0,90 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ktoczyta.pl

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

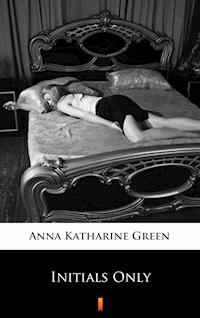

A detective story first published in 1911, it is one of the book of Ebenezer Gryce series, „Initials Only” deals with the case of beautiful young heiress Edith Challoner. She is murdered in the writing room of a luxury hotel while nobody is near her, and no shot is heard and no bullet found in the deadly wound. She is seemingly stabbed to death, yet no one was seen near her. How then was she killed? Among Miss Challoner’s personal belongings are found letters signed with initials only, O.B. Who is O.B., and what – if anything – does he have to do with her death? Sweetwater, the investigator, finds out the identity of O.B. pretty soon, but instead of answering the questions the case poses, he only brings up more mysteries.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Contents

BOOK I

AS SEEN BY TWO STRANGERS

I. POINSETTIAS

II. “I KNOW THE MAN”

III. THE MAN

IV. SWEET LITTLE MISS CLARKE

V. THE RED CLOAK

VI. INTEGRITY

VII. THE LETTERS

VIII. STRANGE DOINGS FOR GEORGE

IX. THE INCIDENT OF THE PARTLY LIFTED SHADE

BOOK II

AS SEEN BY DETECTIVE SWEETWATER

X. A DIFFERENCE OF OPINION

XI. ALIKE IN ESSENTIALS

XII. Mr. GRYCE FINDS AN ANTIDOTE FOR OLD AGE

XIII. TIME, CIRCUMSTANCE, AND A VILLAIN’S HEART

XIV. A CONCESSION

XV. THAT’S THE QUESTION

XVI. OPPOSED

XVII. IN WHICH A BOOK PLAYS A LEADING PART

XVIII. WHAT AM I TO DO NOW

XIX. THE DANGER MOMENT

XX. CONFUSION

XXI. A CHANGE

XXII. O. B. AGAIN

BOOK III

THE HEART OF MAN

XXIII. DORIS

XXIV. SUSPENSE

XXV. THE OVAL HUT

XXVI. SWEETWATER RETURNS

XXVII. THE IMAGE OF DREAD

XXVIII. I HOPE NEVER TO SEE THAT MAN

XXIX. DO YOU KNOW MY BROTHER

XXX. CHAOS

XXXI. WHAT IS HE MAKING

XXXII. TELL ME, TELL IT ALL

XXXIII. ALONE

XXXIV. THE HUT CHANGES ITS NAME

XXXV. SILENCE—AND A KNOCK

XXXVI. THE MAN WITHIN AND THE MAN WITHOUT

XXXVII. HIS GREAT HOUR

XXXVIII. NIGHT

XXXIX. THE AVENGER

XL. DESOLATE

XLI. FIVE O’CLOCK IN THE MORNING

XLII. AT SIX

BOOK I

AS SEEN BY TWO STRANGERS

I. POINSETTIAS

“A remarkable man!”

It was not my husband speaking, but some passerby. However, I looked up at George with a smile, and found him looking down at me with much the same humour. We had often spoken of the odd phrases one hears in the street, and how interesting it would be sometimes to hear a little more of the conversation.

“That’s a case in point,” he laughed, as he guided me through the crowd of theatre-goers which invariably block this part of Broadway at the hour of eight. “We shall never know whose eulogy we have just heard. ‘A remarkable man!’ There are not many of them.”

“No,” was my somewhat indifferent reply. It was a keen winter night and snow was packed upon the walks in a way to throw into sharp relief the figures of such pedestrians as happened to be walking alone. “But it seems to me that, so far as general appearance goes, the one in front answers your description most admirably.”

I pointed to a man hurrying around the corner just ahead of us.

“Yes, he’s remarkably well built. I noticed him when he came out of the Clermont.” This was a hotel we had just passed.

“But it’s not only that. It’s his height, his very striking features, his expression–” I stopped suddenly, gripping George’s arm convulsively in a surprise he appeared to share. We had turned the corner immediately behind the man of whom we were speaking and so had him still in full view.

