0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

When Priscilla Harradine meets buccaneer Charles de Bernis on the ship that's carrying her back to England, the appearance of a notorious pirate puts her safety entirely in the hands of her new acquaintance.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

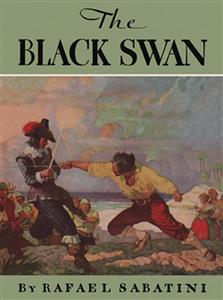

The Black Swan

by Rafael Sabatini

First published in 1932

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Chapter 1. Fortune and Major Sands

Major Sands, conscious of his high deserts, was disposed to receive with condescension the gifts which he perceived that Fortune offered him. She could not bribe him with them into a regard for her discernment. He had seen her shower favours upon the worthless and defraud the meritorious of their just reward. And she had kept him waiting. If at last she turned to him, he supposed that it was less from any gracious sense of justice in herself than because Major Sands had known how to constrain her.

This, from all the evidence I have sifted, I take to have been the complexion of his thoughts as he lounged beside the day-bed set for Miss Priscilla Harradine under the awning of brown sailcloth which had been improvised on the high poop of the Centaur.

The trim yellow ship lay at anchor in the spacious bay of Fort Royal, which she had made her first port of call after the short run from Barbados. They were taking fresh water aboard, and this was providing an occasion to induce them to take other things. In the forechains the Negro steward and the cook were receiving a bombardment of mangled English and smooth French from a cluster of periaguas, laden with fruit and vegetables, that bumped and scraped alongside, manned by whites, half-castes, Negroes and Caribs, all of them vociferous in their eagerness to sell.

At the head of the entrance ladder stood Captain Bransome in a stiff-skirted coat of dark blue with tarnished gold lace, refusing admission to the gabardined and persistent Jew in the cockboat at the foot of it, who was offering him bargains in cocoa, ginger, and spices.

Inshore, across the pellucid jade green waters of the bay, gently ruffled by the north-easterly breeze that was sweetly tempering the torrid heat of the sun, rose the carnage of masts and spars of the shipping riding there at anchor. Beyond this the little town of Fort Royal showed sharply white against the emerald green undulating slopes of Martinique, slopes dominated in the north by the volcanic mass of Mont Pele which thrust its rugged summit into the cobalt sky.

Captain Bransome, his glance alternating between the Jew who would not be dismissed, and a longboat that half a mile away was heading for the ship, removed his round black castor. Under this his head was swathed in a blue cotton handkerchief, as being cooler than a periwig. He stood mopping his brow whilst he waited. He was feeling the heat in the ponderous European finery which, out of regard for the dignity of his office of master, he donned whenever putting into port.

On the poop above, despite the breeze and the shadow of the awning, Major Sands, too, was feeling the heat, inclining as he did to a rather fleshly habit of body, and this despite a protracted sojourn in the Tropic of Cancer. He had come out five years ago whilst King Charles II was still alive. He had volunteered for service overseas in the conviction that in the New World he would find that fortune which eluded him in the Old. The necessity was imposed upon him by a dissolute father who had gamed and drunk the broad family estates in Wiltshire. Major Sands' inheritance, therefore, had been scanty. At least, it did not include--and for this he daily returned thanks to his Maker--the wasteful, improvident proclivities of his sire. The Major was no man for hazards. In contrast with his profligate father, he was of that cold and calculating temperament which, when allied with intelligence, will carry a man far. In Major Sands the intelligence was absent; but like most men in his case he was not aware of it. If he had not realized his hopes strictly in accordance with the expectations that had sent him overseas, he perceived that he was about to realize them very fully, nevertheless. And however unforeseen the circumstances to which the fact was due, this nowise troubled his perception that the achievement proceeded from his own merit and address. Hence his disdainful attitude towards Fortune. The issue, after all, was a simple one. He had come out to the West Indies in quest of fortune. And in the West Indies he had found it. He had achieved what he came to achieve. Could cause and effect be linked more closely?

This fortune which he had won, or the winning of which awaited now his pleasure, reclined on a day-bed of cane and carved oak, and was extremely good to look upon. Slim and straight, clean-limbed and moderately tall, Priscilla Harradine displayed an outward grace of body that was but the reflection of an inner grace of mind. The young face under the shadow of the wide-brimmed hat was of a winning loveliness; it was of that delicate tint that went with the deep golden of her hair, and it offered little evidence of long years spent in the blistering climate of Antigua. If there was spirit in her resolute little chin and firmly modelled lips, there was only tenderness and candour in the eyes, wide-set and intelligent and of a colour that was something between the deep blue of the sky and the jade-green of the sea on which they gazed. She wore a high-waisted gown of ivory-coloured silk, and the escalloped edges of her bodice were finely laced with gold. Languidly she waved a fan, fashioned from the vivid green-and-scarlet of parrots' feathers, in the heart of which a little oval mirror had been set.

