Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

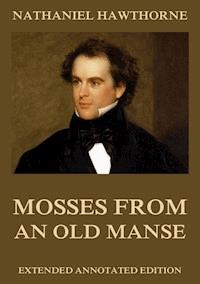

This is the annotated edition including both volumes of the original book, a rare biographical essay on the author, as well as an essay by Edgar Allan Poe on Hawthorne's tale-writing. In 1846 the "Mosses from an Old Manse" was published in New York in two volumes, which contain, on the whole, his best work in short stories, and are prefaced by one of his most delightful essays, "The Old Manse." In some of them, it may be, the allegory is too apparent, but in general they are very deep and searching studies of the heart and conscience. Among the best are " Young Goodman Brown," " Roger Malvin's Burial," " Rappaccini's' Daughter," which is usually placed highest, and " Drowne's Wooden Image." " The Birthmark " and " The Artist of the Beautiful" also rank high in the estimation of critics. "The Celestial Railroad " is a clever satire on modern religion; "The Intelligence Ofiice," "The Procession of Life," and "Earth's Holocaust" are conceits with a burden of symbolic meaning. "The Old Apple-Dealer " is a study of a character with the least possible amount of coloring. " P.'s Correspondence" is mainly interesting, perhaps, for the curious speculation, under the guise of a lunatic's vagaries, on what age might have made of those early poets of the century who died young or in middle life, - especially of what its sobering and conservative tendencies would have done for Byron, Burns, Shelley, and Keats. " The Hall of Fantasy," " A Select Party," and " A Virtuoso's Collection" are ingeniously executed fancies. "Mrs. Bullfrog" is a light, humorous sketch, and " Fire Worship" and " Buds and Bird Voices" are delightful essays.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 821

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Mosses from an Old Manse

Nathaniel Hawthorne

Contents:

Nathaniel Hawthorne – A Biographical Primer

Hawthorne's Tale-Writing

The Old Manse

The Birth-mark

A Select Party

Young Goodman Brown

Rappaccini's Daughter

Mrs. Bullfrog

Fire-Worship

Buds and Bird-Voices

Monsieur du Miroir

The Hall of Fantasy

The Celestial Rail-road

The Procession of Life

Feathertop

The New Adam and Eve

Egotism; or, The Bosom-Serpent *

The Christmas Banquet

Drowne's Wooden Image

The Intelligence Office

Roger Malvin's Burial

P.'s Correspondence

Earth's Holocaust

Passages from a Relinquished Work

At Home

A Flight In The Fog

A Fellow-Traveller

The Village Theatre

Sketches from Memory

The Notch Of The White Mountains

Our Evening Party Among The Mountains

The Canal-Boat

The Old Apple-Dealer

The Artist of the Beautiful

A Virtuoso's Collection

Mosses from an Old Manse, N. Hawthorne

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Germany

ISBN: 9783849640880

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

www.facebook.com/jazzybeeverlag

Nathaniel Hawthorne – A Biographical Primer

By Edward Everett Hale

American novelist: b. Salem, Mass., 4 July 1804; d. Plymouth, N. H., 19 May 1864. The founder of the family in America was William Hathorne (as the name was then spelled), a typical Puritan and a public man of importance. John, his son, was a judge, one of those presiding over the witchcraft trials. Of Joseph in the next generation little is said, but Daniel, next in decent, followed the sea and commanded a privateer in the Revolution, while his son Nathaniel, father of the romancer, was also a sea Captain. This pure New England descent gave a personal character to Hawthorne's presentations of New England life; when he writes of the strictness of the early Puritans, of the forests haunted by Indians, of the magnificence of the provincial days, of men high in the opinion of their towns-people, of the reaching out to far lands and exotic splendors, he is expressing the stored-up experience of his race. His father died when Nathaniel was but four and the little family lived a secluded life with his mother. He was a handsome boy and quite devoted to reading, by an early accident which for a time prevented outdoor games. His first school was with Dr. Worcester, the lexicographer. In 1818 his mother moved to Raymond, Me., where her brother had bought land, and Hawthorne went to Bowdoin College. He entered college at the age of 17 in the same class with Longfellow. In the class above him was Franklin Pierce, afterward 12th President of the United States. On being graduated in 1825 Hawthorne determined upon literature as a profession, but his first efforts were without success. ‘Fanshawe’ was published anonymously in 1828, and shorter tales and sketches were without importance. Little need be said of these earlier years save to note that they were full of reading and observation. In 1836 he edited in Boston the AmericanMagazine for Useful and Entertaining Knowledge, but gained little from it save an introduction to ‘The Token,’ in which his tales first came to be known. Returning to Salem he lived a very secluded life, seeing almost no one (rather a family trait), and devoted to his thoughts and imaginations. He was a strong and powerful man, of excellent health and, though silent, cheerful, and a delightful companion when be chose. But intellectually he was of a separated and individual type, having his own extravagances and powers and submitting to no companionship in influence. In 1837 appeared ‘Twice Told Tales’ in book form: in a preface written afterward Hawthorne says that he was at this time “the obscurest man of letters in America.” Gradually he began to be more widely received. In 1839 he became engaged to Miss Sophia Peabody, but was not married for some years. In 1838 he was appointed to a place in the Boston custom house, but found that he could not easily save time enough for literature and was not very sorry when the change of administration put him out of office. In 1841 was founded the socialistic community at Brook Farm: it seemed to Hawthorne that here was a chance for a union of intellectual and physical work, whereby he might make a suitable home for his future wife. It failed to fulfil his expectations and Hawthorne withdrew from the experiment. In 1842 he was married and moved with his wife to the Old Manse at Concord just above the historic bridge. Here chiefly he wrote the ‘Mosses of an Old Manse’ (1846). In 1845 he published a second series of ‘Twice Told Tales’; in this year also the family moved to Salem, where he had received the appointment of surveyor at the custom house. As before, official work was a hindrance to literature; not till 1849 when he lost his position could he work seriously. He used his new-found leisure in carrying out a theme that had been long in his mind and produced ‘The Scarlet Letter’ in 1850. This, the first of his longer novels, was received with enthusiasm and at once gave him a distinct place in literature. He now moved to Lenox, Mass., where he began on ‘The House of Seven Gables,’ which was published in 1851. He also wrote ‘A Wonder-Book’ here, which in its way has become as famous as his more important work. In December 1851 he moved to West Newton, and shortly to Concord again, this time to the Wayside. At Newton he wrote ‘The Blithedale Romance.’ Having settled himself at Concord in the summer of 1852, his first literary work was to write the life of his college friend, Franklin Pierce, just nominated for the Presidency. This done he turned to ‘Tanglewood Tales,’ a volume not unlike the ‘Wonder-Book.’ In 1853 he was named consul to Liverpool: at first he declined the position, but finally resolved to take this opportunity to see something of Europe. He spent four years in England, and then a year in Italy. As before, he could write nothing while an official, and resigned in 1857 to go to Rome, where he passed the winter, and to Florence, where he received suggestions and ideas which gave him stimulus for literary work. The summer of 1858 he passed at Redcar, in Yorkshire, where he wrote ‘The Marble Faun.’ In June 1860 he sailed for America, where he returned to the Wayside. For a time he did little literary work; in 1863 he published ‘Our Old Home,’ a series of sketches of English life, and planned a new novel, ‘The Dolliver Romance,’ also called ‘Pansie.’ But though he suffered from no disease his vitality seemed relaxed; some unfortunate accidents had a depressing effect, and in the midst of a carriage trip into the White Mountains with his old friend, Franklin Pierce, he died suddenly at Plymouth, N. H., early in the morning, 19 May 1864.

