Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Phoemixx Classics Ebooks

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

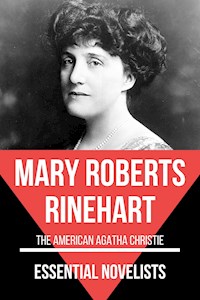

The After House Mary Roberts Rinehart - "An astonishing story of love and mystery, which equals if not surpasses in interest those other lively stories of Mrs. Rinehart's. The novel is one of the sprightliest of the season and will add to the author's reputation as an inventor of 'queer' plots.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 240

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PUBLISHER NOTES:

Quality of Life, Freedom, More time with the ones you Love.

Visit our website: LYFREEDOM.COM

Chapter

1

I PLAN A VOYAGE

By the bequest of an elder brother, I was left enough money to see me through a small college in Ohio, and to secure me four years in a medical school in the East. Why I chose medicine I hardly know. Possibly the career of a surgeon attracted the adventurous element in me. Perhaps, coming of a family of doctors, I merely followed the line of least resistance. It may be, indirectly but inevitably, that I might be on the yacht Ella on that terrible night of August 12, more than a year ago.

I got through somehow. I played quarterback on the football team, and made some money coaching. In summer I did whatever came to hand, from chartering a sail-boat at a summer resort and taking passengers, at so much a head, to checking up cucumbers in Indiana for a Western pickle house.

I was practically alone. Commencement left me with a diploma, a new dress-suit, an out-of-date medical library, a box of surgical instruments of the same date as the books, and an incipient case of typhoid fever.

I was twenty-four, six feet tall, and forty inches around the chest. Also, I had lived clean, and worked and played hard. I got over the fever finally, pretty much all bone and appetite; but—alive. Thanks to the college, my hospital care had cost nothing. It was a good thing: I had just seven dollars in the world.

The yacht Ella lay in the river not far from my hospital windows. She was not a yacht when I first saw her, nor at any time, technically, unless I use the word in the broad sense of a pleasure-boat. She was a two-master, and, when I saw her first, as dirty and disreputable as are most coasting-vessels. Her rejuvenation was the history of my convalescence. On the day she stood forth in her first coat of white paint, I exchanged my dressing-gown for clothing that, however loosely it hung, was still clothing. Her new sails marked my promotion to beefsteak, her brass rails and awnings my first independent excursion up and down the corridor outside my door, and, incidentally, my return to a collar and tie.

The river shipping appealed to me, to my imagination, clean washed by my illness and ready as a child's for new impressions: liners gliding down to the bay and the open sea; shrewish, scolding tugs; dirty but picturesque tramps. My enthusiasm amused the nurses, whose ideas of adventure consisted of little jaunts of exploration into the abdominal cavity, and whose aseptic minds revolted at the sight of dirty sails.

One day I pointed out to one of them an old schooner, red and brown, with patched canvas spread, moving swiftly down the river before a stiff breeze.

"Look at her!" I exclaimed. "There goes adventure, mystery, romance! I should like to be sailing on her."

"You would have to boil the drinking-water," she replied dryly. "And the ship is probably swarming with rats."

"Rats," I affirmed, "add to the local color. Ships are their native habitat. Only sinking ships don't have them."

But her answer was to retort that rats carried bubonic plague, and to exit, carrying the sugar-bowl. I was ravenous, as are all convalescent typhoids, and one of the ways in which I eked out my still slender diet was by robbing the sugar-bowl at meals.

That day, I think it was, the deck furniture was put out on the Ella—numbers of white wicker chairs and tables, with bright cushions to match the awnings. I had a pair of ancient opera-glasses, as obsolete as my amputating knives, and, like them, a part of my heritage. By that time I felt a proprietary interest in the Ella, and through my glasses, carefully focused with a pair of scissors, watched the arrangement of the deck furnishings. A girl was directing the men. I judged, from the poise with which she carried herself, that she was attractive—and knew it. How beautiful she was, and how well she knew it, I was to find out before long. McWhirter to the contrary, she had nothing to do with my decision to sign as a sailor on the Ella.

