I. AUNT CYNTHIA'S PERSIAN CAT

II. THE MATERIALIZING OF CECIL

III. HER FATHER'S DAUGHTER

IV. JANE'S BABY

V. THE DREAM-CHILD

VI. THE BROTHER WHO FAILED

VII. THE RETURN OF HESTER

VIII. THE LITTLE BROWN BOOK OF MISS EMILY

IX. SARA'S WAY

X. THE SON OF HIS MOTHER

XI. THE EDUCATION OF BETTY

XII. IN HER SELFLESS MOOD

XIII. THE CONSCIENCE CASE OF DAVID BELL

XIV. ONLY A COMMON FELLOW

XV. TANNIS OF THE FLATS

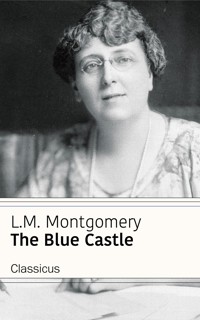

INTRODUCTION

It

is no exaggeration to say that what Longfellow did for Acadia, Miss

Montgomery has done for Prince Edward Island. More than a million

readers, young people as well as their parents and uncles and

aunts,

possess in the picture-galleries of their memories the exquisite

landscapes of Avonlea, limned with as poetic a pencil as Longfellow

wielded when he told the ever-moving story of Grand Pre.Only

genius of the first water has the ability to conjure up such a

character as Anne Shirley, the heroine of Miss Montgomery's first

novel, "Anne of Green Gables," and to surround her with

people so distinctive, so real, so true to psychology. Anne is as

lovable a child as lives in all fiction. Natasha in Count Tolstoi's

great novel, "War and Peace," dances into our ken, with

something of the same buoyancy and naturalness; but into what a

commonplace young woman she develops! Anne, whether as the gay

little

orphan in her conquest of the master and mistress of Green Gables,

or

as the maturing and self-forgetful maiden of Avonlea, keeps up to

concert-pitch in her charm and her winsomeness. There is nothing in

her to disappoint hope or imagination.Part

of the power of Miss Montgomery—and the largest part—is due to

her skill in compounding humor and pathos. The humor is honest and

golden; it never wearies the reader; the pathos is never

sentimentalized, never degenerates into bathos, is never morbid.

This

combination holds throughout all her works, longer or shorter, and

is

particularly manifest in the present collection of fifteen short

stories, which, together with those in the first volume of the

Chronicles of Avonlea, present a series of piquant and fascinating

pictures of life in Prince Edward Island.The

humor is shown not only in the presentation of quaint and unique

characters, but also in the words which fall from their mouths.

Aunt

Cynthia "always gave you the impression of a full-rigged ship

coming gallantly on before a favorable wind;" no further

description is needed—only one such personage could be found in

Avonlea. You would recognize her at sight. Ismay Meade's

disposition

is summed up when we are told that she is "good at having

presentiments—after things happen." What cleverer embodiment

of innate obstinacy than in Isabella Spencer—"a wisp of a

woman who looked as if a breath would sway her but was so set in

her

ways that a tornado would hardly have caused her to swerve an inch

from her chosen path;" or than in Mrs. Eben Andrews (in "Sara's

Way") who "looked like a woman whose opinions were always

very decided and warranted to wear!"This

gift of characterization in a few words is lavished also on

material

objects, as, for instance; what more is needed to describe the

forlornness of the home from which Anne was rescued than the

statement that even the trees around it "looked like

orphans"?The

poetic touch, too, never fails in the right place and is never too

frequently introduced in her descriptions. They throw a glamor over

that Northern land which otherwise you might imagine as rather cold

and barren. What charming Springs they must have there! One sees

all

the fruit-trees clad in bridal garments of pink and white; and what

a

translucent sky smiles down on the ponds and the reaches of bay and

cove!"The

Eastern sky was a great arc of crystal, smitten through with

auroral

crimsonings.""She

was as slim and lithe as a young white-stemmed birch-tree; her hair

was like a soft dusky cloud, and her eyes were as blue as Avonlea

Harbor in a fair twilight, when all the sky is a-bloom over

it."Sentiment

with a humorous touch to it prevails in the first two stories of

the

present book. The one relates to the disappearance of a valuable

white Persian cat with a blue spot in its tail. "Fatima" is

like the apple of her eye to the rich old aunt who leaves her with

two nieces, with a stern injunction not to let her out of the

house.

