7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

From the number-one bestselling author of Maria in the Moon and The Lion Tamer Who Lost comes a sweeping, beautifully written, tender story of love, courage and the power of words… ***Longlisted for the Not the Booker Prize*** 'It's a gentle book, full of emotion and it's similar in tone to The Book Thief, a book that Rose reads with a torch under the bedclothes' Irish Times 'Louise Beech masterfully envelops us in two worlds separated by time yet linked by fierce family devotion, bravery and the triumph of human spirit. Wonderful' Amanda Jennings ______________ All the stories died that morning … until we found the one we'd always known. When nine-year-old Rose is diagnosed with a life-threatening illness, Natalie must use her imagination to keep her daughter alive. They begin dreaming about and seeing a man in a brown suit who feels hauntingly familiar, a man who has something for them. Through the magic of storytelling, Natalie and Rose are transported to the Atlantic Ocean in 1943, to a lifeboat, where an ancestor survived for fifty days before being rescued. Poignant, beautifully written and tenderly told, How To Be Brave weaves together the contemporary story of a mother battling to save her child's life with an extraordinary true account of bravery and a fight for survival in the Second World War. A simply unforgettable debut that celebrates the power of words, the redemptive energy of a mother's love … and what it really means to be brave. ______________ 'An amazing story of hope and survival … a love letter to the power of books and stories' Nick Quantrill 'Two family stories of loss and redemption intertwine in a painfully beautiful narrative. This book grabbed me right around my heart and didn't let go' Cassandra Parkin 'Louise Beech is a natural born storyteller and this is a wonderful story' Russ Litten 'Beautifully written, intelligent and moving, this book will stay with you long after you reach the end' Ruth Dugdall

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 505

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Praise for Louise Beech

‘Wow! The Mountain in my Shoe has a gentle start but my goodness it packs a punch. I was in tears at the end … a moving and powerful book’ Jane Lythell, author of Woman of the Hour

“Louise Beech's characters jump off the page with their unique and utterly convincing voices … a rich, psychologically profound novel about overcoming adversity and finding our own strength, and I'll be mighty surprised if it doesn't fly straight into the bestseller lists. It’s a masterpiece’ Gill Paul, author of The Secret Wife

‘Louise Beech proves with this incredibly moving story that the success of her debut How To Be Brave – a 2015 Guardian Readers’ Pick – was no flash in the pan. This is a novel that tugs at the soul – it’s about the importance of family, of a proper home, and the fact that even the darkest of characters have some good in them, somewhere. A fabulous, exquisitely written novel which will stay with you for a long time after you turn the final page’ David Young, author of Stasi Child

‘Louise Beech's excellent debut was an examination of what it means to be brave. In her second novel, The Mountain In My Shoe, Beech revisits this topic, this time tackling the dark and difficult subjects of abandonment and abuse. This is a wonderful, nuanced book, which while probing the damage wreaked by absence and neglect, also explores the power of love and hope, the redemptive possibilities of family and friendship and what it means to be truly “home”. It made me laugh and cry by turns. I loved it’ Melissa Bailey, author of Beyond the Sea

‘This gripping story is the kind of book to put your life on hold for. The book is full of beautiful descriptions, images and observations, and is hauntingly poignant, while also managing to keep a relentless tension and pace. It is a book about people trying to do the right thing in the hardest of circumstances, about loss, about love and about being brave even when all hope is gone. I was in floods of tears by the end and know that the characters will stay with me for a very long time. A worthy successor to the brilliant How To Be Brave, and I don't say that lightly. Read it’ Katie Marsh, author of A Life Without You

‘The Mountain in My Shoe is a different kind of book, but it does have echoes of the author’s debut in that it is about the relationship between a child with needs and an adult who also needs mending. It is cleverly laced with a chilling and gripping storyline about a controlling, possibly psychotic husband. I couldn’t put it down. Louise Beech is an author who writers with her heart on her sleeve’ Fleur Smithwick, author of One Little Mistake

‘You know when you love a book so much that you don't want it to end – yet you are compelled to keep on reading? And you know when you find a book that you'll read again and again? Well, The Mountain in My Shoe is definitely one of those books for me … This is a fascinating page turner that wrenches at your insides. It's dark, compelling and highly thought-provoking and left me with tears rolling down my cheeks. The story and characters will linger on long after you've finished reading the final page’ Off-the-Shelf Books

‘Beech employs a touch of magic as the suffering Colin and the frightened Rose reach across the years to help each other to be brave, but the author is at her best when she’s describing the agonies of the shipwrecked men drifting on the empty sea. It’s a gentle book, full of emotion, suitable for young readers, and it’s similar in tone to The Book Thief, a book that Rose reads with a torch under the bedclothes’ Irish Times

‘It is a brilliantly creative work of fiction, and a beautiful thank-you letter to the magic of stories and storytelling’ Anna James, We Love this Book

‘This book tells the story of Rose and her mother, Natalie, who are trying to cope with Rose’s newly diagnosed, and very serious, illness. With the help of a diary she discovers, Natalie begins to tell Rose the tale of a group of men battling to survive on the Atlantic ocean in a lifeboat with limited food and water. This is a moving and richly drawn novel, and fine storytelling in its purest form. With lilting, rhythmic prose that never falters How To Be Brave held me from its opening lines. I found myself as eager to return to the story of Colin, Ken and their companions on their boat in 1943 as Rose herself was! Louise Beech masterfully envelops us in two worlds separated by time yet linked by fierce family devotion, bravery and the triumph of human spirit. Wonderful’ Amanda Jennings, author of In Her Wake

‘One of the books that has really struck a chord with us this year is How to be Brave by Louise Beech. It is truly 5*, uplifting and compelling. This is a haunting, beautifully written, tenderly told story that wonderfully weaves together a contemporary story of a mother battling to save her child’s life through the medium storytelling with an extraordinary story of bravery and a fight for survival in the Second World War’ Trip Fiction

‘A wholly engrossing read, How To Be Brave balances its two storylines with a delicate precision. I loved the dynamic between Natalie and Rose, and Beech manages to convey an awful lot about Rose's condition without ever setting foot in dreaded info-dump territory. The epic survival strand, as the shipwrecked sailors fight against the odds, is engrossing, and the connections are seamless. Bravo!’ Sarah Jasmon, author of The Summer of Secrets

