6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

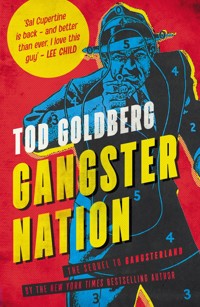

September 2001: two years since legendary Chicago hitman Sal Cupertine disappeared into the guise of Las Vegas Rabbi David Cohen. For David, everything is coming up gold: temple membership is on the rise, the new school is raking it in, and the mortuary and cemetery, where he launders bodies for the mob, is minting cash. But Sal wants out. He's got money stashed all over the city. If he makes it through Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, he'll have enough to slip away, grab his wife and kid and start afresh. Across the country, former FBI agent Matthew Drew is now running security for a casino outside of Milwaukee, spending his time off stalking members of The Family, looking to avenge his former partner's murder. So when Sal's cousin stumbles into the casino, Matthew takes the law into his own hands, starting a chain of events that will have Rabbi Cohen running for his life, trapped in Las Vegas, with the law, society, and the post-9/11 world closing in on him. Gangster Nation is a page-turning examination of the seedy foundations of American life. With the wit and gritty glamour that defines his writing, Goldberg traces how the things we value most in our lives - home, health, even our spirituality - have been built on the enterprises of criminals.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

GANGSTER NATION

It’s been two years since legendary Chicago hitman Sal Cupertine disappeared into the guise of Las Vegas Rabbi David Cohen. It’s September 2001 and for David, everything is coming up gold: temple membership is on the rise, the new private school is raking it in, and the mortuary and cemetery, where Cohen has been laundering bodies for the mob, is minting cash. But Sal wants out. He’s got money stashed in safe-deposit boxes all over the city. He’s looking at places to escape to, Mexico or maybe Argentina. He only needs to make it through Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur and he’ll have enough money to slip away, grab his wife and kid and start fresh.

Across the country, former FBI agent Matthew Drew is now running security for a casino outside of Milwaukee, spending his off-time stalking members of The Family, looking for vengeance for the murder of his former partner. So when Sal’s cousin stumbles into the casino one night, Matthew takes the law into his own hands, starting a chain of events that will have Rabbi Cohen running for his life, trapped in Las Vegas, with the law, society, and the post-9/11 world closing in on him.

Gangster Nation is a page-turning examination of the seedy foundations of American life. With the wit and gritty glamour that defines his writing, Goldberg traces how the things we value most in our lives – home, health, even our spiritual lives – have been built on the enterprises of criminals.

About the author

Tod Goldberg is the author of more than a dozen books, including Gangsterland, a finalist for the Hammett Prize; The House of Secrets, which he co-authored with Brad Meltzer; and the crime- tinged novels Living Dead Girl, a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and Fake Liar Cheat, plus five novels in the popular Burn Notice series. He is also the author of the story collection Simplify, a 2006 finalist for the SCIBA Award for Fiction and winner of the Other Voices Short Story Collection Prize, and Other Resort Cities. His essays, journalism, and criticism have appeared in many publications, including the Los Angeles Times, The Wall Street Journal, Los Angeles Review of Books, Las Vegas Weekly, and Best American Essays, and have won five Nevada Press Association Awards. He lives in Indio, California, where he directs the Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing & Writing for the Performing Arts at the University of California, Riverside.

todgoldberg.com

PRAISE FOR GANGSTERLAND

‘Inhisplotting,dialogue,andempathyforthebadguys,Goldbergaspirestothe heights of Elmore Leonard. For those who miss the master, Gangsterland is a high-gradesubstitute’ – The NewYork Times

‘Formanyofus,TheGodfather,bookormovie,usheredusintoasecondboyhood, teaching that the incorrigible vitality of a first-rate gangster story could temporarilyinoculateusagainstadultsanity.Forreadersofalikemind,TodGoldberg’s Gangsterland will arrive as a gloriously original Mafia novel: 100 percent unhinged about the professionally unhinged… Torridly funny… The novel swellswithaspiritualbutjazzytone’ – TheNewYorkTimesBookReview

‘Gangsterlandexploresthequestion:Whatwouldhappenifahitmanwereforced tofakebeingreligious?… ThatledtothenuancesofGangsterland – tonotonly become a page turner, but also to expand beyond that… into an environment of faithandspirituality’ – San FranciscoChronicle

‘Thesetupisblacklycomic,theplottingatadrococo,thepayoffgrimbutsly…Goldberg’snewbookiscleverborderingonwise,likeGetShortyonantacid’ – David Kipen, Los Angeles Magazine

‘As sharp as a straight razor. But a lot more fun. Count me a huge fan’ – Lee Child, New York Times bestselling author of Personal: A Jack Reacher Novel

‘Gangsterlandisrichwithcomplexandmeatycharacters,butitsgreateststrength is that it never pulls a punch, never holds back, and never apologizes for life’s absurdities.Ifthisnovelwereaperson,youcouldaskitforabookie’ – Brad Meltzer, bestselling author of The Fifth Assassin

‘Complex characters with understandable motivations distinguish this highly unusual crime novel… Goldberg injects Talmudic wisdom and a hint of Springsteen into the workings of organized crime and FBI investigative techniques and makes it all work splendidly’ – Publishers Weekly (starred review)

‘Sal’s transformation – and intermittent edification – into Rabbi Cohen is brilliantlyrendered,andGoldberg’scareeningplot,castofmemorablydubiouscharacters, and mordant portrait of Las Vegas make this one of the year’s best hard-boiledcrimenovels’ – Booklist (starredreview)

‘Clever plotting, a colorful cast of characters, and priceless situations make this comedic crime novel an instant classic’ – Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

‘Unlike many of his literary forebears and contemporaries, Goldberg, it seems, has not been seized by self-evisceration or self-doubt. There’s no scolding messaging about universalism here, just respect for a group that looks after its own… As Rabbi Cohen observes, who wants to hear the same old stories? For thosewhodon’t,thereisGangsterland’ – LosAngelesReviewofBooks

‘Notintogangstercapers?TheskillfullyspunGangsterlandcouldconvertyou… A cleverly spun novel that forced me to abandon my wiseguy moratorium. Goldberg has an amusing flair for contemporary hard-boil, and he knows his crime andcrime-fightingprocedures’ – Las VegasWeekly

‘Tod Goldberg’s wickedly dark and hilarious new book will remind you of everything you love about Walter White (or any Coen brothers antihero, for thatmatter)’ – Purewow

‘The Mafia plus the Torah makes for a darkly funny and suspenseful morality tale… The man can spin agood yarn’ – EdanLepucki,TheMillions

‘This tale of witness relocation-by-mob – part Elmore Leonard, part Theatre of the Absurd – is a compelling examination of salvation, which comes in various guises and moves in elusive ways. A wholly unique tale from a wholly unique voice’– GreggHurwitz,NewYorkTimesbestsellingauthorofDon’tLookBack

‘Tod Goldberg is a one-of-a-kind writer, and this is his best novel to date. Harrowing, funny, wise, and heretical, Gangsterland is everything a thriller should be’ – T JeffersonParker,authorofFullMeasure

For Wendy, who makes me a better man

Whoever destroys a soul, it is considered as if he destroyed an entire world. And whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world.

