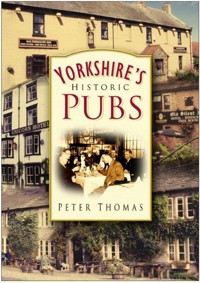

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

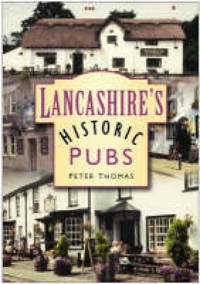

If you enjoy the occasional pub meal, a drink at the bar, or if you're interested in Lancashire's social history, you're sure to find something entertaining in Peter Thomas's introduction to the county's pubs. It opens with a round-up of the history of brewing, pubs and ale-selling, and a section on Lancashire's pub signs, though most of the book is dedicated to an A-Z of over fifty of the most interesting inns. Their history, architecture, ghosts and associated legends are all featured, as well as the exploits of their famous and infamous landlords and landladies. Peter's exhaustive research has resulted in a gem of a book which brings together the proud history, traditions and customs associated with Lancashire hostelries; from ale tasting at the Plough at Eaves to the Britannia Coconut Dancers at the Crown Inn at Bacup. A fascinating journey, with plenty of refreshment stops along the way, this will appeal to anyone with an interest in local history, and those who'd like to know more about the convival surroundings in which they might enjoy a pint.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 265

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2006

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

LANCASHIRE’S

HISTORIC

PUBS

PETER THOMAS

One of the tenth-century Celtic crosses at Whalley (see p. 92).

First published in 2006 by Sutton Publishing

Reprinted in 2010 by

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Reprinted 2011

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Peter Thomas, 2010, 2013

The right of Peter Thomas to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5435 8

Original typesetting by The History Press

A short distance from the Redwell Inn at Arkholme is the delightful river walk along the Lune at Kirkby Lonsdale.

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Pubs, A–Z

Acknowledgements

The exterior of the Old Man & Scythe at Bolton.

The packhorse bridge and church at Croston.

Author’s Note

Readers will have noticed with sorrow the closure of many pubs, a few of which are featured in this book.

For regulars their local became a meeting place for the community and a news exchange to be enjoyed over their drinks and meals.

Landlords grew to know their customers through their days and times, as well as their orders. One I remember most warmly knew one of his regulars was losing his sight and was having a problem crossing the busy road to the pub. Who but the landlord used to bring him safely across the road?

The history of a pub, sometimes very ancient, shows in its architecture. Whatever the building is and does today, it is worth going to see.

See and enjoy: go in if it’s open!

INTRODUCTION

The pub is so much part of our tradition that, like the village green or the marketplace, it seems to have been with us throughout our history. Yet it was not always as it is now, neither was it originally called a public house; today’s ‘local’, however small, is licensed and regulated, a far cry from the early drinking houses where home-brewed ale was sold.

Scraps of evidence tell us that barley was being grown in England long before the Romans came; their writers suggest that an intoxicating drink was already being produced here through the soaking of grain. How much earlier is difficult to say, but one can imagine that the knowledge of how to brew and the attractive product would have been eagerly passed on. This would, of course, have been a domestic brew consumed at home; perhaps if there was a surplus it was bartered or sold.

The Roman tabernae, or drinking places, in their settlements and along the many miles of Roman roads, mark the first use of the word ‘tavern’ that we can recognise in our day. The Romans distinguished these premises with a bunch of vine leaves outside; wine was the most common drink, although ale was sold as well. Apart from this, we have the voice of the Christian Church condemning drunkenness to tell us that there was much excessive drinking. In the eighteenth century the Archbishop of York ruled that priests should not eat or drink in taverns.

The so-called Dark Ages and the reigns of Saxon kings saw the establishment of ale-houses and taverns that was to lead to today’s public houses. The number grew rapidly, selling mostly home-brewed ale and mostly run by women, known as brewsters or ale-wives.

By the 1300s ale selling was still on a very small scale. We can safely conclude that the accommodation was only the ale-house kitchen and the only facility a warm fire. Because of the limitations, most sales must have been off the premises. Because there was so much poverty it was very likely that some ale-wives were driven to brewing and selling ale from necessity; they could possibly earn a little at harvest time, or when the price of barley made brewing worth while.

