9,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

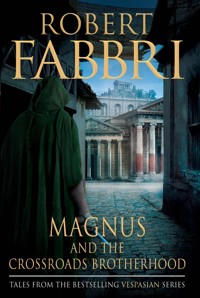

The complete collection of Robert Fabbri's Vespasian novella series about Magnus and the South Quirinal Crossroads Brotherhood. Marcus Salvius Magnus, leader of the South Quirinal Crossroads Brotherhood, has long dominated his part of Rome's criminal underworld. From rival gangs and unpaid debts to rigged chariot races and blood feuds - if you have a problem, Magnus is the man to solve it. He'll do everything in his power to preserve his grip on the less-travelled back alleys of Rome, and of course, make a profit. But while Magnus inhabits the underbelly of the city, his patron, Gaius Vespasius Pollo, moves in a different circle. As a senator, he needs men like Magnus to do his dirty work as he manoeuvres his way deeper into the imperial court... In these thrilling tales from the bestselling Vespasian series, spanning from the rule of Tiberius through the bloody savagery of Caligula to the coming of Nero, Robert Fabbri exposes a world of violence, mayhem and murder that echos down the ages. ______________________________________________ Don't miss Robert Fabbri's epic new series Alexander's Legacy

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

MAGNUSAND THE CROSSROADSBROTHERHOOD

Also by Robert Fabbri

THE VESPASIAN SERIES

TRIBUNE OF ROME

ROME’S EXECUTIONER

FALSE GOD OF ROME

ROME’S FALLEN EAGLE

MASTERS OF ROME

ROME’S LOST SON

THE FURIES OF ROME

ROME’S SACRED FLAME

EMPEROR OF ROME

ALEXANDER’S LEGACY

TO THE STRONGEST

STANDALONE

ARMINIUS: LIMITS OF EMPIRE

ROBERTFABBRI

MAGNUSAND THE CROSSROADSBROTHERHOOD

First published in eBooks in Great Britain in 2011, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2017, 2018 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This collection published in hardback in Great Britain in 2019 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Robert Fabbri, 2011, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2017, 2018

The moral right of Robert Fabbri to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

These short stories are entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 043 9eBook ISBN: 978 1 83895 044 6

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

This one is for Anja again, with all my love.

THE CROSSROADS BROTHERHOOD

I had not planned Magnus, he just stepped out into the road on the day that Vespasian and his family entered Rome in the opening book. I had originally intended Vespasian to rescue a brother and sister from the clutches of the Thracians later on in Tribune of Rome; their indebtedness to Vespasian for saving their lives would provide the basis for lifelong loyalty. But, instead, Magnus got up from his table outside the South Quirinal Crossroads Brotherhood’s tavern and waylaid the Flavian party. And I’m so glad that he did.

I immediately saw that with Magnus being a part of Vespasian’s story I could explore that part of Rome – the underbelly – which, because of his rank, I could not with my main character.

And so the South Quirinal Crossroads Brotherhood was conceived and Magnus, Sextus, Marius, Servius, Cassandros and Tigran, as well as other lesser characters, were born, along with Magnus’ arch-rival Sempronius and his West Viminal Brethren.

But Magnus needed to be attached to the higher echelons of society, otherwise who would have the influence to get him off the hook after another rampage through Rome behaving very badly indeed – badly at least to our modern way of thinking? So to make him a client of Vespasian’s uncle, Gaius Vespasius Pollo, and indebted to him for saving his life over a silly misunderstanding that left someone or other dead was an ideal way to have Magnus cross the divide between the two sides of Rome. Thus Magnus’ present difficulties in Rome’s underbelly could be solved at the same time as looking after the interests of his benefactor operating in far higher circles.

The final ingredient that I needed were subjects for the six stories that I planned; however, that was easy as the human condition does not change much – it was ever thus. And so each story deals with something that is still relevant today, and in the case of The Crossroads Brotherhood it is child prostitution. The Albanians that I mention are not the same as what we know of today but, rather, from the ancient Kingdom of Albania on the west coast of the Caspian Sea, next to, rather confusingly, Iberia!

This first story concerns what Magnus was doing in the lead-up to his first appearance in Tribune of Rome and finishes with his first line in said book; I have to admit that was my wife Anja’s idea and I can make no claim to it!

ROME, DECEMBER AD 25

‘MARCUS SALVIUS MAGNUS, I’ve come to you as my patron in the hope that you will right the wrong that is being done to me. In the three years that you have been the patronus of the Crossroads Brotherhood, here in the South Quirinal district, you have seen that I’ve always paid the not inconsiderable dues owed for your continuing protection in full and on time. I have always provided you with information on my clients, when you have asked for it. I have always offered you free use of my establishment, although you have never availed yourself of that, as my goods are not, I believe, to your taste.’

Magnus sat – leaning back in his chair with his elbows resting on the arms, his hands steepled, his forefingers pressed to his lips – and looked intently at the slight, auburn-haired man standing on the other side of the table as he continued to list examples of his loyalty to the Crossroads Brotherhood, under whose protection lived every trader and resident on the southern slope of the Quirinal Hill. Wearing a tunic of fine linen, outrageously unbelted, and with long, abundant hair tied back in a ponytail, he was of outlandish appearance, but not unattractive – if you liked that sort of thing. Although in his late thirties, his skin was as smooth as a young woman’s, clinging tightly to his fine-boned cheeks and jaw. His sea-grey eyes, lined with traces of kohl, sparkled in the soft lamplight and watered slightly in reaction to the smoky fug produced by the charcoal brazier in the small, low-ceilinged room that Magnus used to transact business with the more important of his many clients. Through the closed door behind him came the muffled shouts and laughter of the well-fuelled drinkers in the tavern beyond.

Magnus had no need to hear of the man’s commitment to him and his brothers, he already knew him to be trustworthy. What interested him was the fact that he felt compelled to affirm it at such length. He was evidently, Magnus surmised, building up to ask a very large favour.

Next to Magnus, his counsellor and second-in-command, Servius, shifted impatiently in his chair and scratched his balding grey hair. Magnus shot him a displeased glance and he settled, stroking the wrinkled skin sagging at his throat with a gnarled hand. Servius knew full well that a supplicant had the right to fully state his claim – however long-winded – to the protection of the only organisation in Rome that would look after the interests of his class.

‘And finally, I am always at your disposal to help repel incursions from the neighbouring brotherhoods,’ the man eventually concluded, causing Magnus to smile inwardly at the thought of such an effeminate in a street fight, ‘should they try to take what is rightfully ours – as they did, not one hour ago.’

