16,31 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Fernhurst Books Limited

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

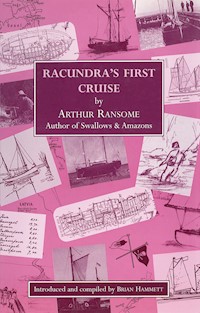

Racundra's First Cruise is Arthur Ransome's account of Racundra's maiden voyage, which took place in August and September 1922. The cruise took him from Riga, in Latvia to Helsingfors (Helsinki) in Finland, via the Moon Sound and Reval (Tallinn) in Estonia and back. His first book on sailing, it was also the first of his titles that achieved such high levels of success. Although reprinted many times in various editions and formats, Fernhurst Books' hardback edition of the title (2003) was the first to use the original text in its entirety - with the original layout, maps and photographs - and also includes an excellent introduction by Brian Hammett containing a treasure trove of previously unpublished writings, essays and photographs. Ransome's first attempts at Baltic sailing, in his two previous boats, Slug and Kittiwake, are also explained in detail using his writings and illustrations. The life of Ransome's beloved Racundra is chronicled to its conclusion and there is an explanation of how he came to write the book. The original illustrations are enhanced by the inclusion of present day photographs of the same locations. Having gone out of print in 2012, this new paperback edition retains all of the original and additional features; bringing back to life Ransome's epic first cruise in his pride and joy, his treasured Racundra.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

.

RACUNDRA’S FIRST CRUISE

Arthur Ransome Societies

The Arthur Ransome Society was founded in 1990 with the aim of promoting interest in Arthur Ransome and his books. For more information on the Society visit their website at www.arthur-ransome.org.uk

In 1997 members of the Society formed The Nancy Blackett Trust with the intention of purchasing and restoring one of Ransome’s own yachts, the Nancy Blackett, and using her to inspire interest in the books and to encourage young people to take up sailing. She now visits many classic boat shows around the country.

To find out more about the trust, or to contribute to the upkeep of the Nancy Blackett please visit their website at www.nancyblackett.org

The Arthur Ransome Trust was formed in 2010, and is dedicated to helping people discover more about Arthur Ransome’s life and writing, primarily through the development of a dedicated Ransome Centre in the southern Lake District. For more information on the Trust please visit their website at www.arthur-ransome-trust.org.uk

RACUNDRA’S FIRST CRUISE

by Arthur Ransome

Introduced and compiled by Brian Hammett

.

This edition first published in 2015 by Fernhurst Books Limited

62 Brandon Parade, Holly Walk, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, CV32 4JE, UK

Tel: +44 (0) 1926 337488 | www.fernhurstbooks.com

Text and pictures © The Arthur Ransome Literary Estate

Introduction © Brian Hammett

First edition published in 1923 by George Allen & Unwin Ltd., London

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a license issued by The Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London, EC1N 8TS, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The Publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

ISBN 978-1-909911-23-9 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-909911-59-8 (eBook)

ISBN 978-1-909911-60-4 (eBook)

Artwork by Creative Byte

Cover design by Simon Balley

RACUNDRA’S FIRST CRUISE

This edition of Racundra’s First Cruise includes the original maps, text and photographs from the 1923 edition. Details of Ransome’s first attempts at Baltic sailing, in his two previous boats Slug and Kittiwake, are included in the introduction.

ARTHUR RANSOME ON THE BUILDING OF RACUNDRA

“I took a deep breath and signed the contract. This was among the few wise things I have done in my life, for, more than anything else, this boat helped me to get back to my proper trade of writing.”

BRIAN HAMMETT

Brian Hammett has compiled this edition of Racundra’s First Cruise. The preface leads us into a treasure trove of unpublished writings, essays and photographs. The life of Ransome’s beloved Racundra is chronicled to its conclusion and there is an explanation of how he came to write the book. The original illustrations are enhanced by the inclusion of present-day photographs of the same locations. Brian Hammett researched the introduction by following Racundra’s route through Latvia and Estonia in his 33 foot gaff cutter AVOLA.

