3,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: iOnlineShopping.com

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

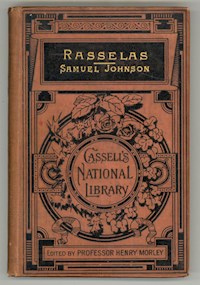

The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia, originally titled The Prince of Abissinia: A Tale, though often abbreviated to Rasselas, is an apologue about happiness by Samuel Johnson. The book's original working title was "The Choice of Life". At the age of fifty, he wrote the piece in only one week to help pay the costs of his mother's funeral, intending to complete it on 22 January 1759 (the eve of his mother's death). The book was first published in April 1759 in England. Johnson is believed to have received a total of £75 for the copyright. The first American edition followed in 1768. The title page of this edition carried a quotation, inserted by the publisher Robert Bell, from La Rochefoucauld: "The labour or Exercise of the Body, freeth Man from the Pains of the Mind; and this constitutes the Happiness of the Poor". While the story is thematically similar to Candide by Voltaire, also published early in 1759 – both concern young men travelling in the company of honoured teachers, encountering and examining human suffering in an attempt to determine the root of happiness – their root concerns are distinctly different. Voltaire was very directly satirising the widely read philosophical work by Gottfried Leibniz, particularly the Theodicee, in which Leibniz asserts that the world, no matter how we may perceive it, is necessarily the "best of all possible worlds". In contrast the question Rasselas confronts most directly is whether or not humanity is essentially capable of attaining happiness. Rasselas questions his choices in life and what new choices to make in order to achieve this happiness. Writing as a devout Christian, Johnson makes through his characters no blanket attacks on the viability of a religious response to this question, as Voltaire does, and while the story is in places light and humorous, it is not a piece of satire, as is Candide. The plot is simple in the extreme, and the characters are flat. Rasselas, son of the King of Abyssinia (modern-day Ethiopia), is shut up in a beautiful valley called The Happy Valley, "till the order of succession should call him to the throne". Rasselas enlists the help of an artist who is also known as an engineer to help with his escape from the Valley by plunging themselves out through the air, though is unsuccessful in this attempt. He grows weary of the factitious entertainments of the place, and after much brooding escapes with his sister Nekayah, her attendant Pekuah and his poet-friend Imlac by digging under the wall of the valley. They are to see the world and search for happiness in places such as Cairo and Suez. After some sojourn in Egypt, where they encounter various classes of society and undergo a few mild adventures, they perceive the futility of their search and abruptly return to Abyssinia after none of their hopes for happiness are achieved.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

Samuel Johnson

Table of contents

Rasselas PRINCE OF ABYSSINIA

INTRODUCTION.

CHAPTER I DESCRIPTION OF A PALACE IN A VALLEY.

CHAPTER II THE DISCONTENT OF RASSELAS IN THE HAPPY VALLEY.

CHAPTER III THE WANTS OF HIM THAT WANTS NOTHING.

CHAPTER IV THE PRINCE CONTINUES TO GRIEVE AND MUSE.

CHAPTER V THE PRINCE MEDITATES HIS ESCAPE.

CHAPTER VI A DISSERTATION ON THE ART OF FLYING.

CHAPTER VII THE PRINCE FINDS A MAN OF LEARNING.

CHAPTER VIII THE HISTORY OF IMLAC.

CHAPTER IX THE HISTORY OF IMLAC (continued).

CHAPTER X IMLAC’S HISTORY (continued)—A DISSERTATION UPON POETRY.

CHAPTER XI IMLAC’S NARRATIVE (continued)—A HINT OF PILGRIMAGE.

CHAPTER XII THE STORY OF IMLAC (continued).

CHAPTER XIII RASSELAS DISCOVERS THE MEANS OF ESCAPE.

CHAPTER XIV RASSELAS AND IMLAC RECEIVE AN UNEXPECTED VISIT.

CHAPTER XV THE PRINCE AND PRINCESS LEAVE THE VALLEY, AND SEE MANY WONDERS.

CHAPTER XVI THEY ENTER CAIRO, AND FIND EVERY MAN HAPPY.

CHAPTER XVII THE PRINCE ASSOCIATES WITH YOUNG MEN OF SPIRIT AND GAIETY.

CHAPTER XVIII THE PRINCE FINDS A WISE AND HAPPY MAN.

CHAPTER XIX A GLIMPSE OF PASTORAL LIFE.

CHAPTER XX THE DANGER OF PROSPERITY.

