Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: idb

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Once upon a time—which, when you come to think of it, is really the only proper way to begin a story—the only way that really smacks of romance and fairyland—all the Harmony members of the Lesley clan had assembled at Cloud of Spruce to celebrate Old Grandmother’s birthday as usual. Also to name Lorraine’s baby. It was a crying shame, as Aunt Nina pathetically said, that the little darling had been in the world four whole months without a name. But what could you do, with poor dear Leander dying in that terribly sudden way just two weeks before his daughter was born and poor Lorraine being so desperately ill for weeks and weeks afterwards? Not very strong yet, for that matter. And there was tuberculosis in her family, you know.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 467

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

* An idb eBook *

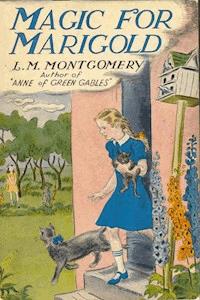

Magic for Marigold

L. M. (Lucy Maud) Montgomery (1874-1942)

Magic for Marigold

L. M. Montgomery

Many chapters were published as individual short stories in various magazines, and were adapted into this novel. In particular, we know of the following:

Magic for Marigold. Delineator, May 1926. Chapters 1&2.

Lost—A Child's Laughter. Delineator, June 1926. Chapter 7.

Bobbed Golidlocks. Delineator, July, 1926. Chapter 10.

Playmate. Delineator, August 1926. Chapter 21.

“IT”. Chatelaine, April 1929. Chapter 8.

One Clear Call. Household Magazine, August 1928. Chapter 15.

Too Few Cooks. Delineator, February 1925. Chapter 17 of Magic for Marigold, and Chapters 7-8 of Emily of New Moon.

To

Nora

Contents

1

What’s in a Name? 9

2

Sealed of the Tribe 31

3

April Promise 39

4

Marigold Goes A-visiting 66

5

The Door That Men Call Death 76

6

The Power of the Dog 101

7

Lost Laughter 114

8

“IT” 126

9

A Lesley Christmas 137

10

The Bobbing of Marigold 146

11

A Counsel of Perfection 164

12

Marigold Entertains 177

13

A Ghost is Laid 203

14

Bitterness of Soul 221

15

One Clear Call 234

16

One of Us 248

17

Not by Bread Alone 270

18

Red Ink Or—? 280

19

How It Came to Pass 293

20

The Punishment of Billy 308

21

Her Chrism of Womanhood 319

1What’s in a Name?

1

Once upon a time—which, when you come to think of it, is really the only proper way to begin a story—the only way that really smacks of romance and fairyland—all the Harmony members of the Lesley clan had assembled at Cloud of Spruce to celebrate Old Grandmother’s birthday as usual. Also to name Lorraine’s baby. It was a crying shame, as Aunt Nina pathetically said, that the little darling had been in the world four whole months without a name. But what could you do, with poor dear Leander dying in that terribly sudden way just two weeks before his daughter was born and poor Lorraine being so desperately ill for weeks and weeks afterwards? Not very strong yet, for that matter. And there was tuberculosis in her family, you know.

Aunt Nina was not really an aunt at all—at least, not of any Lesley. She was just a cousin. It was the custom of the Lesley caste to call every one “Uncle” or “Aunt” as soon as he or she had become too old to be fitly called by a first name among the young fry. There will be no end of these “aunts” and “uncles” bobbing in and out of this story—as well as several genuine ones. I shall not stop to explain which kind they were. It doesn’t matter. They were all Lesleys or married to Lesleys. That was all that mattered. You were born to the purple if you were a Lesley. Even the pedigrees of their cats were known.

All the Lesleys adored Lorraine’s baby. They had all agreed in loving Leander—about the only thing they had ever been known to agree on. And it was thirty years since there had been a baby at Cloud of Spruce. Old Grandmother had more than once said gloomily that the good old stock was running out. So this small lady’s advent would have been hailed with delirious delight if it hadn’t been for Leander’s death and Lorraine’s long illness. Now that Old Grandmother’s birthday had come, the Lesleys had an excuse for their long-deferred jollification. As for the name, no Lesley baby was ever named until every relative within get-at-able distance had had his or her say in the matter. The selection of a suitable name was, in their eyes, a much more important thing than the mere christening. And how much more in the case of a fatherless baby whose mother was a sweet soul enough—but—you know—a Winthrop!

Cloud of Spruce, the original Lesley homestead, where Old Grandmother and Young Grandmother and Mrs. Leander and the baby and Salome Silversides lived, was on the harbour shore, far enough out of Harmony village to be in the real country; a cream brick house—a nice chubby old house—so covered with vines that it looked more like a heap of ivy than a house; a house that had folded its hands and said, “I will rest.” Before it was the beautiful Harmony Harbour; with its purring waves, so close that in autumnal storms the spray dashed over the very doorsteps and encrusted the windows. Behind it was an orchard that climbed the slope. And about it always the soft sighing of the big spruce wood on the hill.

The birthday dinner was eaten in Old Grandmother’s room—which had been the “orchard room” until Old Grandmother, two years back, had cheerfully and calmly announced that she was tired of getting up before breakfast and working between meals.

“I’m going to spend the rest of my life being waited on,” she said. “I’ve had ninety years of slaving for other people—” and bossing them, the Lesleys said in their hearts. But not out loud, for it did really seem at times as if Old Grandmother’s ears could hear for miles. Uncle Ebenezer said something once about Old Grandmother, to himself, in his cellar at midnight, when he knew he was the only human being in the house. Next Sunday afternoon Old Grandmother cast it up to him. She said Lucifer had told her. Lucifer was her cat. And Uncle Ebenezer suddenly remembered that his cat had been sitting on the edge of the potato bin when he said that.

It was safest not to say things about Old Grandmother.