.

CONTENTS

Preface

Page

Introduction

9

Slug

13

Kittiwake

24

Racundra

39

The writing of Racundra’s First Cruise

51

On the Pirate Ship

53

Racundra’s First Cruise

62

Appendix – A Description of Racundra

239

Racundra after Ransome

243

Chronology

251

Bibliography

254

Acknowledgements

256

ARTHUR RANSOME, MASTER AND OWNER.

EVEGENIA SHELEPINA, COOK.

.

Aug 26. 1924

Racundra, River Aa.

A man who owns a little ship Must be forgiven many a slip Committed when on shore. A wife in every foreign port Is unto him accounted naught; And shall a book count more?

A borrowed book that’s not at hand, Being, for safety’s sake, on land Seems but a trivial slip; As for your promised day in Heaven, He’s used to have his weekly seven For Heaven is his ship.

But when at last his sails are furled And he is once more in the world Where little things count much, An aeroplane with swiftest flight Shall bear the book back to delight It’s owner’s greedy clutch.

This poem was written duringRacundra’sthird and last cruise under Ransome’s ownership. Bridget Sanders, W. G. Collingswood’s granddaughter, wrote in autumn 1997: “This poem was sent to Dr. John Rickman at 11 Kent Terrace, Regent’s Park, London NW1, who must have been badgering AR for a book he had lent him. John Rickman was a distinguished psychoanalyst, and pupil of Freud’s.”

.

INTRODUCTION

“I ... took a deep breath and signed the contract. This was among the few wise things I have done in my life, for, more than anything else, this boat helped me to get back to my proper trade of writing.”

Arthur Ransome (1884 – 1967), famous in later life as a children’s author, wrote those words in 1922, having just committed himself to the building of his boatRacundra.The maiden voyage took place from 20th August 1922 until 26th September from Riga, in Latvia, to Helsingfors (Helsinki), in Finland, via the Moon Sound and Reval (Tallinn) in Estonia and back. On completion of the trip he wrote and published his first really successful book,Racundra’s First Cruise.

I am delighted to have the opportunity to introduce a completely new edition of Ransome’s first book on sailing. The original text of the first edition, of which only 1500 copies were printed, has been used in its entirety with the original layout. The original 30 photographs, and four sketch charts, are included together with more unpublished Ransome pictures and recent photographs of many of the places visited during the cruise.

The book has been out of print for many years; the last edition was a paperback published in 1984 by Century Publishers, London, and Hippocrene Books, New York, containing charts but no photographs. The story of how he came to write the book and his sailing activities in the Baltic in the early 1920s makes fascinating reading and tells us a great deal about the man and his approach to sailing and writing.

Ransome went to Russia in 1913 following an unsuccessful first marriage and having successfully defended a court case for libel, by Lord Alfred Douglas, over his bookOscar Wilde, a Critical Study, published in 1912. He had a desire to learn Russian and research and translate Russian fairy tales. His bookOld Peter’s Russian Taleswas published in 1916. He was offered a job as a foreign correspondent and journalist by theDaily Newsand later theManchester Guardian.He reported extensively on Russian matters, the First World War, and the aftermath of the October Revolution. Whilst in Russia he met and fell in love with Evgenia Shelepina, Trotsky’s secretary. They lived together as lovers up until the time that Ivy, his first wife, agreed to a divorce. They married at the British consulate in Reval (Tallinn) on the 24th May 1924.

PETER THE GREAT’S PLAN FOR BALTIC PORT.

Ransome was a prolific writer and had already published 23 books by 1920. The most successful of his books wereBohemia in London,1907,A History of Story Telling, 1909,andOld Peter’s Russian Tales,1916. He had also written two literary critical studies: one on Edgar Alan Poe, 1910, and another on Oscar Wilde, 1912. His life has been extremely well documented in his autobiography, his biography (by Hugh Brogan), and in other books by Christina Hardyment, Roger Wardale, Jeremy Swift and Peter Hunt. A literary society, the Arthur Ransome Society, TARS, is very active and his most famous boatNancy Blackett(aliasGoblin)is run by a charitable trust.