“What’s he doing?” I asked, in a low whisper. We were only a few feet behind. “Look! look! don’t you call that curious?”

My husband stared, then uttered a low, “Rather.” The man ahead of us, presenting in every respect the appearance of a gentleman, had suddenly stooped to the kerb and was washing his hands in the snow, furtively, but with a vigour and purpose which could not fail to arouse the strangest conjectures in any chance onlooker.

“Pilate!” escaped my lips, in a sort of nervous chuckle. But George shook his head at me.

“I don’t like it,” he muttered, with unusual gravity. “Did you see his face?” Then as the man rose and hurried away from us down the street, “I should like to follow him. I do believe–”

But here we became aware of a quick rush and sudden clamour around the corner we had just left, and turning quickly, saw that something had occurred on Broadway which was fast causing a tumult.

“What’s the matter?” I cried. “What can have happened? Let’s go see, George. Perhaps it has something to do with our man.”

My husband, with a final glance down the street at the fast disappearing figure, yielded to my importunity, and possibly to some new curiosity of his own.

“I’d like to stop that man first,” said he. “But what excuse have I? He may be nothing but a crank, with some crack-brained idea in his head. We’ll soon know; for there’s certainly something wrong there on Broadway.”

“He came out of the Clermont,” I suggested.

“I know. If the excitement isn’t there, what we’ve just seen is simply a coincidence.” Then, as we retraced our steps to the corner “Whatever we hear or see, don’t say anything about this man. It’s after eight, remember, and we promised Adela that we would be at the house before nine.”

“I’ll be quiet.”

“Remember.”

It was the last word he had time to speak before we found ourselves in the midst of a crowd of men and women, jostling one another in curiosity or in the consternation following a quick alarm. All were looking one way, and, as this was towards the entrance of the Clermont, it was evident enough to us that the alarm had indeed had its origin in the very place we had anticipated. I felt my husband’s arm press me closer to his side as we worked our way towards the entrance, and presently caught a warning sound from his lips as the oaths and confused cries everywhere surrounding us were broken here and there by articulate words and we heard:

“Is it murder?”

“The beautiful Miss Challoner!”

“A millionairess in her own right!”

“Killed, they say.”

“No, no! suddenly dead; that’s all.”

“George, what shall we do?” I managed to cry into my husband’s ear.

“Get out of this. There is no chance of our reaching that door, and I can’t have you standing round any longer in this icy slush.”

“But–but is it right?” I urged, in an importunate whisper. “Should we go home while he–”

“Hush! My first duty is to you. We will go make our visit; but to-morrow–”

“I can’t wait till to-morrow,” I pleaded, wild to satisfy my curiosity in regard to an event in which I naturally felt a keen personal interest.

He drew me as near to the edge of the crowd as he could. There were new murmurs all about us.

“If it’s a case of heart-failure, why send for the police?” asked one.

“It is better to have an officer or two here,” grumbled another.

“Here comes a cop.”

“Well, I’m going to vamoose.”

“I’ll tell you what I’ll do,” whispered George, who, for all his bluster was as curious as myself. “We will try the rear door where there are fewer persons. Possibly we can make our way in there, and if we can, Slater will tell us all we want to know.”

Slater was the assistant manager of the Clermont, and one of George’s oldest friends.

“Then hurry,” said I. “I am being crushed here.”

George did hurry, and in a few minutes we were before the rear entrance of the great hotel. There was a mob gathered here also, but it was neither so large nor so rough as the one on Broadway. Yet I doubt if we should have been able to work our way through it if Slater had not, at that very instant, shown himself in the doorway, in company with an officer to whom he was giving some final instructions. George caught his eye as soon as he was through with the man, and ventured on what I thought a rather uncalled for plea.

“Let us in, Slater,” he begged. “My wife feels a little faint; she has been knocked about so by the crowd.”

The manager glanced at my face, and shouted to the people around us to make room. I felt myself lifted up, and that is all I remember of this part of our adventure. For, affected more than I realised by the excitement of the event, I no sooner saw the way cleared for our entrance than I made good my husband’s words by fainting away in earnest.

