1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Klondike Classics

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

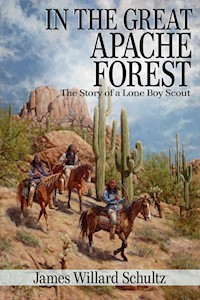

In the Great Apache Forest is the true story of 17-year-old white settler George Crosby who being too young to serve his country in France during World War I becomes a member of the forest service in Arizona, where he encounters troublesome outlaws and helps to rout them with the help of a Hopi boy and his tribal elders. The Apache National Forest covered most of Greenlee County, Arizona southern Apache County, Arizona, and part of western Catron County, New Mexico. It was a rare, untouched place, far from the nearest railroad, and boasted grizzly bears, black bears, mule deer and Mexican whitetail deer, and wild turkeys and blue grouse in great numbers.

*Newly edited text.

*Hand-curated original images.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

In the Great Apache Forest

James Willard Schultz

Published by Klondike Classics, 2018.

Copyright

––––––––

In the Great Apache Forest by James Willard Schultz. First published in 1920.

––––––––

Cover, interior design and editing © Copyright 2018 Klondike Classics. All rights reserved.

––––––––

First e-book edition 2018.

––––––––

ISBN: 978-1-387-66811-3.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Introducing the Hero

I: Alone on Mount Thomas

II: The Mountain Cave

III: The Firebugs at Work

IV: Hunting the Deserter

V: The People-of-Peace

VI: The Wrongs of the Hopis

VII: The Old Men in Rain God’s Cave

VIII: The Death of Old Double Killer

IX: The Bear Skin is Stolen

X: Catching the Firebugs

Image Gallery

Further Reading: James Willard Schultz Collection

Introducing the Hero

THIS IS TO BE GEORGE Crosby’s — the Lone Boy Scout’s — own story. But before I set it down, as he told it evening after evening before the big fireplace in my shooting lodge, some explanations are necessary.* [*I have, of course, in many instances changed the narrator’s wording, but it is his story, all the same.]

George Crosby was born and has lived all of his seventeen years, in Greer, a settlement of a half-dozen pioneer families located on the Little Colorado River, in the White Mountains, Arizona, and 108 miles south of the nearest railway, the Santa Fe, at Holbrook. Here is a high country; the altitude of Greer is 8500 feet, and south of it there is a steady rise for eleven miles to the summit of the range, Mount Thomas, 11,460 feet. And here, covering both slopes of the White Mountains, is the largest virgin forest that we have outside of Alaska, the Apache National Forest. It is about a hundred miles wide, and more than that in length, and contains millions of feet of centuries-old Douglas fir, white pine, and spruce. But it is an open forest — one can ride at will through most of it, and it is interspersed with many parks of open grassland of varying extent. On its southern slope it adjoins the reservation of the White Mountain Apaches, who are still carefully watched by several companies of United States Cavalry, stationed at Fort Apache. Because it is so remote from the railroads, the great forest still harbors an abundance of game animals and birds, and its cold, pure streams are full of trout. Here the sportsman can still find grizzly bears, some of them of great size. There are black bears, also, and mule deer and Mexican whitetail deer, and of wild turkeys and blue grouse great numbers. Cougars, wolves, coyotes, and lesser prowlers of the night are quite numerous, and in most of the streams the beavers are ever at work upon their dams and lodges.

The settlers of Greer are a hardy people. Born and reared at this great altitude, they are men and women and children of more than the average height, and of tremendous lung expansion. Theirs is one continuous struggle with Nature for the necessities of life, for here, in the heart of Arizona, they are actually in a sub-Arctic climate. Summer frosts — even in August — sometimes kill their fields of oats, and in the deep snows of the winters some of their cattle frequently perish. But they do their best, these mountain people. Though their crops fail and their livestock die, they “carry on” with hopeful hearts. And remote from civilization though they are — some of them have never seen a railroad — they are surprisingly well informed of world activities. For they have a tri-weekly mail service and subscribe for all the best magazines and several daily papers, and thoroughly read them. They are all patriotic: when the war broke out their sons did not wait to be drafted; they at once enlisted, and in due time faced the Huns in France. How the women and girls then worked for the Red Cross, and the men for Liberty Bonds! From Greer Post-Office went hundreds of sweaters and pairs of well-knit stockings, and every bond allotment of the settlement was largely oversubscribed!

