15,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

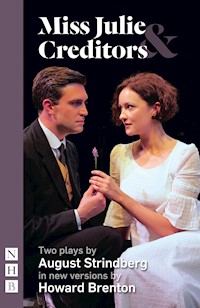

August Strindberg's classic portrayals of secrets and lies, seduction and power – both written in the summer of 1888 – in brilliant new versions by Howard Brenton. Miss Julie begins as a flirtatious game between the daughter of a wealthy landowner and her father's manservant, and gradually descends, over the course of a long and sultry Midsummer's Eve, into a savage fight for survival. In Creditors, young artist Adolf is deeply in love with his new wife Tekla – but a chance meeting with a suave stranger shakes his devotion to the core. Passionate, dangerously funny, and enduringly perceptive, Strindberg considered this wickedly enjoyable black comedy his masterpiece. Both plays premiered in co-productions between Jermyn Street Theatre, London, and Theatre by the Lake, Keswick, directed by Jermyn Street's Artistic Director Tom Littler. 'Riveting... as real and sensational now as ever and as socially and politically pertinent' - Guardian on Miss Julie 'Superlative… an unexpected treat of the highest order' - Evening Standard (Best Productions of 2017) on Miss Julie

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

August Strindberg

MISS JULIE

and

CREDITORS

in new versions by Howard Brenton

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Original Production

The Strindberg Project

Characters

Miss Julie

Creditors

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

Miss Julie and Creditors were performed in repertory at Jermyn Street Theatre, London, and Theatre by the Lake from 22 March – 1 June, 2019. The cast was as follows:

MISS JULIE

Premiered at Theatre by the Lake, Keswick on 1 July, 2017. Revived at Theatre by the Lake, Keswick on 1 April, 2019 with the following cast:

MISS JULIE

Charlotte Hamblin

KRISTIN

Dorothea Myer-Bennett

JEAN

James Sheldon

In the 2017 premiere, the role of Kristin was played by Izabella Urbanowicz.

CREDITORS

Premiered at Theatre by the Lake, Keswick on 22 March, 2019 with the following cast:

TEKLA

Dorothea Myer-Bennett

ADOLF

James Sheldon

GUSTAF

David Sturzaker

Director

Tom Littler

Designer

Louie Whitemore

Lighting Designer

Johanna Town

Sound Designer and Composer

Max Pappenheim

Associate Director

Gabriella Bird

Costume Supervisor

Claire Nicolas

Production Manager at TBTL

Philip Geller

Production Manager at JST

Will Herman

Stage Manager

Lisa Cochrane

Production Co-ordinator for TBTL

Mary Elliott

Technical Manager at TBTL

Andrew Lindsay

The Strindberg Project

Lost with the trolls

The director Tom Littler and I have become obsessed with the theatre of August Strindberg. We feel affection and at times repulsion toward him – his drama is both enlightening and disturbing; it has a mystery and depth we suspect we will never fully understand. We may be quite lost.

It is visceral writing, without easy messages, deeply human but often irrational. He is the first great modernist playwright, yet very close to the Greeks, particularly Euripides, in his iconoclasm towards his time and his twisty, bloody-minded plots. A bitter humour flashes as his characters flail about, locked in a tragic endgame they cannot escape.

He was a troubled and troubling genius. He had extreme love-and-hate relationships with just about everything and everyone – his country, his wives, his contemporaries. It is an understatement to say he was ‘ideologically unstable’ – at times he was an atheist, an occultist, a socialist, an elitist, a reactionary, a progressive, a mystic, a passionate advocate for, then a savage critic of, feminism. He would stray into very dark areas, then pull back and reclaim some kind of balance. His work was frequently censored and banned – he was prosecuted for blasphemy and denounced as one of the most dangerous men alive. And yet there are many accounts that he was a shy, beautiful and very sexy man.

That mad summer

Miss Julie and Creditors were written back to back in a blaze of creativity in the summer of 1888.

After the failure of his play The Father, Strindberg, his wife of ten years standing, Siri von Essen, and their three young children moved to the small fishing village of Taarbæk. They were all but broke. Strindberg wrote a book at lightning speed, in French, in the forlorn hope of selling it quickly in Paris (when eventually published, the book, A Madman’s Defence, caused a sensation). But they were in dire straits.

Then it seemed that a magical world had intervened. A strange old woman, who the children thought was a witch, knocked on their door. On behalf of ‘the Countess Frankenau’ she invited them to stay, for virtually nothing, at the Countess’s castle, Skovlyst, which means ‘Delight of the Forest’. In the twilight a ramshackle, old-fashioned carriage collected the family, driven by a handsome servant. The Strindbergs were entranced.