Her father, Sir John Harradine, had been actuated by motives similar to those of Major Sands in exiling himself from England to a remote colonial settlement. His fortunes, too, had been at a low ebb; and as much for the sake of his only and motherless child as for his own, he had accepted the position of Captain-General of the Leeward Islands, the offer of which a friend at court had procured for him. Great opportunities of fortune came the way of an alert colonial governor. Sir John had known how to seize them and squeeze them during the six years that his governorship had lasted, and when at last he died--prematurely cut off by a tropical fever--he was in a position to make amends to his daughter for the years of exile she had shared with him, by leaving her mistress of a very substantial fortune and of a very fair estate in his native Kent which a trustworthy agent in England had acquired for him.

It had been Sir John's wish that she should go home at once to this, and to his sister who would guide her. On his deathbed he protested that too much of her youth already had she wasted in the West Indies through his selfishness. For this he begged her pardon, and so died.

They had been constant companions and good friends, she and her father. She missed him sorely, and might have missed him more, might have been dejected by his death into a deeper sense of loneliness, but for the ready friendship, attention, and service of Major Sands.

Bartholomew Sands had acted as the Captain-General's second-in-command. He had lived at Government House with them so long that Miss Priscilla had come to look upon him as one of the family, and was glad enough to lean upon him now. And the Major was even more glad to be leaned cupon. His hopes of succeeding Sir John in the governorship of Antigua were slight. Not that in his view he lacked the ability. He knew that he had ability to spare. But court favour in these matters, he supposed, counted for more than talent or experience; and court favour no doubt would be filling the vacant post with some inept fribble from home.

The perception of this quickened his further perception that his first duty was to Miss Priscilla. He told her so, and overwhelmed the child by this display of what she accounted an altruistic nobility. For she was under the assumption that his natural place was in her father's vacant seat, an assumption which he was far from wishing to dispel. It might well be so, he opined; but it could matter little when weighed against her possible need of him. She would be going home to England now. The voyage was long, tedious, and fraught with many perils. To him it was as inconceivable as it was intolerable that she should take this voyage unaccompanied and unprotected. Even though he should jeopardize his chances of the succession of the governorship as a consequence of leaving the island at such a time, yet his sense of duty to herself and his regard for her left him no choice. Also, he added, with impressive conviction, it was what her father would have wished.

Overbearing her gentle objections to this self-sacrifice, he had given himself leave of absence, and had appointed Captain Grey to the lieutenant-governorship until fresh orders should come from Whitehall.

And so he had shipped himself with her aboard the Centaur, and with her at first had been her black waiting-woman Isabella. Unfortunately, the Negress had suffered so terribly from seasickness that it was impossible to take her across the ocean, and they had been constrained to land her at Barbados, so that henceforth Miss Priscilla must wait upon herself.

Major Sands had chosen the Centaur for her fine roominess and seaworthy qualities despite the fact that before setting a course for home her master had business to transact farther south in Barbados. If anything, the Major actually welcomed this prolongation of the voyage, and consequently of this close and intimate association with Miss Priscilla. It was in his calculating nature to proceed slowly, to spoil nothing by precipitancy. He realized that his wooing of Sir John Harradine's heiress, which, indeed, had not begun until after Sir John's death had cast her, as it were, upon his hands, must be conducted yet some little way before he could account that he had won her. There were certain disadvantages to be overcome, certain possible prejudices to be broken down. After all, although undoubtedly a very personable man--a fact of which his mirror gave him the most confident assurances--there was an undeniable disparity of age between them. Miss Priscilla was not yet twenty-five, whilst Major Sands had already turned his back on forty, and was growing rather bald under his golden periwig. At first he had clearly perceived that she was but too conscious of his years. She had treated him with an almost filial deference, which had brought him some pain and more dismay. With the close association that had been theirs and the suggestive skill with which he had come to establish a sense of approximate coevality, this attitude in her was being gradually dispelled. He looked now to the voyage to enable him to complete the work so well begun. He would be a dolt, indeed, if he could not contrive that this extremely desirable lady and her equally desirable fortune should be contracted to him before they cast anchor in Plymouth Roads. It was upon this that he had staked his slender chances of succession to the governorship of Antigua. But, as I have said, Major Sands was no gambler. And this was no gambler's throw. He knew himself, his personableness, his charms and his arts, well enough, to be confident of the issue. He had merely exchanged a possibility for a certainty; the certainty of that fortune which he had originally come overseas to seek, and which lay now all but within his grasp.