CHAPTER XXI THE HAPPINESS OF SOLITUDE—THE HERMIT’S HISTORY.

CHAPTER XXII THE HAPPINESS OF A LIFE LED ACCORDING TO NATURE.

CHAPTER XXIII THE PRINCE AND HIS SISTER DIVIDE BETWEEN THEM THE WORK OF OBSERVATION.

CHAPTER XXIV THE PRINCE EXAMINES THE HAPPINESS OF HIGH STATIONS.

CHAPTER XXV THE PRINCESS PURSUES HER INQUIRY WITH MORE DILIGENCE THAN SUCCESS.

CHAPTER XXVI THE PRINCESS CONTINUES HER REMARKS UPON PRIVATE LIFE.

CHAPTER XXVII DISQUISITION UPON GREATNESS.

CHAPTER XXVIII RASSELAS AND NEKAYAH CONTINUE THEIR CONVERSATION.

CHAPTER XXIX THE DEBATE ON MARRIAGE (continued).

CHAPTER XXX IMLAC ENTERS, AND CHANGES THE CONVERSATION.

CHAPTER XXXI THEY VISIT THE PYRAMIDS.

CHAPTER XXXII THEY ENTER THE PYRAMID.

CHAPTER XXXIII THE PRINCESS MEETS WITH AN UNEXPECTED MISFORTUNE.

CHAPTER XXXIV THEY RETURN TO CAIRO WITHOUT PEKUAH.

CHAPTER XXXV THE PRINCESS LANGUISHES FOR WANT OF PEKUAH.

CHAPTER XXXVI PEKUAH IS STILL REMEMBERED. THE PROGRESS OF SORROW.

CHAPTER XXXVII THE PRINCESS HEARS NEWS OF PEKUAH.

CHAPTER XXXVIII THE ADVENTURES OF THE LADY PEKUAH.

CHAPTER XXXIX THE ADVENTURES OF PEKUAH (continued).

CHAPTER XL THE HISTORY OF A MAN OF LEARNING.

CHAPTER XLI THE ASTRONOMER DISCOVERS THE CAUSE OF HIS UNEASINESS.

CHAPTER XLII THE OPINION OF THE ASTRONOMER IS EXPLAINED AND JUSTIFIED.

CHAPTER XLIII THE ASTRONOMER LEAVES IMLAC HIS DIRECTIONS.

CHAPTER XLIV THE DANGEROUS PREVALENCE OF IMAGINATION.

CHAPTER XLV THEY DISCOURSE WITH AN OLD MAN.

CHAPTER XLVI THE PRINCESS AND PEKUAH VISIT THE ASTRONOMER.

CHAPTER XLVII THE PRINCE ENTERS, AND BRINGS A NEW TOPIC.

CHAPTER XLVIII IMLAC DISCOURSES ON THE NATURE OF THE SOUL.

CHAPTER XLIX THE CONCLUSION, IN WHICH NOTHING IS CONCLUDED.

This work has been selected by scholars as being culturally important, and is part of the knowledge base of civilization as we know it. This work was reproduced from the original artifact, and remains as true to the original work as possible. Therefore, you will see the original copyright references, library stamps (as most of these works have been housed in our most important libraries around the world), and other notations in the work.

This work is in the public domain in the United States of America, and possibly other nations. Within the United States, you may freely copy and distribute this work, as no entity (individual or corporate) has a copyright on the body of the work. As a reproduction of a historical artifact, this work may contain missing or blurred pages, poor pictures, errant marks, etc. Scholars believe, and we concur, that this work is important enough to be preserved, reproduced, and made generally available to the public. We appreciate your support of the preservation process, and thank you for being an important part of keeping this knowledge alive and relevant.

About the Publisher - iOnlineShopping.com :

As a publisher, we focus on the preservation of historical literature. Many works of historical writers and scientists are available today as antiques only. iOnlineShopping.com newly publishes these books and contributes to the preservation of literature which has become rare and historical knowledge for the future.

You may buy more interesting and rare books online at https://iOnlineShopping.com

Rasselas PRINCE OF ABYSSINIA

RasselasPRINCE OF ABYSSINIA

BY

SAMUEL JOHNSON, LL.D.

CASSELL & COMPANY, Limited: LONDON, PARIS & MELBOURNE. 1889.

INTRODUCTION.

