Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

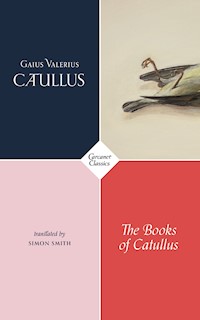

- Herausgeber: Carcanet Classics

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

The Books of Catullus is the first full English translation to take the Roman poet at his word. Simon Smith's versions are scholarly yet eccentric, mapping theme and register to contemporary equivalents (such as poem 16, which echoes Frank O'Hara). He divides Catullus's complete verses into three 'books', the form in which it is thought the poems were originally received. 'Smith gets the all-important rhythm of Catullus, whose meters, like all else about this poet, are deceptively complex', writes Vincent Katz. 'He achieves a delicious frisson again and again by fusing the classical and the contemporary. The reader is repeatedly pleasured by unexpected felicities.' (Peter Hughes)

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 123

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

the books of CATULLUS

translated and edited by

Simon Smith

Contents

to the teachers, particularly Reg Nash for the Latin and Olive Burnside for the poetry

Introduction

Catullus is one of the most popular and most translated Latin poets. His popularity continues to grow, with the variety of translations proliferating and accelerating since the 1960s. The dates of his birth and death are uncertain; according to St Jerome, Gaius Valerius Catullus was born in Verona in 87 BCE and died in Rome in 57 BCE. However, evidence from the poems shows that he was still alive as late as 54 BCE: Poem 11 alludes to Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britain. Mention of the soldier and politician in a scattering of poems make it clear Catullus was living at the time of Caesar (apparently a friend of his father’s) and other Roman notables, who walk into (and then out of) the poems, such as Cicero. He was on the staff of Memmius in the province of Bithynia in 57 (Poem 10), and knew contemporary Roman poets and writers such as Cornelius Nepos, the dedicatee of the poems (Poem 1). The identification of his lover, the noblewoman Clodia Metelli, named ‘Lesbia’ in the poems, is not a certainty, although likely. In addition, the text shows the poet was familiar with, and translated versions of, the Greek and Hellenic poets Sappho and Callimachus. These facts, and others gleaned from the poems and corroborated by secondary sources, are as much as we can be certain of.

Despite the scarcity of facts about Catullus’s life, there is enough circumstantial evidence, wider historical record and textual allusion to build a biographical interpretation of the poems. Indeed, Daisy Dunn’s Catullus’ Bedspread: The Life of Rome’s Most Erotic Poet is full-blown biography, proving that this approach to Catullus and his poems, which perpetuates his reputation as Latin literature’s most popular and accessible poet, can yield a fast-paced read. Fictional accounts of Catullus’s life and times are not unheard of either, nor are they particularly new: Thornton Wilder’s epistolary novel The Ides of March, dating from 1948, is a minor masterpiece in its own right.

The biographical approach to Catullus is so attractive because of, rather than despite, the limited factual evidence. What facts we do have (very few), combined with scraps of suggestive hearsay (rather more), amount to a partial account with enough scope for creative interpolation that a convincing and absorbing story is easily constructed. Such accounts recover Catullus from anonymity and obscurity (the resting place of most Latin poets) and make of him an apparently red-blooded, three-dimensional protagonist.

This attraction to biography does not rise plainly and simply from the salacious content of the poems, but equally from their seeming intimacy, the way they address the reader personally. For example, Poem 8 – the first poem this translator attempted – positions the reader as if looking through a keyhole onto a familiar, intimate, and immediate world whose relationships carry the same emotional and psychological turmoil as modern ones, while simultaneously occupying a strange world which, the longer the reader inspects and inhabits it, becomes quite other. The reader is lured into identifying with the protagonist and his lover; however, once he understands the importance of social class for Catullus and Lesbia, their very different ages (he was in his twenties, she in her mid-to-late thirties) and the significance of these two factors in historical context, the poem begins to look quite different.

