Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press Classics

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

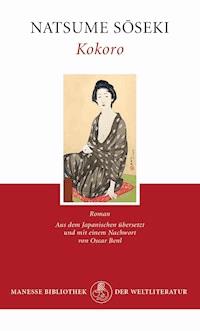

A hauntingly beautiful melodrama exploring the friendship between a young man and his mentor __________ 'Soseki is the representative modern Japanese novelist, a figure of truly national stature' Haruki Murukami 'Kokoro is exactly what you would ask a novel to be... Sōseki manipulates every detail with the same thrilling mastery' Spectator 'Sparsely populated, simple but perfect... it is a melancholy but stoical study in loneliness' Sunday Telegraph __________ In this melancholy and delicately written Japanese classic, a student befriends a reclusive elder at a beach resort, who he calls Sensei. As the two grow closer, Sensei remains unwilling to share the inner pain that has consumed his life and the shameful secret behind his monthly pilgrimages to a Tokyo cemetery. But when the student writes to Sensei after his graduation to seek out advice, the past rushes unbidden to the surface, and Sensei at last reveals the tale of romantic betrayal and unresolved guilt that led to his withdrawal from the world. Set at the end of the Meiji era and rife with subtle, psychological insight, Kokoro is one of Japan's bestselling novels of all time and a stunning meditation on the essence of loneliness.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 414

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

i

‘Kokoro is exactly what you would ask a novel to be… Sōseki manipulates every detail with the same thrilling mastery’

SPECTATOR

‘Sparsely populated, simple but perfect… it is a melancholy but stoical study in loneliness’

SUNDAY TELEGRAPH

‘Rich in understanding and insight’

THE NEW YORKER

‘Sōseki is the representative modern Japanese novelist, a figure of truly national stature’

HARUKI MURAKAMI

‘A master of in-depth characterisation and psychological realism’

FINANCIAL TIMESii

iii

KOKORO

NATSUME SŌSEKI

TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE BY EDWIN MCCLELLAN

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY DAMIAN FLANAGAN

PUSHKIN PRESS CLASSICSiv

Contents

Introduction

Readers are advised that this introduction reveals the plot of Kokoro.

Congratulations to you, dear reader, on purchasing one of the great masterpieces of world literature—but brace yourself, because you are in for a roller-coaster ride. Kokoro is simply fantastic—a Great Gatsby with extra soul—and, for some, reading it will be a life-changing experience. But the novel is also a slippery eel, as difficult to pin down as it is to put down, and exploring it can seem like wandering around a psychological labyrinth full of trap-doors. It appears at times that just about everything about it is Janus-faced.

Kokoro is a novel that is still virtually unknown in the West, and yet in Japan, and increasingly throughout East Asia, the novel has been celebrated and analysed beyond imagining. Back in 1996, for example, it was calculated that at least 450 academic papers had already been published about it, with new ones appearing at a rate of about twenty a year. Indeed so much has been written about Kokoro that a Japanese writer wishing to present something new on the text will usually preface his or her claim with a cagey line along the lines of “As far as I am aware, in what has been written so far…” Kokoro thus manages to be both one of the most celebrated novels in the world and one of the least known—draw what conclusions you will about the gulf between East and West.

The word kokoro means “heart”, although in the emotional and spiritual rather than the physical sense of the word. And, viiifor generations, Japanese readers have come to regard this novel as capturing something quintessential about their culture, as a work that gets to the heart of things. Western critics of Japanese literature have concurred and found it to be the Sōseki novel that most readily conforms to what their idea of a “Japanese novel” should be. Many of Sōseki’s other novels, influenced by his deeply idiosyncratic personality and familiarity with European literature, Chinese poetry and Western art, are works of the highest literary quality, but they do not necessarily feel particularly Japanese to Western readers. Kokoro, with its depiction of characters tormented by a sense of honour and duty, the claustrophobia of its scenes, the delicacy of sentiment, have all the elements necessary for it to seem profoundly and typically Japanese in style.

For many years Japanese schoolchildren were required to read it, or at least some of it, as a set text, as if the book had some specially edifying moral vision, but these days its content appears to be much more tricky and ambiguous than was once realized. It is the tale of an introverted man, referred to simply as Sensei—a Japanese word for a respected teacher or elder figure—who strikes up a friendship with an innocent young man. Sensei reveals to his new friend his long pent-up inner pain concerning the betrayal many years earlier of his university friend, known only as K, and which led to K committing suicide. Sensei has had to live with this terrible guilt, revealing the secret to no one, not even his wife, who as a young woman was the cause of the two friends falling out. Now, at last, he can reveal his inner suffering and finally break free from the burden that has blighted his life.