‘A beautiful story full of love, courage and spirit … Louise Beech has cleverly interwoven past and present to produce a brilliant debut novel that explores bravery and endurance on many different levels. I was captivated from the very beginning…’ Katy Hogan, author of Out of the Darkness

‘Beautifully written, intelligent and moving, this book will stay with you long after you reach the end’ Ruth Dugdall

‘Two family stories of loss and redemption intertwine in a painfully beautiful narrative. This book grabbed me right around my heart and didn’t let go’ Cassandra Parkin

‘An amazing story of hope and survival … a love letter to the power of books and stories’ Nick Quantrill

‘Louise Beech is a natural born storyteller and this is a wonderful story’ Russ Litten

‘This is a yellow brick road of a novel that when it delivers you home will have you seeing all the people you care about anew, in glorious Technicolour. The stories are authentically told, in fact they are rooted in the author’s family history, and the characters are so real that they speak to anyone who knows what it is to be alone and what it means to be connected to others. How To Be Brave shares the same magic that Ray Kinsella’s Field of Dreams possessed. It makes you want to snuggle up with your own children in a book nook and hold them close’ Live Many Lives

‘The two threads of the story are cleverly interwoven, the historical aspects are stunningly intuitive and with a highly engaging sense of place and time – a novel of two intensely emotional halves creating an incredible whole. It is emotionally resonant – you will cry – but it is also brave, true and utterly compelling, a cliff’s edge read where you are waiting for that moment then realise that the whole darn thing is THAT moment’ Liz Loves Books

‘Exquisitely written with storytelling of pure beauty, this debut novel is like nothing I’ve read before. Highly engaging and compelling, Louise’s writing is sharp and astute, wise to the emotions built through a mother-daughter relationship. How To Be Brave is a truly unforgettable novel. An extraordinary debut – emotionally driven, finely written and highly compelling’ Reviewed the Book

‘Every so often a book will come along and will seep its way into your heart right from the very beginning. You’ll instantly connect with the main protagonists and it will leave you feeling completely overwhelmed by how much it has affected you. This was the effect that How To Be Brave had on me’ Segnalibro

‘Wow, I have just this minute finished How to be Brave and I am just in an emotional state trying to process and express how much I loved this book, which is definitely a contender for my Book of the Year even in September! Even if you have to beg, steal or borrow, read this book – it is truly spectacular’ Louise Wykes

‘Ms Beech has written an amazing story. A story of survival, of struggle, of bravery and hope. But mostly, it is a story of unconditional love, the best cure for every pain and disease … I hope that this books won’t stand alone on Ms Beech’s bookshelf, there will be many more from her writing pen in future’ Chick Cat Library Cat

‘The writing is simply beautiful – quite effortless prose, full of emotion, totally engrossing whichever strand of the story you may be immersed in. The relationships are perfectly drawn … It’s a wonderful story about what bravery really is, the power of words and stories, full of immense sadness, but full of hope and suffused with love. I was absolutely enthralled by this book from beginning to end, with scenes that will stay in my memory for a very long time – whether it’s Rose injecting her bruised flesh, Natalie and her mallet, the lead shark following Colin’s lifeboat, or the simple reading of the daily prayer. Quite wonderful’ Being Anne Reading

‘With a hint of ghost story, mixed up with contemporary, up to the minute narrative and a good dose of wartime history, How To Be Brave is a very special, unique and quite beautiful story. The stories are blended to perfection, the author masterfully and seamlessly knits them together resulting in a hugely satisfying, intelligent and emotional creation’ Random Things through my Letterbox

‘Prepare for tissues. You would never think that a story of illness merged with a story of sailors abandoned at sea would work but this does and more. Remarkable. The power of stories really can change the world’ The Booktrail

‘Beautifully written … This exceeded my expectations and was a deeply touching read about a mother’s love, family history and above all bravery’ Charlene Jess

‘It is intriguing, deftly crafted and captivating. Not only that, but here is a story about stories which bears testament to the transformative power of stories. I have a feeling that I have not read this book for the last time’ Richard Littledale, author of The Littlest Star

‘The reader lives the ordeals of the child, the mother while witnessing the horrors of the relentless 50 days’ battle in the sea. There are mystic elements of the metaphysical is this book too, especially Beech’s writing of how Colin, the grandfather long gone, reaches out from beyond. This is a book that could easy have fallen into slush sentimentality or even elements of the ridiculous. It avoids these traps beautifully with simple, effective and beautifully descriptive prose’ Brian Lavery

‘Louise has crafted a beautifully written novel using her grandfather Colin’s story and her own personal experience with her daughter’s illness. An absolute joy to read … Louise is a natural storyteller’ My Reading Corner

‘This is a story woven from the author’s personal experience and is one of hope despite devastating challenges. It matters little if Colin actually appeared to them; his story inspired and it is that which was needed at such a difficult time. The initial build-up set a scene necessary for understanding; when finished a powerful story lingers.’ Jackie Law, Never Imitate

‘It’s not enough that the story is (almost) true though. It’s also beautifully, poetically written’ Louise Reviews

‘Rarely has a book touched me the way that How To Be Brave has. Louise Beech has written a debut novel that will live long in this reviewer’s memory and for those who have read it, for those who are going to read this and I urge you to do just that, your heart will be taken by the sheer natural brilliance of the writing’ Last Word Reviews

‘I adored this novel. I don’t think I’ve cried so much over a book since reading Charlotte’s Web, when I was about six years old! How To Be Brave will definitely be one of my top ten books of the year. It’s a hard act to follow’ Book Likes

‘The writing is incredibly evocative, I felt like I was sitting alongside Rose and Natalie’s relative. I could feel the boat rising and falling on the waves, taste the thick flesh of the all too rare raw fish on my thickened thirsty tongue and feel the intense heat of the sun as I lay exposed to the elements with the other crew members, as they grew weaker with each passing day’ Pam Reader

‘This book made me cry – for the right reasons. A triumph of love and hope over adversity, of knowing that “ we don’t get less scared, we just find it easier to admit it when we have been as brave as we can”’ Thinking of You and Me