With an increase in the population and better wages, a rising demand gave ale-houses selling a good ale an opportunity to grow; food and social activities began to be offered, especially in towns. To mark these permanent ale-houses the use of ale-stakes – a pole with a bush at the end – became common and was soon made a requirement. In the 1400s the official licensing of ale-houses was introduced. By then the pattern of England’s drinking houses was becoming clear:

Inns These were the smallest in number, but largest in size, with the best standard of accommodation and widest range of food and drink. When coach travel brought passengers who needed overnight accommodation, it was the inns that provided it and offered stabling for horses. These coaching inns are easily recognised even today; an example is the Coach & Horses at Whitefield.

Inns became the focus for the social life of wealthy residents. They were the venues for balls and assemblies so beloved of Jane Austen’s characters, and places where the local hunt would meet. Their size (often the largest building in the area after the church) made them suitable for business and council meetings; their locations encouraged their use by carriers for collections and deliveries. Their courtyards, stables and outbuildings made excellent commercial sense. Because of their quality, style and size, many of them were able to continue, successfully retaining their traditional role as inns. Others, aspiring to higher things, adopted the title ‘hotel’. Either way, this was the quality end of the market.

Taverns Lower down the social order and providing drinking facilities for upper-middle-class customers, taverns sold wine and basic food, but rarely offered accommodation. Once the railways had arrived the place of taverns in the scheme of things would be clearer with neighbouring establishments known respectively as the Station Hotel and the Station Tavern.

Taverns had a good deal of competition from higher-quality ale-houses and from coffee-houses in their age of popularity; eventually numbers began to fall and they began to lose a separate identity. By 1800 few taverns could be distinguished from ale-houses.

By the eighteenth century there was little difference between smaller inns, taverns and ale-houses. At the same time a new name began to cover most of this group: the ‘public house’, possibly through some sort of recognition of its place as a ‘public ale-house’. This would have acknowledged its uniqueness as a private home, yet open to the public for the sale of ale. From the earlier, primitive one room and fire, many pubs, especially in towns, provided a parlour and a bar, vault or taproom. Social activities now increased, both in the pub and outside.

Ale-houses and early pubs had a very limited range of drinks, mainly ale, although cider and perry, for example, were available in districts in the west of England. The introduction of hopped beer from Flanders altered all that; the first recorded beer import was in 1400 in Sussex and its popularity quickly spread, particularly in the south. By 1600 beer had replaced ale in most pubs; the introduction of hops to the usual brewing ingredients of water, malt and yeast allowed a wide variety of flavours and strengths to be produced.

The brewing of beer was well suited to large-scale production, encouraging commercial brewing and giving a cheaper product. In the north, ale-house keepers continued to make their own drink for longer than in the south, but change was bound to come, not least because in its keeping properties beer had a longer product life than ale. In later years an unusually large quantity of hops was used for beer brewed for export: IPA (India Pale Ale) was a beer brewed in this way especially to take advantage of the preservative effect of the hops. Greene King Brewery had in mind the long sea voyage to India, where in the days of empire there was a big British expatriate market and a strong thirst! Eventually only the lightly hopped drink continued to be called ale, while the more heavily hopped version was called beer. There is no such distinction today.

Pub signs and their meaning

We have seen how a bunch of vine leaves or an ale-stake was once a sign denoting a drinking place. This was not only a convenience for travellers, but ensured that the premises were visited by the official ale-taster or ale-conner, whose duty was to test the quality and price of ale sold there. An ale-garland in the form of a wreath of flowers was added when a new brew needed the ale-conner’s inspection.

Ale-house windows were often covered by lattice work or trellis, usually painted red: going back as far as the days of Elizabeth I these were a clear sign of an ale-house, but have long since ceased to be used for the purpose.

As the number of ale-houses increased, so the need to distinguish one from another for reasons of competition became stronger. From the simplest painted sign fixed to the front wall to elaborate hanging signs sometimes mounted in patterned wrought iron, the range is enormous. In medieval times and earlier few people were literate, so the name of the landlord or the ale-house on the sign would have been of little help; the reason for many of the ale-houses’ chosen names is often obscure, but a fascinating study.

The most common names and signs today are thought to be: Red Lion, Rose and Crown (or Crown) and Royal Oak. At the White Bull at Ribchester there is a reproduction white bull prominently displayed high up in addition to a painted hanging sign, while a bunch of grapes on the front of the Swan and Royal at Clitheroe is a reminder of the vine leaves once used to mark drinking houses and the quality of the drink sold there.