The works of Hawthorne consist of novels, short stories, tales for children, sketches of life and travel and some miscellaneous pieces of a biographical or descriptive character. Besides these there were published after his death extracts from his notebooks. Of his novels ‘The Scarlet Letter’ is a story of old New England; it has a powerful moral idea at bottom, but it is equally strong in its presentation of life and character in the early days of Massachusetts. ‘House of the Seven Gables’ presents New England life of a later date; there is more of careful analysis and presentation of character and more description of life and manners, but less moral intensity. ‘The Blithedale Romance’ is less strong; Hawthorne seems hardly to grasp his subject. It makes the third in what may be called a series of romances presenting the molding currents of New England life: the first showing the factors of religion and sin, the second the forces of hereditary good and evil, and the third giving a picture of intellectual and emotional ferment in a society which had come from very different beginnings. ‘Septimius Felton,’ finished in the main but not published by Hawthorne, is a fantastic story dealing with the idea of immortality. It was put aside by Hawthorne when he began to write ‘The Dolliver Romance,’ of which he completed only the first chapters. ‘Dr. Grimshaw's Secret’ (published in 1882) is also not entirely finished. These three books represent a purpose that Hawthorne never carried out. He had presented New England life, with which the life of himself and his ancestry was so indissolubly connected, in three characteristic phases. He had traced New England history to its source. He now looked back across the ocean to the England he had learned to know, and thought of a tale that should bridge the gulf between the Old World and the New. But the stories are all incomplete and should be read only by the student. The same thing may be said of ‘Fanshawe,’ which was published anonymously early in Hawthorne's life and later withdrawn from circulation. ‘The Marble Faun’ presents to us a conception of the Old World at its oldest point. It is Hawthorne's most elaborate work, and if every one were familiar with the scenes so discursively described, would probably be more generally considered his best. Like the other novels its motive is based on the problem of evil, but we have not precisely atonement nor retribution, as in his first two novels. The story is one of development, a transformation of the soul through the overcoming of evil. The four novels constitute the foundation of Hawthorne's literary fame and character, but the collections of short stories do much to develop and complete the structure. They are of various kinds, as follows: (1) Sketches of current life or of history, as ‘Rills from the Town Pump,’ ‘The Village Uncle,’ ‘Main Street,’ ‘Old News.’ These are chiefly descriptive and have little story; there are about 20 of them. (2) Stories of old New England, as ‘The Gray Champion,’ ‘The Gentle Boy,’ ‘Tales of the Province House.’ These stories are often illustrative of some idea and so might find place in the next set. (3) Stories based upon some idea, as ‘Ethan Brand,’ which presents the idea of the unpardonable sin; ‘The Minister's Black Veil,’ the idea of the separation of each soul from its fellows; ‘Young Goodman Brown,’ the power of doubt in good and evil. These are the most characteristic of Hawthorne's short stories; there are about a dozen of them. (4) Somewhat different are the allegories, as ‘The Great Stone Face,’ ‘Rappacini's Daughter,’ ‘The Great Carbuncle.’ Here the figures are not examples or types, but symbols, although in no story is the allegory consistent. (5) There are also purely fantastic developments of some idea, as ‘The New Adam and Eve,’ ‘The Christmas Banquet,’ ‘The Celestial Railroad.’ These differ from the others in that there is an almost logical development of some fancy, as in case of the first the idea of a perfectly natural pair being suddenly introduced to all the conventionalities of our civilization. There are perhaps 20 of these fantasies. Hawthorne's stories from classical mythology, the ‘Wonder-Book’ and ‘Tanglewood Tales,’ belong to a special class of books, those in which men of genius have retold stories of the past in forms suited to the present. The stories themselves are set in a piece of narrative and description which gives the atmosphere of the time of the writer, and the old legends are turned from stately myths not merely to children's stories, but to romantic fancies. Mr. Pringle in ‘Tanglewood Fireside’ comments on the idea: “Eustace,” he says to the young college student who had been telling the stories to the children, “pray let me advise you never more to meddle with a classical myth. Your imagination is altogether Gothic and will inevitably Gothicize everything that you touch. The effect is like bedaubing a marble statue with paint. This giant, now! How can you have ventured to thrust his huge disproportioned mass among the seemly outlines of Grecian fable?” “I described the giant as he appeared to me,” replied the student, “And, sir, if you would only bring your mind into such a relation to these fables as is necessary in order to remodel them, you would see at once that an old Greek has no more exclusive right to them than a modern Yankee has. They are the common property of the world and of all time” (“Wonder-Book,” p. 135). ‘Grandfather's Chair’ was also written primarily for children and gives narratives of New England history, joined together by a running comment and narrative from Grandfather, whose old chair had come to New England, not in the Mayflower, but with John Winthrop and the first settlers of Boston. ‘Biographical Stories,’ in a somewhat similar framework, tells of the lives of Franklin, Benjamin West and others. It should be noted of these books that Hawthorne's writings for children were always written with as much care and thought as his more serious work. ‘Our Old Home’ was the outcome of that less remembered side of Hawthorne's genius which was a master of the details of circumstance and surroundings. The notebooks give us this also, but the American notebook has also rather a peculiar interest in giving us many of Hawthorne's first ideas which were afterward worked out into stories and sketches.