‘How To Be Brave is a heartwarming and heart-wrenching story all mixed in together … beautiful storytelling; it’s amazing that this is the author’s debut!’ Claire Knight

‘How To Be Brave tackles the subject of grief and hardship in such a wonderfully unique way. Each word feels magical and makes the story more captivating. Even in describing something ugly, Louise manages to use such beautiful, captivating language. For example: “One wound cut his face almost in two, like a forward slash dividing lines of poetry.” This kind of writing appears throughout the book and adds to that bittersweet undercurrent that runs throughout. Louise couldn’t have written a more perfect debut novel’ Words Are My Craft

‘I think it’s impossible to encounter this story without being affected by it. I’m finding it difficult to convey how fabulous the writing is – as Louise Beech has left me, to quote her, “speechless, full of silent words” and not a few tears’ Linda’s Book Bag

‘Stunning, penetrating’ The Discerning Reader

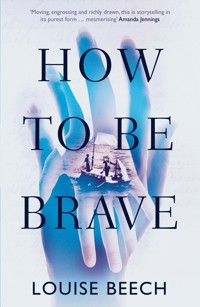

‘I will start by saying everything about this book is absolutely beautiful. Initially I was drawn in by the distinctive and quite stunning visual on the cover. I was also fascinated by the outline of the story and wondered how it was possible to merge the past with the present. Rest assured it works, it really, really works’ Reflections of a Reader

‘How To Be Brave is an eye-opening book, which is beautifully written. It’s one of those novels where the characters will stay with you long after you have finished reading it. A highly recommended read’ Sarah Hardy

‘How To Brave is two wonderful stories wrapped into one compelling read. Louise Beech is adept at both narratives and styles and writes with a confidence and trueness of voice that can only come from experience and yet manages to turn what must have been a truly testing time in her life into a great, gripping, moving and thoroughly rewarding read for all’ Mumbling about Music

Contents

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Louise Beech has always been haunted by the sea, and regularly writes travel pieces for the Hull Daily Mail, where she was a columnist for ten years. Her short fiction has won the Glass Woman Prize, the Eric Hoffer Award for Prose, and the Aesthetica Creative Works competition, as well as shortlisting for the Bridport Prize twice and being published in a variety of UK magazines. Louise lives with her husband and children on the outskirts of Hull – the UK’s 2017 City of Culture - and loves her job as a Front of House Usher at Hull Truck Theatre, where her first play was performed in 2012. She is also part of the Mums’ Army on Lizzie and Carl’s BBC Radio Humberside Breakfast Show. This is her first book.

This is dedicated to Colin’s children, grandchildren, great grandchildren, and many nieces and nephews. He must be up there – with his brothers Alf, Stan, Gordon and Eric, and wife Kathleen – smiling down on us all.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Truth inspires all stories. A memoir is a true account of the author’s experience. A biography is a true account of another person’s life. A novel is fiction but it dares to explore the truth more deeply than any other form.

This book is all of the above. Rose and Natalie are based on my own time with a newly diabetic child. The lifeboat story of my grandfather, Colin Armitage, took place in 1943, mostly as is described here. But it was my imagination – merged with memories, newspaper articles, letters, and family accounts – that brought these stories to life.

Sometimes all we can ever know is what probably happened, and that is the truth.

‘The sea has neither meaning nor pity’

Anton Chekhov

1

A SORT OF RECOVERY POSITION

Still two of us left but we are getting very weak. Can’t stand up now. We will stick it to the end.

K.C.’s log

There were two of us that night.

Outside, the autumn dark whispered to me. Halloween’s here already, it said. The pumpkins are glowing, smell the whiff of old leaves, of bonfires coming, of changes, of winter, of endings. But I wasn’t listening because inside the house my daughter Rose was whispering aloud the words in my current paperback, slowly forming each vowel and consonant as she kicked my kitchen cupboard and twirled her hair about her finger.

‘“Vases of jasmine and…”’ she began. ‘How do you say that? “Vases of jasmine and s-t-a-r-g-a-z-e-r lilies barely dispel the urine aroma” … urine, is that wee? “Framed pictures of cities accen– How do you say that? A-c-c-e-n-t-u-a-t-e…”’

‘Don’t read that,’ I snapped, taking the book from Rose and putting it in the drawer. ‘It’s not suitable for nine-year-olds. It’s got bad words in it.’ To myself I said, ‘Plus it’s not very good.’

‘So why are you reading it?’

‘I’m not. I’m going to give it to the charity shop.’

Rose opened and shut the drawer, over and over, until I stopped her. She was wearing a cat costume, with silky velvet gloves and ears, pencil whiskers and a smudge of black polish on her nose. ‘You always think I’m stupid,’ she said.

‘I don’t. You’re not.’

‘I understand adult books, you know,’ she pouted. ‘I read Jane Eyre. I can do all the words.’

‘I’m sure you can.’

‘And you say bad words all the time.’

I couldn’t argue with that.

She slammed the drawer one last time. ‘I’m thirsty,’ she said.

‘You know where the tap is.’

I was grumpy from spending three hours gutting and carving a face into a lopsided pumpkin. Rose had wanted to make a Despicable Me minion, but I’d insisted I hadn’t the skill. She hadn’t argued, so I’d gone ahead and cut a grinning face, all wonky, with one eye bigger than the other. I swore when I cut the end of my finger, and Rose had said language and told me I was a wuss. The blood dripped onto our pumpkin, leaving him with two lines of auburn hair.

‘The words were jumping,’ Rose said, gasping from having downed the glass of water in one go.

‘What words?’

‘The bad ones in your book.’ She kicked at the kitchen cupboard. Charcoal leggings had ridden up her legs, exposing matchstick ankles. When had they got so thin? Her reddish blonde hair needed washing but I didn’t want her going out in the chill air with damp curls.

‘Don’t kick my doors,’ I said.

‘Bad words, swearwords, bad words, bastards.’

‘Rose!’ I touched her clammy forehead. ‘Are you feeling okay? You must eat something if you’re going out trick-or-treating with Hannah and Jade. What do you want? Beans on toast?’

‘Swearwords,’ Rose said defiantly, and pushed me away.