Kokoro was serialized in the Asahi (Rising Sun) newspaper between 20 April and 11 August 1914, and when the advertisement for the novel appeared in the newspaper in March it seems that Sōseki had intended that it would consist of a series of interlinked ixshort stories. Sōseki planned to call the first story in the collection “Sensei’s Testament”, but this grew and grew, until finally it became a novel in its own right. When the newspaper serialization was completed, the instalments were collected into a book. This was divided into three parts: the first part, entitled “Sensei and I”, was comprised of the first thirty-six instalments; the next eighteen instalments became the second part, “My Parents and I”; and the third part, “Sensei and His Testament”, was made up of the remaining fifty-six instalments. The overall title was Kokoro, and when the book was released as the inaugural publication of Iwanami Shoten—the publishing house founded by Sōseki’s friend Iwanami Shigeo—Sōseki took the unusual step of designing the box, the cover, the frontispiece and the title characters himself.

Kokoro immediately struck a chord with its audience. A key element of the plot towards the end of the book describes how, when the Emperor Meiji died on 30 July 1912 after a reign of forty-four years, a veteran member of Japan’s military élite, General Nogi, shocked Japan by deciding to take his life in a feudal act known as junshi—meaning “following one’s lord in death”—as atonement for losing the emperor’s flag in battle some thirty-five years earlier. In his final “testament”, the character Sensei writes that on hearing this long-forgotten word junshi, he, too, sees that the time has come for him to atone for his friend K’s death, resolving to commit suicide. For generations of readers, therefore, Kokoro was seen as a profoundly sad and deeply moving work, the last hurrah of a nobility more in tune with the feudal Edo period (1603–1867) than the ravenously capitalist, imperialist and Westernized nation born out of the waves of reform of the Meiji era (1868–1912).

But if there are those readers who find tears rolling down their cheeks every time they caress the pages of Kokoro then there are others for whom mention of the book is more likely to elicit a very xdifferent response. What? Committing suicide out of a sense of long-held guilt and reverence for “the spirit of Meiji”? If Kokoro is the reason why an older generation of Japanese worshipped Sōseki then it is equally the reason why many of a younger generation feel profoundly turned off by him. Indifference, indeed, has turned in some cases to outright mockery. “This ‘Sensei’ is, after all, a bit suspect, isn’t he?” they might say. “An older man getting very close to a young man and killing himself over the loss of a close male friend? We have a different word for that type of thing now…”

There is good reason to believe, however, that both the traditional view of it as a sincere and serious book somehow embodying the Japanese spirit and the radical counterview that all its values are suspicious are equally misplaced. Sōseki was, after all, a writer of great subtlety and a master of irony who, in early works such as I Am a Cat, showed himself to be a superb satirist. According to the traditional view of his writing career the novels become progressively more serious until somewhere around Sanshiro (1908) the humour subsides and gives way to the darkness of the later novels. Yet black humour and irony did not really disappear from Sōseki’s writings; they just began to appear in increasingly subtle ways. As we shall see, Sōseki’s aim in all his later novels was to breathe life into his characters through an intensely realistic writing style—but that doesn’t mean that he wasn’t also portraying them with devastating irony.

The Mysteries of Kokoro

If readers have found their responses to Kokoro deeply polarized, then the novel has done an even better job of confounding the legions of Japanese critics who have pored over its every sentence.

xiTraditional criticism focused on the problem of “egotism” and character motivation and viewed Kokoro as the final part of Sōseki’s second “trilogy”, sharing themes with the two novels—To the Spring Equinox and Beyond and The Wayfarer—that immediately preceded it. However, new waves of critical scrutiny began to overturn these traditional interpretations. Apart from the popularity of the novel with the general public and its use in the latter half of the twentieth century as a set text in Japanese high schools, one major reason for the intense critical scrutiny brought to bear on it was a ferocious literary debate unleashed by two Japanese critics in the mid 1980s.

Amazingly, this debate—surely one of the most intense in Japanese literary history—was triggered by an interpretation of just two small phrases in the novel. One occurs in the very first paragraph, when the narrator declares that he will call his older friend Sensei because he cannot bear to use a cold letter of the alphabet to represent his name. The significance of this tiny detail is not revealed until the final third of the novel, when we discover Sensei refers to his own friend by the letter “K”. It was, therefore, suggested by the critic Ishihara Chiaki that the narrator of the first two parts is, from the outset, adopting an implicitly critical stance of Sensei and that the nature of his relationship with the father figure is somehow Oedipal. According to Ishihara, Sensei is at once someone with whom the narrator feels a strong bond and yet against whom he also nurtures simmering resentment.

At the same time as the “Oedipus” debate was going on, an even more innocuous-seeming phrase let loose another tumultuous debate. When the narrator of the first two parts is recalling an evening spent with Sensei and his wife he uses the phrase “at the time I did not feel inclined to look at his wife so critically”. The young critic Komori Yoichi interpreted the words “at the time” xiias meaning that the narrator must now look at Sensei’s wife with more critical eyes, and, in order for him to do so, their relationship must have somehow developed after the novel ends with Sensei’s death. Sensationally, he implied that the narrator must have ended up living with Sensei’s wife. Furthermore, the narrator writes that he “did not have children at the time”, implying that he now has children, so it was suggested by some critics that the narrator may even have had children with her. This interpretation led to seemingly endless rounds of argument and counter-argument—a play was even written along the lines of this interpretation—although some critics pointed out that the polite form of address that the narrator uses for Sensei’s wife, Okusan, was entirely incompatible with his later having gone on to marry her.