One of the bright spots of that long hot summer was McWhirter. We had graduated together in June, and in October he was to enter a hospital in Buffalo as a resident. But he was as indigent as I, and from June to October is four months.

"Four months," he said to me. "Even at two meals a day, boy, that's something over two hundred and forty. And I can eat four times a day, without a struggle! Wouldn't you think one of these overworked-for-the-good-of-humanity dubs would take a vacation and give me a chance to hold down his practice?"

Nothing of the sort developing, McWhirter went into a drug-store, and managed to pull through the summer with unimpaired cheerfulness, confiding to me that he secured his luncheons free at the soda counter. He came frequently to see me, bringing always a pocketful of chewing gum, which he assured me was excellent to allay the gnawings of hunger, and later, as my condition warranted it, small bags of gum-drops and other pharmacy confections.

McWhirter it was who got me my berth on the Ella. It must have been about the 20th of July, for the Ella sailed on the 28th. I was strong enough to leave the hospital, but not yet physically able for any prolonged exertion. McWhirter, who was short and stout, had been alternately flirting with the nurse, as she moved in and out preparing my room for the night, and sizing me up through narrowed eyes.

"No," he said, evidently following a private line of thought; "you don't belong behind a counter, Leslie. I'm darned if I think you belong in the medical profession, either. The British army'd suit you."

"The—what?"

"You know—Kipling idea—riding horseback, head of a column—undress uniform—colonel's wife making eyes at you—leading last hopes and all that."

"The British army with Kipling trimmings being out of the question, the original issue is still before us. I'll have to work, Mac, and work like the devil, if I'm to feed myself."

There being no answer to this, McWhirter contented himself with eyeing me.

"I'm thinking," I said, "of going to Europe. The sea is calling me, Mac."

"So was the grave a month ago, but it didn't get you. Don't be an ass, boy. How are you going to sea?"

"Before the mast." This apparently conveying no meaning to McWhirter, I supplemented—"as a common sailor."

He was indignant at first, offering me his room and a part of his small salary until I got my strength; then he became dubious; and finally, so well did I paint my picture of long, idle days on the ocean, of sweet, cool nights under the stars, with breezes that purred through the sails, rocking the ship to slumber—finally he waxed enthusiastic, and was even for giving up the pharmacy at once and sailing with me.

He had been fitting out the storeroom of a sailing-yacht with drugs, he informed me, and doing it under the personal direction of the owner's wife.

"I've made a hit with her," he confided. "Since she's learned I'm a graduate M.D., she's letting me do the whole thing. I've made up some lotions to prevent sunburn, and that seasick prescription of old Larimer's, and she thinks I'm the whole cheese. I'll suggest you as ships doctor."

"How many men in the crew?"

"Eight, I think, or ten. It's a small boat, and carries a small crew."

"Then they don't want a ship's doctor. If I go, I'll go as a sailor," I said firmly. "And I want your word, Mac, not a word about me, except that I am honest."

"You'll have to wash decks, probably."

"I am filled with a wild longing to wash decks," I asserted, smiling at his disturbed face. "I should probably also have to polish brass. There's a great deal of brass on the boat."

"How do you know that?"

When I told him, he was much excited, and, although it was dark and the Ella consisted of three lights, he insisted on the opera-glasses, and was persuaded he saw her. Finally he put down the glasses and came over, to me.

"Perhaps you are right, Leslie," he said soberly. "You don't want charity, any more than they want a ship's doctor. Wherever you go and whatever you do, whether you're swabbing decks in your bare feet or polishing brass railings with an old sock, you're a man."

He was more moved than I had ever seen him, and ate a gum-drop to cover his embarrassment. Soon after that he took his departure, and the following day he telephoned to say that, if the sea was still calling me, he could get a note to the captain recommending me. I asked him to get the note.

