capable of knowing, I shall never be able to forget; for as he, poor Man, stood upon the Deck rejoycing at my Birth, a merciless Wave entred the Ship, and in one Moment carry’d him beyond Reprieve. Thus, was the first Day which I saw, the last that was seen by my Father; and thus was my disconsolate Mother at once made both a Parent and a Widow.

When we arrived at Boston (which was not long after) I was put to Nurse in a Country Place, at a small Distance from the Town, where I went to School, and past my Infancy and Childhood in Vanity and Idleness, until I was bound out Apprentice, that I might no longer be a Charge to my Indigent Mother, who was put to hard Shifts for a Living.

My Master was a Country Minister, a pious good-natur’d young Man, and a Batchelor: He labour’d with all his Might to instil vertuous and godly Principles into my tender Soul, well knowing that it was the most suitable Time to make deep and lasting Impressions on the Mind, while it was yet untainted with Vice, free and unbiass’d. He endeavour’d that I might be instructed in all that Knowledge and Learning which is necessary for our Sex, and deny’d me no Accomplishment that could possibly be attained in a Country Place; such as all Sorts of Needle-Work, Writing, Arithmetick, &c. and observing that I took a more than ordinary Delight in reading ingenious Books, he gave me the free Use of his Library, which tho’ it was but small, yet it was well chose, to inform the Understanding rightly, and enable the Mind to frame great and noble Ideas.

Before I had liv’d quite two Years with this Reverend Gentleman, my indulgent Mother departed this Life, leaving me as it were by my self, having no Relation on Earth within my Knowledge.

I will not abuse your Patience with a tedious Recital of all the frivolous Accidents of my Life, that happened from this Time until I arrived to Years of Discretion, only inform you that I liv’d a chearful Country Life, spending my leisure Time either in some innocent Diversion with the neighbouring Females, or in some shady Retirement, with the best of Company, Books. Thus I past away the Time with a Mixture of Profit and Pleasure, having no affliction but what was imaginary, and created in my own Fancy; as nothing is more common with us Women, than to be grieving for nothing, when we have nothing else to grieve for.

As I would not engross too much of your Paper at once, I will defer the Remainder of my Story until my next Letter; in the mean time desiring your Readers to exercise their Patience, and bear with my Humours now and then, because I shall trouble them but seldom. I am not insensible of the Impossibility of pleasing all, but I would not willingly displease any; and for those who will take Offence where none is intended, they are beneath the Notice of Your Humble Servant,

Silence Dogood

Silence Dogood, No. 2

16 April, 1722

To the Author of the New-England Courant.

Sir,

Histories of Lives are seldom entertaining, unless they contain something either admirable or exemplar: And since there is little or nothing of this Nature in my own Adventures, I will not tire your Readers with tedious Particulars of no Consequence, but will briefly, and in as few Words as possible, relate the most material Occurrences of my Life, and according to my Promise, confine all to this Letter.

My Reverend Master who had hitherto remained a Batchelor, (after much Meditation on the Eighteenth verse of the Second Chapter of Genesis,) took up a Resolution to marry; and having made several unsuccessful fruitless Attempts on the more topping Sort of our Sex, and being tir’d with making troublesome Journeys and Visits to no Purpose, he began unexpectedly to cast a loving Eye upon Me, whom he had brought up cleverly to his Hand.

There is certainly scarce any Part of a Man’s Life in which he appears more silly and ridiculous, than when he makes his first Onset in Courtship. The aukward Manner in which my Master first discover’d his Intentions, made me, in spite of my Reverence to his Person, burst out into an unmannerly Laughter: However, having ask’d his Pardon, and with much ado compos’d my Countenance, I promis’d him I would take his Proposal into serious Consideration, and speedily give him an Answer.

As he had been a great Benefactor (and in a Manner a Father to me) I could not well deny his Request, when I once perceived he was in earnest. Whether it was Love, or Gratitude, or Pride, or all Three that made me consent, I know not; but it is certain, he found it no hard Matter, by the Help of his Rhetorick, to conquer my Heart, and perswade me to marry him.