One element in Hawthorne's intellectual make-up was his interest in the observation of life and his power of description of scenes, manners and character. This is to be seen especially, as has been said, in his notebooks and in ‘Our Old Home,’ and in slightly modified form in the sketches noted above. These studies make up a considerable part of ‘Twice Told Tales’ and ‘Mosses from an Old Manse,’ and represent a side of Hawthorne's genius not always borne in mind. Had this interest been predominant in him we might have had in Hawthorne as great a novelist of our everyday life as James or Howells. In the ‘House of Seven Gables’ the power comes into full play; 100 pages hardly complete the descriptions of the simple occupations of a single uneventful day. In Hawthorne, however, this interest in the life around him was mingled with a great interest in history, as we may see, not only in the stories of old New England noted above, but in the descriptive passages of ‘The Scarlet Letter.’ Still we have not, even here, the special quality for which we know Hawthorne. Many great realists have written historical novels, for the same curiosity that absorbs one in the affairs of everyday may readily absorb one in the recreation of the past. In Hawthorne, however, was another element very different. His imagination often furnished him with conceptions having little connection with the actual circumstances of life. The fanciful developments of an idea noted above (5) have almost no relation to fact: they are “made up out of his own head.” They are fantastic enough, but generally they are developments of some moral idea and a still more ideal development of such conceptions was not uncommon in Hawthorne. ‘Rappacini's Daughter’ is an allegory in which the idea is given a wholly imaginary setting, not resembling anything that Hawthorne had ever known from observation. These two elements sometimes appear in Hawthorne's work separate and distinct just as they did in his life: sometimes he secluded himself in his room, going out only after nightfall; sometimes he wandered through the country observing life and meeting with everybody. But neither of these elements alone produced anything great, probably because for anything great we need the whole man. The true Hawthorne was a combination of these two elements, with various others of personal character, and artistic ability that cannot be specified here. The most obvious combination between these two elements, so far as literature is concerned, between the fact of external life and the idea of inward imagination, is by a symbol. The symbolist sees in everyday facts a presentation of ideas. Hawthorne wrote a number of tales that are practically allegories: ‘The Great Stone Face’ uses facts with which Hawthorne was familiar, persons and scenes that he knew, for the presentation of a conception of the ideal. His novels, too, are full of symbolism. ‘The Scarlet Letter’ itself is a symbol and the rich clothing of Little Pearl, Alice's posies among the Seven Gables, the old musty house itself, are symbols, Zenobia's flower, Hilda's doves. But this is not the highest synthesis of power, as Hawthorne sometimes felt himself, as when he said of ‘The Great Stone Face,’ that the moral was too plain and manifest for a work of art. However much we may delight in symbolism it must be admitted that a symbol that represents an idea only by a fanciful connection will not bear the seriousness of analysis of which a moral idea must be capable. A scarlet letter A has no real connection with adultery, which begins with A and is a scarlet sin only to such as know certain languages and certain metaphors. So Hawthorne aimed at a higher combination of the powers of which he was quite aware, and found it in figures and situations in which great ideas are implicit. In his finest work we have, not the circumstance before the conception or the conception before the circumstance, as in allegory. We have the idea in the fact, as it is in life, the two inseparable. Hester Prynne's life does not merely present to us the idea that the breaking of a social law makes one a stranger to society with its advantages and disadvantages. Hester is the result of her breaking that law. The story of Donatello is not merely a way of conveying the idea that the soul which conquers evil thereby grows strong in being and life. Donatello himself is such a soul growing and developing. We cannot get the idea without the fact, nor the fact without the idea. This is the especial power of Hawthorne, the power of presenting truth implicit in life. Add to this his profound preoccupation with the problem of evil in this world, with its appearance, its disappearance, its metamorphoses, and we have a due to Hawthorne's greatest works. In ‘The Scarlet Letter,’ ‘The House of Seven Gables,’ ‘The Marble Faun,’ ‘Ethan Brand,’ ‘The Gray Champion,’ the ideas cannot be separated from the personalities which express them. It is this which constitutes Hawthorne's lasting power in literature. His observation is interesting to those that care for the things that he describes, his fancy amuses, or charms or often stimulates our ideas. His short stories are interesting to a student of literature because they did much to give a definite character to a literary form which has since become of great importance. His novels are exquisite specimens of what he himself called the romance, in which the figures and scenes are laid in a world a little more poetic than that which makes up our daily surrounding. But Hawthorne's really great power lay in his ability to depict life so that we are made keenly aware of the dominating influence of moral motive and moral law

Hawthorne's Tale-Writing

A Reviewby Edgar Allan Poe

In the preface to my sketches of New York Literati, while speaking of the broad distinction between the seeming public and real private opinion respecting our authors, I thus alluded to Nathaniel Hawthorne:--

"For example, Mr. Hawthorne, the author of 'Twice-Told Tales,' is scarcely recognized by the press or by the public, and when noticed at all, is noticed merely to be damned by faint praise. Now, my own opinion of him is, that although his walk is limited and he is fairly to be charged with mannerism, treating all subjects in a similar tone of dreamy innuendo, yet in this walk he evinces extraordinary genius, having no rival either in America or elsewhere; and this opinion I have never heard gainsaid by any one literary person in the country. That this opinion, however, is a spoken and not a written one, is referable to the facts, first, that Mr. Hawthorne is a poor man, and, secondly, that he is not an ubiquitous quack."