Good old Mac! The sea was calling me, true enough, but only dire necessity was driving me to ship before the mast—necessity and perhaps what, for want of a better name, we call destiny. For what is fate but inevitable law, inevitable consequence.

The stirring of my blood, generations removed from a seafaring ancestor; my illness, not a cause, but a result; McWhirter, filling prescriptions behind the glass screen of a pharmacy, and fitting out, in porcelain jars, the medicine-closet of the Ella; Turner and his wife, Schwartz, the mulatto Tom, Singleton, and Elsa Lee; all thrown together, a hodge-podge of characters, motives, passions, and hereditary tendencies, through an inevitable law working together toward that terrible night of August 22, when hell seemed loose on a painted sea.

Chapter

2

THE PAINTED SHIP

The Ella had been a coasting-vessel, carrying dressed lumber to South America, and on her return trip bringing a miscellaneous cargo—hides and wool, sugar from Pernambuco, whatever offered. The firm of Turner and Sons owned the line of which the Ella was one of the smallest vessels.

The gradual elimination of sailing ships and the substitution of steamers in the coasting trade, left the Ella, with others, out of commission. She was still seaworthy, rather fast, as such vessels go, and steady. Marshall Turner, the oldest son of old Elias Turner, the founder of the business, bought it in at a nominal sum, with the intention of using it as a private yacht. And, since it was a superstition of the house never to change the name of one of its vessels, the schooner Ella, odorous of fresh lumber or raw rubber, as the case might be, dingy gray in color, with slovenly decks on which lines of seamen's clothing were generally hanging to dry, remained, in her metamorphosis, still the Ella.

Marshall Turner was a wealthy man, but he equipped his new pleasure-boat very modestly. As few changes as were possible were made. He increased the size of the forward house, adding quarters for the captain and the two mates, and thus kept the after house for himself and his friends. He fumigated the hold and the forecastle—a precaution that kept all the crew coughing for two days, and drove them out of the odor of formaldehyde to the deck to sleep. He installed an electric lighting and refrigerating plant, put a bath in the forecastle, to the bewilderment of the men, who were inclined to think it a reflection on their habits, and almost entirely rebuilt, inside, the old officers' quarters in the after house.

The wheel, replaced by a new one, white and gilt, remained in its old position behind the after house, the steersman standing on a raised iron grating above the wash of the deck. Thus from the chart-room, which had become a sort of lounge and card-room, through a small barred window it was possible to see the man at the wheel, who, in his turn, commanded a view of part of the chartroom, but not of the floor.

The craft was schooner-rigged, carried three lifeboats and a collapsible raft, and was navigated by a captain, first and second mates, and a crew of six able-bodied sailors and one gaunt youth whose sole knowledge of navigation had been gained on an Atlantic City catboat. Her destination was vague—Panama perhaps, possibly a South American port, depending on the weather and the whim of the owner.

I do not recall that I performed the nautical rite of signing articles. Armed with the note McWhirter had secured for me, and with what I fondly hoped was the rolling gait of the seafaring man, I approached the captain—a bearded and florid individual. I had dressed the part—old trousers, a cap, and a sweater from which I had removed my college letter, McWhirter, who had supervised my preparations, and who had accompanied me to the wharf, had suggested that I omit my morning shave. The result was, as I look back, a lean and cadaverous six-foot youth, with the hospital pallor still on him, his chin covered with a day's beard, his hair cropped short, and a cannibalistic gleam in his eyes. I remember that my wrists, thin and bony, annoyed me, and that the girl I had seen through the opera-glasses came on board, and stood off, detached and indifferent, but with her eyes on me, while the captain read my letter.

When he finished, he held it out to me.

"I've got my crew," he said curtly.

"There isn't—I suppose there's no chance of your needing another hand?"

"No." He turned away, then glanced back at the letter I was still holding, rather dazed. "You can leave your name and address with the mate over there. If anything turns up he'll let you know."

My address! The hospital?

I folded the useless letter and thrust it into my pocket. The captain had gone forward, and the girl with the cool eyes was leaning against the rail, watching me.