I rummaged in the fridge for something that might tempt her to eat, and perhaps behave better. Cold noodles, some tuna, half a tin of beans, custard. That would do it; the magic of cake and custard.

When I turned, the world had changed. It was quiet, slow. There were no whispers, no bad words or swearwords, only Rose falling, her mouth moving, as if she were reading in our book nook. I couldn’t hear the swirl of syllables, yet something in their rhythm gave me déjà vu. I tried to read her lips; What are you telling me? I wanted to scream.

But I was silent as I watched her fall – down, down, down – and I couldn’t move. Couldn’t save her.

When her head hit the tiles with a thick crack the spell broke too. I dropped the bowl of custard and ran to her. I shook her limp shoulders and called ‘Rose, Rose, Rose’ – not what you’re supposed to do in an emergency, no sort of recovery position or mouth-to-mouth wake-up kiss, just what comes naturally when you want your child back.

‘Jake,’ I cried. ‘Help me!’ But of course he was far away and wouldn’t be back for months. ‘Help me!’ I screamed into the night. ‘Somebody – help me!’

The candle in our skewed, grinning pumpkin danced as though mocking Rose’s lifelessness – but where had the draught come from? I felt it on my face too. Had a door opened somewhere? Had someone heard me?

‘Who’s there?’ I called.

But no one answered; it was just us.

And then we were surrounded by the smell of the sea – salty, potent, fresh. I’d been smelling it randomly for days. We live on the Humber Estuary but we’re still twenty-five miles inland; yet somehow it had found me; the sea. I’d been getting out of bed at dawn and a briny breeze would greet me, as though wafting up from the bedclothes. I’d hang out wet clothes and it would float down from the trees, the clouds, somewhere.

It faded. So I sniffed Rose’s cheek.

I found comfort in her powerful perfume; it calmed my panic a little. Often when she joins me on the sofa for a film I deeply inhale the top of her head, absorbing the hint of school classrooms and sleep and breath. She asks why and shoos me off, but I can’t resist. Smelling a new baby is the next thing you do after studying them; so as Rose lay on the floor by the washing machine I breathed in her scent as though it would sustain me through what might come.

Then I dialled 999 and we waited.

An ambulance siren heralded two paramedics. All I can remember about them is that they were male. They came into the kitchen and bent down to check Rose and asked questions and made smudgy footprints like preschool paintings and listened to her heart and took her pulse. We must have looked a curious picture in our Halloween costumes, me wearing a pale-blue nurse’s dress stained with beetroot juice and Rose in her black cat suit.

They asked more questions.

So I told them in a tumble of words, ‘One minute we were making our pumpkin and then she was talking about naughty words in my book and then I looked for custard and then suddenly she went down, cold. She plays tricks on me all the time, but this wasn’t mischief.’

The paramedics gently lifted Rose onto a stretcher, covered her with a red blanket and wheeled her to the ambulance. I followed. Our neighbour, April, came up the path with what looked like a severed head in her hand – ‘a pumpkin,’ my future, looking-back self would say, ‘it was Halloween, remember, and you were going to let Rose go with her friends to the town square, carrying skeleton bags to beg for sweets, you made them promise to stay together.’

I noticed our rhododendron bush needed trimming but remembered the shears were broken; the thought came and went like a rescue flare at sea, flashing and then dying. I climbed into the ambulance after Rose. April was still on our path, so I smiled at her, and was not sure why. Perhaps it was to say I was fine, we were fine, it would all be fine. One of her fingers was hooked through the pumpkin’s cut-out eye.

I didn’t hear the ambulance engine rev up or the doors close or the sirens start, but I do now, long afterwards, when I think of it in the dark. The world lost its sound again and it was just us two.

I removed Rose’s glove and held a cool hand in mine. It fit perfectly, like they were two warped jigsaw pieces that make sense when joined. I studied her fine lines and traced the scar from when she fell off the shed roof and pressed my nose against her skin. She wouldn’t let me hold her hand anymore, and a part of me was glad of unconsciousness, of the chance to kiss it like I had when she was first born.

Then I’d willed her small fingers to be kind, to be gifted, to be brave. To hold a pen or guitar or paintbrush. Now I willed them to ball into fists and push me away – to wake up.

At Accident and Emergency I had to let go and Rose was wheeled straight to a private bed area, black tail dangling from the trolley. I hovered by the curtain, not wanting to be a bother. My relief that these medics acted so quickly and knew what to do and did it without pause kept me from absolute panic; alarm at why they needed to never surfaced.

A nurse called Gill took me aside, asking for details and if she could call anyone. Her untidy red hair suggested a long shift. I managed to give our names and tell her there wasn’t anyone near enough that I wanted.

‘Has Rose had any symptoms?’ she asked.

In the din I thought for a second she’d asked if Rose had had any sympathies and felt a curious guilt that I apparently had none.

‘She’s only nine,’ I said.

‘Yes – they’re going to look after her. I just need to ask how she’s been in the last few weeks. What kind of…’

And I understood my mistake. ‘Thirst,’ I said.

‘Drinking lots?’ asked Gill.

I nodded. ‘Oh, lots.’

The thirst came first, beginning softly, like a spring shower and building into a force-ten gale. It had all started when Jake left so I’d thought it was psychosomatic or that Rose was seeking attention. I’d brushed off her grumbles at first, suggested she carry a bottle of water with her.

One night she had come to my too-empty bed; I woke to her ghostly presence, standing at my side. She said afterwards that I was always far crabbier than her dad when disturbed and this had made her watch me for ten minutes until I stirred.

‘I’m thirsty,’ she said.

‘What?’

I didn’t turn the light on; when she was a baby I always fed her without one during the night, knowing we’d both stay sleepy that way. It worked and she had been a settled infant. People called me lucky, but I’m just practical. And I like the dark – it’s safe.

‘I’m thirsty,’ Rose repeated, her tone mimicking mine when I feign patience.

‘Get a drink then,’ I said. ‘You don’t have to ask for a drink.’

‘I don’t think a drink will work.’ Even in the dark I knew the corner of her lip was curling up like old paper.

‘Rose, it’s late. Shit, I have to get up early.’

‘Language.’

‘I’m allowed to swear when I’m disturbed.’