Of course both Sue and Ismay detest cats; Ismay hates them, Sue

loathes them; but Aunt Cynthia's favor is worth preserving. You

become as much interested in Fatima's fate as if she were your own

pet, and the climax is no less unexpected than it is natural,

especially when it is made also the last act of a pretty comedy of

love.Miss

Montgomery delights in depicting the romantic episodes hidden in

the

hearts of elderly spinsters as, for instance, in the case of

Charlotte Holmes, whose maid Nancy would have sent for the doctor

and

subjected her to a porous plaster while waiting for him, had she

known that up stairs there was a note-book full of original poems.

Rather than bear the stigma of never having had a love-affair, this

sentimental lady invents one to tell her mocking young friends. The

dramatic and unexpected denouement is delightful fun.Another

note-book reveals a deeper romance in the case of Miss Emily; this

is

related by Anne of Green Gables, who once or twice flashes across

the

scene, though for the most part her friends and neighbors at White

Sands or Newbridge or Grafton as well as at Avonlea are the persons

involved.In

one story, the last, "Tannis of the Flats," the secret of

Elinor Blair's spinsterhood is revealed in an episode which carries

the reader from Avonlea to Saskatchewan and shows the unselfish

devotion of a half-breed Indian girl. The story is both poignant

and

dramatic. Its one touch of humor is where Jerome Carey curses his

fate in being compelled to live in that desolate land in "the

picturesque language permissible in the far Northwest."Self-sacrifice,

as the real basis of happiness, is a favorite theme in Miss

Montgomery's fiction. It is raised to the nth power in the story

entitled, "In Her Selfless Mood," where an ugly, misshapen

girl devotes her life and renounces marriage for the sake of

looking

after her weak and selfish half-brother. The same spirit is found

in

"Only a Common Fellow," who is haloed with a certain

splendor by renouncing the girl he was to marry in favor of his old

rival, supposed to have been killed in France, but happily

delivered

from that tragic fate.Miss

Montgomery loves to introduce a little child or a baby as a solvent

of old feuds or domestic quarrels. In "The Dream Child," a

foundling boy, drifting in through a storm in a dory, saves a

heart-broken mother from insanity. In "Jane's Baby," a

baby-cousin brings reconciliation between the two sisters, Rosetta

and Carlotta, who had not spoken for twenty years because "the

slack-twisted" Jacob married the younger of the two.Happiness

generally lights up the end of her stories, however tragic they may

set out to be. In "The Son of His Mother," Thyra is a stern

woman, as "immovable as a stone image." She had only one

son, whom she worshipped; "she never wanted a daughter, but she

pitied and despised all sonless women." She demanded absolute

obedience from Chester—not only obedience, but also utter

affection, and she hated his dog because the boy loved him: "She

could not share her love even with a dumb brute." When Chester

falls in love, she is relentless toward the beautiful young girl

and

forces Chester to give her up. But a terrible sorrow brings the old

woman and the young girl into sympathy, and unspeakable joy is born

of the trial.Happiness

also comes to "The Brother who Failed." The Monroes had all

been successful in the eyes of the world except Robert: one is a

millionaire, another a college president, another a famous singer.

Robert overhears the old aunt, Isabel, call him a total failure,

but,

at the family dinner, one after another stands up and tells how

Robert's quiet influence and unselfish aid had started them in

their

brilliant careers, and the old aunt, wiping the tears from her

eyes,

exclaims: "I guess there's a kind of failure that's the best

success."In

one story there is an element of the supernatural, when Hester, the

hard older sister, comes between Margaret and her lover and, dying,

makes her promise never to become Hugh Blair's wife, but she comes

back and unites them. In this, Margaret, just like the delightful

Anne, lives up to the dictum that "nothing matters in all God's

universe except love." The story of the revival at Avonlea has

also a good moral.There

is something in these continued Chronicles of Avonlea, like the

delicate art which has made "Cranford" a classic: the

characters are so homely and homelike and yet tinged with beautiful

romance! You feel that you are made familiar with a real town and

its

real inhabitants; you learn to love them and sympathize with them.

Further Chronicles of Avonlea is a book to read; and to

know.NATHAN

HASKELL DOLE.