This was his settled conviction as he leaned forward in his chair, leaned nearer to tempt her with the Peruvian sweetmeats in the silver box he proffered, procured for her with that touching anticipation of her every possible wish which by now she must have come to remark in him.

She stirred against the cushion of purple velvet with its gold tassels, which his solicitous hands had fetched from the cabin and placed behind her. She shook her head in refusal, but smiled upon him with a gentleness that was almost tender.

'You are so watchful of my comfort, Major Sands, that it is almost ungracious to refuse anything you bring. But...' She waved her green-and-scarlet fan.

He feigned ill-humour, which may not have been entirely feigned. 'If I am to be Major Sands to you to the end of my days, faith, I'll bring you nothing more. I am called Bartholomew, ma'am. Bartholomew.'

'A fine name,' said she. 'But too fine and long for common everyday use, in such heat as this.'

His answer to that was almost eager. Disregarding her rallying note, he chose to take her literally 'I have been called Bart upon occasion, by my friends. It's what my mother called me always. I make you free of it, Priscilla.'

'I am honoured, Bart,' she laughed, and so rejoiced him.

Four couplets sounded from the ship's belfry. It brought her to sit up as if it had been a signal.

'Eight bells, and we are still at anchor. Captain Bransome said we should be gone before now.' She rose. 'What keeps us here, I wonder.'

As if to seek an answer to her question, she moved from the shadow of the awning. Major Sands, who had risen with her, stepped beside her to the taffrail.

The cockboat with the baffled Jew was already on its way back to the shore. The periaguas were falling away, their occupants still vociferous, chopping wit now with some sailors who leaned upon the bulwarks. But the longboat, which Captain Bransome had been watching, was coming alongside at the foot of the entrance ladder. One of the naked brown Caribs by whom she was manned knelt in the prow to seize a bight of rope and steady her against the vessel's side.

From her stern-sheets rose the tall, slim, vigorous figure of a man in a suit of pale blue taffetas with silver lace. About the wide brim of his black hat curled a pale blue ostrich plume, and the hand he put forth to steady himself upon the ladder was gloved and emerged from a cloud of fine lace.

'Odds life!' quoth Major Sands, in amazement at this modishness off Martinique. 'And who may this be?'

His amazement increased to behold the practised agility with which this modish fellow came swiftly up that awkward ladder. He was followed, more clumsily, by a half-caste in a cotton shirt and breeches of hairy, untanned hide, who carried a cloak, a rapier, and a sling of purple leather, stiff with bullion, from the ends of which protruded the chased silver butts of a brace of pistols.

The newcomer reached the deck. A moment he paused, tall and commanding at the ladder's head; then he stepped down into the waist, and doffed his hat in courteous response to the Captain's similar salutation. He revealed a swarthy countenance below a glossy black periwig that was sedulously curled.

The Captain barked an order. Two of the hands sprang to the main hatch for a canvas sling, and went to lower it from the bulwarks.

By this the watchers on the poop saw first one chest and then another hauled up to the deck.

'He comes to stay, it seems,' said Major Sands.

'He has the air of a person of importance,' ventured Miss Priscilla.

The Major was perversely moved to contradict her. 'You judge by his foppish finery. But externals, my dear, can be deceptive. Look at his servant, if that rascal is his servant. He has the air of a buccaneer.'

'We are in the Indies, Bart,' she reminded him.

'Why, so we are. And somehow this gallant seems out of place in them. I wonder who he is.'

A shrill blast from the bo'sun's whistle was piping the hands to quarters, and the ship suddenly became alive with briskly moving men.

As the creak of windlass and the clatter of chain announced the weighing of the anchor, and the hands went swarming aloft to set the sails, the Major realized that their departure had been delayed because they had waited for this voyager to come aboard. For the second time he vaguely asked of the north-easterly breeze: 'I wonder who the devil he may be?'