Having had a lifetime interest in Ransome’s work, and having sailed in the Baltic in the year 2000 (where I usedRacundra’s First Cruiseas a pilot book on several occasions), I was interested in discovering more about Ransome’s Baltic sailing and to find out why and how he came to writeRacundra’s First Cruise.I was amazed by the accuracy of his description ofRacundra’ssailing area. The instructions for navigating the coasts of Latvia and Estonia, and in particular the Moon Sound, were as useful and accurate today as they were in the 1920s. The details of port and harbour entry and refuge anchorages also hold good today. Indeed, at one stage in our trip we “happened upon” Baltic Port (now called Paldiski North) whilst running for shelter from a southwesterly gale. We immediately recognised the description of the harbour. Once we had moored up the harbourmaster made us most welcome, told us that we could shelter for as long as we liked, at no charge, and even sent someone to sweep the quay where we had moored. This mirrored the treatment Ransome had experienced 78 years earlier. The harbourmaster and his colleague, the director of Paldiski Port, were very interested in the chapterOld Baltic Port and NewinRacundra’s First Cruiseand, in exchange for a copy, gave us a pamphlet in Russian showing the original plans that Peter the Great had for the area. Ransome mentions on several occasions the uncompleted causeway and the old fort, both of which still exist today.

Ransome’s background as an author and a journalist meant that, by nature, he was a compulsive writer. He kept diaries, logbooks, typed and handwritten notes and full details of his interests and activities. Most of this information still survives, mainly in the Brotherton Library at the University of Leeds.

Ransome’s time in the Baltic up to 1920 had been fully occupied on journalistic activities and political writings of one sort or another although he was fiercely apolitical. In 1920 he and Evgenia had decided to live in Reval (Tallinn), Estonia, where he spent less time reporting and more time writing in-depth articles for theManchester Guardian.This change of direction in his work activity meant that he was able to enjoy a little more free time to pursue his favourite pastime, fishing. Ransome had sailed a little on Coniston Water, in the Lake District, with his friend Robin Collingwood, son of W.G. Collingwood (the Lakeland poet and writer, a father figure to Ransome after the death of his own father when Arthur was only 13). This introduction to sailing appears to have whetted his appetite for the sport, although in 1920 he considered himself very much a novice. However, he was to learn his skills very quickly.

To set the background forRacundraandRacundra’s First Cruiseit is important that we look briefly at his previous boats:Slugin 1920 andKittiwakein 1921. This period of Ransome’s life has been covered in his autobiography, published in 1976, and in his biography by Hugh Brogan, published in 1984. His early sailing is portrayed somewhat differently in his unpublished notes and writings. In looking at Ransome’s work, shown in American Typewriter font, I have reproduced it exactly as originally written. In the 1920s many of the locations mentioned had different names and I have shown the current names in brackets.

In Peter Hunt’s bookApproaching Arthur Ransome,he criticisesRacundra’s First Cruiseas “a curious volume: it is a specialist work, full of small details of what was a relatively uneventful cruise and many pages of minutiae of sailing and rigging and navigation, which are largely incomprehensible to the layperson.... Ransome leavened the account of sailing inRacundrawith encounters ashore, and possibly because they are padding and not focused on his dominant interest at the time, some are in the worst possible manner – pseudo-symbolic, inconsequential, and rather pretentious. (An example ...The Ship and the Man, first published in theManchester Guardianin 1922).... One of the features ofRacundra’s First Cruiseis that it seems almost a sequel, or a book written for people intimately acquainted not just with sailing, but with Ransome’s life. Old friends, in the form of boats as well as people, continually crop up, scarcely introduced.KittiwakeandSlugare referred to as though we knew them well.”