I. AUNT CYNTHIA'S PERSIAN CAT

Max

always blesses the animal when it is referred to; and I don't deny

that things have worked together for good after all. But when I

think

of the anguish of mind which Ismay and I underwent on account of

that

abominable cat, it is not a blessing that arises uppermost in my

thoughts.I

never was fond of cats, although I admit they are well enough in

their place, and I can worry along comfortably with a nice,

matronly

old tabby who can take care of herself and be of some use in the

world. As for Ismay, she hates cats and always did.But

Aunt Cynthia, who adored them, never could bring herself to

understand that any one could possibly dislike them. She firmly

believed that Ismay and I really liked cats deep down in our

hearts,

but that, owing to some perverse twist in our moral natures, we

would

not own up to it, but willfully persisted in declaring we

didn't.Of

all cats I loathed that white Persian cat of Aunt Cynthia's. And,

indeed, as we always suspected and finally proved, Aunt herself

looked upon the creature with more pride than affection. She would

have taken ten times the comfort in a good, common puss that she

did

in that spoiled beauty. But a Persian cat with a recorded pedigree

and a market value of one hundred dollars tickled Aunt Cynthia's

pride of possession to such an extent that she deluded herself into

believing that the animal was really the apple of her eye.It

had been presented to her when a kitten by a missionary nephew who

had brought it all the way home from Persia; and for the next three

years Aunt Cynthia's household existed to wait on that cat, hand

and

foot. It was snow-white, with a bluish-gray spot on the tip of its

tail; and it was blue-eyed and deaf and delicate. Aunt Cynthia was

always worrying lest it should take cold and die. Ismay and I used

to

wish that it would—we were so tired of hearing about it and its

whims. But we did not say so to Aunt Cynthia. She would probably

never have spoken to us again and there was no wisdom in offending

Aunt Cynthia. When you have an unencumbered aunt, with a fat bank

account, it is just as well to keep on good terms with her, if you

can. Besides, we really liked Aunt Cynthia very much—at times. Aunt

Cynthia was one of those rather exasperating people who nag at and

find fault with you until you think you are justified in hating

them,

and who then turn round and do something so really nice and kind

for

you that you feel as if you were compelled to love them dutifully

instead.So

we listened meekly when she discoursed on Fatima—the cat's name was

Fatima—and, if it was wicked of us to wish for the latter's

decease, we were well punished for it later on.One

day, in November, Aunt Cynthia came sailing out to Spencervale. She

really came in a phaeton, drawn by a fat gray pony, but somehow

Aunt

Cynthia always gave you the impression of a full rigged ship coming

gallantly on before a favorable wind.That

was a Jonah day for us all through. Everything had gone wrong.

Ismay

had spilled grease on her velvet coat, and the fit of the new

blouse

I was making was hopelessly askew, and the kitchen stove smoked and

the bread was sour. Moreover, Huldah Jane Keyson, our tried and

trusty old family nurse and cook and general "boss," had

what she called the "realagy" in her shoulder; and, though

Huldah Jane is as good an old creature as ever lived, when she has

the "realagy" other people who are in the house want to get

out of it and, if they can't, feel about as comfortable as St.

Lawrence on his gridiron.And

on top of this came Aunt Cynthia's call and request."Dear

me," said Aunt Cynthia, sniffing, "don't I smell smoke?You

girls must manage your range very badly. Mine never smokes.But

it is no more than one might expect when two girls try tokeep

house without a man about the place.""We

get along very well without a man about the place," I said

loftily. Max hadn't been in for four whole days and, though nobody

wanted to see him particularly, I couldn't help wondering why. "Men

are nuisances.""I

dare say you would like to pretend you think so," said Aunt

Cynthia, aggravatingly. "But no woman ever does really think so,

you know. I imagine that pretty Anne Shirley, who is visiting Ella

Kimball, doesn't. I saw her and Dr. Irving out walking this

afternoon, looking very well satisfied with themselves. If you

dilly-dally much longer, Sue, you will let Max slip through your

fingers yet."That

was a tactful thing to say to ME, who had refused Max Irving so

often

that I had lost count. I was furious, and so I smiled most sweetly

on

my maddening aunt."Dear

Aunt, how amusing of you," I said, smoothly. "You talk as

if I wanted Max.""So

you do," said Aunt Cynthia."If

so, why should I have refused him time and again?" I asked,

smilingly. Right well Aunt Cynthia knew I had. Max always told

her."Goodness

alone knows why," said Aunt Cynthia, "but you may do it

once too often and find yourself taken at your word. There is

something very fascinating about this Anne Shirley.""Indeed

there is," I assented. "She has the loveliest eyes I ever

saw. She would be just the wife for Max, and I hope he will marry

her.""Humph,"

said Aunt Cynthia. "Well, I won't entice you into telling any

more fibs. And I didn't drive out here to-day in all this wind to

talk sense into you concerning Max. I'm going to Halifax for two

months and I want you to take charge of Fatima for me, while I am

away.""Fatima!"