This unexpected Match was very astonishing to all the Country round about, and served to furnish them with Discourse for a long Time after; some approving it, others disliking it, as they were led by their various Fancies and Inclinations.

We lived happily together in the Heighth of conjugal Love and mutual Endearments, for near Seven Years, in which Time we added Two likely Girls and a Boy to the Family of the Dogoods: But alas! When my Sun was in its meridian Altitude, inexorable unrelenting Death, as if he had envy’d my Happiness and Tranquility, and resolv’d to make me entirely miserable by the Loss of so good an Husband, hastened his Flight to the Heavenly World, by a sudden unexpected Departure from this.

I have now remained in a State of Widowhood for several Years, but it is a State I never much admir’d, and I am apt to fancy that I could be easily perswaded to marry again, provided I was sure of a good-humour’d, sober, agreeable Companion: But one, even with these few good Qualities, being hard to find, I have lately relinquish’d all Thoughts of that Nature.

At present I pass away my leisure Hours in Conversation, either with my honest Neighbour Rusticus and his Family, or with the ingenious Minister of our Town, who now lodges at my House, and by whose Assistance I intend now and then to beautify my Writings with a Sentence or two in the learned Languages, which will not only be fashionable, and pleasing to those who do not understand it, but will likewise be very ornamental.

I shall conclude this with my own Character, which (one would think) I should be best able to give. Know then, That I am an Enemy to Vice, and a Friend to Vertue. I am one of an extensive Charity, and a great Forgiver of private Injuries: A hearty Lover of the Clergy and all good Men, and a mortal Enemy to arbitrary Government and unlimited Power. I am naturally very jealous for the Rights and Liberties of my Country; and the least appearance of an Incroachment on those invaluable Priviledges, is apt to make my Blood boil exceedingly. I have likewise a natural Inclination to observe and reprove the Faults of others, at which I have an excellent Faculty. I speak this by Way of Warning to all such whose Offences shall come under my Cognizance, for I never intend to wrap my Talent in a Napkin. To be brief; I am courteous and affable, good humour’d (unless I am first provok’d,) and handsome, and sometimes witty, but always, Sir, Your Friend and Humble Servant,

Silence Dogood

Silence Dogood, No. 3

30 April, 1722

To the Author of the New-England Courant.

Sir,

It is undoubtedly the Duty of all Persons to serve the Country they live in, according to their Abilities; yet I sincerely acknowledge, that I have hitherto been very deficient in this Particular; whether it was for want of Will or Opportunity, I will not at present stand to determine: Let it suffice, that I now take up a Resolution, to do for the future all that lies in my Way for the Service of my Countrymen.

I have from my Youth been indefatigably studious to gain and treasure up in my Mind all useful and desireable Knowledge, especially such as tends to improve the Mind, and enlarge the Understanding: And as I have found it very beneficial to me, I am not without Hopes, that communicating my small Stock in this Manner, by Peace-meal to the Publick, may be at least in some Measure useful.

I am very sensible that it is impossible for me, or indeed any one Writer to please all Readers at once. Various Persons have different Sentiments; and that which is pleasant and delightful to one, gives another a Disgust. He that would (in this Way of Writing) please all, is under a Necessity to make his Themes almost as numerous as his Letters. He must one while be merry and diverting, then more solid and serious; one while sharp and satyrical, then (to mollify that) be sober and religious; at one Time let the Subject be Politicks, then let the next Theme be Love: Thus will every one, one Time or other find some thing agreeable to his own Fancy, and in his Turn be delighted.

According to this Method I intend to proceed, bestowing now and then a few gentle Reproofs on those who deserve them, not forgetting at the same time to applaud those whose Actions merit Commendation. And here I must not forget to invite the ingenious Part of your Readers, particularly those of my own Sex to enter into a Correspondence with me, assuring them, that their Condescension in this Particular shall be received as a Favour, and accordingly acknowledged.