Magnus raised his eyebrows, concern seeping on to his battered, ex-boxer’s face – this was unwelcome news. ‘You’ve been robbed, Terentius? By whom?’

Terentius pursed his lips and almost spat on the floor before remembering where he was. ‘Rivals from the Vicus Patricius on the Viminal.’

‘What did they take?’

‘Two boys, and they cut up two others; one very, very badly.’ Terentius looked down and indicated to his groin. ‘You understand?’

Magnus winced and then nodded thoughtfully. ‘Yeah, I take your meaning. You did right to come to me. Who are these rivals?’

‘They aren’t citizens – they came from the east a few years back.’

Magnus looked at Servius in the hope that his counsellor’s long lifetime’s supply of knowledge of the Roman underworld would extend to these easterners.

‘They’re Albanii,’ Servius informed them, ‘from the kingdom of Albania in the south-east Caucasus between Armenia and Parthia on the shores of the Caspian Sea. Like a lot of eastern barbarians they’re inordinately fond of boys.’

Magnus grinned. ‘Well, there’s a big market for them here as well. I can understand why they’ve set themselves up in competition to you, Terentius. Have you lost much business to them?’

Terentius looked at the chair in front of him and then back at Magnus, who nodded. With a grateful sigh he sat down – not used to being upright for so long, Magnus mused with a hint of a smile.

‘It was fine for the first couple of years,’ Terentius said, taking the cup of wine that Servius offered. ‘They were no threat to me: cheap with substandard, dirty boys who took no pride in their appearance. And besides, the house was more than half a mile away. But what it lacked in class and service it made up for with turnover.’

‘A quick in and out, as it were?’

‘What? Oh yes, I see. Well, they worked their boys hard, day and night, and soon were making good money but still they didn’t trouble me as their clients were from the lowest part of society. I kept my elite clientele: senators, equestrians and officers of the Praetorian Guard, some of whom still occasionally ask for me.’ Terentius smiled modestly and smoothed his hair with the palm of his hand.

‘I’m sure that a professional with your experience is a sound investment for an evening,’ Servius commented diplomatically, his hooded eyes betraying no irony.

Terentius inclined his head slightly, acknowledging the compliment. ‘I do not disappoint and neither do my boys.’ He took a delicate sip of wine. ‘However, at the beginning of this year these Albanians decided to move upmarket, competing directly with me; and by this time they could afford to. They bought a more lavish place, close to the Vinimal Gate, and began to stock it with the best boys that they could find.

‘As a result of Tacfarinas’ revolt being crushed last year, the slave markets had started to fill up with the most delicious boys from Africa and, naturally, I wanted my pick of these brown-skinned beauties.’

‘Naturally,’ Magnus agreed.

‘Unfortunately so did my rivals and, regrettably, they too have good taste. I suggested an agreement with them whereby we wouldn’t always bid against each other, but they refused. Even on the very young ones that we train up so they are able to do most things with finesse by the time they’re starting puberty; you can charge a premium for them. I couldn’t let all the best ones go: my stock would have deteriorated over the next few years whilst theirs went up – I would lose my standing. So, I bid over the odds for the best.’

‘Which must have pissed off our Albanian friends no end,’ Magnus observed.

‘Yes, but they still ended up with a goodly amount of beautiful, if over-priced, young flesh, and because the Praetorian Guard’s camp is just outside the Viminal Gate, I started to lose some trade. I had little choice but to lower my prices and do deals: two for the price of one, eat and drink for free on your second consecutive evening, and that sort of thing. But they responded with similar policies and now, because of the huge outlay that we’ve both made this year, we’re slowly driving each other out of business and, what’s more, our clients all know it so they bargain even harder when they walk through the door.’

Magnus shook his head; he could see the problem: if Terentius’ business went under then the South Quirinal Brotherhood would lose quite a chunk of its income. ‘And so this evening the Albanians decided to up the stakes and try and force you out.’

‘My men beat them off but the damage to my reputation is done; there were quite a few clients in the house when we were attacked.’

‘So you want me to negotiate a financial settlement with Sempronius, Patronus of the West Viminal?’

Terentius’ pale eyes hardened. ‘No, Magnus, this is beyond that now. I want you to get my two boys back and then I want you to destroy these Albanians. Kill them all and their boys. The money that I’ve paid over the years to this Brotherhood entitles me to that.’

Magnus looked at Servius and shrugged. ‘He’s got a point, Brother; and besides, we can’t let an attack like that in our area go unpunished – but how do we do it without starting a war?’

The counsellor thought for a few moments, looking at Terentius. ‘How well protected are these Albanians?’

‘They have the best protection: the Vigiles. One of their tribunes has been using the Albanians as a way to ingratiate himself with the Praetorian Guard. So the Vigiles ensure there’s never any trouble near the house and provide an escort for the boys to and from the Praetorian camp should an officer wish to enjoy them in the comfort of his own bed and suchlike services.’

Magnus stared hard at Terentius and sucked in his breath through his teeth. ‘This is a big favour. If we do it we’ll have the Vigiles and the Praetorians as well as the West Viminal Crossroads after us.’

Servius smirked coldly. ‘You’ve got it, Brother: If we do it. We’ll just have to make sure that it looks like we didn’t.’

Magnus turned slowly to his counsellor; a trace of a smile cracked his lips. ‘You’re right. So first we need to get Terentius’ two boys back and bring the matter to an honourable conclusion so everyone can see that we have no more interest in it. Then we set someone else up.’

Terentius bowed his head in gratitude. ‘Thank you, patronus.’

Servius looked thoughtfully at his fingernails. ‘And who will seem to be responsible for the Albanians’ demise, Brother?’

‘It has to be a group that’s untouchable but one that could logically have done it. People who hate both the Vigiles and the Guard as much as they’re hated by them in return.’

Servius raised his eyebrows. ‘Your old mates?’

‘Exactly; the Urban Cohorts. I think that we should call a meeting of all the neighbouring brotherhood chiefs for tomorrow.’

‘I think so too. And I think that we should take a gift to show our good intentions.’

‘I’ll leave you in charge of the arrangements, Brother.’

‘I’ll send the invitations out immediately. Usual time and place?’

‘Usual time and place.’

*

Magnus was woken by a knock on the door of the small room that he called home, above the tavern that was the headquarters of his Brotherhood.

‘Magnus?’ a voice called from beyond the door.

‘Yeah, what is it? It’s still dark,’ Magnus replied sleepily, feeling the warmth of a woman in the bed beside him and trying to recollect her name.

‘It’s Marius, Brother. Servius says that you should come down and take a look at what Sextus, me and some lads brought in just now.’