When I came to, it was suddenly and with perfect recognition of my surroundings. The small reception room to which I had been taken was one I had often visited, and its familiar features did not hold my attention for a moment. What I did see and welcome was my husband’s face bending close over me, and to him I spoke first. My words must have sounded oddly to those about. “Have they told you anything about it?” I asked. “Did he–”

A quick pressure on my arm silenced me, and then I noticed that we were not alone. Two or three ladies stood near, watching me, and one had evidently been using some restorative, for she held a small vinaigrette in her hand. To this lady, George made haste to introduce me, and from her I presently learned the cause of the disturbance in the hotel.

It was of a somewhat different nature from what I expected, and during the recital, I could not prevent myself from casting furtive and inquiring glances at George.

Edith, the well-known daughter of Moses Challoner, had fallen suddenly dead on the floor of the mezzanine. She was not known to have been in poor health, still less in danger of a fatal attack, and the shock was consequently great to her friends, several of whom were in the building. Indeed, it was likely to prove a shock to the whole community, for she had great claims to general admiration, and her death must be regarded as a calamity to persons in all stations of life.

I realised this myself, for I had heard much of the young lady’s private virtues, as well as of her great beauty and distinguished manner. A heavy loss, indeed, but–

“Was she alone when she fell?” I asked.

“Virtually alone. Some persons sat on the other side of the room, reading at the big round table. They did not even hear her fall. They say that the band was playing unusually loud in the musicians’ gallery.”

“Are you feeling quite well, now?”

“Quite myself,” I gratefully replied as I rose slowly from the sofa. Then, as my kind informer stepped aside, I turned to George with the proposal we should go now.

He seemed as anxious as myself to leave and together we moved towards the door, while the hum of excited comment which the intrusion of a fainting woman had undoubtedly interrupted, recommenced behind us till the whole room buzzed.

In the hall we encountered Mr. Slater, whom I have before mentioned. He was trying to maintain order while himself in a state of great agitation. Seeing us, he could not refrain from whispering a few words into my husband’s ear.

“The doctor has just gone up–her doctor, I mean. He’s simply dumbfounded. Says that she was the healthiest woman in New York yesterday–I think–don’t mention it, that he suspects something quite different from heart failure.”

“What do you mean?” asked George, following the assistant manager down the broad flight of steps leading to the office. Then, as I pressed up close to Mr. Slater’s other side, “She was by herself, wasn’t she, in the half floor above?”

“Yes, and had been writing a letter. She fell with it still in her hand.”

“Have they carried her to her room?” I eagerly inquired, glancing fearfully up at the large semi-circular openings overlooking us from the place where she had fallen.

“Not yet. Mr. Hammond insists upon waiting for the coroner.” (Mr. Hammond was the proprietor of the hotel.) “She is lying on one of the big couches near which she fell. If you like, I can give you a glimpse of her. She looks beautiful. It’s terrible to think that she is dead.”

I don’t know why we consented. We were under a spell, I think. At all events, we accepted his offer and followed him up a narrow staircase open to very few that night. At the top, he turned upon us with a warning gesture which I hardly think we needed, and led us down a narrow hall flanked by openings corresponding to those we had noted from below. At the furthest one he paused and, beckoning us to his side, pointed across the lobby into the large writing-room which occupied the better part of the mezzanine floor.

We saw people standing in various attitudes of grief and dismay about a couch, one end of which only was visible to us at the moment. The doctor had just joined them, and every head was turned towards him and every body bent forward in anxious expectation. I remember the face of one grey haired old man. I shall never forget it. He was probably her father. Later, I knew him to be so. Her face, even her form, was entirely hidden from us, but as we watched (I have often thought with what heartless curiosity) a sudden movement took place in the whole group–and for one instant a startling picture presented itself to our gaze. Miss Challoner was stretched out upon the couch. She was dressed as she came from dinner, in a gown of ivory-tinted satin, relieved at the breast by a large bouquet of scarlet poinsettias. I mention this adornment, because it was what first met and drew our eyes and the eyes of every one about her, though the face, now quite revealed, would seem to have the greater attraction. But the cause was evident and one not to be resisted. The doctor was pointing at these poinsettias in horror and with awful meaning, and though we could not hear his words, we knew almost instinctively, both from his attitude and the cries which burst from the lips of those about him, that something more than broken petals and disordered laces had met his eyes; that blood was there–slowly oozing drops from the heart–which for some reason had escaped all eyes till now.