Old Grandmother’s room was a long, dim-green apartment running across the south end of the house, with a glass door opening right into the orchard. Its walls were hung with photographs of Lesley brides for sixty years back, most of them with enormous bouquets and wonderful veils and trains. Clementine’s photograph was among them—Clementine, Leander’s first wife, who had died six years ago with her little unnamed daughter. Old Grandmother had it hanging on the wall at the foot of her bed so that she could see it all the time. Old Grandmother had been very fond of Clementine. At least, she always gave Lorraine that impression.

The picture was good to look at—Clementine Lesley had been very beautiful. She was not dressed as a bride—in fact the picture had been taken just before her marriage and had a clan fame as “Clementine with the lily.” She was posed standing with her beautiful arms resting on a pedestal and in one slender, perfect hand—Clementine’s hands had become a tradition of loveliness—she held a lily, at which she was gazing earnestly. Old Grandmother had told Lorraine once that a distinguished guest at Cloud of Spruce, an artist of international fame, had exclaimed on seeing that picture,

“Exquisite hands! Hands into which a man might fearlessly put his soul!”

Lorraine had sighed and looked at her rather thin little hands. Not beautiful—scarcely even pretty; yet Leander had once kissed their finger-tips and said—but Lorraine did not tell Old Grandmother what Leander had said. Perhaps Old Grandmother might have liked her better if she had.

Old Grandmother had her clock in the corner by the bed—a clock that had struck for the funerals and weddings and goings and comings and meetings and partings of five generations; the grandfather clock her husband’s father had brought out from Scotland a hundred and forty years ago; the Lesleys plumed themselves on being Prince Edward Island pioneer stock. It was still keeping excellent time and Old Grandmother got out of bed every night to wind it. She would have done that if she had been dying.

Her other great treasure was in the opposite corner. A big glass case with Alicia, the famous Skinner doll, in it. Old Grandmother’s mother had been a Skinner and the doll had no part in Lesley traditions, but every Lesley child had been brought up in the fear and awe of it and knew its story. Old Grandmother’s mother’s sister had lost her only little daughter of three years and had never been “quite right” afterwards. She had had a waxen image of her baby made and kept it beside her always and talked to it as if it had been alive. It was dressed in a wonderful embroidered dress that had belonged to the dead baby, and wore one of her slippers. The other slipper was held in one waxen hand ready for the small bare foot that peeped out under the muslin flounces. The doll was so lifelike that Lorraine always shuddered when she passed it, and Salome Silversides was very doubtful of the propriety of having such a thing in the house at all, especially as she knew that Lazarre, the French hired man, thought and told that it was the Old Lady’s “Saint” and believed she prayed before it regularly. But all the Lesleys had a certain pride in it. No other Prince Edward Island family could boast a doll like that. It conferred a certain distinction upon them and tourists wrote it up in their local papers when they went back home.

Of course the cats were present at the festivity also. Lucifer and the Witch of Endor. Both of black velvet with great round eyes. Cloud of Spruce was noted for its breed of black cats with topaz-hued eyes. Its kittens were not scattered broadcast but given away with due discrimination.

Lucifer was Old Grandmother’s favourite. A remote, subtle cat. An inscrutable cat so full of mystery that it fairly oozed out of him. The Witch of Endor became her name but compared to Lucifer she was commonplace. Salome wondered secretly that Old Grandmother wasn’t afraid of a judgment for calling a cat after the Old Harry. Salome “liked cats in their place” but she was furious when Uncle Klon said to her once,

“Salome Silversides! Why, you ought to be a cat yourself with a name like that. A sleek, purring plushy Maltese.”

“I’m sure I don’t look like a cat,” said Salome, highly insulted. And Uncle Klon agreed that she did not.

Old Grandmother was a gnomish dame of ninety-two who meant to live to be a hundred. A tiny, shrunken, wrinkled thing with flashing black eyes. There was a Puckish hint of malice in most things she said or did. She ruled the whole Lesley clan and knew everything that was said and done in it. If she had given up “slaving” she certainly had not given up “bossing.” To-day she was propped up on crimson cushions with a fresh, frilled, white cap tied around her face, eating her dinner heartily and thinking things not lawful to be uttered about her daughters-in-law and her granddaughters-in-law and her great-granddaughters-in-law.

2

Young Grandmother, a mere lass of sixty-five, sat at the head of the long table—a tall, handsome lady with bright, steel-blue eyes and white hair, whom Old Grandmother thought a somewhat pert young thing. There was nothing of the traditional grandmother of caps and knitting about her. She was like a stately old princess in her purple velvet gown with its wonderful lace collar. The gown had been made eight years before, but when Young Grandmother wore anything it seemed at once in the height of the fashion. Most of the Lesleys present thought she should not have laid aside her black even for a birthday dinner. But Young Grandmother did not care what they thought any more than Old Grandmother did. She had been a Blaisdell—one of the “the stubborn Blaisdells”—and the Blaisdell traditions were as good as the Lesley traditions any day.

Lorraine sat on the right of Young Grandmother at the table, with the baby in her cradle beside her. Because of the baby she had a certain undeniable importance never before conceded her. All the Lesleys had been more or less opposed to Leander’s “second choice.” Only the fact that she was a minister’s daughter appeased them. She was a shy, timid, pretty creature—quite insignificant except for her enormous masses of lustrous, pale gold hair. Her small face was sweet and flower-like and she had peculiarly soft grey-blue eyes with long lashes. She looked very young and fragile in her black dress. But she was beginning to be a little happy once more. Her arms, that had reached out so emptily in the silence of the night, were filled again. The fields and hills around Cloud of Spruce that had been so stark and bare and chill when her little lady came were green and golden now, spilled over with blossoms, and the orchard was an exquisite perfumed world by itself. One could not be altogether unhappy, in springtime, with such a wonderful, unbelievable baby.

The baby lay in the old Heppelwhite cradle where her father and grandfather had lain before her—a quite adorable baby, with a saucy little chin, tiny hands as exquisite as the apple-blossoms, eyes of fairy blue, and the arrogant, superior smile of babies before they have forgotten all the marvellous things they know at first. Lorraine could hardly eat her dinner for gazing at her baby—and wondering. Would this tiny thing ever be a dancing, starry-eyed girl—a white bride—a mother? Lorraine shivered. It did not do to look so far ahead. Aunt Anne got up, brought a shawl, and tenderly put it around Lorraine’s shoulders. Lorraine was almost melted, for the June day was hot, but she wore the shawl all through dinner rather than hurt Aunt Anne’s feelings. That one fact described Lorraine.

