Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Al-Mashreq eBookstore

- Kategorie: Erotik

- Sprache: Englisch

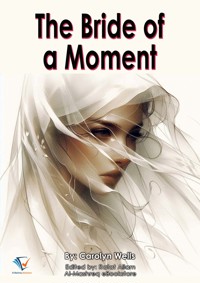

The Bride of a Moment by Carolyn Wells is a captivating tale of love, mystery, and unexpected twists. When a charming but mysterious stranger proposes to a beautiful young woman, the world is taken aback by their whirlwind engagement. But what seems like a fairy-tale romance quickly turns sinister as secrets from the stranger's past threaten to unravel the couple's happiness. As the bride delves into the enigmatic life of her fiancé, she uncovers a web of deceit and danger that could cost her everything. Will she discover the truth before it's too late, or will her momentary dream turn into a nightmare? Dive into this thrilling romance and unravel the secrets hidden beneath the surface.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 330

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

The Bride of a Moment

I - A June Wedding

II - The Silent Shot

III - A Few Bars of Music

IV - The Pearl Veil Pin

V - The East Side of the West?

VI - A Woman’s Will

VII - Warry’s Getaway

VIII - The Family Lawyer

IX - The Turning Point

X - The Woman at the Window

XI - The Woman the Bridegroom Loved

XII - Two Telegrams

XIII - Alan Ford

XIV - A Musical Cipher

XV - Flora Wood

XVI - Hal Kennedy

XVII - The Cipher Solved

XVIII - A Downward Course

XIX - Caprice

XX - The Music of the Choir

XXI - The Call of the Siren

XXII - Ford’s Theory

XXIII - Only One Way

XXIV - A Midnight Marriage

Landmarks

Table of Contents

Cover

The Bride of a Moment

I - A June Wedding

A big limousine came to a standstill beneath the porte-cochère of the church, and with much watchful protection of their frocks from possible damage, two girls got out of the car and hurried into the church.

Their elaborate gowns, exactly alike, their twin flower-decked hats, and their enormous bouquets proclaimed them bridesmaids. Smilingly they separated themselves from the crowd pouring in at the church doors, and then stood waiting in that end of the vestibule reserved for the purpose.

“I’m glad we’re here first,” exclaimed Betty Stratton, in a stage whisper; “and oh, goody! somebody has put a long mirror here. Aren’t our frocks wonderful? I’m just crazy over them!” She smiled and preened before the glass in a very ecstasy of delightful excitement “It’ll be the greatest wedding ever. Ethel is the most beautiful girl I know.”

“Yes, in her way,” agreed the other bridesmaid, as she elbowed Betty away from the mirror, and carefully touched her pink cheek with a powder-puff; “she’s stunning—like a statuesque goddess—”

“No, she’s more like those wax angels we used to have at the top of a Christmas tree. How do you like him?” and Betty gazed in absorbed admiration at her own fascinating reflection.

“Mr. Bingham? I don’t know him very well, but I think he’s just the man for a bridegroom. He’s so perfectly polished—if you know what I mean.”

“Yes, isn’t he! They’ll look wonderful coming down the other aisle, afterward. The presents are beyond words! My dear! she has forty-eight silver candlesticks! Forty-eight! And the silver bowls and dishes! M—m—!”

What did he give her?”

“A solitaire diamond pendant The biggest one I ever saw, and more than flawless! No setting, you know, just a thread of a silver chain. Oh, Molly, do you s’pose I’ll ever get married to a rich man—”

“Hush; here comes the bride, and the other girls—oh, Ethel!”

With the aid of several assistants and advisers, the bride and her regalia were safely piloted from the motor-car to the church, and in the vestibule the lovely vision was disclosed to the adoring eyes of her satellites.

The bridal gown was the last word of fashion, and the cap, for a wonder becoming, crowned the soft golden hair and exquisite face of the most haughty beauty of Boscombe Fells. But the face was as white as the encircling lace. The pale lips trembled and the violet eyes now stared with a frightened look, and now were hidden by the white, golden-fringed lids that drooped over them.

