Honor the Earth E-Book

9,43 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Modern History Press

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

The Great Lakes Basin is under severe ecological threat from fracking, bursting pipelines, sulfide mining, abandonment of government environmental regulation, invasive species, warming and lowering of the lakes, etc. This book presents essays on Traditional Knowledge, Indigenous Responsibility, and how Indigenous people, governments, and NGOs are responding to the environmental degradation which threatens the Great Lakes. This volume grew out of a conference that was held on the campus of Michigan State University on Earth Day, 2007.

All of the essays have been updated and revised for this book. Among the presenters were Ward Churchill (author and activist), Joyce Tekahnawiiaks King (Director, Akwesasne Justice Department), Frank Ettawageshik, (Executive Director of the United Tribes of Michigan), Aaron Payment (Chair of the Sault Sainte Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians), and Dean Sayers (Chief of the Batchewana First Nation). Winona LaDuke (author, activist, twice Green Party VP candidate) also contributed to this volume.

Adapted from the Introduction by Dr. Phil Bellfy: "The elements of the relationship that the Great Lakes' ancient peoples had with their environment, developed over the millennia, was based on respect for the natural landscape, pure and simple. The "original people" of this area not only maintained their lives, they thrived within the natural boundaries established by their relationship with the natural world. In today's vocabulary, it may be something as simple as an understanding that if human beings take care of the environment, the environment will take care of them. The entire relationship can be summarized as "harmony and balance, based on respect."

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 552

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

HONOR THE EARTH

INDIGENOUS RESPONSE TO ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION IN THE GREAT LAKES

Edited by Phil Bellfy

2nd Edition

Ziibi Press

2022

Honor the Earth: Indigenous Response to Environmental Degradation iIn the Great Lakes, 2nd Edition

Copyright © 2014, 2020, 2022 by Phil Bellfy and the Ziibi Press. All Rights Reserved.

More info at www.ZiibiPress.com

This book contains images and materials protected under International and Federal US Copyright Laws and Treaties. Any unauthorized reprint or use of this material is prohibited. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the express written permission from the authors.

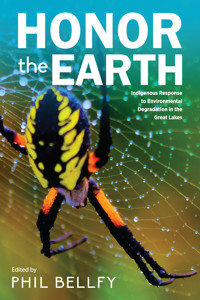

Cover photo copyright by Phil Bellfy

ISBN 978-1-61599-625-4 paperback

ISBN 978-1-61599-626-1 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-61599-627-8 eBook

Ziibi Press is an imprint of

Modern History Press

5145 Pontiac Trail

Ann Arbor, MI

www.ModernHistoryPress.com

Tollfree 888-761-6268

FAX 734-663-6861

Distributed by Ingram (USA/CAN/AU), Bertram’s Books (EU/UK)

Contents

Preface: Maaganiit Noodin — Aki: The Spirit of the Land is in Our Language

Acknowledgements

Introduction: Phil Bellfy Honor the Earth

Part I: Environmental Destruction and Indigenous Responsibility

Ward Churchill — Decolonization: A Key to the Survival of Native North America

Renée Elizabeth Mzinegiizhigo-kwe Bédard—Dreaming Amongst the Trees: Ceremony as Indigenous Education

María Cristina Manzano-Munguía—Grassroots Indigenous Epistemologies: Native, Non-Governmental Organizations, and the Environment

Part II Environmental Indigenous Imagery

Rich Fehr—Anecdote of Dominion: Industrial Sand Exploitation

David T. McNab—Weather or Not?: Weather and the Environment

Part III: Traditional Knowledge and Western Science

Deborah McGregor—First Nations, Traditional Ecological Knowledge

Aimée Cree Dunn—Listening to the Trees: Traditional Knowledge

Joel Geffen—Traditional Ecological Knowledge and the Science of Wildlife Management: Motivations for Tribal Wildlife Biologists to Protect Traditional Species

Part IV: Environmental Degradation and The Indigenous Response: The Great Lakes and Beyond

Scott Perez—Native Americans in The Great Lakes/St. Lawrence

Reddog Sina—The People and the Planet: Health Access

Winona LaDuke—The Wild Rice Moon

Aaron Payment, Cathy Abramson, Dean Sayers—The Anishnaabeg Joint Commission

Frank Ettawageshik—The Tribal and First Nations Great Lakes Water Accord

Joyce Tekahnawiiaks King—Haudenosaunee Position Paper on the Great Lakes

Part V: Vision for The Future and Conclusion

Victor Steffenson—Traditional Knowledge Revival Pathways (TKRP)

Phil Bellfy—Indigenous Response

About The Ziibi Press

PREFACE

Aki: The Spirit of the Land is in Our Language

Maaganiit Noodin

Shkaakaamikwe / Mazikaamikwe Ezhi-ni’gikenimaanaan

Miigwetch kina gwaya gii bi dagoshinoyeg miinwa bizindawiyeg.

Biindigeg,

Come in

Enji-Anishinaabemong

Where Anishinaabemowin is spoken

Enji-manjimendaming

Where there is remembering

Enji-gikendaasong

A place of knowing

Enji-zaagi'iding

A place of love

Bizandamog,

Listen

Enendamowinan zhaabobideg ode'ng

Ideas run through hearts

Bawaajigewinan waasa izhaamigag

Dreams go far

Anamejig niimiwag dibishkoo mewenzha

Those who pray dance like long ago

Kina bimaadizijig miinwaa wesiiyag owaabandaanaawaa bidaasigemigog

All the people and animals see it, the light coming

Bimaadizig

Live

Nisawayi'iing misko-biidaabang idash ni misko-pangishimag

Between the red dawn and the red sunset

Nisawayi'iing giizis idash ni niibaadibikad'giizis

Between the sun (or the month) and the full moon (time passing)

Nisawayi'iing manidoog idash wiindigoog

Between the spirits we love and the ones who devour

Nisawayi'iing awanong idash ankwadong mii ji-mikaman gdo'ojichaakam

Between the fog and the clouds you can find your soul

Biindigeg, weweni bizindamog, minobimaadizig

Come in, carefully listen, live well.

“Biindigeg, weweni bizindamog, minobimaadizig,”

I write these words as an invitation to understand our relationship with “aki / land.” She is the center of existence; the source of life, to know her is to understand the universe. To know her requires the quiet acts of listening, dreaming and believing. To know her also requires that we walk, we move across her surface, through days and nights, springs and winters, witnessing and protecting all that she is. Our relationship with her is one of science, politics, art, ecology, health, and in my case, language, especially as it rearranges itself in songs and poetry.

