6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

The long-awaited reissuing of a classic series begins with Matt Helm's first adventure: Death of a Citizen. Matt Helm, one-time special agent for the American government during the Second World War, has left behind his violent past to raise a family in Santa Fe, New Mexico. When a former colleague turns rogue and kidnaps his daughter, Helm is forced to return to his former life as a deadly and relentless assassin.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Contents

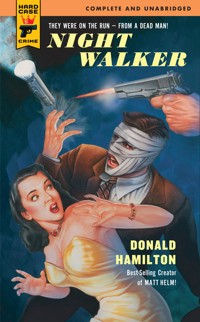

Cover

Also by Donald Hamilton

Title Page

Copyright

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

About the Author

Coming Soon from Titan Books

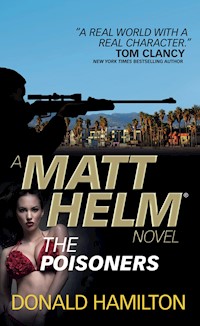

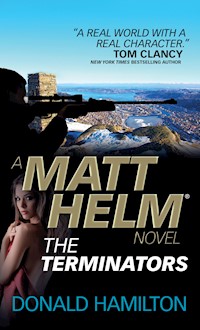

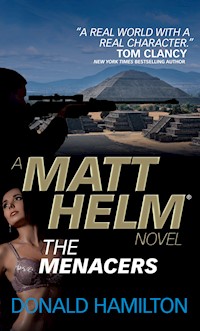

Also Available from Titan Books

Available from Donald Hamilton and Titan Books

The Wrecking Crew

The Removers (April 2013)

The Silencers (June 2013)

Murderers’ Row (August 2013)

The Ambushers (October 2013)

The Shadowers (December 2013)

The Ravagers (February 2014)

Death of a Citizen

Print edition ISBN: 9780857683342

E-book edition ISBN: 9780857686237

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: February 2013

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © 1960, 2013 by Donald Hamilton. All rights reserved.

Matt Helm® is the registered trademark of Integute AB.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

Did you enjoy this book? We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at [email protected] or write to us at Reader Feedback at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

DEATH OF A CITIZEN

1

I was taking a Martini across the room to my wife, who was still chatting with our host, Amos Darrel, the physicist, when the front door of the house opened and a man came in to join the party. He meant nothing to me— but with him was the girl we’d called Tina during the war.

I hadn’t seen her for fifteen years, or thought about her for ten, except once in a great while when that time would come back to me like a hazy and violent dream, and I’d wonder how many of those I’d known and worked with had survived it, and what had happened to them afterwards. I’d also wonder, idly, the way you do, if I’d even recognize the girl, should I meet her again.

After all, that particular job had taken only a week. We’d made our touch right on schedule, earning a commendation from Mac, who wasn’t in the habit of passing them around like business cards—but it had been a tough assignment, and Mac knew it. He’d given us a week to rest up in London, afterwards, and we’d spent it together. That made a total of two weeks, fifteen years ago. I hadn’t known her previously, and I’d never seen her again, until now. If anyone had asked me to guess, I’d have said she was still over in Europe, or just about anywhere in the world except here in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Nevertheless, I didn’t have a moment of doubt. She was taller and older, better looking and much better dressed, than the fierce, bloodthirsty, shabby little waif I remembered. There was no longer the gauntness of hunger in her face or the brightness of hate in her eyes, and she probably no longer concealed a paratrooper’s knife somewhere in her underwear. She looked as if she’d forgotten how to handle a machine pistol; she looked as if she wouldn’t recognize a grenade if she saw one. She certainly no longer wore a capsule of poison taped to the nape of her neck, hidden by her hair. I was sure of this, because her hair was quite short now.

But it was Tina, all right—expensive furs, cocktail dress, and hairdo notwithstanding. She looked at me for a moment without expression, across that room of chattering people, and I couldn’t tell if she recognized me or not. After all, I’d changed a little, too. There was more meat on my bones and less hair on my head after fifteen years. There were the other changes that must have left visible traces for her to see; the wife and three kids, the four-bedroom house with the studio out back and the mortgage half paid up, the comfortable bank account and the sensible insurance program. There was Beth’s shiny Buick station wagon in the driveway outside, and my beatup old Chevy pickup in the garage back home. And on the wall back home were my hunting rifle and shotgun, unfired since the war.