I exclaimed."Yes.

I don't dare to trust her with the servants. Mind you always warm

her

milk before you give it to her, and don't on any account let her

run

out of doors."I

looked at Ismay and Ismay looked at me. We knew we were in for it.

To

refuse would mortally offend Aunt Cynthia. Besides, if I betrayed

any

unwillingness, Aunt Cynthia would be sure to put it down to

grumpiness over what she had said about Max, and rub it in for

years.

But I ventured to ask, "What if anything happens to her while

you are away?""It

is to prevent that, I'm leaving her with you," said Aunt

Cynthia. "You simply must not let anything happen to her. It

will do you good to have a little responsibility. And you will have

a

chance to find out what an adorable creature Fatima really is.

Well,

that is all settled. I'll send Fatima out to-morrow.""You

can take care of that horrid Fatima beast yourself," said Ismay,

when the door closed behind Aunt Cynthia. "I won't touch her

with a yard-stick. You had no business to say we'd take

her.""Did

I say we would take her?" I demanded, crossly. "Aunt

Cynthia took our consent for granted. And you know, as well as I

do,

we couldn't have refused. So what is the use of being

grouchy?""If

anything happens to her Aunt Cynthia will hold us responsible,"

said Ismay darkly."Do

you think Anne Shirley is really engaged to Gilbert Blythe?"I

asked curiously."I've

heard that she was," said Ismay, absently. "Does she eat

anything but milk? Will it do to give her mice?""Oh,

I guess so. But do you think Max has really fallen in love with

her?""I

dare say. What a relief it will be for you if he has.""Oh,

of course," I said, frostily. "Anne Shirley or Anne Anybody

Else, is perfectly welcome to Max if she wants him.

I certainly do not.

Ismay Meade, if that stove doesn't stop smoking I shall fly into

bits. This is a detestable day. I hate that creature!""Oh,

you shouldn't talk like that, when you don't even know her,"

protested Ismay. "Every one says Anne Shirley is lovely—""I

was talking about Fatima," I cried in a rage."Oh!"

said Ismay.Ismay

is stupid at times. I thought the way she said "Oh" was

inexcusably stupid.Fatima

arrived the next day. Max brought her out in a covered basket,

lined

with padded crimson satin. Max likes cats and Aunt Cynthia. He

explained how we were to treat Fatima and when Ismay had gone out

of

the room—Ismay always went out of the room when she knew I

particularly wanted her to remain—he proposed to me again. Of

course I said no, as usual, but I was rather pleased. Max had been

proposing to me about every two months for two years. Sometimes, as

in this case, he went three months, and then I always wondered why.

I

concluded that he could not be really interested in Anne Shirley,

and

I was relieved. I didn't want to marry Max but it was pleasant and

convenient to have him around, and we would miss him dreadfully if

any other girl snapped him up. He was so useful and always willing

to

do anything for us—nail a shingle on the roof, drive us to town,

put down carpets—in short, a very present help in all our

troubles.So

I just beamed on him when I said no. Max began counting on his

fingers. When he got as far as eight he shook his head and began

over

again."What

is it?" I asked."I'm

trying to count up how many times I have proposed to you," he

said. "But I can't remember whether I asked you to marry me that

day we dug up the garden or not. If I did it makes—""No,

you didn't," I interrupted."Well,

that makes it eleven," said Max reflectively. "Pretty near

the limit, isn't it? My manly pride will not allow me to propose to

the same girl more than twelve times. So the next time will be the

last, Sue darling.""Oh,"

I said, a trifle flatly. I forgot to resent his calling me darling.