On Young Grandmother’s left sat Uncle Klondike, the one handsome, mysterious, unaccountable member of the Lesley clan, with his straight, heavy eyebrows, his flashing blue eyes, his mane of tawny hair and the red-gold beard which had caused a sentimental Harmony lady of uncertain years to say that he made her think of those splendid old Vikings.

Uncle Klondike’s real name was Horace, but ever since he had come back from the Yukon with gold dropping out of his pockets he had been known as Klondike Lesley. His deity was the God of All Wanderers and in his service Horace Lesley had spent wild, splendid, adventurous years.

When Klondike had been a boy at school he had a habit of looking at certain places on the map and saying, “I’ll go there.” Go he did. He had stood on the southernmost boulder of Ceylon and sat on Buddhist cairns at the edge of Thibet. The Southern Cross was a pal and he had heard the songs of nightingales in the gardens of the Alhambra. India and the China seas were to him as a tale that is told, and he had walked alone in great Arctic spaces under northern lights. He had lived in many places but he had never thought of any of them as home. That name had all unconsciously been kept sacred to the long, green seaward-looking glen where he had been born.

And finally he had come home, sated, to live the rest of his life a decent law-abiding clansman, whereof the conclusive sign and token was that he had trimmed his moustache and beard into decency. The moustache had been particularly atrocious. Its ends hung down nearly as far as his beard did. When Aunt Anne asked him despairingly why upon earth he wore a moustache like that he retorted that he wrapped it round his ears to keep them warm. The clan were horribly afraid he meant to go on wearing them—for Uncle Klon was both Lesley and Blaisdell. He finally had them clipped, though he could never be induced to go the length of a clean-shaven face, fashion or no fashion. But, though he went to bed early at least once a week, he still savoured life with gusto and the clan were always secretly much afraid of him and his satiric winks and cynical speeches. Aunt Nina, in particular, had held him in terror ever since the day she had told him proudly that her husband had never lied to her.

“Oh, you poor woman,” said Uncle Klon, with real sympathy in his tone.

Nina supposed there was a joke somewhere but she could never find it. She was a W. C. T. U. and an I. O. D. E. and most of the other letters of the alphabet—but somehow she found it hard to get the hang of Klondike’s jokes.

Klondike Lesley was known to be a woman-hater. He scoffed openly at all love, more especially the supreme absurdity of love at first sight. This did not prevent his clan from trying for years to marry him off. It would be the making of Klondike if he had a good wife who would stand no nonsense. They were very obvious about it, and with the renowned Lesley frankness, recommended several excellent brides to him. But Klondike Lesley was notoriously hard to please.

“Katherine Nichols?”

“But look at the thick ankles of her.”

“Emma Goodfellow?”

“Her mother used to call out ‘meow’ in church whenever the minister said something she didn’t like. Can’t risk heredity.”

“Rose Osborn?”

“I can’t stand a woman with pudgy hands.”

“Sara Jennet?”

“An egg without salt.”

“Lottie Parks?”

“I’d like her as a flavouring, not as a dish.”

“Ruth Russell?”—triumphantly, as having at last hit on a woman with whom no reasonable man could find fault.

“Too peculiar. When she has nothing to say she doesn’t talk. That’s really too uncanny in a woman, you know.”

“Dorothy Porter?”

“Ornamental by candlelight. But I don’t believe she’d look so well at breakfast.”

“Amy Ray?”

“Always purring, blinking, sidling, clawing. Nice small pussy-cat but I’m no mouse.”

“Agnes Barr?”

“A woman who says Coué’s formula instead of her prayers!”

“Olive Purdy?”

“Tongue—temper—and tears. Go sparingly, thank you.”

Even Old Grandmother took a hand and met with no better success. She was wiser than to throw any one girl at his head—the men of the Lesley clan never had married the women picked out for them. But she had her own way of managing things.

“ ‘He travels the fastest who travels alone,’ ” was all she could get out of Klondike.

“Very clever of you,” said Old Grandmother, “if travelling fast is all there is to life.”

“Not clever of me. Don’t you know your Kipling, Grandmother?”

“What is a Kipling?” said Old Grandmother.

Uncle Klondike did not tell her. He merely said he was doomed to die a bachelor—and could not escape his kismet.

Old Grandmother was not a stupid woman even if she didn’t know what a Kipling was.

“You’ve waited too long-you’ve lost your appetite,” she said shrewdly.

The Lesleys gave it up. No use trying to fit this exasperating relative with a wife. A bachelor Klon remained, with an awful habit of wiring “sincere sympathy” when any of his friends got married. Perhaps it was just as well. His nephews and nieces might benefit, especially Lorraine’s baby whom he evidently worshipped. So here he was, unwedded, light-hearted and content, watching them all with his amused smile.

Lucifer had leaped on his knee as soon as he had sat down. Lucifer condescended to very few but, as he told the Witch of Endor, Klondike Lesley had a way with him. Uncle Klon fed Lucifer with bits from his own plate and Salome, who ate with the family because she was a fourth cousin of Jane Lyle, who had married the stepbrother of a Lesley, thought it ghastly.

3

The baby had to be talked all over again and Uncle William-over-the-bay covered himself with indelible disgrace by saying dubiously,

“She is not—ahem—really a pretty child, do you think?”

“All the better for her future looks,” said Old Grandmother tartly. She had been biding her moment, like a watchful cat, to give a timely dig. “You,” she added maliciously, “were a very pretty baby—though you did not have any more hair on your head than you have now.”

“Beauty is a fatal gift. She will be better without it,” sighed Aunt Nina.

“Then why do you cold-cream your face every night and eat raw carrots for your complexion and dye your hair?” asked Old Grandmother.