I think I have now finish’d the Foundation, and I intend in my next to begin to raise the Building. Having nothing more to write at present, I must make the usual excuse in such Cases, of being in haste, assuring you that I speak from my Heart when I call my self, The most humble and obedient of all the Servants your Merits have acquir’d,

Silence Dogood

Silence Dogood, No. 4

14 May, 1722

An sum etiam nunc vel Graecè loqui vel Latinè docendus?1 Cicero.

To the Author of the New-England Courant.

Sir,

Discoursing the other Day at Dinner with my Reverend Boarder, formerly mention’d, (whom for Distinction sake we will call by the Name of Clericus,) concerning the Education of Children, I ask’d his Advice about my young Son William, whether or no I had best bestow upon him Academical Learning, or (as our Phrase is) bring him up at our College: He perswaded me to do it by all Means, using many weighty Arguments with me, and answering all the Objections that I could form against it; telling me withal, that he did not doubt but that the Lad would take his Learning very well, and not idle away his Time as too many there now-a-days do. These Words of Clericus gave me a Curiosity to inquire a little more strictly into the present Circumstances of that famous Seminary of Learning; but the Information which he gave me, was neither pleasant, nor such as I expected.

As soon as Dinner was over, I took a solitary Walk into my Orchard, still ruminating on Clericus’s Discourse with much Consideration, until I came to my usual Place of Retirement under the Great Apple-Tree; where having seated my self, and carelessly laid my Head on a verdant Bank, I fell by Degrees into a soft and undisturbed Slumber. My waking Thoughts remained with me in my Sleep, and before I awak’d again, I dreamt the following Dream.

I fancy’d I was travelling over pleasant and delightful Fields and Meadows, and thro’ many small Country Towns and Villages; and as I pass’d along, all Places resounded with the Fame of the Temple of Learning: Every Peasant, who had wherewithal, was preparing to send one of his Children at least to this famous Place; and in this Case most of them consulted their own Purses instead of their Childrens Capacities: So that I observed, a great many, yea, the most part of those who were travelling thither, were little better than Dunces and Blockheads. Alas! alas!

At length I entred upon a spacious Plain, in the Midst of which was erected a large and stately Edifice: It was to this that a great Company of Youths from all Parts of the Country were going; so stepping in among the Crowd, I passed on with them, and presently arrived at the Gate.

The Passage was kept by two sturdy Porters named Riches and Poverty, and the latter obstinately refused to give Entrance to any who had not first gain’d the Favour of the former; so that I observed, many who came even to the very Gate, were obliged to travel back again as ignorant as they came, for want of this necessary Qualification. However, as a Spectator I gain’d Admittance, and with the rest entred directly into the Temple.

In the Middle of the great Hall stood a stately and magnificent Throne, which was ascended to by two high and difficult Steps. On the Top of it sat Learning in awful State; she was apparelled wholly in Black, and surrounded almost on every Side with innumerable Volumes in all Languages. She seem’d very busily employ’d in writing something on half a Sheet of Paper, and upon Enquiry, I understood she was preparing a Paper, call’d, The New-England Courant. On her Right Hand sat English, with a pleasant smiling Countenance, and handsomely attir’d; and on her left were seated several Antique Figures with their Faces vail’d. I was considerably puzzl’d to guess who they were, until one informed me, (who stood beside me,) that those Figures on her left Hand were Latin, Greek, Hebrew, &c. and that they were very much reserv’d, and seldom or never unvail’d their Faces here, and then to few or none, tho’ most of those who have in this Place acquir’d so much Learning as to distinguish them from English, pretended to an intimate Acquaintance with them. I then enquir’d of him, what could be the Reason why they continued vail’d, in this Place especially: He pointed to the Foot of the Throne, where I saw Idleness, attended with Ignorance, and these (he informed me) were they, who first vail’d them, and still kept them so.

Now I observed, that the whole Tribe who entred into the Temple with me, began to climb the Throne; but the Work proving troublesome and difficult to most of them, they withdrew their Hands from the Plow, and contented themselves to sit at the Foot, with Madam Idleness and her Maid Ignorance, until those who were assisted by Diligence and a docible Temper, had well nigh got up the first Step: But the Time drawing nigh in which they could no way avoid ascending, they were fain to crave the Assistance of those who had got up before them, and who, for the Reward perhaps of a Pint of Milk, or a Piece of Plumb-Cake, lent the Lubbers a helping Hand, and sat them in the Eye of the World, upon a Level with themselves.