For once the cool, calm poise of Ethel Moulton was shaken. For once the proud, imperious beauty looked humble and even afraid. She stood passively while attendants adjusted her train and veil. She watched with unseeing eyes as the rest of the bridal party gathered and formed in line. She glanced in the mirror, and, seeing the white, scared face, she smiled and flushed scarlet, only to turn ashy pale again the next moment.

“Now, Ethel,” said Betty Stratton for the twentieth time, “you must control yourself! Smile and look happy or I’ll shake you! Look as pensive as you like, but don’t spoil this whole show by acting as if you were a lamb dragged to the altar—or whatever it is. Get your mind off of it, if it affects you that way. Think of the last vaudeville show you saw—think of chicken hash with green peppers,—think of anything pleasant and gay!”

“Stop it, Betty,” said Eileen Randall, the maid of honour, “let her alone! She shan’t be ‘bused! It’s quite all right for a bride to look nervous,—it’s much more interesting. Isn’t it time to start?”

The whole bridal cortege was now crowded into the vestibule of the church, nervously awaiting the stroke of twelve. The bridesmaids stood demurely, if restlessly, in their appointed places, but the maid of honour still darted about here and there, adjusting, supervising, reminding.

“Cheer up, Mr. Swift,” she said to the soldierly-looking grey-haired man who stood beside the bride; “you’ll never have to give Ethel away again, so do it prettily this time, Keep your eyes straight ahead, don’t look either up or down, and everybody will say, ‘How beautifully he behaves!’ Ethel, dear, now do brace up! Bridal shyness is all very well,—but you mustn’t look like a wilted lily. What time is it, Mr. Farrish? Oh, you men do look sweet in your clean white kimonos.”

Guy Farrish, one of the vested choir who were waiting to lead the bridal procession down the aisle, answered: “Only four minutes more, Miss Randall! Better get your place.”

The bride looked up, startled. Only four minutes more! “I can’t—” she said; “I can’t go—oh, I can’t go!”

“There, there, Ethel,” said her uncle, “don’t talk like that, my girl. Brace up; come, now, is your bouquet all right? It’s about time to start.”

“Yes, it’s all right,” said the maid of honour, giving the mass of white orchids and valley lilies a final pat and then, after a swift glance in the long mirror at her own pink-streamered bunch of roses, she slipped into her place, and said, “Ready, girls! Watch your step!”

Eileen Randall was a born commander. As maid of honour at her friend’s wedding, she had organized and directed all the elaborate details of the affair. It was she who had insisted on the full choral service, who had designed the wonderful floral decorations, and who had even chosen the costumes, the bridesmaids’ frocks of pale pink taffeta brocaded with blue and silver roses, her own pink tulle over blue, and even the bridal gown of white and silver brocade. She had planned the procession and conducted its rehearsal, and now at the last moment she glanced around, well satisfied with her results.

The first two choristers stood in the doorway that led into the church, their eyes on the organ at the farther end. The ushers came, importantly, and took their places. Through a tiny opening of the door beside the pulpit, the best man watched, and reported progress in whispers to the determinedly composed bridegroom.

The church, a complacent, comfortable affair, of Congregational denomination, was usually of a dim unresponsiveness, but to-day it seemed to shine and sing in epithalamium. The June sunshine crowded in at the open windows, and the stained-glass panes above threw riotous colour-effects on the already gaily clad audience.

For Boscombe Fells was as pretentious as its name indicates. A small settlement of exclusive people, not far from New York City, it prided itself on being a worth-while place to live, and in such matters as wedding pageants and the like its taste was correct and exacting.

The first note of noon pealed from the church clock. The organ sounded, the eight members of the vested choir started singing, down the aisle toward the flower-banked pulpit. Followed the ushers, the dainty bridesmaids, the maid of honour, and then the bride, beautiful Ethel Moulton, on the arm of her uncle, Everson Swift. White as her own orange-blossoms, the girl trembled until her uncle, alarmed, so far forgot the instructions of the maid of honour as to steal a side glance at his charge. An instant’s flash of her blue eyes reassured him, and he thought no more of the bride’s most natural agitation. Her trembling ceased and she was calm save for the quick rise and fall of the great diamond, the gift of the bridegroom, which hung on her breast, held only by an invisible silver chain.

