0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: REA Multimedia

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

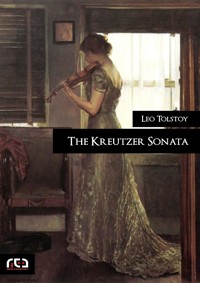

The Kreutzer Sonata is a novella by Leo Tolstoy, named after Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata. The novella was published in 1889, and was promptly censored by the Russian authorities. The work is an argument for the ideal of sexual abstinence and an in-depth first-person description of jealous rage. The main character, Pozdnyshev, relates the events leading up to his killing of his wife: in his analysis, the root causes for the deed were the "animal excesses" and "swinish connection" governing the relation between the sexes.

During a train ride, Pozdnyshev overhears a conversation concerning marriage, divorce and love. When a woman argues that marriage should not be arranged but based on true love, he asks "what is love?" and points out that, if understood as an exclusive preference for one person, it often passes quickly. Convention dictates that two married people stay together, and initial love can quickly turn into hatred.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Leo Tolstoy

The Kreutzer Sonata

Table of contents

COPYRIGHT

TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE.

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

CHAPTER XIV.

CHAPTER XV.

CHAPTER XVI.

CHAPTER XVII.

CHAPTER XVIII.

CHAPTER XIX.

CHAPTER XX.

CHAPTER XXI.

CHAPTER XXII.

CHAPTER XXIII.

CHAPTER XXIV.

CHAPTER XXV.

CHAPTER XXVI.

CHAPTER XXVII.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

LESSON OF “THE KREUTZER SONATA.”

COPYRIGHT

Cover image: Joseph DeCamp, The Violin, 1911

© 2024 REA Multimedia

Via S. Agostino 15

67100 L’Aquila

All Rights Reserved

www.reamultimedia.it

www.facebook.com/reamultimedia

Translated by Benj. R. Tucker

TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE.

On comparing with the original Russian some English translations of Count Tolstoy’s works, published both in this country and in England, I concluded that they were far from being accurate. The majority of them were retranslations from the French, and I found that the respective transitions through which they had passed tended to obliterate many of the beauties of the Russian language and of the peculiar characteristics of Russian life. A satisfactory translation can be made only by one who understands the language and spirit of the Russian people. As Tolstoy’s writings contain so many idioms it is not an easy task to render them into intelligible English, and the one who successfully accomplishes this must be a native of Russia, commanding the English and Russian languages with equal fluency.

The story of “Ivan the Fool” portrays Tolstoy’s communistic ideas, involving the abolition of military forces, middlemen, despotism, and money. Instead of these he would establish on earth a kingdom in which each and every person would become a worker and producer. The author describes the various struggles through which three brothers passed, beset as they were by devils large and small, until they reached the ideal state of existence which he believes to be the only happy one attainable in this world.

On reading this little story one is surprised that the Russian censor passed it, as it is devoted to a narration of ideas quite at variance with the present policy of the government of that country.

“A Lost Opportunity” is a singularly true picture of peasant life, which evinces a deep study of the subject on the part of the writer. Tolstoy has drawn many of the peculiar customs of the Russian peasant in a masterly manner, and I doubt if he has given a more comprehensive description of this feature of Russian life in any of his other works. In this story also he has presented many traits which are common to human nature throughout the world, and this gives an added interest to the book. The language is simple and picturesque, and the characters are drawn with remarkable fidelity to nature. The moral of this tale points out how the hero Ivan might have avoided the terrible consequences of a quarrel with his neighbor (which grew out of nothing) if he had lived in accordance with the scriptural injunction to forgive his brother’s sins and seek not for revenge.

The story of “Polikushka” is a very graphic description of the life led by a servant of the court household of a certain nobleman, in which the author portrays the different conditions and surroundings enjoyed by these servants from those of the ordinary or common peasants. It is a true and powerful reproduction of an element in Russian life but little written about heretofore. Like the other stories of this great writer, “Polikushka” has a moral to which we all might profitably give heed. He illustrates the awful consequences of intemperance, and concludes that only kind treatment can reform the victims of alcohol.

For much valuable assistance in the work of these translations, I am deeply indebted to the bright English scholarship of my devoted wife.

CHAPTER I.

Travellers left and entered our car at every stopping of the train. Three persons, however, remained, bound, like myself, for the farthest station: a lady neither young nor pretty, smoking cigarettes, with a thin face, a cap on her head, and wearing a semi-masculine outer garment; then her companion, a very loquacious gentleman of about forty years, with baggage entirely new and arranged in an orderly manner; then a gentleman who held himself entirely aloof, short in stature, very nervous, of uncertain age, with bright eyes, not pronounced in color, but extremely attractive,—eyes that darted with rapidity from one object to another.

This gentleman, during almost all the journey thus far, had entered into conversation with no fellow-traveller, as if he carefully avoided all acquaintance. When spoken to, he answered curtly and decisively, and began to look out of the car window obstinately.

Yet it seemed to me that the solitude weighed upon him. He seemed to perceive that I understood this, and when our eyes met, as happened frequently, since we were sitting almost opposite each other, he turned away his head, and avoided conversation with me as much as with the others. At nightfall, during a stop at a large station, the gentleman with the fine baggage—a lawyer, as I have since learned—got out with his companion to drink some tea at the restaurant. During their absence several new travellers entered the car, among whom was a tall old man, shaven and wrinkled, evidently a merchant, wearing a large heavily-lined cloak and a big cap. This merchant sat down opposite the empty seats of the lawyer and his companion, and straightway entered into conversation with a young man who seemed like an employee in some commercial house, and who had likewise just boarded the train. At first the clerk had remarked that the seat opposite was occupied, and the old man had answered that he should get out at the first station. Thus their conversation started.