It is imperative that we preserve the language that allows us to better understand the Anishinaabe relationship with aki. It is equally as important that we celebrate aki by using that language, keeping that way of knowing flowing like the rivers to the oceans, because that rhythm of motion between the land and the language is one of the things that keeps us alive.

Although there are undoubtedly innumerable examples I have yet to discover, there are a few that appear most striking to me: the word “aki” and some of its relatives; the names used to talk about the life-giver Aki; and the way we talk about what we do with her gift of life.

Aki is such a small word and yet, many language teachers believe that the smallest, simplest pieces of meaning are possibly the oldest. Aki is certainly one of the first terms Anishinaabeg must have needed to begin speaking of who, where and why we are. The aadisokaanag / stories are long and beautifully complex, but many begin with the belief that Gizhemanido had a vision which led to the creation of the universe including the rock, water, fire and wind that become Aki who in these old stories she is often called by one of two names, Shkaakaamikwe or Mazikaamikwe.

Although I can only make intelligent guesses about the roots of these words it is important to note that neither of them are as simply as “Gashwan Aki.” To call her by her name in Anishinaabemowin implies much more than the ground personified. Both Shkaakaamikwe and Mazikaamikwe end with “ikwe,” the term for woman, so she must be considered a representation of that force we know as one half of human construction, but used in this way, that little word-part is used more for balance and identity, not the creation of a stereotype.

One of the beautiful aspects of the old ways is that, like the language itself, there is no constant designation of he or she, but rather a mention of inini (man) or (ikwe) woman, male or female, only as needed, most often in names, and always after the action has been described. In fact, it is in akiwenzii, the word for old man that we find aki, perhaps to remind us that he too, is our partner in protecting and producing life with our mother.

The two names, Shkaakaamikwe and Mazikaamikwe, differ significantly and may simply be names without assigned meanings, but Anishinaa-bemowin words are often poems unto themselves, strings of meaning that create a mosaic of understanding. In these words I hear what I know she does, “mazi” is a piece of language often used to speak about something made into an image: “mazinaadin” is to make an image, “mazinibii” to draw, “mazinaabidoo’an” to bead on a loom, “mazina’igan” a page or book.

Speakers must consciously or unconsciously think of these creative images when they hear or say Mazikaamikwe. Shkaakaamikwe is less obvious, but in it, I hear “zhakaa” which is a piece of meaning added to indicate something is soft and damp, like snow or a bog. One could also consider the phrase “oshki ogimaa kwe,” which roughly translates to the “new leading woman.” And when we think of where old stories (and now science) tell us life began, I think both may be related to the concept.

These are the names for aki, the earth, the one we know as a mother. I think of them when we sing our song for her, and her daughters of the four directions who rise each morning and walk in the four directions across her landscape, her body, and our souls.

Shkaakaamikwe,

Mazikaamikwe,

G’daanisag bmosewag

Giiwedinong

Waabanong

Zhowaanong

Epangishimag

I added Anishinaabe lyrics to a song by Brenda MacIntyre who says “this song came to help heal the people.” I could think of no better way to honor our connection to Aki than to sing of her and her daughters, the four sisters, who protect the processes of birth and death, the cycle of seasons and journey of our souls.

We call this journey, “minobimaadiziwin.” This is significant in thinking about our mother, the earth, when we recognize the rhythm of bmode, bmose, bmpato, bmise, bgizo. Akina goya (all of us) living on earth crawl, or walk, or run, or fly, or swim. These words are like a song sung in our hearts as we move and live with Aki. It is she who allows us to do these things and it is our language that allows us to connect them in our minds with life, movement, well-being. We are the “aki” in “akina goya.”

We are part of this waawii’ok bimaadiziwin (this circle of life). G’gii niigimin miidash ombigiying miidash ininiwiying maage ikwewiying. (We are born and then grow up as men and women.) What we must remember is: Gego banaajtooken ezhi-bimaadziying neyaab g’daa biidoomin Anishinaabe-bimaadiziying. (Don’t break the way of life, we need to bring back the Anishinaabe way of living.) We need to honor the old ways of knowing and understanding our world and ourselves.

As we strive to blend ancient philosophy, theology and ecological beliefs with a modern world, I am inspired by those who have gone before me and those who lead me know. In particular, I think of the women who began the Mother Earth Waterwalk in 2007 to raise awareness about our water. These women continue to remind us, "water is precious and sacred… it is one of the basic elements needed for all life to exist."

They have circled, Superior, Michigan, Huron, Ontario and Erie, all of which we call Chigaming. These gentle women are some of the daughters of the Earth I admire most. They are not presidents of countries or companies, they are not rock stars or billionaires, but they are living vessels of water and spirit and I am certain that as Gizhemanido looks down upon the earth, they shine more brightly than anything that has been made by humanity. I know Nokomis Nibaagiizis will be with them night and day, as will many of us in spirit.

Another Mother that I must mention when speaking of those who artfully balanced the demands of motherhood, bimaadiziwin, and rapidly changing times on this earth, is Jane Johnston Schoolcraft. Although she lived over 100 years ago, her concerns and beliefs are still a useful mirror for our times. She knew many worlds and lived successfully in several. And she should be recognized as the mother of modern Anishinaabe poetry. Although she could write like Poe or Longfellow in elegant and flowing English, it is her simple works in Anishinaabemowin that I like the most.

Robert Dale Parker published a book that carves for her a rightful place in the literature of American letters. In cooperation and response to these efforts, John Nichols gave readers a treasure when he re-transcribed one of her poems making it clear it was most likely written as a song sung to her children when she made the difficult choice to leave them at school.

The title she chose was simply, “Nindinendam (I am thinking)” and the most frequent word used is, not surprisingly, “endanakiiyaan” (my homeland), a combination of endayaan and akii that reflects what this land can and should mean to all of us, kina goya. Her verses are simple and clear.

Nyaa nindinendam Oh I am thinking

Mekawiyaanin I am reminded

Endanakiiyaan Of my homeland

Waasawekamig A faraway place

Endanakiiyaan My homeland

Nidaanisens e My little daughter

Nigwizisens e My little son

Ishe naganagwaa I leave them far behind

Waasawekamig A faraway place

Endanakiiyaan My homeland

Zhigwa gosha wiin Now

Beshowad e we It is near

Ninzhike we ya I am alone

Ishe izhayaan As I go

Endanakiiyaan My homeland

Endanakiiyaan My homeland

Ninzhike we ya I am alone

Ishe giiweyaan I am going home

Nyaa nigashkendam Oh I am sad

Endanakiiyaan My homeland

And when I sing this song now, gathering strength to face a new day, I add these lines to mark the way I long for my own daughters, now growing into their own lives, sometimes separated from me as I work on recovering the sound of the widening space we call home together. I sing it and wonder about the way love opens even as it is spilled. G’zaaginim n’daanisag miinwaa pane giizis zaagiaasiged pii zoongide-zagajigaba-wiying.