Sad to say, very few examples remain of the spectacular ‘gallows’ signs that once stretched right across the road like football posts and crossbar. One by one they were demolished because of the expense of maintenance and the danger to passers-by. The most remarkable was that at the White Hart, Scole, now the Scole Inn, near Diss in Norfolk, erected in 1655 and held to be ‘the noblest signe-post’ in the country.

A fine survivor is at Barley on the Hertfordshire/Cambridgeshire border where at the Fox & Hounds a beam crossing the road carries on it the hunt in silhouette, showing the huntsmen closing in on the fox. Another once thought lost for ever has recently been replaced after a long fight. Brought down by a high-sided vehicle, the Magpie sign that crossed the A140 Norwich road at Stonham in Suffolk is back in all its glory; some of us may recall that the original carried the Brewery’s name ‘Tolly’ below the bird. Such is everyone’s satisfaction and pleasure in a battle won, the replacement Magpie alone on its new beam has been welcomed back unreservedly.

No mistaking the White Hart at Scole, near Diss in Norfolk, now the Scole Inn! The landlord must have been desperate to impress his guests to have been willing to pay £1,000 in 1655 for this elaborate sign. The whole structure is loaded with extravagant carving and has twenty-five life-size figures; in the centre of the arch is the white hart from which the inn originally took its name. The present sign is handsome and hangs over the road, but was far less costly.

The Magpie sign at Stonham in Suffolk is more basic than that at Scole, but is well loved locally. The pub and sign photograph well together, but patience is needed to capture a good moment and care as well, as the A140 traffic moves fast.

Ale-tasting: the tradition today

Everyday life in medieval England was originally administered through courts based on the historic manors around which settlements, including market towns, grew.

Henley-in-Arden in Warwickshire has one of the very few remaining manorial courts: its Court Leet. Today it represents little more than tradition and civic dignity, but its annual election of officers in November and its long record of their responsibilities and functions is a vital part of Henley’s identity. Had it not been for Henley’s ability to prove regular meetings of the Court Leet and Court Baron over many years, an Act of Parliament in 1976 would have abolished them, and the ale-tasting tradition as well.

The Henley Ale-taster is one of the Court’s officers with robe and badge that have always marked the importance of his office. The first record of the Court in Henley was in 1333, but of special interest is a written statement of the Taster’s duties dated 13 October 1593:

We order that all the Ale Howse Kepers and Victelers within the liberties shall make good and holsome ale and beare for mans bodie and that they and every one of them sell the same for two pence half penny a gallon new and three pence stale and everyone denying to sell as aforesaide shall forfett for every offence XIId.

Henley’s charter dates back to 1220, when Henry III granted Peter de Montfort, Lord of the Manor, the right to hold a weekly market and an annual fair at the feast of St Giles (1 September).

Giles was born at Athens; after the death of his parents he went to France, where he led the life of a hermit in a cave near the mouth of the river Rhone. After building a monastery there he became its first abbot. He was patron of cripples, lepers and nursing mothers; his churches (well over 100 were dedicated to him in England) are often at crossroads so that travellers halting for refreshment or for their horses to be shod could pray at church for a safe journey.

In the thirteenth century it was the custom on a market or fair day for the members of the Court Leet at Henley to parade around the town to warn all rogues, vagabonds and idle and disorderly persons to depart. They were to remain at their peril. Other courts existed at Alcester, Bromsgrove and Warwick so alternatives for the undesirables were limited. A very close relationship exists between these courts today, and invitations are exchanged welcoming representatives to their respective events.

Ale-tasting at Henley follows a ceremonial on a prearranged May evening; members of the Court Leet assemble and walk, robed, down the mile-long High Street, visiting in turn the eight pubs remaining there. There were double that number when the present Ale-taster was a schoolboy. At each pub the members of the Court are offered a half-pint of ale, which the Taster sips, pauses, considers carefully, then sips again, pronouncing meanwhile on the essentials such as flavour and colour.

Rivington Hall.

The Taster says that the ceremonial follows a well-established script. In conclusion, the licensee is presented with a certificate of satisfaction and the Court moves on to the next pub. It sounds like a pleasant social occasion, perhaps a deserved compensation for the time devoted by the Court members to their various duties. An additional Ale-taster has been appointed at Henley, allowing for an increase in the membership of the Court Leet.