Aunt Nina couldn’t imagine how Old Grandmother knew about the carrots. She had no cat to tattle to Lucifer.

“We are all as God made us,” said Uncle Ebenezer piously.

“Then God botched some of us,” snapped Old Grandmother, looking significantly at Uncle Ebenezer’s enormous ears and the frill of white whisker around his throat that made him look oddly like a sheep. But then, reflected Old Grandmother, whoever might be responsible for the nose, it was hardly fair to blame God for Ebenezer’s whiskers.

“She has a peculiarly shaped hand, hasn’t she?” persisted Uncle William-over-the-bay.

Aunt Anne bent over and kissed one of the little hands.

“The hand of an artist,” she said.

Lorraine looked at her gratefully and hated Uncle William-over-the-bay bitterly for ten minutes under her golden hair.

“Handsome is as handsome does,” said Uncle Archibald, who rarely opened his mouth save to emit a proverb.

“Would you mind telling me, Archibald,” said Old Grandmother pleasantly, “if you really look that solemn when you’re asleep.”

No one answered her. Aunt Mary Martha-over-the-bay, the only one who could have answered, had been dead for ten years.

“Whether she’s pretty or not, she’s going to have very long lashes,” said Aunt Anne, reverting to the baby as a safer subject of conversation. There was no sense in letting Old Grandmother start a family row for her own amusement so soon after poor Leander’s passing away.

“God help the men then,” said Uncle Klon gravely.

Aunt Anne wondered why Old Grandmother was laughing to herself until the bed shook. Aunt Anne reflected that it would have been just as well if Klondike with his untimely sense of humour had not been present in a serious assemblage like this.

“Well, we must give her a pretty name, anyhow,” said Aunt Flora briskly. “It’s simply a shame that it’s been left as long as this. No Lesley ever was before. Come, Grandmother, you ought to name her. What do you suggest?”

Old Grandmother affected the indifferent. She had three namesakes already so she knew Leander’s baby wouldn’t be named after her.

“Call it what you like,” she said. “I’m too old to bother about it. Fight it out among yourselves.”

“But we’d like your advice, Grandmother,” unfortunately said Aunt Leah, whom Old Grandmother was just detesting because she had noticed the minute Leah shook hands with her that she had had her nails manicured.

“I have no advice to give. I have nothing but a little wisdom and I cannot give you that. Neither can I help it if a woman has a bargain-counter nose.”

“Are you referring to my nose,” inquired Aunt Leah with spirit. She often said she was the only one in the clan who wasn’t afraid of Old Grandmother.

“The pig that’s bit squeals,” retorted Old Grandmother. She leaned back on her pillows disdainfully and sipped her tea with a vengeance. She had got square with Leah for manicuring her nails.

She had insisted on having her dinner first so that she might watch the others eating theirs. She knew it made them all more or less uncomfortable. Oh, but it was fine to be able to be disagreeable again. She had had to be so good and considerate for four months. Four months was long enough to mourn for anybody. Four months of not daring to give anybody a wigging. They had seemed like four centuries.

Lorraine sighed. She knew what she wanted to call her baby. But she knew that she would never have the courage to say it. And if she did she knew they would never consent to it. When you married into a family like the Lesleys you had to take the consequences. It was very hard when you couldn’t name your own baby—when you were not even asked what you’d like it named. If Lee had only lived it would have been different. Lee, who was not a bit like the other Lesleys—except Uncle Klon, a little—Lee, who loved wonder and beauty and laughter—laughter that had been hushed so suddenly. Surely the jests of Heaven must have had more spice since he had joined in them. How he would have howled at this august conclave over the naming of his baby! How he would have brushed them aside! Lorraine felt sure he would have let her call her baby—

“I think,” said Mrs. David Lesley, throwing her bombshell gravely and sadly, “that it would only be graceful and fitting that she should be called after Leander’s first wife.”

Mrs. David and Clementine had been very intimate friends. But Clementine! Lorraine shivered again and wished she hadn’t, for Aunt Anne’s eye looked like another shawl.

Everybody looked at Clementine’s picture.

“Poor little Clementine,” sighed Aunt Stasia in a tone that made Lorraine feel she should never have taken poor little Clementine’s place.

“Do you remember what lovely jet black hair she had?” asked Aunt Marcia.

“And what lovely hands?” said Great-Aunt Matilda.

“She was so young to die,” sighed Aunt Josephine.

“She was such a sweet girl,” said Great-Aunt Elizabeth.

“A sweet girl all right,” agreed Uncle Klon, “but why condemn an innocent child to carry a name like that all her life? That would really be a thin.”

The clan, with the exception of Mrs. David, felt grateful to him and looked it, especially Young Grandmother. The name simply wouldn’t have done, no matter how sweet Clementine was. That horrid old song, for instance—Oh, my darling Clementine, that boys used to howl along the road at nights. No, no, not for a Lesley. But Mrs. David was furious. Not only because Klondike disagreed with her but because he was imitating her old lisp, so long outgrown that it really was mean of him to drag it up again like this.

“Will you have some more dressing?” inquired Young Grandmother graciously.

“No, thank you.” Mrs. David was not going to have any more, by way of signifying displeasure. Later on she took a still more terrible revenge by leaving two-thirds of her pudding uneaten, knowing that Young Grandmother had concocted it. Young Grandmother woke up in the night and wondered if anything could really have been the matter with the pudding. The others might have eaten it out of politeness.

“If Leander’s name had been almost anything else she might have been named for her father,” said Great-Uncle Walter. “Roberta—Georgina—Johanna—Andrea—Stephanie—Wilhelmina—”

“Or Davidena,” said Uncle Klon. But Great-Uncle Walter ignored him.

“You can’t make anything out of a name like Leander. Whatever did you call him that for, Marian?”

“His grandfather named him after him who swam the Hellespont,” said Young Grandmother as rebukingly as if she had not, thirty-five years before, cried all one night because Old Grandfather had given her baby such a horrid name.