Magnus grunted and eased out a fart. ‘All right, bring me a lamp.’

The door swung open and the silhouetted bulk of Marius filled its frame with a lamp in his right hand – his left hand was missing.

‘Leave it on the table, Marius,’ Magnus said, sitting up.

As Marius walked across the room Magnus pointed to the sleeping form beside him and mouthed: What’s her name?

‘Dunno, she’s new, just turned up last night.’

‘Thanks, Brother, very helpful. I’ll be down in a moment.’

Magnus slapped the woman’s arse and got out of bed as Marius left the room. ‘Up and at ’em, my girl. I’ve got to go. What do I owe you?’

The woman rolled over sleepily and peered at him through a tangle of well-ravaged black hair. ‘It was a free one, Magnus. Aquilina, remember? I said I’d do you for free if you’d let me work the tavern.’

‘Ah, that’s right, you’re new,’ Magnus replied, trying to remember the conversation through the haze of last night’s wine. ‘Well, you’ve passed the test. See old Jovita later and tell her that I said it was fine for you to work here. She watches the girls; you report to her if you leave with a customer or if you’re just giving your favours in a dark corner. We take twenty per cent of everything you earn from the tavern, payable in cash the following morning. If you try and cheat us, you’re out on your ear and you won’t find a cock willing to service you in this district ever again, not even for nothing, because you’d be too ugly, if you take my meaning?’

Aquilina smiled, getting to her feet – a pretty smile Magnus thought, she should do well. ‘I won’t cheat you, Magnus, I just want to earn my keep,’ she said, slipping on her tunic and picking up her discarded loincloth and sandals. She gave him a kiss on the cheek. ‘Any time you want me, I won’t charge.’ Giving him a playful squeeze, she left the room.

Magnus watched her go, frowning.

‘What’ve we got here then that’s so important?’ Magnus asked, walking into the tavern’s main parlour that still stank of stale wine, vomit and sweat from the previous evening.

Servius looked up from a scroll of accounts that he was going through on a table in the centre of the room and nodded towards two small figures, bound with sacks over their heads, slumped under the amphorae-lined bar. Marius and Sextus watched over them.

‘Servius sent us fishing,’ Sextus said slowly, as if reciting, ‘and we caught a couple of slippery fish. They’re nice and greasy, especially in certain places.’ He broke into deep, shuddering laughs.

Marius smiled at Magnus, shaking his head in exasperation. ‘He’s been practising that line for the last hour, Magnus; it ain’t even funny ‘cos fish are slimy not greasy, but he can’t see the difference.’

‘Well, he’d soon find out if he came across a slimy arse. Let’s have a look at them.’

With Sextus incapacitated by mirth, Marius pulled the sacks off, to reveal two very attractive, but slightly bruised, brown-skinned youths in their early teens. They looked at Magnus with dark, fearful eyes and huddled closer together.

‘The lads did well, Magnus,’ Servius observed.

Magnus was impressed. ‘A couple of the Albanians’ boys? How did you get them, Marius?’

‘They was on their way back from a visit to the Praetorian Camp.’

‘But they have an escort of Vigiles.’

‘Yeah, but what do Vigiles do when they see a fire?’

Magnus grinned. ‘First they negotiate a fee with the owner for putting it out; then they put it out.’

‘So I had some of the lads start a fire when we knew they was on their way, and these poor little fish got forgotten about whilst their minders tried to make a profit out of some poor bastard’s misfortune. So Sextus and me decided to escort them home. We just took a few wrong turns, that’s all, and happened to end up here.’

‘Well done, lads; such a pretty gift for the meeting later. Lock ‘em up safely until this afternoon and then get the altar ready for the morning sacrifice.’

Marius visibly swelled with pride at the praise and he and Sextus, who was still chuckling fiercely, hauled the terrified boys to their feet and dragged them away.

Magnus turned to Servius. ‘Have the invitations gone out?’

‘Yes, Brother, and all the replies are back in. All five of the surrounding Patroniae will be there an hour before sunset.’

The sun was slipping behind the Aventine Hill throwing the raked-sand track of the Circus Maximus into shadow and bathing the stepped-stone seating and the colonnades that soared above in a warm evening glow.

Magnus stood, in a freshly chalk-dusted white toga, at the end of the spina, the central barrier that ran down the middle of the track, facing the massive wooden gates that opened out on to the Forum Boarium. Servius, flanked by Marius and Sextus, waited behind him – they too sported gleaming togas, worn with pride by the free and freed citizens of Rome, however lowly, and worn today, as custom decreed, at a meeting of Crossroads Patroniae. Four other similar groups of a patronus, his counsellor and two bodyguards, stood around the edge of the track, two to Magnus’ left and two to the right, all keeping a good distance between each other as they awaited the final arrival. A light breeze, blowing along the length of the track of the eerily silent stadium, played with the folds of their togas.

‘Fucking typical of Sempronius to keep us waiting so that he can make a grand entrance,’ Magnus muttered over his shoulder to Servius.

‘A futile gesture, Brother; you will all be equal in the middle, no matter who arrived last.’

Magnus grunted. A moment later a small door to the left of the main gates swung open to reveal the missing party led by a tall, blond-haired, young man. As he started to walk forward, Magnus and the other four Patroniae, followed by their entourages, did the same, coming to a halt in a circle exactly halfway between the spina and the gates, one of the few public places in the crowded city of Rome where a private conversation could be held without fear of eavesdroppers.

‘Greetings, Brothers,’ Magnus said, looking each of his counterparts in the eye. ‘I, Marcus Salvius Magnus, of the South Quirinal, called this meeting to deal with an issue that has arisen between us and the West Viminal Brotherhood.’

Sempronius pursed his lips, pulled his broad shoulders back and glared at Magnus with cold, piercing, sapphire-blue eyes; the jaw muscles beneath the tight flesh of his cheeks twitched rapidly. His counsellor, equally young and equally handsome but dark-haired, leaned forward and whispered in his ear. Sempronius nodded, never once taking his eyes off Magnus.

‘I wish to settle this issue now,’ Magnus continued, ‘in front of witnesses, in order to avoid it escalating into a war. None of us here would wish to see that, as we all know from past experience just how damaging for business that can be.’

Sempronius looked down at his left arm, held rigid across his stomach, supporting the folds of his toga, and stared at it for a few moments as if examining in fine detail the blond hairs on the back of his hand. His eyes suddenly flicked back up to Magnus. ‘We had nothing to do with the raid on the whore-boy house.’

‘I am not saying that you did; yet you know about it.’