It was then, at the opening of the war, that George Crosby considered what he could do for the good cause. At first he used all his spare time doing chores for those whose sons had enlisted. But that was not exactly what he wanted to do; it wasn’t big enough. If he only had some authority, there was much that he could do. He had long wanted to be a member of the Boy Scouts; nothing about them in the magazines and newspapers that came to his home ever escaped his eye. And now he read of the great work they were doing toward the winning of the war, and determined that he must join the organization. But how could he do it? There could be no company of Scouts formed in Greer; he was the only boy there save two or three little toddlers. For days he brooded over the question, and then, without a word about it to his mother and stepfather, he one evening wrote the following touching appeal to me — the one man of the great outside world whom he knew, in far-away Los Angeles:

––––––––

DEAR FRIEND:

I call you friend because I know you are my friend. Your shooting lodge looks very lonesome these days, the windows all shuttered and no smoke coming out of the big chimney. We all wish that you may soon come back to it. You should come right away, for only day before yesterday, when I was hunting for some of our horses a couple of miles up the river, I saw the fresh tracks of a big grizzly bear, and I know that you want another one. Some big gobblers are using the spring just up the slope from your place.

Uncle Cleve Wiltbank has gone to the war, and so have Mark Hawes, Henry Butler, and Forest Ranger Billingslea, and we sure miss them. I am just mad because I am not old enough to go, too. But if I can only join the Boy Scouts I may be able to help, some.

Anyhow, I could then trail about after some strange men who have lately come into these mountains, and seem not to want to meet any of us. We never get more than a glimpse of them. We don’t even know where they are camped. I wish that you would get me into the Boy Scouts. I am sure that you can do it.

Your mountain friend,

GEORGE CROSBY.

––––––––

UPON RECEIVING THIS note, I at once sent it to a Phoenix, Arizona, friend who I knew was interested in the Boy Scouts organization, and the result was that, after the exchange of several letters, George Crosby became a member of a troop of the Phoenix Boy Scouts of America.

Time passed. Came the summer of 1918, and the Supervisor of the Apache National Forest found himself woefully short of men, and the dreaded fire season coming on. The most of his rangers, fire lookouts, and patrols had gone to the war, and he could not find enough men of the right sort to take their places. When word of this shortage of men reached Greer, the settlers were seriously troubled about it. Said John Butler, George Crosby’s stepfather: “This is sure bad for us. Fires will be started by the lightning, and by careless travelers, and if there are no lookouts to report them, they will gain such headway that they will burn our whole cattle range. Then we will go broke!”

“Well, I’ll be one of the lookouts if the Supervisor will take me on,” said George.

“Sure! That is the very thing for you to do—” John began, but the good mother broke in: “No! No! George is too young — too inexperienced to undertake that dangerous, lonely work. Away up on one of those peaks by himself, right where the electric storms center — right among those terrible grizzly bears — strange men prowling about in the forest, bad men, of course, or they would make themselves known to us — no, I do not want my boy to be a fireguard.”

“But those mysterious men have gone!” George exclaimed. “Roy Hall found their deserted camp. If I let the grizzlies alone, they’ll let me alone! And as to the thunderstorms, I know the rules: when they gather, the fireguards must leave the lookout stations and go down to their cabins. Don’t you fear for me, mother. I’ll be safe enough!”

“Sure he will!” John told her. “And just think, wife, of the service he will be to the country in its time of need! And now that he has become a Boy Scout, something big is expected of him. Well, here is his chance to do the big thing!”

The mother sighed. “I take back my objections,” she said. “I should not have said one word against this. If my own young brother can face the Huns in France, then it is but fair that my young son shall face the lesser dangers in this Apache Forest.”

When Forest Supervisor Frederic Winn, in Springerville, received George’s letter of application for a position as fireguard during the season, he, too, heaved a big sigh, but it was a sigh of relief. He hurried home from the office to tell Mrs. Winn that George Crosby was to be a fireguard, and then he called for his big, black horse, and rode the eighteen miles up across the desert and into the forest to Greer, to give George his necessary instructions, and tell him that his salary would be ninety dollars per month.

But there! I have talked enough. With this introduction, I let George tell his story, a story that I found exciting enough. I find, though, that I have omitted to describe his person. He was tall and well-built for his age — seventeen years — and what a powerful chest he has. That is what one gets by being born and reared at an elevation of 8500 feet!