I was an ardent fisherman these days—fish don’t bleed much—but at the back of a desk drawer, kept locked so the kids couldn’t get at it if they should get into the studio against orders, was a gun this girl would remember, the little worn Colt Woodsman with the short barrel, and it was still loaded. And in my pants was the folding knife of Solingen steel that she’d recognize because she’d been present when I’d taken it from a dead man to replace the knife that he’d broken, dying. I still carried that, and sometimes I’d hold it in my hand—closed, of course—in my pocket as I walked home from a movie with my wife, and I’d walk straight at the groups of tough, dark kids that cluttered up the sidewalks of this old southwestern town at night, and they’d move aside to let us pass.

“Don’t look so belligerent, darling,” Beth would say. “Anybody’d think you were trying to pick a fight with those Spanish-American boys.” She’d laugh and press my arm, knowing that her husband was a quiet literary individual who wouldn’t hurt a fly even if he did write stories bursting with violence and dripping with gore. “How do you ever think of these things?” she’d ask, wide-eyed, after reading a particularly gruesome passage about Comanche massacre or Apache torture, generally taken pretty straight from the sourcebooks, but sometimes embellished with some wartime experience of my own, set back a hundred years in time. “I declare, sometimes you frighten me, dear,” my wife would say, and laugh, not frightened at all. “Matt is really quite harmless in spite of the dreadful things he put in his books,” she’d assure our friends happily. “He just has a morbid imagination, I guess, Why, he used to hunt before the war, before I knew him, but he’s even given that up, because he hates to kill anything except on paper…”

* * *

I’d stopped in the middle of the room. For a moment, all the cocktail-party sounds had faded completely from my consciousness. I was looking at Tina. There was nothing in the world except the two of us, and I was back in a time when our world had been young and savage and alive, instead of being old and civilized and dead. For a moment it was as if I, myself, had been dead for fifteen years, and somebody had opened the lid of the coffin and let in light and air.

Then I drew a long breath, and the illusion faded. I was a respectable married man once more. I’d just seen a ghost from my bachelor days, and it could make quite an awkward little situation if I didn’t handle it right, which meant acting just as naturally as I could, walking right up to the girl and greeting her like a long-lost friend and wartime comrade, and hauling her over to meet Beth before any awkwardness could develop.

I looked for a place to park the Martinis before starting over there. The man with Tina had removed his wide-brimmed hat. He was a big, blond man in a suede leather sport coat and a checked gingham shirt with one of those braided leather strings around the neck that Western males tend to wear instead of ties. But this man was a visitor—his outfit was too new and shiny, and he didn’t look comfortable in it.

He reached for Tina’s wrap, and as she turned to give it to him her free hand lifted casually and gracefully to brush the short dark hair back from her ear. She wasn’t looking at me now, not even facing my way, and the movement was wholly natural; but I hadn’t quite forgotten those grim months of training before they sent me out, and I knew the gesture was meant for me. I was seeing again the sign we’d had that meant: I’ll get in touch with you later. Stand by.

It was a chilling thing. I’d almost broken the basic rule that had been drilled into all of us, never to recognize anybody anywhere. It hadn’t occurred to me that we could still be playing by those old rules, that Tina’s presence here, after all these peaceful years, could be due to anything but the wildest and most innocent coincidence. But the old stand-by signal meant business. It meant: Wipe that silly look off your face, Buster, before you louse up the works. You don’t know me, you fool.

It meant that she was working again—perhaps, unlike me, she’d never stopped. It meant that she expected me to help her, after fifteen years.

2

When I reached Amos Darrel, on the other side of the room, he no longer had Beth for company. Instead, he was conversing politely with a young olive-skinned girl with rather long dark hair.

“Your wife deserted me to consult with a matronly female about P.T.A.,” Amos reported. “Her refreshment needs have already been supplied, but I think Miss Herrera will take that extra Martini off your hands.” He made a gesture of introducing us to each other: “Miss Barbara Herrera, Mr. Matthew Helm.” He glanced at me, and asked idly: “Who are those people who just came in, Matt?”