On they went to the music of the processional; slowly, and still singing, the choir ascended into the organ loft, behind the pulpit, the bridesmaids took their places indicated by faint chalk marks on the carpet, and the maid of honour, seeing that the bridegroom and best man were conducting themselves correctly, took her own place at the left of the bride.

The music grew fainter. The whispered harmonies of “The Voice That Breathed O’er Eden” did not drown the sonorous tones of the minister, who asked the vital questions of the pair kneeling before him.

Mr. Swift gave his niece away, with a heart full of gladness. He loved the girl, his dead sister’s child, and he knew he was giving her to a man of fine, sterling character. Stanford Bingham, a man of nearly thirty, was well-born, rich, and talented. What more could he ask for Ethel? And Mrs. Swift, in her place in the front pew, looked on complacently, as she awaited her husband’s return to her side. His part done, Everson Swift turned, smiling, and went to his seat in the front pew, and Ethel was left, her hand in that of the man who in another moment would be her husband.

Parrot-like, the vows were repeated after the minister. The ring was placed carefully on the white finger in its ripped glove, and Doctor Van Sutton pronounced Stanford Bingham and Ethel Moulton man and wife.

The benediction was spoken, and then, as the minister smilingly took the bride’s hand, the organ pealed, the choir sounded forth glorious notes, and the hush that had been upon the assemblage gave way to a sudden hubbub of gay laughter and chatter.

And then, without a word, without a sound, the bride dropped to the floor.

The maid of honour who was adjusting the white and silver brocaded train, preparatory to the march down the other aisle, gazed, stunned, at a crimson stain that spread slowly over the bridal veil and bodice. She saw the beautiful terrified face, and the wide, frightened eyes, and then the lovely head fell, and veil, silver brocade, and white orchids were crushed in a terrible crumpled heap.

What had happened? The bridegroom stood as if turned to stone. The bridesmaids screamed. The maid of honour clenched her hands and gritted her teeth in a determination not to faint, and Mrs. Everson Swift turned uncomprehending eyes to her husband, saying, “What is the matter, dear?”

It was the best man who made the first move. Warren Swift, Ethel’s cousin, tried to raise the fallen figure.

“My God! She’s shot!” he exclaimed, without thought of decorum or caution. He lifted his head, wild-eyed, and looked around.

Others crowded up then. The ushers, the people from the front pews, the bridesmaids, all glanced at the bride, and then turned, white-faced, to gaze at each other. The choristers and organist came down from their places and stood aside, aghast.

Everson Swift went to his niece, as the others fell back to let him pass. “Has she fainted?” he said, tremblingly, not willing to believe or imply what he feared.

“She is shot, father,” said his son, Warren; “shot.”

“But I heard no sound, no shot—” and the older man looked dazed and helpless.

“Lift her up,” said Eileen Randall, imperatively; “don’t leave her there on the floor! She isn’t dead.”

Hesitatingly, Warren Swift leaned toward the ghastly heap of bridal finery, and then drew back, unable to obey the dictatorial maid of honour.

Two of the ushers stepped forward. “We will take her,” said one of them; “where to, Miss Randall?”

“Into the church parlour,—I’ll show you the way.”

Eileen crossed to the right of the pulpit and opened a door, the one through which the bridegroom and his best man had come so short a time before. It opened into a quaint old-fashioned room, known as the church parlour, which was used for meetings of the Sewing Society and other church organizations. The two men followed, gently bearing their pathetic burden.

“Lay her here,” directed Eileen, as she smoothed a pillow on a wide old-fashioned sofa.

And there they laid the beautiful, still form of the white-robed bride.

Unable to keep away, others came. The uncle and aunt, the cousin, and then the bridegroom,—looking like a man in a dream. He stood staring at his bride, at the masses of white satin and lace and tulle that seemed to billow over the old sofa and lie in foamy waves on the floor, at the terrible, hideous wound that changed the beautiful face to a horror.

Doctor Endicott, the family physician of the Swifts, came hurrying in. Pushing the others away, he examined the wound in the right temple; he felt the pulse; he listened for heart-beats. Eagerly he strove to find some sign of life,—some ground for hope. But at last, with a sigh of despair, he shook his head.

“Death was instantaneous,” he said, straightforwardly. “Who fired that bullet?”