‘Mum, this thirst, it’s different. Like it’s also hunger.’

I sat up. Tried to be kind. ‘Maybe you’re dreaming. Maybe go back to sleep and you’ll wake up fine.’

‘No, mum, I won’t. I had it yesterday and the one before that and it’s totally not going. It’s getting bigger.’

I smiled at her childlike description, left the bed’s warmth and put an arm about my daughter’s slight frame. She put her damp head to my shoulder – a place she now reached easily – and her forehead smelt of gravy and her hair tickled my cheek like shampooed spiders and she cried softly, as if I wasn’t even there; as if she were resigned to this everlasting thirst; as if she were whispering to someone far away, from long ago.

We went to the kitchen and I watched her messily glug two glasses of juice, realising she had a book under her arm. Always a book – even in sleep. She’d probably dozed off with a finger between chapters and not let go.

I walked Rose back to bed, covered her up and said, ‘Sleep now.’

‘Still thirsty,’ she muttered, but snuggled down.

‘Stress can do that,’ I said, sudden realisation causing the words to jump from my mouth without analysis. Then, more to myself, I added, ‘Anxiety can make your mouth dry so you think you’re thirsty. I had it when … well, when I was anxious.’ Remembering Rose was there I asked, ‘What’s making you worry?’ It was a stupid question, the kind a stupid mother asks of a child whose father has been away for a month. But she was asleep.

Like now.

Gill the nurse listened to my descriptions of excessive juice drinking, resultant frequent toilet visiting and disturbed nights without interrupting me, but with an expression I couldn’t at first decipher. When I finished I realised she was anticipating everything I’d said.

‘I’ve a strong suspicion what caused Rose to collapse,’ she said. ‘It’ll just take a simple blood test to diagnose.’

‘Really?’

She nodded. ‘Why don’t you take a seat and we’ll test her now. Then we can either eliminate it or know what we’re dealing with. Treatment is simple if we diagnose her.’

I looked over at the bed – Rose, still in her cat costume, looked too small; almost weightless, as though the mattress had swallowed her. When had she shrunk? Was it baby fat she’d lost? Had she lost it because her father was away? Was it the insatiable thirst and constant hunger and excessive napping after school and at the weekend? Or was it me?

‘Her dad went to Afghanistan four weeks ago,’ I said to Gill. ‘Is that why?’

‘No, no, this condition – well, it happens out of the blue. It’s no one’s fault, I assure you.’

I frowned. ‘You sound so sure she has … what is it you think she has?’

‘Let’s just do the blood test first. Would you like a cup of tea?’

I shook my head. Gill walked away; the back of her dress had creased in a lightning shape.

I sat on a plastic seat between a boy whose nose was split wide, like the pumpkin on our kitchen worktop, and a woman with stitches over her cheek. The automatic doors opened and closed, over and over, admitting the casualties of Halloween.

An old man with a face like crepe paper said to me as he got wheeled past, ‘They should all wear short dresses like yours, it’d keep me happy. But not the blood – it’s like we’re at war again!’

I remembered I was dressed as a zombie nurse, my skirt considerably shorter than the staff’s, the fabric made bloody with juice, and my skin whitened with face paint and streaked with crimson lipstick.

I remembered also the candle at home, inside the pumpkin. Had I blown it out? No, I didn’t think so. Damn. Would the flame burn through the pumpkin flesh? I should call Jake and tell him to do it.

Of course – he wasn’t there. If he were, he’d have been here with us. I thought of calling April, but who has their neighbour’s phone number on speed dial? She was pleasant enough and we kept an eye on one another’s homes when we were away, but I don’t feel I have to befriend people whose only similarity to me is where we live.

I worried about the candle. It saved me thinking about Rose. I closed my eyes a moment to shut out the busy waiting area but couldn’t block the noise of doors and trolleys and chatter. Rose would want a book when she woke. She’d search under the pillow, be distressed without it.

I covered my ears and put my chin to my chest; a sort of recovery position. In my head was the sea, swishing and swirling and swilling over bleak stony thoughts. I could smell it again, even here amidst injury and pain.

A hand gently touched my shoulder, and I looked up with a start, expecting to see Gill. Instead I looked into dark eyes; in their mirror I saw the ocean I’d heard in my head and a shape like a tattered boat sail and my own face, but drained of colour, as though I were viewing the images through a black-and-white filter.

I readjusted my focus and took in the whole face. He wore his hair like men in the forties did– swept to one side with gluey pomade and cut short around the ear. A suit with thick lapels kept together by four buttons forming a square was worn over a hand-knitted jumper and striped tie. Two polished medals were pinned to his chest. It was a wartime Halloween costume so authentic he must have borrowed it from an older relative.

‘It won’t be long,’ he said.

He looked a bit like my grandad, seen in old photos. When I was a child, family members used to talk about him. Said he was brave, that he had been awarded medals, and that there was a museum in London with his things in it. Thinking about him used to keep me awake at night – or did it wake me up? I’d hear the sea then, too, and strange voices and accents. I’d smell salt and think he was there at the end of my bed, telling me stories. I never met him properly, not in the flesh. He died long before I even existed. I hadn’t thought about him in a long time. Adult life tends to do that – eat up your thinking time, kill your dreams.

‘You mustn’t be scared,’ the stranger said.

‘I’m not,’ I lied. ‘You know, you look like … well, someone I’ve only seen pictures of. But it’s weird, you’re exactly how I’d imagine him if he were alive.’ I shrugged, realised I was babbling. ‘Your costume’s too nice for Halloween. The kids won’t know what it is. They’re all into wizards.’ I paused. ‘I hate hospitals.’

‘Should be grateful for them.’ His accent was beautifully rich Yorkshire, familiar in its flow, like mine only somehow from a time gone by. ‘I’ve a lot to thank hospitals for.’

‘No, I hate what they mean. You know, if you’re in one it’s not good. My little girl … she … God …’ I couldn’t say anymore.

‘She’s going to be fine.’

‘How can you know that? You can’t possibly. It’s not normal for a nine-year-old to just collapse, is it? And I should’ve seen it coming! What kind of mother am I? I should’ve taken the thirst more seriously. Should’ve had her at the doctor weeks ago. I thought she was just missing her dad.’

