0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

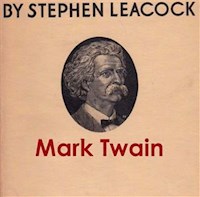

This is a most interesting biography of Mark Twain by Canada's own famous classic "funny man" Stephen Leacock. The sketch of Mark Twain is an amazing portrait, virile, graphic, loving, and of course humorous. The perfect combination of Leacock and Twain was a happy choice as both men were the geniuses of humor writing of their era...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Mark Twain

by Stephen Leacock

First published in 1932

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Mark Twain

by Stephen Leacock

MARK TWAIN

A photograph taken in 1870

ICHILDHOOD AND YOUTH—MARK TWAIN AS TOM SAWYER—1835-1857

The name of Mark Twain stands for American humour. More than that of any other writer, more than all names together, his name conveys the idea of American humour. For two generations his reputation and his fame have been carried all over the world with this connotation. He has become, as it were, an idea, a sort of abstraction, comparable to John Bull who represents England, or Sherlock Holmes who signifies an inexorable chain of logic.

The name, as all the world knows, is only a pen-name, selected after the conceited fashion of the day and taken from the river-calls of the Mississippi pilots. But its apt and easy sound rapidly obliterated the clumsy name of the writer who wore it. Samuel Langhorne Clemens died to the world, or rather, never lived for it. ‘Mark Twain’ became a household word for millions and came to signify not merely a particular person but an idea. Thus, side by side with Mr. Clemens, who is dead, there grew an imaginary person, Mark Twain, who became a legend and is living still.

American humour rose on the horizon of the nineteenth century as one of the undisputed national products of the new republic. Of American literature there was much doubt in Europe; of American honesty, much more; of American manners, more still. But American humour found a place alongside of German philosophy, Italian music, French wine, and British banking. No one denied its peculiar excellence and its distinctive national stamp.

Now Mark Twain did not create American humour nor the peculiar philosophy of life on which it rests. Before him were the Major Dowlings and the Sam Slicks, and in his own day the Petroleum Nasebys and the Orpheus C. Kerrs and others now resting as quietly as they do. But in the retrospect of retreating years nearly all the work of these sinks into insignificant dreariness or into a mere juggle of words, cheap and ephemeral. The name of only one contemporary, Artemus Ward, may be set in a higher light. Yet all that Ward ever wrote in words, as apart from his quaint and pathetic personality, is but a fragment. If Mark Twain did not create American humour, he at least took it over and made something of it. He did for it what Shakespeare did for the English drama, and what Milton did for Hell. He ‘put it on the map.’ He shaped it into a form of thought, a way of looking at things, and hence a mode or kind of literature.

Not that Mark Twain did all this consciously. A deliberate humorist, seeking his effect, is as tiresome as a conscientious clown working by the week. His humour lay in his point of view, his angle of vision and the truth with which he conveyed it. This often enabled people quite suddenly to see things as they are, and not as they had supposed them to be—a process which creates the peculiar sense of personal triumph which we call humour. The savage shout of exultation modified down to our gurgling laugh greets the overthrow of the thing as it was. Mark Twain achieved this effect not by trying to be funny, but by trying to tell the truth. No one really knew what the German Kaiser was like till Mark Twain dined with him. No one really saw the painted works of the old masters till Mark Twain took a look at them. The absurd multiplicity of the saints was never appreciated till Mark Twain counted them by the gross. The futility of making Egyptian mummies was never realized till he measured them by the cord as firewood. People who had tried in vain to rise to the dummy figures and the sentimental unreality of Tennyson’s Idylls of the King got set straight on chivalry and all its works when they read The Connecticut Yankee at King Arthur’s Court. ‘The boys went grailing,’ says the Yankee, in reference to the pursuit of the Holy Grail by the Knights of the Round Table. ‘The boys went grailing.’ Why not?