– the talmud

PROLOGUE

November 2000

Peaches Pocotillo never got to kill anyone anymore. All those years he’d spent perfecting his craft had led to bigger and better things, which in this case meant a mid-level leadership position in the Native Mob, overseeing tribal gang consolidation and farming operations in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Illinois, even into Nebraska. He had Native Gangster Disciples reporting to him, Native Vice Lords, Native Crips, Native Bloods, Peaches the one guy everyone listened to, the one guy who could get everyone to the table, the one guy who you didn’t want to cross, because, man, he used to kill people for nothing, son.

That reputation got him in the room. Still had to make the sale. But he was good at that, too.

So he was the guy they’d send to sit down with some Native Crip shot caller to explain, patiently, why co-opting the iconography of a Los Angeles gang that would kill him on sight was bad business. It put everyone in jeopardy. So, sure, call yourself a Crip while you’re out tending the dirt fields in Nebraska. But you come to Minneapolis, Green Bay, or Chicago? You either called yourself Native Mob or you called yourself dead. Then he’d paint a more optimistic picture: See all this reservation farmland? See all those beets? See all that kale? Shit no one likes to eat. Imagine it green with marijuana. Don’t worry, we gotthe recipe. Don’t worry, we’ll front you the cost of machinery. Don’t worry, we got the protection. Don’t worry, we got distribution.

That advice? That’s fifty thousand dollars. Big bills are fine. By tomorrow. Next day? It’s seventy-five. End of the week? Don’t worry, we’ll give your mom something to help her with the bills.

Now, three in the morning, crossing over the Blackburn Point Bridge from Osprey, Florida, onto Casey Key, sitting in the passenger seat of a rented Ford Taurus – big trunk but it handled like a rhino, American cars absolute crap these days – Peaches could see his middle management career coming to an end. His own thing on the horizon. He was forty-five years old. The time for waiting was over.

His nephew Mike, who he liked but didn’t think was exceptionally bright, pulled up in front of the Pirate’s Cove Apartments and cut the engine. The Pirate’s Cove consisted of six low-slung white bungalows surrounded by stumpy palm trees and beds of hibiscus that had begun to grow wild, climbing up toward the blue Bermuda shutters that were pushed out, letting in the gulf breeze. It had been hot and humid all day. Mike’s Midwest blood was not suited to this Florida bullshit, even this late in the year, but Peaches liked it, particularly now that it was in the sixties and the air finally thin enough to breathe.

‘Uncle,’ Mike said, ‘this place is nice.’

It was. Or, well, the land was. The Pirate’s Cove was a dump but it was surrounded on either side by mansions – only a few hundred yards east of the Gulf of Mexico, a few hundred yards west of the Intracoastal Waterway. Prime real estate. Worth maybe a million, a million and a half. Even more if the bungalows were torn down. Peaches knew about real estate, had made it his specialty, had his broker’s license, was happy to sift through public records, knock on doors, talk about gentrification, talk about curb appeal, talk about market value, talk about how, for his tribe the Chuyalla, real estate was the ticket to prosperity. That if they wanted to move real weight, they had to take their casino profits and roll that into durable investments, which sometimes meant buying up land that had once been theirs in the first place.

Lately, though, he’d been all about buying up commercial space, medical buildings, but especially any empty plots next to phone company switching stations, particularly in shitty little towns, Peaches thinking ahead, seeing how the internet was changing business. Phone companies were going to need that space. Build server farms. Data was a more durable crop than weed, but that wasn’t something Peaches was confident his soldiers could cultivate. So he knew something about how to improve investments and he knew no one had bothered to update these bungalows since 1953, which is when Ronnie Cupertine’s father, Tom ‘Dandy Tommy’ Cupertine, bought the land in the first place.

Almost fifty years later, the Pirate’s Cove was in the name of an LLC and was operated by a property management company in Chicago. In all that time, though, the property had never been sold. Peaches stumbled on it while searching the records for every bit of residential property in the Cupertine family name, going all the way back to the early 1900s, looking for plausible safe houses for the Family, as far away from Chicago as possible. The Pirate’s Cove had been quit-claimed thirteen times up through the 1980s, but since then, nothing. It took Peaches about three months to plow through microfiche and old deeds and records, since he had to do it all by hand, couldn’t get some file clerk on the Family payroll interested in what he was looking for, not that anyone in Osprey looked particularly mobbed up.

Next, Peaches rented a house up the block from the Pirate’s Cove and spent a month walking up and down the beach, making friends. Started wearing linen, started to take to it, actually. Bought tortoiseshell glasses. Played the part. Sat out on the beach in front of the Pirate’s Cove a couple nights a week, chatted up the tenants coming in and out, found out Terrance worked the line at Casey Key Fish House, also dealt a little coke, neighbors showing up on Friday nights in their Audis and BMWs, Peaches picking up a few lines, too, for Halloween. It was crap. Baking soda and Adderall. The kind of shit that would get you killed in the real world. Out here, they were just happy for the bump. Sandi and Lisa, they were Jet Ski instructors at the Gulf Resort and Spa. Rob was the bartender at the Beachcomber, nice place if you liked tiki bars. Pasqual was teaching at a private school in Sarasota, just lucked into a spot on the water. Becca and Tony were servers at the Charthouse. Frank and Doreen, they were the on-site managers. Married couple. Super nice, everyone said so.

Frank and Doreen, they didn’t get any mail.

Frank and Doreen, they didn’t have any friends. No kids. Not even a cat.

Frank and Doreen, they didn’t talk too much, had Chicago accents so thick it was like sitting in the bleachers at Wrigley.

‘Two minutes,’ Peaches said. ‘Three at the most.’

Mike rolled down his window. Sniffed. ‘It’s so wet out here, Uncle, I’m gonna have to double up.’

Back in the day, Peaches worked alone. But this was a two-man job, and Mike had shown himself to be pretty good with accelerants. He didn’t know why Mike needed to sniff to figure out the wetness in the air, but whatever. Everyone had their moves.