“She might be called Hero,” said Uncle Klon.

“We had a dog called that once,” said Old Grandmother.

“Leander didn’t tell you before he died that he wanted any special name, did he, Lorraine?” inquired Aunt Nina.

“No,” faltered Lorraine. “He—he had so little time to tell me—anything.”

The clan frowned at Nina as a unit. They thought she was very tactless. But what could you expect of a woman who wrote poetry and peddled it about the country? Writing it might have been condoned—and concealed. After all, the Lesleys were not intolerant and everybody had some shortcomings. But selling it openly!

“I should like baby to be called Gabriella,” persisted Nina.

“There has never been such a name among the Lesleys,” said Old Grandmother. And that was that.

“I think it’s time we had some new names,” said the poetess rebelliously. But every one looked stony, and Nina began to cry. She cried upon the slightest provocation. Lorraine remembered that Leander had always called her Mrs. Gummidge.

“Come, come,” said Old Grandmother, “surely we can name this baby as well comfortably as uncomfortably. Don’t make the mistake, Nina, of thinking that you are helping things along by making a martyr of yourself.”

“What do you think, Miss Silversides?” inquired Uncle Charlie, who thought Salome was being entirely ignored and didn’t like it.

“Oh, it doesn’t matter what I think. I am of no consequence,” said Salome, ostentatiously helping herself to the pickles.

“Come, come, now, you’re one of the family,” coaxed Uncle Charlie, who knew—so he said—how to handle women.

“Well”—Salome relaxed because she was really dying to have her say in it—“I’ve always thought names that ended in ‘ine’ were so elegant. My choice would be Rosaline.”

“Or Evangeline,” said Great-Uncle Walter.

“Or Eglantine,” said Aunt Marcia eagerly.

“Or Gelatine,” said Uncle Klon.

There was a pause.

“Juno would be such a nice name,” said Cousin Teresa.

“But we are Presbyterians,” said Old Grandmother.

“Or Robinette,” suggested Uncle Charlie.

“We are English,” said Young Grandmother.

“I think Yvonne is such a romantic name,” said Aunt Flora.

“Names have really nothing to do with romance,” said Uncle Klon. “The most thrilling and tragic love affair I ever knew was between a man named Silas Twingletoe and a woman named Kezia Birtwhistle. It’s my opinion children shouldn’t be named at all. They should be numbered until they’re grown up, then choose their own names.”

“But then you are not a mother, my dear Horace,” said Young Grandmother tolerantly.

“Besides, there’s an Yvonne Clubine keeping a lingerie shop in Charlottetown,” said Aunt Josephine.

“Lingerie? If you mean underclothes for heaven’s sake say so,” snapped Old Grandmother.

“Juanita is a rather nice uncommon name,” suggested John Eddy Lesley-over-the-bay. “J-u-a-n-i-t-a.”

“Nobody would know how to spell it or pronounce it,” said Aunt Marcia.

“I think,” began Uncle Klon—but Aunt Josephine took the road.

“I think—”

“Place aux dames,” murmured Uncle Klon. Aunt Josephine thought he was swearing but ignored him.

“I think the baby should be called after one of our missionaries. It’s a shame that we have three foreign missionaries in the connection and not one of them has a namesake—even if they are only fourth cousins. I suggest we call her Harriet after the oldest one.”

“But,” said Aunt Anne, “that would be slighting Ellen and Louise.”

“Well,” said Young Grandmother haughtily—Young Grandmother was haughty because nobody had suggested naming the baby after her—“call her the whole three names, Harriet Ellen Louise Lesley. Then no fourth cousin need feel slighted.”

The suggestion seemed to find favour. Lorraine caught her breath anxiously and looked at Uncle Klon. But rescue came from another quarter.

“Have you ever,” said Old Grandmother with a wicked chuckle, “thought what the initials spell?”

They hadn’t. They did. Nothing more was said about missionaries.

4

“Sylvia is a beautiful name,” ventured Uncle Howard, whose first sweetheart had been a Sylvia.

“You couldn’t call her that,” said Aunt Millicent in a shocked tone. “Don’t you remember Great-Uncle Marshall’s Sylvia went insane? She died filling the air with shrieks. I think Bertha would be more suitable.”

“Why, there’s a Bertha in John C. Lesley’s family-over-the-bay,” said Young Grandmother.

John C. was a distant relative who was “at outs” with his clan. So Bertha would never do.

“Wouldn’t it be nice to name her Adela?” said Aunt Anne. “You know Adela is the only really distinguished person the connection has ever produced. A famous authoress—”

“I should like the mystery of her husband’s death to be cleared up before any grandchild of mine is called after her,” said Young Grandmother austerely.

“Nonsense, Mother! You surely don’t suspect Adela.”

“There was arsenic in the porridge,” said Young Grandmother darkly.

“I’ll tell you what the child should be called,” said Aunt Sybilla, who had been waiting for the psychic moment. “Theodora! It was revealed to me in a vision of the night. I was awakened by a feeling of icy coldness on my face. I came all out in goose flesh. And I heard a voice distinctly pronounce the name—Theodora. I wrote it down in my diary as soon as I arose.”

John Eddy Lesley-over-the-bay laughed. Sybilla hated him for weeks for it.

“I wish,” said sweet old Great-Aunt Matilda, “that she could be called after my little girl who died.”

Aunt Matilda’s voice trembled. Her little girl had been dead for fifty years but she was still unforgotten. Lorraine loved Aunt Matilda. She wanted to please her. But she couldn’t—she couldn’t—call her dear baby Emmalinza.

“It’s unlucky to call a child after a dead person,” said Aunt Anne positively.

“Why not call the baby Jane,” said Uncle Peter briskly. “My mother’s name—a good, plain, sensible name that’ll wear. Nickname it to suit any age. Jenny—Janie—Janet—Jeannette—Jean—and Jane for the seventies.”

“Oh, wait till I’m dead—please,” wailed Old Grandmother. “It would always make me think of Jane Putkammer.”