Not only did no one answer, but almost none present grasped the significance of his words. A bride, shot and killed at the altar! It was too unbelievable! Such a thing could not happen. Mrs. Swift clung to her husband in dumb terror. The bridesmaids huddled together in shuddering fear. Even the capable and brave Eileen succumbed and dropping into a chair hid her face and sobbed. The men stood baffled and helpless. Warren Swift looked dazed and terror-stricken, as he edged over toward his father and mother in an impulse of family feeling.

The bridegroom stood alone. At the head of the couch where lay his new-made bride, Stanford Bingham stood, with folded arms and set face, looking down at the awful sight.

Into the hushed room came the minister.

“I must dismiss the congregation,” he said, addressing himself to Mrs. Swift

“Yes,” replied her husband, for she could not speak, nor, indeed, understand what was said.

Then Everson Swift pulled himself together. Many things must be attended to, and he, of course, must take the helm.

“Yes, Doctor Van Sutton,” he went on; “ask the people to go away, and then we must—we must notify the—the police, I suppose.”

“Yes, it is necessary. Perhaps Mrs. Swift will go home now?”

“It would be better. Go, my dear; Warren, go with your mother.”

Submissively, Warren Swift took his mother by the arm and led her away. Her gorgeous gown of pearl-embroidered mauve satin trailed far behind her, and accented the awfulness of the occasion. “Oh,” she cried suddenly, “I can’t go home,—to that house!”

And all suddenly had a mental vision of the spacious home, decorated in gala mood, for the home-coming of the bride; the floral bower in the drawing-room, the laden tables in the dining-room, the going-away gown and hat in Ethel’s own room—how could she go back there?

“Don’t go there now, Mrs. Swift,” said Eileen Randall, raising her head; “oh, don’t! Go to my home; Charlotte is there, she’ll look after you. Take your mother there, Warry.”

And still Stanford Bingham stood, immovable, looking down on his murdered bride.

The minister returned to the church. The tumultuous throng of wedding guests hushed their excited talk to listen to him. He told them the bride had died suddenly, he did not say by what means. He asked them to go home, and he pronounced a broken-voiced benediction. In many strange positions the Reverend Doctor Van Sutton had found himself, but never before in one so terrible as this.

The congregation moved out slowly. The better-minded ones went at once, but others, curious and questioning, could not tear themselves from the scene of mystery and tragedy.

Twice, at intervals, the minister repeated his request that the church be vacated. The second time he was obliged to make it an order, and even then, it was not until the blue-coated officers of the law appeared that the last intrusive lingerers were induced to go.

Seeing a great heap of white flowers in front of him, half unconsciously the minister picked up the bride’s bouquet. Helplessly he gathered up its trailing, ribbon-tied sprays, and returning to the church parlour, he laid it, with a vague idea of the fitness of things, on the breast of the still white form on the sofa.

It was too dreadful. That touch completed the horrible mockery of the wedding array, and with an hysterical scream Betty Stratton ran out of the room and went home. The other three bridesmaids followed her, but Eileen Randall stayed, shaken to her very soul, but ready to do her part, whatever it might be.

II - The Silent Shot

Inspector Kinney entered the church parlour with an expression of profound bewilderment on his big, homely face. Accustomed as he was to all manner of dreadful and horrible crimes, the murder of a bride at the altar was startling even to him. Baring his head, he advanced reverently to the beautiful still figure on the sofa.

“Who done it?” he said, clenching his fists and glancing from one to another of the silent people gathered about.

“We have no idea,” said Mr. Swift, who was naturally spokesman; “she was, of course, shot, but no one seems to have heard the report of a pistol.”

“One of them newfangled kind; they don’t make no noise, hardly,” and Kinney nodded his head, sagaciously. “Better get the detectives on the case, right off. And there’s too many people in here. Everybody must clear out, exceptin’ the nearest kin.”

“I must stay,” said Eileen Randall, assertively, “I’m the maid of honour, and I want to stay near Ethel, whatever happens.”

“All right, miss, you can stay.”

Kinney was also willing that the bridegroom should stay, and the uncle of the dead girl, but others he put out.