I: Alone on Mount Thomas

IT WAS THE 28TH OF May when Supervisor Winn rode up to our place from Springerville, and told me that I could be one of his fireguards, and that he would place me on Mount Thomas. That, the highest lookout station in all the forest, was the one I wanted, but had not dared ask for. I thought that it would likely be occupied by some experienced fireguard. Twice in my life I had been on Mount Thomas, but only for an hour or so each time, and it was such an interesting place that I had longed for a chance to spend days up there. At nine o’clock on the morning of June 1, all fireguards in the forest were required to telephone the Supervisor, at Springerville, that they were in their lookout stations, ready for duty, so I had but two days to gather an outfit for my season’s work, and another day in which to move up to the little fireguard cabin just under the summit of Mount Thomas. My mother and my sister, Hannah, packed the clothing that I would need, and the towels, dishcloths, and food, and I, myself, made a good sleeping-bag by sewing a blanket and two quilts together, and slipping them into an outer cover of heavy canvas. Up to this time my one weapon had been a little 22-caliber rifle; good enough for shooting turkeys, squirrels, and even coyotes. But now I needed a real rifle, and my mother said that I could take my Uncle Cleveland’s 30-30 Winchester. I found that it was still well oiled, and the inside of the barrel as bright as a new silver dollar. I promised that I would keep it in that condition.

On the last day of May, right after breakfast, Uncle John — as I call my stepfather — and I packed my outfit upon two stout horses, and then we mounted our saddle animals and took the trail for Mount Thomas. We climbed Amburon Point, at the head of our oatfield, and between the East and West Forks of the river, and threading the seven miles of forest and open park land, struck the East Fork, where, leaving its narrow canyon at the foot of the big mountain, it meanders for a mile or more down through a narrow valley of open meadow land. Here, on the west side of the valley, rising from a narrow, pine clad slope, are the Red Cliffs, or, as some of our mountain people call them, the Painted Cliffs: high upshoots of red lava that have many a hole in them where bears sleep in winter, and where mountain lions have their young, so some of our hunters say.

Well, as we were skirting the timber strip at the foot of these cliffs, ahead of us a couple of hundred yards three coyotes suddenly broke into the open and ran across the meadow so fast that they seemed to be just long, gray streaks in the grass; and they kept looking back as they ran, not at us, but at the timber from whence they had come.

“Something in there has given them a big scare. Let’s have a look-see,” Uncle John said to me, and I was willing enough to go in. We left the pack-horses to graze about, and had not gone more than fifty yards into the timber, taking as near as we could the back trail of the coyotes, when we came to a spring that had been freshly roiled, and along its edges, deep in the black mud, were the tracks of a big grizzly. We then discovered the partly eaten carcass of a big buck mule deer a few yards beyond the spring. But Uncle John wasn’t so much interested in that as he was in the bear tracks: “Only one bear in these mountains leaves tracks the size of those, and that is old Double Killer,” he said. And just then came a swirl of wind in our faces, strong with the rank odor of bear, and our horses got it, too, and whirled about so suddenly that we nearly lost our seats; nor could we check them as they carried us out of the timber as fast as the coyotes had left it. We finally brought them to a stand at the edge of the creek, and then forced them to return to the pack-horses, quietly feeding and apparently unaware of the proximity of the big bear.

“Now, isn’t this just my usual luck!” Uncle John grumbled, as we again took the trail. “Here is old Double Killer feasting upon a deer carcass — I sure believe he stole it from a mountain lion — and here I am with no time to stop and watch for him to come back to the carcass! Yes, and without a rifle, even if I could take the time!”

“I’ll let you have my rifle, and you can watch for him this evening,” I proposed.

“Haven’t the time for it! Now that you have left home, it is up to me to milk ten cows every morning and evening,” he answered. “But what a fine chance this would be to kill the old beefeater!”

And then, after some thought, he added: “But ten to one he will not now return to the carcass until night — dusk, anyhow, and I don’t want to tackle him all by myself when it is too dark to be sure of my aim. The man who wounds that bear is going to have a big fight on his hands! Yes, and will probably get the worst of it!”