‘Do what you need to do.’ Peaches reached into the backseat, unzipped his travel bag, took out a steel-headed drilling hammer. He didn’t have any guns with him, because he’d be tempted to use them, and this wasn’t the type of neighborhood where people would sleep through a gunshot.

Frank Fishmann had been driving a truck for Kochel Farms for twenty-five years, so his back was fucked up, his knees were shit, his night vision was half gone. He was fifty-five, about thirty pounds overweight, and he hadn’t been bright enough to decline the job of hustling the Rain Man out of town in the back of his refrigerated meat truck. Well, Peaches considered, maybe that wasn’t exactly true. He probably didn’t have a choice. Frank was bright enough not to come forward to the FBI with information on where he’d dumped Sal Cupertine, even though that information was worth a $500,000 reward. Instead, he’d spent the last two years hiding out on Ronnie Cupertine’s dime. The one guy still alive, other than Ronnie, who knew where Sal Cupertine might be living was spending his days on the edge of the continent, ocean view. Probably the best years of his life.

Mike popped the trunk, came out with three gas cans, headed into the darkness. He’d set the fires on their way out, if Peaches thought they needed the cover, or in case things got messy. Peaches walked over to Frank and Doreen’s bungalow, the one closest to the street, the stench of gasoline already starting to waft toward him, pounded on the door, waited, pounded again. A light came on.

If Doreen answered, that would be too bad.

A shadow crossed the peephole. Peaches raised his left hand and waved, gave a faint smile. ‘It’s me,’ Peaches said. ‘So sorry to bother you in the middle of the night.’ Whoever was on the other side of the peephole took another few seconds, probably contemplating the risk. If this were Chicago, a bullet would already be through the peephole and out the back of their head. ‘So sorry,’ Peaches said again. ‘Frank? Is that you? It’s me. Mr Taylor.’ That’s what Frank knew him as. The neighbor up the way. A real nice guy.

The porch light came on and Frank opened the door, stepped onto his small front porch, closed the door behind him. Had on a pair of pajama bottoms, no shirt. A tattoo of an eagle on his chest. That was unexpected. ‘What’s going on, Mr Taylor?’ he began to say, honest concern in his voice, but before he could get it all out, Peaches hit him flush on the right temple with the hammer, caving in the side of his head with a single blow. Maybe breaking his neck, too, judging by the way Frank went to the ground, his body kinked into an S.

Peaches hit him three more times, regardless, stopping only when he saw brain matter.

Frank Fishmann’s whole life ended in three seconds. Maybe fewer. That’s all it took, if you knew what you were doing.

Mike appeared out of the shadows and they picked up Frank, carried him to the Taurus, dropped him in the trunk, closed it. Looked around.

Nothing.

Peaches checked his watch. Three minutes, start to finish. Almost exactly.

‘All right,’ he said, more to himself, really. ‘All right.’ He could still do it. He wasn’t just about the business. That was good to know.

‘We good?’ Mike asked.

They’d left a fair amount of blood and hair and viscera on the porch, but once Doreen realized Frank was gone, what was she gonna do? She was a felon, at this point, even if she wasn’t before. She could call Ronnie, but Peaches didn’t imagine she knew his number. Or his name. Probably had no idea of anything, if Frank was any kind of decent. She couldn’t go back to Chicago, that was for sure. Best thing for her, really, was to pretend nothing happened. Live her life. Hose off the porch.

‘What’s the word, Uncle?’

Peaches loved Mike. He did. Twenty-two. His little sister’s kid.

But still.

This is why Peaches usually preferred to work alone. If he didn’t want to worry about Mike flipping on him one day, Mike had to have his own crime tonight, something bigger than an accessory beef, which the government didn’t mind turning their heads on. So Mike had to have it worse. Burn half a dozen people to death while they slept? You didn’t plead down on that charge, no matter what you gave up.

‘Light it up,’ Peaches said.

Two days later, back in Chicago, Peaches went through an OG in the Gangster 2-6 – the Mexican gang the Family used to move drugs – to make the meeting happen. Lonzo Guijarro middled heroin and meth out to the hinterlands, so he and Peaches had done a few deals over the last couple years. Fair prices, no drama, Peaches able to get some good shit for the tribes, Lonzo getting credit for opening up a new market, everyone square.

Even with that shared past, Peaches still had to deliver ten Gs in a Trader Joe’s shopping bag to Lonzo that morning, the two of them meeting at the Diner Grill in Lakeview, where Lonzo liked to eat breakfast. Peaches set the bag between them on the counter like it was filled with organic bananas and locally sourced honey.

‘This is nonrefundable,’ Lonzo told him. He didn’t even bother to look inside or count the money. ‘If the boss doesn’t like the way you walk or thinks you got bad breath or some shit, that’s not my problem. You cool with that?’

‘I’m not a complainer, Lonzo,’ Peaches said. ‘Mr Cupertine doesn’t take to me, that’s fine. We don’t need to be friends. You and me, we don’t need to be friends either.’

Lonzo shifted on his stool. The Diner Grill was an old railroad dining car, so it was just twelve stools up against a Formica counter, one guy working the grill, another guy taking orders, both dressed in white shirts, white soda jerk hats, everyone overhearing everyone, if anyone bothered to listen. ‘All’s I’m saying,’ Lonzo said, ‘is that the boss is keeping it low. You feel me?’

Peaches couldn’t say he blamed him. Ronnie had spent the better part of the last year trying to unfuck himself after the Chicago Tribune detailed widespread corruption within the Chicago FBI’s Organized Crime Task Force, eventually tying Sal Cupertine’s murder of three undercover FBI agents and a CI at the Parker House to a series of gangland and jailhouse killings of Family and Gangster 2-6 soldiers and associates, and then what appeared to be some modicum of complicity with the FBI, suggesting that a network of high-level snitches were working both sides of the aisle, culminating in the faked death of Sal Cupertine. The Family had Sal shipped out of town in a refrigerated meat truck – the one driven by Frank Fishmann – and then dumped a couple of their soldiers’ bodies in the Poyter Landfill, along with Sal’s ID, and everyone played nice, acted like Sal Cupertine was dead, case closed. It all fell apart courtesy of a tip from a former FBI agent named Jeff Hopper, who conveniently disappeared, too, until his severed head showed up in a dumpster in Chicago a few weeks after the first stories hit.

Peaches read about it just like the rest of the city did, except he saw a crack opening. So when the DOJ ended up cleaning house locally, putting on some show trials down in Springfield, then rousting half of the Family on a variety of charges, hollowing out the organization of the real earners, low-level guys copping to every crime they could, Peaches made note. The middle management was loyal, willing to save their boss from prison, probably for a little something when they got out. Do a couple years in Stateville or Joliet, come out, get a bar or a restaurant in Elmhurst? Easy. But it also meant Ronnie Cupertine was going to have a vacuum in the middle of his organization.