“You three choir men, now,” he went on, glancing at the group in cassocks and cottas, “you ain’t got no call here, ‘ceptin’ curiosity, and you’d better go.”

The three, who were all friends of the dead bride, started, on being thus spoken to, and rather reluctantly moved away. Guy Farrish cast a last glance at the fair white face, and left the room. Hal Kennedy paused a moment for a longer look, and then followed. But Eugene Hall, the third of the singers, asked permission to stay until the coroner came.

“Oh, well, stay if you want to,” said the Inspector, “you can, of course, only I don’t want a lot of unnecessary folks around.”

“You’re right, Kinney,” said a voice, and a young man came in from the church. “There’s a crowd outside getting bigger every minute. Don’t let any more in here.”

The newcomer was Bob Keene, a reporter, who had expected to write up a graphic account of the wedding, and who now found it his dreadful duty to report the tragedy.

“I tried to keep out of this,” he said to Eileen, whom he knew, “but my boss insisted I should come. Who could have done it? Have you any idea?”

“No,” returned the girl, in low tones like his own. “I can’t see any light on the mystery or any way to look for light. The whole thing is so—so unbelievable! I can’t realize yet that Ethel is—is gone!”

“Old Bingham can’t either! Look at him! He seems absolutely dazed.”

“Of course he is! Think of the shock. Poor man—”

“It’s fierce! I was in the church, and I didn’t hear anything that sounded like a shot.”

“Neither did I. Mr. Kinney says there are pistols that don’t make any noise,—it must have been one of those.”

“I’ve heard of them, but I didn’t know they were really soundless. However, I suppose the music drowned what sound there was. Hello, here’s the Coroner. Hartt’s a good fellow, he’ll find out something, I’ve no doubt.”

Coroner Hartt came in, followed by a detective of the Police Bureau. Hartt was a capable-looking man, more intelligent in appearance than the average coroner, and of alert and energetic manners. He spoke to Doctor Van Sutton and the bridegroom, and then addressed himself mainly to the uncle of the bride.

“Have you any knowledge of who could possibly have done this thing?” he asked of Mr. Swift.

“Not the slightest. My niece hadn’t an enemy in the world, that I am aware of. And yet, I can’t think it could have been an accident.”

“Accident! No! But there’s a devilish crime to be discovered and punished. Who saw the lady fall?”

“Everybody in the front part of the church, I suppose,” answered Mr. Swift “That is, everybody who could see her at all. Of course, as there was such a crowd, the ones behind could not see clearly.”

“Who was nearest to her?” went on Mr. Hartt.

“I was,” said Eileen Randall, quickly; “I was stooping down to arrange her train, for her to walk down the aisle, when she just sank down in a heap.”

“You heard no sound, as of a pistol?”

“No; but that was not strange, if it was one of those silent ones, for the music had just burst forth and the choir was singing, and besides that, the audience had begun to laugh and chatter as they always do after a wedding ceremony is completed.”

“And Miss Moulton—er—Mrs. Bingham made no sound?”

“No scream or anything like that. There was a little queer, gurgling sound in her throat,—but it was involuntary, I’m sure.”

“Do you think she had any idea of who shot her?”

“I have no means of judging that. It was all over in an instant. The fall, I mean. She fell all in a heap,—she didn’t sink down slowly.”

“Death was instantaneous,” said Doctor Endicott, who had been away and returned. “The shot went straight through the temple to the brain.”

“Did you see her fall?” said the Coroner, turning suddenly to Stanford Bingham.

“Eh, what?” said the bridegroom, looking up from the attitude of dejection he had shown ever since the tragedy.

“Did you see your wife fall?” repeated Hartt, looking at him steadily.

“I saw her fall, yes,” replied Bingham, “but at that moment Dr. Van Sutton was speaking to me, congratulating me, in fact, and I was paying attention to him. I felt, rather than saw Ethel fall, and I turned, to see her on the floor. I can’t remember clearly after that,—for the shock unnerved me.”

“Small wonder!” said Eileen, sympathetically, and she looked at Bingham with infinite compassion.

Bob Keene noted the two. As many reporters grow to be, he was almost clairvoyant in his perceptions, and he seemed to sense a sort of telepathic communication between Bingham and the maid of honour.