His tone was hardly good-humored. It was faintly tinged by the resentment that their privacy as the sole passengers aboard the Centaur should be invaded. This resentment would have been less unreasonable could he have known that this voyager was sent by Fortune to teach Major Sands not to treat her favours lightly.

Chapter 2. Monsieur de Bernis

To say that their curiosity on the subject of the newcomer was gratified in the course of the next hour, when they met him at dinner, would not be merely an overstatement, it would be in utter conflict with the fact. That meeting, which took place in the great cabin, where dinner was served, merely went to excite a deeper curiosity.

He was presented to his two fellow passengers by Captain Bransome as Monsieur Charles de Bernis, from which it transpired that he was French. But the fact was hardly to have been suspected from the smooth fluency of his English, which bore only the faintest trace of a Gallic accent. If his nationality betrayed itself at all, it was only in a certain freedom of gesture, and, to the prominent blue English eyes of Major Sands, in a slightly exaggerated air of courtliness. Major Sands, who had come prepared to dislike him, was glad to discover in the fellow's personality no cause to do otherwise. If there had been nothing else against the man, his foreign origin would have been more than enough; for Major Sands had a lofty disdain for all those who did not share his own good fortune of having been born a Briton.

Monsieur de Bernis was very tall, and if spare he yet conveyed a sense of toughness. The lean leg in its creaseless pale blue stocking looked as if made of whipcord. He was very swarthy, and bore, as Major Sands perceived at once, a curious likeness to his late Majesty King Charles II in his younger days; for the Frenchman could be scarcely more than thirty-five. He had the same hatchet face with its prominent cheek-bones, the same jutting chin and nose, the same tiny black moustache above full lips about which hovered the same faintly sardonic expression that had marked the countenance of the Stuart sovereign. Under intensely black brows his eyes were dark and large, and although normally soft and velvety, they could, as he soon revealed, by a blazing directness of glance, be extremely disconcerting.

If his fellow passengers were interested in him, it could hardly be said that he returned the compliment at first. The very quality of his courtesy towards them seemed in itself to raise a barrier beyond which he held aloof. His air was preoccupied, and such concern as his conversation manifested whilst they ate was directed to the matter of his destination.

In this he seemed to be resuming an earlier discussion between himself and the master of the Centaur.

'Even if you will not put in at Mariegalante, Captain, I cannot perceive that it could delay or inconvenience you to send me ashore in a boat.'

'That's because ye don't understand my reasons,' said Bransome. 'I've no mind to sail within ten miles o' Guadeloupe. If trouble comes my way, faith, I can deal with it. But I'm not seeking it. This is my last voyage, and I want it safe and peaceful. I've a wife and four children at home in Devon, and it's time I were seeing something of them. So I'm giving a wide berth to a pirate's nest like Guadeloupe. It's bad enough to be taking you to Sainte Croix.'

'Oh, that...' The Frenchman smiled and waved a long brown hand, tossing back the fine Mechlin from his wrist.

But Bransome frowned at the deprecatory gesture. 'Ye may smile, Mossoo. Ye may smile. But I know what I knows. Your French West India Company ain't above suspicion. All they asks is a bargain, and they don't care how they come by it. There's many a freight goes into Sainte Croix to be sold there for a tenth of its value. The French West India Company asks no questions, so long as it can deal on such terms as they And it don't need to ask no questions. The truth's plain enough. It shrieks. And that's the fact. Maybe ye didn't know it.'

The Captain, a man in middle life, broad and powerful, ruddy of hair and complexion, lent emphasis to his statement and colour to the annoyance it stirred in him by bringing down on the table a massive freckled hand on which the red hairs gleamed like fire.

'Sainte Croix since I've undertaken to carry you there. And that's bad enough, as I say. But no Guadeloupe for me.'

Mistress Priscilla stirred in her seat. She leaned forward. 'Do you speak of pirates, Captain Bransome?'

'Aye!' said Bransome. 'And that's the fact.'

Conceiving her alarmed, the Major entered the discussion with the object of reassuring her.

'Faith, it's not a fact to be mentioned before a lady. And anyway, it's a fact for the timorous only nowadays.'

'Oho!' Vehemently Captain Bransome blew out his cheekss.

'Buccaneers,' said Major Sands, 'are things of the past.'

The Captain's face was seen to turn a deeper red. His contradiction took the form of elaborate sarcasm. 'To be sure, it's as safe cruising in the Caribbean today as on any of the English lakes.'

After that he gave his attention to his dinner, whilst Major Sands addressed himself to Monsieur de Bernis.

