Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Librorium Editions

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

This is a most amusing little story of what we may call the genteel farce kind. Mrs. Pendleton, who has been a pronounced flirt in her married life, becomes a widow at twenty-four, and receives simultaneous offers of marriage from four admirers. It must, she thinks, be a practical joke; to avenge the insult she engages herself to the four.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 46

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

LITTLE NOVELS BY

FAVOURITE AUTHORS

Mrs. Pendleton’s

Four-in-hand

Gertrude Atherton

Mrs. Pendleton’s

Four-in-hand

BY

GERTRUDE ATHERTON

AUTHOR OF “THE CONQUEROR,” ETC.

Copyright, 1902,

By MRS. GERTRUDE ATHERTON.

Copyright, 1903,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up, electrotyped, and published June, 1903.

Norwood Press

ILLUSTRATIONS

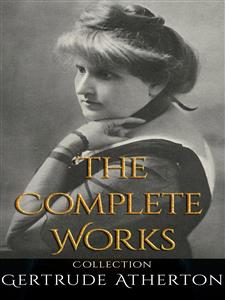

Portrait of Gertrude Atherton

Frontispiece

FACING PAGE

“‘I have been insulted’”

11

“‘Well, why don’t you go?’”

87

MRS. PENDLETON’S

FOUR-IN-HAND

I

essica, her hands clenched and teeth set, stood looking with hard eyes at a small heap of letters lying on the floor. The sun, blazing through the open window, made her blink unconsciously, and the ocean’s deep voice rising to the Newport sands seemed to reiterate:—

“Contempt! Contempt!”

Tall, finely pointed with the indescribable air and style of the New York woman, she did not suggest intimate knowledge of the word the ocean hurled to her. In that moss-green room, with her haughty face and clean skin, her severe faultless gown, she rather suggested the type to whom poets a century hence would indite their sonnets—when she and her kind had been set in the frame of the past. And if her dress was conventional, she had let imagination play with her hair. The clear evasive colour of flame, it was brushed down to her neck, parted, crossed, and brought tightly up each side of her head just behind her ears. Meeting above her bang, the curling ends allowed to fly loose, it vaguely resembled Medusa’s wreath. Her eyes were grey, the colour of mid-ocean, calm, beneath a grey sky. Not twenty-four, she had the repose and “air” of one whose cradle had been rocked by Society’s foot; and although at this moment her pride was in the dust, there was more anger than shame in her face.

The door opened and her hostess entered. As Mrs. Pendleton turned slowly and looked at her, Miss Decker gave a little cry.

“‘I HAVE BEEN INSULTED.’”

“Jessica!” she said, “what is the matter?”

“I have been insulted,” said Mrs. Pendleton, deliberately. She felt a savage pleasure in further humiliating herself.

“Insulted! You!” Miss Decker’s correct voice and calm brown eyes could not have expressed more surprise and horror if a foreign diplomatist had snapped his fingers in the face of the President’s wife. Even her sleek brown hair almost quivered.

“Yes,” Mrs. Pendleton went on in the same measured tones; “four men have told me how much they despise me.” She walked slowly up and down the room. Miss Decker sank upon the divan, incredulity, curiosity, expectation, feminine satisfaction marching across her face in rapid procession.

“I have always maintained that a married woman has a perfect right to flirt,” continued Mrs. Pendleton. “The more if she has married an old man and life is somewhat of a bore. ‘Why do you marry an old man?’ snaps the virtuous world. ‘What a contemptible creature you are to marry for anything but love!’ it cries, as it eats the dust at Mammon’s feet. I married an old man because with the wisdom of twenty, I had made up my mind that I could never love and that position and wealth alone made up the sum of existence. I had more excuse than a girl who has been always poor, for I had never known the arithmetic of money until my father failed, the year before I married. People who have never known wealth do not realise the purely physical suffering of those inured to luxury and suddenly bereft of it: it makes no difference what one’s will or strength of character is. So—I married Mr. Pendleton. So—I amused myself with other men. Mr. Pendleton gave me my head, because I kept clear of scandal: he knew my pride. Now, if I had spent my life demoralising myself and the society that received me, I could not be more bitterly punished. I suppose I deserve it. I suppose that the married flirt is just as poor and paltry and contemptible a creature as the moralist and the minister depict her. We measure morals by results. Therefore I hold to-day that it is the business of a lifetime to throw stones at the married flirt.”

“For Heaven’s sake,” cried Miss Decker, in a tone of exasperation, “stop moralising and tell me what has happened!”

“Do you remember Clarence Trent, Edward Dedham, John Severance, Norton Boswell?”

“Do I? Poor moths!”

“They were apparently devoted to me.”

Dryly: “Apparently.”

“How long is it since Mr. Pendleton’s death?”

“About—he died on the sixteenth—why, yes, it was six months yesterday since he died.”

“Exactly. You see these four notes on the floor? They are four proposals—four proposals”—and she gave a short hard laugh through lips whose red had suddenly faded—“from the four men I have just mentioned.”

Miss Decker gasped. “Four proposals! Then what on earth are you angry about?”

Mrs. Pendleton’s lip curled scornfully. She did not condescend to answer at once. “You are clever enough at times,” she said coldly, after a moment. “It is odd you cannot grasp the very palpable fact that four proposals received on the same day, by the same mail, from four men who are each other’s most intimate friends, can mean but one thing—a practical joke. Oh!” she cried, the jealously mastered passion springing into her voice, “that is what infuriates me—more even than the insult—that they should think me such a fool as to be so easily deceived! O—h—h!”

“If I remember aright,” ventured Miss Decker, feebly, “the intimacy to which you allude was a thing of the past some time before you disappeared from the world. In fact, they were not on speaking terms.”

“Oh, they have made it up long ago! Don’t make any weak explanations, but tell me how to turn the tables on them. I would give my hair and wear a grey wig—my complexion and paint—to get even with them. And I will. But how? How?”

She paced up and down the room with nervous steps, glancing for inspiration from the delicate etchings on the walls to the divan that was like a moss bank, to the carpet that might have been a patch of forest green, and thence to the sparkling ocean. Miss Decker offered no suggestions. She had perfect faith in the genius of her friend.