I

wondered if things wouldn't be rather dull when Max gave up

proposing

to me. It was the only excitement I had. But of course it would be

best—and he couldn't go on at it forever, so, by the way of

gracefully dismissing the subject, I asked him what Miss Shirley

was

like."Very

sweet girl," said Max. "You know I always admired those

gray-eyed girls with that splendid Titian hair."I

am dark, with brown eyes. Just then I detested Max. I got up and

said

I was going to get some milk for Fatima.I

found Ismay in a rage in the kitchen. She had been up in the

garret,

and a mouse had run across her foot. Mice always get on Ismay's

nerves."We

need a cat badly enough," she fumed, "but not a useless,

pampered thing, like Fatima. That garret is literally swarming with

mice. You'll not catch me going up there again."Fatima

did not prove such a nuisance as we had feared. Huldah Jane liked

her, and Ismay, in spite of her declaration that she would have

nothing to do with her, looked after her comfort scrupulously. She

even used to get up in the middle of the night and go out to see if

Fatima was warm. Max came in every day and, being around, gave us

good advice.Then

one day, about three weeks after Aunt Cynthia's departure, Fatima

disappeared—just simply disappeared as if she had been dissolved

into thin air. We left her one afternoon, curled up asleep in her

basket by the fire, under Huldah Jane's eye, while we went out to

make a call. When we came home Fatima was gone.Huldah

Jane wept and was as one whom the gods had made mad. She vowed that

she had never let Fatima out of her sight the whole time, save once

for three minutes when she ran up to the garret for some summer

savory. When she came back the kitchen door had blown open and

Fatima

had vanished.Ismay

and I were frantic. We ran about the garden and through the

out-houses, and the woods behind the house, like wild creatures,

calling Fatima, but in vain. Then Ismay sat down on the front

doorsteps and cried."She

has got out and she'll catch her death of cold and AuntCynthia

will never forgive us.""I'm

going for Max," I declared. So I did, through the spruce woods

and over the field as fast as my feet could carry me, thanking my

stars that there was a Max to go to in such a predicament.Max

came over and we had another search, but without result. Days

passed,

but we did not find Fatima. I would certainly have gone crazy had

it

not been for Max. He was worth his weight in gold during the awful

week that followed. We did not dare advertise, lest Aunt Cynthia

should see it; but we inquired far and wide for a white Persian cat

with a blue spot on its tail, and offered a reward for it; but

nobody

had seen it, although people kept coming to the house, night and

day,

with every kind of a cat in baskets, wanting to know if it was the

one we had lost."We

shall never see Fatima again," I said hopelessly to Max and

Ismay one afternoon. I had just turned away an old woman with a

big,

yellow tommy which she insisted must be ours—"cause it kem to

our place, mem, a-yowling fearful, mem, and it don't belong to

nobody

not down Grafton way, mem.""I'm

afraid you won't," said Max. "She must have perished from

exposure long ere this.""Aunt

Cynthia will never forgive us," said Ismay, dismally. "I

had a presentiment of trouble the moment that cat came to this

house."We

had never heard of this presentiment before, but Ismay is good at

having presentiments—after things happen."What

shall we do?" I demanded, helplessly. "Max, can't you find

some way out of this scrape for us?""Advertise

in the Charlottetown papers for a white Persian cat," suggested

Max. "Some one may have one for sale. If so, you must buy it,

and palm it off on your good Aunt as Fatima. She's very

short-sighted, so it will be quite possible.""But

Fatima has a blue spot on her tail," I said."You

must advertise for a cat with a blue spot on its tail,"

saidMax."It

will cost a pretty penny," said Ismay dolefully. "Fatima

was valued at one hundred dollars.""We

must take the money we have been saving for our new furs," I

said sorrowfully. "There is no other way out of it. It will cost

us a good deal more if we lose Aunt Cynthia's favor. She is quite

capable of believing that we have made away with Fatima

deliberately

and with malice aforethought."So

we advertised. Max went to town and had the notice inserted in the

most important daily. We asked any one who had a white Persian cat,

with a blue spot on the tip of its tail, to dispose of, to

communicate with M. I., care of the

Enterprise.We

really did not have much hope that anything would come of it, so we

were surprised and delighted over the letter Max brought home from

town four days later. It was a type-written screed from Halifax

stating that the writer had for sale a white Persian cat answering

to

our description. The price was a hundred and ten dollars, and, if

M.

I. cared to go to Halifax and inspect the animal, it would be found

at 110 Hollis Street, by inquiring for "Persian.""Temper

your joy, my friends," said Ismay, gloomily. "The cat may

not suit. The blue spot may be too big or too small or not in the

right place. I consistently refuse to believe that any good thing

can

come out of this deplorable affair."Just

at this moment there was a knock at the door and I hurried out. The

postmaster's boy was there with a telegram. I tore it open, glanced

at it, and dashed back into the room."What

is it now?" cried Ismay, beholding my face.I

held out the telegram. It was from Aunt Cynthia. She had wired us

to

send Fatima to Halifax by express immediately.For

the first time Max did not seem ready to rush into the breach with

a

suggestion. It was I who spoke first."Max,"

I said, imploringly, "you'll see us through this, won't you?