N’daanisensag My daughters

Ikwesensag My girls

nd’gikendamin we know it

kchi’zaaginagog I love you so much

zaagiyeg gaye. and you both love me too.

May this book be a Anishinaabe love song to Aki from all her sons and daughters.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Maaganiit Noodin received an MFA in Creative Writing and a PhD in English and Linguistics from the University of Minnesota. She is Assistant Professor in English and American Indian Studies and at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Her book Bwaajimo: A Dialect of Dreams in Anishinaabe explores the Anishinaabe language in literature. She has published poetry in numerous journals and magazines and sings with Miskwaasining Nagamojig (the Swamp Singers) a women’s hand drum group whose lyrics are all in Anishinaabemowin. It is as a daughter, and for her daughters, that she continues to connect sounds in this space of Great Lakes.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Acknowledgements

This volume grew out of a conference that was held on “Earth Day” weekend in April of 2007 on the campus of Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan. All of the essays that appear in this book have been reviewed and updated by the authors for this (Second) edition.

The Earth Day conference and this book could not have happened without the generous support of the Canadian Embassy in Washington, DC, and the Canadian Consulate in Detroit. Dennis Moore, of the Detroit Consulate, deserves special miigwetch, merci, and thanks for his unwavering support.

The conference was also supported by the Canadian Studies Centre at Michigan State University, under the Acting Directorship, in 2007, of Phil Handricks,.

Conference organizers would also like to thank these additional sponsors for their support: MSU College of Arts and Letters, MSU American Indian Studies Program, and the MSU North American Indigenous Faculty and Staff Association.

The conference was organized by the Center for the Study of Indigenous Border Issues (CSIBI). CSIBI Co-directors are: Phil Bellfy (Professor Emeritus of American Indian Studies, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan), Karl Hele (Associate Professor Mount Allison University, Sackville, New Brunswick), and David McNab (at the time of this conference, Dr. McNab was Associate Professor of Indigenous Thought and Canadian Studies, Departments of Equity Studies and Humanities, Faculty of Liberal Arts and Professional Studies at York University, Toronto;). CSIBI’s publishing arm is the Ziibi Press. This volume is published under that imprint.

More information on CSIBI and the Ziibi Press can be found at:

<ZiibiPress.org>

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

INTRODUCTION

Honor The Earth

Phil Bellfy

The Great Lakes were first visited by Europeans over four hundred years ago, and since then, the Lakes’ environs have been severely altered. The evidence can be seen everywhere—massive multi-lane highways, huge mega-cities, large-scale technological “improvements” that have altered vast landscapes, mines, power-plants, nuclear generating stations, paper mills, steel smelters, water diversion projects—the list goes on and on. In technology’s wake, we see pollution of our air, our water, our land, and even our own bodies.

But, if you look hard enough, you can find some areas that appear to be untouched by the Westerners’ hand. The North Shore of Lake Superior is one of those places. Here you will find immense rock outcroppings covered in forest, lakes teeming with fish, moose and deer and bear foraging seemingly everywhere. You will also find ancient pictographs along the shore, and “pukaskwas” –small holes dug out of the huge boulder “beaches” found along the north shoreline of Lake Superior. These boulder beaches are often found a mile or so inland from the existing shoreline, marking the shoreline of an earlier “Lake Superior” which was more vast and deeper than the lake of today.

Imagine a sloping field of boulders covering perhaps an area as large as a football field or larger. The boulders vary in size, from the smallest being perhaps the size of a softball, the largest, beach-ball size. The “surface” of this boulder beach is rather smooth, even though inclined, sloping down toward the lake. Within this landscape (rockscape, would be a better term) you may notice an occasional “depression,” an area where the rocks have been “excavated,” heaped up along the ridge of the hole that is being created. The hole itself may be no deeper than three feet; the boulders moved in its creation may number no more than a few dozen.

It is claimed that no one knows why the ancient people of the region created these pukaskwa holes –they seem to serve no purpose that we can decipher. They’re too small to have served as shelter; besides, shelter would have been more readily obtained in the forests that surround these boulder beaches. They certainly aren’t “mines” in the sense that we might imagine people "excavating” in these boulder beaches for some thing of value –there’s nothing but boulders everywhere (in fact, what now passes for “forest” is simply a bunch of trees growing on top of even more “boulder-beach,” now covered with a thin layer of soil after who knows how many millennia).

In the case of the pictographs, we can at least see some cultural reason for their creation, as they often depict human figures, Thunderbirds, or Misshupeshu, the Spirit of the lake. But not so for the pukaskwa “holes.”

Of course, we (those of us alive today) are not completely ignorant about those who inhabited these areas long ago –those we may call the Ancient Ones. If you will allow me a little speculation: we know that the pictographs served to depict events and spirits of the places where the Ancient Ones painted them on those rock faces millennia ago. We know that these practices formed just one element of the Ancient Ones “cosmology” –that “body of knowledge” which constituted their ancient Way of Life. Some of those ancient ways have come down to us today as elements of what many may call “Indian religion.”

So, based on what we know today, and basing our speculation on that knowledge, I think that it’s safe to assume that the pukaskwa holes served—in whatever capacity—as elements of the relationship that the Great Lakes’ ancient peoples had with their environment, in whatever spiritual configuration that image may conjure up in your own imagination. And, we can be sure that whatever visible form that sacred relationship may have taken –pictographs, pukaskwa holes—we can be certain that the relationship was based on respect for the natural landscape, pure and simple.

It was through this respectful relationship, developed over the millennia, that the “original people” of this area not only maintained their lives, they thrived within the natural boundaries established by their relationship with the natural world. In today’s vocabulary, it may be something as simple as an understanding that if human beings take care of the environment, the environment will take care of them. The entire relationship can be summarized as “harmony and balance, based on respect.”

Of course, here we are today, in the Third Millennium, struggling to maintain our "way of life.”