It was now just seven years that this bear had roamed our part of the country. He had first made his appearance on Escodilla Mountain, doubtless coming there from the Mogollon Range, in New Mexico. Henry Willis, a settler at the foot of Escodilla, was the first man to see him. Out hunting cattle, one day, he discovered a small band of them resting in a meadow, and as he was riding toward them a huge bear suddenly leaped into their midst from the timber, struck a steer that was lying down just one blow on the back of its neck and killed it, and then sprang from it to a cow that was getting up, and knocked her back upon the ground, killing her, too, with one blow of his huge paw. And then the bear got wind of Willis and went back into the timber. Willis hurried home and got a couple of men to watch with him for the bear to return to his kills, but he did not come until long after dark, and then he winded them and went off loudly snorting, and never did come back to the carcasses. It was some time later that the settlers learned the peculiar habit of this bear, to kill two beef animals at a time whenever he wanted meat, and so they named him “Double Killer.” He didn’t always make his two kills; the second animal that he attacked sometimes escaping with a few deep scratches, or so badly torn that it afterward died. Those who knew best the cruel work of Double Killer estimated that he made away with at least two thousand dollars’ worth of beef a year. And so, of course, many attempts were made to end his bloody career. But he avoided traps, however skillfully they were set for him, would not touch poisoned meat, and survived the bullets of the riders who occasionally got sight of him. All who saw him said that he was of huge size, that he was a silvertip, with bald — white — head, and a large white spot on his breast. The Cattlemen’s Association of Apache County was now offering a reward of two hundred dollars for the death of the bear. I asked myself if I had the courage to attempt to earn it, provided I should see the old fellow in broad daylight?

Continuing on up the meadow, we crossed the creek at the head of it and entered the heavy spruce forest that clothes the steep slopes of Mount Thomas. Here were still patches of the winter snow, in places five or six feet deep. But the Forest Service telephone line repairers had already been to the summit with their pack-train, so the trail was well broken and we made good time. Down below, the groves of Douglas firs and white pines that we had traversed were carpeted with bright flowers and full of many kinds of singing birds. Here under the tall spruces was deep silence and deep gloom that always made me shiver. The few fallen trees lay like picked bones upon the dark, needle-strewn slope. No flowers were here except those of a few scattering blueberry bushes, and not a bird did we see other than a couple of silent-flitting, drab moose birds. I was glad when, at something like 11,000 feet, we came out on the top of the ridge and into the bright sunshine, and saw above us the bare, long summit of the mountain, its rim deep with glistening snow. And then, in a little clearing, we came to the tiny fireguard cabin. Here again were flowers, and singing birds, and scampering chipmunks and squirrels. We dismounted in front of the four by six feet porch of the cabin, unpacked the horses and piled my outfit upon it, and with my Forest Service key unlocked the padlocked door and stepped inside, and found but little more than room to turn around in. The cabin is only a ten by twelve feet room of very small logs, the only kind obtainable at that height. It has two small windows; in one corner a very small cook-stove; opposite it a narrow bunk of poles; and against the wall, and near the telephone screwed to the wall, a small table. A galvanized iron, squirrel- and rat-proof food chest occupies a good share of the floor space.

“Well, here you are, snug as a bug in a rug,” said Uncle John, after a good look around, “except that it’s sure airy: you could sling a cat out between any two of the logs. They sure need chinking!”

“They will not be chinked by me; plenty of air is what I like,” I answered, little thinking how soon I was to change my mind as to the gaping spaces. We brought my outfit inside, put the things in their proper places, and had a hurried lunch. It was about two o’clock. Uncle John said he must be going, in order to arrive home in time to do the milking. Just then the telephone bell gave two short rings. I looked at the printed card hanging beside it and saw that the call was for me, and answered.

“That you, George?” came Supervisor Winn’s voice so plainly that Uncle John could also hear what he said.

“Yes, I am here,” I answered.

“Glad that you are. Green’s Peak reports a fire somewhere on 38. Go up on top and report what you see.”

“Right away,” I answered, and hung up.

“Ha! Busy already. Well, I must be going,” said Uncle John.

I helped him get the loose horses strung out on the trail, and cheerfully enough answered his goodbye. But the moment that the dwarf spruces hid him from view, my little cabin clearing seemed not to be so sunny and pleasant. “Now, you are alone, but you are not to feel lonely!” I scolded myself, and returned to the cabin for my rifle, then took the steep trail winding up through scattering, wind-torn spruces to the summit of the mountain, passing on the way drifts of snow of great depth, some of thirty feet and more.

The rocky, bare summit of this mountain is about a quarter of a mile in length — running northwest and southeast, and in its center is a gentle depression, or saddle. At its southeast end is a round, sharp uplift of rock about fifty feet in height, upon which stands the lookout station. At the other end the mountain drops off abruptly, but at a somewhat lesser height. I went straight to the station, an eight-sided, eight-windowed, conical-roofed building just large enough to contain a central chart stand, a very small stove, and [...]