Because in the end, the feds never did find Sal Cupertine, and they never did find the last person to see him alive, either, so they had dick on Ronnie Cupertine himself.

Lonzo pointed out the window. ‘That your guy in the Lincoln?’

Mike was idling in a blue zone out front. ‘My nephew.’

‘That’s a five-hundred-dollar ticket, parking there,’ Lonzo said.

‘He has a handicapped placard,’ Peaches said. It was impossible to park in Chicago, and Peaches wasn’t going to be one of those assholes who got shot walking to his car in some dark parking structure. Handicapped parking was always well lit, always close to the door.

Lonzo raised his eyebrows. ‘No shit? I’ll have to look into that.’ He reached into the Trader Joe’s bag, came out with two twenties, dropped them on his plate, then pointed out the diner’s window. ‘Get what you need from your car and then tell your guy you’re riding with me. He can go park somewhere, read a book or something. Leave the space for someone with a real problem.’

‘That’s not how I work,’ Peaches said.

‘Wasn’t a request,’ Lonzo said.

Lonzo wasn’t a guy who got off making threats. Peaches looked down the counter. There were two uniformed cops sitting at the far end, staring straight ahead, drinking coffee, eating toast. An old lady, oxygen tank at her feet. A black guy sitting with a white girl, eating off each other’s plate. Two older men in suits, sipping coffee, reading the paper, not a fistfight between them.

When he looked back at the cops, they were both staring at him with notably blank expressions.

Okay.

‘Expensive help,’ Peaches said.

Lonzo downed the rest of his coffee, slid off his stool. ‘You in it now for real.’

Two patrol cars followed behind Lonzo’s red Escalade all the way until he parked in front of a house on West Junior Terrace, a street lined with old growth buckthorn and two- and three-story homes, a few blocks from Montrose Beach. Peaches was familiar with the properties here, at least on paper. They’d been in the Cupertine family for decades. Three houses on one side of the street, two on the other, another down the block. Sometimes there were families living in them. Sometimes there were girlfriends. Sometimes they were just empty. They weren’t safe houses, not in this neighborhood, where the average home price was getting close to a million five. They weren’t places where people were getting done dirty, either, since every house on the block had security cameras and their own private security patrols, Peaches not really sure who the neighbors thought was gonna walk up on them here… though, fact was, there were two bad guys parked on the street right now.

Peaches started to get out, but Lonzo said, ‘Hold up.’

One of the cruisers double-parked down the block, on the corner of North Clarendon. Peaches looked over his shoulder, saw the other cruiser parked on the corner of Hazel, boxing the block in.

‘You always roll with cops?’ Peaches asked.

‘Only on Family business,’ he said. ‘Hard to get used to it at first, but fuck it. It is what it is.’ Lonzo pointed at the house in front of them. ‘Go on in. Ronnie’s guys are a little much, but he’s cool. Like talking to a congressman. Friendly but about that business.’

‘You talk to a lot of congressmen?’

‘You’d be surprised,’ Lonzo said. Peaches retrieved his briefcase from the backseat. It was filled with cash. The cost of doing business with Ronnie Cupertine was you had to pay for his time. Lonzo had already looked inside it, felt around, made sure Peaches wasn’t trying to smuggle in a hand grenade. Though he did have a little something extra for Ronnie Cupertine under all the cash. ‘Last thing,’ Lonzo said. ‘You come out and I’m gone for some reason? That’s bad news. Those cops? They’re here to protect the boss. Not you.’

‘I get it,’ Peaches said, knowing it wouldn’t always be like that.

After he frisked him, a beefy guy calling himself Donte, wearing a Kevlar vest under his suit, guided Peaches downstairs into a finished basement, which connected to another finished basement through a long, narrow hallway. Okay, Peaches thought. I’m next door. But then they went through two more corridors, these ones crooked, Peaches’s sense of direction getting fucked up after about two minutes of winding around. Peaches thought he was across the street now, or maybe right back where he started. They ended up in another corridor that fed into yet another basement, and this one looked like a fairly decent rumpus room from the 1970s: shag carpet, wood paneling, a leather recliner, L-shaped sofa, dartboard, wet bar. Ronnie Cupertine shooting pool by himself.

‘You can leave us alone,’ Ronnie said to Donte, though Peaches didn’t think they were alone, since he saw that there were cameras mounted on all four walls. This guy was more paranoid than Nixon. ‘You play?’ Ronnie asked once his guy left.

‘No,’ Peaches said.

‘No one does anymore,’ he said. He lined up his shot – the six in the corner – and hit it, missed wide to the left, though he did manage to sink his cue ball. ‘Shit.’ Ronnie stood up straight, cracked his neck. ‘Problem with no one wanting to play with me is it’s easier for me to cheat.’ He walked to the other side of the table, dug out his cue ball, and rolled the six into a pocket, too. He set his stick across the table. ‘So, who the fuck are you?’

‘I’m here representing the Native Mob,’ Peaches said, which Ronnie knew. Peaches figured he had to peacock a bit, put on his show, be about that business after he figured out a few things. Ronnie wasn’t the boss of bosses, but he ran Chicago, and for that alone, Peaches had admiration for him. He’d been at the tip of the spear since 1972, though one Cupertine or another ran the game since forever. Peaches had been hearing about Ronnie Cupertine his entire life. Plus the commercials for his car lots ran on every TV and radio.

‘I always wanted to ask,’ Ronnie said, ‘do you call yourselves the Native Mob? Or someone else call you that?’

‘We chose it,’ Peaches said, though he didn’t actually know if that was true.

‘The Family,’ Ronnie said. ‘The Outfit. Not a lot of nuance there, but enough to hide behind on a tape. Anyone can be a family or working for an outfit. It’s just funny to me, how you guys start calling yourself the Mob, spray-painting it on billboards, screaming it before you shoot somebody. Seems a tad obvious, no?’

‘No more obvious than a man in a suit wearing Kevlar,’ Peaches said.

‘Maybe so,’ Ronnie said. He walked over to the bar, poured himself a scotch. ‘You drink?’

‘Not when I’m working,’ Peaches said. He didn’t ever drink. He liked to take some pills. An Oxy every now and then. Made shit smoothed out. A little weed. Coke to fit in, if need be.

‘Who’s that guy keeps getting arrested?’ Ronnie said. ‘In Michigan? Indian with an Irish name? Collins?’