“And you have no suspicion of the criminal?” went on Mr. Hartt.

“Not the slightest,” returned Bingham. “Indeed, I can scarcely believe there could have been such a crime. Could it have been an accident? Could the shot have been intended for some one else? Myself, for instance. Or any other of the bridal party? How could any one want to kill Ethel?”

Bingham’s face was ghastly. He looked like death, himself. His fingers twisted nervously round each other, and great beads of perspiration formed on his brow. Occasionally he darted a sudden quick glance at the dead form near him and as quickly glanced away again.

“We can’t judge of that,” said the Coroner, “until we know where the shot came from. The bride, of course, stood at your left, Mr. Bingham?”

“Yes,” assented Bingham, but he spoke almost doubtfully, and glanced uncertainly at his left arm.

“Of course she did,” broke in Eileen. “Brides always stand the same way. Ethel was on Mr. Bingham’s left side. As she fell I was practically between them, as I stooped down to arrange her train.”

“Then as the shot is in her right temple, we know it must have been fired by some one on the same side of her as Mr. Bingham was,” declared the Coroner. “That is, it was fired by some one on that side of the church, the east side. Now, to discover how far away the assailant stood. I should judge some several feet; but there are practically no powder marks to be seen, as the bullet entered the brain through a thick roll or puff of hair.”

Doctor Endicott agreed with this conclusion, and the Coroner went on.

“Assuming, then, that the criminal was in the church, it must have been one of the audience, or one of the bridal group.”

“Oh, Mr. Hartt,” cried Eileen, “it couldn’t have been one of the bridal party! How can you suggest such a thing?”

“It is not for any one to say what could or could not have been except as it is proved to us by evidence. Granting this horrible crime there must be a criminal, and we must seek him wherever the evidence points. It is difficult to see how a member of the audience could have fired the shot unseen, but we must believe that it was done, for there is no alternative. What we must get at first, is the distance and direction of the hand that held the revolver.”

“And the motive,” put in Mr. Swift. “What could be the motive for the shooting of a young and lovely girl at her wedding altar?”

“There are not many motives for murder,” began the Coroner, thoughtfully. “Could it have been robbery? Is anything missing?”

Eileen gave a sudden exclamation. “There is!” she said; “Ethel’s pendant is gone! Her great diamond!”

Bingham started out of his reverie. He gave a quick glance at the fair white throat of his bride, and said, “So it is! Her diamond is gone!”

“Was it a valuable gem?” asked Hartt.

“Very,” said Eileen, as Bingham did not make any reply. “It was a priceless stone, worthy of a princess. It hung by the slenderest chain of fine platinum links, and now it is gone!”

“Absurd!” said Mr. Swift. “If the jewel is gone, it is because it slipped off when she fell. No sane human being would or could shoot a bride to steal her jewels! Such a theory is untenable.”

“I think so, too,” agreed Bingham. “The slight chain probably broke when she fell, and the stone either slipped down into her clothing or it has dropped to the floor. It is of no consequence in view of the greater crime.”

“Not comparatively, of course,” said the Coroner, “but this matter should be looked into. The theft of the jewel may be a clue.”

“If it was a theft,” repeated Bingham. “I don’t believe the gem is stolen. It must have fallen off accidentally.”

“Let us go and look in the church,” said Eileen, rising.

Whereupon several of them went back into the church, deserted now, save for the sexton, who was sitting in the end of one of the forward pews.

Questioned, he said he had not swept up or in any way disturbed the space about the pulpit where the bridal party had stood.

But careful search showed no trace of the diamond or the little chain. It might be found on the bride’s person, or it might never be found. Stanford Bingham showed not the slightest interest in the matter, but both Mr. Swift and Eileen were greatly worried about it.

“I’m sure Ethel was shot for that reason,” said the girl; “some horrible criminal was clever enough to kill her, and then afterward, in the flurry and excitement, he could get near enough to steal the diamond unobserved. That must be the solution of the mystery, for what other is there? Nobody could have any other reason for killing Ethel.”

The Coroner pondered. It was far-fetched and well-nigh impossible that it should be as Eileen assumed, and yet, as she said, what other theory could be advanced?