This was possibly a justified criticism. However, by looking at Ransome’s original material from 1920 and 1921 we can see how he came to include some of his previous experiences inRacundra’s First Cruise.

.

SLUG

Ransome and Evgenia had moved to Reval (Tallinn) in 1919 and, after recovering from a bout of illness (he suffered badly from stomach ulcers all his life), they moved to Lodenzee in Lahepe Bay about 40 miles from Reval (Tallinn). Here they rented rooms in a house with a quiet room where he could write. When shopping in Reval (Tallinn) Ransome always strolled round the harbour looking for something with a mast and sail. He recalls:

(Autobiography) In the end, walking one day along the beach, I came upon a man putting a lick of green paint on a long, shallow boat with a cut-off transom that had once carried an outboard motor. She had a mast. She was for sale. On the beach beside her were large round boulders. I prodded her here and there and asked her price. The man named a sum that sounded enormous in Esthonian marks but when translated into English money came to something under ten pounds. The price included the boulders on the beach.... I bought that boat.... I found Evgenia, told her what I had done and said I would sail the boat from Reval to Lahepe next day. Evgenia, full of quite unjustified faith in me as a mariner, said that she was coming too.

The boat proved so slow that they christened herSlug.His autobiography chronicles in detail the maiden voyage to Lahepe Bay, including his diving overboard for a swim, and the difficulty he had getting back on board when the wind came up andSlugstarted sailing off to Finland with Evgenia in command. He was able with a superhuman effort to get back on board via the bowsprit, a feat that he was never able to repeat. The same trip is portrayed somewhat differently in his typewrittenLog of Slug.He leaves out any mention of the difficulties of returning on board, an episode of which he was no doubt ashamed and wished to forget.

LOG OF THE SLUG

1920

6 a.m. Sunday July 3.

Dead calm. However, we packed our bags and went down to the pier, determined to get out of Reval no matter if only a little way, rather than postpone the start another day. At 6.30, though the water was like glass in the bay, there were occasional catspaws from the northwest. The scoundrel, who came to his pier head to see us off, said he was sure there would be wind of some sort, but the devil only could tell from what quarter. We hoisted sail, and had just enough wind to get us out past the bank of rocks that lies immediately north of the boat piers some few hundred yards from the land. Again dead calm. Thought of bathing from these rocks, but found them surrounded by piles, making approach impossible. Drifted. A very light wind from northwest filled our sail again, and we took a course north northwest. The wind was so slight and we moved so slowly that after tying a bottle to a rope and letting out astern, in case any gust should move her to unexpected hurry, I dived overboard and had a swim. Got on board again, and about seven thirty there was enough wind to give her yard or two of wake. We held on our course, the wind steadily getting a little stronger, till close inshore, north of the mill and south of the wooden pier at Miderando. We were passed by the two masted sailing boat which we had thought of buying the previous day. South of the pier we went about, and with a pleasant but very light wind sailed west northwest making for the southern end of Nargon Island, a run of about eight and half a miles. With great delight we picked up the various buoys marked on our chart, and ran into the little bay southwest of the point, where we grounded the boat, landed, made a fire, and boiled up some cold tea. During the war, landing on Nargon was prohibited, and as we were not sure of our rights, we did not go as we had first intended to the village half a mile away to get milk, but lay low, and did not leave the shore. From where we made tea, we could just see the Surop lighthouse on the Esthonian coast.

SLUG ON REVAL BEACH.