"You are the man Mr. McWhirter has been looking after, aren't you?"

"Yes." I pulled off my cap, and, recollecting myself—"Yes, miss."

"You are not a sailor?"

"I have had some experience—and I am willing."

"You have been ill, haven't you?"

"Yes—miss."

"Could you polish brass, and things like that?"

"I could try. My arms are strong enough. It is only when I walk—"

But she did not let me finish. She left the rail abruptly, and disappeared down the companionway into the after house. I waited uncertainly. The captain saw me still loitering, and scowled. A procession of men with trunks jostled me; a colored man, evidently a butler, ordered me out of his way while he carried down into the cabin, with almost reverent care, a basket of wine.

When the girl returned, she came to me, and stood for a moment, looking me over with cool, appraising eyes. I had been right about her appearance: she was charming—or no, hardly charming. She was too aloof for that. But she was beautiful, an Irish type, with blue-gray eyes and almost black hair. The tilt of her head was haughty. Later I came to know that her hauteur was indifference: but at first I was frankly afraid of her, afraid of her cool, mocking eyes and the upward thrust of her chin.

"My brother-in-law is not here," she said after a moment, "but my sister is below in the cabin. She will speak to the captain about you. Where are your things?"

I glanced toward the hospital, where my few worldly possessions, including my dress clothes, my amputating set, and such of my books as I had not been able to sell, were awaiting disposition. "Very near, miss," I said.

"Better bring them at once; we are sailing in the morning." She turned away as if to avoid my thanks, but stopped and came back.

"We are taking you as a sort of extra man," she explained. "You will work with the crew, but it is possible that we will need you—do you know anything about butler's work?"

I hesitated. If I said yes, and then failed—

"I could try."

"I thought, from your appearance, perhaps you had done something of the sort." Oh, shades of my medical forebears, who had bequeathed me, along with the library, what I had hoped was a professional manner! "The butler is a poor sailor. If he fails us, you will take his place."

She gave a curt little nod of dismissal, and I went down the gangplank and along the wharf. I had secured what I went for; my summer was provided for, and I was still seven dollars to the good. I was exultant, but with my exultation was mixed a curious anger at McWhirter, that he had advised me not to shave that morning.

My preparation took little time. Such of my wardrobe as was worth saving, McWhirter took charge of. I sold the remainder of my books, and in a sailor's outfitting-shop I purchased boots and slickers—the sailors' oil skins. With my last money I bought a good revolver, second-hand, and cartridges. I was glad later that I had bought the revolver, and that I had taken with me the surgical instruments, antiquated as they were, which, in their mahogany case, had accompanied my grandfather through the Civil War, and had done, as he was wont to chuckle, as much damage as a three-pounder. McWhirter came to the wharf with me, and looked the Ella over with eyes of proprietorship.

"Pretty snappy-looking boat," he said. "If the nigger gets sick, give him some of my seasick remedy. And take care of yourself, boy." He shook hands, his open face flushed with emotion. "Darned shame to see you going like this. Don't eat too much, and don't fall in love with any of the women. Good-bye."

He started away, and I turned toward the ship; but a moment later I heard him calling me. He came back, rather breathless.

"Up in my neighborhood," he panted, "they say Turner is a devil. Whatever happens, it's not your mix-in. Better—better tuck your gun under your mattress and forget you've got it. You've got some disposition yourself."

The Ella sailed the following day at ten o'clock. She carried nineteen people, of whom five were the Turners and their guests. The cabin was full of flowers and steamer-baskets.

Thirty-one days later she came into port again, a lifeboat covered with canvas trailing at her stern.

Chapter

3

I UNCLENCH MY HANDS

From the first the captain disclaimed responsibility for me. I was housed in the forecastle, and ate with the men. There, however, my connection with the crew and the navigation of the ship ended. Perhaps it was as well, although I resented it at first. I was weaker than I had thought, and dizzy at the mere thought of going aloft.