The other Step being in the same Manner ascended, and the usual Ceremonies at an End, every Beetle-Scull seem’d well satisfy’d with his own Portion of Learning, tho’ perhaps he was e’en just as ignorant as ever. And now the Time of their Departure being come, they march’d out of Doors to make Room for another Company, who waited for Entrance: And I, having seen all that was to be seen, quitted the Hall likewise, and went to make my Observations on those who were just gone out before me.

Some I perceiv’d took to Merchandizing, others to Travelling, some to one Thing, some to another, and some to Nothing; and many of them from henceforth, for want of Patrimony, liv’d as poor as Church Mice, being unable to dig, and asham’d to beg, and to live by their Wits it was impossible. But the most Part of the Crowd went along a large beaten Path, which led to a Temple at the further End of the Plain, call’d, The Temple of Theology. The Business of those who were employ’d in this Temple being laborious and painful, I wonder’d exceedingly to see so many go towards it; but while I was pondering this Matter in my Mind, I spy’d Pecunia behind a Curtain, beckoning to them with her Hand, which Sight immediately satisfy’d me for whose Sake it was, that a great Part of them (I will not say all) travel’d that Road. In this Temple I saw nothing worth mentioning, except the ambitious and fraudulent Contrivances of Plagius, who (notwithstanding he had been severely reprehended for such Practices before) was diligently transcribing some eloquent Paragraphs out of Tillotson’s Works, &c., to embellish his own.

Now I bethought my self in my Sleep, that it was Time to be at Home, and as I fancy’d I was travelling back thither, I reflected in my Mind on the extream Folly of those Parents, who, blind to their Childrens Dulness, and insensible of the Solidity of their Skulls, because they think their Purses can afford it, will needs send them to the Temple of Learning, where, for want of a suitable Genius, they learn little more than how to carry themselves handsomely, and enter a Room genteely, (which might as well be acquir’d at a Dancing-School,) and from whence they return, after Abundance of Trouble and Charge, as great Blockheads as ever, only more proud and self-conceited.

While I was in the midst of these unpleasant Reflections, Clericus (who with a Book in his Hand was walking under the Trees) accidentally awak’d me; to him I related my Dream with all its Particulars, and he, without much Study, presently interpreted it, assuring me, That it was a lively Representation of Harvard College, Etcetera. I remain, Sir, Your Humble Servant,

Silence Dogood

1.Must I still be taught either to speak Greek or Latin?

Silence Dogood, No. 6

11 June, 1722

Quem Dies videt veniens Superbum,Hunc Dies vidit fugiens jacentem.1 Seneca.

To the Author of the New-England Courant.

Sir,

Among the many reigning Vices of the Town which may at any Time come under my Consideration and Reprehension, there is none which I am more inclin’d to expose than that of Pride. It is acknowledg’d by all to be a Vice the most hateful to God and Man. Even those who nourish it in themselves, hate to see it in others. The proud Man aspires after Nothing less than an unlimited Superiority over his Fellow-Creatures. He has made himself a King in Soliloquy; fancies himself conquering the World; and the Inhabitants thereof consulting on proper Methods to acknowledge his Merit. I speak it to my Shame, I my self was a Queen from the Fourteenth to the Eighteenth Year of my Age, and govern’d the World all the Time of my being govern’d by my Master. But this speculative Pride may be the Subject of another Letter: I shall at present confine my Thoughts to what we call Pride of Apparel. This Sort of Pride has been growing upon us ever since we parted with our Homespun Cloaths for Fourteen Penny Stuffs, &c. And the Pride of Apparel has begot and nourish’d in us a Pride of Heart, which portends the Ruin of Church and State. Pride goeth before Destruction, and a haughty Spirit before a Fall: And I remember my late Reverend Husband would often say upon this Text, That a Fall was the natural Consequence, as well as Punishment of Pride. Daily Experience is sufficient to evince the Truth of this Observation. Persons of small Fortune under the Dominion of this Vice, seldom consider their Inability to maintain themselves in it, but strive to imitate their Superiors in Estate, or Equals in Folly, until one Misfortune comes upon the Neck of another, and every Step they take is a Step backwards. By striving to appear rich they become really poor, and deprive themselves of that Pity and Charity which is due to the humble poor Man, who is made so more immediately by Providence.