I was passing the extra drink to the girl. My hand was quite steady. I didn’t spill a drop. “I haven’t any idea,” I said.

“Oh, I thought you looked as if you recognized them.” Amos sighed. “Some of Fran’s friends from New York, I suppose… I couldn’t persuade you to sneak back into my study for a game of chess?”

I laughed. “Fran would never forgive me. Besides, you’d have to spot me a queen or a pair of rooks to make a game of it.”

“Oh, you’re not that bad,” he said tolerantly.

“I’m not a mathematical genius, either,” I said.

He was a plump, balding little man with steel-rimmed glasses, behind which his eyes, at the moment, had a vague look that could have been mistaken for stupidity. Actually, in his own field, Amos was one of the least stupid men in the United States—perhaps in the world. This much I knew. Just precisely what his field was, I couldn’t tell you. Even if I knew, I probably wouldn’t be allowed to tell you; but I didn’t know, and I hadn’t the slightest desire to find out. I had enough secrets of my own without worrying about those belonging to Amos Darrel and the Atomic Energy Commission.

All I knew was that the Darrels lived in Santa Fe because Fran Darrel liked it better than Los Alamos, which she considered an artificial little community full of dull scientific people. She much preferred colorful characters like myself, who nibbled at the fringes of art, and Santa Fe is full of them. Amos owned a hot Porsche Carrera coupe in which he commuted daily, summer and winter, the thirty-odd miles up to The Hill, as it’s known locally. The souped-up little sports car didn’t really go with his appearance or what I knew of his character, but then I don’t claim to understand the vagaries of genius, particularly scientific genius.

I did understand him well enough to realize that his present vague, glazed look didn’t indicate stupidity, but simple boredom. Talking to us low-grade morons who don’t know an isotope from a differential equation bores most of those big brains stiff.

Now he yawned, making only a token effort to hide it, and said in a resigned voice: “Well, I’d better go over and greet the newcomers. Excuse me.”

We watched him move away. The girl beside me laughed ruefully. “Somehow, I don’t have the feeling Dr. Darrel found me very entertaining,” she murmured.

“It’s not your fault,” I said. “You’re just too big, that’s all.” She glanced up at me, smiling. “How am I to take that remark?”

“Not personally,” I assured her. “What I mean is, Amos isn’t really interested in anything much bigger than an atom. Oh, he might stretch a point and settle for a molecule now and then, but it would have to be a small molecule.”

She asked innocently, “Oh, are molecules bigger than atoms, Mr. Helm?”

I said, “Molecules are made up of atoms. Now you have the sum total of my information upon that subject, Miss Herrera. Please address any further inquiries to your host.”

“Oh,” she said, ‘I wouldn’t dare!”

I saw that Tina and her suede-jacketed escort were starting to work their way around the room through a barrage of introductions, under the inexorable leadership of Fran Darrel, a small, dry, wisp of a woman with a passion for collecting interesting people. It was a pity, I thought, that Fran would never know what a jewel of interest she had in Tina…

I turned my attention back to the girl. She was quite a pretty girl, wearing a lot of Indian silver and one of the squaw dresses, also called fiesta dresses, the construction of which is a local industry. This one was all white, copiously trimmed with silver braid. As usual, it had a very full, pleated skirt supported by enough stiff petticoats to form a traffic hazard in the Darrels’ crowded living room.

I asked, “Do you live here in Santa Fe, Miss Herrera?”

“No, I’m just here on a visit.” She looked up at me. She had very nice eyes, dark-brown and lustrous, to go with the Spanish name. She said, “Dr. Darrel tells me you’re a writer. What name do you write under, Mr. Helm?”

I suppose I should be used to it by now, but I still can’t help wondering why they do it and what they expect to gain by it. It must seem to them like a subtle social maneuver, a way of skillfully avoiding the dreadful admission that they never heard of a guy named Helm or read any of his works. The only trouble is, I’ve never used a pseudonym in my life—my literary life, that is. There was a time when I answered to the code name of Eric, but that’s another matter.