Miss Challoner was dead, not from unsuspected disease, but from the violent attack of some murderous weapon; As the realisation of this brought fresh panic and bowed the old father’s head with emotions even more bitter than those of grief, I turned a questioning look up at George’s face.

It was fixed with a purpose I had no trouble in understanding.

II. “I KNOW THE MAN”

Yet he made no effort to detain Mr. Slater, when that gentleman, under this renewed excitement, hastily left us. He was not the man to rush into anything impulsively, and not even the presence of murder could change his ways.

“I want to feel sure of myself,” he explained. “Can you bear the strain of waiting around a little longer, Laura? I mustn’t forget that you fainted just now.”

“Yes, I can bear it; much better than I could bear going to Adela’s in my present state of mind. Don’t you think the man we saw had something to do with this? Don’t you believe–”

“Hush! Let us listen rather than talk. What are they saying over there? Can you hear?”

“No. And I cannot bear to look. Yet I don’t want to go away. It’s all so dreadful.”

“It’s devilish. Such a beautiful girl! Laura, I must leave you for a moment. Do you mind?”

“No, no; yet–”

I did mind; but he was gone before I could take back my word. Alone, I felt the tragedy much more than when he was with me. Instead of watching, as I had hitherto done, every movement in the room opposite, I drew back against the wall and hid my eyes, waiting feverishly for George’s return.

He came, when he did come, in some haste and with certain marks of increased agitation.

“Laura,” said he, “Slater says that we may possibly be wanted and proposes that we stay here all night. I have telephoned Adela and have made it all right at home. Will you come to your room? This is no place for you.”

Nothing could have pleased me better; to be near and yet not the direct observer of proceedings in which we took so secret an interest! I showed my gratitude by following George immediately. But I could not go without casting another glance at the tragic scene I was leaving. A stir was perceptible there, and I was just in time to see its cause. A tall, angular gentleman was approaching from the direction of the musicians’ gallery, and from the manner of all present, as well as from the whispered comment of my husband, I recognised in him the special official for whom all had been waiting.

“Are you going to tell him?” was my question to George as we made our way down to the lobby.

“That depends. First, I am going to see you settled in a room quite remote from this business.”

“I shall not like that.”

“I know, my dear, but it is best.”

I could not gainsay this.

Nevertheless, after the first few minutes of relief, I found it very lonesome upstairs. The pictures which crowded upon me of the various groups of excited and wildly gesticulating men and women through which we had passed on our way up, mingled themselves with the solemn horror of the scene in the writing-room, with its fleeting vision of youth and beauty lying pulseless in sudden death. I could not escape the one without feeling the immediate impress of the other, and if by chance they both yielded for an instant to that earlier scene of a desolate street, with its solitary lamp shining down on the crouched figure of a man washing his shaking hands in a drift of freshly fallen snow, they immediately rushed back with a force and clearness all the greater for the momentary lapse.

I was still struggling with these fancies when the door opened, and George came in. There was news in his face as I rushed to meet him.

“Tell me–tell,” I begged.

He tried to smile at my eagerness, but the attempt was ghastly.

“I’ve been listening and looking,” said he, “and this is all I have learned. Miss Challoner died, not from a stroke or from disease of any kind, but from a wound reaching the heart. No one saw the attack, or even the approach or departure of the person inflicting this wound. If she was killed by a pistol-shot, it was at a distance, and almost over the heads of the persons sitting at the table we saw there. But the doctors shake their heads at the word pistol-shot, though they refuse to explain themselves or to express any opinion till the wound has been probed. This they are going to do at once, and when that question is decided, I may feel it my duty to speak and may ask you to support my story.”

“I will tell what I saw,” said I.