First: because of the relatively low life expectancy in Late Republican Rome, the age gap would be a generational one. Second: in Roman culture of the Late Republic, a marriage might be impossible because of differences in class; in this case, Clodia Metelli was of a higher class than Catullus, an affluent young man from the provinces. An affair, however, would be tolerated. Today, these are private matters, for the judgment of individuals. For the modern-day reader approaching the poem anew, unfamiliar with its cultural nuances, there is a risk: encouraged by the poem’s seeming familiarity and the apparent simplicity of the lovers’ situation, he is lured into an act of cultural appropriation, eliding the poem’s historical reality. The seduction of biographical reading has led to the popular notion that Catullus is ‘accessible’, or more accessible than other Latin poets of that period, that he is more ‘like us’, preternaturally modern. In reality the situation is more complex and problematic than it first seems.

The order in which we should read these poems is just as uncertain as the biography of the poet. Indeed, the information available follows a similar pattern: there is just enough evidence to support an authorial ordering and not quite enough to mark that evidence with a stamp of certainty. Who arranged the poems? The poet, or some later, unknown editor or editors? This translation holds to the ‘three-book’ structure favoured by many scholars of recent years, from T. P. Wiseman to Marilyn Skinner, a structure rejected by other scholars and translators including A. L. Wheeler and D. F. S. Thomson.

The ‘three-book’ structure tends towards authorial ordering, with some possible later editorial intervention. The translations in this volume follow the guidance of the commentaries, particularly that of Thomson in 1998, the most recent commentary on the source text. My versioning of Catullus breaks the three books into three accepted groupings: polymetrics (Poems 1–60), the long poems on marriage (61–64), and the elegies and epigrams (65–116). Most translations present all 116 as one continuous text, but there have been various attempts to re-order them. The more extreme orderings either attempt a kind of thematised poetic biography (Jacob Rabinowitz) or corral the poems strictly by theme (Josephine Balmer). One thing revealed by these re-orderings is how lines, phrases and whole passages are occasionally repeated. When they appear side-by-side the poems start to become repetitious and boring, and somehow lose their energy. Indeed, what becomes clear is that the poems need to be dispersed through a sequence, so that Catullus’s reflections on love, politics, friendship and so on develop across and through the body of work, across all three ‘books’, revealing (to some extent) authorial intent in the arrangement of the poems as they are.

Other evidence for authorial ordering is tantalising. Perhaps most compelling is the account of critic and translator Charles Martin, who characterises the patterning of the poems and how they ‘speak’ to one another across the span of the texts as chiastic: for example, Poem 61 (on marriage) ‘speaks’ to Poem 68 (on adultery). The poems also use chiasmus internally, for example Poem 57, which is topped and tailed by the same line. Martin demonstrates the chiastic patterning in Poem 64, where the eight scenes of the poem create a form of chiastic framing:

I. The courtship of Peleus and Thetis (lines 1–31)

II. The wedding feast, Part I (lines 32–50)

III. Ariadne’s search (lines 51–116)

IV. Ariadne’s lament (lines 117–202)

Bridge: The Judgment of Jove (lines 203–207)

V. Aegeus’ lament (lines 208–250)

VI. Iacchus’ search (lines 251–265)

VII. The wedding feast, Part II (lines 266–382)

VIII. Conclusion (lines 383–410)

The crucial moment comes at the ‘bridge’, when Jove delivers his judgment on Theseus’s neglect of Ariadne and his failure to replace his ship’s black sail with a white one, as his father asked (a signal of Theseus’s triumphant return after slaughtering the Minotaur). The poem hinges on line 205, the central line to the poem and a pivot within the three ‘books’: ‘the Heavenly Power nodded unstoppable / approval’ – a line that seems straightforwardly positive, a god granting a wish to Ariadne, but which leads to the immediate suicide of Aegeus, and a darkening of the second half of the poem and of ‘book three’. These kinds of decisions on the ordering of the poems seem more like those of an author than a later editor. They are also choices consistent with the poems’ internal logic and aesthetic, and therefore more likely authorial than editorial. In short, alternative arrangements of the poems are simply not as convincing, or as successful, as the ordering of the three books, as they have been handed down.