These debates—extravagantly absurd as they often were—did, however, open up some unexpected aspects of Kokoro. In particular, given that the novel is a narrative in which three male characters—the narrator, Sensei and K—occupy centre stage, it led to a great deal of analysis being brought to bear on Sensei’s wife. She is called Shizu, which means “quiet”, and she is at best a shadowy figure who is somewhat sidelined in the story. There has, for example, been much debate about how much Shizu really knows about her husband’s torment over K’s death, with some critics highlighting the suspicion that she perhaps knows more than she is prepared to tell. Debate has polarized from presenting Shizu as a pure Madonna figure to the other extreme of seeing her as a calculating woman who knows exactly what has happened to Sensei in the past but who feigns ignorance.

Yet, even beyond the bounds of these literary debates, critics have found that there are many elements in the novel that are intriguingly ambiguous. Take, for example, the question of what exact point in time the narrator is supposed to be telling his story. xiiiAt first one might assume that since Sōseki wrote the novel in 1914 the narrative present is also supposed to be 1914. But it is also hinted that the narrator—a young man when Sensei dies in 1912—is reminiscing about something from his youth.

In the story, when the narrator first meets Sensei he appears to be a third-year student at the First Higher School, an élite institute of higher education that scholars entered when they were about eighteen and left when they were in their early twenties before proceeding to Tokyo Imperial University. By the time of Sensei’s death the narrator is a university graduate, and so at least four years have passed and he must be in his mid-twenties. Yet one senses that the narrator is no longer a man in his twenties but a middle-aged figure reminiscing at a distance.

The more times one reads Kokoro the more one begins to notice patterns of repetition. It is almost as if there are no personalities, just stages in life: the young man, the lover, the older man; the young girl, the wife, the mother. This point is emphasized by the fact that so few of the characters actually have real names but are simply referred to as “I”, “my father”, “his wife” and so on. And, if there are recurring stages in life then there are also eternally recurring themes: friendship, marriage, parents’ illnesses, death and inheritance.

To frame the themes of egotism and morality, love and friendship, trust and betrayal, Kokoro unfolds like a detective story. We find ourselves asking, “Who is this mysterious person Sensei? What is his secret and why has he died? Who is the person buried in Zoshigaya Cemetery and how is he connected to the story?” At the beginning Sensei reels in the younger man by hinting at an intriguing past and making sudden cryptic statements such as “I don’t trust anyone” and “all love is a sin”, yet every time Sensei seems about to elaborate on his past there is an awkward interruption, xivso that he manages to keep his secrets while promising to reveal them another day. This is what keeps both the reader and the narrator hooked. Sensei, it seems, is looking for someone to trust and to whom he can impart his knowledge, while the narrator is looking for instruction on life.

Yet even when the secrets are supposed to be revealed in “Sensei and His Testament” the mysteries merely multiply. Sensei reveals from the outset how many things have been unclear and out of control his life is. He admits how he did not even know how much his own mother knew about her own impending death and how as a young man he was swindled by his uncle. Then, paranoid and untrusting, he moves as a lodger into a family house and falls for his landlady’s daughter, but he cannot tell whether his landlady is plotting to bring him and the daughter—called Ojosan, meaning “young lady”—together in order to get her hands on his money. While he dithers, he becomes involved with his friend K, an intensely serious young man with religious aspirations who has been disowned by his own family. The young Sensei insists on moving K into his lodgings, even though his landlady advises him against it. He implores his landlady and her daughter to treat K kindly, but when they finally do so he cannot tell whether their kindness towards his friend is real or part of this plot to trick him.

And then, suddenly, K, for so long morose and taciturn, reveals his love for Ojosan. The young Sensei is devastated to hear that the person he has been trying to help has turned into his rival for Ojosan’s affections. Sensei turns against K, doing all he can to outmanoeuvre him and, behind his back, asking for Ojosan’s hand in marriage. Then K commits suicide. But even the reasons for this are unclear. Is it because K has lost Ojosan, or that he has been betrayed by his friend, or that he is disappointed in himself? Or is it a combination of all of these? And if K’s suicide xvis ultimately a mystery, so, too, is Sensei’s. Even Japanese critics have been baffled by the notion of the “spirit of Meiji” to which Sensei claims allegiance and holds up as the impetus for his decision finally to commit suicide, for Sensei, living in idle seclusion from the world, appears to have very little in common with the Meiji era and its ethic of hard-working self-sacrifice and devotion to the nation state.

