THE BOOK OF SAINTS AND FRIENDLY BEASTS - 20 Legends, Ballads and Stories E-Book

Abbie Farwell Brown

2,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Abela Publishing

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

THE BOOK OF SAINTS AND FRIENDLY BEASTS: stories of Saint Francis of Assisi and Other Saints Who Loved Animals It contains a collection of twenty legends, ballads and folktales for children and adults alike about saints - what they did and the animals they worked with from, mainly, the middle ages. So, if you’ve never heard of some of these saints, download a copy, pull up a chair and let yourself become engrossed in stories from days gone by.

The stories in this book are:

Saint Bridget and the King's Wolf

Saint Gerasimus and the Lion

Saint Keneth of the Gulls

Saint Launomar's Cow

Saint Werburgh and her Goose

The Ballad of Saint Athracta's Stags

Saint Kentigern and the Robin

Saint Blaise and his Beasts

Saint Cuthbert's Peace

The Ballad of Saint Felix

Saint Fronto's Camels

The Blind Singer, Saint Hervé

Saint Comgall and the Mice

The Wonders of Saint Berach

Saint Prisca, the Child Martyr

The Fish who helped Saint Gudwall

The Ballad of Saint Giles and the Deer

The Wolf-Mother of Saint Ailbe

Saint Rigobert's Dinner

Saint Francis of Assisi.

It also has “A Calendar of Saints' Days” which can be followed throughout the year.

===================

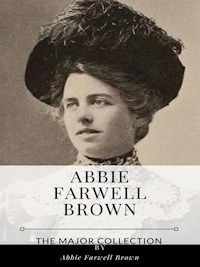

Abbie Farwell Brown (1871 to 1927) was an illustrator, author and sometimes editor. Her family resided in Beacon Hill, New England for ten generations, and Brown spent her entire life living in the family's home. She was the oldest of two children. Her sister, Clara, was also part of the literary world; she became an author and illustrator, using the pen name of Ann Underhill.

===================

KEYWORDS/TAGS: Book Of Saints, Friendly Beasts, 20 children’s stories, folklore, fairy tales, myths and legends, fables, Saints Who Loved Animals, middle ages, Saint Bridget, King's Wolf, Saint Gerasimus, Lion, Saint Keneth, Gulls, Saint Launomar, Cow, Saint Werburgh, Goose, Ballad, Saint Athracta, Stag, Saint Kentigern, Robin, Saint Blaise, Saint Cuthbert, Peace, Saint Felix, Saint Fronto, Camel, Blind Singer, Saint Herve, Saint Comgall, Mice, wonders, Saint Berach, Saint Prisca, Child Martyr, Fish, Saint Gudwall, Saint Giles, Deer, Wolf-Mother, Saint Ailbe, Saint Rigobert, Dinner, Saint Francis, Assisi,

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

The Book of Saintsand Friendly Beasts

By Abbie Farwell Brown

Illustrated By Fanny Y. Cory

Originally Published By

Houghton, Mifflin And Co. Boston And New York

[1900]

Resurrected ByAbela Publishing, London[2020]

The Book of Saints

and

Friendly Beasts

Typographical arrangement of this edition

© Abela Publishing

This book may not be reproduced in its current format in any manner in any media, or transmitted by any means whatsoever, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, or mechanical ( including photocopy, file or video recording, internet web sites, blogs,wikis, or any other information storage and retrieval system) except as permitted by law without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Abela Publishing,

London

United Kingdom

ISBN-: 979-1-X-XXXXXX-XX-X

email:

Website:

http://bit.ly/HekGn

ST. BRIDGET & THE KING'S WOLF

Dedication

IN LOVING MEMORY OF A FRIENDLY BEAST

Preface

Brother, Hast Thou Never Learned In Holy Writ, That With Him Who Has Led His Life After God's Will The Wild Beasts And Wild Birds Are Tame?

Saint Guthlac Of Crowland

IN the old legends there may be things which some folk nowadays find it hard to believe. But surely the theme of each is true. It is not hard to see how gentle bodies who had no other friends should make comrades of the little folk in fur and fins and feathers. For, as St. Francis knew so well, all the creatures are our little brothers, ready to meet halfway those who will but try to understand. And this is a truth which everyone to-day, even tho' he be no Saint, is waking up to learn. The happenings are set down quite as they read in the old books. Veritable histories, like those of St. Francis and St. Cuthbert, ask no addition of color to make them real. But sometimes, when a mere line of legend remained to hint of some dear Saint's relation with his friendly Beast, the story has been filled out in the way that seemed most likely to be true. For so alone could the old tale be made alive again. So all one's best is dressing old words new.