As “technological people,” we have destroyed much of our environment, and those of us in the Great Lakes cannot escape from the responsibility for much of our actions. We are told to not eat too many fish caught in the Great Lakes; often, in our cities, old people and infants are told to remain indoors as the air is too befouled to be breathed; asthma is reaching epidemic proportions; occasionally, beaches are closed to swimming due to an increased risk of bacterial infection; sometimes people die from drinking contaminated water, others “just” get sick; the same is true of our food supply –many get sick and some die; our bodies often become ravaged by cancer and other environmentally-induced diseases, which often kill us; and, in what is to me the most revealing caution, we are told to “stay out of the sun” as the danger of skin cancer lurks in every ray.

Don’t breathe the air, don’t eat the food, don’t drink the water, don’t even stand outside in the daylight. This is the state of “modern civilization” and the state of "modern” humans –“living” within the confines of a polluted world, surrounded by a multitude of “things.” This is doubly true for us in the Great Lakes region –home of the “rust belt” and its attendant environmental ills. Our Lakes are polluted, as are our rivers, many of us are sick, we are battling “invasive species” which are taking an additional toll on our resources, devastating our “indigenous” flora and fauna.

But many of us are not sitting idly by watching our TVs and waiting for the “final episode” to be aired; many of us have become “environmental activists” simply because to be otherwise would be to acquiesce in our own destruction. Many Native people of the Great Lakes have, too, become “environmentalists,” although they may have been living that Way of Life long before it became “trendy” to be so called. It goes back to those Ancient Ones, those who came long before us, those who lived their lives in harmony and balance with the Natural World, aided in this relationship by mutual respect.

There is also something to be said for living close to the natural world, as Native people have been “restricted” to “reservations” which are often “out of the way” places that were considered to be of “no use” to the early Europeans. It is also true that these “natural areas” are those with no mineral “wealth” or other resources held in high regard by the dominant culture today. Hence, simply by history, and out of necessity, Native people live “close to the land.”

Even though they live far from the “benefits” of “civilization,” Native people have also been among those most affected by “modern” pollution. If they eat their “natural” diet, rich in the bounty of the lakes and rivers, they are in danger of consuming amounts of mercury and carcinogenic substances far in excess of “allowable” standards. As we shall see in some of the essays which comprise this book, they often live “down-stream” from factories that discharge industrial pollution.

I encourage the readers of this volume to keep in mind that Ancient dictum –live in harmony and balance with the natural world, and do so ever mindful of the respect that that natural world deserves. We shall attempt to trace that relationship throughout these essays, and give you at least a slight glimpse back into an earlier time, spend some time on the conditions of the present, and a short vision of a possible future.

The Preface, which you have already read, sets the stage for what follows. It gives us (all of us, Native and non-Native) the underlying “philosophy” of respect –it’s built into the language of Great Lakes’ Indigenous people, and, consequently, it comprises the foundation of our worldview.

The next section, “Environmental Destruction and Indigenous Respon-sibility,” presents a few essays that expand on Maaganiit Noodin's Preface, exploring the foundations of Indigenous Identity and responsibility and our relationship to the environment.

We then move into an examination of some Great Lakes environmental history through the eyes of some historical figures and observations in the section titled “Environmental Indigenous Imagery,” The “Traditional Knowledge and Western Science” section details how “Indigenous Ways of Knowing” relate to “traditional” western science and the implications of “science” on the lives of all of us (again, Native and non-Native).

The next section of this book, “Environmental Degradation and the Indigenous Response: the Great Lakes and Beyond,” deals with some “(Sweet)grass-roots” action –specific examples of environmental destruction and how some Indigenous groups have chosen to work toward a future that reflects Indigenous values, and does so in the hope that the “harmony and balance,” mentioned at the beginning of this volume, can be, once again, brought into force here in the Great Lakes.

This volume ends with a brief description of the Traditional Knowledge Revival Pathways project of the Aboriginal people of Australia. And, finally, I present a “vision for the future” of the Indigenous Great Lakes. Every bit of what I write is echoed in the essays and the commitment of “All Our Relations,” and the vision presented by each and every one of our committed and competent contributors.

◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊ ◊

Part I: Environmental Destruction and Indigenous Responsibility

Decolonization: A Key to the Survival of Native North America

Ward Churchill

The Europeans who began taking over the New World in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were not ecologists. Although they were compelled to realize that the Americas were not quite uninhabited, they were not prepared to recognize that these new lands were, in an ecological sense, much more than “sparsely” inhabited. This second hemisphere was, in fact, essentially “full.”

--William Catton -- Overshoot

The standard Euroamerican depiction of “pre-contact” Native North Americans has long been that the relative handful of us who existed wandered about perpetually in scattered bands, grubbing out the most marginal subsistence by hunting and gathering, never developing writing or serious appreciations of art, science, mathematics, governance, and so on. Aside from our utilization of furs and hides for clothing, the manufacture of stone implements, use of fire, and domestication of the dog, there is little in this view to distinguish us from the higher orders of mammalian life surrounding us in the “American wilderness.”(1)

The conclusions reached by those who claim to idealize “Indianness” are little different at base from the findings of those who openly denigrate it: Native people were able to inhabit the hemisphere for tens of thousands of years without causing appreciable ecological disruption only because we lacked the intellectual capacity to create social forms and technologies that would substantially alter our physical environment. In effect, a sort of socio-cultural retardation on the part of Indians is typically held to be responsible for the pristine quality of the Americas at the point of their “discovery” by Europeans.(2)

In contrast to this perspective, it has recently been demonstrated that, far from living hand-to-mouth, “Stone Age” Indians adhered to an economic structure that not only met their immediate needs but provided considerable surpluses of both material goods and leisure time.(3) It has also been established that most traditional native economies were based in agriculture rather than hunting and gathering—a clear indication of a stationary, not nomadic, way of life—until the European invasion dislocated the indigenous populations of North America.(4)

It is also argued that native peoples’ long-term coexistence with our environment was possible only because of our extremely low population density. Serious historians and demographers have lately documented how estimates of pre-contact indigenous population levels were deliberately lowered during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in order to lessen the implications of genocide bound up in the policies of the U.S., Canada and their colonial antecedents.(5) A noted ecologist has also recently determined that, rather than being dramatically underpopulated, North America was in fact saturated with people in 1500. The feasible carrying capacity of the continent was, moreover, outstripped by the European influx by 1840, despite massive reductions of native populations and numerous species of large mammals.(6)

Another myth is contained in the suggestion that indigenous forms of government were less refined than those of their European counterparts. The lie is put to this notion, however, when it is considered that the enlightened republicanism established by the United States during the late 1700s—usually considered an advance over then-prevailing European norms—was lifted directly from the model of the currently still functioning Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) confederacy.(7) In many ways the Haudenosaunee were indicative of political arrangements throughout Native North America.(8) American Indians evidenced similar achievements in preventative medicine, mathematics, astronomy, architecture and engineering, all without engendering appreciable environmental disruption.(9) Such a juxtaposition of advanced socio-cultural matrices and sustained ecological equilibrium is inexplicable from the vantage point of conventional Euro-derivative assumptions.