“Very good. That is all that will be required. We are strangers to the parties concerned, and only speak from a sense of justice. It may be that our story will make no impression, and that we shall be dismissed with but few thanks. But that is nothing to us. If the woman has been murdered, he is the murderer. With such a conviction in my mind, there can be no doubt as to my duty.”

“We can never make them understand how he looked.”

“No. I don’t expect to.”

“Or his manner as he fled.”

“Nor that either.”

“We can only describe what we saw him do.”

“That’s all.”

“Oh, what an adventure for quiet people like us! George, I don’t believe he shot her.”

“He must have.”

“But they would have seen–have heard–the people around, I mean.”

“So they say; but I have a theory–but no matter about that now. I’m going down again to see how things have progressed. I’ll be back for you later. Only be ready.”

Be ready! I almost laughed,–a hysterical laugh, of course, when I recalled the injunction. Be ready! This lonely sitting by myself, with nothing to do but think was a fine preparation for a sudden appearance before those men–some of them police-officers, no doubt.

But that’s enough about myself; I’m not the heroine of this story. In a half hour or an hour–I never knew which–George reappeared only to tell me that no conclusions had as yet been reached; an element of great mystery involved the whole affair, and the most astute detectives on the force had been sent for. Her father, who had been her constant companion all winter, had not the least suggestion to offer in way of its solution. So far as he knew–and he believed himself to have been in perfect accord with his daughter–she had injured no one. She had just lived the even, happy and useful life of a young woman of means, who sees duties beyond those of her own household and immediate surroundings. If, in the fulfillment of those duties, she had encountered any obstacle to content, he did not know it; nor could he mention a friend of hers–he would even say lovers, since that was what he meant–who to his knowledge could be accused of harbouring any such passion of revenge as was manifested in this secret and diabolical attack. They were all gentlemen and respected her as heartily as they appeared to admire her. To no living being, man or woman, could he point as possessing any motive for such a deed. She had been the victim of some mistake, his lovely and ever kindly disposed daughter, and while the loss was irreparable he would never make it unendurable by thinking otherwise.

Such was the father’s way of looking at the matter, and I own that it made our duty a trifle hard. But George’s mind, when once made up, was persistent to the point of obstinacy, and while he was yet talking he led me out of the room and down the hall to the elevator.

“Mr. Slater knows we have something to say, and will manage the interview before us in the very best manner,” he confided to me now with an encouraging air. “We are to go to the blue reception room on the parlour floor.”

I nodded, and nothing more was said till we entered the place mentioned. Here we came upon several gentlemen, standing about, of a more or less professional appearance. This was not very agreeable to one of my retiring disposition, but a look from George brought back my courage, and I found myself waiting rather anxiously for the questions I expected to hear put.

Mr. Slater was there according to his promise, and after introducing us, briefly stated that we had some evidence to give regarding the terrible occurrence which had just taken place in the house.

George bowed, and the chief spokesman–I am sure he was a police-officer of some kind–asked him to tell what it was.

George drew himself up–George is not one of your tall men, but he makes a very good appearance at times. Then he seemed suddenly to collapse. The sight of their expectation made him feel how flat and childish his story would sound. I, who had shared his adventure, understood his embarrassment, but the others were evidently at a loss to do so, for they glanced askance at each other as he hesitated, and only looked back when I ventured to say:

“It’s the peculiarity of the occurrence which affects my husband. The thing we saw may mean nothing.”

“Let us hear what it was and we will judge.”

Then my husband spoke up, and related our little experience. If it did not create a sensation, it was because these men were well accustomed to surprises of all kinds.

“Washed his hands–a gentleman–out there in the snow–just after the alarm was raised here?” repeated one.

“And you saw him come out of this house?” another put in.

“Yes, sir; we noticed him particularly.”

“Can you describe him?”

It was Mr. Slater who put this question; he had less control over himself, and considerable eagerness could be heard in his voice.

“He was a very fine-looking man; unusually tall and unusually striking both in his dress and appearance. What I could see of his face was bare of beard, and very expressive. He walked with the swing of an athlete, and only looked mean and small when he was stooping and dabbling in the snow.”