'You go with us, then, no farther than Sainte Croix?' His manner was more pleasant than it had yet been, for his good-humour was being restored by the discovery that this intrusion was to be only a short one.

'No farther,' said Monsieur de Bernis.

The laconic answer did not encourage questions. Nevertheless Major Sands persisted.

'You will have interests in Sainte Croix?'

'No interests. No. I seek a ship. A ship to take me to France.' It was characteristic of him to speak in short, sharp sentences.

The Major was puzzled. 'But, surely, being aboard so fine a ship as this, you might travel comfortably to Plymouth, and there find a sloop to put you across the Channel.'

'True,' said Monsieur de Bernis. 'True! I had not thought of it.'

The Major was conscious of a sudden apprehension that he might have said too much. To his dismay he heard Miss Priscilla voicing the idea which he feared he might have given to the Frenchman.

'You will think of it now, monsieur?'

Monsieur de Bernis' dark eyes glowed as they rested upon her; but his smile was wistful.

'By my faith, mademoiselle, you must compel a man to do so.'

Major Sands sniffed audibly at what he accounted an expression of irrepressible impudent Gallic gallantry. Then, after a slight pause, Monsieur de Bernis added with a deepening of his wistful smile:

'But, alas! A friend awaits me in Sainte Croix. I am to cross with him to France.'

The Major interposed, a mild astonishment in his voice.

'I thought it was at Guadeloupe that you desired to be put ashore, and that your going to Sainte Croix was forced upon you by the Captain.'

If he thought to discompose Monsieur de Bernis by confronting him with this contradiction, he was soon disillusioned. The Frenchman turned to him slowly still smiling, but the wistfulness had given place to a contemptuous amusement.

'But why unveil the innocent deception which courtesy to a lady thrust upon me? It is more shrewd than kind, Major Sands.'

Major Sands flushed. He writhed under the Frenchman's superior smile, and in his discomfort blundered grossly.

'What need for deceptions, sir?'

'Add, too: what need for courtesy? Each to his nature, sir. You convict me of a polite deceit, and discover yourself to be of a rude candour. Each of us in his different way is admirable.'

'That is something to which I can't agree at all. Stab me if I can.'

'Let mademoiselle pronounce between us, then,' the Frenchman smilingly invited.

But Miss Priscilla shook her golden head. 'That would be to pronounce against one of you. Too invidious a task.'

'Forgive me, then, for venturing to set it. Well leave the matter undecided.' He turned to Captain Bransome, 'You said, I think, Captain, that you are calling at Dominica.' Thus he turned the conversation into different channels.

The Major was left with an uncomfortable sense of being diminished. It rankled in him, and found expression later when with Miss Priscilla he was once more upon the poop.

'I do not think the Frenchman was pleased at being put down,' said he.

At table the Major's scarcely veiled hostility to the stranger had offended her sense of fitness. In her eyes he had compared badly with the suave and easy Frenchman. His present smugness revived her irritation.

'Was he put down?' said she. 'I did not observe it.'

'You did not...' The prominent pale eyes seemed to swell in his florid face. Then he laughed boisterously. 'You were day-dreaming, Priscilla, surely. You cannot have attended. I let him see plainly that I was not to be hoodwinked by his contradictions. I'm never slow to perceive deceit. It annoyed him to be so easily exposed.'

'He dissembled his annoyance very creditably.'

'Oh, aye! As a dissembler I give him full credit. But I could see that I had touched him. Stab me, I could. D'ye perceive the extent of his dissimulation? First it was only that he had not thought of crossing the ocean in the Centaur. Then it was that he has a friend awaiting him in Sainte Croix, and I, knowing all the while that Sainte Croix was forced upon him by the Captain who could not be persuaded to land him, as he wished, at Guadeloupe. I wonder what the fellow has to hide that he should be so desperately clumsy?'

'Whatever it is, it can be no affair of ours.'

'You make too sure, perhaps. After all, I am an officer of the Crown, and it's scarcely less than my duty to be aware of all that happens in these waters.'

'Why plague yourself? In a day or two he will have left us again.'

'To be sure. And I thank God for 't.'

'I see little cause for thanksgiving. Monsieur de Bernis should prove a lively companion on a voyage.'

The Major's brows were raised. 'You conceive him lively?'

'Did not you? Was there no wit in his parries when you engaged him?'

'Wit! Lord! I thought him as clumsy a bar as I have met.'