The reputation of the author of "Twice-Told Tales" has been confined, indeed, until very lately, to literary society; and I have not been wrong, perhaps, in citing him as the example, par excellence, in this country, of the privately-admired and publicly-unappreciated man of genius. Within the last year or two, it is true, an occasional critic has been urged, by honest indignation, into very warm approval. Mr. Webber, for instance, (than whom no one has a keener relish for that kind of writing which Mr. Hawthorne has best illustrated,) gave us, in a late number of "The American Review," a cordial and certainly a full tribute to his talents; and since the issue of the "Mosses from an Old Manse," criticisms of similar tone have been by no means infrequent in our more authoritative journals. I can call to mind few reviews of Hawthorne published before the "Mosses." One I remember in "Arcturus" (edited by Matthews and Duyckinck) for May, 1841; another in the "American Monthly" (edited by Hoffman and Herbert) for March, 1838; a third in the ninety-sixth number of the "North American Review." These criticisms, however, seemed to have little effect on the popular taste--at least, if we are to form any idea of the popular taste by reference to its expression in the newspapers, or by the sale of the author's book. It was never the fashion (until lately) to speak of him in any summary of our best authors. The daily critics would say, on such occasions, "Is there not Irving and Cooper, and Bryant and Paulding, and—Smith?" or, "Have we not Halleck and Dana, and Longfellow and—Thompson?" or, "Can we not point triumphantly to our own Sprague, Willis, Channing, Bancroft, Prescott and—Jenkins?" but these unanswerable queries were never wound up by the name of Hawthorne.

Beyond doubt, this inappreciation of him on the part of the public arose chiefly from the two causes to which I have referred--from the facts that he is neither a man of wealth nor a quack,--but these are insufficient to account for the whole effect. No small portion of it is attributable to the very marked idiosyncrasy of Mr. Hawthorne himself. In one sense, and in great measure, to be peculiar is to be original, and than the true originality there is no higher literary virtue. This true or commendable originality, however, implies not the uniform, but the continuous peculiarity--a peculiarity springing from ever-active vigor of fancy--better still if from ever-present force of imagination, giving its own hue, its own character to everything it touches, and, especially self impelled to touch everything.

It is often said, inconsiderately, that very original writers always fail in popularity--that such and such persons are too original to be comprehended by the mass. "Too peculiar," should be the phrase, "too idiosyncratic." It is, in fact, the excitable, undisciplined and child-like popular mind which most keenly feels the original. The criticism of the conservatives, of the hackneys, of the cultivated old clergymen of the "North American Review," is precisely the criticism which condemns and alone condemns it. "It becometh not a divine," saith Lord Coke, "to be of a fiery and salamandrine spirit." Their conscience allowing them to move nothing themselves, these dignitaries have a holy horror of being moved. "Give us quietude," they say. Opening their mouths with proper caution, they sigh forth the word "Repose." And this is, indeed, the one thing they should be permitted to enjoy, if only upon the Christian principle of give and take.

The fact is, that if Mr. Hawthorne were really original, he could not fail of making himself felt by the public. But the fact is, he is not original in any sense. Those who speak of him as original, mean nothing more than that he differs in his manner or tone, and in his choice of subjects, from any author of their acquaintance--their acquaintance not extending to the German Tieck, whose manner, in some of his works, is absolutely identical with that habitual to Hawthorne. But it is clear that the element of the literary originality is novelty. The element of its appreciation by the reader is the reader's sense of the new. Whatever gives him a new and insomuch a pleasurable emotion, he considers original, and whoever frequently gives him such emotion, he considers an original writer. In a word, it is by the sum total of these emotions that he decides upon the writer's claim to originality. I may observe here, however, that there is clearly a point at which even novelty itself would cease to produce the Iegitimate originality, if we judge this originality, as we should, by the effect designed: this point is that at which novelty becomes nothing novel; and here the artist, to preserve his originality, will subside into the common-place. No one, I think, has noticed that, merely through inattention to this matter, Moore has comparatively failed in his "Lalla Rookh." Few readers, and indeed few critics, have commended this poem for originality--and, in fact, the effect, originality, is not produced by it--yet no work of equal size so abounds in the happiest originalities, individually considered. They are so excessive as, in the end, to deaden in the reader all capacity for their appreciation.

These points properly understood, it will be seen that the critic (unacquainted with Tieck) who reads a single tale or essay by Hawthorne, may be justified in thinking him original; but the tone, or manner, or choice of subject, which induces in this critic the sense of the new, will--if not in a second tale, at least in a third and all subsequent ones--not only fail of inducing it, but bring about an exactly antagonistic impression. In concluding a volume and more especially in concluding all the volumes of the author, the critic will abandon his first design of calling him "original," and content himself with styling him "peculiar."

With the vague opinion that to be original is to be unpopular, I could, indeed, agree, were I to adopt an understanding of originality which, to my surprise, I have known adopted by many who have a right to be called critical. They have limited, in a love for mere words, the literary to the metaphysical originality. They regard as original in Ietters, only such combinations of thought, of incident, and so forth, as are, in fact, absolutely novel. It is clear, however, not only that it is the novelty of effect alone which is worth consideration, but that this effect is best wrought, for the end of all fictitious composition, pleasure, by shunning rather than by seeking the absolute novelty of combination. Originality, thus understood, tasks and startles the intellect, and so brings into undue action the faculties to which, in the lighter literature, we least appeal. And thus understood, it cannot fail to prove unpopular with the masses, who, seeking in this literature amusement, are positively offended by instruction. But the true originality--true in respect of its purpose--is that which, in bringing out the half-formed, the reluctant, or the unexpressed fancies of mankind, or in exciting the more delicate pulses of the heart's passion, or in giving birth to some universal sentiment or instinct in embryo, thus combines with the pleasurable effect of apparent novelty, a real egotistic delight. The reader, in the case first supposed, (that of the absolute novelty,) is excited, but embarrassed, disturbed, in some degree even pained at his own want of perception, at his own folly in not having himself hit upon the idea. In the second case, his pleasure is doubled. He is filled with an intrinsic and extrinsic delight. He feels and intensely enjoys the seeming novelty of the thought, enjoys it as really novel, as absolutely original with the writer--and himself. They two he fancies, have, alone of all men, thought thus. They two have, together, created this thing. Henceforward there is a bond of sympathy between them, a sympathy which irradiates every subsequent page of the book.