Unlike Europeans, Native Americans long ago attained a profound intellectual apprehension that human progress must be measured as an integral aspect of the natural order, rather than as something apart from and superior to it. Within this body of knowledge, elaborated and perfected through oral tradition and codified as “law” in ceremonial/ritual forms, the indigenous peoples of this hemisphere lived comfortably and in harmony with the environment, the health of which was recognized as an absolute requirement for our continued existence.(10)

In simplest terms, the American Indian world view may be this: Human beings are free—indeed, encouraged—to develop our innate capabilities, but only in ways that do not infringe upon other elements—called “relations,” in the fullest dialectical sense of the word—of nature. Any activity going beyond this is considered as “imbalance,” a transgression, and is strictly prohibited. Engineering, for example, was and is permissible, but only insofar as it does not permanently alter the earth itself. Similarly, agriculture was widespread, but only within parameters that did not supplant natural vegetation.(11)

Key to the indigenous American outlook is a firm acknowledgment that the human population may expand only to the point, determined by natural geographic and environmental circumstances, where it begins to displace other animal species and requires the permanent substitution of cropland for normal vegetation in any area. North America’s aboriginal populations never entered into a trajectory of excessive growth, and, even today, many native societies practice a self-regulation of population size that allows the substance of our traditional worldviews with their interactive environmental relationships to remain viable.(12)

Cultural Imperialism

They came for our land, for what grew or could be grown on it, for the resources in it, and for our clean air and pure water. They stole these things from us, and in the taking they also stole our free ways and the best of our leaders, killed in battle or assassinated. And now, after all that, they’ve come for the very last of our possessions; now they want our pride, our history, our spiritual traditions. They want to rewrite and remake these things, to claim them for themselves. The lies and thefts just never end.

--Margo Thunderbird -- 1988

Within the industrial wasteland of the early twenty-first century, such traditional perspectives are deformed right along with the physical dimensions of indigenous culture. Trivialized and co-opted, they have been reduced to the stuff of the settler society’s self-serving pop mythology, commercialized and exploited endlessly by everyone from the Hollywood moguls and hippie filmmakers who over the past 75 years have produced literally thousands of celluloid parodies not merely of our histories, but of our most sacred beliefs, to New Age yuppie airheads like Lynne Andrews who pen lucrative “feminist” fables of our spirituality, to the flabbily over-privileged denizens of the “Men’s Movement” indulging themselves in their “Wildman Weekends,” to pseudo-academic frauds like Carlos Castaneda who fabricate our traditions out of whole cloth, to “well-intentioned friends” like Jerry Mander who simply appropriate the real thing for their own purposes. The list might easily be extended for pages.(13)

Representative of the mentality is an oft-televised public service announcement featuring an aging Indian, clad in beads and buckskins, framed against a backdrop of smoking factory chimneys while picking his way carefully among the mounds of rusting junk along a well-polluted river. He concludes his walk through the modern world by shedding a tragic tear induced by the panorama of rampant devastation surrounding him. The use of an archaic Indian image in this connection is intended to stir the settler population’s subliminal craving for absolution. “Having obliterated Native North America as a means of expropriating its land-base,” the subtext reads, “Euroamerica is now obliged to ‘make things right’ by preserving and protecting what was stolen.” Should it meet the challenge, presumably, not only will its forebears’ unparalleled aggression at last be in some sense redeemed, but so too will the blood-drenched inheritance they bequeathed to their posterity be in that sense legitimated. The whole thing is of course a sham, a glib contrivance designed by and for the conquerors to promote their sense of psychic reconciliation with the facts and fruits of the conquest.(14)

A primary purpose of this essay is to disturb—better yet, to destroy altogether—such self- serving and -satisfied tranquility. In doing so, its aim is to participate in restoring things Indian to the realm of reality. My hope is that it helps in the process to heal the disjuncture between the past, present and future of Native North American peoples which has been imposed by more than four centuries of unrelenting conquest, subjugation and dispossession on the part of Euroamerica’s multitudinous invaders. This does not make for pleasant reading, nor should it, for my message is that there can be no absolution, no redemption of past crimes unless the outcomes are changed. So long as the aggressors’ posterity continue to reap the benefits of that aggression, the crimes are merely replicated in the present. In effect, the aggression remains ongoing and, in that, there can be no legitimacy. Not now, not ever.

Contemporary Circumstances

We are not ethnic groups. Ethnic groups run restaurants

serving “exotic” foods. We are nations.

-- Brooklyn Rivera - 1986

The current situation of the indigenous peoples of the United States and Canada is generally miscast as being that of ethnic/racial minorities. This is a fundamental misrepresentation in at least two ways. First, there is no given ethnicity which encompasses those who are indigenous to North America. Rather, there are several hundred distinctly different cultures—“ethnicities,” in anthropological parlance—lumped together under the catch-all classification of “Native Americans” (“Aboriginals” in Canada). Similarly, at least three noticeably different “gene stocks”—the nomenclature of “race”—are encompassed by such designators. Biologically, “Amerinds” like the Cherokees and Ojibwes are as different from Inuits (“Eskimo-Aleuts”) and such “Athabascan” (“Na-Dene”) types as the Apaches and Navajos as Mongolians are from Swedes or Bantus.(15)

Secondly, all concepts of ethnic or racial minority status fail conspicuously to convey the sense of national identity by which most or all North American indigenous populations define ourselves. Nationality, not race or ethnicity, is the most important single factor in understanding the reality of Native North America today.(16) It is this sense of ourselves as comprising coherent and viable nations which lends substance and logic to the forms of struggle in which we have engaged over the past half-century and more.(17)

It is imperative when considering this point to realize that there is nothing rhetorical, metaphorical or symbolic at issue. On the contrary, a concrete and precise meaning is intended. The indigenous peoples of North America—indeed, everywhere in the hemisphere—not only constituted but continue to constitute nations according to even the strictest definitions of the term. This can be asserted on the basis of two major legal premises, as well as a range of more material considerations. These can be taken in order.