“I use my own name,” I said, a little stiffly. “Most writers do, Miss Herrera, unless they’re pretty damn prolific, or run into publication conflicts of some kind.”

“Oh,” she said, “I’m sorry.”

It occurred to me that I was being pompous, and I grinned. “I write Western stories, mostly,” I said. “As a matter of fact, I’m leaving in the morning to get some material for a new one.” I glanced at my Martini glass. “Assuming that I’m in condition to drive, that is.”

“Where are you going?”

“Down the Pecos Valley first, and then through Texas to San Antonio,” I said. “After that I’ll head north along one of the old cattle trails to Kansas, taking pictures along the way.”

“You’re a photographer, too?”

She was a cute kid, but she was overdoing the breathless-admiration routine. After all, it wasn’t as if she were talking to Ernest Hemingway.

“Well, I used to be a newspaperman of sorts,” I said “On a small paper you learn to do a little bit of everything That was before the war. The fiction came later.”

“It sounds perfectly fascinating,” the girl said. “But I’m sorry to hear you’re leaving. I kind of hoped, if you had a little time… I mean, there’s something I wanted to ask you, a favor. When Dr. Darrel told me you were a real live author…” She hesitated, and laughed in an embarrassed way, and I knew exactly what was coming. She said, “Well, I’ve been trying to write a little myself, and I do so want to talk to someone who…”

Then, providentially, Fran Darrel was upon us, with Tina and her boy friend, and we had to turn to meet them. Fran was dressed pretty much like my companion, except that her blue fiesta dress, her waist, her arms, and her neck were loaded even more heavily with Indian jewelry. Well, she could afford it. She had money of her own, apart from Amos’ government salary. She introduced the newcomers and the girl, and it was my turn.

“…and here’s somebody I particularly want you to meet, my dear,” Fran said to Tina in her high, breathless voice. “One of our local celebrities, Matt Helm. Matt, this is Madeleine Loris, from New York, and her husband... Hell, I’ve forgotten your first name.”

“Frank,” the blond man said.

Tina had already put out her hand for me to take. Slender and dark and lovely, she was a real pleasure to look at in her sleeveless black dress, and her little black hat that was mostly a scrap of veil, and her long black gloves. I mean, these regional costumes are all very well, but if a woman can look like that, why should she deck herself out to resemble a Navajo squaw?

She extended her hand with a graciousness that made me want to click my heels, bow low, and raise her fingers to my lips—I remembered a time when I had, very briefly, been forced to impersonate a Prussian nobleman. All kinds of memories were coming back, and I could recall very clearly—although it seemed most improbable now—making love to this fashionable and gracious lady in a ditch in the rain, while uniformed men beat the dripping bushes all around us. I could also remember the week in London... Looking into her face, I saw that she, too, was remembering. Then her little finger moved very slightly in my grasp, in a certain way. It was the recognition signal, the one that asserted authority and demanded obedience.

I’d been expecting that. I looked straight into her eyes and made no answering signal, although I remembered the response perfectly. Her eyes narrowed very slightly, and she took back her hand. I turned to shake hands with Frank Loris, if that was his name, which it almost certainly wasn’t.

From his looks, I knew he was going to be a bone-crusher, and he was. At least he tried. When nothing snapped, he, too, tried the little-finger trick. He was a hell of a big man, not quite my height—very few are— but much wider and heavier with the craggy face of the professional muscleman. His nose had been broken many years ago. It could have happened in college football, but somehow I didn’t think so.

You get so you can recognize them. There’s something tight about the mouth and eyes, something wary in the way they stand and move, something contemptuous and condescending that betrays them to one who knows. Even Tina, bathed and shampooed and perfumed, girdled and nyloned, had it. I could see that now. I’d had it once myself. I’d thought I’d lost it. Now I wasn’t so certain.

I looked at the big man, and, oddly enough, we hated each other on sight. I was a happily married man without a thought for any woman but my wife. And he was a professional doing a job—whatever it might be—with an assigned partner. But he would have been briefed before he came here, and he would know that I’d once done a job with the same partner. Whatever his success in extracurricular matters—and from the looks of him he’d be the lad to give it a try—he’d be wondering just how successful I’d been, under similar circumstances, fifteen years ago. And of course, although Tina was nothing to me anymore, I couldn’t help wondering just what her duties as Mrs. Loris involved.