The Native Mob wasn’t run like the Family, with one guy at the top. Instead, it had a council, decisions made democratically, things like drug profits getting split up evenly. When casinos and bingo rooms were involved, however, it got more complex; no one wanted to share anything. Richard Collins was part of the tribe opening casinos in Michigan, from Acme to Williamsburg. Doing it right. Spas and condos. High end. Problem was that he was also moving weight out of Canada. Landed a private plane filled with cocaine on reservation land. Now Michigan was dead, Native Mob telling everyone to stick to their places, don’t come up there, let shit cool down. Peaches had other plans.

‘He’s not involved in this,’ Peaches said.

‘You guys need better lawyers,’ Ronnie said. ‘Been getting fucked by the government for a long time now.’

‘I’ll mention that to my boss.’

‘Your boss know you’re here?’

‘Your boss know I’m here?’ Peaches said. He pointed at the cameras. ‘Or is that the feds on the other side?’

‘That’s funny,’ Ronnie said. Not that he laughed. ‘You come here to make jokes?’

‘I wasn’t making a joke,’ Peaches said. ‘I just know you’ve been lucky with the government and so I wondered why. Then I saw those cameras and thought maybe I was in an interrogation room.’

‘You think I answer to anybody?’ Ronnie swirled the ice around in his drink, took a drink. Sniffed. ‘You wearing perfume?’

‘I think you’re worried that you’ll have to,’ Peaches said, ignoring the second question, ‘or else you wouldn’t put cameras in your own home.’

‘I don’t live here,’ Ronnie said. ‘But your auntie? In Green Bay? I say the word, she’s living underneath floorboards here by the end of the day. Your cousin right next to her. But personally? I’m not worried about anything.’ He took another sip. ‘You done measuring your dick in front of me, son?’

All right.

Everybody knows everybody.

That was fast.

‘I’m not trying to insult you, Mr Cupertine,’ Peaches said. ‘You’re getting the wrong impression.’ He walked over to the wet bar, looked up at the camera mounted above it. State of the art for about 1985. These fucking people. All their operations were antiquated. ‘If you’ve got someone on the other side of this camera? You answer to them. That’s just a fact, Mr Cupertine. I’m just pointing out a logistical concern you should have. Problem happens? You’re down here, they’re up there. You’re dead already, yeah? What’s the big deal if they witness the crime but can’t stop it?’

‘Who’s to say you’d make it out alive?’

‘Nobody,’ Peaches said. ‘I wouldn’t expect to. But also? I don’t give a fuck what you do to my auntie. I don’t give a fuck what you do to my cousin, either. Kill them both right now. You and me, we still have business.’ He went over to the sofa, lifted up one of the cushions. There was a pull-out bed inside. Man. If it was up to Peaches, he’d fill this basement with cement, all the way to the roof. Science left these people behind. ‘I see things differently, Mr Cupertine, and that can work to your advantage.’

‘Why don’t you open that briefcase,’ Ronnie said.

Peaches came back to the pool table, popped open the case, set it on the green felt. He had fifty thousand in used twenties, so it was going to take a minute to unpack. ‘Case in point, Mr Cupertine? I know you’re not gonna go kill my auntie, because that’s not how the Family operates. You don’t kill families. So before you stand here and threaten me with it, you gotta do it sometimes to make it plausible. Not farm that shit out, either. Actually send a couple fucking Italians out there to kill an old lady.’ He started to put the cash down, one stack at a time, fifty in total. ‘This place you got here? Don’t get me wrong. It’s peaceful. But this carpet contains the DNA of every person who has stepped foot in here. Same with that sofa and that recliner. The grout in your wood paneling is rubber, which means any bit of hair or skin floating around in the dust is stuck in it. Blood, spit, snot, same deal. You could set fire to this place, cops could probably still dig hair and fiber out of the walls.’ He ran a hand across the top of the pool table. ‘This felt is a problem, too. You may as well cover it with mugshots.’ He put the last of the cash down and then took out two padded mailers that were on the bottom of the case.

Ronnie took a sip from his drink. ‘Aren’t you a smart mother-fucker,’ he said after a while.

‘I’m trying to be,’ Peaches said.

‘What is it you’re interested in?’

‘You need partners,’ Peaches said. ‘Your best guys are in prison, or they’re missing, or they’re dead. Gangster 2-6, they’re going to run out the door soon as the Cartels make them a decent offer, particularly now that they know you dumped one of theirs in a garbage pit trying to deke out the feds. I respect the game, but those Mexicans? They don’t give a fuck about you. They just want your product. The Cartels can get them all the weed and coke they want and they don’t need to go through you.’

‘They don’t have access to heroin,’ Ronnie said. ‘Not like I do.’

‘Not yet,’ Peaches said. ‘You get that good stuff, I agree. Afghanistan and shit. It’s nice. But people, they don’t need the good stuff. They just want the stuff. So they’ll take the dirt the Mexicans are making and the Cartels will sell double the amount while you’re cranking out that artisanal brand. You’re gonna price yourself out in two, three years, by my estimation.’

‘I don’t worry about the Cartels,’ Ronnie said.

‘You should,’ Peaches said, ‘because they don’t worry about you.’

Ronnie put down his drink. ‘No?’

‘You got submarines and missile launchers? Because they do.’

Ronnie thought for a moment. ‘Go on,’ he said. There was the congressman.

‘Mexican gangs keep coming in and burning our crops, snitching us out, it’s getting tiresome, but I don’t have the capital to fight them. Or the relationships. So, before they turn on you, I was hoping you might assist us in getting ourselves a foothold.’

‘What’s in it for me?’

‘I help you modernize a bit, keep you out of the newspapers, clean up some dirty dishes you still got sitting on the counter,’ Peaches said. ‘And we’re opening a casino up north. We could use your expertise on a few things.’

‘The Family is out of the casino business.’

‘Not by choice, right? Everything being equal, you’d rather still own Las Vegas, right?’

‘No,’ he said, after a while. He picked his drink back up, tossed it back. ‘I wouldn’t be happy paying workmen’s comp insurance for a thousand employees. I don’t need that.’

‘You wouldn’t be doing that with us,’ Peaches said. ‘And Howard Hughes won’t be showing up to buy you out. We’re looking at a capital infusion and then you can name your involvement. Because Mr Cupertine, I’m looking around? And I don’t see your next foray.’

‘I don’t need a next one,’ he said.

‘And yet,’ Peaches said, ‘you can’t stop your soldiers from knocking over liquor stores.’

Ronnie smiled then. ‘I’m almost entirely legal now.’