There is a species of writing which, with some difficulty, may be admitted as a lower degree of what I have called the true original. In its perusal, we say to ourselves, not "how original this is!" nor "here is an idea which I and the author have alone entertained," but "here is a charmingly obvious fancy," or sometimes even, "here is a thought which I am not sure has ever occurred to myself, but which, of course, has occurred to all the rest of the world." This kind of composition (which still appertains to a high order) is usually designated as "the natural." It has little external resemblance, but strong internal affinity to the true original, if, indeed, as I have suggested, it is not of this latter an inferior degree. It is best exemplified, among English writers, in Addison, Irving and Hawthorne. The "ease" which is so often spoken of as its distinguishing feature, it has been the fashion to regard as ease in appearance alone, as a point of really difficult attainment. This idea, however, must be received with some reservation. The natural style is difficult only to those who should never intermeddle with it--to the unnatural. It is but the result of writing with the understanding, or with the instinct, that the tone, in composition, should be that which, at any given point or upon any given topic, would be the tone of the great mass of humanity. The author who, after the manner of the North Americans, is merely at all times quiet, is, of course, upon most occasions, merely silly or stupid, and has no more right to be thought "easy" or "natural" than has a cockney exquisite or the sleeping beauty in the wax-works.

The "peculiarity" or sameness, or monotone of Hawthorne, would, in its mere character of "peculiarity," and without reference to what is the peculiarity, suffice to deprive him of all chance of popular appreciation. But at his failure to be appreciated, we can, of course, no longer wonder, when we find him monotonous at decidedly the worst of all possible points--at that point which, having the least concern with Nature, is the farthest removed from the popular intellect, from the popular sentiment and from the popular taste. I allude to the strain of allegory which completely overwhelms the greater number of his subjects, and which in some measure interferes with the direct conduct of absolutely all.

In defence of allegory, (however, or for whatever object, employed,) there is scarcely one respectable word to be said. Its best appeals are made to the fancy—-that is to say, to our sense of adaptation, not of matters proper, but of matters improper for the purpose, of the real with the unreal, having never more of intelligible connection than has something with nothing, never half so much of effective affinity as has the substance for the shadow. The deepest emotion aroused within us by the happiest allegory, as allegory, is a very, very imperfectly satisfied sense of the writer's ingenuity in overcoming a difficulty we should have preferred his not having attempted to overcome. The fallacy of the idea that allegory, in any of its moods, can be made to enforce a truth--that metaphor, for example, may illustrate as well as embellish an argument--could be promptly demonstrated: the converse of the supposed fact might be shown, indeed, with very little trouble--but these are topics foreign to my present purpose. One thing is clear, that if allegory ever establishes a fact, it is by dint of overturning a fiction. Where the suggested meaning runs through the obvious one in a very profound under-current, so as never to interfere with the upper one without our own volition, so as never to show itself unless called to the surface, there only, for the proper uses of fictitious narrative, is it available at all. Under the best circumstances, it must always interfere with that unity of effect which, to the artist, is worth all the allegory in the world. Its vital injury, however, it rendered to the most vitally important point in fiction--that of earnestness or verisimilitude. That "The Pilgrim's Progress" is a ludicrously over-rated book, owing its seeming popularity to one or two of those accidents in critical literature which by the critical are sufficiently well understood, is a matter upon which no two thinking people disagree; but the pleasure derivable from it, in any sense, will be found in the direct ratio of the reader's capacity to smother its true purpose, in the direct ratio of his ability to keep the allegory out of sight, or of his inability to comprehend it. Of allegory properly handled, judiciously subdued, seen only as a shadow or by suggestive glimpses, and making its nearest approach to truth in a not obtrusive and therefore not unpleasant appositeness, the "Undine" of De La Motte Fouqué is the best, and undoubtedly a very remarkable specimen.

The obvious causes, however, which have prevented Mr. Hawthorne's popularity, do not suffice to condemn him in the eyes of the few who belong properly to books, and to whom books, perhaps, do not quite so properly belong. These few estimate an author, not as do the public, altogether by what he does, but in great measure--indeed, even in the greatest measure--by what he evinces a capability of doing. In this view, Hawthorne stands among literary people in America in much the same light as Coleridge in England. The few, also, through a certain warping of the taste, which long pondering upon books as books never fails to induce, are not in condition to view the errors of a scholar as errors altogether. At any time these gentlemen are prone to think the public not right rather than an educated author wrong. But the simple truth is, that the writer who aims at impressing the people, is always wrong when he fails in forcing that people to receive the impression. How far Mr. Hawthorne has addressed the people at all, is, of course, not a question for me to decide. His books afford strong internal evidence of having been written to himself and his particular friends alone.

There has long existed in literature a fatal and unfounded prejudice, which it will be the office of this age to overthrow--the idea that the mere bulk of a work must enter largely into our estimate of its merit. I do not suppose even the weakest of the Quarterly reviewers weak enough to maintain that in a book's size or mass, abstractly considered, there is anything which especially calls for our admiration. A mountain, simply through the sensation of physical magnitude which it conveys, does, indeed, affect us with a sense of the sublime, but we cannot admit any such influence in the contemplation even of "The Columbiad." The Quarterlies themselves will not admit it. And yet, what else are we to understand by their continual prating about "sustained effort?" Granted that this sustained effort has accomplished an epic--let us then admire the effort, (if this be a thing admirable,) but certainly not the epic on the effort's account. Common sense, in the time to come, may possibly insist upon measuring a work of art rather by the object it fulfils, by the impression it makes, than by the time it took to fulfil the object, or by the extent of "sustained effort" which became necessary to produce the impression. The fact is, that perseverance is one thing and genius quite another; nor can all the transcendentalists in Heathendom confound them.

Full of its bulky ideas, the last number of the "North American Review," in what it imagines a criticism on Simms, "honestly avows that it has little opinion of the mere tale;" and the honesty of the avowal is in no slight degree guarantied by the fact that this Review has never yet been known to put forth an opinion which was not a very little one indeed.