As a matter of fact, I found myself a sort of deck-steward, given the responsibility of looking after the shuffle-board and other deck games, the steamer-rugs, the cards,—for they played bridge steadily,—and answerable to George Williams, the colored butler, for the various liquors served on deck.

The work was easy, and the situation rather amused me. After an effort or two to bully me, one of which resulted in my holding him over the rail until he turned gray with fright, Williams treated me as an equal, which was gratifying.

The weather was good, the food fair. I had no reason to repent my bargain. Of the sailing qualities of the Ella there could be no question. The crew, selected by Captain Richardson from the best men of the Turner line, knew their business, and, especially after the Williams incident, made me one of themselves. Barring the odor of formaldehyde in the forecastle, which drove me to sleeping on deck for a night or two, everything was going smoothly, at least on the surface.

Smoothly as far as the crew was concerned. I was not so sure about the after house.

As I have said, owing to the small size, of the vessel, and the fact that considerable of the space had been used for baths, there were, besides the family, only two guests, a Mrs. Johns, a divorcee, and a Mr. Vail. Mrs. Turner and Miss Lee shared the services of a maid, Karen Hansen, who, with a stewardess, Henrietta Sloane, occupied a double cabin. Vail had a small room, as had Turner, with a bath between which they used in common. Mrs. Turner's room was a large one, with its own bath, into which Elsa Lee's room also opened. Mrs. Johns had a room and bath. Roughly, and not drawn to scale, the living quarters of the family were arranged like the diagram in chapter XIX.

I have said that things were not going smoothly in the after house. I felt it rather than, saw it. The women rose late—except Miss Lee, who was frequently about when I washed the deck. They chatted and laughed together, read, played bridge when the men were so inclined, and now and then, when their attention was drawn to it, looked at the sea. They were always exquisitely and carefully dressed, and I looked at them as I would at any other masterpieces of creative art, with nothing of covetousness in my admiration.

The men were violently opposed types Turner, tall, heavy-shouldered, morose by habit, with a prominent nose and rapidly thinning hair, and with strong, pale blue eyes, congested from hard drinking; Vail, shorter by three inches, dark, good-looking, with that dusky flush under the skin which shows good red blood, and as temperate as Turner was dissipated.

Vail was strong, too. After I had held Williams over the rail I turned to find him looking on, amused. And when the frightened darky had taken himself, muttering threats, to the galley, Vail came over to me and ran his hand down my arm.

"Where did you get it?" he asked.

"Oh, I've always had some muscle," I said. "I'm in bad shape now; just getting over fever."

"Fever, eh? I thought it was jail. Look here."

He threw out his biceps for me to feel. It was a ball of iron under my fingers. The man was as strong as an ox. He smiled at my surprise, and, after looking to see that no one was in sight, offered to mix me a highball from a decanter and siphon on a table.

I refused.

It was his turn to be surprised.

"I gave it up when I was in train—in the hospital," I corrected myself. "I find I don't miss it."

He eyed me with some curiosity over his glass, and, sauntering away, left me to my work of folding rugs. But when I had finished, and was chalking the deck for shuffle-board, he joined me again, dropping his voice, for the women had come up by that time and were breakfasting on the lee side of the after house.

"Have you any idea, Leslie, how much whiskey there is on board?"

"Williams has considerable, I believe. I don't think there is any in the forward house. The captain is a teetotaler."

"I see. When these decanters go back, Williams takes charge of them?"

"Yes. He locks them away."

He dropped his voice still lower.

"Empty them, Leslie," he said. "Do you understand? Throw what is left overboard. And, if you get a chance at Williams's key, pitch a dozen or two quarts overboard."

"And be put in irons!"

"Not necessarily. I think you understand me. I don't trust Williams. In a week we could have this boat fairly dry."

"There is a great deal of wine."

He scowled. "Damn Williams, anyhow! His instructions were—but never mind about that. Get rid of the whiskey."

