Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

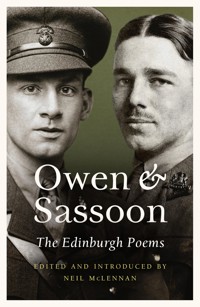

Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, both suffering from shell shock, were sent to convalesce at Craiglockhart hospital in Edinburgh in 1917. Owen, who referred to himself as the 'poet's poet' was unpublished at the time. It was the influence and encouragement of Sassoon during this period that shaped Owen's work. Sassoon was also instrumental in publishing Owen's work posthumously after the war. Here for the first time, collected in a single volume are the poems, written in Edinburgh, of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon. These Edinburgh poems highlight the significance of the time these poets spent together in and around the city.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 78

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published in Great Britain in 2022 by Polygon,an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh EH9 1QS

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © The Estate of Wilfred Owen

Copyright © The Estate of Siegfried Sassoon

Introduction © Neil McLennan

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 978 1 84697 620 9

EBOOK ISBN 978 1 78885 555 6

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Typeset in Verdigris mvb by The Foundry, EdinburghPrinted and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

In Memoriam

Catherine Walker MBE, David Eastwood and Professor Douglas Weir. Three great mentors sadly passed before this book was published.

For Poppyscotland, Royal British Legion Scotland and Forces Children Scotland (formerly Royal Caledonian Education Trust) who, for over a century, have cared for those who have served and serve. After reading this collection I ask you to make a donation to each worthy charity.

Lest We Forget

CONTENTS

Introduction

PART ITHE WILFRED OWEN COLLECTION

Ballad of Lady Yolande [Fragment]

The Fates

The Wrestlers [Fragment]

Sweet is your antique body, not yet young

Song of Songs

Lines to a Beauty seen in Limehouse [Fragment]

Happiness

Has your soul sipped

The Dead-Beat

Fragment from The Hydra No. 10, which may have formed part of ‘The Dead-Beat’

My shy hand

I know the music [Fragment]

Anthem for Doomed Youth

Six O’clock in Princes Street

The Sentry

Inspection

The Next War

Dulce et Decorum Est

Disabled

Winter Song

The Promisers

The Ballad of Many Thorns

Fragment from Albertine Marie Dauthieu’s autograph book

From My Diary, July 1914

Soldier’s Dream

Greater Love

Insensibility

Apologia pro Poemate Meo

The Swift

With an Identity Disc

Music

The city lights along the waterside

Autumnal

Perversity

The Peril of Love

The Poet in Pain

The End

Schoolmistress

Mental Cases

The Chances

S.I.W.

Who is the god of Canongate?

PART IITHE SIEGFRIED SASSOON COLLECTION

Dreamers

Editorial Impressions

Wirers

Does it matter?

How to Die

The Fathers

Sick Leave

Attack

Fight to a Finish

Survivors

The Investiture

Thrushes

Glory of Women

Their Frailty

Break of Day

Prelude: The Troops

Counter-Attack

Twelve Months After

Banishment

Autumn

Acknowledgements

Index of titles

INTRODUCTION

Combatants and observers recording their thoughts and feelings in verse was not unique to the First World War. It will, however, always be distinguished by its poets. Poems written during this period continue to be read, taught and celebrated. Fascination with the war poets, and in particular Wilfred Owen, has grown over time, especially during the 1960s after the publication of Cecil Day Lewis’s The Collected Poems of Wilfred Owen. This edition was particularly resonant with the anti-war sentiment of the Vietnam War era. Since then, Owen and Siegfried Sassoon have become synonymous with remembrance each November. Despite the Treaty of Versailles being signed over a century ago, interest in the poets of the time continues.

Historians continue to use poetry from the war to help gain insight into the experiences of soldiers and civilians. Most people will have studied the war poets in their schooldays – the words of Owen and of Sassoon are popular and used in many classrooms. However, perhaps few will be aware that Owen and Sassoon’s most powerful poems were written while in Edinburgh, Scotland’s capital.

Even though they were together in the city for such a brief time, their story has been told through popular fictionalised accounts: Pat Barker’s 1991 novel, and subsequent film, Regeneration, Stephen MacDonald’s 1983 play Not About Heroes and most recently Terence Davies’ Benediction. These dramatisations give us an insight into the men’s time spent at Craiglockhart War Hospital but they don’t explore the effect they had on each other’s work. This is the first collection to focus on the poems Owen and Sassoon wrote while in Edinburgh. They met there in the middle of August 1917 and would go on to write some of the most important poems of the war. This book pays close attention to how they influenced each other, but it also looks at other factors that played a part in their poetic development.