This Pride of Apparel will appear the more foolish, if we consider, that those airy Mortals, who have no other Way of making themselves considerable but by gorgeous Apparel, draw after them Crowds of Imitators, who hate each other while they endeavour after a Similitude of Manners. They destroy by Example, and envy one another’s Destruction.

I cannot dismiss this Subject without some Observations on a particular Fashion now reigning among my own Sex, the most immodest and inconvenient of any the Art of Woman has invented, namely, that of Hoop-Petticoats. By these they are incommoded in their General and Particular Calling, and therefore they cannot answer the Ends of either necessary or ornamental Apparel. These monstrous topsy-turvy Mortar-Pieces, are neither fit for the Church, the Hall, or the Kitchen; and if a Number of them were well mounted on Noddles-Island, they would look more like Engines of War for bombarding the Town, than Ornaments of the Fair Sex. An honest Neighbour of mine, happening to be in Town some time since on a publick Day, inform’d me, that he saw four Gentlewomen with their Hoops half mounted in a Balcony, as they withdrew to the Wall, to the great Terror of the Militia, who (he thinks) might attribute their irregular Volleys to the formidable Appearance of the Ladies Petticoats.

I assure you, Sir, I have but little Hopes of perswading my Sex, by this Letter, utterly to relinquish the extravagant Foolery, and Indication of Immodesty, in this monstrous Garb of their’s; but I would at least desire them to lessen the Circumference of their Hoops, and leave it with them to consider, Whether they, who pay no Rates or Taxes, ought to take up more Room in the King’s High-Way, than the Men, who yearly contribute to the Support of the Government. I am, Sir, Your Humble Servant,

Silence Dogood

1. Whom the Day sees coming proudly, This Day sees fleeing, lying low.

Silence Dogood, No. 8

9 July, 1722

To the Author of the New-England Courant.

Sir,

I prefer the following Abstract from the London Journal to any Thing of my own, and therefore shall present it to your Readers this week without any further Preface.

“Without Freedom of Thought, there can be no such Thing as Wisdom; and no such Thing as publick Liberty, without Freedom of Speech; which is the Right of every Man, as far as by it, he does not hurt or controul the Right of another: And this is the only Check it ought to suffer, and the only Bounds it ought to know.

“This sacred Privilege is so essential to free Governments, that the Security of Property, and the Freedom of Speech always go together; and in those wretched Countries where a Man cannot call his Tongue his own, he can scarce call any Thing else his own. Whoever would overthrow the Liberty of a Nation, must begin by subduing the Freeness of Speech; a Thing terrible to Publick Traytors.

“This Secret was so well known to the Court of King Charles the First, that his wicked Ministry procured a Proclamation, to forbid the People to talk of Parliaments, which those Traytors had laid aside. To assert the undoubted Right of the Subject, and defend his Majesty’s legal Prerogative, was called Disaffection, and punished as Sedition. Nay, People were forbid to talk of Religion in their Families: For the Priests had combined with the Ministers to cook up Tyranny, and suppress Truth and the Law, while the late King James, when Duke of York, went avowedly to Mass, Men were fined, imprisoned and undone, for saying he was a Papist: And that King Charles the Second might live more securely a Papist, there was an Act of Parliament made, declaring it Treason to say that he was one.

“That Men ought to speak well of their Governours is true, while their Governours deserve to be well spoken of; but to do publick Mischief, without hearing of it, is only the Prerogative and Felicity of Tyranny: A free People will be shewing that they are so, by their Freedom of Speech.