• To begin with, there is a doctrine within modern international law known as the “right of inherent sovereignty” holding that a people constitutes a nation, and is thus entitled to exercise the rights of such, simply because it has done so “since time immemorial.” That is, from the moment of its earliest contact with other nations the people in question have been known to possess a given territory, a means of providing their own subsistence (economy), a common language, a structure of governance and corresponding form of legality, and a means of determining membership/social composition. As was to some extent shown above, there can be no question but that Native North American peoples met each of these criteria at the point of initial contact with Europeans.(18)

• Second, it is a given of international law, custom and convention that treaty-making and treaty relations are entered into only by nations. This principle is constitutionally enshrined in both U.S. and Canadian domestic law. Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution, for instance, clearly restricts treaty-making prerogatives to the federal rather than, state, local or individual levels. In turn, the federal government itself is forbidden to enter into a treaty relationship with any entity aside from another fully sovereign nation (i.e., it is specifically disempowered from treating with provincial, state or local governments, or with corporations and individuals). It follows that the U.S. government’s entry into some 400 ratified treaty relationships with North America’s indigenous peoples— an even greater number prevail in Canada—abundantly corroborates our various claims to sovereign national standing.(19)

Officials in both North American settler states, as well as the bulk of the settler intelligentsia aligned with them, presently contend that, while native peoples may present an impeccable argument on moral grounds, and a technically valid legal case as well, pragmatic considerations in “the real world of the new millenium” precludes actualization of our national independence, autonomy, or any other manifestation of genuine self-determination. By their lights, indigenous peoples are too small, both in terms of our respective land-bases/attendant resources and in population size(s), to survive either militarily or economically in the contemporary international context.(20)

At first glance, such thinking seems plausible enough, even humane. Delving a bit deeper, however, we find that it conveniently ignores the examples of such tiny European nations as San Marino, Monaco and Liechtenstein, which have survived for centuries amidst the greediest and most warlike continental setting in the history of the world. Further, it blinks the matter of comparably-sized nations in the Caribbean and Pacific Basins whose sovereignty is not only acknowledged, but whose recent admissions to the United Nations have been endorsed by both Canada and the U.S. Plainly, each of these countries is at least as militarily vulnerable as any North American Indian people. The contradictions attending U.S. /Canadian Indian policy are thus readily apparent to anyone willing to view the situation honestly. The truth is that the states’ “humanitarianism” is in this connection no more than a gloss meant to disguise a very different set of goals, objectives and sensibilities.

Nor do arguments to the “intrinsic insolvency” of indigenous economies hold up to even minimal scrutiny. The Navajo Nation, for instance, possesses a land-base larger than those of Monaco, Fiji and Grenada combined. Within this area lies an estimated 150 billion tons of low sulfur coal, about forty percent of “U.S.” uranium reserves and significant deposits of oil, natural gas, gold, silver, copper and gypsum, among other minerals. This is aside from a limited but very real grazing and agricultural capacity.(21) By any standard of conventional economic measure, the Navajos—or Diné, as they call themselves—have a relatively wealthy resource base as compared to many Third World nations and more than a few “developed” ones. To hold that the Navajo Nation could not survive economically in the modern world while admitting that Grenada, Monaco and Fiji can is to indulge in sheer absurdity (or duplicity).

While Navajo is probably the clearest illustration of the material basis for assertions of complete autonomy by Native North American nations, it is by no means the only one. The combined Lakota reservations in North and South Dakota yield an aggregate land-base even larger than that of the Diné and, while it exhibits a somewhat less spectacular range of mineral assets, this is largely offset by a greater agricultural/grazing capacity and smaller population size.(22) Other, smaller, indigenous nations possess land-bases entirely adequate to support their populations and many are endowed with rich economic potentials which vary from minerals to timbering to ranching and farming to fishing and aquaculture. Small-scale manufacturing and even tourism also offer viable options in many instances.(23)

All this natural wealth exists within the currently-held native land-base (“reserves” in Canada, “reservations” in the U.S.). Nothing has been said thus far about the possibility that something approximating a just resolution might be effected concerning indigenous claims to vast territories retained by treaty—or to which title is held through unextinguished aboriginal right—all of which has been unlawfully expropriated by the two North American settler states.(24) Here, the Lakota Nation alone would stand to recover, on the basis of the still-binding 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, some five percent of the U.S. 48 contiguous states area. The region includes the Black Hills, reputedly the 100 most mineral-rich square miles on the entire planet.(25) All told, naturalization of persons residing within the treaty areas—or those who might wish to relocate there for purposes of placing themselves under native rather than U.S./Canadian jurisdiction—would likely increase the citizenry of Native North America by several millions.(26)

In sum, just as the indigenous peoples of North America “once” possessed the requisite ingredients of nationhood, so too do we continue to possess them. This is true whether one uses as one’s point(s) of reference the dimension of our territories, the basis of our economies, the size of our populations, or any other reasonable criteria. Perhaps most important in a legal sense, as well as in terms of ethics and morality, we continue to hold our inherent rights and standing as nations because, quite simply and undeniably, we have never voluntarily relinquished them. To argue otherwise, as so many settler officials and “scholars” are prone to do, is to argue the invalidity of the Law of Nations.(27)

Sharing the Land

There are several closely related matters which should be touched upon before wrapping this up. One has to do with the idea of self-determination. What is meant when indigenists demand an unrestricted exercise of self-determining rights by native peoples? Most non-Indians, and even a lot of Indians, seem confused by this and want to know whether it’s not the same as complete separation from the U.S., Canada, or whatever the colonizing power may be. The answer is, “not necessarily.” The unqualified acknowledgment by the colonizer of the right of the colonized to total separation (“secession”), is the necessary point of departure for any exercise of self-determination. Decolonization means the colonized exercise the right in whole or in part, as we see fit, in accordance with our own customs, traditions and appreciations of our needs. We decide for ourselves what degree of autonomy we wish to enjoy, and thus the nature of our political and economic relationship(s), not only with our former colonizers, but with all other nations as well.(28)

My own inclination, which is in some ways an emotional preference, tends to run toward complete sovereign independence, but that’s not the point. I have no more right to impose my preferences on indigenous nations than do the colonizing powers; each indigenous nation will choose for itself the exact manner and extent to which it expresses its autonomy, its sovereignty.(29) To be honest, I suspect very few would be inclined to adopt my sort of “go it alone” approach (and, actually, I must admit that part of my own insistence upon it often has more to do with forcing concession of the right from those who seek to deny it than it does with putting it into practice). In the event, I expect you’d see the hammering out of a number of sets of international relations in the “free association” vein, a welter of variations of commonwealth and home rule governance.(30)