So we hated each other cordially as we shook hands and spoke the usual meaningless words, and I let him grind away at my knuckles and signal frantically, giving no sign that I felt a thing, until the handclasp had lasted long enough to satisfy the proprieties and he had to let me go. To hell with him. And to hell with her. And to hell with Mac, who’d sent them here after all these years to disinter the memories I’d thought safely buried. That is, if Mac was still running the show, and I thought he would be. It was impossible to think of the organization in the hands of anyone else, and who’d want the job?

3

The last time I saw Mac, he was sitting behind a desk in a shabby little office in Washington.

“Here’s your war record,” he said as I came up to the desk. He shoved some papers towards me. “Study it carefully. Here are some additional notes on people and places you’re supposed to have known. Memorize and destroy. And here are the ribbons you’re entitled to wear, should you ever be called back into uniform.”

I looked at them and grinned. “What, no Purple Heart?” I’d just spent three months in various hospitals.

He didn’t smile. “Don’t take these discharge papers too seriously, Eric. You’re out of the Army, to be sure, but don’t let it go to your head.”

“Meaning what, sir?”

“Meaning that there are going to be a lot of chaps”— like all of us, he’d picked up some British turns of speech overseas—“a lot of chaps impressing a lot of susceptible maidens with what brave, misunderstood fellows they were throughout the war, prevented by security from disclosing their heroic exploits to the world. There are also going to be a lot of hair-raising, revealing, and probably quite lucrative memoirs written.” Mac looked up at me, as I stood before him. I had trouble seeing his face clearly, with that bright window behind him, but I could see his eyes. They were gray and cold. “I’m telling you this because your peacetime record shows certain literary tendencies. There’ll be no such memoirs from this outfit. What we were, never was. What we did, never happened. Keep that in mind, Captain Helm.”

His use of my military title and real name marked the end of a part of my life. I was outside now.

I said, “I had no intention of writing anything of the kind, sir.”

“Perhaps not. But you’re to be married soon, I understand, to an attractive young lady you met at a local hospital. Congratulations. But remember what you were taught, Captain Helm. You do not confide in anyone, no matter how close to you. You do not even hint, if the question of wartime service is raised, that there are tales you could tell if you were only at liberty to do so. No matter what the stakes, Captain Helm, no matter what the cost to your pride or reputation or family life, no matter how trustworthy the person involved, you reveal nothing, not even that there’s something to reveal.” He gestured towards the papers on the desk. “Your cover isn’t perfect, of course. No cover is. You may be caught in an inconsistency. You may even meet someone with whom you’re supposed to have been closely associated during some part of the war, who, never having heard of you, calls you a liar and perhaps worse. We’ve done all we can to protect you against such a contingency, for our sakes as well as yours, but there’s always the chance of a slip. If it happens, you’ll stick to your story, no matter how awkward the situation becomes. You’ll lie calmly and keep on lying. To everyone, even your wife. Don’t tell her that you could explain everything if only you were free to speak. Don’t ask her to trust you because things aren’t what they seem. Just look her straight in the eye and lie.”

“I understand,” I said. “May I ask a question?”

“Yes.”

“No disrespect intended, sir, but how are you going to enforce all that, now?”

I thought I saw him smile faintly, but that wasn’t likely. He wasn’t a smiling man. He said, “You’ve been discharged from the Army, Captain Helm. You’ve not been discharged from us. How can we give you a discharge, when we don’t exist?”

And that was all of it, except that as I started for the door with my papers under my arm he called me back.

I turned snappily. “Yes, sir.”

“You’re a good man, Eric. One of my best. Good luck.”

It was something, from Mac, and it pleased me, but as I went out and, from old habit, walked a couple of blocks away from the place, before taking a cab to where Beth was waiting, I knew that he need have no fear of my confiding in her against orders. I’d have told her the truth if it had been allowed, of course, to be honest with her; but my bride-to-be was a gentle and sensitive New England girl, and I wasn’t unhappy to be relieved, by authority, of the necessity of telling her I’d been a good man in that line of business.