Looking towards Reval, we saw a heavy black sky coming up from the east, and heard thunder. Presently the wind dropped to nothing. Then rose suddenly from the east, and we decided to lose no time, but to run for Surop, and try to get across before the worst of the storm should reach us, as we were on a beach exposed to the east, and could see nothing but rocky coast to the west. We got aboard at 4.30, and took a course southwest for the Surop lighthouse, thinking to shelter from the storm on the western side of Cape Ninamaa. But the storm was upon us before we were two miles on this slant of six. At least, not the storm but the wind. We had only a drop or two of rain, though the whole Esthonian coast east of Surop disappeared altogether in a dark cloud threaded by lightning. The sea turned black and then white in a moment, and the wind fairly lifted our little boat along, so that we were very grateful for the good stone ballast, which our scoundrel friend had stowed in her for the voyage. She stood it beautifully. And we were sorry for a much larger boat, beating up for Reval clear into the storm, which bowed her nearly flat to the water. The wind dropped as suddenly as it rose. The storm blotted out Nargon behind us, and passed, and we sailed slowly by Surop lighthouse, recognising it from our chart, as a white round tower surrounded by trees, at about seven o’clock.

From Cape Ninamaa, we took a course west southwest, hoping to pick up the Pakerort lighthouse about thirteen miles away. But the wind fell almost to nothing. It grew dark. At midnight, sailing, or rather drifting, only for a second or two at a time having any way on the boat, we learnt where we were, when the Pakerort lighthouse glittered out, and finding ourselves on a direct line between it and the Surop, we knew that we were not out of our course. To get home, we had only to round Cape Lohusaar into Lahepe Bay. But once before, fishing for sea-devils, I had been to the mouth of that bay, and knew that isolated rocks run out from Cape Lohusaar a considerable way into the sea. If there had been much wind, we should have run on close to the Pakerort, and then turned back on a southeast slant into the bay, which would have been safe enough. As it was there was not enough wind even to give one control over the boat, so there was nothing to do but to wait till dawn. It was a jolly dawn over the Baltic Sea and, as it lightened, we recognised Lohusaar Cape, only a mile or two before us, and with a slight wind from the southeast sailed past the rocks, which stood out even further than I had remembered across the bay. And then bearing up to the wind which was veering east southeast, cut into and across the bay. It was two in the morning when we were into the bay, and if the wind had held we should have been home to breakfast; but it fell away altogether. We made one interminable tack east northeast and anchored in an almost dead calm, bathed, made a tent out of the mainsail, and fell asleep like logs.

At eleven we woke, and found just enough wind to take us home to the southeast corner of the bay; where, after stripping, and towing her through the narrow channels in the sand banks, we anchored in shallow water, and came ashore, after having had a very good all round specimen of Baltic weather, and gained a very considerable confidence in “The Slug”, besides a little in ourselves.

(Autobiography) It was a ridiculous beginning, to take an open boat for sixty miles of sailing, mostly tacking, along a coast we did not know, but it was not more ridiculous than some of our later experiments. Evgenia had never been in a sailing boat before, and I owe it alike to her ignorance and her courage that this first voyage did not in any way deter her from other adventures. We have never since been without some sort of boat, and for a number of years worked very hard to make ourselves reasonably efficient, taking every chance of sailing in vessels of every kind as well as in our own.

Two days after this eventful first trip Ransome drafted a letter to his old friend Barbara Collingwood (daughter of W.G. Collingwood), with whom he had been in love in his youth. The letter appears not to have been finished or ever sent. It does show, however, that Ransome was at an early stage in developing his sailing skills.

C/O British Consulate,

Reval.

July 5, 1920.

My dear Barbara,

First voyage satisfactorily accomplished. I enclose with this a copy of the Log. The bit with the storm was exciting but short. If it had lasted longer, perhaps we should not have fared so well. As it was it greatly increased the belief I had in the boat and in myself, which, at the beginning, was extremely small. Before starting, we had to get a passport for the boat. They made me put E.P. down as “sailor”. When we were starting, and leaving the pier to which we were tied up, she took an oar and backwatered instead of rowing by mistake, whereupon the scoundrel who sold us the boat remarked with a grin, “Your sailor does not know how to row”. He had already in most uncomplimentary terms expressed his opinion of my own seamanship. I had to work entirely on what I remembered of Robin’s instructions. But one thing he never taught me, and that was how to heave to in a wind and keep more or less in one place without handling the sails. I know the thing is done by fixing the sails and the tiller someway or other, but no amount of rule of thumb experiment arrived at the desired result. I shall be much obliged for detailed instructions, if possible with diagram on this point.