‘I know of it,’ Sempronius corrected, ‘but not much about it. As I said: it was not done by us.’

‘No, but it was done by people from your area; Albanian clients of yours, who you would be honour-bound to avenge if we exacted the correct price for their actions.’

‘And what would you consider that price to be?’ Sempronius asked slowly, one side of his face curled up in a sneer.

‘Death. And not a quick one.’

Sempronius smiled mirthlessly. ‘That would be grievous mistake.’

‘No, Brother, that would be justice, but I’m not naive enough to think that we both have the same sense of justice so, in order to maintain the peace between us, I offer this compromise.’ Magnus put two fingers in his mouth and whistled shrilly. A couple of his lads led two small figures out of one of the entrance tunnels in the rows of seating; knives were held across their throats.

Sempronius regarded them for a few moments and then shrugged. ‘More whore-boys; what are they to me?’

‘They’re nothing to you, but they’re worth quite a bit to their Albanian owners – in the condition that they’re in at the moment, that is. Unfortunately their condition is worsening.’ Magnus raised a hand and brought it down quickly. A knife flashed golden in the evening sun; there was a screech and blood started to flow down the face of one of the boys. ‘That was just a small cut across the top of his forehead; nothing too disfiguring so it won’t reduce his value that much.’

‘What do you want?’

‘The two boys that your Albanian friends took from my client. If they are returned tonight, unharmed, then I will return those two with their fingers, tongues and cocks still in place and without sharp knives rammed up their arses. In other words, in perfect working order to carry on their trade. My client will also forgo his revenge for the two other boys that were cut up in the attack and that will be an end to the matter.’

‘And if they’re not returned tonight?’

‘It will be their tongues first, then we’ll have our vengeance on the Albanians and all our businesses will suffer as we fight out a blood-feud.’

‘That can’t be allowed to happen, Sempronius,’ the patronus to Magnus’ left stated. ‘My area, the North Viminal, is right between you two, we would suffer badly. Magnus’ deal is fair and you should accept it; if not and you take us to war, then we will be against you.’

There were murmurs of agreement from the other three Crossroads leaders.

Magnus kept his expression neutral but smiled inwardly as anger briefly flashed across Sempronius’ face; he would have to back down and lose face or find himself ranged against all of the brotherhoods on the Viminal and Quirinal.

‘Give him something to take away from the meeting as a sop,’ Servius whispered into Magnus’ ear. ‘Otherwise his pride may prevent him from accepting.’

Magnus nodded. ‘To show our goodwill, Sempronius, I’ll give you one of the boys to take with you now, on account as it were.’

Sempronius turned to his counsellor who inclined his head indicating his agreement. ‘Very well, Magnus, I’ll take the boy. The Albanians will return the two that they’ve got this evening and pick up the second one then. After that we’re square, yes?’

‘Square, Sempronius, and these brothers are our witnesses. Tell your Albanians to have the boys at my tavern by midnight, I’ll guarantee their safe conduct. After that they’re to keep out of my area if they value their lives.’

It was dark by the time Magnus and his comrades got back to the Crossroads; the tavern was filling up and business was brisk.

‘Take him into the back, clean him up and keep watch over him, Cassandros,’ Magnus ordered one of the two brothers accompanying the visibly terrified remaining whore-boy. Dried blood matted his hair and covered his face.

‘A pleasure, Magnus,’ Cassandros replied with a grin.

‘And keep your filthy Greek hands off him, and any other part of your body for that matter: he’s not to be interfered with.’

Looking disappointed, Cassandros led his charge off as Magnus and Servius took a corner table. A jug of wine and two cups were quickly set before them by a plump, grey-haired woman.

‘Business looks good this evening, Jovita,’ Magnus commented as she filled his cup.

Jovita indicated with her head to the far corner where Aquilina was perched on the lap of a busy-handed freedman. ‘That new one who started today seems to be very popular; seems to be pulling a crowd. That’s number six so far.’

‘Busy girl,’ Servius commented to the old woman’s back.

Magnus looked away from the girl, taking a slug of wine. ‘So, Brother, they seemed to believe us.’

‘Yes. So now we wait.’

‘Just a few days, let things settle.’

‘Have you worked out how we’re going to do it?’

‘Almost, there’re a couple of things that I ain’t sure of yet but I’ll go and see an old comrade from the Cohort discretely tomorrow; he’ll be able to help me.’

Servius looked over Magnus’ shoulder. ‘Not another whore-boy?’

Magnus turned to see a beautiful youth in his early teens swathed in a hooded cloak and sighed. ‘Does he want to see me, Arminius?’

‘Yes, master, can you come at once?’ the youth replied with a guttural Germanic accent, pulling back his hood to reveal luxuriant, flaxen hair.

Magnus nodded and downed his wine. ‘Deal with the exchange if I’m not back when the Albanians arrive, Brother.’ He got to his feet and, indicating to Marius and Sextus that they should follow him, stepped out into the night after the young German.

‘Magnus, my friend, thank you for coming so quickly,’ Gaius Vespasius Pollo boomed, turning his huge bulk in his chair as Magnus and his companions were shown into the atrium by a very decrepit and ancient doorkeeper. ‘Arminius, take Magnus’ friends to the kitchen and find them some refreshment.’

‘Good evening, Senator,’ Magnus replied as his erstwhile guide led Marius and Sextus from the room.

‘Come and sit down, it’s a chill night.’ Gaius indicated with a full wine-cup to a chair across the table from him, in front of a blazing log fire, set in the hearth.

‘How can I be of assistance at this time of night?’ Magnus asked, sitting and adjusting his toga.

Gaius handed him the cup. ‘Yes indeed, not really the business time of day, is it?’

‘It is for my sort of business.’ Magnus took a long draught of wine, ignoring Gaius’ disapproving frown at the rough treatment of such a fine vintage. ‘That’s a nice drop of wine that is, sir.’

‘I’m glad that you appreciate it.’ Gaius reluctantly topped up Magnus’ proffered cup. ‘What do you know about the Lady Antonia?’

Magnus shifted uneasily in his chair and took another slug of wine. ‘She’s the Emperor’s sister-in-law, grandmother to the children of the late Germanicus and a very formidable woman. I believe that you are in her favour.’

‘I am.’

‘When I was a boxer I attended a few of her dinners as a part of the entertainment.’

‘Yes, I’m aware of that, although I’ve never understood why a citizen would choose to become a boxer.’

‘The money mainly but also the notoriety – look at all them young gentlemen who choose to fight a bout or two in the arena for wagers or just to get their names heard.’

‘Rather excessive, to my mind.’

