3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Swish

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

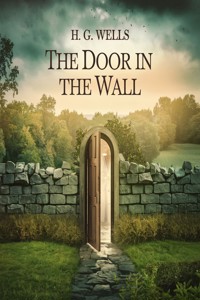

The Door in the Wall is a poignant and thought-provoking short story by H.G. Wells, first published in 1906. It tells the tale of Lionel Wallace, a man torn between his worldly ambitions and the haunting memory of a mysterious door that led to an enchanted garden. This beautifully written story explores themes of nostalgia, lost opportunities, and the tension between imagination and reality.

H.G. Wells masterfully blends elements of fantasy and psychological depth to create a timeless narrative that resonates with readers of all generations. Perfect for fans of classic literature, this edition has been carefully formatted for digital reading while preserving the original text.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Contents

Table of Contents 2

THE DOOR IN THE WALL. 3

by H. G. Wells 3

THE DOOR IN THE WALL. 5

The Door in the Wallby H. G. Wells

First Published: 1906

This version has been formatted for digital publication without altering the original text.

This eBook is independently formatted from the original public domain text of The Door in the Wall by H. G. Wells.

“This edition has been formatted to improve readability on digital devices, preserving the original text.”

I confirm that this eBook, titled The Door in the Wall, contains only the original text written by H. G. Wells, which is in the public domain worldwide.

No additional copyrighted materials, such as images, annotations, forewords, or other supplementary content, have been included. The formatting and layout adjustments have been applied solely to enhance readability on digital devices without altering the original text.

THE DOOR IN THE WALL.

by H. G. Wells

THE DOOR IN THE WALL.

One confidential evening, not three months ago, Lionel Wallace told me this story of the Door in the Wall. And at the time I thought that so far as he was concerned it was a true story.

He told it me with such a direct simplicity of conviction that I could not do otherwise than believe in him. But in the morning, in my own flat, I woke to a different atmosphere, and as I lay in bed and recalled the things he had told me, stripped of the glamour of his earnest slow voice, denuded of the focussed, shaded table light, the shadowy atmosphere that wrapped about him and me, and the pleasant bright things, the dessert and glasses and napery of the dinner we had shared, making them for the time a bright little world quite cut off from everyday realities, I saw it all as frankly incredible. "He was mystifying!" I said, and then: "How well he did it!... It isn't quite the thing I should have expected him, of all people, to do well."

Afterwards as I sat up in bed and sipped my morning tea, I found myself trying to account for the flavour of reality that perplexed me in his impossible reminiscences, by supposing they did in some way suggest, present, convey—I hardly know which word to use—experiences it was otherwise impossible to tell.

Well, I don't resort to that explanation now. I have got over my intervening doubts. I believe now, as I believed at the moment of telling, that Wallace did to the very best of his ability strip the truth of his secret for me. But whether he himself saw, or only thought he saw, whether he himself was the possessor of an inestimable privilege or the victim of a fantastic dream, I cannot pretend to guess. Even the facts of his death, which ended my doubts for ever, throw no light on that.

That much the reader must judge for himself.

I forget now what chance comment or criticism of mine moved so reticent a man to confide in me. He was, I think, defending himself against an imputation of slackness and unreliability I had made in relation to a great public movement, in which he had disappointed me. But he plunged suddenly. "I have," he said, "a preoccupation——

"I know," he went on, after a pause, "I have been negligent. The fact is— it isn't a case of ghosts or apparitions—but—it's an odd thing to tell of, Redmond—I am haunted. I am haunted by something—that rather takes the light out of things, that fills me with longings..."

He paused, checked by that English shyness that so often overcomes us when we would speak of moving or grave or beautiful things. "You were at Saint Aethelstan's all through," he said, and for a moment that seemed to me quite irrelevant. "Well"—and he paused. Then very haltingly at first, but afterwards more easily, he began to tell of the thing that was hidden in his life, the haunting memory of a beauty and a happiness that filled his heart with insatiable longings, that made all the interests and spectacle of worldly life seem dull and tedious and vain to him.

Now that I have the clue to it, the thing seems written visibly in his face. I have a photograph in which that look of detachment has been caught and intensified. It reminds me of what a woman once said of him—a woman who had loved him greatly. "Suddenly," she said, "the interest goes out of him. He forgets you. He doesn't care a rap for you—under his very nose..."