Rasselas was written by Samuel Johnson in the year 1759, when his age was fifty. He had written his London in 1738; his Vanity of Human Wishes in 1740; his Rambler between March, 1750, and March, 1752. In 1755 his Dictionary had appeared, and Dublin, by giving him its honorary LL.D., had enabled his friends to call him “Doctor” Johnson. His friends were many, and his honour among men was great. He owed them to his union of intellectual power with unflinching probity. But he had worked hard, battling against the wolf without, and the black dog within—poverty and hypochondria. He was still poor, though his personal wants did not exceed a hundred pounds a year. His wife had been seven years dead, and he missed her sorely. His old mother, who lived to the age of ninety, died poor in January of this year, 1759. In her old age, Johnson had sought to help her from his earnings. At her death there were some little debts, and there were costs of burial. That he might earn enough to pay them he wrote Rasselas.

Rasselas was written in the evenings of one week, and sent to press while being written. Johnson earned by it a hundred pounds, with twenty-five pounds more for a second edition. It was published in March or April; Johnson never read it after it had been published until more than twenty years afterwards. Then, finding it in a chaise with Boswell, he took it up and read it eagerly.

This is one of Johnson’s letters to his mother, written after he knew that her last illness had come upon her. It is dated about ten days before her death. The “Miss” referred to in it was a faithful friend. “Miss” was his home name for an affectionate step-daughter, Lucy Porter:—

“ Honoured Madam,—

“The account which Miss gives me of your health pierces my heart. God comfort and preserve you, and save you, for the sake of Jesus Christ.

“I would have Miss read to you from time to time the Passion of our Saviour; and sometimes the sentences in the Communion Service beginning—’Come unto me, all ye that travail and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest.’

“I have just now read a physical book which inclines me to think that a strong infusion of the bark would do you good. Do, dear mother, try it.

“Pray, send me your blessing, and forgive all that I have done amiss to you. And whatever you would have done, and what debts you would have paid first, or anything else that you would direct, let Miss put it down; I shall endeavour to obey you.

“I have got twelve guineas to send you” [six were borrowed. There was a note in Johnson’s Diary of six guineas repaid to Allen, the printer, who had lent them when he wanted to send money to his dying mother], “but unhappily am at a loss how to send it to-night. If I cannot send it to-night, it will come by the next post.

“Pray, do not omit anything mentioned in this letter. God bless you for ever and ever.

“I am, “Your dutiful Son, “ Sam. Johnson.

“ Jan. 13, 1759.”

That is the personal side of the tale of Rasselas. In that way Johnson suddenly, on urgent pressure, carried out a design that had been in his mind. The success of Eastern tales, written as a form of moral essay, in the Rambler and Adventurer, upon suggestion, no doubt, of Addison’s Vision of Mirza, had prompted him to express his view of life more fully than in essay form by way of Oriental apologue; and his early work on Father Lobo’s Voyage to Abyssinia, caused him to choose Abyssinia for the land in which to lay his fable.

But Johnson’s Rasselas has also a close relation to the time when it was written, as Johnson himself had to the time in which he lived. From the beginning of the century—and especially, in England, since the beginning of the reign of George the Second—there had been a growing sense of the ills of life, associated in some minds with doubt whether there could be a just God ruling this unhappy world. Hard problems of humanity pressed more and more on earnest minds. The feeling expressed in Johnson’s Vanity of HumanWishes had deepened everywhere by the year 1759. This has intense expression in Rasselas, where all the joys of life, without active use of the energies of life, can give no joy; and where all uses of the energies of men are for the attainment of ideals worthless or delusive. This life was to Johnson, and to almost all the earnest thinkers of his time, unhappy in itself—a school-house where the rod was ever active. But in its unhappiness Johnson found no power that could overthrow his faith. To him this world was but a place of education for the happiness that would be to the faithful in the world to come. There was a great dread for him in the question, Who shall be found faithful? But there was no doubt in his mind that the happiness of man is to be found only beyond the grave. This was a feeling spread through Europe in the darkness gathering before the outburst of the storm of the great French Revolution. Even Gray, in his Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College, regarded Eton boys at their sports as “little victims,” unconscious of the doom of miseries awaiting them in life. Thus Johnson’s Rasselas is a book doubly typical. We have in it the spirit of the writer when it best expressed the spirit of his time.

H. M.

CHAPTER I DESCRIPTION OF A PALACE IN A VALLEY.

CHAPTER I DESCRIPTION OF A PALACE IN A VALLEY.

Ye who listen with credulity to the whispers of fancy, and pursue with eagerness the phantoms of hope; who expect that age will perform the promises of youth, and that the deficiencies of the present day will be supplied by the morrow, attend to the history of Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia.