The rig of the boat is not quite the same as Swallow or Jamrach’s. The gaff? (the stick at the top of the mainsail) projected in front of the mast. The boom is as per Swallow. There is also a triangular foresail (?) jib, called hereabouts the cleaver.

That is something like. She is I think 18 feet long. She was built about a hundred years ago, but she practically does not leak at all.

All her rigging is rotten. Ditto her sails, which are made of something suspiciously like old sheets. We’ve spent the day in repairs. In the course of the repairs arose about five hundred technical questions for Robin or Ernest, and neither of these Nesters are on hand. I have with trepidation but apparent success taken out the rope that howks the main sail up, and put it back t’other end on, because it had a knot at one place, which made it impossible to lower it altogether. Further I have developed what seems to me to be rather a shady trick of tying the low corner of the mainsail to the thwart beside the mast. Nothing else to tie it to. A screw with a ring to it probably meant for that purpose came out bodily, suggesting rottenness in the mast, which, for peace of mind, I have to refrain from investigating. E. has patched the mainsail with tablecloth, and talks of grey paint. She says she prefers boats to fishing, and has already learnt to sail the Slug in a calm. I think that unless some accident puts an end to our experiments, another month of Baltic cruising on a minute scale should bring us on a long way in the practical part of the business. But I fairly yearn for Robin, and curse every few minutes the many hours of possible sailing I missed at Coniston. I ought to have tied myself to Swallow, and slept on her, and gone out with her whenever Robin descended from on high to make her perform her mysteries. Then I should know a little more about it. I think I had better number every sentence in this letter, and beg for an expert commentary on each. It’s the little things that I don’t know, how on earth does one make a perfect circle of rope with no knot to fasten round (1) a hollow iron ring and (2) a pulley, by whipping it in the middle? How does one find except by a hundred very wearisome experiments how and where to fasten the rope that howks up the mainsail to the infernally awkward bit of stick that goes across the top of the same instead of ending with jaws round it like the similar stick in good old Swallow?

The Baltic, I may say, has one great advantage over our own in that there is no tide. So if you hit a sandbank with your keel once, you can be sure of hitting it again at any hour of the day. Rocks do not play bo-peep with you. There are hundreds and thousands of them but where they are there they remain, and the wise sailor takes off his hat to them as he passes.

I have got a pretty good German chart of 1908, showing the whole of the gulf of Finland, from Hango in Finland, and the island of Worms (Esthonian) right up to Petrograd, on a scale of what I make out to be about 6¼ miles to the inch. It gives inset charts of the approaches to the principal harbours, on a scale little more than twice as big. It has little miniature pictures of all the lighthouses, so that you can recognise them by day. Enormous fun. I have now made the acquaintance of four of them.

The awful thing about open boat cruising is that one gets absolutely no rest. There is no cabin, no means of sleeping out of the sun, and for grub one has either to land, an unwelcome and risky operation, or else do without a fire and exist on sandwiches. I have absolutely made up my mind to get a boat for single-handed sailing with a cabin, and with everything thought out wilily to make her working easy. Ratchet reefing for example. Everything fixed for comfort so that one could really live on board, which in an open boat like the Slug is impossible. On our thirty-six hour trip, I had only four hours of v. uncomfortable sleep in the bottom of the boat, while at anchor.

Now please, if possible, get answers to some of the questions in this letter... particularly about heaving to. I know that by some trick it is possible to fix up the boat so that she will look after herself, and leave you free, for example to mend a rope, or to eat a meal.