Readers who had tried in vain to feel impressed and reverent over Tennyson’s impossible creations felt an infinite relief in seeing them reduced to this familiar footing. Thus in a score of books and in a thousand of anecdotes and phrases there was conveyed to the world something and somebody which it knew as Mark Twain.

All the rest of the man, the other aspects of his mind and personality, was left out of count. The flaming enthusiasms, the fierce elemental passion against tyranny, against monarchy, against hell, against the God of the Bible—all this was, and is, either unknown or forgotten. It has to be. The composite picture, filled in line by line, would leave a new person to be called Samuel L. Clemens. The ‘Mark Twain’ of the legend would crumble into dust.

In any case, Mark Twain only half-expressed himself. Of the things nearest to his mind he spoke but low or spoke not at all. He would have liked to curse England for the Boer War, to curse America for the Philippine conquest, to curse the Roman Catholic Church for its past, and the Czar of Russia for his present. Instinct told him that had he done so, the Mark Twain legend that had filled the world would pass away. The kindly humorist, with a corn-cob pipe would also be a rebel, an atheist, an anti-clerical.

So it was that Mark Twain’s nearest and dearest thoughts were spoken only in a murmur, and the world laughed, thinking this some new absurdity; or were left unspoken, and the world never knew; or were published after he was dead, when no one could catch him. The kindly conspiracy was played out to the end.

It is better that it should be so. It leaves the legendary Mark Twain and his work and his humour as one of the great things of nineteenth-century America.

American he certainly was. He had the advantage, or disadvantage, of being brought up solely in his own country, remote from its coasts, with no contact with the outside world, in the days when America was still America. He lived, and died, before the motion picture had flickered the whole world with similarity, and before rapid transport had enabled every country to live on the tourists of all the others. His childhood was spent in an isolation from the outside world now beyond all conception. Nor was the isolation much relieved by mental contact. Like Shakespeare and Dickens, young Sam Clemens had little school and no college. He thus acquired that peculiar sharpness of mind which comes from not going to school, and that power of independent thought obtained by not entering college. It was this youthful setting which enabled him to become what he was.

Here are some of the essential facts about his early life which need to be mentioned even in a biography.

Samuel Langhorne Clemens was born on the thirtieth of November in 1835 in a frontier settlement which he himself called the ‘almost invisible village of Florida, Monroe County, Missouri.’ His father and mother were people as impoverished and as undistinguished as one could wish. Both came of plain pioneer stock, the father originally from Virginia, the mother from Kentucky. Mark Twain’s father, John Clemens, seems to have been a kindly but shiftless person, succeeding at nothing, but dreaming always of a wonderful future. At intervals in an impoverished youth he had picked up an education and for a time attended a frontier law school. But he turned his hand to store-keeping, to house-building, to anything; and his mind to dreaming. He and his wife Jane went and settled in the mountain wilderness of East Tennessee. The older brothers and sisters of the family, ‘the first crop of children,’ were born there. Then John Clemens, with the restlessness of the frontiersman, moved from one habitat to another, and presently passed on to the new State of Missouri just beginning its existence. But he had meantime managed to raise four hundred dollars and with it to buy a vast tract of land, of about a hundred thousand acres. For the rest of his life the elder Clemens was inspired by visions of his Tennessee land and what it would mean for the future of his descendants. These dreams he passed on to his descendants as their chief legacy.

The Tennessee land contained great forests of yellow pine, beds of oil, deposits of coal and iron and copper, an El Dorado of wealth as we see it now. But in those days the timber was unsaleable for lack of transport, coal was unusable, and petroleum a mere curiosity of the marshes. Yet Clemens managed, with a wrench, to pay his five dollars a year in taxes, and dreamed of wealth to come. After his death the land was muddled away and parted with for next to nothing, till the last ten thousand acres were sold in 1894 for two hundred dollars. But the inspiration of the Tennessee land served as the background of The Gilded Age and helped to fashion the cheery optimism of Colonel Sellers; converted into literature and the drama it earned a fortune.