CONTENTS

Saint Bridget and the King's Wolf

Saint Gerasimus and the Lion

Saint Keneth of the Gulls

Saint Launomar's Cow

Saint Werburgh and her Goose

The Ballad of Saint Athracta's Stags

Saint Kentigern and the Robin

Saint Blaise and his Beasts

Saint Cuthbert's Peace

The Ballad of Saint Felix

Saint Fronto's Camels

The Blind Singer, Saint Hervé

Saint Comgall and the Mice

The Wonders of Saint Berach

Saint Prisca, the Child Martyr

The Fish who helped Saint Gudwall

The Ballad of Saint Giles and the Deer

The Wolf-Mother of Saint Ailbe

Saint Rigobert's Dinner

Saint Francis of Assisi

A Calendar of Saints' Days

The legend of Saint Fronto's Camels originally appeared in The Churchman.

Saint BRIDGET AND The King's Wolf

EVERY one has heard of Bridget, the little girl saint of Ireland. Her name is almost as well known as that of Saint Patrick, who drove all the snakes from the Island. Saint Bridget had long golden hair; and she was very beautiful. Many wonderful things happened to her that are written in famous books. But I suspect that you never heard what she did about the King's Wolf. It is a queer story.

This is how it happened. The King of Ireland had a tame wolf which some hunters had caught for him when it was a wee baby. And this wolf ran around as it pleased in the King's park near the palace, and had a very good time. But one morning he got over the high wall which surrounded the park, and strayed a long distance from home, which was a foolish thing to do. For in those days wild wolves were hated and feared by the people, whose cattle they often stole; and if a man could kill a wicked wolf he thought himself a very smart fellow indeed. Moreover, the King himself had offered a prize to any man who should bring him a dead wolf. For he wanted his kingdom to be a peaceful, happy one, where the children could play in the woods all day without fear of big eyes or big teeth.

Of course you can guess what happened to the King's wolf? A big, silly country fellow was going along with his bow and arrows, when he saw a great brown beast leap over a hedge and dash into the meadow beyond. It was only the King's wolf running away from home and feeling very frisky because it was the first time that he had done such a thing. But the country fellow did not know all that.

"Aha!" he said to himself. "I'll soon have you, my fine wolf; and the King will give me a gold piece that will buy me a hat and a new suit of clothes for the holidays." And without stopping to think about it or to look closely at the wolf, who had the King's mark upon his ear, the fellow shot his arrow straight as a string. The King's wolf gave one great leap into the air and then fell dead on the grass, poor fellow.

The countryman was much pleased. He dragged his prize straight up to the King's palace and thumped on the gate.

"Open!" he cried. "Open to the valiant hunter who has shot a wolf for the King. Open, that I may go in to receive the reward."

So, very respectfully, they bade him enter; and the Lord Chamberlain escorted him before the King himself, who sat on a great red-velvet throne in the Hall. In came the fellow, dragging after him by the tail the limp body of the King's wolf.

"What have we here?" growled the King, as the Lord Chamberlain made a low bow and pointed with his staff to the stranger. The King had a bad temper and did not like to receive callers in the morning. But the silly countryman was too vain of his great deed to notice the King's disagreeable frown.

"You have here a wolf, Sire," he said proudly. "I have shot for you a wolf, and I come to claim the promised reward."

But at this unlucky moment the King started up with an angry cry. He had noticed his mark on the wolf's right ear.

"Ho! Seize the villain!" he shouted to his soldiers. "He has slain my tame wolf; he has shot my pet! Away with him to prison; and to-morrow he dies."

It was useless for the poor man to scream and cry and try to explain that it was all a mistake. The King was furious. His wolf was killed, and the murderer must die.

In those days this was the way kings punished men who displeased them in any way. There were no delays; things happened very quickly. So they dragged the poor fellow off to a dark, damp dungeon and left him there howling and tearing his hair, wishing that wolves had never been saved from the flood by Noah and his Ark.

Now not far from this place little Saint Bridget lived. When she chose the beautiful spot for her home there were no houses near, only a great oak-tree, under which she built her little hut. It had but one room and the roof was covered with grass and straw. It seemed almost like a doll's playhouse, it was so small; and Bridget herself was like a big, golden-haired wax doll,—the prettiest doll you ever saw.

She was so beautiful and so good that people wanted to live near her, where they could see her sweet face often and hear her voice. When they found where she had built her cell, men came flocking from all the country round about with their wives and children and their household goods, their cows and pigs and chickens; and camping on the green grass under the great oak-tree they said, "We will live here, too, where Saint Bridget is."

So house after house was built, and a village grew up about her little cell; and for a name it had Kildare, which in Irish means "Cell of the Oak." Soon Kildare became so fashionable that even the King must have a palace and a park there. And it was in this park that the King's wolf had been killed.