‘Which only means you’re still a crook,’ Peaches said. ‘War is coming. Isn’t gonna be guys in suits shooting each other on the streets. It’s gonna be some sixteen-year-old in a lowered Honda Civic shooting an AK out his window at you and your kids while you’re walking into Wrigley. You want to survive? You gotta move rural. That’s the next wave. That’s where the money’s going. And you want to beat the Cartels, you get out of that junk bullshit and get into pills. Oxy. Klonopin. Ambien. No one gets shot picking up a prescription from CVS. And tribes, we’ve got our clinics, our own doctors, our old folks’ homes, our own health insurance. There’s a lot of us, yeah? And we’ve got our own land and our own cops. What we don’t have is someone like you. The boss of bosses.’

Ronnie said, ‘Why haven’t I met you before?’

‘I don’t get invited to social functions.’

‘I bet,’ Ronnie said. ‘Where you from?’

‘You don’t know?’

‘I want it on tape,’ Ronnie said. Wasn’t he a smart motherfucker.

‘Wisconsin,’ Peaches said. ‘Been down here a few years. Did a couple years in West Texas, living with some cousins. Did a spot in Joliet.’

‘How long?’

‘A year.’

‘On what?’

‘Assault with a deadly weapon.’ He’d put a guy’s head through a television.

‘A year is fast.’

‘I know how to behave,’ Peaches said. ‘Plus, it happened on reservation land.’

Ronnie flipped through a stack of twenties. ‘How you know all this about fibers and DNA? You watch CSI or something?’

‘No,’ Peaches said, ‘I read books. Take criminology classes at a couple community colleges. This stuff, it’s all out in the open. You just gotta know where to look.’

‘I pay people for that,’ Ronnie said.

‘Not enough,’ Peaches said. ‘FBI could be on those cameras in five minutes. Take a sixteen-year-old probably half that time.’

‘No one knows I’m down here,’ Ronnie said. Peaches handed Ronnie one of the mailers. He opened it up, looked inside. It was filled with papers. ‘What’s this?’

‘Every piece of property you own and every piece of property you’ve hidden in the last three decades. Including that one that burned down the other day.’

‘The fuck you talking about?’

‘In Florida.’

‘Donte,’ Ronnie said, though he kept his eyes on Peaches.

The door opened up and there was that big motherfucker with the Kevlar, gun in his hand, and then behind him two other guys now. So here it was.

‘Tell the boys upstairs to give me three minutes off camera,’ Ronnie said.

‘Okay,’ Donte said. He looked at Peaches, then back at Ronnie. ‘You all right alone?’

Ronnie stared at Peaches for a few seconds. ‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘I think I’m fine.’ When Donte left, Ronnie put a finger up. ‘Don’t speak,’ he said. He looked up at the cameras. When the red light went off on all of them, he said, ‘All right. You’ve got three minutes. I don’t like what I hear, you’re leaving in a bag.’

‘I had a problem solved for you,’ Peaches said. ‘An impediment to us having any kind of fruitful association.’

‘For me? An entire fucking block of residential properties burned down,’ Ronnie said. Peaches hadn’t seen that. Mike really had a sheet now.

‘That wasn’t the intention.’

‘I got cops picking bones out of the ashes down there. It’s gonna cost me all the insurance money just to keep people quiet. So tell me, what fucking problem did you solve?’

‘A transportation problem,’ Peaches said. He tore open the second mailer, dumped out Frank Fishmann’s eyes, ears, tongue, and the skin that once covered his face. ‘Let’s have a conversation about Sal Cupertine.’

1

August 2001

That Rabbi David Cohen wasn’t Jewish had ceased, over time, to be a problem. He hardly thought of it anymore. Not when he was at the Bagel Café grabbing a nosh with Phyllis Rosencrantz to go over the Teen Fashion Show for the Homeless, not when he was shaking Abe Seigel down for a donation to the Tikvah scholarship over a bucket of balls at the TPC driving range, nor even when he was doing Shabbat services on a Saturday morning at Temple Beth Israel.

It didn’t cross his mind when he was burying some motherfucker shipped in from Los Angeles or San Francisco or Seattle, like the low-level Chinese Triad gangsters they’d been getting lately. The last one – David thought he was maybe nineteen – went into eternity under the gravestone of Howard Katz, loving husband of Jill. Or at least some of him went into eternity. Katz didn’t have much of a face left and David had his long bones extracted for transplant, then disposed of his organs, so basically he performed a service over metacarpals and phalanges in a bag of skin. Same day, David also put Morris Brinkman down, and that was fine, too. Eighty-seven years old, always crinkling butterscotch wrappers during minyan, the kind of man who still called black guys schvartzes? His time was up. Long up.

Hell, not even brises really got to David. That was all the mohel’s show, anyway, and a RICO-level scam in its own right. Schlomo Meir did the cuttings at every synagogue in town, a fucking monopoly on the foreskin business, but David didn’t see any way to move in on that. There were training courses and accreditations involved, most Reform mohels these days were nurses or EMTs, no one really wanting some shaky-hand from the Old Country wielding the knife on their son. Since David was about the only person in the room who wasn’t queasy around a blade and a little blood, it was actually a fairly pleasant affair. He could zone out for a few minutes, not worry about a tactical team kicking down the door.

No, the only time the Jewish thing crept up on David was on a day like today, the last Sunday of August, presiding over the quickie wedding of Michael Solomon to Naomi Rosen. They were too young, in David’s opinion, Naomi only twenty-two, Michael a few months younger, both just out of UNLV with degrees in golf resort management, which was a thing, apparently. The rub was that Naomi was three months pregnant and that wasn’t going to fly, at least not with her father. Jordan Rosen came to David a few weeks earlier to get a spiritual opinion on the matter, wanting to know where abortion fell among the irredeemable sins.

They were sitting in David’s office at Temple Beth Israel. He’d rearranged it since taking over from Rabbi Cy Kales, moving out the two sofas that faced each other in favor of four uncomfortable chairs surrounding a narrow coffee table. He didn’t want people staying longer than they had to.

‘Talmud says it is acceptable,’ David told him, ‘if the baby isn’t viable, or if it’s making your daughter want to harm herself.’ This was, admittedly, a pretty modern interpretation. ‘In either case, it’s not a choice you get to make for her.’

‘What if she’s not in her right mind?’

‘Is that the situation?’

‘Seems like it,’ Jordan said. ‘When I was her age, you know what I was doing?’ he asked. ‘Nothing. I was doing nothing. That’s how it should be. Make no important life decisions until you’re at least twenty-five. That’s what my father told me. Makes sense to me now. At the time, it was just a free pass to screw up without any real ramifications. It was liberating.’ Jordan squeezed his thumb and index finger over his slim mustache, thinking. Then: ‘What about killing the kid who knocked her up? What’s the ruling on that?’