Neither Ismay nor I can rush off to Halifax at once. You must go

to-morrow morning. Go right to 110 Hollis Street and ask for

'Persian.' If the cat looks enough like Fatima, buy it and take it

to

Aunt Cynthia. If it doesn't—but it must! You'll go, won't

you?""That

depends," said Max.I

stared at him. This was so unlike Max."You

are sending me on a nasty errand," he said, coolly. "How do

I know that Aunt Cynthia will be deceived after all, even if she be

short-sighted. Buying a cat in a joke is a huge risk. And if she

should see through the scheme I shall be in a pretty mess.""Oh,

Max," I said, on the verge of tears."Of

course," said Max, looking meditatively into the fire, "if

I were really one of the family, or had any reasonable prospect of

being so, I would not mind so much. It would be all in the day's

work

then. But as it is—"Ismay

got up and went out of the room."Oh,

Max, please," I said."Will

you marry me, Sue?" demanded Max sternly. "If you will

agree, I'll go to Halifax and beard the lion in his den

unflinchingly. If necessary, I will take a black street cat to Aunt

Cynthia, and swear that it is Fatima. I'll get you out of the

scrape,

if I have to prove that you never had Fatima, that she is safe in

your possession at the present time, and that there never was such

an

animal as Fatima anyhow. I'll do anything, say anything—but it must

be for my future wife.""Will

nothing else content you?" I said helplessly."Nothing."I

thought hard. Of course Max was acting abominably—but—but—he

was really a dear fellow—and this was the twelfth time—and there

was Anne Shirley! I knew in my secret soul that life would be a

dreadfully dismal thing if Max were not around somewhere. Besides,

I

would have married him long ago had not Aunt Cynthia thrown us so

pointedly at each other's heads ever since he came to

Spencervale."Very

well," I said crossly.Max

left for Halifax in the morning. Next day we got a wire saying it

was

all right. The evening of the following day he was back in

Spencervale. Ismay and I put him in a chair and glared at him

impatiently.Max

began to laugh and laughed until he turned blue."I

am glad it is so amusing," said Ismay severely. "If Sue and

I could see the joke it might be more so.""Dear

little girls, have patience with me," implored Max. "If you

knew what it cost me to keep a straight face in Halifax you would

forgive me for breaking out now.""We

forgive you—but for pity's sake tell us all about it," I

cried."Well,

as soon as I arrived in Halifax I hurried to 110 Hollis Street,

but—see here! Didn't you tell me your Aunt's address was 10

Pleasant Street?""So

it is.""'T

isn't. You look at the address on a telegram next time you get one.

She went a week ago to visit another friend who lives at 110

Hollis.""Max!""It's

a fact. I rang the bell, and was just going to ask the maid for

'Persian' when your Aunt Cynthia herself came through the hall and

pounced on me.""'Max,'

she said, 'have you brought Fatima?'"'No,'

I answered, trying to adjust my wits to this new development as she

towed me into the library. 'No, I—I—just came to Halifax on a

little matter of business.'"'Dear

me,' said Aunt Cynthia, crossly, 'I don't know what those girls

mean.

I wired them to send Fatima at once. And she has not come yet and I

am expecting a call every minute from some one who wants to buy

her.'"'Oh!'

I murmured, mining deeper every minute."'Yes,'

went on your aunt, 'there is an advertisement in the

Charlottetown

Enterprise for a

Persian cat, and I answered it. Fatima is really quite a charge,

you

know—and so apt to die and be a dead loss,'—did your aunt mean a

pun, girls?—'and so, although I am considerably attached to her, I

have decided to part with her.'"By

this time I had got my second wind, and I promptly decided that a

judicious mixture of the truth was the thing required."'Well,

of all the curious coincidences,' I exclaimed. 'Why,Miss

Ridley, it was I who advertised for a Persian cat—on Sue'sbehalf.

She and Ismay have decided that they want a cat likeFatima

for themselves.'"You

should have seen how she beamed. She said she knew you always

really

liked cats, only you would never own up to it. We clinched the

dicker

then and there. I passed her over your hundred and ten dollars—she

took the money without turning a hair—and now you are the joint

owners of Fatima. Good luck to your bargain!""Mean

old thing," sniffed Ismay. She meant Aunt Cynthia, and,

remembering our shabby furs, I didn't disagree with her."But

there is no Fatima," I said, dubiously. "How shall we

account for her when Aunt Cynthia comes home?""Well,

your aunt isn't coming home for a month yet. When she comes you

will

have to tell her that the cat—is lost—but you needn't say WHEN it

happened. As for the rest, Fatima is your property now, so Aunt

Cynthia can't grumble. But she will have a poorer opinion than ever

of your fitness to run a house alone."When

Max left I went to the window to watch him down the path. He was

really a handsome fellow, and I was proud of him. At the gate he

turned to wave me good-by, and, as he did, he glanced upward. Even

at

that distance I saw the look of amazement on his face. Then he came

bolting back."Ismay,

the house is on fire!" I shrieked, as I flew to the door."Sue,"

cried Max, "I saw Fatima, or her ghost, at the garret window a

moment ago!""Nonsense!"