“His clothes. Describe his clothes.” There was an odd sound in Mr. Slater’s voice.

“He wore a silk hat and there was fur on his overcoat. I think the fur was black.”

Mr. Slater stepped back, then moved forward again with a determined air.

“I know the man,” said he.

III. THE MAN

“You know the man?”

“I do; or rather, I know a man who answers to this description. He comes here once in a while. I do not know whether or not he was in the building to-night, but Clausen can tell you; no one escapes Clausen’s eye.”

“His name.”

“Brotherson. A very uncommon person in many respects; quite capable of such an eccentricity, but incapable, I should say, of crime. He’s a gifted talker and so well read that he can hold one’s attention for hours. Of his tastes, I can only say that they appear to be mainly scientific. But he is not averse to society, and is always very well dressed.”

“A taste for science and for fine clothing do not often go together.”

“This man is an exception to all rules. The one I’m speaking of, I mean. I don’t say that he’s the fellow seen pottering in the snow.”

“Call up Clausen.”

The manager stepped to the telephone.

Meanwhile, George had advanced to speak to a man who had beckoned to him from the other side of the room, and with whom in another moment I saw him step out. Thus deserted, I sank into a chair near one of the windows. Never had I felt more uncomfortable. To attribute guilt to a totally unknown person–a person who is little more to you than a shadowy silhouette against a background of snow–is easy enough and not very disturbing to the conscience. But to hear that person named; given positive attributes; lifted from the indefinite into a living, breathing actuality, with a man’s hopes, purposes and responsibilities, is an entirely different proposition. This Brotherson might be the most innocent person alive; and, if so, what had we done? Nothing to congratulate ourselves upon, certainly. And George was not present to comfort and encourage me. He was–

Where was he? The man who had carried him off was the youngest in the group. What had he wanted of George? Those who remained showed no interest in the matter. They had enough to say among themselves. But I was interested–naturally so, and, in my uneasiness, glanced restlessly from the window, the shade of which was up. The outlook was a very peaceful one. This room faced a side street, and, as my eyes fell upon the whitened pavements, I received an answer to one, and that the most anxious, of my queries. This was the street into which we had turned, in the wake of the handsome stranger they were trying at this very moment to identify with Brotherson. George had evidently been asked to point out the exact spot where the man had stopped, for I could see from my vantage point two figures bending near the kerb, and even pawing at the snow which lay there. It gave me a slight turn when one of them–I do not think it was George–began to rub his hands together in much the way the unknown gentleman had done, and, in my excitement, I probably uttered some sort of an ejaculation, for I was suddenly conscious of a silence in the room, and when I turned saw all the men about me looking my way.

I attempted to smile, but instead, shuddered painfully, as I raised my hand and pointed down at the street.

“They are imitating the man,” I cried; “my husband and–and the person he went out with. It looked dreadful to me; that is all.”

One of the gentlemen immediately said some kind words to me, and another smiled in a very encouraging way. But their attention was soon diverted, and so was mine by the entrance of a man in semi-uniform, who was immediately addressed as Clausen.

I knew his face. He was one of the doorkeepers; the oldest employee about the hotel, and the one best liked. I had often exchanged words with him myself.

Mr. Slater at once put his question:

“Has Mr. Brotherson passed your door at any time to-night?”

“Mr. Brotherson! I don’t remember, really I don’t,” was the unexpected reply. “It’s not often I forget. But so many people came rushing in during those few minutes, and all so excited–”

“Before the excitement, Clausen. A little while before, possibly just before.”

“Oh, now I recall him! Yes, Mr. Brotherson went out of my door not many minutes before the cry upstairs. I forgot because I had stepped back from the door to hand a lady the muff she had dropped, and it was at that minute he went out. I just got a glimpse of his back as he passed into the street.”

“But you are sure of that back?”

“I don’t know another like it, when he wears that big coat of his. But Jim can tell you, sir. He was in the cafe up to that minute, and that’s where Mr. Brotherson usually goes first.”

“Very well; send up Jim. Tell him I have some orders to give him.”