The intent here is not, no matter how much it may be deserved in an abstract sense, to visit some sort of retribution, real or symbolic, upon the colonizing or former colonizing powers. It is to arrive at new sets of relationships between peoples which effectively put an end to the era of international domination. The need is to gradually replace the existing world order with one which is predicated in collaboration and cooperation between nations.(31) The only way to ever really accomplish that is to physically disassemble the gigantic state structures which evolved from the imperialist era, structures which are literally predicated in systematic inter-group domination and cannot in any sense exist without it.(32) A concomitant of this disassembly is the inculcation of voluntary, consensual interdependence between formerly dominated and dominating nations, and a redefinition of the word “nation” itself to conform to its original meaning: bodies of people bound together by their bio-regional and other natural cultural affinities.(33)

This last point is, it seems to me, crucially important. Partly, that’s because of the persistent question of who it is who gets to remain in Indian Country once land restoration and consolidation has occurred. The answer, I think, is anyone who wants to, up to a point. By “anyone who wants to,” I mean anyone who wishes to apply for formal citizenship within an indigenous nation, thereby accepting the idea that s/he is placing him/herself under unrestricted Indian jurisdiction and will thus be required to abide by native law.(34)

Funny thing; I hear a lot of non-Indians asserting that they reject nearly every aspect of U.S. law, but the idea of placing themselves under anyone else’s jurisdiction seems to leave them pretty queasy. I have no idea how many non-Indians might actually opt for citizenship in an Indian nation when push comes to shove, but I expect there will be some. And I suspect some Indians have been so indoctrinated by the dominant society that they’ll elect to remain within it rather than availing themselves of their own citizenship. So there’ll be a bit of a trade-off in this respect.

Now, there’s the matter of the process working only “up to a point.” That point is very real. It is defined, not by political or racial considerations, but by the carrying capacity of the land. The population of indigenous nations everywhere has always been determined by the number of people who could be sustained in a given environment or bio-region without overpowering and thereby destroying that environment.(35) A very carefully calculated balance—one which was calibrated to the fact that in order to enjoy certain sorts of material comfort, human population had to be kept at some level below saturation per se—was always maintained between the number of humans and the rest of the habitat. In order to accomplish this, Indians incorporated into the very core of their spiritual traditions the concept that all life forms and the earth itself possess rights equal to those enjoyed by humans.(36)

Rephrased, this means it would be a violation of a fundament of traditional Indian law to supplant or eradicate another species, whether animal or plant, in order to make way for some greater number of humans, or to increase the level of material comfort available to those who already exist. Conversely, it is a fundamental requirement of traditional law that each human accept his or her primary responsibility, that of maintaining the balance and harmony of the natural order as it is encountered.(37) One is essentially free to do anything one wants in an indigenous society so long as this cardinal rule is adhered to. The bottom line with regard to the maximum population limit of Indian Country as it has been sketched in this presentation is some very finite number. My best guess is that five million people would be pushing things right through the roof.(38) Whatever. Citizens can be admitted until that point has been reached, and no more. And the population cannot increase beyond that number over time, no matter at what rate. Carrying capacity is a fairly constant reality; it tends to change over thousands of years, when it changes at all.

Population and Environment

What I’m going to say next will probably startle a few people (as if what’s been said already hasn’t). I think this principle of population restraint is the single most important example Native North America can set for the rest of humanity. It is the thing which it is most crucial for others to emulate. Check it out. I recently heard that Japan, a small island nation which has so many people that they’re literally tumbling into the sea, and which has exported about half again as many people as live on the home islands, is expressing “official concern” that its birth rate has declined very slightly over the last few years. The worry is that in thirty years there’ll be fewer workers available to “produce,” and thus to “consume” whatever it is that’s produced.(39)

Ever ask yourself what it is that’s used in “producing” something? Or what it is that’s being “consumed”? Yeah. You got it. Nature is being consumed, and with it the ingredients which allow ongoing human existence. It’s true that nature can replenish some of what’s consumed, but only at a certain rate. That rate has been vastly exceeded, and the extent of excess is increasing by the moment. An over-burgeoning humanity is killing the natural world, and thus itself. It’s no more complicated than that.(40)

Here we are in the midst of a rapidly worsening environmental crisis of truly global proportions, every last bit of it attributable to a wildly accelerating human consumption of the planetary habitat, and you have one of the world’s major offenders expressing grave concern that the rate at which it is able to consume might actually drop a notch or two. Think about it. I suggest that this attitude signifies nothing so much as stark, staring madness. It is insane: suicidally, homicidally, ecocidally, omnicidally insane. No, I’m not being rhetorical. I meant what I’ve just said in the most literal way possible,(41) but I don’t want to convey the misimpression that the I see the Japanese as being in this respect unique. Rather, I intend them to serve as merely an illustration of a far broader and quite virulent pathology called “industrialism”—or, lately, “post-industrialism”—a sickness centered in an utterly obsessive drive to dominate and destroy the natural order (words like “production,” “consumption,” “development” and “progress” are mere code words masking this reality).(42)

It’s not only the industrialized countries which are afflicted with this disease. One by-product of the past five centuries of European expansionism and the resulting hegemony of eurocentric ideology is that the latter has been drummed into the consciousness of most peoples to the point where it is now subconsciously internalized. Everywhere, you find people thinking it “natural” to view themselves as the incarnation of god on earth—i.e., “created in the image of God”—and thus duty-bound to “exercise dominion over nature” in order that they can “multiply, grow plentiful, and populate the land” in ever increasing “abundance.”(43)

The legacy of the forced labor of the latifundia and inculcation of Catholicism in Latin America is a tremendous overburden of population devoutly believing that “wealth” can be achieved (or is defined) by having ever more children.(44) The legacy of Mao’s implementation of “reverse technology” policy—the official encouragement of breakneck childbearing rates in his already overpopulated country, solely as a means to deploy massive labor power to offset capitalism’s “technological advantage” in production—resulted in a tripling of China’s population in only two generations.(45) And then there is India…

Make absolutely no mistake about it. The planet was never designed to accommodate five billion human beings, much less the ten billion predicted to be here a mere forty years hence.(46)

If we are to be about turning power relations around between people, and between groups of people, we must also be about turning around the relationship between people and the rest of the natural order. If we don’t, we’ll die out as a species, just like any other species which irrevocably overshoots its habitat. The sheer numbers of humans on this planet needs to come down to about a quarter of what they are today, or maybe less, and the plain fact is that the bulk of these numbers are in the Third World.(47) So, I’ll say this clearly: not only must the birth rate in the Third World come down, but the population levels of Asia, Latin America, and Africa must be reduced over the next few generations. The numbers must start to come down dramatically, beginning right now.