What Sōseki amply demonstrates with Kokoro is how a story with only three main protagonists in the first half—the narrator, Sensei and Shizu—and three in the second—Sensei, K and Shizu transformed into Ojosan—can have such tremendous psychological complexity. It seems that even within such a tight-knit circle our capacity to misunderstand our closest companions is almost infinite. Moreover, these complexities multiply over the passage of time as our very identities become transformed, and yet we remain in constant dialogue both with the actions of our former selves and with the dead. The narrative drives forward, utterly gripping and remorseless, and develops with a kind of seamless psychological inevitability as the young Sensei is caught between not wanting to act because he thinks he’s being tricked and then, when his jealousy is activated by K’s interest in Ojosan, not wanting to lose the woman he loves.

Kokoro, then, is a work that is at once simple and beautifully written and yet seems bottomless in its capacity for multiple interpretations. So how can we possibly get to the heart, kokoro, of what this mysterious novel is all about?

Permanently Evolving Ideas

To get to grips with Kokoro, we should consider the development of ideas in some of Sōseki’s earlier novels. The most appropriate xviplace to start is Sōseki’s 1910 novel The Gate. (This novel has recently been re-released as a Peter Owen Modern Classic, and interested readers are encouraged to read the critical introduction to that novel also.) In The Gate Sōseki provided a sympathetic portrayal of a childless couple living at the bottom of a cliff. The husband, Sosuke, hears that his former best friend Yasui—whose wife he has taken for himself—has dropped out of respectable society and become an “adventurer” in Manchuria. The friend is now briefly returning to Tokyo, and Sosuke, already worried about his wife’s illnesses and desperately fearful of encountering his former best friend, flees in desperation to a Zen temple, but there makes no progress and returns home disconsolate.

Although Sosuke is depicted with great realism, there is no question that the overall architecture of that novel is deeply satirical. The weak-willed Sosuke seeks respite in the world of Zen, yet Sōseki intimates that Zen is the greatest adventure of them all and only those with an iron will and the ability to be adventurous in their thinking will grasp its teachings and find the “way”.

Sōseki seems to have possessed what one of his friends referred to as a profoundly Hegelian frame of mind, always offering a reverse opinion to any notion put to him and offering an antithesis to any thesis. Each novel would emerge as a kind of natural contrast to the ideas and style of the previous work, and, indeed, no reverse in perspective is so marked as that which divides The Gate from Sōseki’s next novel To the Spring Equinox and Beyond (hereafter called Equinox)—and for good reason. After completing The Gate in July 1910, on 24 August that year Sōseki suffered a massive and near fatal attack of stomach haemorrhaging while staying at an inn at Shuzenji hot springs. After partially recovering from this Sōseki found himself taking stock of his life in a book of memoirs called Recollections, in which he recorded how surprised xviihe was to find illness had brought him a strange mental ease as well as making him the object of much care and attention from his friends.

Where The Gate had covertly encouraged the embrace of adventure, Sōseki now discovered the grim irony of being himself visited by the most dangerous thing he had ever encountered, and he found himself not to be strong, wilful and adventurous but, rather, weak, sickly and desperately grateful for the support and affection of those around him. The glorification of any kind of adventure, even of a self-effacing kind, must have appeared somewhat ludicrous to him after the Shuzenji incident. So, when Sōseki started writing Equinox he turned the whole thesis of The Gate comically on its head and put the emphasis on the way in which adventure can be degenerate. Sōseki opens Equinox with the adventurer Morimoto, whose tales are no more than those of a drunken ignoramus who drifts from place to place. He is never successful at anything, merely leaving debts behind when he absconds to Manchuria by the end of the first chapter. The adventure theme continues throughout Equinox, first in the frivolous, degenerate sense but then moving in an arc to a more thoughtful kind, which explores not distant countries or freak novelties but the inner lives of the people around us. The most worthwhile adventure, Sōseki concludes, is the exploration of the human heart, and it is this crucial theme that would be further developed in Kokoro.

In between Equinox and Kokoro, however, Sōseki wrote another novel, The Wayfarer, in which a man called Ichiro tries to persuade his younger brother Jiro to test the fidelity of Ichiro’s wife Nao. Ichiro wants Jiro to probe into Nao’s innermost heart by spending a night alone with her. Jiro initially refuses, but he and his sister-in-law are caught in a storm and forced to share a room at an inn. Jiro writes, “Out of nowhere welled up a thrill of joy at xviiithe rare adventure [italics added] I happened to be sharing with my sister-in-law.”

If Equinox is about the possibility of exploring the hearts of those around us, in The Wayfarer Sōseki emphasizes the reverse, that the hearts of other people may ultimately be impenetrable—time and again in The Wayfarer Ichiro fails to unearth his wife’s innermost secrets. Yet with the writing of Kokoro, as always Sōseki’s ideas began to turn towards a new question, as to whether, in fact, it is possible for one man to force his way into another’s heart and lodge himself there for ever.