The tale proper affords the fairest field which can be afforded by the wide domains of mere prose, for the exercise of the highest genius. Were I bidden to say how this genius could be most advantageously employed for the best display of its powers, I should answer, without hesitation, "in the composition of a rhymed poem not to exceed in length what might be perused in an hour." Within this limit alone can the noblest order of poetry exist. I have discussed this topic elsewhere, and need here repeat only that the phrase "a long poem" embodies a paradox. A poem must intensely excite. Excitement is its province, its essentiality. Its value is in the ratio of its (elevating) excitement. But all excitement is, from a psychal necessity, transient. It cannot be sustained through a poem of great length. In the course of an hour's reading, at most, it flags, fails; and then the poem is, in effect, no longer such. Men admire, but are wearied with the "Paradise Lost;" for platitude follows platitude, inevitably, at regular interspaces, (the depressions between the waves of excitement,) until the poem, (which, properly considered, is but a succession of brief poems,) having been brought to an end, we discover that the sums of our pleasure and of displeasure have been very nearly equal. The absolute, ultimate or aggregate effect of any epic under the sun is, for these reasons, a nullity. "The Iliad," in its form of epic, has but an imaginary existence; granting it real, however, I can only say of it that it is based on a primitive sense of Art. Of the modern epic nothing can be so well said as that it is a blindfold imitation of a "come-by-chance." By and by these propositions will be understood as self-evident, and in the meantime will not be essentially damaged as truths by being generally condemned as falsities.

A poem too brief, on the other hand, may produce a sharp or vivid, but never a profound or enduring impression. Without a certain continuity, without a certain duration or repetition of the cause, the soul is seldom moved to the effect. There must be the dropping of the water on the rock. There must be the pressing steadily down of the stamp upon the wax. De Béranger has wrought brilliant things, pungent and spirit-stirring, but most of them are too immassive to have momentum, and, as so many feathers of fancy, have been blown aloft only to be whistled down the wind. Brevity, indeed, may degenerate into epigrammatism, but this danger does not prevent extreme length from being the one unpardonable sin.

Were I called upon, however, to designate that class of composition which, next to such a poem as I have suggested, should best fulfil the demands and serve the purposes of ambitious genius, should offer it the most advantageous field of exertion, and afford it the fairest opportunity of display, I should speak at once of the brief prose tale. History, philosophy, and other matters of that kind, we leave out of the question, of course. Of course, I say, and in spite of the gray-beards. These graver topics, to end of time, will be best illustrated by what a discriminating world, turning up its nose at the drab pamphlets, has agreed to understand as talent. The ordinary novel is objectionable, from its length, for reasons analogous to those which render length objectionable in the poem. As the novel cannot be read at one sitting, it cannot avail itself of the immense benefit of totality. Worldly interests, intervening during the pauses of perusal, modify, counteract and annul the impressions intended. But simple cessation in reading would, of itself, be sufficient to destroy the true unity. In the brief tale, however, the author is enabled to carry out his full design without interruption. During the hour of perusal, the soul of the reader is at the writer's control.

A skillful artist has constructed a tale. He has not fashioned his thoughts to accommodate his incidents, but having deliberately conceived a certain single effect to be wrought, he then invents such incidents, he then combines such events, and discusses them in such tone as may best serve him in establishing this preconceived effect. If his very first sentence tend not to the outbringing of this effect, then in his very first step has he committed a blunder. In the whole composition there should be no word written of which the tendency, direct or indirect, is not to the one pre-established design. And by such means, with such care and skill, a picture is at length painted which leaves in the mind of him who contemplates it with a kindred art, a sense of the fullest satisfaction. The idea of the tale, its thesis, has been presented unblemished, because undisturbed--an end absolutely demanded, yet, in the novel, altogether unattainable.

Of skillfully-constructed tales--I speak now without reference to other points, some of them more important than construction--there are very few American specimens. I am acquainted with no better one, upon the whole, than the "Murder Will Out" of Mr. Simms, and this has some glaring defects. The "Tales of a Traveler," by Irving, are graceful and impressive narratives--"The Young Italian" is especially good--but there is not one of the series which can be commended as a whole. In many of them the interest is subdivided and frittered away, and their conclusions are insuffciently climacic. In the higher requisites of composition, John Neal's magazine stories excel--I mean in vigor of thought, picturesque combination of incident, and so forth--but they ramble too much, and invariably break down just before coming to an end, as if the writer had received a sudden and irresistible summons to dinner, and thought it incumbent upon him to make a finish of his story before going. One of the happiest and best-sustained tales I have seen, is "Jack Long; or, The Shot in the Eye," by Charles W. Webber, the assistant editor of Mr. Colton's "American Review." But in general skill of construction, the tales of Willis, I think, surpass those of any American writer--with the exception of Mr. Hawthorne.

I must defer to the better opportunity of a volume now in hand, a full discussion of his individual pieces, and hasten to conclude this paper with a summary of his merits and demerits.

He is peculiar and not original--unless in those detailed fancies and detached thoughts which his want of general originality will deprive of the appreciation due to them, in preventing them forever reaching the public eye. He is infinitely too fond of allegory, and can never hope for popularity so long as he persists in it. This he will not do, for allegory is at war with the whole tone of his nature, which disports itself never so well as when escaping from the mysticism of his Goodman Browns and White Old Maids into the hearty, genial , but still Indian-summer sunshine of his Wakefields and Little Annie's Rambles. Indeed, his spirit of "metaphor run-mad" is clearly imbibed from the phalanx and phalanstery atmosphere in which he has been so long struggling for breath. He has not half the material for the exclusiveness of authorship that he possesses for his universality. He has the purest style, the finest taste, the most available scholarship, the most delicate humor, the most touching pathos, the most radiant imagination, the most consummate ingenuity; and with these varied good qualities he has done well as a mystic. But is there any one of these qualities which should prevent his doing doubly as well in a career of honest, upright, sensible, prehensible, and comprehensible things? Let him mend his pen, get a bottle of visible ink, come out from the Old Manse, cut Mr. Alcott, hang (if possible) the editor of "The Dial," and throw out of the window to the pigs all his odd numbers of "The North American Review."