I cried. But Ismay was already half way up the stairs and we

followed. Straight to the garret we rushed. There sat Fatima, sleek

and complacent, sunning herself in the window.Max

laughed until the rafters rang."She

can't have been up here all this time," I protested, half

tearfully. "We would have heard her meowing.""But

you didn't," said Max."She

would have died of the cold," declared Ismay."But

she hasn't," said Max."Or

starved," I cried."The

place is alive with mice," said Max. "No, girls, there is

no doubt the cat has been here the whole fortnight. She must have

followed Huldah Jane up here, unobserved, that day. It's a wonder

you

didn't hear her crying—if she did cry. But perhaps she didn't, and,

of course, you sleep downstairs. To think you never thought of

looking here for her!""It

has cost us over a hundred dollars," said Ismay, with a

malevolent glance at the sleek Fatima."It

has cost me more than that," I said, as I turned to the

stairway.Max

held me back for an instant, while Ismay and Fatima pattered

down."Do

you think it has cost too much, Sue?" he whispered.I

looked at him sideways. He was really a dear. Niceness fairly

exhaled

from him."No-o-o,"

I said, "but when we are married you will have to take care of

Fatima, I

won't.""Dear

Fatima," said Max gratefully.

II. THE MATERIALIZING OF CECIL

It had never worried me in the least that I wasn't married,

although everybody in Avonlea pitied old maids; but it DID worry

me, and I frankly confess it, that I had never had a chance to be.

Even Nancy, my old nurse and servant, knew that, and pitied me for

it. Nancy is an old maid herself, but she has had two proposals.

She did not accept either of them because one was a widower with

seven children, and the other a very shiftless, good-for-nothing

fellow; but, if anybody twitted Nancy on her single condition, she

could point triumphantly to those two as evidence that "she could

an she would." If I had not lived all my life in Avonlea I might

have had the benefit of the doubt; but I had, and everybody knew

everything about me—or thought they did.

I had really often wondered

why nobody had ever fallen in love with me. I was not at all

homely; indeed, years ago, George Adoniram Maybrick had written a

poem addressed to me, in which he praised my beauty quite

extravagantly; that didn't mean anything because George Adoniram

wrote poetry to all the good-looking girls and never went with

anybody but Flora King, who was cross-eyed and red-haired, but it

proves that it was not my appearance that put me out of the

running. Neither was it the fact that I wrote poetry

myself—although not of George Adoniram's kind—because nobody ever

knew that. When I felt it coming on I shut myself up in my room and

wrote it out in a little blank book I kept locked up. It is nearly

full now, because I have been writing poetry all my life. It is the

only thing I have ever been able to keep a secret from Nancy.

Nancy, in any case, has not a very high opinion of my ability to

take care of myself; but I tremble to imagine what she would think

if she ever found out about that little book. I am convinced she

would send for the doctor post-haste and insist on mustard plasters

while waiting for him.

Nevertheless, I kept on at

it, and what with my flowers and my cats and my magazines and my

little book, I was really very happy and contented. But it DID

sting that Adella Gilbert, across the road, who has a drunken

husband, should pity "poor Charlotte" because nobody had ever

wanted her. Poor Charlotte indeed! If I had thrown myself at a

man's head the way Adella Gilbert did at—but there, there, I must

refrain from such thoughts. I must not be uncharitable.

The Sewing Circle met at

Mary Gillespie's on my fortieth birthday. I have given up talking

about my birthdays, although that little scheme is not much good in

Avonlea where everybody knows your age—or if they make a mistake it

is never on the side of youth. But Nancy, who grew accustomed to

celebrating my birthdays when I was a little girl, never gets over

the habit, and I don't try to cure her, because, after all, it's

nice to have some one make a fuss over you. She brought me up my

breakfast before I got up out of bed—a concession to my laziness

that Nancy would scorn to make on any other day of the year. She

had cooked everything I like best, and had decorated the tray with

roses from the garden and ferns from the woods behind the house. I

enjoyed every bit of that breakfast, and then I got up and dressed,

putting on my second best muslin gown. I would have put on my

really best if I had not had the fear of Nancy before my eyes; but

I knew she would never condone THAT, even on a birthday. I watered

my flowers and fed my cats, and then I locked myself up and wrote a

poem on June. I had given up writing birthday odes after I was

thirty.