“It’s a most baffling case,” he said at last “There are no clues, there is no one to suspect, there are no witnesses,—that is, no one who knows anything definite,—and yet there were hundreds of witnesses!”

Then the detective who had come with the Coroner spoke. “It seems to me,” he said, slowly, “that we are getting nowhere.”

“Because there’s nowhere to get,” grumbled the Coroner.

“But let us think it out,” went on Mr. Ferrall, the detective; “we know the shot was fired from the east side of the church; that is, from some one who stood on the right side of the bride, but we do not know that that some one was in the church. The windows are all open, might not the murderer have stood outside and fired through the window?”

“Good wotk!” said Inspector Kinney; “that’s the first glimmer of light I’ve seen. It’s much more likely that’s the truth, than that one of the audience could do it, unobserved by his near neighbours.”

Coroner Hartt looked dubious and a little sulky. He was angry that he hadn’t thought of it himself.

“In that case,” he said, “we’ve got to look for a regular crook. Some of the well-known professionals. Only such a one would dare anything so dangerous to pull off.”

“I don’t believe the shot was fired through the window,” said Mr. Swift. “It’s too far away and, too, the windows are too high. No one could fire through them without standing up on something, and then he would have been seen.”

“The windows are high,” agreed the detective, “but they are banked up on the outside where vines are planted. I’m not sure, it must be investigated, but I think a man could easily shoot through that front window on the east side.”

“It was that window, if any,” said Mr. Swift, thoughtfully. “If so, wouldn’t there be footprints, or some evidence?”

“Ought to be,” said Ferrall; “I’ll go and have a look.”

He left the group and went out of the church by its front door and made his way around to the window in question.

“A fool’s errand,” said the Coroner; “that shot was fired at closer range than the window. It was the work of some clever crook who was in the audience, dressed like a gentleman, and who, with an automatic pistol, committed the deed, while everybody was looking at the bride, and he was unnoticed. Then, later, in the excitement, he mingled with the crowd around the body, and managed to get the diamond,—also unobserved.”

“There wasn’t any crowd around the body except our own people,” said Mr. Swift. “If any stranger had come near Ethel, I should have noticed him. You didn’t see any one, Eileen?”

“No; no one but our own crowd. However, I was so overcome and almost crazy, I doubt if I should have noticed any one.”

“But I know there were no strangers near Ethel,” went on Mr. Swift. “I tried to go to her when she fell, but I seemed paralyzed with shock and fright. Then Warren went to her, and he cried out, ‘She’s shot!’ and then the others closed in around her, but they were only the bridesmaids, and ushers, I am sure. You saw no one, did you, Doctor Van Sutton?”

“No one but the ones who were there all through the ceremony,” replied the minister. “Then the organist and several of the choir came down. If any stranger was about, they would know it, for they saw it all from the choir loft, and could tell better than we, who were down on the floor.”

“I’m sure we shall find the jewel on the body,” said Bingham. “When can we take it away, Mr. Hartt?”

“I think you can take it any time now, sir. So far as this inquiry is concerned, I think we can find out no more at present. If you desire, Mr. Bingham,—or, Mr. Swift,—you may remove the body at once.”

“It must be taken to my home, of course,” said Everson Swift, with a deep sigh.

Stanford Bingham seemed about to speak, and then thought better of it, for he said nothing, but he looked unutterably agonized and helpless.

“Shall I telephone for an undertaker, Mr. Swift?” suggested Bob Keene, moved to do anything he could to help.

“Yes, if you will,” and Mr. Swift showed relief at being released from that sad duty.

And then Doctor Van Sutton returned to the room where lay all that was mortal of the beautiful bride, and the others prepared to go home.

III - A Few Bars of Music

KEENE ran across the street to telephone, and returned just as Detective Ferrall was going back into the church.

The group near the pulpit, not yet dispersed, asked Ferrall of his search.

“Footprints by dozens,” he replied. “All over the ground, under every window. The windows are too high to look in at, but there are old boxes and benches beneath them. You see, there were any number of curiosity-seekers who couldn’t get into the church, but who wanted to see the show. There must have been several peepers at each window.”

“Perhaps some of them could tell of the shooting,” suggested Keene; “they would have a better view than those inside.”