Nobody knew who Jane Putkammer was or why Old Grandmother didn’t want to think of her. As nobody asked why—the dessert having just been begun—Old Grandmother told them.

“When my husband died she sent me a letter of condolence written in red ink. Jane, indeed!”

So the baby escaped being Jane. Lorraine felt really grateful to Old Grandmother. She had been afraid Jane might carry the day. And how fortunate there was such a thing as red ink in the world.

“Funny about nicknames,” said Uncle Klon. “I wonder did they have nicknames in Biblical times. Was Jonathan ever shortened into Jo? Was King David ever called Dave? And fancy Melchizedek’s mother always calling him that.”

“Melchizedek hadn’t a mother,” said Mrs. David triumphantly—and forgave Uncle Klon. But not Young Grandmother. The pudding remained uneaten.

“Twenty years ago Jonathan Lesley gave me a book on ‘The Hereafter,’ ” said Old Grandmother reminiscently. “And he’s been in the Hereafter eighteen years and I am still in the Here.”

“Any one would think you expected to live forever,” said Uncle Jarvis, speaking for the first time. He had been sitting in silence, hoping gloomily that Leander’s baby was an elect infant. What mattered a name compared to that?

“I do,” said Old Grandmother, chuckling. That was one for Jarvis, the solemn old ass.

“We’re not really getting anywhere about the baby’s name, you know,” said Uncle Paul desperately.

“Why not let Lorraine name her own baby?” said Uncle Klon suddenly. “Have you any name you’d like her called, dear?”

Again Lorraine caught her breath. Oh, hadn’t she! She wanted to call her baby Marigold. In her girlhood she had had a dear friend named Marigold. The only girl-friend she ever had. Such a dear, wonderful, bewitching, lovable creature. She had filled Lorraine’s starved childhood with beauty and mystery and affection. And she had died. If only she might call her baby Marigold! But she knew the horror of the clan over such a silly, fanciful, outlandish name. Old Grandmother—Young Grandmother—no, they would never consent. She knew it. All her courage exhaled from her in a sigh of surrender.

“No-o-o,” she said in a small, hopeless voice. Oh, if she were only not such a miserable coward.

And that terrible Old Grandmother knew it.

“She’s fibbing,” she thought. “She has a name but she’s too scared to tell it. Clementine, now—she would have stood on her own feet and told them what was what.”

Old Grandmother looked at Clementine, forever gazing at her lily, and forgot that the said Clementine’s ability to stand on her own feet and tell people—even Old Grandmother—what was what had not especially commended her to Old Grandmother at one time. But Old Grandmother liked people with a mind of their own—when they were dead.

Old Grandmother was beginning to feel bored with the whole matter. What a fuss over a name. As if it really mattered what that mite in the cradle, with the golden fuzz on her head, was called. Old Grandmother looked at the tiny sleeping face curiously. Lorraine’s hair but Leander’s chin and brow and nose. A fatherless baby with only that foolish Winthrop girl for a mother.

“I must live long enough for her to remember me,” thought Old Grandmother. “It’s only a question of keeping on at it. Marian has no imagination and Lorraine has too much. Somebody must give that child a few hints to live by, whether she’s to be minx or madonna.”

“If it was only a boy it would be so easy to name it,” said Uncle Paul.

Then for ten minutes they wrangled over what they would have called it if it had been a boy. They were beginning to get quite warm over it when Aunt Myra took a throbbing in the back of her neck.

“I’m afraid one of my terrible headaches is coming on,” she said faintly.

“What would women do if headaches had never been invented?” asked Old Grandmother. “It’s the most convenient disease in the world. It can come on so suddenly—go so conveniently. And nobody can prove we haven’t got it.”

“I’m sure no one has ever suffered as I do,” sighed Myra.

“We all think that,” said Old Grandmother, seeing a chance to shoot another poisoned arrow. “I’ll tell you what’s the matter with you. Eye strain. You should really wear glasses at your age, Myra.”

“Why can’t those headaches be cured?” said Uncle Paul. “Why don’t you try a new doctor?”

“Who is there to try now that poor Leander is in his grave?” wailed Myra. “I don’t know what we Lesleys are ever going to do without him. We’ll just have to die. Dr. Moorhouse drinks and Dr. Stackley is an evolutionist. And you wouldn’t have me go to that woman-doctor, would you?”

No, of course not. No Lesley would go to that woman-doctor. Dr. M. Woodruff Richards had been practising in Harmony for two years, but no Lesley would have called in a woman-doctor if he had been dying. One might as well commit suicide. Besides, a woman-doctor was an outrageous portent, not to be tolerated or recognised at all. As Great-Uncle Robert said indignantly, “The weemen are gittin’ entirely too intelligent.”

Klondike Lesley was especially sarcastic about her. “An unsexed creature,” he called her. Klondike had no use for unfeminine women who aped men. “Neither fish nor flesh nor good red herring,” as Young Grandfather had been wont to say. But they talked of her through their coffee and did not again revert to the subject of the baby’s name. They were all feeling a trifle sore over that. It seemed to them all that neither Old Grandmother nor Young Grandmother nor Lorraine had backed them up properly. With the result that all the guests went home with the great question yet unsettled.

“Just as I expected. All squawks—nothing but squawks as usual,” said Old Grandmother.

“We might have known what would happen when we had this on Friday,” said Salome, as she washed up the dishes.

“Well, the great affair is over,” said Lucifer to the Witch of Endor as they discussed a plate of chicken bones and Pope’s noses on the back veranda, “and that baby hasn’t got a name yet. But these celebrations are red-letter days for us. Listen to me purr.”