In the present volume, the differences in metrics between these ‘books’ are shadowed by differences in syllable count, to produce a line-by-line translation. My version of the first book, in which Catullus uses a variety of metres, is the freest in its treatment of the poems’ literal meanings, physical shapes and layout. These liberties allowed me to embrace the wider importance of Catullus in modern culture; for instance, my versions of Poems 16, 25, and 48 echo lines of Frank O’Hara, whose poems change the reader’s view of New York City ‘like having Catullus change your view of the Forum in Rome’ (Allen Ginsberg). So these translations try for cultural equivalence as well as textual accuracy. They show that Catullus’s poems are in dialogue with current and recent poetries, and suggest Catullus’s important influence on the development of anglophone poetries down the centuries since the Renaissance, when Catullus was first Englished.

In the second and third books this shadowing is much stricter. Here my versions hug closer to the originals line-by-line, reflecting a new astringency in the rhythm and metre as a darker, bitterer tone develops. ‘In poetry’, wrote Robert Lowell in his introduction to Imitations, speaking of what, in essence, translation must achieve, ‘tone is of course everything’. If this translation aspires to achieve one thing, it is to register the shifts of tone in the original. It became clear, in the process of working away at the translations in this volume, that a unique quality of Catullus’s ‘books’ is this shifting tone, in tonal weight, away from the lightness of the polymetrics, through the more mature ‘wedding’ poems (is there a sense here of the poet taking life more seriously?), to the darker tone of ‘book three’, darkened by the death of the poet’s brother, whose absence looms over the final book; by the poet’s resignation to the withering of his relationship with Lesbia; and later by the barbed, sometimes desperate, often violent epigrams.

Hand-in-hand with the work’s metrical groupings and tonal modulations are its shifts in diction (which similarly tack and veer within a poem or a single line), its soundings of voice (in the form of nuanced raising and lowering), and its complications of syntax. These shifts, soundings and complications give the ‘books’ characteristic dimensions and unique signatures that a simple division of the poems by their metrics would not. This is why shadowing the later texts closely, line-by-line, was crucial. It allowed me to preserve the meaning of the poem at a microtextual level, to retain the complexity and sophistication of the originals. A good example is Poem 97, which has been somewhat overlooked by critics because of its extreme obscenity, but which shows why line-by-line translation is important when it comes to understanding Catullus’s poetry and the unique movement of his line. Poem 97 is a rhetorical tour de force, using the elegiac couplet as its vehicle, which gains momentum as it unfolds line-by-line, one image opening onto the next, from the outrageous to the grotesque, before coming to rest in almost surrealist fantasy. The obscenity of the poem acts as a screen, as a form of bathos or exercise of the non-poetic, to mask the poem’s aesthetic sophistication.

My focus on the differences between the three ‘books’, between the various genres within them, and on the poems’ intricate shifts in tone, voice and mood, have not been as much a focus of earlier translations. Previous translations have tended to homogenise the poems, flattening their voice and tone. But translators that elide these subtleties, these difficulties, reduce the essential texture of the work. This translation attempts to shadow the original with the purpose of highlighting and revealing these features of the source text as fully as possible. Approaches as different as Josephine Balmer’s thematic ordering, Peter Whigham’s William Carlos Williams versioning, the Zukofskys’ homophonic soundings, all tend towards their own totalising homogeneity.

The purpose of this volume is to add to the conversation between different translations of Catullus. What is clear is that Catullus’s ‘books’ have come to occupy a unique place in the canon of Englished poetry. The text of the 116 poems is translated in its entirety from the late nineteenth century onwards (and increasingly by poets). Two fundamental ambiguities – Catullus’s biography, and the ordering of the poems – turn each new attempt to translate Catullus over the centuries into a reflection of the cultural, literary, moral and emotional needs of the translator and, to an extent, his or her times. A translation of Catullus is as much a new perspective on Catullus as on ourselves, our life and culture. There is a vacuum left by a lack of facts about the poems and the poet, and a generation of conjecture rushes energetically to fill it. Each conjecture is inevitably a product of the translator’s own foibles, predispositions and epoch.

Via Petrarch, and the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English translations of the ‘kiss’ and ‘sparrow’ poems, Catullus has had a huge influence on the shaping of English love poetry. And therein lies the challenge. Because Catullus’s poetry forms a significant strand of our shared poetic dna, a poet working in English must first translate Catullus in order to understand his or her own work and the work of their generation.

WORKS CITED

Josephine Balmer (translator), Catullus: Poems of Love and Hate (Tarset: Bloodaxe Books, 2004)

Daisy Dunn,