“There was nothing to see,” said Ferrall, decidedly; “I haven’t a doubt the deed was done with one of those new automatics. They’re hammerless, and the pocket model, as they call it, is tiny. Why, the whole affair is only about four inches long. A man can hold it in his hand, absolutely unseen. And he can discharge it from his pocket, or from under a handkerchief or any concealing material. They’re dead easy to aim, and they make almost no sound and practically no smoke.”

“That must have been the way of it,” said Stanford Bingham, “yet, even granting all that you say, how could any one hit Ethel from a distance, with other people in between?”

“He watched his chance,” said the detective, “and shot when the opportunity presented itself. And I’m not sure he was so far away as we think. The appearance of the wound is not an infallible indication of the distance from which the pistol was fired, since her thick hair allowed no trace of powder marks.”

Just then Warren Swift returned. “I think you’d better go home, father,” he said to the elder Swift. “Mother is pretty well broken up, the house all decorated, you know, and those caterers all about,—oh, it’s awful!”

“Yes, yes, Warry; I’ll go. I suppose I can’t do anything here?”

“No, Mr. Swift,” said Inspector Kinney. “The undertaker will attend to the removal of the body, and bring it to your home. You had better go there to receive it.”

With bowed head, Everson Swift turned to leave the church. To walk back along the aisle up which he had so short a time before led his beautiful niece, in all the panoply of her wedding array! All were silent at the tragedy of it, and Eileen bowed her head in her hands and wept.

The bridegroom touched her arm, lightly. “You’d better go home, dear,” he said, in a low tone.

Eileen looked up with frightened eyes. “Don’t,” she whispered; “oh, Stanford, don’t!”

Bingham stepped hastily back from the girl, but not before the quick eye of the detective had caught his expression of solicitude and the tender note in his voice.

“Is Mr. Swift here?” said the undertaker’s assistant, coming in from the parlour.

“No,” said Warren, “he’s gone home. What is it?”

“Why, here’s a paper that we found in the lady’s glove. We thought you ought to have it.”

“In her glove?” said Warren, as he took the paper.

“Yes, sir, it was folded small and stuffed into her right-hand glove.”

“Let me see it,” said Bingham, and the man handed it over to him.

The detective watched closely, and saw a small slip of paper containing a few bars of instrumental music, with no accompanying words.

“A memorandum for the organist?” asked Ferrall, looking at the music.

“I hardly think so,” returned Bingham, studying the paper. “I’m not very musical, but I’m sure this is no music for the organ or choir.”

“Let me see,” said Eugene Hall, the one of the choristers who had asked to remain. “No, that’s no music for to-day’s use. Maybe it’s a talisman, or something. You know brides often have superstitions about carrying good-luck omens.”

Remembering the fate that had overtaken the bride, a shudder passed over all who heard.

“Give it to me,” said Eileen; “it is no doubt something of that sort. I’ll keep it.”

She put it away in her own glove, when the sexton volunteered information.

“I gave that to Miss Moulton,” he said.

“You did!” exclaimed the detective. “When?”

“In the vestibule, just before she was married. Doctor Van Sutton gave it to me, before that, and told me to be sure to hand it to the bride before she started to march down the aisle.”

“How extraordinary!” said the bridegroom. “Why did he do that?”

“I don’t know, sir, I’m sure.”

“I’ll ask him,” said Ferrall; “it may be an important clue!”

In response to a summons, Doctor Van Sutton came in from the parlour.

“Yes,” he said, “I gave that to John, just as he says.”

“Where did it come from?” asked Bingham.

“It came to me in the morning’s mail,” replied the minister; “it was enclosed in a letter asking me to see that the bride received it just before she started to walk up the aisle. Of course, I did as requested, and I told John to give it to Miss Moulton in the vestibule. I assumed it was a message of good luck, or something like that from a friend.”

“Doubtless that is what it is,” said Eileen; “I shall keep it as a souvenir.”

But Ferrall was not quite satisfied. “Was the letter signed, Doctor Van Sutton?” he asked.

“No, it was not. I don’t usually take notice of anonymous notes, but this seemed different. Surely there can be no harm in it?”

“No; I don’t see how there can be, and yet it was a queer circumstance.” The detective shook his head, uncertainly. .