A black hat embellished by a sweeping plume of blue appeared above the break of the quarter-deck. Monsieur de Bernis was ascending the companion. He came to join them on the poop.

The Major was disposed to regard his advent as an unbidden intrusion. But Miss Priscilla's eyes gleamed a welcome to the courtly Frenchman; and when she moved aside invitingly to the head of the day-bed, so as to make room for him to sit beside her, Major Sands must mask his vexation as best he could in chill civilities.

Martinique by now was falling hazily astern, and the Centaur under a full spread of canvas was beating to westward with a larboard list that gently canted her yellow deck.

Monsieur de Bernis commended the north-easterly breeze in terms of one familiar with such matters. They were fortunate in it, he opined. At this season of the year, the prevailing wind was from the north. He expressed the further opinion that if it held they should he off Dominica before tomorrow's dawn.

The Major, not to be left behind by Monsieur de Bernis in the display of knowledge of Caribbean matters, announced himself astonished that Captain Bransome should he putting in at an island mainly peopled by Caribs, with only an indifferent French settlement at Roseau. The readiness of the Frenchman's answer took him by surprise.

'For freights in the ordinary way I should agree with you, Major. Roseau would not be worth a visit; but for a Captain trading on his own account it can he very profitable. This, you may suppose to be the case of Captain Bransome.'

The accuracy of his surmise was revealed upon the morrow, when they lay at anchor before Roseau, on the western side of Dominica. Bransome, who traded in partnership with his owners, went ashore for a purchase of hides, for which he had left himself abundant room under hatches. He knew of some French traders here, from whom he could buy at half the price he would have to pay in Martinique or elsewhere; for the Caribs who slew and flayed the beasts were content with infinitely less than it cost to procure and maintain the Negro slaves who did the work in the more established settlements.

Since the loading of the hides was to delay them there for a day or two, Monsieur de Bernis proposed to his fellow passengers an excursion to the interior of the island, a proposal so warmly approved by Miss Priscilla that it was instantly adopted.

They procured ponies ashore, and the three of them, attended only by Pierre, de Bernis' half-caste servant, rode out to view that marvel of Dominica, the boiling lake, and the fertile plains watered by the Layou.

The Major would have insisted upon an escort. But Monsieur de Bernis, again displaying his knowledge of these regions, assured them that they would find the Caribs of Dominica a gentle, friendly race, from whom no evil was to be apprehended.

'If it were otherwise,' he concluded, 'the whole ship's company would not suffice to protect us, and I should never have proposed the jaunt.'

Priscilla rode that day between her two cavaliers; but it was the ready-witted de Bernis who chiefly held her attention, until Major Sands began to wonder whether the fellow's remarkable resemblance to his late Majesty might not extend beyond his personal appearance. Monsieur de Bernis made it plain, the Major thought, that he was endowed with the same gifts of spontaneous gallantry; and the Major was vexed to perceive signs that he possessed something of King Charles' attraction for the opposite sex.

His alarm might have gone considerably deeper but for the soothing knowledge that in a day or two this long-legged, gipsy-faced interloper would drop out of their lives at Sainte Croix. What Miss Priscilla could discern in the man, that she should bestow so much of her attention upon him, the Major could not imagine. As compared with his own solid worth, the fellow was no better than a shallow fribble. It was inconceivable that Priscilla should be dazzled by his pinchbeck glitter. And yet, women, even the best of them, were often, he knew, led into error by a lack of discernment. Therefore it was matter for thankfulness that this adventurer's contact with their own lives was destined to be so transient. If it were protracted, the rascal might become aware of the great fortune Miss Priscilla had inherited, and undoubtedly he would find in this an incentive to exert all the arts of attraction which such a fellow might command.

That he was an adventurer Major Sands was persuaded. He flattered himself that he could read a man at a glance, and his every instinct warned him against this saturnine rascal. His persuasions were confirmed that very evening at Roseau.

On the beach there, when they had relinquished their ponies, they came upon a burly, elderly, rudely clad Frenchman, who reeked of rum and tobacco, one of the traders from whom Captain Bransome was purchasing his hides. The man halted before them as if thunder-struck, and stared in round-eyed wonder al Monsieur de Bernis for a long moment. Then a queer grin spread upon his weather-beaten face, he pulled a ragged hat from a grizzled, ill-kempt head, with a courtesy rendered ironical by exaggeration.

Major Sands knew no French. But the impudently familiar tone of the greeting was not to be mistaken.