‘Yeah, well, it helped me become the patronus of my Crossroads – you don’t do that by just asking nicely, if you take my meaning?’

Gaius’ eyes twinkled with amusement in the glow of the fire. ‘No, you did that by murder for which you would have paid with your life – had it not been for me, if you take mine?’

‘I do, Senator, and I will always be in your debt.’

‘Enough to commit another murder?’

Magnus shrugged and held out his cup for another refill. ‘If you require it.’

‘I don’t,’ Gaius emphasised, pouring more wine, ‘but Antonia does. This evening she asked – or rather ordered – me to organise one for her. She’s not a woman that one can say no to.’

Magnus looked away and tried to keep his face neutral. ‘I can imagine.’

Gaius chuckled, causing his tonged ringlets to sway gently over his ears; he took another sip of wine.

‘Who does she want done and why doesn’t she organise it herself?’ Magnus asked.

‘There’s absolutely no reason why she couldn’t organise it herself, so I’ve a hunch that the answer to the second question is that it’s a test to see how far she can trust me. If I succeed then I will have a place in her inner circle of friends.’

‘And be one step closer to the consulship.’

‘Quite. So you can see how important it is for me. As to the first question, that’s simple: a Praetorian Guardsman.’

Magnus banged his cup down on to the table in alarm. ‘A Praetorian? Is she serious?’

‘Oh yes, quite literally deadly serious. And it’s not just any Praetorian either, it’s Nonus Celsus Blandinus.’

‘Blandinus? One of the tribunes?’

‘I’m afraid so.’

‘What’s she got against him?’

‘Nothing that I know of; it’s rather unfortunate for him really.’

‘Then why?’

‘Earlier this year, Antonia managed to persuade the Emperor to forbid the Praetorian Prefect Sejanus to marry her widowed daughter, Livilla. Now she wants to send a message to Sejanus that in making that request he went too far; and what better way to do that than to have one of his deputies killed?’

‘I can think of a lot of better ways. When does she want it done?’

‘Within the next couple of days. But she wants it done in a way that Sejanus will know that she’s behind it but be unable to accuse her of organising the murder.’

‘So we can’t just slit his throat in a dark alley.’

‘Absolutely not, this demands subtlety.’ Gaius leaned forward and put his hand on Magnus’ forearm. ‘I’m relying on you, my friend. If you do this well for me then Antonia will owe me a favour. My sister and brother-in-law are bringing their two boys to Rome. I may be able to use this to have her further their careers as well as my own.’

Magnus raised an eyebrow at his patron. ‘And the higher you and your family rise the more you can do for me, eh, Senator?’

‘Naturally.’ Gaius smiled and patted Magnus’ arm. ‘We could all come out of this very well.’

‘You might, but I could come out of this very dead.’

‘If I thought that for one instant then I wouldn’t have entrusted you with one of the most important favours of my career,’ Gaius asserted, raising his cup to Magnus who smiled mirthlessly, raised his in reply and then downed it in one.

The night was cold and clear; Magnus’ breath steamed as he walked, deep in thought, down the quiet streets of the Quirinal followed by Marius and Sextus. Turning left on to the wider and busier Alta Semita, jammed with the delivery wagons and carts that were only allowed into the city at night, the pavement became more crowded but people stepped aside in deference as they recognised the leader of the area’s Brotherhood. Those who were not local and failed to move were roughly shoved out of the way by Marius and Sextus.

Magnus accepted a charcoal-grilled chicken leg from the owner of one of the many open-fronted shops, occupying the ground floor of the three- or four-storey insulae that lined both sides of the street. The walls to either side of the shop were covered in graffiti, both sexual and political.

‘Thank you, Gnaeus; one for each of the lads as well.’

‘My pleasure, Magnus,’ the sweaty store-holder replied, retrieving, with a pair of tongs, two more legs off the red-glowing grill.

‘Business been good?’ Magnus asked, biting into the dripping flesh.

‘We had a very good Saturnalia, however it’s trailed off a bit in the last few days but I’m sure that it will pick up for the New Year. The trouble is that the price of fresh chicken has gone up considerably in the last couple of months and it’s eating into my profit.’

‘And you’ve raised your prices as much as you can?’ Magnus asked, realising why Gnaeus had offered him some of his wares.

‘As much as I dare without pricing myself out of the market.’

‘Where do you buy your chicken?’

‘Ah, that’s the big problem: the small market at the Campus Sceleratus, just inside the Porta Collina; the prices are usually better there than in the main Forum markets, and it’s in our area. However, I’m sure that the traders have started fixing their prices and the market aedile is colluding with them.’

‘I see.’ Magnus gnawed thoughtfully on his chicken leg. ‘That sounds less than legal to me. I’ll send a couple of the lads up there tomorrow. They can offer anyone I suspect of price-fixing the opportunity of joining the Vestals who were buried alive beneath that Campus for breaking their vows.’

Gnaeus inclined his head in gratitude. ‘I’m sure that’s an offer they would be happy to refuse, thank you, patronus.’

Magnus threw his cleaned bone into the gutter. ‘How’s that daughter of yours? Have you found her a husband yet?’

Gnaeus raised his eyes to the heavens. ‘The gods preserve me from wilful women. I—’

A series of loud shouts from a nearby shop interrupted the store-holder’s catalogue of domestic woes. A bearded young man came pelting along the pavement towards them, clutching two loaves of bread to his chest.

‘Marius? Sextus?’ Magnus said, stepping aside and nodding at the fast approaching thief.

Seeing his path blocked by two burly men in togas, he tried to sidestep to his left, into the road. Sextus thrust out his massive, right fist and caught him a stunning blow to the side of his head, sending him crashing into a mule-cart and startling the beast pulling it. With a speed that belied his size and quickness of thought, Sextus was down on the stunned man, hauling him up by his ragged tunic, semi-conscious, to his feet; the loaves of bread were left in the road to be trampled by the spooked animal.

A tubby little baker in a grease-specked tunic puffed, pushing his way through the gathering crowd of onlookers. ‘That man stole from my shop, Magnus. I want payment for that bread.’

Magnus walked over to the still-dazed thief held upright in Sextus’ powerful grip. He lifted his chin roughly in his hand, squinting at his face. ‘I don’t recognise him, he ain’t from round here.’ Letting his chin go he gave him an abrupt slap across the cheek. ‘Where’re you from, petty thief?’ The man’s head lolled on his chest, a trickle of blood worked its way through his beard; he said nothing.

Magnus grasped the captive’s right hand, folding his fingers in a firm grip, crushing them, causing a groan of pain as he recovered his senses. ‘What are you doing stealing from this area?’