The Stealing of a Man’s Heart

Many readers and critics have considered Sōseki’s depiction of Sensei in Kokoro to be entirely sincere, but there are strong hints that, actually, Sōseki was taking an ironical stance. Certainly, from the outset there are many echoes of his thoughts on irony from previous writings. For example, in his earliest work, “The Tower of London”, when looking at the inscriptions on the walls of the Beauchamp Tower the narrator remarks:

There is in the world a thing called irony. One says white and means black; one advocates small and suggests big. Among all ironies, there is none as fierce as the irony left unwittingly to posterity. Whether graves or monuments, whether medallions or cordons, these things are, so long as they exist, nothing more than a means of making one recall through a futile object bygone days.

The cold words remain on the walls of the tower, but the writers have disappeared. This sentiment is echoed in the opening pages of Kokoro. When the narrator accompanies Sensei on his monthly xixwalk to K’s grave he observes en route some of the elaborate inscriptions on the gravestones but doesn’t know how to read them. There seems something pointless about this attempt to be remembered through cold objects, and yet the memory of the mysterious person whose grave Sensei visits has somehow managed to live on in Sensei’s beating heart.

Kokoro fairly bristles with such subtle ironies. When, for example, the narrator returns to spend the summer with his parents and tells them about his esteemed friend Sensei, they assume he must be someone who is distinguished and capable of helping their son in his future career. The narrator’s mother insists that her son write to Sensei about his future prospects and eagerly awaits the reply, thinking that it will contain an introduction to someone who can offer her son a position, information with which she also hopes to console her dying husband. Yet when it actually does arrive, the letter from Sensei hardly mentions this matter at all; instead, in describing Sensei’s decision to commit suicide the letter actually tears her son away from his dying father’s side.

Sensei’s testament, too, is riddled with ironies. He relates how, as a young man, he tried to put new blood into his friend K by placing him in the company of the opposite sex, only for K to fall in love with the object of Sensei’s own affections. And K, for his part, makes the disastrous mistake of confessing his love to the one person who is his rival for Ojosan’s affection. Indeed, throughout his life, Sensei constantly claims that he is acting with a conscience and thinking about what is best for those closest to him—K, Shizu/Ojosan, the narrator—yet he manages to devastate all their lives in turn. First, he betrays K and, by taking away the object of his love, precipitates his suicide. Then he makes his wife’s life a misery, torturing her with the idea that she has done something wrong so causing a gulf between them, and ultimately inflicting xxhis death upon her. Finally, he commits suicide at the precise time that the narrator’s father is on his deathbed, so causing a terrible emotional crisis.

Unexpectedly, perhaps, we are not told anything about what happens to the narrator and Shizu after Sensei’s death. What did the narrator think after he read Sensei’s testament? How did he face Shizu? How did she cope with Sensei’s death? When did the narrator’s father die, and how did the narrator leaving his father’s bedside affect his relations with his family? Was there really, as Sensei feared, a battle over inheritance after the death of the narrator’s father? All of these things we have to imagine for ourselves, meaning that the narrative somehow seems to spin out into the future as if it has been violently interrupted. The open ending also hints at the impossibility of our ever reaching a definitive conclusion on people’s actions and motives, on uncovering what is hidden in their hearts. Ultimately, what the narrator thinks about Sensei after reading his testament remains a complete mystery.

Yet let us take a slightly closer look at this nameless character referred to as Sensei. Interestingly, the opening of the novel is imbued with a striking homoeroticism. When they first meet the narrator writes, “Sensei had just taken his clothes off while I was exposing my wet body to the wind”, and the two men then swim out into the sea and let their bodies float side by side in the warm water. There is an instant chemistry between them, and the narrator even senses that he has seen Sensei before. The narrator is looking for something, and, when disappointed by Sensei’s cool attitude, he keeps driving forward trying to find it. There is something unapproachable about Sensei, and yet it is precisely that something to which the narrator is drawn.

Out walking with the narrator, Sensei sadly advises him that their relationship is but a staging post in the young man’s development xxito heterosexual relations. Observing loving couples, Sensei remarks that love is a “sin” and then specifically compares their own relationship to one of these couples.

“Did you not come to me because you felt there was something lacking?”

“Perhaps. But that is a different thing to love.”

“It is a step towards love. As a preliminary to embracing the opposite sex, you have moved towards somebody of your own sex like me.”

“To me the two things seem totally different.”

“No, they’re the same. Because I am a man I simply cannot give you the kind of satisfaction you are looking for. Moreover, because of special circumstances, there is even less chance of me satisfying you. I really feel sorry about it. It’s inevitable that you will move away from me. In fact, that is what I’m hoping for.”