'C'est bien toi, de Bernis? Pardieu! Je ne croyais pas te revoir.'

De Bernis checked to answer him, and his reply reflected the other's easy, half-mocking tone. 'Et toi, mon drôle? Ah, tu fais le marchand de peaux maintenant?'

Major Sands moved on with Miss Priscilla, leaving de Bernis in talk with his oddly met acquaintance. The Major was curiously amused.

'A queer encounter for our fine gentleman. Most queer. Like the quality of his friends. More than ever I wonder who the devil he may be.

But Miss Priscilla was impatient of his wonder and his amusement. She found him petty. She knew the islands better, it seemed, than did he. She knew that colonial life could impose the oddest associations on a man, and that only the rash or the ignorant would draw conclusions from them.

She said something of the kind.

'Odds life, ma'am! D'ye defend him?'

'I've not perceived him to be attacked, unless you mean to attack him, Bart. After all, Monsieur de Bernis has never pretended that he comes to us from Versailles.'

'That will be because he doubts if it would carry conviction. Pish, child! The fellow's an adventurer.'

Her agreement shocked and dismayed him more than contradiction could have done.

'So I had supposed,' she smiled distractingly. 'I love adventurers and the adventurous.'

Only the fact that de Bernis came striding to overtake them saved her from a homily But her answer, which the Major accounted flippant, rankled with him; and it may have been due to this that after supper that night, when they were all assembled in the great cabin, he alluded to the matter of that meeting.

'That was a queer chance, Monsieur de Bernis, your coming face to face with an acquaintance here on Dominica.'

'A queer chance, indeed,' the Frenchman agreed readily. 'That was an old brother-in-arms.'

The Major's sandy brows went up. 'Ye've been a soldier, sir?'

There was an odd light in the Frenchman's eyes as for a long moment they considered his questioner. He seemed faintly amused.

'Oh, after a fashion,' he said at last. Then he swung to Bransome, who sat at his ease now, in cotton shirt and calico drawers, the European finery discarded. 'It was Lafarche, Captain. He tells me that he is trading with you.' And he went on: 'We were on Santa Catalina together under the Sieur Simon, and amongst the very few who survived the Spanish raid there of Perez de Guzman. Lafarche and I and two others, who had hidden ourselves in a maize field, when all was lost, got away that night in an open boat, and contrived to reach the Main. I was wounded, and my left arm had been broken by a piece of langrel during the bombardment. But all evils do not come to hurt us, as the Italians say. It saved my life. For it was my uselessness drove me into hiding, where the other three afterwards joined me. They were the first wounds I took. I was under twenty at the time. Only my youth and my vigour saved my arm and my life in the trials and hardships that followed. So far as I know we were the only four who escaped alive of the hundred and twenty men who were on Santa Catalina with Simon. When Perez took the island, he ruthlessly avenged the defence it had made by putting to the sword every man who had remained alive. A vile massacre. A wanton cruelty.'

He fell pensive, and might have left the matter there but that Miss Priscilla broke the ensuing silence to press him for more details.

In yielding, he told her of the colony which Mansvelt had established on Santa Catalina, of how they had gone to work to cultivate the land, planting maize and plantains, sweet potatoes, cassava, and tobacco. Whilst she listened to him with parted lips and softened eyes, he drew a picture of the flourishing condition which had been reached by the plantations when Don Juan Perez de Guzman came over from Panama, with four ships and an overwhelming force, to wreak his mischief. He told of Simon's proud answer when summoned to surrender: that he held the settlement for the English Crown, and that sooner than yield it up, he and those with him would yield up their lives. He stirred their blood by the picture he drew of the gallant stand made by that little garrison against the overwhelming Spanish odds. And he moved them to compassion by the tale of the massacre that followed and the wanton destruction of the plantations so laboriously hoed.

When he reached the end, there was a smile at once grim and wistful on his lean, gipsy-tinted face. The deep lines in it, lines far deeper than were warranted by his years, became more marked.

'The Spaniards paid for it at Porto Bello and at Panama and elsewhere. My God, how they paid! But not all the Spanish blood that has since been shed could avenge the brutal, cowardly destruction of the English and the French who were in alliance at Santa Catalina.'

He had impressed himself upon them by that glimpse into his past and into the history of West Indian settlements. Even the Major, however he might struggle against it, found himself caught in the spell of this queer fellow's personality.