Of course, there’s another dimension to the population issue, one which is in some ways even more important, and I want to get into it in a minute. But first I have to say something else. This is that I don’t want a bunch of Third Worlders jumping up in my face screaming that I’m advocating “genocide.” Get off that bullshit. It’s genocide when some centralized state, or some colonizing power, imposes sterilization or abortion on target groups.(48) It’s not genocide at all when we recognize that we have a problem, and take the logical steps ourselves to solve them. Voluntary sterilization is not a part of genocide. Voluntary abortion is not a part of genocide. And, most importantly, educating ourselves and our respective peoples to bring our birth rates under control through conscious resort to birth control measures is not a part of genocide.(49)

What it is, is part of taking responsibility for ourselves again, of taking responsibility for our destiny and our children’s destiny. It’s about rooting the ghost of the Vatican out of our collective psyches, along with the ghosts of Adam Smith and Karl Marx. It’s about getting back in touch with our own ways, our own traditions, our own knowledge, and it’s long past time we got out of our own way in this respect. We’ve got an awful lot to unlearn, and an awful lot to relearn, not much time in which we can afford the luxury of avoidance, and we need to get on with it.

The other aspect of population I wanted to take up is that there’s another way of counting. One way, the way I just did it, and the way it’s conventionally done, is to simply point to the number of bodies, or “people units.” That’s valid enough as far as it goes, so we need to look at it and act upon what we see, but it doesn’t really go far enough. This brings up the second method, which is to count by differential rates of resource consumption—that is to say, the proportional degree of environmental impact per individual—and to extrapolate that into people units. Using this method, which is actually more accurate in ecological terms, we arrive at conclusions that are a little different than the usual notion that the most overpopulated regions on earth are in the Third World. The average resident of the United States, for example, consumes about thirty times the resources of the average Ugandan or Laotian. Since a lot of poor folk reside in the U.S., this translates into the average yuppie consuming about seventy times the resources of an average Third Worlder.(50)

Returning to the topic at hand, you have to multiply the U.S. population by a factor of thirty—a noticeably higher ratio than either western Europe or Japan—in order to figure out how many Third Worlders it would take to have the same environmental impact. I make that to be 7.5 billion U.S. people units. I think I can thus safely say the most overpopulated portion of the globe is the United States. Either the consumption rates really have to be cut in this country, most especially in the more privileged social sectors, or the number of people must be drastically reduced, or both. I advocate both. How much? That’s a bit subjective, but I’ll tentatively accept the calculations of William Catton, a respected ecological demographer. He was the guy who estimated that North America was thoroughly saturated with humans by 1840.(51) So we need to get both population and consumption levels down to what they were in that year, or preferably a little earlier. Alternatively, we need to bring population down to an even lower level in order to sustain a correspondingly higher level of consumption.

Here’s where I think the reconstitution of indigenous territoriality and sovereignty in the West can be useful with regard to population. Land isn’t just land, you see; it’s also the resources within the land, things like coal, oil, natural gas, uranium, and maybe most important, water. How does that bear on U.S. overpopulation? Simple. Much of the population expansion in this country over the past quarter-century has been into the southwestern desert region. How many people have they got living in the valley down there at Phoenix, a locale that might be reasonably expected to support 500?(52) Look at the sprawl of greater LA: twenty million people where there ought to be maybe a few thousand.(53) How do they accomplish this? Well, for one thing, they’ve diverted the entire Colorado River from its natural purposes. They’re siphoning off the Columbia River and piping it south.(54) They’ve even got a project underway to divert the Yukon River all the way down from Alaska to support southwestern urban growth, and to provide irrigation for the agribusiness in northern Sonora and Chihuahua called for by NAFTA.(55) Whole regions of our ecosphere are being destabilized in the process.

Okay, in the scenario I’ve described, the whole Colorado watershed will be in Indian Country, under Indian control. So will the source of the Columbia. And diversion of the Yukon would have to go right through Indian Country. Now, here’s the deal. No more use of water to fill swimming pools and sprinkle golf courses in Phoenix and LA. No more watering Kentucky bluegrass lawns out on the yucca flats. No more drive-thru car washes in Tucumcari. No more “Big Surf” amusement parks in the middle of the desert. Drinking water and such for the whole population, yes, Indians should deliver that. But water for this other insanity? No way. I guarantee that’ll stop the inflow of population cold. Hell, I’ll guarantee it’ll start a pretty substantial outflow. Most of these folks never wanted to live in the desert anyway. That’s why they keep trying to make it look like Florida (another delicate environment which is buckling under the weight of population increases).(56)

And we can help move things along in other ways as well. Virtually all the electrical power for the southwestern urban sprawls comes from a combination of hydroelectric and coal-fired generation in the Four Corners region. This is smack-dab in the middle of Indian Country, along with all the uranium with which a “friendly atom” alternative might be attempted,(57) and most of the low sulfur coal. Goodbye, the neon glitter of Reno and Las Vegas. Adios to air conditioners in every room. Sorry about your hundred mile expanses of formerly street-lit expressway. Basic needs will be met, and that’s it. Which means we can also start saying goodbye to western rivers being backed up like so many sewage lagoons behind massive dams. The Glen Canyon and Hoover Dams are coming down, boys and girls.(58) And we can begin to experience things like a reduction in the acidity of southwestern rain water as facilities like the Four Corners Power Plant are cut back in generating time, and eventually eliminated altogether.(59)

What I’m saying probably sounds extraordinarily cruel to a lot of people, particularly those imbued with the belief that they hold a “god-given right” to play a round of golf on the well-watered green beneath the imported palm trees outside an air-conditioned casino at the base of the Superstition Mountains. Tough. Those days can be ended with neither hesitation nor apology. A much more legitimate concern rests in the fact that many people who’ve drifted into the Southwest have nowhere else to go to. The places they came from are crammed. In many cases, that’s why they left.(60) To them, I say there’s no need to panic; no one will abruptly pull the plug on you, or leave you to die of thirst. Nothing like that. But quantities of both water and power will be set at minimal levels. In order to have a surplus, you’ll have to bring your number down to a more reasonable level over the next generation or two. As you do so, water and power availability will be steadily reduced, necessitating an ongoing population reduction. Arrival at a genuinely sustainable number of regional residents can thus be phased in over an extended period, several generations, if need be.