Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nine Arches Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Greekling,the much-anticipated debut poetry collection by Kostya Tsolakis, celebrates and commemorates damaged and rejected Greek bodies, be they of flesh and blood, made of marble, or natural bodies. In intertwining Greek culture, history and poetic influences with the contemporary queer experience, this collection is perceptive, lyrical, and deeply evocative of time and place. From an Athenian childhood to a closeted adolescence in the shadow of the AIDS epidemic, towards sexual self-discovery, maturity and freedom – Tsolakis charts the pursuit of unconditional happiness. These poems explore queer joy on dance floors, darkrooms and bedsits, but also the risks of crossing strangers' thresholds or in encountering the violent machismo and hypermasculine expectations of the society you grow up in. And ever-present through the collection is Athens – the city the poet once turned his back on at eighteen but has come to love again. Moving between lament and celebration, Greekling reflects on a changing and often misrepresented country, the nature of motherlands and mother tongues; it is a voyage out – and a return.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 46

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Greekling

Greekling

Kostya Tsolakis

ISBN: 978-1-913437-82-4

eISBN: 978-1-913437-83-1

Copyright © Kostya Tsolakis, 2023.

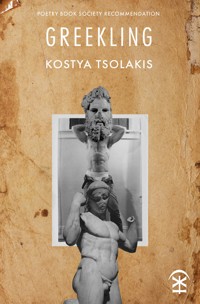

Cover artwork: ‘Greekling’ © Aaron Moth, 2023.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, recorded or mechanical, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Kostya Tsolakis has asserted his right under Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work.

First published October 2023 by:

Nine Arches Press

Unit 14, Sir Frank Whittle Business Centre,

Great Central Way, Rugby.

CV21 3XH

United Kingdom

www.ninearchespress.com

Printed in the United Kingdom on recycled paper by Imprint Digital.

Nine Arches Press is supported using public funding by Arts Council England.

Στους γονείς µου,

Ακριβό και Βασιλική Τσολάκη,

µε αγάπη.

Contents

Kifisos

Another Shore

The Case of Vangelis Yakoumakis

Tribute of Children

Ghazal: Of Them

1981

Naming It

1991

The Light-up Snowman on the Balcony

Phimosis

Bathroom in an Athens Suburb

freedom or death

On First Reading Cavafy’s ‘Caesarion’

Prickly Pear

Days of Summer, 1998

chatroom ‘99

First Time

ode to Ari’s blue shirt

Full Retraction

London Fields

on the dance floor at Heaven

marble bf

Nocturne for the American Boy I Pulled at Popstarz

Strange Pilgrims

Nobody

Kostya as a Failed State, 2011-13

Anastylosis

Sparrow

I, Wonky Nose

Patrick

what a shame,

The Dead of the Greek Enclosure in West Norwood Cemetery Speak to Me

Vine

Someone Else’s Child

Korai

Tamarisk

On Rereading Cavafy During Lockdown

Notes and Acknowledgements

Thanks

About the author and this book

Greekling

noun

a small, insignificant, or contemptible Greek

... και µέτραγα κουκίκουκί τα αισθήµατα,

τίποτα δεν αγάπησα, κανένας δεν µ’ αγάπησε.

– Ανδρέας Αγγελάκης, «Έπειτα ακόµα»

Fantastic failures of journeys occupied me…

– Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

The party was always somewhere else, at someone else’s place.

– Derek Jarman, Modern Nature

Kifisos

sad river of Athens

no one loves you

no Tiber or Seine

no one sings Κηφισέ

Κηφισέτιόµορφος

πουείσαι upriver

an unspoiled pocket

lucid waters planes

in leaf sieve the sun

an ephebos his mother

by his side sacrificed

his childhood locks

long like eels sleeked

with olive oil to your divine

current millennia later

barking dogs chained

to your banks warn

of what expects you

downstream your sacred

groves and sanctuaries

replaced by factories

pharma labs industrial parks

refuse sullies your body

forms a lurid rainbow

skin tossed rubble blocks

your flow culverts

and concrete canals

confine reroute

your natural course boxed under

a jammed motorway

no good comes out of you

fish you were home to

barbel Marathon minnow chub

gone no monument marks

your drab mouth cleaved

by a crumbling jetty

you meet the bay to noise

a looping interchange

the anchor drops

from millionaires’ yachts

chirping sparrows swoop

down peck your greasy face

as if in thirsty farewell

in summer you turn

into a stagnant thing

dry up stink the city

remembers you exist

only when it pours

tenses as you swell become

a sweeping turbid torrent

threatening to overflow

overwhelm Athens wishes

you did not exist

Another Shore

Language is never taught but eaten

in its fruit: σύκο, πεπόνι, καρπούζι, βερίκοκο.

Quarrels are hard-to-snap sea urchins

full of the roe of making up. How can you stay mad

at the man asleep in the tamarisk’s shade,

cicadas needling the hot afternoon, a wasp’s thimbleful

of pain coasting his body, skin draped in the salt

of the morning swim.

The Case of Vangelis Yakoumakis

In this marshy ditch, overlooked by naked branches,

lies the decomposing body of Vangelis. He studied

at the dairy academy nearby. Missing for thirty-seven days,

he was sighted all over Greece at once. The press

described him as sensitive, a loner. Bullies slapped him

while he ate. When he showered, they turned the water off.

Someone kicked him down a flight of stairs, someone

locked him in a closet, made him sing for hours. Then

the video: six sniggering guys piling on top of him. Thousands

heard Vangelis beg, Please stop, you’re hurting me, his voice

smaller than an olive. All this was recorded. So was the knife

found at his side. What’s lost are his features, the smooth flesh

on his cheek, where his mother would kiss him

goodbye.

Tribute of Children

Many of the conscripted boys achieved fame and fortune, rising as high as grand vizier, and sometimes parents volunteered their sons for the devshirme. But these arguments do not soften the harsh reality that for many if not most Greek families, in which ties of kinship have always been particularly strong, the removal of a son was a heartbreaking loss. – David Brewer, Greece, the Hidden Centuries

The men came, lifted us

like marble from the quarry.

A dozen budding boys –

graceful, well-bodied. I was

the youngest, no taller

than her waist, clinging

to her thigh like wax-drip

on the candlestick. Did she consider

hiding me – down the rope-cut lip

of the well, behind the thick-

threaded kilim, half-finished

on the loom? (I recall an eagle

snatching a hare; a blood-red sky.)

Did crushing my good hand

in the olive press cross

her mind? Slicing my cheek

from eyelid to jaw? But they saw me

before she saw them. As they marched us

out in our changeling uniforms –

crimson caps and tunics

paid for by our families – she watched,

stone silent, while the other mothers