Rasselas was the fourth son of the mighty Emperor in whose dominions the father of waters begins his course—whose bounty pours down the streams of plenty, and scatters over the world the harvests of Egypt.

According to the custom which has descended from age to age among the monarchs of the torrid zone, Rasselas was confined in a private palace, with the other sons and daughters of Abyssinian royalty, till the order of succession should call him to the throne.

The place which the wisdom or policy of antiquity had destined for the residence of the Abyssinian princes was a spacious valley in the kingdom of Amhara, surrounded on every side by mountains, of which the summits overhang the middle part. The only passage by which it could be entered was a cavern that passed under a rock, of which it had long been disputed whether it was the work of nature or of human industry. The outlet of the cavern was concealed by a thick wood, and the mouth which opened into the valley was closed with gates of iron, forged by the artificers of ancient days, so massive that no man, without the help of engines, could open or shut them.

From the mountains on every side rivulets descended that filled all the valley with verdure and fertility, and formed a lake in the middle, inhabited by fish of every species, and frequented by every fowl whom nature has taught to dip the wing in water. This lake discharged its superfluities by a stream, which entered a dark cleft of the mountain on the northern side, and fell with dreadful noise from precipice to precipice till it was heard no more.

The sides of the mountains were covered with trees, the banks of the brooks were diversified with flowers; every blast shook spices from the rocks, and every month dropped fruits upon the ground. All animals that bite the grass or browse the shrubs, whether wild or tame, wandered in this extensive circuit, secured from beasts of prey by the mountains which confined them. On one part were flocks and herds feeding in the pastures, on another all the beasts of chase frisking in the lawns, the sprightly kid was bounding on the rocks, the subtle monkey frolicking in the trees, and the solemn elephant reposing in the shade. All the diversities of the world were brought together, the blessings of nature were collected, and its evils extracted and excluded.

The valley, wide and fruitful, supplied its inhabitants with all the necessaries of life, and all delights and superfluities were added at the annual visit which the Emperor paid his children, when the iron gate was opened to the sound of music, and during eight days every one that resided in the valley was required to propose whatever might contribute to make seclusion pleasant, to fill up the vacancies of attention, and lessen the tediousness of time. Every desire was immediately granted. All the artificers of pleasure were called to gladden the festivity; the musicians exerted the power of harmony, and the dancers showed their activity before the princes, in hopes that they should pass their lives in blissful captivity, to which those only were admitted whose performance was thought able to add novelty to luxury. Such was the appearance of security and delight which this retirement afforded, that they to whom it was new always desired that it might be perpetual; and as those on whom the iron gate had once closed were never suffered to return, the effect of longer experience could not be known. Thus every year produced new scenes of delight, and new competitors for imprisonment.

The palace stood on an eminence, raised about thirty paces above the surface of the lake. It was divided into many squares or courts, built with greater or less magnificence according to the rank of those for whom they were designed. The roofs were turned into arches of massive stone, joined by a cement that grew harder by time, and the building stood from century to century, deriding the solstitial rains and equinoctial hurricanes, without need of reparation.

This house, which was so large as to be fully known to none but some ancient officers, who successively inherited the secrets of the place, was built as if Suspicion herself had dictated the plan. To every room there was an open and secret passage; every square had a communication with the rest, either from the upper storeys by private galleries, or by subterraneous passages from the lower apartments. Many of the columns had unsuspected cavities, in which a long race of monarchs had deposited their treasures. They then closed up the opening with marble, which was never to be removed but in the utmost exigences of the kingdom, and recorded their accumulations in a book, which was itself concealed in a tower, not entered but by the Emperor, attended by the prince who stood next in succession.

CHAPTER II THE DISCONTENT OF RASSELAS IN THE HAPPY VALLEY.

CHAPTER II THE DISCONTENT OF RASSELAS IN THE HAPPY VALLEY.

Here the sons and daughters of Abyssinia lived only to know the soft vicissitudes of pleasure and repose, attended by all that were skilful to delight, and gratified with whatever the senses can enjoy. They wandered in gardens of fragrance, and slept in the fortresses of security. Every art was practised to make them pleased with their own condition. The sages who instructed them told them of nothing but the miseries of public life, and described all beyond the mountains as regions of calamity, where discord was always racing, and where man preyed upon man. To heighten their opinion of their own felicity, they were daily entertained with songs, the subject of which was the Happy Valley. Their appetites were excited by frequent enumerations of different enjoyments, and revelry and merriment were the business of every hour, from the dawn of morning to the close of the evening.