That word “satisfy” is a key one in Kokoro, occurring as it does with startling frequency. Sensei regrets that he cannot satisfy the narrator, just as the narrator’s answers to Shizu’s tortured questions about Sensei later fail to satisfy her. When the young narrator returns home to his parents, his tales of Tokyo satisfy his father, although the narrator cannot be satisfied with their games of chess together. The narrator tells us he is satisfied with his graduation essay but unsatisfied with Sensei’s explanations about his past. And there are many more such instances. In the same way, in “Sensei and His Testament” Sensei reveals that he was satisfied when K moved into his lodgings and everyone was satisfied with his success at showing K a world outside his own. But Sensei was not satisfied when he found K’s heart to be covered with black lacquer that wouldn’t allow a single drop of blood to be infused.

xxiiSo what exactly is Sensei’s agenda with the narrator? Sensei reveals that he will be satisfied only if he can completely transfer his heart to him. It soon becomes clear that all his life Sensei has been looking for someone to whom he can give his heart, to reveal his dark “secret”. And here Sōseki may have taken inspiration from a familiar source, for Kokoro shows some elements of similarity with one of Shakespeare’s plays, The Merchant of Venice, a work Sōseki spent a term analysing for his students at Tokyo Imperial University. Both works describe the melancholy love an older man bears for a younger man, to such an extent that the older man would cut out his own heart and give it to the younger man if only he felt he could successfully lodge it within the younger man’s breast. In The Merchant of Venice the contest for Bassanio’s heart is between the homosexual lover Antonio and the heterosexual lover Portia, and by the time of the trial scene, faced with the Jewish moneylender Shylock wanting to claim his pound of flesh, Antonio, far from making an impassioned defence of his life, seems only too willing to die for Bassanio. Antonio, it seems, has realized that by giving his life in this way—by quite literally having his heart cut out for Bassanio—he will be lodged in his heart for ever:

You cannot be better employ’d, Bassanio,

Than to live still, and write my epitaph. (IV. i)

As a Shakespeare scholar, Sōseki, who at the end of Equinox had made manifest his conclusion that the greatest adventure in life is the exploration of the human heart, The Merchant of Venice must have appeared redolent in suggestiveness. Just as Antonio welcomes having his heart cut out for his lover just so long as he will be remembered by him for ever, Sensei expresses himself to the narrator in Kokoro as follows:

xxiiiYou wanted to cut open my heart and lap up the warmly flowing blood. I was still alive then. I didn’t want to die. So, promising you another day, I turned down your request. Now I myself will tear open my own heart and attempt to bathe your face in that blood. And I will be satisfied if, when my pulse has stopped, a new life has lodged itself in your chest.

And when we encounter that word “Sensei” we should remember that in his early work “The Inheritance of Taste” Sōseki had written:

There is in the world a thing called satire. Satire always has two types of meaning, a surface meaning and a reverse meaning. Everyone knows that the word “Sensei” can be used to mean “fool”.

Thus, for us to be told at the beginning of this novel that a young man has decided to call someone “Sensei” and will refer to him by no other name, should our irony-detectors start twitching? Just because the narrator thought this character was worthy of being called “Sensei” does not, of course, mean that we, the readers, should necessarily think of him as being worthy of such a title. (Sōseki was himself surrounded by adoring young acolytes who all addressed him as “Sensei”, so he was well versed in the foibles of naive young men.)

Kokoro, in fact, reveals itself as the final, most sophisticated stage in the series of satirical antitheses that had been running throughout Sōseki’s previous novels. If in The Wayfarer we witnessed the ironic reversal of the would-be detective Ichiro being turned into the one who is observed, then in Kokoro we have the equally ironic situation of a young man attempting to understand xxivthe heart of the enigmatic “Sensei”, and in so doing ending up having Sensei’s very lifeblood transfused into him and his heart left no longer his own.

The young, naive narrator approaches Sensei in a similar way that the young character approaches Morimoto in Equinox, but we are soon told that Sensei, unlike the drunken Morimoto, is a man who generally drinks little: “He was a man incapable of such adventures as drinking a certain amount and, if not then drunk, carrying on drinking until getting drunk.” In other words, he is a much more subtle creation than the crude and boorish Morimoto in that earlier novel. The narrator in Kokoro persistently moves towards Sensei and tries to understand him but instead finds that “Sensei’s influence was entering into his head, flesh and blood”. Sensei, for his part, acts almost like a jealous lover and keeps checking that the narrator won’t abandon him. He constantly worries that the narrator’s current reverence will be transformed into derision in the same way that Sensei once knelt in front of K before metaphorically putting the knife into him. And, indeed, perhaps this fear is justified, for the narrator does ultimately betray Sensei by publishing his story while his wife is still alive, in spite of Sensei’s last request that he not do so.

Whatever the surface nature of things in Kokoro, however much Sensei might say he has chosen to die to redeem the guilt of K’s death and to indulge in junshi like General Nogi, these are all but superficialities. They play exactly the same masking role in Kokoro as Shylock’s bond and anti-Semitism do in The Merchant of Venice. They are like Portia’s glittering caskets: they deceive the eye, but they are valueless inside. The real story of Kokoro lies elsewhere.

Kokoro is, first and foremost, about the means of transferring permanently one’s heart into the breast of another. In the novel the means of doing this is through a carefully staged death—no xxvone knows better than Sensei how well K has succeeded in seizing for all eternity Sensei’s heart through suicide, and Sensei sets out to grasp the narrator’s heart for ever in exactly the same way. And how well he succeeds. The whole text of Kokoro becomes the narrator’s epitaph to Sensei.