In the afternoon I went to

the Sewing Circle. When I was ready for it I looked in my glass and

wondered if I could really be forty. I was quite sure I didn't look

it. My hair was brown and wavy, my cheeks were pink, and the lines

could hardly be seen at all, though possibly that was because of

the dim light. I always have my mirror hung in the darkest corner

of my room. Nancy cannot imagine why. I know the lines are there,

of course; but when they don't show very plain I forget that they

are there.

We had a large Sewing

Circle, young and old alike attending. I really cannot say I ever

enjoyed the meetings—at least not up to that time—although I went

religiously because I thought it my duty to go. The married women

talked so much of their husbands and children, and of course I had

to be quiet on those topics; and the young girls talked in corner

groups about their beaux, and stopped it when I joined them, as if

they felt sure that an old maid who had never had a beau couldn't

understand at all. As for the other old maids, they talked gossip

about every one, and I did not like that either. I knew the minute

my back was turned they would fasten into me and hint that I used

hair-dye and declare it was perfectly ridiculous for a woman of

FIFTY to wear a pink muslin dress with lace-trimmed

frills.

There was a full attendance

that day, for we were getting ready for a sale of fancy work in aid

of parsonage repairs. The young girls were merrier and noisier than

usual. Wilhelmina Mercer was there, and she kept them going. The

Mercers were quite new to Avonlea, having come here only two months

previously.

I was sitting by the window

and Wilhelmina Mercer, Maggie Henderson, Susette Cross and Georgie

Hall were in a little group just before me. I wasn't listening to

their chatter at all, but presently Georgie exclaimed

teasingly:

"Miss Charlotte is laughing

at us. I suppose she thinks we are awfully silly to be talking

about beaux."

The truth was that I was

simply smiling over some very pretty thoughts that had come to me

about the roses which were climbing over Mary Gillespie's sill. I

meant to inscribe them in the little blank book when I went home.

Georgie's speech brought me back to harsh realities with a jolt. It

hurt me, as such speeches always did.

"Didn't you ever have a

beau, Miss Holmes?" said Wilhelmina laughingly.

Just as it happened, a

silence had fallen over the room for a moment, and everybody in it

heard Wilhelmina's question.

I really do not know what

got into me and possessed me. I have never been able to account for

what I said and did, because I am naturally a truthful person and

hate all deceit. It seemed to me that I simply could not say "No"

to Wilhelmina before that whole roomful of women. It was TOO

humiliating. I suppose all the prickles and stings and slurs I had

endured for fifteen years on account of never having had a lover

had what the new doctor calls "a cumulative effect" and came to a

head then and there.

"Yes, I had one once, my

dear," I said calmly.

For once in my life I made a

sensation. Every woman in that room stopped sewing and stared at

me. Most of them, I saw, didn't believe me, but Wilhelmina did. Her

pretty face lighted up with interest.

"Oh, won't you tell us about

him, Miss Holmes?" she coaxed, "and why didn't you marry

him?"

"That is right, Miss

Mercer," said Josephine Cameron, with a nasty little laugh. "Make

her tell. We're all interested. It's news to us that Charlotte ever

had a beau."

If Josephine had not said

that, I might not have gone on. But she did say it, and, moreover,

I caught Mary Gillespie and Adella Gilbert exchanging significant

smiles. That settled it, and made me quite reckless. "In for a

penny, in for a pound," thought I, and I said with a pensive

smile:

"Nobody here knew anything

about him, and it was all long, long ago."

"What was his name?" asked

Wilhelmina.

"Cecil Fenwick," I answered

promptly. Cecil had always been my favorite name for a man; it

figured quite frequently in the blank book. As for the Fenwick part

of it, I had a bit of newspaper in my hand, measuring a hem, with

"Try Fenwick's Porous Plasters" printed across it, and I simply

joined the two in sudden and irrevocable matrimony.

"Where did you meet him?"

asked Georgie.

I hastily reviewed my past.

There was only one place to locate Cecil Fenwick. The only time I

had ever been far enough away from Avonlea in my life was when I

was eighteen and had gone to visit an aunt in New

Brunswick.

"In Blakely, New Brunswick,"

I said, almost believing that I had when I saw how [...]