The old man bowed and went out.

Meanwhile, Mr. Slater had exchanged some words with the two officials, and now approached me with an expression of extreme consideration. They were about to excuse me from further participation in this informal inquiry. This I saw before he spoke. Of course they were right. But I should greatly have preferred to stay where I was till George came back.

However, I met him for an instant in the hall before I took the elevator, and later I heard in a round-about way what Jim and some others about the house had to say of Mr. Brotherson.

He was an habitue of the hotel, to the extent of dining once or twice a week in the cafe, and smoking, afterwards, in the public lobby. When he was in the mood for talk, he would draw an ever-enlarging group about him, but at other times he would be seen sitting quite alone and morosely indifferent to all who approached him. There was no mystery about his business. He was an inventor, with one or two valuable patents already on the market. But this was not his only interest. He was an all round sort of man, moody but brilliant in many ways–a character which at once attracted and repelled, odd in that he seemed to set little store by his good looks, yet was most careful to dress himself in a way to show them off to advantage. If he had means beyond the ordinary no one knew it, nor could any man say that he had not. On all personal matters he was very close-mouthed, though he would talk about other men’s riches in a way to show that he cherished some very extreme views.

This was all which could be learned about him off-hand, and at so late an hour. I was greatly interested, of course, and had plenty to think of till I saw George again and learned the result of the latest investigations.

Miss Challoner had been shot, not stabbed. No other deduction was possible from such facts as were now known, though the physicians had not yet handed in their report, or even intimated what that report would be. No assailant could have approached or left her, without attracting the notice of some one, if not all of the persons seated at a table in the same room. She could only have been reached by a bullet sent from a point near the head of a small winding staircase connecting the mezzanine floor with a coat-room adjacent to the front door. This has already been insisted on, as you will remember, and if you will glance at the diagram which George hastily scrawled for me, you will see why.

A. B., as well as C. D., are half circular openings into the office lobby. E. F. are windows giving upon Broadway, and G. the party wall, necessarily unbroken by window, door or any other opening.

It follows then that the only possible means of approach to this room lies through the archway H., or from the elevator door. But the elevator made no stop at the mezzanine on or near the time of the attack upon Miss Challoner; nor did any one leave the table or pass by it in either direction till after the alarm given by her fall.

But a bullet calls for no approach. A man at X. might raise and fire his pistol without attracting any attention to himself. The music, which all acknowledge was at its full climax at this moment, would drown the noise of the explosion, and the staircase, out of view of all but the victim, afford the same means of immediate escape, which it must have given of secret and unseen approach. The coat-room into which it descended communicated with the lobby very near the main entrance, and if Mr. Brotherson were the man, his sudden appearance there would thus be accounted for.

To be sure, this gentleman had not been noticed in the coatroom by the man then in charge, but if the latter had been engaged at that instant, as he often was, in hanging up or taking down a coat from the rack, a person might easily pass by him and disappear into the lobby without attracting his attention. So many people passed that way from the dining-room beyond, and so many of these were tall, fine-looking and well-dressed.

It began to look bad for this man, if indeed he were the one we had seen under the street-lamp; and, as George and I reviewed the situation, we felt our position to be serious enough for us severally to set down our impressions of this man before we lost our first vivid idea. I do not know what George wrote, for he sealed his words up as soon as he had finished writing, but this is what I put on paper while my memory was still fresh and my excitement unabated:

He had the look of a man of powerful intellect and determined will, who shudders while he triumphs; who outwardly washes his hands of a deed over which he inwardly gloats. This was when he first rose from the snow. Afterwards he had a moment of fear; plain, human, everyday fear. But this was evanescent. Before he had turned to go, he showed the self-possession of one who feels himself so secure, or is so well-satisfied with himself, that he is no longer conscious of other emotions.

“Poor fellow,” I commented aloud, as I folded up these words; “he reckoned without you, George. By to-morrow he will be in the hands of the police.”

“Poor fellow?” he repeated. “Better say ‘Poor Miss Challoner!’ They tell me she was one of those perfect women who reconcile even the pessimist to humanity and the age we live in. Why any one should want to kill her is a mystery; but why this man should–There! no one professes to explain it. They simply go by the facts. To-morrow surely must bring strange revelations.”