‘Is he threatening your life?’

‘In a way.’

Jordan Rosen was in his late fifties and had amassed a decent fortune developing gas station mini-marts around the city, all of them called Manic Al’s. His latest venture was a carwash over on Fort Apache and Sahara that catered to the Summerlin country club set. Leather sofas. Recessed lighting. A wine bar. A cigar lounge. Seven pretty girls in knock-off Chanel suits running the front of the house like they were FBI, everything handled via earpieces, cuff mics, and disinterested stares.

Friday afternoons, Rosen brought out minor Las Vegas celebrities for meet and greets, so guys coming to pick up their Bentleys might run into Danny Gans or Charo or even Ralph Lamb, the cowboy sheriff who supposedly roughed up Johnny Roselli back in the day. It was one of those famous stories David heard growing up in Chicago, but which, when he thought about it now, seemed like it was probably made up. Good for tourism, shitty for reality. Because it turned out, what the fuck did it matter? Mob was still in Las Vegas and Ralph Lamb was still swinging his dick, fifty years later, eating free lunches for maybe smacking a guy who spent his days producing movies and counting cards. Real tough guys, both of them.

Jordan calling the car wash Manic Al’s wouldn’t fly in Summerlin, so he opted for the Millionaire Detail Club, started running commercials on KNPR, pulling in those sensitive types who listened to classical music and shopped organic but still wanted to feel like a boss, then priced everything at a markup: The most basic wash was $35.99. The Platinum Care Package ran five bills and included a blacked-out, supposedly bulletproof Suburban that would shuttle you back and forth to your home or office while your ride was getting cleaned. The Diamond Experience? Rosen didn’t bother to advertise a price on that, nor explain what it entailed. You felt the need to ask, it wasn’t for you.

David didn’t get it. It was all just water and soap. And yet there was always a line of cars waiting to get washed.

‘What does your wife think?’ David asked.

‘Sarah’s losing her mind with glee. She’s been preparing to be called Nana her entire life. Throw in planning a wedding and she might combust.’ Jordan stopped rubbing his mustache, but left his thumb in his rather pronounced Cupid’s bow, then pointed at David. ‘Can I ask you a personal question, Rabbi Cohen?’

‘If you feel you have to.’

‘Growing up, what did your parents want you to be?’

‘My own man,’ David said. That was what his mother wanted, at any rate, back when David was still her son Sal, back before he started doing hits in Chicago for the Family, back before he became the Rain Man, when she’d still acknowledge him. What his dad wanted? Sal didn’t know. He’d been dead since Sal was ten, so what he remembered about him now, almost thirty years later, were small things: How he’d pay Sal a quarter for a hug. How he read the comics in the Sun-Times first thing every morning. How he always had scabs on his knuckles.

Sometimes, Sal thought about the sound his father’s body made hitting the ground in front of the IBM Building, about how when someone gets thrown out of a fifty-two-story building, they’ve got a long time to make noise, and his father did. Screamed for a good five seconds. And then it was a liquid crunch, a spray of blood, and nothing. Sal Cupertine never did anyone like that. It wasn’t fucking human.

Rabbi David Cohen tried not to think about those things too often. He was about keeping his rage in check these days. Every morning, he wrapped tefillin on his strong arm, to remind himself of this. As a Reform Jew, it wasn’t needed, but David had adopted it anyway, thought the imagery was good, and it served a higher purpose. David couldn’t always be dialed to ten, or else he’d have nowhere to go when he really needed to be angry. Six or seven, that was his sweet spot.

‘I imagined Naomi would be a vet. She always had hamsters and silkworms and whatnot,’ Jordan said. ‘Made me sponsor a puma adoption at that gypsy zoo over on Rancho. Have you been there?’

‘I don’t believe in zoos,’ David said.

‘She didn’t either. That’s why I had to sponsor the puma. She wanted to bust it out. Place is a dump. Anyway. I don’t know. I guess that’s just me imagining a life for her.’ He stood up, cracked his neck – an annoying habit that David had noticed over the course of the last few years – then walked over to one of the three bookshelves in the office. They were six feet tall and crammed full of books on Jewish philosophy, Jewish thought, even a bit of poetry and self-help, titles like Understanding the Mishna, Understanding You. ‘You read all of these?’

‘Most of them,’ David said.

He pulled out a book of poetry, flipped it open. David didn’t like people touching his books, much less reading what he wrote in the margins. ‘Truth is,’ he said, ‘I don’t really know Naomi anymore.’ He closed the book, slipped it back into its slot, upside down, pulled out another. ‘Maybe a kid will put us into each other’s orbit again, you know? I guess that would be a side benefit.’

‘Do you know the boy?’

‘Yeah,’ he said. ‘It’s the Solomon kid. The oldest.’

‘Robert and Janice’s son?’

‘No, the other Solomons. The yenta and the ear, nose, and throat guy.’

‘Oh. Scott and Claudia?’

‘Good family, I guess. It could be worse. Few years ago, Naomi was dating a Vietnamese kid. Father dealt cards at the Orleans. One of those pinkie-ring guys who smoked funny? You know, like he held his cigarette with the wrong fingers? Anyway. Kid’s name was Binh but he called himself DJ Bomb Squad. Had it painted on his car, left stickers on light poles, even had T-shirts. I’m of the opinion it put Naomi’s grandfather into the grave prematurely.’ He snapped closed the book in his hand and put it away, right side up, then flipped over the poetry book, too. ‘It was fine with me,’ he added eventually. ‘I sort of liked DJ Bomb Squad. He was enterprising. I knew what I was getting with that kid.’

‘What happened?’

‘Who knows. One day, he’s everything, next day, Sarah tells me never to mention DJ Bomb Squad again. I almost felt sorry for him. He probably never saw it coming.’ He paused for a second, stared directly at Rabbi Cohen, which made him slightly uncomfortable. It wasn’t that he didn’t like eye contact – though that was true – it was more that he didn’t like people studying his face too closely, especially now when it felt like his face was collapsing; his jaw a fucking mess, the skin around his left eye starting to droop, and a fair amount of nasal problems were plaguing him of late, too, leaving him stuffed up half the time. There wasn’t a decent doctor he could see. Hard to get a new specialist and explain why you have titanium rods to elongate your jaw, plus a new chin and nose, and no medical records.

There was only so much his beard and a pair of glasses could hide, particularly since half the congregation were doctors of some kind. Maybe he could fake Bell’s palsy at a temple in Oklahoma, but it wasn’t going to go unnoticed in Summerlin.