The description of ale tasting given on pp. 170–3 under the Plough at Eaves may be closer to history as it really was than the highly coloured version of today at Henley-in-Arden. But the contrast between the ‘breeches test’ as at the Plough and the ceremonial at Henley is only to be expected; after all, much time has passed and much else has changed, too.

AFFETSIDENEAR BURY: THEPACKHORSE

Affetside: M60 to J15, Bolton A676 to Edgworth–Tottington crossroads. Turn sharp right for Affetside; or M60 to J18, M66 to J2, Bury A58 west along ring road. Turn right on to B6213 towards Tottington and fork left almost immediately for Affetside.

Little need for a postcode for this pub. What a historic address: 52 Watling Street! That was the name of the Roman road that ran all the way from the Romans’ landing place at Richborough in Kent to Wroxeter near Shrewsbury and passed through Affetside on the stretch between Manchester and Ribchester, where there is a crossing of the Ribble.

This important road, built by the legions, was increasingly used as the centuries passed by merchants who needed to move goods such as cloth for sale at distant markets. Packhorse trains would have toiled up the hills here; Affetside stands on the highest local point, so the appropriately named Pack Horse was well located to provide shelter and refreshment for travellers. Today’s visitors come by car and can linger to enjoy marvellous distant views such as Winter Hill.

Successive landlords of the Pack Horse have needed to increase their dining space. Apart from the main lounge bar at the front, there is a games room with dining tables near the entrance and a ‘snug’ by a side bar; access through the side bar allows diners to go through to two more dining rooms at the rear where the kitchen is located. At weekends every table is taken.

Standing on the Roman Watling Street, the Pack Horse has provided refreshment for travellers for hundreds of years.

A feature at the Pack Horse which is remembered by everyone who visits it is the skull which is on a shelf at the back of the main bar. Bizarre and gruesome, it is that of George Whewell (variously spelt), a local man whose family was massacred by Royalist soldiers commanded by James, 7th Earl of Derby, at the time of the siege of Bolton during the Civil War.

An account in the form of a poem at the Pack Horse tells of the Royalists’ defeat by Cromwell at Wigan, then again at Worcester, after which the King and Derby fled. The Earl was captured at Chester, tried and sentenced to death. He was sent back to Bolton where so many had died at the hands of the soldiers: Whewell volunteered as an executioner and gained his revenge.

One explanation of the display of Whewell’s skull in the pub is that the Royalist soldiers came back to make him pay for executing their commander. His skull was said to have been displayed outside to warn everyone; eventually it was taken inside, where it remains. Needless to say there are numerous stories describing the horrific experiences of people who attempted to move the skull out of the Pack Horse. In publicity terms, the skull is better than the usual ghost only seen by a few select believers; the skull is there for all to see. It is also well positioned to see what is going on at the bar: just try to forget it is there!

The Affetside Cross.

Across the road and no more than 50 yards away there is evidence of the village’s history. To celebrate the year 2000 a Millennium Green has been established, including a garden with pool and ducks: a so-called ‘breathing space’ with public footpaths giving people an opportunity to wander. The Rotary Clubs of Bolton have promoted a 50-mile circular walk, ‘The Rotary Way’. A notice announces the start of Stage 1, from Affetside to Little Lever, 5⅜ miles.

By the roadside nearby, facing a row of cottages, is the Affetside Cross. Heavily pitted, it stands on a plinth consisting of two circles of huge stones fastened together with metal straps. The shaft has a socket cut into the top which originally probably supported a cross, now lost; it would have served as a market cross for Affetside and district, and was possibly a place for preaching and public proclamations. This form of standing cross would have been quite common in medieval villages, but most were destroyed during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, making the Affetside Cross a relatively rare survival. It is listed as an Ancient Monument, and tradition dates it as Roman, possibly because it marks the line of the Roman road. It may be Saxon or even medieval; both are more likely than Roman. A continuation of Watling Street can be seen north-west of Edgworth, but there is no cross on that length. The cross at Affetside is said to have a special significance as it is exactly half-way between London and Edinburgh.