Now Bridget knew the man who had shot the wolf, and when she heard into what terrible trouble he had fallen she was very sorry, for she was a kind-hearted little girl. She knew he was a silly fellow to shoot the tame wolf; but still it was all a mistake, and she thought he ought not to be punished so severely. She wished that she could do something to help him, to save him if possible. But this seemed difficult, for she knew what a bad temper the King had; and she also knew how proud he had been of that wolf, who was the only tame one in all the land.

Bridget called for her coachman with her chariot and pair of white horses, and started for the King's palace, wondering what she should do to satisfy the King and make him release the man who had meant to do no harm.

But lo and behold! as the horses galloped along over the Irish bogs of peat, Saint Bridget saw a great white shape racing towards her. At first she thought it was a dog. But no: no dog was as large as that. She soon saw that it was a wolf, with big eyes and with a red tongue lolling out of his mouth. At last he overtook the frightened horses, and with a flying leap came plump into the chariot where Bridget sat, and crouched at her feet, quietly as a dog would. He was no tame wolf, but a wild one, who had never before felt a human being's hand upon him. Yet he let Bridget pat and stroke him, and say nice things into his great ear. And he kept perfectly still by her side until the chariot rumbled up to the gate of the palace.

Then Bridget held out her hand and called to him; and the great white beast followed her quietly through the gate and up the stair and down the long hall, until they stood before the red-velvet throne, where the King sat looking stern and sulky.

They must have been a strange-looking pair, the little maiden in her green gown with her golden hair falling like a shower down to her knees; and the huge white wolf standing up almost as tall as she, his yellow eyes glaring fiercely about, and his red tongue panting. Bridget laid her hand gently on the beast's head which was close to her shoulder, and bowed to the King. The King only sat and stared, he was so surprised at the sight; but Bridget took that as a permission to speak.

"You have lost your tame wolf, O King," she said. "But I have brought you a better. There is no other tame wolf in all the land, now yours is dead. But look at this one! There is no white wolf to be found anywhere, and he is both tame and white. I have tamed him, my King. I, a little maiden, have tamed him so that he is gentle as you see. Look, I can pull his big ears and he will not snarl. Look, I can put my little hand into his great red mouth, and he will not bite. Sire, I give him to you. Spare me then the life of the poor, silly man who unwittingly killed your beast. Give his stupid life to me in exchange for this dear, amiable wolf," and she smiled pleadingly.

The King sat staring first at the great white beast, wonderfully pleased with the look of him, then at the beautiful maiden whose blue eyes looked so wistfully at him. And he was wonderfully pleased with the look of them, too. Then he bade her tell him the whole story, how she had come by the creature, and when, and where. Now when she had finished he first whistled in surprise, then he laughed. That was a good sign,—he was wonderfully pleased with Saint Bridget's story, also. It was so strange a thing for the King to laugh in the morning that the Chamberlain nearly fainted from surprise; and Bridget felt sure that she had won her prayer. Never had the King been seen in such a good humor. For he was a vain man, and it pleased him mightily to think of owning all for himself this huge beast, whose like was not in all the land, and whose story was so marvelous.

And when Bridget looked at him so beseechingly, he could not refuse those sweet blue eyes the request which they made, for fear of seeing them fill with tears.

So, as Bridget begged, he pardoned the countryman, and gave his life to Bridget, ordering his soldiers to set him free from prison. Then when she had thanked the King very sweetly, she bade the wolf lie down beside the red-velvet throne, and thenceforth be faithful and kind to his new master. And with one last pat upon his shaggy head, she left the wolf and hurried out to take away the silly countryman in her chariot, before the King should have time to change his mind.

The man was very happy and grateful. But she gave him a stern lecture on the way home, advising him not to be so hasty and so wasty next time.

"Sirrah Stupid," she said as she set him down by his cottage gate, "better not kill at all than take the lives of poor tame creatures. I have saved your life this once, but next time you will have to suffer. Remember, it is better that two wicked wolves escape than that one kind beast be killed. We cannot afford to lose our friendly beasts, Master Stupid. We can better afford to lose a blundering fellow like you." And she drove away to her cell under the oak, leaving the silly man to think over what she had said, and to feel much ashamed.

But the King's new wolf lived happily ever after in the palace park; and Bridget came often to see him, so that he had no time to grow homesick or lonesome.

Saint Gerasimus andThe Lion

I.

ONE fine morning Saint Gerasimus was walking briskly along the bank of the River Jordan. By his side plodded a little donkey bearing on his back an earthen jar; for they had been down to the river together to get water, and were taking it back to the monastery on the hill for the monks to drink at their noonday meal.