“The Administration of Government, is nothing else but the Attendance of the Trustees of the People upon the Interest and Affairs of the People: And as it is the Part and Business of the People, for whose Sake alone all publick Matters are, or ought to be transacted, to see whether they be well or ill transacted; so it is the Interest, and ought to be the Ambition, of all honest Magistrates, to have their Deeds openly examined, and publickly scann’d: Only the wicked Governours of Men dread what is said of them; Audivit Tiberius probra queis lacerabitur, atque perculsus est1. The publick Censure was true, else he had not felt it bitter.

“Freedom of Speech is ever the Symptom, as well as the Effect of a good Government. In old Rome, all was left to the Judgment and Pleasure of the People, who examined the publick Proceedings with such Discretion, and censured those who administred them with such Equity and Mildness, that in the space of Three Hundred Years, not five publick Ministers suffered unjustly. Indeed whenever the Commons proceeded to Violence, the great Ones had been the Agressors.

“Guilt only dreads Liberty of Speech, which drags it out of its lurking Holes, and exposes its Deformity and Horrour to Daylight. Horatius, Valerius, Cincinnatus, and other vertuous and undesigning Magistrates of the Roman Commonwealth, had nothing to fear from Liberty of Speech. Their virtuous Administration, the more it was examin’d, the more it brightned and gain’d by Enquiry. When Valerius in particular, was accused upon some slight grounds of affecting the Diadem; he, who was the first Minister of Rome, does not accuse the People for examining his Conduct, but approved his Innocence in a Speech to them; and gave such Satisfaction to them, and gained such Popularity to himself, that they gave him a new Name; inde cognomenfactum Publicolae est2; to denote that he was their Favourite and their Friend. Latae deinde leges—Ante omnes de provocatione3Adversus Magistratus Ad Populum4, Livii, lib. 2. Cap. 8.

“But Things afterwards took another Turn. Rome, with the Loss of its Liberty, lost also its Freedom of Speech; then Mens Words began to be feared and watched; and then first began the poysonous Race of Informers, banished indeed under the righteous Administration of Titus, Narva, Trajan, Aurelius, &c. but encouraged and enriched under the vile Ministry of Sejanus, Tigillinus, Pallas, and Cleander: Queri libet, quod in secreta nostra non inquirant principes, nisi quos Odimus5, says Pliny to Trajan.

“The best Princes have ever encouraged and promoted Freedom of Speech; they know that upright Measures would defend themselves, and that all upright Men would defend them. Tacitus, speaking of the Reign of some of the Princes above mention’d, says with Extasy, Rara Temporum felicitate, ubi sentire quae velis, & quae sentias dicere licet: A blessed Time when you might think what you would, and speak what you thought.

“I doubt not but old Spencer and his Son, who were the Chief Ministers and Betrayers of Edward the Second, would have been very glad to have stopped the Mouths of all the honest Men in England. They dreaded to be called Traytors, because they were Traytors. And I dare say, Queen Elizabeth’s Walsingham, who deserved no Reproaches, feared none. Misrepresentation of publick Measures is easily overthrown, by representing publick Measures truly; when they are honest, they ought to be publickly known, that they may be publickly commended; but if they are knavish or pernicious, they ought to be publickly exposed, in order to be publickly detested.” Yours, &c.,

Silence Dogood

1.Tiberius heard the insults with which he was being torn apart, and he was struck with fear.

2.From this, the name Publicola was made.Publicola translates to "friend of the people."

3.Subsequently, laws were passed—Above all, concerning the right of appeal.

4.Against the Magistrate to the People

5.It is permissible to complain because our leaders do not inquire into our secrets, except those we hate.

Silence Dogood, No. 10

13 August, 1722

Optimè societas hominum servabitur.1 Cic.

To the Author of the New-England Courant.

Sir,

Discoursing lately with an intimate Friend of mine of the lamentable Condition of Widows, he put into my Hands a Book, wherein the ingenious Author proposes (I think) a certain Method for their Relief. I have often thought of some such Project for their Benefit my self, and intended to communicate my Thoughts to the Publick; but to prefer my own Proposals to what follows, would be rather an Argument of Vanity in me than Good Will to the many Hundreds of my Fellow-Sufferers now in New-England.