At the beginning of the novel the narrator says that he will not refer to Sensei with a mere letter, as Sensei in his testament refers to K, because this is too “cold”. As discussed, this has inspired much debate in Japan, but the significance of this is surely to emphasize that the bond between Sensei and the narrator is even stronger than that which existed between Sensei and K. And when at the end of Sensei’s long testament he asks the narrator that his secret is not made public while Sensei’s wife still lives—and it is implied that she is still alive when the story is being told—the point of the story being made public is also, perhaps, to show that the love bond between Sensei and the narrator is being held up as more important than any commandment regarding Sensei’s wife.

We should certainly not believe those old-fashioned critics who want to convince us that Sōseki in Kokoro was rhapsodizing about the end of the Meiji era. Their misunderstanding of this classic novel is as absolute as those generations of critics who argued about the anti-Semitism in The Merchant of Venice. They miss the point entirely. Things on the surface are very different from the heart contained within. For Kokoro is a battleground over love, and Sensei is a man who is prepared to die—give up his heart—to see it transferred for ever into the breast of another man.

Damian Flanagan

All translations from the Japanese in the Introduction are by Damian Flanagan.xxvi

KOKORO

xxviii

SENSEI AND I

Ialways called him “sensei.”1 I shall therefore refer to him simply as “Sensei,” and not by his real name. It is not because I consider it more discreet, but it is because I find it more natural that I do so. Whenever the memory of him comes back to me now, I find that I think of him as “Sensei” still. And, with pen in hand, I cannot bring myself to write of him in any other way.

It was at Kamakura, during the summer holidays, that I first met Sensei. I was then a very young student. I went there at the insistence of a friend of mine, who had gone to Kamakura to swim. We were not together for long. It had taken me a few days to get together enough money to cover the necessary expenses, and it was only three days after my arrival that my friend received a telegram from home demanding his return. His mother, the telegram explained, was ill. My friend, however, did not believe this. For some time his parents had been trying to persuade him, much against his will, to marry a certain girl. According to our modern outlook, he was really too young to marry. Moreover, he was not in the least fond of the girl. It was in order to avoid an 2unpleasant situation that instead of going home, as he normally would have done, he had gone to the resort near Tokyo to spend his holidays. He showed me the telegram, and asked me what he should do. I did not know what to tell him. It was, however, clear that if his mother was truly ill, he should go home. And so he decided to leave after all. I, who had taken so much trouble to join my friend, was left alone.

There were many days left before the beginning of term, and I was free either to stay in Kamakura or to go home. I decided to stay. My friend was from a wealthy family in the Central Provinces, and had no financial worries. But being a young student, his standard of living was much the same as my own. I was therefore not obliged, when I found myself alone, to change my lodgings.

My inn was in a rather out-of-the-way district of Kamakura, and if one wished to indulge in such fashionable pastimes as playing billiards and eating ice cream, one had to walk a long way across rice fields. If one went by rickshaw, it cost twenty sen. Remote as the district was, however, many rich families had built their villas there. It was quite near the sea also, which was convenient for swimmers such as myself.

I walked to the sea every day, between thatched cottages that were old and smoke-blackened. The beach was always crowded with men and women, and at times the sea, like a public bath, would be covered with a mass of black heads. I never ceased to wonder how so many city holiday-makers could squeeze themselves into so small a town. Alone in this noisy and happy crowd, I managed to enjoy myself, dozing on the beach or splashing about in the water.

It was in the midst of this confusion that I found Sensei. In those days, there were two tea houses on the beach. For no particular reason, I had come to patronize one of them. Unlike those people with their great villas in the Hase area who had their own bathing 3huts, we in our part of the beach were obliged to make use of these tea houses which served also as communal changing rooms. In them the bathers would drink tea, rest, have their bathing suits rinsed, wash the salt from their bodies, and leave their hats and sunshades for safekeeping. I owned no bathing suit to change into, but I was afraid of being robbed, and so I regularly left my things in the tea house before going into the water.

Sensei had just taken his clothes off and was about to go for a swim when I first laid eyes on him in the tea house. I had already had my swim, and was letting the wind blow gently on my wet body. Between us, there were numerous black heads moving about. I was in a relaxed frame of mind, and there was such a crowd on the beach that I should never have noticed him had he not been accompanied by a Westerner.

The Westerner, with his extremely pale skin, had already attracted my attention when I approached the tea house. He was standing with folded arms, facing the sea: carelessly thrown down on the stool by his side was a Japanese summer dress which he had been wearing. He had on him only a pair of drawers such as we were accustomed to wear. I found this particularly strange. Two days previously I had gone to Yuigahama, and sitting on top of a small dune close to the rear entrance of a Western-style hotel I had whiled away the time watching the Westerners bathe. All of them had their torsos, arms, and thighs well-covered. The women especially seemed overly modest. Most of them were wearing brightly colored rubber caps which could be seen bobbing conspicuously amongst the waves. After having observed such a scene, it was natural that I should think this Westerner, who stood so lightly clad in our midst, quite extraordinary.