One wonders how much that half-way position really matters – except perhaps to the people of Affetside. What does matter is transportation in such a scattered landscape, both public and private. There is a bus service to and from Bolton and there are parking bays on the narrow Watling Street close to the Millennium Green and the Affetside Cross. For patrons of the Pack Horse there is a good car park, excellent food and, of course, the famous skull of George Whewell.

ARKHOLME (KIRKBY LONSDALEROAD)THEREDWELLINN

A6 or M6 north to Carnforth. Turn east on B6254, Market Street, leading into Kellet Road and Kirkby Lonsdale road. The pub is beyond Over Kellet.

Why the official address of the Redwell Inn is given as Arkholme is one of life’s mysteries. Perhaps it is something to do with the postcode. Don’t look for it in the village, as it isn’t there; watch for it on the Kirkby Lonsdale road well on the way to Over Kellet. There will be plenty of cars at the front, such is the pub’s popularity; fortunately there is plenty of space. Its sign is eye-catching, brilliantly glowing and illustrating the pub’s red well from which it takes its name.

By early evening the pub car park was filling rapidly, a sure sign of the popularity of the Redwell Inn.

Like so many country pubs that have a long history, the Redwell was once a farm as well as an inn. The building goes back to the seventeenth century and later served travellers as a coaching inn: the archway on the front is evidence of that, as are the outbuildings at the rear, which would have been stables. A barn was often an extension to these farmhouse inns and was so here, but is now converted into a handsome, spacious dining and function room.

Food is the focus here. Choose your evening according to its speciality: Monday is steak night, Thursday is duck night, Friday is fresh fish night and so on. Food is on offer every day from 12 to 9 p.m.; one of the most popular dishes is Cumbrian roast lamb.

Well before eating out in the evenings became regular and car travel made it easy, the Redwell was an important place for people to meet socially and, of course, to drink together. It had an official function, too, as a courthouse, and served business as an auction room.

The present landlady at the Redwell, Julie, has recorded a number of stories or legends connected with the pub. Sadly this is all too rare, and when the story tellers are no longer around the stories may be lost for ever. She mentions the return visit of a former German prisoner of war who worked at the Redwell during the Second World War; he spoke highly of his treatment and how well he was fed.

Of past landlords, Matt Slaughter seems to have been ready to ignore food regulations in 1945. He became famous for his quick thinking when police came to inspect the premises in the belief that he was trading bacon when it was rationed. They didn’t find the pig they thought was involved, as Matt had put it in bed with his wife!

A really poignant legend is that of Jack and Bess, the Redwell version of the willow-pattern plate story. It was 1685 when the Redwell stable boy Jack was found to be having a secret love affair with Bess, the daughter of the local master of the hunt. In spite of several warnings as to the serious consequences if Jack did not end the relationship, love seems to have been too strong and the affair continued.

The master of the hunt was known to be a heavy drinker and of a cruel disposition. One night when cock fighting was going on in the cellar at the Redwell and he was present, having had plenty to drink, news was brought to him that Jack and Bess had been seen. He ordered his men out, caught the lovers together and had Jack tied up. Despite Bess’s distress and pleas to her father, a large fire was built and Jack was burned at the stake. The message to poor Bess was ‘you are not to marry below your class and a gentleman of fine standing will be found for you’.

It is said that the experience of seeing Jack’s death robbed Bess of the power of speech and she sobbed continually for twelve months before dying of a broken heart at the age of eighteen. On a clear night under a full moon Jack and Bess can be seen walking hand in hand down the lane by the Redwell Inn whispering their love for each other. The story ends by saying that they will not notice you: they have eyes only for each other.

The well giving the Redwell its name is still there under a modern cover close to the back of the pub. For some unknown reason way back in the past the well water is said to have suddenly turned red; the easiest explanation at the time was witchcraft. Today we would look for some change in the soil through which the water filtered.

Certainly, like the famous Chalice Well at Glastonbury, the water at the Redwell gained the reputation of having strange healing properties. A recent letter received at the pub from a lady in Canada aged ninety-one confirms this.

The well that gave the pub its name.

As a baby barely a year old she became seriously ill with what sounds like pneumonia. When the doctor came he told the family that she was dying and would not see the night out. With nothing to lose, and led by her grandmother, the ladies of the house drew water from the well, warmed it on a stove and put it in a pan by the baby’s bed. A towel was spread in the water, the baby was laid on the towel and she was bathed and soaked in the warm water. The ladies worked all night keeping the baby warm and clearing mucus from her nose and throat with a goose feather dipped in goose grease.