My words ran out and I stopped. Tears built behind my eyes like froth on coke poured too fast – but I wouldn’t surrender. If I did I’d be no good to Rose. I tried to apologise for ranting.

‘Do you miss her dad too?’ The sort-of-familiar stranger held my gaze with what I could only call affection. He seemed too interested in my answer for someone I’d never met before. And yet I didn’t mind. In his presence I felt calm and able to be honest. Safe, like in the dark.

‘I do,’ I said softly. ‘He’s been away before but not to a place like that. People say you get used to it – their absence. But this time it feels like he’s missing rather than gone. Does that make sense?’

He nodded. ‘I was missing once – for two months.’

‘You were? Did you get to say goodbye?’

‘I couldn’t.’

He looked down at his palms. I studied them as I had Rose’s earlier; they were crisscrossed like an old map, the hands of a labourer, a man who works for a living. I wanted to put one of mine over his, but that would have been forward, and not me.

‘Why not?’ I asked.

‘There wasn’t time.’

‘Jake had time,’ I said, almost to myself. ‘The night before he left we sat for hours in front of the TV and he was distant. He’s a quiet man in general – you know, polite, affable, but not outgoing. If you talk to him he’ll talk back but he’ll not seek company particularly. I always thought it odd that he joined the forces – but then he has other qualities perfect for such a life: he’s loyal and patient and hardworking. Anyway, we sat that last evening, quietly, until I swore – I’m so bad for it – and I said it was going to hurt enough, him being in a dangerous place, so at least let me have a nice goodbye to remember. And then … he … well, you know …’ I shook my head. ‘Sorry, you don’t want to listen to all this.’ I paused. ‘Who are you with?’

‘My great granddaughter,’ he said.

I frowned. Even at a push he looked no older than thirty. ‘You must mean your daughter?’

‘Mrs Scott?’ It was Gill. Where had she come from?

‘I’ll go and blow that candle out,’ whispered the man, so close to my ear that bristly hair tickled me and I smelt tobacco and the kind of aftershave that older men favour.

‘Beg your pardon?’ I turned to look at him, but he’d gone. How so fast?

I stood, frowned at Gill, and pushed past her to look up the corridor. Porters and nurses and patients and family members filled every space, some sat, some stood by the vending machine, some hurried, some pushed trolleys or wheelchairs. I searched for that mud-brown jacket, for the slick head of dark hair. Even without seeing him I knew somehow that he’d have walked with a merry, must-get-there swing, hands in pockets, and that he’d be whistling a tune I’d know but not be able to name.

‘Where did he go?’ I asked Gill.

‘Who?’

‘The man in the brown suit. He was just here.’

Gill frowned. ‘I didn’t see anyone like that.’

I looked at the boy with the nose and the woman with stitches across her cheek and my empty chair. If they were still there, with me in the middle, how had he sat next to me?

‘We should sit down,’ said Gill.

‘I don’t want to,’ I said. ‘I’d rather stand.’

I wasn’t sure why, but a curious line came into my head – We’ll do it together. We’ll be standing when she meets us, by God we will.

Gill interrupted with, ‘I really think we should…’

‘No. Just tell me.’

‘We did the test.’

I nodded.

‘There’s no need to be too alarmed as this condition is manageable,’ she said, as she must have done many times over to various worried parents. ‘We tested Rose’s blood and found an excessively high sugar content, over thirty-eight millimoles. I understand this will mean little to you right now, but, well, you’ll understand it in time. And this reading means your daughter has insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, or as we generally call it, Type 1 diabetes.’

‘Diabetes?’ I frowned. ‘But … she isn’t fat. There’s nothing on her.’

‘Not all diabetes is weight-related and Type 1 is completely unrelated to lifestyle. No one really knows its cause. For whatever reason the body attacks the pancreas and it stops producing insulin. There are theories that it might be inherited, but we think it requires some sort of environmental trigger. Maybe an infection or virus or stress.’

‘Inherited? But I don’t think anyone …’

‘It’s not always inherited.’ She put a hand on my arm. ‘Don’t think too hard about the whys and hows. You’ll drive yourself up the wall. Really this is a good thing to diagnose because it means Rose will be fine.’

‘Diabetes,’ I repeated, as though testing the strength of the word. Maybe if I said it enough it would make sense, sink in.

‘Yes,’ said Gill. ‘It’ll surprise you how fast she’ll be herself again once we set up an insulin drip. By tomorrow she’ll be alert, probably starving hungry. You’ll be able to go home in a few days and give her the insulin yourself.’

‘Insulin? What, all the time?’

‘Yes, she’ll need it for the rest of her life.’

‘And how will she take this insulin at home? Pills? She’s a bugger for not being able to swallow them. I have to buy liquid paracetamol.’

‘No, not pills. Injections.’

‘Injections?’ I tried to imagine it and couldn’t.

Instead I thought of when Rose went away with her grandma for a week and I had missed her smell. I still had Piglet, her favourite toy as an infant, which I’d kept in the vain hope of retaining that baby scent. But the fragrance had gone and it smelt like the inside of a stale box. I searched for remnants of other, still-smelly toys and rags. Eventually I resorted to Rose’s pillowcase and there it was; the subtle essence of my child. Other kids smell alien, but our own babies produce a unique scent that we find irresistible. No sooner have they left the womb than they apologise for all the pain they’ve caused by seducing us with their odour.

I wondered if insulin wouldn’t ruin Rose’s sweet smell. I wanted Jake, realising it suddenly, like when you remember you’ve left a candle burning. It wasn’t fair that I was alone, dealing with this. I feared sometimes that the longer he was away, the less I’d love him, that loneliness would replace my heart.

How would I do injections on my own? Jake would have to be told. Could he come home? Would they let him leave a warzone? I shook my head and refused to look at Gill.

‘She can’t have injections,’ I said. ‘She’s stick thin, tiny. I can’t put a needle into that baby skin.’

‘Let’s go into this cubicle, where it’s more private.’ Gill guided me and I let her, mental resistance to the news sapping all my physical strength. ‘It will become part of life, I promise you.’

‘But it won’t be the same will it?’