Gerasimus was singing merrily, touching the stupid little donkey now and then with a twig of olive leaves to keep him from going to sleep. This was in the far East, in the Holy Land, so the sky was very blue and the ground smelled hot. Birds were singing around them in the trees and overhead, all kinds of strange and beautiful birds. But suddenly Gerasimus heard a sound unlike any bird he had ever known; a sound which was not a bird's song at all, unless some newly invented kind had a bass voice which ended in a howl. The little donkey stopped suddenly, and bracing his fore legs and cocking forward his long, flappy ears, looked afraid and foolish. Gerasimus stopped too. But he was so wise a man that he could not look foolish. And he was too good a man to be afraid of anything. Still, he was a little surprised.

"Dear me," he said aloud, "how very strange that sounded. What do you suppose it was?" Now there was no one else anywhere near, so he must have been talking to himself. For he could never have expected that donkey to know anything about it. But the donkey thought he was being spoken to, so he wagged his head, and said, "He-haw!" which was a very silly answer indeed, and did not help Gerasimus at all.

He seized the donkey by the halter and waited to see what would happen. He peered up and down and around and about, but there was nothing to be seen except the shining river, the yellow sand, a clump of bushes beside the road, and the spire of the monastery peeping over the top of the hill beyond. He was about to start the donkey once more on his climb towards home, when that sound came again; and this time he noticed that it was a sad sound, a sort of whining growl ending in a sob. It sounded nearer than before, and seemed to come from the clump of bushes. Gerasimus and the donkey turned their heads quickly in that direction, and the donkey trembled all over, he was so frightened. But his master only said, "It must be a Lion!"

And sure enough: he had hardly spoken the word when out of the bushes came poking the great head and yellow eyes of a lion. He was looking straight at Gerasimus. Then, giving that cry again, he bounded out and strode towards the good man, who was holding the donkey tight to keep him from running away. He was the biggest kind of a lion, much bigger than the donkey, and his mane was long and thick, and his tail had a yellow brush on the end as large as a window mop. But as he came Gerasimus noticed that he limped as if he were lame. At once the Saint was filled with pity, for he could not bear to see any creature suffer. And without any thought of fear, he went forward to meet the lion. Instead of pouncing upon him fiercely, or snarling, or making ready to eat him up, the lion crouched whining at his feet.

"Poor fellow," said Gerasimus, "what hurts you and makes you lame, brother Lion?"

The lion shook his yellow mane and roared. But his eyes were not fierce; they were only full of pain as they looked up into those of Gerasimus asking for help. And then he held up his right fore paw and shook it to show that this was where the trouble lay. Gerasimus looked at him kindly.

"Lie down, sir," he said just as one would speak to a big yellow dog. And obediently the lion charged. Then the good man bent over him, and taking the great paw in his hand examined it carefully. In the soft cushion of the paw a long pointed thorn was piercing so deeply that he could hardly find the end. No wonder the poor lion had roared with pain! Gerasimus pulled out the thorn as gently as he could, and though it must have hurt the lion badly he did not make a sound, but lay still as he had been told. And when the thorn was taken out the lion licked Gerasimus' hand, and looked up in his face as if he would say, "Thank you, kind man. I shall not forget."

Now when the Saint had finished this good deed he went back to his donkey and started on towards the monastery. But hearing the soft pad of steps behind him he turned and saw that the great yellow lion was following close at his heels. At first he was somewhat embarrassed, for he did not know how the other monks would receive this big stranger. But it did not seem polite or kind to drive him away, especially as he was still somewhat lame. So Gerasimus took up his switch of olive leaves and drove the donkey on without a word, thinking that perhaps the lion would grow tired and drop behind. But when he glanced over his shoulder he still saw the yellow head close at his elbow; and sometimes he felt the hot, rough tongue licking his hand that hung at his side.

So they climbed the hill to the monastery. Someone had seen Gerasimus coming with this strange attendant at his heels, and the windows and doors were crowded with monks, their mouths and eyes wide open with astonishment, peering over one another's shoulders. From every corner of the monastery they had run to see the sight; but they were all on tiptoe to run back again twice as quickly if the lion should roar or lash his tail. Now although Gerasimus knew that the house was full of staring eyes expecting every minute to see him eaten up, he did not hurry or worry at all. Leisurely he unloaded the water-jar and put the donkey in his stable, the lion following him everywhere he went. When all was finished he turned to bid the beast good-by. But instead of taking the hint and departing as he was expected to, the lion crouched at Gerasimus' feet and licked his sandals; and then he looked up in the Saint's face and pawed at his coarse gown pleadingly, as if he said, "Good man, I love you because you took the thorn out of my foot. Let me stay with you always to be your watch-dog." And Gerasimus understood.