2Sealed of the Tribe

1

Things were rather edgy in the Lesley clan for a few weeks. As Uncle Charlie said, they had their tails up. Cousin Sybilla was reported to have gone on a hunger strike—which she called a fast—about it. Stasia and Teresa, two affectionate sisters, quarrelled over it and wouldn’t speak to each other. There was a connubial rupture between Uncle Thomas and Aunt Katherine because she wanted to consult ouija about a name. Obadiah Lesley, who in thirty years had never spoken a cross word to his wife, rated her so bitterly for wanting to call the baby Consuela that she went home to her mother for three days. An engagement trembled in the balance. Myra’s throbbings in the neck became more frequent than ever. Uncle William-over-the-bay vowed he wouldn’t play checkers until the child was named. Aunt Josephine was known to be praying about it at a particular hour every day. Nina cried almost ceaselessly over it and gave up peddling poetry for the time being, which led Uncle Paul to remark that it was an ill wind which blew no good. Young Grandmother preserved an offended silence. Old Grandmother laughed to herself until the bed shook. Salome and the cats held their peace, though Lucifer carefully kept his tail at half-mast. Everybody was more or less cool to Lorraine because she had not taken his or her choice. It really looked as if Leander’s baby was never going to get a name.

Then—the shadow fell. One day the little lady of Cloud of Spruce seemed fretful and feverish. The next day more so. The third day Dr. Moorhouse was called—the first time for years that a Lesley had to call in an outside doctor. For three generations there had been a Dr. Lesley at Cloud of Spruce. Now that Leander was gone they were all at sea. Dr. Moorhouse was brisk and cheerful. Pooh-pooh! No need to worry—not the slightest. The child would be all right in a day or two.

She wasn’t. At the end of a week the Lesley clan were thoroughly alarmed. Dr. Moorhouse had ceased to pooh-pooh. He came anxiously twice a day. And day by day the shadow deepened. The baby was wasting away to skin and bone. Anguished Lorraine hung over the cradle with eyes that nobody could bear to look at. Everybody proposed a different remedy but nobody was offended if it wasn’t used. Things were too serious for that. Only Nina was almost sent to Coventry because she asked Lorraine one day if infantile paralysis began like that, and Aunt Marcia was frozen out because she heard a dog howling one night. Also, when Flora said she had found a diamond-shaped crease in a clean tablecloth—a sure sign of death in the year—Klondike insulted her. But Klondike was forgiven because he was nearly beside himself over the baby’s condition.

Dr. Moorhouse called in Dr. Stackley, who might be an evolutionist but had a reputation of being good with children. After a long consultation they changed the treatment; but there was no change in the little patient. Klondike brought a specialist from Charlottetown who looked wise and rubbed his hands and said Dr. Moorhouse was doing all that could be done and that while there was life there was always hope, especially in the case of children.

“Whose vitality is sometimes quite extraordinary,” he said gravely, as if enunciating some profound discovery of his own.

It was at this juncture that Great-Uncle Walter, who hadn’t gone to church for thirty years, made a bargain with God that he would go if the child’s life was spared, and that Great-Uncle William-over-the-bay recklessly began playing checkers again. Better break a vow before a death than after it. Teresa and Stasia had made up as soon as the baby took ill, but it was only now that the coolness between Thomas and Katherine totally vanished. Thomas told her for goodness’ sake to try ouija or any darned thing that might help. Even Old Cousin James T., who was a black sheep and never called “Uncle” even by the most tolerant, came to Salome one evening.

“Do you believe in prayer?” he asked fiercely.

“Of course I do,” said Salome indignantly.

“Then pray. I don’t—so it’s no use for me to pray. But you pray your darnedest.”

2

A terrible day came when Dr. Moorhouse told Lorraine gently that he could do nothing more. After he had gone Young Grandmother looked at Old Grandmother.

“I suppose,” she said in a low voice, “we had better take the cradle into the spare room.”

Lorraine gave a bitter cry. This was equivalent to a death sentence. At Cloud of Spruce, just as with the Murrays down at Blair Water, it was a tradition that dying people must be taken into the spare room.

“You’ll do one thing before you take her into the spare room,” said Old Grandmother fiercely. “Moorhouse and Stackley have given up the case. They’ve only half a brain between them anyhow. Send for that woman-doctor.”

Young Grandmother looked thunderstruck. She turned to Uncle Klon, who was sitting by the baby’s cradle, his haggard face buried in his hands.

“Do you suppose—I’ve heard she was very clever—they say she was offered a splendid post in a children’s hospital in Montreal but preferred general practice—”

“Oh, get her, get her,” said Klondike—savage from the bitter business of hoping against hope. “Any port in a storm. She can’t do any harm now.”

“Will you go for her, Horace,” said Young Grandmother quite humbly.

Klondike Lesley uncoiled himself and went. He had never seen Dr. Richards before—save at a distance, or spinning past him in her smart little runabout. She was in her office and came forward to meet him gravely sweet.

She had a little, square, wide-lipped, straight-browed face like a boy’s. Not pretty but haunting. Wavy brown hair with one teasing, unruly little curl that would fall down on her forehead, giving her a youthful look in spite of her thirty-five years. What a dear face! So wide at the cheek-bones—so deep grey-eyed. With such a lovely, smiling, generous mouth. Some old text of Sunday-school days suddenly flitted through Klondike Lesley’s dazed brain:

“She will do him good and not evil all the days of her life.”

For just a second their eyes met and locked. Only a second. But it did the work of years. The irresistible woman had met the immovable man and the inevitable had happened. She might have had thick ankles—only she hadn’t; her mother might have meowed all over the church. Nothing would have mattered to Klondike Lesley. She made him think of all sorts of lovely things, such as sympathy, kindness, generosity, and women who were not afraid to grow old. He had the most extraordinary feeling that he would like to lay his head on her breast and cry, like a little boy who had got hurt, and have her stroke his head and say,

“Never mind—be brave—you’ll soon feel better, dear.”

“Will you come to see my little niece?” he heard himself pleading. “Dr. Moorhouse has given her up. We are all very fond of her. Her mother will die if she cannot be saved. Won’t you come?”

“Of course I will,” said Dr. Richards.

She came. She said little, but she did some drastic things about diet and sleeping. Old and Young Grandmothers gasped when she ordered the child’s cradle moved out on the veranda. Every day for two weeks her light, steady footsteps came and went about Cloud of Spruce. Lorraine and Salome and Young Grandmother hung breathlessly on her briefest word.