“We have (says he) abundance of Women, who have been Bred well, and Liv’d well, Ruin’d in a few Years, and perhaps, left Young, with a House full of Children, and nothing to Support them; which falls generally upon the Wives of the Inferior Clergy, or of Shopkeepers and Artificers.

“They marry Wives with perhaps £300 to £1000 Portion, and can settle no Jointure upon them; either they are Extravagant and Idle, and Waste it, or Trade decays, or Losses, or a Thousand Contingences happen to bring a Tradesman to Poverty, and he Breaks; the Poor Young Woman, it may be, has Three or Four Children, and is driven to a thousand shifts, while he lies in the Mint or Fryars under the Dilemma of a Statute of Bankrupt; but if he Dies, then she is absolutely Undone, unless she has Friends to go to.

“Suppose an Office to be Erected, to be call’d An Office of Ensurance for Widows, upon the following Conditions;

“Two thousand Women, or their Husbands for them, Enter their Names into a Register to be kept for that purpose, with the Names, Age, and Trade of their Husbands, with the Place of their abode, Paying at the Time of their Entring 5s.down with 1s. 4d. per Quarter, which is to the setting up and support of an Office with Clerks, and all proper Officers for the same; for there is no maintaining such without Charge; they receive every one of them a Certificate, Seal’d by the Secretary of the Office, and Sign’d by the Governors, for the Articles hereafter mentioned.

“If any one of the Women becomes a Widow, at any Time after Six Months from the Date of her Subscription, upon due Notice given, and Claim made at the Office in form, as shall be directed, she shall receive within Six Months after such Claim made, the Sum of £500 in Money, without any Deductions, saving some small Fees to the Officers, which the Trustees must settle, that they may be known.

“In Consideration of this, every Woman so Subscribing, Obliges her self to Pay as often as any Member of the Society becomes a Widow, the due Proportion or Share allotted to her to Pay, towards the £500 for the said Widow, provided her Share does not exceed the Sum of 5s.

“No Seamen or Soldiers Wives to be accepted into such a Proposal as this, on the Account before mention’d, because the Contingences of their Lives are not equal to others, unless they will admit this general Exception, supposing they do not Die out of the Kingdom.

“It might also be an Exception, That if the Widow, that Claim’d, had really, bona fide, left her by her Husband to her own use, clear of all Debts and Legacies, £2000 she shou’d have no Claim; the Intent being to Aid the Poor, not add to the Rich. But there lies a great many Objections against such an Article: As

“1. It may tempt some to forswear themselves.

“2. People will Order their Wills so as to defraud the Exception.

“One Exception must be made; and that is, Either very unequal Matches, as when a Woman of Nineteen Marries an old Man of Seventy; or Women who have infirm Husbands, I mean known and publickly so. To remedy which, Two things are to be done.

“1. The Office must have moving Officers without doors, who shall inform themselves of such matters, and if any such Circumstances appear, the Office should have 14 days time to return their Money, and declare their Subscriptions Void.

“2. No Woman whose Husband had any visible Distemper, should claim under a Year after her Subscription.

“One grand Objection against this Proposal, is, How you will oblige People to pay either their Subscription, or their Quarteridge.

“To this I answer, By no Compulsion (tho’ that might be perform’d too) but altogether voluntary; only with this Argument to move it, that if they do not continue their Payments, they lose the Benefit of their past Contributions.

“I know it lies as a fair Objection against such a Project as this, That the number of Claims are so uncertain, That no Body knows what they engage in, when they Subscribe, for so many may die Annually out of Two Thousand, as may perhaps make my Payment £20 or 25 per Ann., and if a Woman happen to Pay that for Twenty Years, though she receives the £500 at last she is a great Loser; but if she dies before her Husband, she has lessened his Estate considerably, and brought a great Loss upon him.

“First, I say to this, That I wou’d have such a Proposal as this be so fair and easy, that if any Person who had Subscrib’d found the Payments too high, and the Claims fall too often, it shou’d be at their Liberty at any Time, upon Notice given, to be released and stand Oblig’d no longer; and if so, Volenti non fit Injuria; every one knows best what their own Circumstances will bear.