‘No, but I know many nine-year-olds who cope very well with the finger prick tests, injections and everything.’

‘She shouldn’t have to cope. She’s a baby.’

‘Let me get you a cup of tea. They’ll get Rose settled on the ward and you can stay with her overnight if you want. A specialist diabetes nurse will come and explain it all to you in the morning.’

I surrendered to the news. No more words. No more arguing. A silent world again.

I let myself be taken to where Rose slept. I nodded as various consultants told me things I knew would matter tomorrow and a nurse asked if anyone could bring me a change of clothes.

And then it was just us again, in a sterile room with tan curtains that reminded me of school halls, and an empty handwash machine and a window that looked onto another identical room, except it was the opposite way around, like a mirror image. In that room an exhausted mother in a ridiculous stained dress and flour-white make-up didn’t lean over the bed of a tiny black cat and smell its cheek. No one in that room felt overwhelming guilt and wanted to take the clock off the wall and wind it back so she could be a better mum.

I pulled up the plastic chair that would be bed for the night, put my head on Rose’s tummy and held her free hand. The other one had a tube in it and a nametag about the wrist, like when she was born. I knew if she were merely sleeping she’d reach under her pillow, check her book was there.

But she didn’t.

‘I’ll go and get one before you wake,’ I promised. ‘Whichever you’ve got under your pillow at home.’ I paused. ‘And you can read any of the books on my shelf. Well, maybe not the ones with the really bad words in. Look, we’ll see. But just please wake up and you can read anything you want to.’

Eventually I fell asleep; but on the threshold of a troubled slumber, the image of the medal-wearing familiar stranger blowing out our pumpkin candle appeared in my head; and within the fug of exhaustion and confusion I realised what Rose had been saying as she collapsed on the kitchen tiles:

He’ll get the candle.

2

THE PUMPKINS ARE SLEEPING

We are about 800 miles from land, so will try to make it. Expect rescue anytime now.

K.C.

All through the night ghosts visited: pastel nurses in creased uniforms crept into our room and pricked Rose’s finger end to harvest her blood, on the hour, every hour, over and over. The digits on their tiny machines meant nothing to me and the jargon on her chart could have been Russian for all I understood it.

I woke repeatedly at each of these disruptions, while my skinny cat remained unconscious. And then, before daylight washed over the rooftops like incoming tide, I woke fully. My neck was stiff and Rose’s hand still curled inside mine.

Our pumpkin candle had haunted my half-dreams. How curious that I had imagined a stranger saying he would blow it out and then heard the same words from my fainting daughter’s mouth. Was it possible that someone imaginary might extinguish a flame? What if it wasn’t and I returned to a blackened building? How would I tell Jake that not only was Rose diabetic but our house was gone?

I had to check.

Besides, I didn’t want Rose waking up without a book. She loved them. It had been one of her first words; ‘Book, book, want book, like book.’ Jake had been delighted that our daughter craved literary sustenance over endless Disney movies. I’d suggested it was because I’d read aloud to her while pregnant because it was meant to encourage early language development. I hadn’t wanted Rose to fail at school like I had. I’d also worried her interest might pass.

But she continued to prefer hearing stories read aloud to watching cartoons, nodding with excitement and trying to turn the pages as we went. The sentences I self-consciously pronounced must have evoked images that were better than an animated screen.

Now I whispered a true story in Rose’s ear; ‘I won’t be long, I’ll just put some more sensible clothes on, ring Dad, and bring your things.’

Then I told one of the nurses I’d be back soon and called a taxi.

Outside, the dark again whispered to me: Halloween’s done, it said, the pumpkins are sleeping now, smell the whiff of dead leaves, of bonfires coming, of loose skin over fleshless bones, of goodbyes, changes. I could smell it all. And again the sea, on the wind, as though I were a ship moving through waves.

I thought I caught a hint of the brown-suited stranger’s musky aftershave; I inhaled deeply and looked around for him. But I was alone; perhaps it was just my memory. The stranger really had reminded me of the grandfather I’d never met: Colin.

In the taxi I tried to remember more about him. I only knew flashes of drama, the medals given, the number of men dead, the bravery – sensational things fit for the blurb on a paperback. My dad used to say Colin never really recovered from his ordeal and all that kept him going afterwards were his three small children. This I now understood; this I now felt.

The taxi drove parallel to the River Humber, by the crumbling Lord Line Building, past rusted trawler boats, muddy waters, and the disused Sea Fish Industry Authority building at St Andrew’s Dock. Long grass grew up around brick, like hands from the ocean reclaiming what was once theirs. These fish docks, years ago, were the busiest in Hull. Now they were abandoned, like those further east along the river, where merchant seamen once set sail in gleaming ships, where Colin would have departed long ago.

As the taxi left the river and we passed dying orange lanterns and discarded witch hats in front gardens, I tried to remember the stories about Colin, but they had died with my childhood. I could ask my dad or uncle or aunt for his full history but I worried it might make them sad.

I closed my eyes and tried to recall seeing Grandad Colin at the end of my bed years ago. Hadn’t I smelt the sea then, too? Were those the high-temperature-fuelled hallucinations of a child who’d frequently had tonsillitis, or had I seen a ghost? Had I imagined the recurring sea breeze while worrying about Rose? Had I yesterday fantasised the somehow familiar brown-suited stranger?

Did trauma induce such imaginings?

But no, the man at the hospital had been too real. He’d been there. I could still feel his chin whiskers scraping my cheek. He’d probably reminded me of Colin because I’d craved the comfort my visions had given me when I was tiny. Now, with my own child ill, I’d needed someone bigger, someone braver than myself.

The thought of her, alone at the hospital, turned my stomach over.

‘Is this the street?’ asked the taxi driver.

‘Yes.’ I was relieved. I could do what I needed and hurry back to Rose’s bedside. ‘My house is just past the lamppost.’

I leaned forward in my seat to check it was still there. April’s overgrown hedge meant you had to be parked right in front of the door to see us. And there we were. Our home, not burned down, the house we’d bought ten years earlier because it was close enough to a main road and the local shops and schools, but safely tucked away at the end of a cul-de-sac.