But the summer became a nightmare. The ‘castle’ was a vast, dilapidated old house, many of the rooms derelict; those offered to the Strindbergs were squalid and filthy. The Countess was not really a Countess and she was mercurially unstable. She was besieged by lawsuits for debt and complaints from local people about ‘goings-on’. The servant, Ludvig Hansen, was not a servant; he was the Countess’s secret lover. He was also a thief and a psychopathic conman. Strindberg was fooled by his fantastical claims to ‘gypsy powers’ and spent hours carousing with him. The children loved the wild gardens and the old house, but Siri was increasingly fearful. Strindberg clung onto his delusions about the Skovlyst magical world as their marriage imploded. The summer ended disastrously. Hansen turned on Strindberg, accusing him of seducing his underaged sister. It was a con and Strindberg refused to pay him off. A court dismissed the charge, but for Siri it was the last straw.

Yet, as the summer dream deteriorated into chaos, Strindberg was somehow able to write his two great naturalistic masterpieces. There is something alchemical about his writing. He could turn the sludgy elements of disastrous personal experience into theatrical gold.

Ibsen vs Strindberg?

‘Strindberg Strindberg Strindberg… the greatest of them all. Ibsen can sit serenely in his Doll’s House, while Strindberg is battling with his heaven and his hell.’

Sean O’Casey

Strindberg never met his Norwegian contemporary, Henrik Ibsen, but their rivalry was notorious. They were hyper-alert to whose reputation was on the rise or the fall, greeting each other’s latest play with disdain and even abuse (Strindberg called Ibsen’s A Doll’s House ‘swinery’). Ibsen spent many years out of Norway, living in hotels. He travelled with favourite items of furniture, including a large portrait of Strindberg which he hung above his writing desk – he said ‘I cannot work without that madman’s eyes staring down at me.’ His wife once came in when he had just finished a scene to find him shaking his fist at the portrait and shouting ‘See! See, you bastard!’

It was a kind of inverted admiration – inflamed, I suspect, by fear that the other was the better writer! And they did directly influence each other. It may seem a bizarre comparison if you know the plays but Strindberg’s The Father was meant as a direct riposte to A Doll’s House. Hedda Gabler is obviously Ibsen’s most Strindbergian play. They were both great masters, and the force of their work still inspires playwrights: Ibsen’s social dramas, like An Enemy of the People, with its cover-up of a public scandal, and John Gabriel Borkmann, with its disgraced banker anti-hero, informed Arthur Miller and our British ‘state of the nation’ plays. Strindberg’s modernism, once so wildly experimental, echoes on in O’Neill, Beckett, Tennessee Williams, Albee, Pinter, and Caryl Churchill’s later work.

Reputations come and go, of course. But at the moment Ibsen is widely seen as second only to Shakespeare. The architecture of his work is formidable, a consistently developing span, a theatrical cathedral of plays from his poetic folk tale Peer Gynt, through his naturalistic prose dramas to the late, increasingly imagist and poetic work, and his strange, demented last play, When We Dead Awaken. But, with the possible exception of that play and some early verse dramas that are never performed, there is not a dud.

By contrast Strindberg’s similarly vast output is a mess. He would develop a sequence of work then detonate it, fall silent then reinvent his theatre, only to smash it again. His collected plays are no cathedral, more a series of magnificent rooms surviving amidst ruins – which were blown up by their creator. He can be slapdash, his plotting is often chaotic (in Creditors ‘who caught what ferry, when’ has driven directors – and adapters – to distraction). It is important to realise he was not only a playwright: he wrote novels, autobiographies, polemics – among them a radical manifesto for the rights of women, which infuriated the conservative Queen of Sweden, and a profound plea for the rights of children – a bizarre ‘occult diary’, history books, children’s books. He was also a considerable landscape painter and his experiments with multi-exposure photography anticipated Man Ray and the surrealists. For a while he practised alchemy.

Artists are often ecstatics, and Ibsen and Strindberg were no exceptions. To be an ecstatic is, at times, to have searing insights, but it is a state that can be all-consuming and a curse. Both tried to write a play to dramatise the experience, perhaps to escape it – Ibsen with his first critical success, Brand, about a rogue, all-or-nothing preacher, and Strindberg with his late, difficult, hallucinatory trilogy To Damascus, a Dantesque quest for redemption through unreliable memories. And, like so many ecstatics in the arts before and after them, they were both alcoholics.

By the time he was in his late thirties, Ibsen was a failure. His early plays were reviled; he wore himself out trying to run a second-rate theatre in Christiania, attacked by the press and criticised by a petty-minded board which eventually fired him. Broke, struggling to support a young family, for a while drink overwhelmed him. He would be found unconscious in the gutter outside the family’s shabby rooms above a chemist. But, with the unstinting support of his wife Suzannah, he recovered, scraped enough money together to leave Norway and reinvented himself as the Ibsen we know. He was one of world literature’s great late-developers – nearly all the plays we celebrate were written after he was forty. Michael Meyer, Ibsen’s biographer and translator, thought the memory of the alcoholic episode haunted Ibsen for the rest of his life. He buttoned himself down, adopted a rigid discipline in everyday life, dependent on his wife as an overseer. He shored himself up and suppressed a chaos that blazed within, the secret source of his imagination.