Later, when supper was done, and the table had been cleared, Monsieur de Bernis went to fetch a guitar from among the effects in his cabin. Seated on the stern-locker, with his back to the great window that stood open to the purple tropical night, he sang some little songs of his native Provence and one or two queerly moving Spanish airs set in the minor key, of the kind that were freely composed in Malaga.

Rendered by his mellow baritone voice they had power to leave Miss Priscilla with stinging eyes and an ache at the heart; and even Major Sands was moved to admit that Monsieur de Bernis had a prodigious fine gift of song. But he took care to make the admission with patronage, as if to mark the gulf that lay between himself and his charge on the one hand and this stranger, met by chance, on the other. He accounted it a necessary precaution, because he could not be blind to the impression the fellow was making upon Miss Priscilla's inexperience. It was also, no doubt, because of this that on the morrow the Major permitted himself a sneer at Monsieur de Bernis' expense. It went near to making a breach between himself and the lady in his charge.

They were leaning at the time upon the carved rail of the quarterdeck to watch the loading, conducted under the jealous eyes of Captain Bransome, himself, who was not content to leave the matter to the quartermaster and the boatswain.

The coamings were off the main hatch, and by slings from the yardarm the bales of hides were being hoisted aboard from the rafts that brought them alongside. In the waist a dozen hairy seamen, naked above their belts, heaved and sweated in the merciless heat, whilst down in the stifling, reeking gloom of the hold others laboured at the stowage. The Captain, in cotton shirt and drawers, the blue kerchief swathing his cropped red head, his ruddy, freckled face agleam with sweat, moved hither and thither, directing the hoisting and stowing, and at times, from sheer exuberance of energy, lending a powerful hand at the ropes.

Into this sweltering bustle stepped Monsieur de Bernis from the gangway that led aft. As a concession to the heat he wore no coat. In the bulging white cambric shirt with its wealth of ruffles, clothing him above a pair of claret breeches, he looked cool and easy despite his heavy black periwig and broad black hat.

He greeted Bransome with familiar ease, and not only Bransome, but Sproat, the boatswain. From the bulwarks he stood surveying the rafts below with their silent crews of naked Caribs and noisily directing French overseers. He called down to them--Major Sands assumed it to be some French ribaldry--and set them laughing and answering him with raucously merry freedom. He said something to the hands about the hatchway, and had them presently all agrin. Then, when the trader Lafarche came climbing to the deck, mopping himself, and demanding rum, there was de Bernis supporting the demand, and thrusting Bransome before him to the after gangway, whilst himself he followed, bringing Lafarche with him, an arm flung carelessly about the villainous old trader's shoulder.

'A raffish fellow, without dignity or sense of discipline,' was the Major's disgusted comment.

Miss Priscilla looked at him sideways, and a little frown puckered her brow at the root of her daintily chiselled nose.

'That is not how I judge him.'

'No?' He was surprised. He uncrossed his plump legs, took his elbows from the poop-rail, and stood up, a heavy figure rendered the more ponderous by an air of self-sufficiency.

'Yet seeing him there, so very much at ease with that riff-raff, how else should he be read? I should be sorry to see myself in the like case. Stab me, I should.'

'You stand in no danger of it.'

'I thank-you. No.'

'Because a man needs to be very sure of himself before he can condescend so far.' It was a little cruel. But his sneering tone of superiority had annoyed her curiously.

Astonishment froze him. 'I...I do not think I understand. Stab me if I do.'

She was as merciless in her explanation, unintimidated by his frosty tone.

'I see Monsieur de Bernis a man placed by birth and experience above the petty need of standing upon his dignity.'

The Major collected the wits that had been scattered by angry amazement. After a gasping moment, he laughed. Derision he thought was the surest corrosive to apply to such heresies.

'Lord! Here's assumption! And birth, you say. Fan me, ye winds! What tokens of birth do you perceive in the tawdry fellow?'

'His name; his bearing; his...'

But the Major let her get no further. Again he laughed. 'His name? The "de," you mean. Faith, it's borne by many who have long since lost pretensions to gentility, and by many who never had a right to it. Do we even know that it is his name? As for his bearing, pray consider it. You saw him down there, making himself one with the hands, and the rest. Would a gentleman so comport himself?'

'We come back to the beginning,' said she coolly. 'I have given you reason why such as he may do it without loss. You do not answer me.'

He found her exasperating. But he did not tell her so. He curbed his rising heat. A lady so well endowed must be humoured by a prudent man who looks to make her his wife. And Major Sands was a very prudent man.