4As I watched, he turned his head to the side and spoke a few words to a Japanese, who happened to be bending down to pick up a small towel which he had dropped on the sand. The Japanese then tied the towel around his head, and immediately began to walk towards the sea. This man was Sensei.

From sheer curiosity, I stood and watched the two men walk side by side towards the sea. They strode determinedly into the water and, making their way through the noisy crowd, finally reached a quieter and deeper part of the sea. Then they began to swim out, and did not stop until their heads had almost disappeared from my sight. They turned around and swam straight back to the beach. At the tea house, they dried themselves without washing the salt off with fresh water from the well, and, quickly donning their clothes, they walked away.

After their departure I sat down, and, lighting a cigarette, I began idly to wonder about Sensei. I could not help feeling that I had seen him somewhere before, but failed to recollect where or when I had met him.

I was a bored young man then, and for lack of anything better to do I went to the tea house the following day at exactly the same hour, hoping to see Sensei again. This time, he arrived without the Westerner, wearing a straw hat. After carefully placing his spectacles on a nearby table and then tying his hand towel around his head, he once more walked quickly down the beach. And when I saw him wading through the same noisy crowd, and then swim out all alone, I was suddenly overcome with the desire to follow him. I splashed through the shallow water until I was far enough out, and then began to swim towards Sensei. Contrary to my expectation, however, he made his way back to the beach in a sort of arc, rather than in a straight line. I was further disappointed when I returned, dripping wet, to the tea house: he had already dressed, and was on his way out.5

I saw Sensei again the next day, when I went to the beach at the same hour; and again on the following day. But no opportunity arose for a conversation, or even a casual greeting, between us. His attitude, besides, seemed somewhat unsociable. He would arrive punctually at the usual hour, and depart as punctually after his swim. He was always aloof, and no matter how gay the crowd around him might be he seemed totally indifferent to his surroundings. The Westerner, with whom he had first come, never showed himself again. Sensei was always alone.

One day, however, after his usual swim, Sensei was about to put on his summer dress which he had left on the bench, when he noticed that the dress, for some reason, was covered with sand. As he was shaking his dress, I saw his spectacles, which had been lying beneath it, fall to the ground. He seemed not to miss them until he had finished tying his belt. When he began suddenly to look for them, I approached, and bending down, I picked up his spectacles from under the bench. “Thank you,” he said, as I handed them to him.

The next day, I followed Sensei into the sea, and swam after him. When we had gone more than a couple of hundred yards out, Sensei turned and spoke to me. The sea stretched, wide and blue, all around us, and there seemed to be no one near us. The bright sun shone on the water and the mountains, as far as the eye could see. My whole body seemed to be filled with a sense of freedom and joy, and I splashed about wildly in the sea. Sensei had stopped moving, and was floating quietly on his back. I then imitated him. The dazzling blue of the sky beat against my face, and I felt as though little, bright darts were being thrown into my eyes. And I cried out, “What fun this is!”

After a while, Sensei moved to an upright position and said, “Shall we go back?” I, who was young and hardy, wanted very 6much to stay. But I answered willingly enough, “Yes, let us go back.” And we returned to the shore together.

That was the beginning of our friendship. But I did not yet know where Sensei lived.

It was, I think, on the afternoon of the third day following our swim together that Sensei, when we met at the tea house, suddenly asked me, “Do you intend to stay in Kamakura long?” I had really no idea how much longer I would be in Kamakura, so I said, “I don’t know.” I then saw that Sensei was grinning, and I suddenly became embarrassed. I could not help blurting out, “And you, Sensei?” It was then that I began to call him “Sensei.”

That evening, I visited Sensei at his lodgings. He was not staying at an ordinary inn, but had his rooms in a mansion-like building within the grounds of a large temple. I saw that he had no ties of any kind with the other people staying there. He smiled wryly at the way I persisted in addressing him as “Sensei,” and I found myself explaining that it was my habit to so address my elders. I asked him about the Westerner, and he told me that his friend was no longer in Kamakura. His friend, I was told, was somewhat eccentric. He spoke to me of other things concerning the Westerner too, and then remarked that it was strange that he, who had so few acquaintances among his fellow Japanese, should have become intimate with a foreigner. Finally, before leaving, I said to Sensei that I felt I had met him somewhere before but that I could not remember where or when. I was young, and as I said this I hoped, and indeed expected, that he would confess to the same feeling. But after pondering awhile, Sensei said to me, “I cannot remember ever having met you before. Are you not mistaken?” And I was filled with a new and deep sense of disappointment.

7I returned to Tokyo at the end of the month. Sensei had left the resort long before me. As we were taking leave of each other, I had asked him, “Would it be all right if I visited you at your home now and then?” And he had answered quite simply, “Yes, of course.” I had been under the impression that we were intimate friends, and had somehow expected a warmer reply. My self-confidence, I remember, was rather shaken then.