Old Grandmother saw her once. She had told Salome to bring “the woman-doctor in,” and they had looked at each other for a few minutes in silence. The steady, sweet, grey eyes had gazed unquailingly into the piercing black ones.

“If a son of mine had met you I would have ordered him to marry you,” Old Grandmother said at last with a chuckle.

The little humorous quirk in Dr. Richards’ mouth widened to a smile. She looked around her at all the laughing brides of long ago in their billows of tulle.

“But I would not have married him unless I wanted to,” she said.

Old Grandmother chuckled again.

“Trust you for that.” But she never called her “the woman-doctor” again. She spoke with her own dignity of “Dr. Richards”—for a short time.

Klondike brought Dr. Richards to Cloud of Spruce and took her away. Her own car was laid up for repairs. But nobody was paying much attention to Klondike just then.

At the end of the two weeks it seemed to Lorraine that the shadow had ceased to deepen on the little wasted face.

A few more days—was it not lightening—lifting? At the end of three more weeks Dr. Richards told them that the baby was out of danger. Lorraine fainted and Young Grandmother shook and Klondike broke down and cried unashamedly like a schoolboy.

3

A few days later the clan had another conclave—a smaller and informal one. The aunts and uncles present were all genuine ones. And it was not, as Salome thankfully reflected, on a Friday.

“This child must be named at once,” said Young Grandmother authoritatively. “Do you realize that she might have died without a name?”

The horror of this kept the Lesleys silent for a few minutes. Besides, every one dreaded starting up another argument so soon after those dreadful weeks. Who knew but what it had been a judgment on them for quarrelling over it?

“But what shall we call her?” said Aunt Anne timidly.

“There is only one name you can give her,” said Old Grandmother, “and it would be the blackest ingratitude if you didn’t. Call her after the woman who has saved her life, of course.”

The Lesleys looked at each other. A simple, graceful, natural solution of the problem—if only—

“But Woodruff!” sighed Aunt Marcia.

“She’s got another name, hasn’t she?” snapped Old Grandmother. “Ask Horace there what M stands for? He can tell you, or I’m much mistaken.”

Every one looked at Klondike. In the anxiety of the past weeks everybody in the clan had been blind to Klondike’s goings-on—except perhaps Old Grandmother.

Klondike straightened his shoulders and tossed back his mane. It was as good a time as any to tell something that would soon have to be told.

“Her full name,” he said, “is now Marigold Woodruff Richards, but in a few weeks’ time it will be Marigold Woodruff Lesley.”

“And that,” remarked Lucifer to the Witch of Endor under the milk bench at sunset, with the air of a cat making up his mind to the inevitable, “is that.”

“What do you think of her?” asked the Witch, a little superciliously.

“Oh, she has points,” conceded Lucifer. “Kissable enough.”

The Witch of Endor, being wise in her generation, licked her black paws and said no more, but continued to have her own opinion.

3April Promise

1

On the evening of Old Grandmother’s ninety-eighth birthday there was a sound of laughter on the dark staircase—which meant that Marigold Lesley, who had lived six years and thought the world a very charming place, was dancing downstairs. You generally heard Marigold before you saw her. She seldom walked. A creature of joy, she ran or danced. “The child of the singing heart,” Aunt Marigold called her. Her laughter always seemed to go before her. Both Young Grandmother and Mother, to say nothing of Salome and Lazarre, thought that golden trill of laughter echoing through the somewhat prim and stately rooms of Cloud of Spruce the loveliest sound in the world. Mother often said this. Young Grandmother never said it. That was the difference between Young Grandmother and Mother.

Marigold squatted down on the broad, shallow, uneven sandstone steps at the front door and proceeded to think things over—or, as Aunt Marigold, who was a very dear, delightful woman, phrased it, “make magic for herself.” Marigold was always making magic of some kind.

Already, even at six, Marigold found this an entrancing occupation—“int’resting,” to use her own pet word. She had picked it up from Aunt Marigold and from then to the end of life things would be for Marigold interesting or uninteresting. Some people might demand of life that it be happy or untroubled or successful. Marigold Lesley would only ask that it be interesting. Already she was looking with avid eyes on all the exits and entrances of the drama of life.

There had been a birthday party for Old Grandmother that day, and Marigold had enjoyed it—especially that part in the pantry about which nobody save she and Salome knew. Young Grandmother would have died of horror if she had known how many of the whipped cream tarts Marigold had actually eaten.

But she was glad to be alone now and think things over. In Young Grandmother’s opinion Marigold did entirely too much thinking for so small a creature. Even Mother, who generally understood, sometimes thought so too. It couldn’t be good for a child to have its mind prowling in all sorts of corners. But everybody was too tired after the party to bother Marigold and her thoughts just now, so she was free to indulge in a long delightful reverie. Marigold was, she would have solemnly told you, “thinking over the past.” Surely a most fitting thing to do on a birthday, even if it wasn’t your own. Whether all her thoughts would have pleased Young Grandmother, or even Mother, if they had known them, there is no saying. But then they did not know them. Long, long ago—when she was only five and a half—Marigold had horrified her family—at least the Grandmotherly part of it—by saying in her nightly prayer, “Thank you, dear God, for ’ranging it so that nobody knows what I think.” Since then Marigold had learned worldly wisdom and did not say things like that out loud—in her prayers. But she continued to think privately that God was very wise and good in making thoughts exclusively your own. Marigold hated to have people barging in, as Uncle Klon would have said, on her little soul.

But then, as Young Grandmother would have said and did say, Marigold always had ways no orthodox Lesley baby ever thought of having—“the Winthrop coming out in her,” Young Grandmother muttered to herself. All that was good in Marigold was Lesley and Blaisdell. All that was bad or puzzling was Winthrop. For instance, that habit of hers of staring into space with a look of rapture. What did she see? And what right had she to see it? And when you asked her what she was thinking of she stared at you and said, “Nothing.” Or else propounded some weird, unanswerable problem such as, “Where was I before I was me?”