The man opened his eyes and tried to focus on Magnus, his face grimacing with agony as the pressure increased on his crushed fingers. ‘He cheated me couple of days ago,’ he managed to whisper, in thickly accented Latin. ‘He gave me a counterfeit as in change.’

Magnus eased his grip. ‘Can you prove that?’

The man reached for his belt and pulled a small copper coin from a leather pocket sown into the reverse side. Magnus looked at it; the surface had been scratched revealing the dull-metallic hue of iron. He took the coin and brandished it at the baker. ‘Did you give him this, Vitus?’

The baker reddened and held up his hands. ‘Of course not, Magnus, I wouldn’t be so stupid; I’m well aware of the punishment for passing dud coinage.’

‘I think that I had better have a look in your shop. Marius, ask this gentleman nicely to escort us to it.’

‘My pleasure, Magnus,’ Marius said, stepping forward and placing a firm hand on the reluctant Vitus’ shoulder, slowly turning him around; he pushed his stump into the small of the baker’s back and propelled him forward the few paces to his open-front shop.

Sextus followed, hauling the thief after him.

‘Where do you keep your money, Vitus?’ Magnus asked, looking around the shelf-lined premises and enjoying the smell of freshly baked bread.

Vitus glanced sidelong at his accuser, still secure in Sextus’ grip. ‘There, under the oven.’ He pointed to a recess below a sturdy iron door. Next to it two elderly female slaves were kneading dough on a wooden table. They continued with their work, ignoring the intrusion.

‘Show me.’

Vitus retrieved a wooden box from behind a couple of full, small sacks and opened it; it was a quarter filled with low-denomination coins.

‘That’s not where he got my change from,’ the thief exclaimed. ‘One of the slaves got it from a bag in a draw in the table.’

The two women stopped the work and looked at their master, who paled.

Magnus smiled grimly at the baker and held out his hand. Vitus nodded at one of the women who opened a draw, pulled out a small leather bag and threw it to Magnus.

‘Well, well, Vitus,’ Magnus said as he tipped a dozen or so coins into his hand, ‘evidently you are stupid; lucky that it was me that caught you and not an aedile.’

Vitus fell to his knees and clutched at the hem of Magnus’ toga. ‘Please, Magnus, don’t report me to the aedile; I’ll lose a hand. I’m sorry, I won’t do it again.’

‘Too fucking right you won’t do it again; I won’t have it in my area; it will give us all a bad name.’ He turned to the thief. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Tigran, master.’

‘Where’re you from?’

‘Armenia, master.’

‘No, I meant: where are you from in Rome?’

‘Oh, I live in the shanty town amongst the tombs on the Via Salaria.’

‘You’re not a citizen, are you?’

‘No, master. I arrived here a few months ago.’

‘Then I’ll give you a warning: you don’t steal here. Next time you’re cheated in my area come and see me, I won’t have people taking the law into their own hands. Explain that to him, Sextus.’

With a sharp jab, Sextus rammed his right fist into Tigran’s stomach, doubling him over with a loud exhalation of breath.

Magnus put the counterfeit coins back into their bag and tucked it into the fold of his toga. ‘Get me two loaves of bread, Vitus.’ As the baker rose to his feet and scuttled to a shelf Magnus removed four asses, the equivalent of one sesterce, from the money box and gave them to Tigran, who still struggled for breath. ‘Give him the bread as well, Vitus.’

Vitus quickly handed over the loaves.

‘Now get out of here and don’t come back unless you plan to behave honestly,’ Magnus said, cuffing Tigran around the ear.

‘Thank you, master.’ Tigran turned quickly to go, clutching the loaves to his chest with one hand and clasping his money in the other. He pushed through the crowd of onlookers and disappeared.

‘As for you,’ Magnus growled, pulling Vitus by the collar so that their faces were nose to nose, ‘I want a list of everyone that you can remember passing that shit on to, plus the name of the person who supplied it, with me by morning, or it will be your last, if you take my meaning?’ He brought his knee sharply up into Vitus’ testicles and then walked away leaving the baker to crumple to the floor, eyes bulging, unable to breathe and with both hands grasping his damaged genitals. The crowd parted for him, voicing their approval having witnessed justice well done.

Magnus and Servius sat at a table in the shadowy, smoky confines of the small room behind the tavern that they used to conduct business. A jug of steaming hot, spiced and honeyed wine stood between them next to a single oil lamp. ‘So we need to kill a Praetorian Tribune in a way that doesn’t look like an accident and doesn’t look like an obvious murder but is suspicious enough for Sejanus to recognise it as a warning from Antonia,’ Servius summarised.

Magnus looked gloomy. ‘That’s about it, Brother. How the fuck can we do that?’ He took a swig from the cup that he held in both hands and scalded his tongue.

Servius looked on with amusement as his superior called on various gods to curse or strike down the obviously half-witted slave who had prepared the wine. ‘I think that was a good lesson,’ he observed once the tirade had subsided. ‘Drink the wine before it’s ready and it will hurt you; drink when it’s just right and it will please you. So let’s not rush into this—’

‘But we have to rush into this,’ Magnus interrupted – the burn had not helped his temper. ‘Antonia wants this done in the next couple of days.’

Servius raised a calming hand. ‘Yes, and it shall be. All I’m saying is that at the moment we don’t know how to approach it. The difference between an accident, death in suspicious circumstances and murder is the situation in which the body is found. A man may die falling from a horse that he rides every day; he may genuinely have fallen off, in which case it is an accident; or the horse may have been spooked on purpose by someone in order to get it to throw the man off, in which case it’s murder. However, if a man is found dead having fallen from a horse but it’s known that he never goes riding, then that’s death in suspicious circumstances; it would be highly unlikely to be an accident because what is he doing on the horse in the first place? And yet you can’t prove that it’s not; nor can you prove that it was murder because people die all the time from falling off horses.’

Magnus’ face brightened; the pain from his burnt tongue forgotten. ‘Ah! So you’re saying that if we stage an “accident” whilst Blandinus is apparently doing something that he never normally does then Sejanus will suspect it was murder but be unable to prove it.’

‘Exactly.’

‘So we need to use the rest of tonight and tomorrow to find out all that we can about the unfortunate tribune.’

‘Precisely, and then we will have to somehow lure or force the poor man into that unusual circumstance in which he will be found dead.’

‘Tricky but not impossible. Get the lads on to it immediately.’

‘I will, Brother,’ Servius confirmed as a knock sounded on the door.

‘Yes?’ Magnus called.

Marius stuck his head into the room. ‘Magnus, they’re here waiting outside, them Albanians, and a strange fucking sight they are too.’