* * *

Wilfred Owen was injured twice on the Western Front, his second injury in April 1917 affecting him mentally as much as physically. Suffering from what was then called ‘shell shock’ (or ‘neurasthenia’ recorded in the Craiglockhart Hospital Admission and Discharge Registers) he transferred from field dressing stations to field hospitals in France, and then back to the UK for treatment and convalescence. In June 1917 he was sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital, situated near Slateford in Edinburgh. It was opened as a military hospital in 1916, one of a handful of hospitals across the country caring for ‘shell-shocked’ officers.

It was at this hospital that Owen met fellow officer and poet Siegfried Sassoon, a noted and decorated war hero. Sassoon’s reason for being their was perhaps more complex; it was more of a political imprisonment after his criticism of the continuation of the war. His position put him at odds with the military authorities, and a medical referral to Craiglockhart (or ‘Dottyville’ as he nicknamed it) probably enabled him to avoid a court martial and its potential consequences.

On arrival at Craiglockhart, Wilfred Owen was assigned to Dr Arthur John Brock. Brock practiced innovative ‘ergotherapy approaches’ in part inspired by Patrick Geddes. These approaches saw activity and connections with nature take precedent over draconian military-medical ‘cures’ for ‘shell shock’.

Meanwhile, Siegfried Sassoon was assigned to Dr William Halse Rivers Rivers. The pioneering of dream analysis and talking cures that Rivers undertook was akin to modern-day counselling. While Sassoon was perhaps not ‘shell-shocked’ on the surface of it, he certainly had been impacted by the war and indeed his criticism of it. Sassoon and Rivers struck up a strong bond and remained in contact for years to come. Sassoon’s ‘Dreamers’, ‘Counter-Attack’ and most of his other Edinburgh poems are of course about his wartime experience. Dreams played an important part of Sassoon’s doctor’s thinking. Dr Rivers would go on to write Conflict and Dreams (1923).

The methods of Brock and Rivers continued to have an influence on the development of psychiatry in the post-war period, building on a long history of medical innovation in Edinburgh. There is now a Rivers Centre at the Royal Edinburgh Hospital in Morningside. Perhaps one day a Brock Centre may bring together his ergotherapy approaches.

* * *

My interest in war poetry was significantly piqued when I was working at Tynecastle High School in Gorgie. ‘Tynie’, as it is called locally, opened as a technical school in 1912. I took on the post of Head of History at the school in 2007. The school has a fascinating history that I was keen to tap into. I was interested in finding out about famous former pupils students could aspire to. I discovered that Wilfred Owen had taught at the school during his time in Edinburgh. As part of Dr Brock’s ergotherapy programme of cures, some of the recovering ‘shell-shocked’ patients taught classes to the boys at the school as part of their recovery. The headmaster’s logbook noted the arrival of officers to take classes, and Owen’s letters also attest to him teaching at ‘the Big School’ – Tynecastle. Owen taught English Literature whilst the other officers taught map reading, physical exercise, signalling and first aid.

In researching this book, I wanted to find out where Owen was each day, who he was meeting, what he was doing and how that was influencing his writing. I also wanted to find out the effect the city, and its citizens, had on his writing. This included studying Owen’s interactions with Sassoon and how much this impacted on both their creative output. This gives a new perspective to how Edinburgh and the people he met influenced his poetry.

When the two met, it was only Sassoon that was a published poet. However, Owen’s time in Edinburgh saw the publication of his first poems. During his time at Craiglockhart Owen edited six issues of the hospital magazine – The Hydra. The publication had been set up by Dr Brock to engage patients in creative work. Owen not only edited the magazine but also had his first poems published in it. Previously it was thought that Owen had five poems published in his lifetime. However, I have found that in fact he had six. The poems were: (1) ‘Song of Songs’, (The Hydra, 1 September 1917); (2) a fragment of a poem in Owen’s editorial in The Hydra which possibly later made up the poem ‘The Dead-Beat’, this fragment has previously been overlooked in reports of the poet’s published work while he was alive (The Hydra, 1 September 1917); (3) ‘The Next War’, (The Hydra, 29 September 1917); (4) ‘Miners’, (The Nation, 26 January 1918), (5) ‘Futility’, (The Nation, 15 June 1918); (6) ‘Hospital Barge’, (The Nation, 15 June 1918). The Nation, which contained an eclectic range of writing, published both Owen and Sassoon. Its editors were not scared to publish work that criticised the conduct of the war. Overall, Owen’s published material included the small-scale hospital magazine with a very limited circulation, alongside the widely-read national publication.

* * *