The only known photograph ofSlug,with Evgenia standing on board, was taken on the beach at Reval (Tallinn), shortly after the purchase of the boat. The authenticity of this photograph is born out by the sketch in Ransome’s letter. Photographs attributed toSlugin several publications, including his autobiography (published nine years after his death) are in fact of Ransome’s third boat, the sailing/fishing dinghy, built in Riga, Latvia in late 1921. The description of this boat with a fish box built around the centreboard case gives a positive identification. There was no fish box inSlug.

(Autobiography) I will say no more ofSlug,ill-fated boat. Lahepe Bay was not a very good place in which to keep her afloat. We could reach her only by swimming, and get ashore only by deep wading after bringing her in. We used a raft as a dinghy and it had a bad habit of tipping us sideways into the water.Slugtwice sank at her moorings. Once we left her snugly at anchor and came down to the shore again to find that her mainsail had been stolen.... We had a lot of fun withSlugand the raft, but knew that she was only a makeshift. Our walls were covered with Baltic charts and the plans of boats, and I was able to sweep the worries of writing about Russia out of my head by teaching myself the elements of navigation.

He was so affected by the loss ofSlug’smainsail that he typed an essay on the subject:

Moral Reflections on Theft

There are degrees in robbery. Some thefts are worse than others. I am prepared to forgive natural thefts such as cherry-stealing, in which boys are no worse than chaffinches, and, however they may hurt the pocket, do not grievously offend the moral sense. The theft of money is more sordid, contaminated as it is by the least uplifting of human interests, but it has a practical, sensible character, and can often be justified. It is an evil involved in an imperfect system of distribution. The theft of a fountain pen comes nearer sin. It can never be to the thief the intimate thing that it was to its owner. The gain of the thief is less than the loss occasioned to the owner. The theft of clothes may or may not belong to the some category. The theft of new clothes, if they fit the thief I find easily forgivable, at any rate more easily forgivable than, for example, the abduction of a worn old shooting coat in which every rent and patch is as it were a notch on the tally stick like an entry in the diary of the owner’s life. Horas non numero nisi serenas, is as true of the patches in a shooting coat as of the moving shadow of the sundial. Similarly, I find the theft of a fishing rod far worse than the appropriation of any quantity of mere hooks and similar tackle. The quality of book stealing depends entirely on the personal characters of the thief and the sufferer. I have myself on one on two occasions stolen books, committing crimes for which if there is to be a summing up and general judgment day I confidently hope to be forgiven. And once at least in stealing a book from a man who never read it but owned it merely as a sort of filthy ostentation, I performed an act for which, if there is justice in heaven I expect not forgiveness but reward.

But if the theft of a book may be an act of virtue there are other thefts as black as murder, no; blacker, like the theft of a man’s soul. The theft of a cripple’s wooden leg is a deed whose ugliness will be pretty generally admitted, since, reducing him to immobility, inflicting on him paralysis, it is a particularly vile kind of assault. But even that is not so vile a crime as that which is still ruining the world for me, stopping the cruise of the Slug almost in its auspicious outset. Next to the theft of a man’s soul, I can think of no villainy so utterly abominable as the stealing of the mainsail of a little ship. And that, unthinkable as it must be to any honest man, loathsome to any sailor, actually occurred, on the night between July 7 and 8, in Lahepe Bay, in Esthonia.

Now the mainsail of a little ship is her very soul. Take it away, and you take away the thing that distinguishes her from mere water carriages propelled by oars or steam or petrol. Removing it, you remove the thing that links her with the wind, with the seagulls she resembles. You commit worse than murder. You take the very soul out of her and leave her a dead thing.

It was not a new sail. We had spent the whole of July 6 in patching it with bits of tablecloth. Five laborious patches we had put it. Nor was it a good sail, but made of some inexpensive material, intended, I believe for the underclothing of the Russian army. But, patched and cheap as it was, it was wing enough to lift her through the blue waters of the Baltic Sea, and indeed, like a great wing, towered proudly above her stumpy mast, curving away wing-like to the end of her long boom.