And with this sentence ringing in my mind, I lay down and endeavoured to sleep. But it was not till very late that rest came. The noise of passing feet, though muffled beyond their wont, roused me in spite of myself. These footsteps might be those of some late arrival, or they might be those of some wary detective intent on business far removed from the usual routine of life in this great hotel.

I recalled the glimpse I had had of the writing-room in the early evening, and imagined it as it was with Miss Challoner’s body removed and the incongruous flitting of strange and busy figures across its fatal floors, measuring distances and peering into corners, while hundreds slept above and about them in undisturbed repose.

Then I thought of him, the suspected and possibly guilty one. In visions over which I had little if any control, I saw him in all the restlessness of a slowly dying down excitement–the surroundings strange and unknown to me, the figure not–seeking for quiet; facing the past; facing the future; knowing, perhaps, for the first time in his life what it was for crime and remorse to murder sleep. I could not think of him as lying still–slumbering like the rest of mankind, in the hope and expectation of a busy morrow. Crime perpetrated looms so large in the soul, and this man had a soul as big as his body; of that I was assured. That its instincts were cruel and inherently evil, did not lessen its capacity for suffering. And he was suffering now; I could not doubt it, remembering the lovely face and fragrant memory of the noble woman he had, under some unknown impulse, sent to an unmerited doom.

At last I slept, but it was only to rouse again with the same quick realisation of my surroundings, which I had experienced on my recovery from my fainting fit of hours before. Someone had stopped at our door before hurrying by down the hall. Who was that someone? I rose on my elbow, and endeavoured to peer through the dark. Of course, I could see nothing. But when I woke a second time, there was enough light in the room, early as it undoubtedly was, for me to detect a letter lying on the carpet just inside the door.

Instantly I was on my feet. Catching the letter up, I carried it to the window. Our two names were on it–Mr. and Mrs. George Anderson: the writing, Mr. Slater’s.

I glanced over at George. He was sleeping peacefully. It was too early to wake him, but I could not lay that letter down unread; was not my name on it? Tearing it open, I devoured its contents,–the exclamation I made on reading it, waking George.

The writing was in Mr. Slater’s hand, and the words were:

“I must request, at the instance of Coroner Heath and such of the police as listened to your adventure, that you make no further mention of what you saw in the street under our windows last night. The doctors find no bullet in the wound. This clears Mr. Brotherson.”

IV. SWEET LITTLE MISS CLARKE

When we took our seats at the breakfast-table, it was with the feeling of being no longer looked upon as connected in any way with this case. Yet our interest in it was, if anything, increased, and when I saw George casting furtive glances at a certain table behind me, I leaned over and asked him the reason, being sure that the people whose faces I saw reflected in the mirror directly before us had something to do with the great matter then engrossing us. His answer conveyed the somewhat exciting information that the four persons seated in my rear were the same four who had been reading at the round table in the mezzanine at the time of Miss Challoner’s death.

Instantly they absorbed all my attention, though I dared not give them a direct look, and continued to observe them only in the glass.

“Is it one family?” I asked.

“Yes, and a very respectable one. Transients, of course, but very well known in Denver. The lady is not the mother of the boys, but their aunt. The boys belong to the gentleman, who is a widower.”

“Their word ought to be good.”

George nodded.

“The boys look wide-awake enough if the father does not. As for the aunt, she is sweetness itself. Do they still insist that Miss Challoner was the only person in the room with them at this time?”

“They did last night. I don’t know how they will meet this statement of the doctor’s.”

“George?”

He leaned nearer.

“Have you ever thought that she might have been a suicide? That she stabbed herself?”

“No, for in that case a weapon would have been found.”

“And are you sure that none was?”

“Positive. Such a fact could not have been kept quiet. If a weapon had been picked up there would be no mystery, and no necessity for further police investigation.”

“And the detectives are still here?”

“I just saw one.”

“George?”

Again his head came nearer.

“Have they searched the lobby? I believe she had a weapon.”

“Laura!”