‘I don’t care what they look like, so long as they’ve got the boys.’

‘Yeah, they got them all right.’

‘Good. Go and tell Cassandros to bring the boy into the tavern; I’ll send for him when I need him.’ Magnus rose to his feet. ‘Shall we go and do business, Brother?’

‘I think we should,’ his counsellor agreed, following him out.

Magnus surveyed the four bizarrely attired easterners waiting in the moonlight by the tables outside the tavern. Two pretty youths in their early teens, one with blond hair and one dark, stood next to them, staring at Magnus with frightened eyes, knives held to their throats.

‘Who speaks for you?’

‘I do,’ a middle-aged man said, stepping forward. He wore a long-sleeved, saffron tunic, belted at the waist, that came to just below his knees, half covering a pair of dark-blue baggy trousers bunched in at the ankle to expose delicate, red-leather slippers. His oiled hair was jet black and fell to his shoulders framing a lean, high-cheekboned face dominated by a sharp, straight nose. Two dark, mirthless eyes stared back at Magnus; his thin mouth was just visible beneath a hennaed red beard that came to an upwards-curling point.

‘And you are?’ Magnus asked, trying to keep the contempt that he felt for this outrageous-looking whore-boy master out of his voice. Behind him Sextus and Marius led half a dozen brothers, armed with knives and cudgels, out of the tavern.

‘Kurush,’ the Albanian replied, resting his right hand on the hilt of a curved dagger hanging at his waist. ‘And you must be Magnus?’ His Latin was precise and with little trace of an accent.

‘I am. Let’s get this over with; show me the two boys.’

‘They have not been harmed or even interfered with; I can assure you of that with my word.’

‘I’m sure you can but, nevertheless, I wish to see them closer.’

‘A man who won’t take another man’s word is not worthy of trust himself. Let me see my boy. His condition will determine the state of the other two.’

‘Sextus, tell Cassandros to bring him out,’ Magnus ordered, keeping his eyes locked on Kurush.

They waited in silence, staring at each other, for the few moments that it took Cassandros to appear with his charge.

‘Bring him here,’ Magnus said as the Greek dragged the struggling youth through the tavern door.

‘This man raped me,’ the whore-boy shrieked at Kurush, pointing an accusatory finger at Cassandros, ‘and paid nothing.’

Magnus spun round. One look at Cassandros’ face confirmed that the boy was telling the truth: he could not meet his eye.

‘It would seem that we have a problem,’ Kurush observed. ‘I don’t take kindly to people making free with my property.’

Magnus grabbed the youth from Cassandros’ grasp with his left hand and cracked his right fist into the Greek’s face, felling him. ‘I’ll take care of it once we’ve done the exchange; he’ll be punished, I give you my word.’

‘Why should I take your word when you wouldn’t take mine just now? But I’m not interested in him being punished, you can do what you like to him; I’m interested in a fair exchange.’

‘This is a fair exchange, more than fair. I’ve already given you one of your boys; let’s complete the transaction and then we need have nothing more to do with each other.’

Kurush smiled icily and turned to his three companions speaking to them in their own language. The blond-haired boy was brought forward. Kurush took him by the neck and propelled him towards Magnus. ‘There, an untouched boy in payment for the one you sent me earlier.’

The boy stumbled and fell at Magnus’ feet. Marius stepped forward, hauled him up and pulled him away.

Kurush looked back at Magnus. ‘Now that leaves us with another untouched boy to exchange for a soiled boy; I don’t consider that fair.’ He barked a command in his own language.

The dark-haired boy was forced down over a table. He started to shriek as two of the Albanians grabbed his arms, holding them firm, at the same time pressing their weight down on his back, pinning him. The third Albanian, a young, effeminate-looking man with a wispy beard, barely out of his teens, pulled up the boy’s tunic and ripped off his loincloth, raised his own tunic and opened the flap in the groin of his trousers, his gaze never leaving the boy’s exposed buttocks. The boy screamed as the Albanian forced himself into him. The screaming stopped and the boy stared down at his white-knuckled hands gripping the table’s edge as the Albanian took to his task with all the savagery of the abused that has become the abuser.

Magnus stood and watched in silence, indicating to his men that they should do so too, knowing that to interfere would jeopardise the deal; Kurush was not a man to lose face and besides, it was nothing to him whether the boy was raped or not, the important issue was to get him back to Terentius unmarked, his value intact if not his dignity.

‘Is this absolutely necessary, Kurush?’ Magnus asked as the Albanian quickened his pace and grunted to a climax.

‘Yes, Magnus, for two reasons: firstly to show you that whatever is done to me or mine will be repaid in full, and secondly, to demonstrate that my men do as they’re told.’ He pointed down to Cassandros still lying prone on the ground. ‘Unlike yours.’

After a few moments collecting his breath, the Albanian withdrew and wiped himself clean on the boy’s tunic, grinning at Magnus as he did so.

‘Very educational I’m sure, you’ve made your point. Now take your boy and give me mine.’

Kurush barked another order and the boy was immediately released, grimacing with pain and clutching his loincloth. Magnus pushed Kurush’s boy towards him and as the two passed each other they paused for a moment, sharing a look of mutual sympathy, before carrying on back to their enslaved lives over which they had no control or say and in which the best that they could both hope for was to get through each day with as little misery as possible.

‘Now get out of my area by the quickest route,’ Magnus growled at Kurush as the boy passed him. ‘The offer of safe conduct doesn’t extend to any sightseeing. If you ever go near Terentius’ house again you’ll be a dead man, no matter who protects you.’

‘I think Terentius understands, well enough to make a second visit unnecessary, that there is only room at the top end of the market for one of our establishments.’

‘I know he does,’ Magnus muttered under his breath as the Albanians turned and left. ‘And so do I.’

‘Do we have anything interesting on our tribune yet?’ Magnus asked Servius. They were making their way in the crisp and clear dawn air up the Via Patricius, one of the main thoroughfares of the Viminal. Cloaked and deeply hooded to avoid being recognised, they had especially chosen this chill time of day so that their attire would not stand out as suspicious.

‘Nothing yet,’ Servius replied from within the depths of his hood, ‘but it’s only been one night; give the lads time. I’ve got quite a few of them going round and asking questions, one of them should come up with something soon enough.’

‘It needs to be today.’

‘Then I suggest that you help matters by going to see Senator Pollo after you’ve met with your mate from the Cohort. He may know something about him.’

Magnus muttered his agreement as the Viminal Gate came into sight.