“In the next Place, because Death is a Contingency, no Man can directly Calculate, and all that Subscribe must take the Hazard; yet that a Prejudice against this Notion may not be built on wrong Grounds, let’s examine a little the Probable hazard, and see how many shall die Annually out of 2000 Subscribers, accounting by the common proportion of Burials, to the number of the Living.

“Sir William Petty in his Political Arithmetick, by a very Ingenious Calculation, brings the Account of Burials in London, to be 1 in 40 Annually, and proves it by all the proper Rules of proportion’d Computation; and I’le take my Scheme from thence. If then One in Forty of all the People in England should Die, that supposes Fifty to Die every Year out of our Two Thousand Subscribers; and for a Woman to Contribute 5s. to every one, would certainly be to agree to Pay £12 10s. per Ann. upon her Husband’s Life, to receive £500 when he Di’d, and lose it if she Di’d first; and yet this wou’d not be a hazard beyond reason too great for the Gain.

“But I shall offer some Reasons to prove this to be impossible in our Case; First, Sir William Petty allows the City of London to contain about a Million of People, and our Yearly Bill of Mortality never yet amounted to 25000 in the most Sickly Years we have had, Plague Years excepted, sometimes but to 20000, which is but One in Fifty: Now it is to be consider’d here, that Children and Ancient People make up, one time with another, at least one third of our Bills of Mortality; and our Assurances lies upon none but the Midling Age of the People, which is the only age wherein Life is any thing steady; and if that be allow’d, there cannot Die by his Computation, above One in Eighty of such People, every Year; but because I would be sure to leave Room for Casualty, I’le allow one in Fifty shall Die out of our Number Subscrib’d.

“Secondly, It must be allow’d, that our Payments falling due only on the Death of Husbands, this One in Fifty must not be reckoned upon the Two thousand; for ’tis to be suppos’d at least as many Women shall die as Men, and then there is nothing to Pay; so that One in Fifty upon One Thousand, is the most that I can suppose shall claim the Contribution in a Year, which is Twenty Claims a Year at 5s. each, and is £5 per Ann. and if a Woman pays this for Twenty Year, and claims at last, she is Gainer enough, and no extraordinary Loser if she never claims at all: And I verily believe any Office might undertake to demand at all Adventures not above £6 per Ann. and secure the Subscriber £500 in case she come to claim as a Widow.”

I would leave this to the Consideration of all who are concern’d for their own or their Neighbour’s Temporal Happiness; and I am humbly of Opinion, that the Country is ripe for many such Friendly Societies, whereby every Man might help another, without any Disservice to himself. We have many charitable Gentlemen who Yearly give liberally to the Poor, and where can they better bestow their Charity than on those who become so by Providence, and for ought they know on themselves. But above all, the Clergy have the most need of coming into some such Project as this. They as well as poor Men (according to the Proverb) generally abound in Children; and how many Clergymen in the Country are forc’d to labour in their Fields, to keep themselves in a Condition above Want? How then shall they be able to leave any thing to their forsaken, dejected, and almost forgotten Wives and Children. For my own Part, I have nothing left to live on, but Contentment and a few Cows; and tho’ I cannot expect to be reliev’d by this Project, yet it would be no small Satisfaction to me to see it put in Practice for the Benefit of others. I am, Sir, &c.

Silence Dogood

1.The society of men will be best preserved.

Silence Dogood, No. 12

10 September, 1722

Quod est in cordi sobrii, est in ore ebrii.1

To the Author of the New-England Courant.

Sir,

It is no unprofitable tho’ unpleasant Pursuit, diligently to inspect and consider the Manners and Conversation of Men, who, insensible of the greatest Enjoyments of humane Life, abandon themselves to Vice from a false Notion of Pleasure and good Fellowship. A true and natural Representation of any Enormity, is often the best Argument against it and Means of removing it, when the most severe Reprehensions alone, are found ineffectual.

I would in this letter improve the little Observation I have made on the Vice of Drunkeness, the better to reclaim the good Fellows who usually pay the Devotions of the Evening to Bacchus.