Next morning there was laughter and tears: the baby was well and is living ninety years on. She says now that her life was saved entirely because of the power of Redwell water and that it has always helped to build healthy teeth and bones for children there. One of these days perhaps the mystery of the red well will be solved, but if not, we have a ninety-year-old story with a happy ending.

The base of the ancient market cross close to the church at Arkholme.

Arkholme village is worth a visit – even Kirkby Lonsdale is only 4 miles further on. Turn at the Arkholme crossroads down to the river Lune and the church. There is no through traffic so the peace and quiet allows visitors to admire the stone cottages, Georgian houses and delightful gardens. The beautiful little church stands by an ancient earthwork above the river and the remains of the old market cross are by the south side of the church.

The river Lune below Arkholme church. Along the riverside walks are willow trees that once provided material for the village’s cottage industry, basket making.

Past the Ferryman’s house a track leads quickly down to the riverside and its walks. This was the source of material, willow, for Arkholme’s traditional cottage industry, now gone: basket making.

Stay on long enough for time to go to Kirkby Lonsdale, which affords wonderful views of the Lune valley.

John Ruskin, who knew a thing or two about the countryside, called it ‘one of the loveliest scenes in England – therefore in the world’. The artist J.M.W. Turner painted the scene from a point close to the church there. They can’t both be wrong!

BACUPANDTHE COCONUTTERS: THECROWNINN

M60 to J18, M66, A56, A681 via Rawtenstall; or M65 to J8, A56, A681 via Rawtenstall.

The father with a little boy asked ‘Have the Nutters gone past yet?’ There were people waiting about, some for buses, others looking anxiously at watches, so possibly something was expected. The father and son relaxed.

It was on St James Street near the library in the centre of Bacup on the Saturday of Easter weekend. Then the penny dropped. This is the one day in the year when the Britannia Coconut Dancers come to town to perform their ancient dances at every Bacup boundary – and at all the pubs on the way. If the number of pubs really matters, some say ‘about twelve’, others ‘probably fifteen’. Since the Nutters get free beer at all of them, perhaps some uncertainty about the exact number is understandable. The Nutters say that they lose a lot of body fluid walking and dancing many miles and need to replace it!

As the crowds grew that day, including groups with walking boots and backpacks – certainly not locals – and many young people whose interest would usually be in something ‘cool’ rather than in tradition, the Britannia Coconut Dancers were a unique spectacle. But what makes these men of mature age black their faces so that the Devil cannot recognise them, don white hats decorated with red, white and blue rosettes, black jerseys, red-and-white kilts, white stockings and black Lancashire clogs?

They go on to perform dances accompanied by members of Sacksteads Silver Band and collect for charity. Ask one of the Nutters why they do it and keep to the same route every year. ‘It has always been so; it is a way of life.’ Their leader, Richard Shufflebottom, joined the Coconutters at age twenty-two; he retired in 2005 after fifty years. The Secretary, Joe Healey, has a tattoo on his arm that says ‘Coconutter Born & Bred’.

More about the Coconutters later, but with their experience, surely a re-commendation of a Bacup pub for inclusion in this book would be very simple. But nothing ever is. Remember the free beer for them at every pub along the way? This poses a diplomatic problem, the only solution being careful detective work to find a way forward.

The Coconutters in action.

The Crown Inn, Bacup. Don’t look for an inn sign under the ivy – there isn’t one.

Every weekend from Easter to September the Coconutters are out and about dancing at carnivals, folk festivals and charity functions of all kinds. Where are they to be found when they are back home, have washed off their black and have taken off their ‘gear’? Answer: at the Crown, which they seem to have made their own, bringing their wives and partners, also adding their own special brand of togetherness to the friendly informality of hosts Trevor and Kathy. A powerful combination!

Do not give up on your search for the Crown. There is no sign on the hill climbing out of Bacup along Yorkshire Street; look for Greave Road, fork right here and watch for a pub with no sign on the wall. A few parked cars give a clue, but the only other evidence is a tiny notice in a window partly hidden by ivy; all it says is Crown Inn, Greave Road, Bacup. Mon-Fri 5 p.m., Sat & Sun 12 noon. East Lancs Pub of the Year 2003 CAMRA.