The Old Manse

THE AUTHOR MAKES THE READER ACQUAINTED WITH HIS ABODE

BETWEEN two tall gate-posts of rough-hewn stone, (the gate itself having fallen from its hinges, at some unknown epoch,) we beheld the gray front of the old parsonage, terminating the vista of an avenue of black-ash trees. It was now a twelvemonth since the funeral procession of the venerable clergyman, its last inhabitant, had turned from that gate-way towards the village burying-ground. The wheel-track, leading to the door, as well as the whole breadth of the avenue, was almost overgrown with grass, affording dainty mouthfuls to two or three vagrant cows, and an old white horse, who had his own living to pick up along the roadside. The glimmering shadows, that lay half-asleep between the door of the house and the public highway, were a kind of spiritual medium, seen through which, the edifice had not quite the aspect of belonging to the material world. Certainly it had little in common with those ordinary abodes, which stand so imminent upon the road that every passer-by can thrust his head, as it were, into the domestic circle. From these quiet windows, the figures of passing travellers looked too remote and dim to disturb the sense of privacy. In its near retirement, and accessible seclusion, it was the very spot for the residence of a clergyman; a man not estranged from human life, yet enveloped, in the midst of it, with a veil woven of intermingled gloom and brightness. It was worthy to have been one of the time-honored parsonages of England, in which, through many generations, a succession of holy occupants pass from youth to age, and bequeath each an inheritance of sanctity to pervade the house and hover over it, as with an atmosphere.

Nor, in truth, had the Old Manse ever been prophaned by a lay occupant, until that memorable summer-afternoon when I entered it as my home. A priest had built it; a priest had succeeded to it; other priestly men, from time to time, had dwelt in it; and children, born in its chambers, had grown up to assume the priestly character. It was awful to reflect how many sermons must have been written there. The latest inhabitant alone--he, by whose translation to Paradise the dwelling was left vacant--had penned nearly three thousand discourses, besides the better, if not the greater number, that gushed living from his lips. How often, no doubt, had he paced to-and-fro along the avenue, attuning his meditations, to the sighs and gentle murmurs, and deep and solemn peals of the wind, among the lofty tops of the trees! In that variety of natural utterances, he could find something accordant with every passage of his sermon, were it of tenderness or reverential fear. The boughs over my head seemed shadowy with solemn thoughts, as well as with rustling leaves. I took shame to myself for having been so long a writer of idle stories, and ventured to hope that wisdom would descend upon me with the falling leaves of the avenue; and that I should light upon an intellectual treasure in the Old Manse, well worth those hoards of long-hidden gold, which people seek for in moss-grown houses. Profound treatises of morality;--a layman's unprofessional, and therefore unprejudiced views of religion;--histories, (such as Bancroft might have written, had he taken up his abode here, as he once purposed,) bright with picture, gleaming over a depth of philosophic thought;--these were the works that might fitly have flowed from such a retirement. In the humblest event, I resolved at least to achieve a novel, that should evolve some deep lesson, and should possess physical substance enough to stand alone.

In furtherance of my design, and as if to leave me no pretext for not fulfilling it, there was, in the rear of the house, the most delightful little nook of a study that ever afforded its snug seclusion to a scholar. It was here that Emerson wrote 'Nature'; for he was then an inhabitant of the Manse, and used to watch the Assyrian dawn and the Paphian sunset and moonrise, from the summit of our eastern hill. When I first saw the room, its walls were blackened with the smoke of unnumbered years, and made still blacker by the grim prints of Puritan ministers that hung around. These worthies looked strangely like bad angels, or, at least, like men who had wrestled so continually and so sternly with the devil, that somewhat of his sooty fierceness had been imparted to their own visages. They had all vanished now. A cheerful coat of paint, and golden-tinted paper-hangings, lighted up the small apartment; while the shadow of a willow-tree, that swept against the overhanging eaves, attempered the cheery western sunshine. In place of the grim prints, there was the sweet and lovely head of one of Raphael's Madonnas, and two pleasant little pictures of the Lake of Como. The only other decorations were a purple vase of flowers, always fresh, and a bronze one containing graceful ferns. My books (few, and by no means choice; for they were chiefly such waifs as chance had thrown in my way) stood in order about the room, seldom to be disturbed.

The study had three windows, set with little, old-fashioned panes of glass, each with a crack across it. The two on the western side looked, or rather peeped, between the willow-branches, down into the orchard, with glimpses of the river through the trees. The third, facing northward, commanded a broader view of the river, at a spot where its hitherto obscure waters gleam forth into the light of history. It was at this window that the clergyman, who then dwelt in the Manse, stood watching the outbreak of a long and deadly struggle between two nations; he saw the irregular array of his parishioners on the farther side of the river, and the glittering line of the British, on the hither bank. He awaited, in an agony of suspense, the rattle of the musketry. It came--and there needed but a gentle wind to sweep the battle-smoke around this quiet house.

Perhaps the reader--whom I cannot help considering as my guest in the Old Manse, and entitled to all courtesy in the way of sight-showing--perhaps he will choose to take a nearer view of the memorable spot. We stand now on the river's brink. It may well be called the Concord--the river of peace and quietness--for it is certainly the most unexcitable and sluggish stream that ever loitered, imperceptibly, towards its eternity, the sea. Positively, I had lived three weeks beside it, before it grew quite clear to my perception which way the current flowed. It never has a vivacious aspect, except when a north-western breeze is vexing its surface, on a sunshiny day. From the incurable indolence of its nature, the stream is happily incapable of becoming the slave of human ingenuity, as is the fate of so many a wild, free mountain torrent. While all things else are compelled to subserve some useful purpose, it idles its sluggish life away, in lazy liberty, without turning a solitary spindle, or affording even water-power enough to grind the corn that grows upon its banks. The torpor of its movement allows it nowhere a bright pebbly shore, nor so much as a narrow strip of glistening sand, in any part of its course. It slumbers between broad prairies, kissing the long meadow-grass, and bathes the overhanging boughs of elder-bushes and willows, or the roots of elms and ash-trees, and clumps of maples. Flags and rushes grow along its plashy shore; the yellow water-lily spreads its broad, flat leaves on the margin; and the fragrant white pond-lily abounds, generally selecting a position just so far from the river's brink, that it cannot be grasped, save at the hazard of plunging in.

Itis a marvel whence this perfect flower derives its loveliness and perfume, springing, as it does, from the black mud over which the river sleeps, and where lurk the slimy eel, and speckled frog, and the mud turtle, whom continual washing cannot cleanse. It is the very same black mud out of which the yellow lily sucks its obscene life and noisome odor. Thus we see, too, in the world, that some persons assimilate only what is ugly and evil from the same moral circumstances which supply good and beautiful results--the fragrance of celestial flowers--to the daily life of others.