I liked safe, hidden, private. Not having to make small talk with residents too often, being able to go to them if needed. Close but far. My love of privacy came from my father, a man who liked his own space; my mother’s traits were weaker in me; but my occasional need for company and converse came from her, a social butterfly who flitted happily here and there.

‘There you go.’

I gave the driver a generous tip because he’d not bothered me with unnecessary chat, and went inside.

I’d actually thought to lock the door after me earlier. Our pumpkin wasn’t lit, the face we’d carved not visible in the darkened kitchen. I switched on the light and lifted its lid. The candle inside hadn’t burned down all the way. It was hard to work out how long it must have burned after we left the house in a rush of muddy footprints and strange costumes. But this certainly didn’t look like a candle that had had been alight for hours and hours, only dying when it ran out of wick – it had been extinguished. Had someone blown it out or had it flickered and faded in some errant breeze?

There was no way of knowing.

I went into the dining room. One of Rose’s books stood on the table on its edge; triangular, like a tent. I missed our shared stories. She read privately now, to herself. I missed the perfume of her hair and the book pages, the discarded peel of her after-school orange.

Behind the table was the book nook, a place Rose had created and christened when she was five.

‘How do you know the word nook?’ I’d asked her, thinking it was an odd choice for a five-year-old.

‘Mrs Atkinson at school told me,’ she’d said. ‘It was in this story about fairies and they had one. She said it was a cosy and nice place. You can make magic and stuff there. Plus book rhymes with nook.’

So we filled our book nook with two cinnamon-coloured cushions and a bookshelf donated by Rose’s aunt Lily. Over the years our collection of books grew and grew. We picked them up in charity shops, at jumble sales, at book fairs and at Christmas. Most evenings Jake used to come home to us reclined in our squishy cushions, me reading, Rose in rapture.

‘You’re like two mice,’ he’d say. ‘Peace for me anyway.’

I sank into one of the cushions now. Though Rose rarely came here anymore, having naturally begun to enjoy TV shows more, I’d never had the heart to change it. Instead she kept books beneath her pillow, secret, selfish reads, each with a colourful marker like a flower growing from the words.

The night after Jake left I’d come here in the dark and cried a little. Now I did the same; I knew if I did I’d be able to call Jake without a fuss, be able go back to the hospital and greet Rose without burdening her, be able to do whatever diabetes dictated.

I buried my face in a cushion – even though I had no witness – and cried the way children do; greedily, loudly, unabashedly. When I was done I wiped my eyes with a corner of the artfully stained dress and realised I’d marked the cushion, as though I’d bled there. As though a pastel nurse had pricked my finger end to read its blood and spilt some.

I realised blood would soon be our life.

It was time to call Jake. I didn’t want to. During the night I’d even considered letting him escape the upset. Why not tell him when he returned on his leave in two months? What could he do anyway, out there in a warzone? Might the news detract him from his duties, put him in danger?

But I knew him – I knew he’d want to know; have to know.

Our last call had been in the middle of October, out of the blue. He couldn’t make promises about when he’d next ring – a sergeant in charge of a twenty-eight-man platoon in Kabul isn’t able to nip off to the phone whenever he fancies. I knew this and accepted it, so I never tried to anticipate our next conversation. So when he did manage to get through, it was a pleasant surprise.

I got my welfare card from the drawer in the bathroom cabinet, where it was hidden beneath old cream bottles and vitamin packets; it was the most precious thing I owned right now, so I feared carrying it around or leaving it where burglars might search for valuables. All army wives are given them when husbands tour unreachable places. On this credit-card-sized slip is necessary emergency information, most importantly a helpline number so soldiers can be contacted in extreme circumstances.

This was an extreme circumstance.

I told the operator Jake’s full name, rank and number so he could be alerted. She said it might be an hour until he called back so I asked if he’d ring my mobile and gave her the number.

Upstairs I finally changed out of my too-short nurse dress and washed my powdery face. Which clothes should I wear to learn how to inject my own child numerous times a day? What colour complemented blood? Festive green? Bleakest black? Perhaps I should pick my favourite dress with pink roses that I’d worn to a recent family christening, when Rose had said, ‘There are tiny little me’s all over it!’ Or was a dress so cheerful making light of her diagnosis?

I put on leggings and a jumper, and went to Rose’s room. Opening the door was like opening the lid on a favourite perfume bottle – its scent was familiar and uplifting and stimulated all my senses. She lived in chaos; papers and ribbons and socks and DVDs and stuffed toys and toothbrushes were scattered across the floor and surfaces. I’d long ago given up nagging and following her around with a bin bag. It seemed that, as in maths, where two negatives make a positive, two orderly parents make a messy child.

The bed was unmade; only one part was straight – its pillow, with two books beneath. Tornados have a clear, calm centre with low pressure; Rose’s books were this centre. While she might happily drop clothes in her wake, discard paper without a thought, she never went to sleep without putting her latest reads beneath her head, as though the words might somehow penetrate her dreams.

I took them out. She was reading War Horse and The Snow Goose. Animals were her favourite characters.

‘Animals are more interesting than people,’ she once said. ‘People do my head in. But animals always behave so much more better. They’re never dickheads.’

To which I’d, of course, said, ‘Language,’ and we’d argued about my swearing and how she was only copying me.

I needed to get back to the hospital. I put Rose’s books in a bag with some snacks, a toothbrush, hairbrush and some of her clothes. Then I drove through the pre-dawn streets, no radio, no distraction, but no peace.

When my phone rang I didn’t even look to see who it was. I pulled over by Rose’s school and answered, my hand shaking.

‘Are you okay?’ asked Jake, no hello or other greeting. Usually we began gently, using affectionate nicknames and slightly shy from having not spoken in weeks.

‘I’m fine,’ I lied. ‘It’s not me, it’s…’

‘Rose? God, is she okay?’

‘No. Yes. I mean – she will be.’

‘Will be? What’s happened?’

‘She collapsed,’ I said. ‘It was all so crazy, so fast. She was…’

‘What do you mean “collapsed”? Why? Where is she now?’ I understood Jake’s panic, his need to demand answers. I’d been in that place only hours ago and so now I wanted to ease his anxiety as Gill had mine.

‘She’s in the hospital,’ I said, ‘still unconscious, but they…’

‘Where are you?’ he demanded.