‘I’m not trying to be rude,’ Jordan said, ‘but you ever think about getting Botox?’ He made a circle in the air with his index finger, pointing, generally, to David’s whole head. ‘Just a cosmetic type thing?’

‘No,’ David said. If another question about his appearance were proposed, there was a chance the next time anyone saw Jordan Rosen, it would be his photo on the news when he was reported missing.

‘I ask,’ he said, still pointing, ‘because my wife, she had that problem with her eyelid. Started to hang over her left eye?’ David remembered. She looked like a retired boxer. ‘She got it lasered and then botox froze the nerve, I guess. Something like that might help your eye. You know, if you care about such things.’

‘Talmud says all paths are crooked.’

Jordan put up his hands. ‘Fair enough,’ he said. ‘But don’t you ever think about getting married, Rabbi Cohen?’

That was now three personal questions Jordan Rosen had asked him. It was three more than David felt comfortable answering, though the marriage one was getting to be so common as to be impersonal.

‘I may well have to at some point,’ David said. It was, in fact, among his worst fears. Because Sal Cupertine was married. His wife, Jennifer, and son, William, were still in Chicago, Sal keeping watch on Jennifer’s movements in whatever way he could, even looking at her credit report online a few months back. She was racking up debt on her cards. Five grand on the Chase card. Another seven on the Citibank. A month behind on her Amex. Even the fucking Discover card was maxed out. Three and a half years since he’d seen his wife and kid and the closest he could come to them was this: peeping on their lives like some kind of pervert. He’d been able to get her money once, but since then it had become too difficult. The problem with embarrassing the FBI, turning on the Family, and pissing off the Gangster 2-6 was that it didn’t exactly make life easier.

‘It changes your perspective,’ Jordan said. ‘Sometimes, I hardly recognize myself, truth be told. Maybe it’s what Naomi needs.’

This was how it often went with the Jews: They’d come in with a problem and ask questions they’d answer themselves, as if all they needed was for David to witness the process in order to make it divine. Jordan took a deep breath, then peered around the office, as if he were seeing it for the first time even though he had spent a fair amount of time in it over the years, first meeting with Rabbi Kales and now with David. ‘You should get some pictures in here,’ Jordan said after a while. ‘Something personal.’

‘You want to know a man, read his books.’

‘That in the Talmud?’

‘No,’ David said. ‘I made that one up myself.’ Though, in fact, he hadn’t. He read it somewhere. Emerson or Whitman or maybe it was George Washington? Used to be people thought Sal Cupertine had a photographic memory, hence all that Rain Man shit, but the truth was more complex than that, David understood now. It wasn’t that he remembered every single detail of every single experience with 100 percent accuracy. He retained a lot, but that didn’t mean everything got filed with the correct headings. The last couple years – at least since all the plastic surgery – he’d felt like things weren’t quite as accurate as they’d once been. Maybe getting discount anesthesia wasn’t great on the cerebral cortex.

‘Rabbi Kales always had a lot of tchotchkes, is all.’ He stepped over to the shelf where David kept his doctored diploma from Hebrew Union in a frame on a stand.

‘He still has them,’ David said. Rabbi Kales lived in an apartment in an ‘Active Senior Living’ complex off Charleston now, on the second floor with a view of the courtyard between the two sides of the facility – the ‘active living’ portion, which was three stories and held about seventy-five people who needed only to have someone cook their meals or remind them to take their pills – and the ‘assisted living’ side, which held another hundred people on a rotating basis, seeing as it was reserved for those sliding into death, mostly in full dementia or straight-up hospice care. David thinking that if he needed to be assisted in order to live, he’d fix that quick.

‘Sarah bumped into him at Smith’s a while back.’ Jordan pulled out another book, read the back for a few seconds. ‘Said he was confused as hell.’

‘Some days he’s good,’ David said, ‘some days, not.’ That was the problem with Rabbi Kales – he wasn’t getting actual dementia fast enough. He could pretend pretty well when he needed to, but then pride would take over. David reminded him periodically that if he wanted to stay above ground, he needed to spend a bit more time out in the world acting inconsistent, particularly once his son-in-law, Bennie, was free. Rabbi Kales couldn’t drive anymore – that was part of the plan, couldn’t very well have him diagnosed as having early onset dementia and also let him keep his license – so his daughter, Rachel, either drove him places or paid for a Town Car.

‘He still makes it to services fairly regularly.’ David hadn’t seen Jordan at services since his youngest, Tricia, went off to college at Berkeley last fall. She used to come, help out with the little ones, tutor, that sort of thing. She also worked down at the Bagel Café, too, telling David she liked making her own money. David missed seeing her around. He also missed the fact that she was a shitty waitress and occasionally got his order wrong, which meant he was periodically able to wolf down a piece of bacon or sausage on the down low.

‘Well, tell him I said hello,’ Jordan said. He turned the book in his hand back over, looked at the cover, then held it up. ‘You mind if I borrow this one?’

It was a collection of notable transcripts from the Nuremberg trials. Not exactly light reading.

‘Be my guest,’ David said.

Jordan tucked the book under one arm, then took his wallet out and thumbed through his cash, pulled out two hundreds and two fifties and set them on the coffee table. ‘Appreciate the counsel, Rabbi. Come by the car wash this week,’ he said. ‘Donny Osmond is signing autographs.’

Now Naomi and Michael were exchanging a series of vows that David was pretty sure were cribbed from a pop song. The three of them stood under a chuppah in the Rosens’ backyard… if you could call anything with an acre of grass with an outdoor wine bar surrounding a private lake a yard. The Rosens lived in the Vineyards at Summerlin, a few doors down from Bennie Savone and his family, in an exclusive development that was supposed to evoke the Italian countryside except with German cars and Mexican domestic staff. David had never been to Italy, never even made it to the Venetian on the Strip to ride in a gondola, on account of the facial recognition cameras all the casinos had – they weren’t looking for average bad guys, by and large, but Bennie told him it was a no-go zone – but he couldn’t help wondering if there were housing developments being built on the Amalfi Coast modeled after Las Vegas, Italians living in peach-colored tract homes with brown lawns.

David viewed weddings as sacred affairs and took his role seriously – of all the vows he’d taken in his own life, it was the only one that had actually stuck – and if Naomi and Michael wanted to seal their love by quoting Kid Rock in front of a few hundred of their closest friends and family members, who was he to judge? Those were just words. A vow was something you believed in, and that didn’t require spoken words. Besides, it was David’s job to give them the true blessing, the sense that what they were doing had some continuity with history, so even though they weren’t particularly faithful Jews, and they exchanged bullshit vows, at least David was doing his part.

Which was the problem.