Thereader must not, from any testimony of mine, contract a dislike towards our slumberous stream. In the light of a calm and golden sunset, it becomes lovely beyond expression; the more lovely for the quietude that so well accords with the hour, when even the wind, after blustering all day long, usually hushes itself to rest. Each tree and rock, and every blade of grass, is distinctly imaged, and, however unsightly in reality, assumes ideal beauty in the reflection. The minutest things of earth, and the broad aspect of the firmament, are pictured equally without effort, and with the same felicity of success. All the sky glows downward at our feet; the rich clouds float through the unruffled bosom of the stream, like heavenly thoughts through a peaceful heart. We will not, then, malign our river as gross and impure, while it can glorify itself with so adequate a picture of the heaven that broods above it; or, if we remember its tawny hue and the muddiness of its bed, let it be a symbol that the earthliest human soul has an infinite spiritual capacity, and may contain the better world within its depths. But, indeed, the same lesson might be drawn out of any mud-puddle in the streets of a city--and, being taught us everywhere, it must be true.

Come;we have pursued a somewhat devious track, in our walk to the battle-ground. Here we are, at the point where the river was crossed by the old bridge, the possession of which was the immediate object of the contest. On the hither side, grow two or three elms, throwing a wide circumference of shade, but which must have been planted at some period within the threescore years and ten, that have passed since the battle-day. On the farther shore, overhung by a clump of elder-bushes, we discern the stone abutment of the bridge. Looking down into the river, I once discovered some heavy fragments of the timbers, all green with half-a-century's growth of water-moss; for, during that length of time, the tramp of horses and human footsteps have ceased, along this ancient highway. The stream has here about the breadth of twenty strokes of a swimmer's arm; a space not too wide, when the bullets were whistling across. Old people, who dwell hereabouts, will point out the very spots, on the western bank, where our countrymen fell down and died; and, on this side of the river, an obelisk of granite has grown up from the soil that was fertilized with British blood. The monument, not more than twenty feet in height, is such as it befitted the inhabitants of a village to erect, in illustration of a matter of local interest, rather than what was suitable to commemorate an epoch of national history. Still, by the fathers of the village this famous deed was done; and their descendants might rightfully claim the privilege of building a memorial.

Ahumbler token of the fight, yet a more interesting one than the granite obelisk, may be seen close under the stonewall, which separates the battle-ground from the precincts of the parsonage. It is the grave--marked by a small, moss-grown fragment of stone at the head, and another at the foot--the grave of two British soldiers, who were slain in the skirmish, and have ever since slept peacefully where Zechariah Brown and Thomas Davis buried them. Soon was their warfare ended;--a weary night-march from Boston--a rattling volley of musketry across the river;--and then these many years of rest! In the long procession of slain invaders, who passed into eternity from the battle-fields of the Revolution, these two nameless soldiers led the way.

Lowell,the poet, as we were once standing over this grave, told me a tradition in reference to one of the inhabitants below. The story has something deeply impressive, though its circumstances cannot altogether be reconciled with probability. A youth, in the service of the clergyman, happened to be chopping wood, that April morning, at the back door of the Manse; and when the noise of battle rang from side to side of the bridge, he hastened across the intervening field, to see what might be going forward. It is rather strange, by the way, that this lad should have been so diligently at work, when the whole population of town and county were startled out of their customary business, by the advance of the British troops. Be that as it might, the tradition says that the lad now left his task, and hurried to the battle-field, with the axe still in his hand. The British had by this time retreated--the Americans were in pursuit--and the late scene of strife was thus deserted by both parties. Two soldiers lay on the ground; one was a corpse; but, as the young New-Englander drew nigh, the other Briton raised himself painfully upon his hands and knees, and gave a ghastly stare into his face. The boy--it must have been a nervous impulse, without purpose, without thought, and betokening a sensitive and impressible nature, rather than a hardened one--the boy uplifted his axe, and dealt the wounded soldier a fierce and fatal blow upon the head.

Icould wish that the grave might be opened; for I would fain know whether either of the skeleton soldiers have the mark of an axe in his skull. The story comes home to me like truth. Oftentimes, as an intellectual and moral exercise, I have sought to follow that poor youth through his subsequent career, and observe how his soul was tortured by the blood-stain, contracted, as it had been, before the long custom of war had robbed human life of its sanctity, and while it still seemed murderous to slay a brother man. This one circumstance has borne more fruit for me, than all that history tells us of the fight.

Manystrangers come, in the summer-time, to view the battle-ground. For my own part, I have never found my imagination much excited by this, or any other scene of historic celebrity; nor would the placid margin of the river have lost any of its charm for me, had men never fought and died there. There is a wilder interest in the tract of land--perhaps a hundred yards in breadth--which extends between the battle-field and the northern face of our Old Manse, with its contiguous avenue and orchard. Here, in some unknown age, before the white man came, stood an Indian village, convenient to the river, whence its inhabitants must have drawn so large a part of their subsistence. The site is identified by the spear and arrow-heads, the chisels, and other implements of war, labor, and the chase, which the plough turns up from the soil. You see a splinter of stone, half hidden beneath a sod; it looks like nothing worthy of note; but, if you have faith enough to pick it up--behold a relic! Thoreau, who has a strange faculty of finding what the Indians have left behind them, first set me on the search; and I afterwards enriched myself with some very perfect specimens, so rudely wrought that it seemed almost as if chance had fashioned them. Their great charm consists in this rudeness, and in the individuality of each article, so different from the productions of civilized machinery, which shapes everything on one pattern. There is an exquisite delight, too, in picking up, for one's self, an arrow-head that was dropt centuries ago, and has never been handled since, and which we thus receive directly from the hand of the red hunter, who purposed to shoot it at his game, or at an enemy. Such an incident builds up again the Indian village, amid its encircling forest, and recalls to life the painted chiefs and warriors, the squaws at their household toil, and the children sporting among the wigwams; while the little wind-rocked papoose swings from the branch of a tree. It can hardly be told whether it is a joy or a pain, after such a momentary vision, to gaze around in the broad daylight of reality, and see stone-fences, white houses, potatoe-fields, and men doggedly hoeing, in their shirt-sleeves and homespun pantaloons. But this is nonsense. The Old Manse is better than a thousand wigwams.

The