Turner coming up the companionway at that moment, Vail left me. I had understood him perfectly. It was common talk in the forecastle that Turner was drinking hard, and that, in fact, the cruise had been arranged by his family in the hope that, away from his clubs; he would alter his habits—a fallacy, of course. Taken away from his customary daily round, given idle days on a summer sea, and aided by Williams, the butler, he was drinking his head off.

Early as it was, he was somewhat the worse for it that morning. He made directly for me. It was the first time he had noticed me, although it was the third day out. He stood in front of me, his red eyes flaming, and, although I am a tall man, he had an inch perhaps the advantage of me.

"What's this about Williams?" he demanded furiously. "What do you mean by a thing like that?"

"He was bullying me. I didn't intend to drop him."

The ship was rolling gently; he made a pass at me with a magazine he carried, and almost lost his balance. The women had risen, and were watching from the corner of the after house. I caught him and steadied him until he could clutch a chair.

"You try any tricks like that again, and you'll go overboard," he stormed. "Who are you, anyhow? Not one of our men?"

I saw the quick look between Vail and Mrs. Turner, and saw her come forward. Mrs. Johns followed her, smiling.

"Marsh!" Mrs. Turner protested. "I told you about him—the man who had been ill."

"Oh, another of your friends!" he sneered, and looked from me to Vail with his ugly smile.

Vail went rather pale and threw up his head quickly. The next moment Mrs. Johns had saved the situation with an irrelevant remark, and the incident was over. They were playing bridge, not without dispute, but at least without insult. But I had hard a glimpse beneath the surface of that luxurious cruise, one of many such in the next few days.

That was on Monday, the third day out. Up to that time Miss Lee had not noticed me, except once, when she found me scrubbing the deck, to comment on a corner that she thought might be cleaner, and another time in the evening, when she and Vail sat in chairs until late, when she had sent me below for a wrap. She looked past me rather than at me, gave me her orders quietly but briefly, and did not even take the trouble to ignore me. And yet, once or twice, I had found her eyes fixed on me with a cool, half-amused expression, as if she found something in my struggles to carry trays as if I had been accustomed to them, or to handle a mop as a mop should be handled and not like a hockey stick—something infinitely entertaining and not a little absurd.

But that morning, after they had settled to bridge, she followed me to the rail, out of earshot I straightened and took off my cap, and she stood looking at me, unsmiling.

"Unclench your hands!" she said.

"I beg your pardon!" I straightened out my fingers, conscious for the first time of my clenched fists, and even opened and closed them once or twice to prove their relaxation.

"That's better. Now—won't you try to remember that I am responsible for your being here, and be careful?"

"Then take me away from here and put me with the crew. I am stronger now. Ask the captain to give me a man's work. This—this is a housemaid's occupation."

"We prefer to have you here," she said coldly; and then, evidently repenting her manner: "We need a man here, Leslie. Better stay. Are you comfortable in the forecastle?"

"Yes, Miss Lee."

"And the food is all right?"

"The cook says I am eating two men's rations."

She turned to leave, smiling. It was the first time she had thrown even a fleeting smile my way, and it went to my head.

"And Williams? I am to submit to his insolence?"

She stopped and turned, and the smile faded.

"The next time," she said, "you are to drop him!"

But during the remainder of the day she neither spoke to me nor looked, as far as I could tell, in my direction. She flirted openly with Vail, rather, I thought, to the discomfort of Mrs. Johns, who had appropriated him to herself—sang to him in the cabin, and in the long hour before dinner, when the others were dressing, walked the deck with him, talking earnestly. They looked well together, and I believe he was in love with her. Poor Vail!

Turner had gone below, grimly good-humored, to dress for dinner; and I went aft to chat, as I often did, with the steersman. On this occasion it happened to be Charlie Jones. Jones was not his name, so far as I know. It was some inordinately long and different German inheritance, and so, with the facility of the average crew, he had been called Jones. He was a benevolent little man, highly religious, and something of a philosopher. And because I could understand German, and even essay it in a limited way, he was fond of me.