‘It’s just up here on the left before the junction with the Lampmakers’ Street,’ Servius informed him. ‘We should get on to the right-hand side of the road.’

They crossed at the next set of raised stepping-stones, designed to keep pedestrians’ feet free from ordure but also to allow the passage of wheeled vehicles, and disappeared into the throng of people opening shops, buying bread, firing up braziers, visiting patrons, clearing drowsy beggars from doorways. Pushing through the crowd, Servius led Magnus to a tavern with an outside bar.

‘Two cups of hot wine,’ he ordered, placing a small-denomination coin on the wooden counter.

Once they had been served, Servius turned and nodded to a large two-storey, brick-built house. ‘That’s the Albanians’ place. As you can see it has no windows opening on to the street, no shops in its facade, it’s just a blank wall and a door.’

Magnus looked at the two huge, bearded doormen in eastern garb, armed with cudgels and knives, guarding the entrance. ‘Is that door the only way in and out?’

‘Fortunately not.’ Servius pointed to a small street that led off from the Via Patricius two houses up from the Albanians’ establishment. ‘That’s the Lamp-makers’ Street. There’s an alley that runs from it along the rear of all the buildings opposite; I sent Cassandros to have a look at it last night after the swap; he says that the wall is only ten feet high and we could easily scale it and get up onto the roof.’

‘He’s making up for his mistake.’

‘I gave him a dangerous assignment and he understood why.’

Magnus grunted approvingly. ‘We need to teach the randy sod a lesson; but that can wait. Do they keep a guard in the alley?’

‘Cassandros said that there was no one there last night, we’ll walk past in a moment and see if there’s one during the day.’

‘So, we get in and out over the roof, but we’ve still got those two brutes on the door to deal with. When they hear noise inside at least one of them will come in – that’ll make it easier.’ Magnus took a sip of his wine. ‘So if we have a group of our lads close by they could deal with the remaining one and then take the door; that sounds like a job for me and Marius, he’s not much good at shinning up walls in a hurry with just one hand.’

‘Yes, but you’d have to be quick to get the door before it’s bolted again on the inside.’

‘Unless we can make them think that some of their own are in danger out here in the street and are running for safety.’

‘How?’

‘I met an easterner last night and he owes me a favour. His name’s Tigran, he lives in the shanty town on the Via Salaria; find him and see if he speaks Albanian or knows anyone who does.’ A well-dressed figure striding up the street with two bodyguards and a woman in a hooded, dark-brown cloak caught Magnus’ attention. ‘Well, well, our friend Sempronius is paying the whore-boys a visit; I wouldn’t have thought that that was his sort of thing.’

‘He’s probably just come to check that the exchange went all right last night. But what’s really interesting is who he’s got with him; I think I recognise that cloak.’

Sempronius’ party approached the two doormen, one of whom immediately knocked rhythmically on the door; it opened and the doormen stepped aside to allow Sempronius in. As the woman followed him in she pulled down her hood.

Magnus’ eyes widened. ‘Minerva’s wrinkled arse, that’s the new girl, Aquilina! I thought that there was something wrong about her when she offered to let me have her for nothing; nobody does something for nothing.’

Servius downed the last of his wine. ‘Evidently someone else paid her. It seems that Sempronius has put a little spy in our midst.’

Magnus slapped his counsellor on the shoulder. ‘I’d say that was a piece of good fortune. I think that’s just solved my last problem.’

‘You’re late!’

Magnus chuckled looking down at the shadow cast by the seventy-feet-high Egyptian obelisk on the Campus Martius; it was a couple of inches short of the third-hour line. ‘I didn’t think that anyone had the brains to read the sundial since I left the Urban Cohort, Aelianus.’

‘True enough, mate, I’m probably the only one who can, which is why they made me quartermaster,’ Aelianus replied, grasping Magnus’ proffered forearm.

‘A moment of madness on their part but one that’s proved extremely lucrative for us, eh, my friend?’

Aelianus’ florid, round face creased into a gap-toothed grin and he passed his hand through his thinning copper-coloured hair. ‘And how are we going to exploit their moment of madness this time?’

Magnus put an arm around the Aelianus’ shoulders and led him away from the tourists admiring the hundred-feet-long, curved hour-lines emanating from the base of the obelisk sundial – set up by Augustus a generation before – and on towards the first emperor’s mausoleum on the bank of the Tiber, as it curved back northwards after a brief foray east. ‘Get me twenty Urban Cohort uniforms, minus the armour and shields.’

‘What for?’

‘To pay a visit to an establishment that has caused me some grief. Oh, and I’ll also need you to set fire to your depot.’

Aelianus raised his eyebrows. ‘Just like that?’

‘Yes, my friend, just like that.’

‘And what’s in it for me?’

‘Half of what we find in the place, but with a guarantee of at least two hundred and twenty-five denarii.’

Aelianus whistled softly. ‘A year’s pay for a common legionary. Well, the tunics, belts, boots and cloaks will be no problem – I can have those for you by this evening. The helmets, swords and scabbards are slightly harder because I’ll have to wait until all my staff have left for the day – but I could bring them round to you personally by the third hour of the night. When do you plan to do this thing?’

‘The day after tomorrow, an hour before dawn when there shouldn’t be any clients in the house; so tonight will be fine, you can bring it all then.’

‘Good. But as to the fire, that’s a different matter: I need to think that through very carefully.’

‘Well, don’t take too long about it, my friend. I need that warehouse doing its best imitation of a beacon an hour before dawn in two days’ time.’

‘Oh it will be, Magnus, don’t you worry.’

‘That’s why I’m paying you so well, Aelianus, to take away my worries.’

The ginger quartermaster grinned again. ‘If only you had more worries, I’d be a very wealthy man. I’ll see you later with the gear; can you send a few of your lads to escort me?’

‘Sure, they’ll be at your depot by the second hour of the night.’

‘Thanks, mate,’ Aelianus said, turning to leave.

‘Before you go, Aelianus,’ Magnus said, stopping him, ‘there’s one more thing that I’ll need you to do when you come over tonight.’

‘It’s included in the price, I suppose?’

‘Yes and it’s not negotiable.’

‘Go on.’

‘I need you to fuck one of my girls.’

Aelianus sighed melodramatically and shook his head slowly. ‘Magnus, you’re a hard taskmaster.’

The forum romanum was packed – three treason trials were being conducted simultaneously, part of a recent upsurge in the legal hounding of enemies of the emperor or the rivals of his praetorian prefect. To Magnus, how the equestrian or senatorial classes treated each other meant nothing, provided it did not affect the daily running of the city’s institutions that were close to his heart: the games and the grain dole.