Far from suppressing his demons, Strindberg gave them full voice, amplifying them in his work. But in February 1896, fuelled by an addiction to absinthe, they overcame him – he broke down and suffered a mental and spiritual crisis. Deeply disturbed, plagued by hallucinations, he holed up in various hotel rooms in Paris, most famously in the Hotel Orfila in the Rue d’Assas. This ‘Inferno period’ is key to Strindberg’s development. To try to understand it and as part of our project, I wrote a play, The Blinding Light, which Tom directed at Jermyn Street Theatre in 2017.

Descend to ascend

Strindberg at last had great success in Paris. A revival of Miss Julie in 1893 was a hit and, in 1895, The Father had been rapturously received. But now he abandoned playwriting. He announced he was not a writer but a true ‘natural scientist’, an alchemist. His hands burnt by chemicals, he attempted to make gold.

He chronicled the experience in his novel Inferno. Like so much of his autobiographical writing, it is unreliable; truth in Strindberg is, shall we say, a moveable reality – in my play he says ‘The bright memories are always true.’ As his sympathetic biographer Sue Prideaux points out, he saw himself as a vivisector of personal experience. Self-dramatisation was never far away. Under the autobiographical hysteria, there is a deep hilarity about life’s extremes – it certainly surfaces in Creditors.

But it is beyond doubt that in the Hotel Orfila he was in the midst of a psychotic episode, convinced supernatural forces were trying to stop his experiments in alchemy. The Strindberg scholar Michael Robinson told me that, in the 1970s, researching in the Royal Library in Stockholm, he opened a notebook of Strindberg’s never looked at before – the huge archive was then not fully explored. Small strips of card, two inches long, fell out. At their ends they had a yellowy stain. They were for testing for gold.

So, to put it mildly, Strindberg was not in great shape in the Hotel Orfila. ‘The forces’ were trying to gas him through the wall, then beam electricity at him; he feared they would send a woman succubus to drain his blood. When he went out, there were signs with secret messages everywhere, street names, shapes on walls. He was tormented by his alienation from his three children, the continued fallout from his divorce with Siri and the breakdown of his second marriage to Frida Uhl.

But there is another way of looking at what seems a total breakdown. He had taken the realism of plays like The Father, Creditors and Miss Julie, in its day a revolutionary theatre, as far as he could. He had hit a wall. Strindberg wrote and lived off his instincts, his feelings, swinging between extremes; he may be one of the first modernists but he is also one of the last romantics. Instinctively, despite the psychosis and the absinthe, he was trying to destroy then rebuild his view of the world. He was experimenting on himself.

And alchemy was an ideal guide. Like all mystic systems it is a process of steps towards perfection. First everything must be broken down to a stage of ‘putrefaction’. Only then can the ascent to the final stage begin, ‘coagulation’: the transformation of all that is base into incorruptible gold. But – and this greatly appealed to Strindberg – to achieve the chemical process the alchemist must, in parallel, break down his own very being to be able to ascend to a final state of realisation. Alchemy is a moral quest.

Bonkers? But it worked. After four years’ silence Strindberg returned to the theatre with a series of fantastical plays such as A Dream Play and The Ghost Sonata. Were the alchemy and the playwriting actually the same project? Before and after the crisis in Paris he always wanted to make the theatre more real, at first by being true to the minutiae of everyday life – the famous cooking on stage in Miss Julie – then by trying to stage psychological states so vividly you think you are dreaming wide awake. By ‘realist’ or ‘expressionist’ means he wanted audiences to see the world in a new light.

Adapter’s cheek

I know it is a cheek of me to attempt to write versions of these great plays and not only because I don’t know a word of Swedish. I wanted to do something that is impossible – to write the two plays so true to Strindberg that it would seem it was he, not I, who was writing Miss Julie and Creditors in English.

It’s a fashion for playwrights to ‘bring their own worlds’ to classics, which means mucking them about to make them ‘modern and relevant’. This is an age that craves instant, twittered moral messages. Of course, theatre is a night out, not an academic exercise. Strindberg’s plays were written in a different era; it is impossible to stage what his audiences experienced over a hundred years ago. But if you impose your own concerns, update or, oh horror, ‘deconstruct’ the plays, you will choke off Strindberg’s unique voice. Let the classic writers speak, as far as you can, on their terms, not ours. What comes out can amaze.

I didn’t read any other English translations or versions of the plays or look at tapes or YouTube extracts of famous productions. I wanted to be as far as possible uncontaminated, as near as I could be to the source.