I was sitting not far from these two travellers, and, as the train was not in motion, I could catch bits of their conversation when others were not talking.

They talked first of the prices of goods and the condition of business; they referred to a person whom they both knew; then they plunged into the fair at Nijni Novgorod. The clerk boasted of knowing people who were leading a gay life there, but the old man did not allow him to continue, and, interrupting him, began to describe the festivities of the previous year at Kounavino, in which he had taken part. He was evidently proud of these recollections, and, probably thinking that this would detract nothing from the gravity which his face and manners expressed, he related with pride how, when drunk, he had fired, at Kounavino, such a broadside that he could describe it only in the other’s ear.

The clerk began to laugh noisily. The old man laughed too, showing two long yellow teeth. Their conversation not interesting me, I left the car to stretch my legs. At the door I met the lawyer and his lady.

“You have no more time,” the lawyer said to me. “The second bell is about to ring.”

Indeed I had scarcely reached the rear of the train when the bell sounded. As I entered the car again, the lawyer was talking with his companion in an animated fashion. The merchant, sitting opposite them, was taciturn.

“And then she squarely declared to her husband,” said the lawyer with a smile, as I passed by them, “that she neither could nor would live with him, because” . . .

And he continued, but I did not hear the rest of the sentence, my attention being distracted by the passing of the conductor and a new traveller. When silence was restored, I again heard the lawyer’s voice. The conversation had passed from a special case to general considerations.

“And afterward comes discord, financial difficulties, disputes between the two parties, and the couple separate. In the good old days that seldom happened. Is it not so?” asked the lawyer of the two merchants, evidently trying to drag them into the conversation.

Just then the train started, and the old man, without answering, took off his cap, and crossed himself three times while muttering a prayer. When he had finished, he clapped his cap far down on his head, and said:

“Yes, sir, that happened in former times also, but not as often. In the present day it is bound to happen more frequently. People have become too learned.”

The lawyer made some reply to the old man, but the train, ever increasing its speed, made such a clatter upon the rails that I could no longer hear distinctly. As I was interested in what the old man was saying, I drew nearer. My neighbor, the nervous gentleman, was evidently interested also, and, without changing his seat, he lent an ear.

“But what harm is there in education?” asked the lady, with a smile that was scarcely perceptible. “Would it be better to marry as in the old days, when the bride and bridegroom did not even see each other before marriage?” she continued, answering, as is the habit of our ladies, not the words that her interlocutor had spoken, but the words she believed he was going to speak. “Women did not know whether they would love or would be loved, and they were married to the first comer, and suffered all their lives. Then you think it was better so?” she continued, evidently addressing the lawyer and myself, and not at all the old man.

“People have become too learned,” repeated the last, looking at the lady with contempt, and leaving her question unanswered.

“I should be curious to know how you explain the correlation between education and conjugal differences,” said the lawyer, with a slight smile.

The merchant wanted to make some reply, but the lady interrupted him.

“No, those days are past.”

The lawyer cut short her words:—

“Let him express his thought.”

“Because there is no more fear,” replied the old man.

“But how will you marry people who do not love each other? Only animals can be coupled at the will of a proprietor. But people have inclinations, attachments,” the lady hastened to say, casting a glance at the lawyer, at me, and even at the clerk, who, standing up and leaning his elbow on the back of a seat, was listening to the conversation with a smile.

“You are wrong to say that, madam,” said the old man. “The animals are beasts, but man has received the law.”

“But, nevertheless, how is one to live with a man when there is no love?” said the lady, evidently excited by the general sympathy and attention.

“Formerly no such distinctions were made,” said the old man, gravely. “Only now have they become a part of our habits. As soon as the least thing happens, the wife says: ‘I release you. I am going to leave your house.’ Even among the moujiks this fashion has become acclimated. ‘There,’ she says, ‘here are your shirts and drawers. I am going off with Vanka. His hair is curlier than yours.’ Just go talk with them. And yet the first rule for the wife should be fear.”

The clerk looked at the lawyer, the lady, and myself, evidently repressing a smile, and all ready to deride or approve the merchant’s words, according to the attitude of the others.

“What fear?” said the lady.

“This fear,—the wife must fear her husband; that is what fear.”

“Oh, that, my little father, that is ended.”

“No, madam, that cannot end. As she, Eve, the woman, was taken from man’s ribs, so she will remain unto the end of the world,” said the old man, shaking his head so triumphantly and so severely that the clerk, deciding that the victory was on his side, burst into a loud laugh.

“Yes, you men think so,” replied the lady, without surrendering, and turning toward us. “You have given yourself liberty. As for woman, you wish to keep her in the seraglio. To you, everything is permissible. Is it not so?”

“Oh, man,—that’s another affair.”

“Then, according to you, to man everything is permissible?”

“No one gives him this permission; only, if the man behaves badly outside, the family is not increased thereby; but the woman, the wife, is a fragile vessel,” continued the merchant, severely.

His tone of authority evidently subjugated his hearers. Even the lady felt crushed, but she did not surrender.

“Yes, but you will admit, I think, that woman is a human being, and has feelings like her husband. What should she do if she does not love her husband?”

“If she does not love him!” repeated the old man, stormily, and knitting his brows; “why, she will be made to love him.”

This unexpected argument pleased the clerk, and he uttered a murmur of approbation.

“Oh, no, she will not be forced,” said the lady. “Where there is no love, one cannot be obliged to love in spite of herself.”

“And if the wife deceives her husband, what is to be done?” said the lawyer.

“That should not happen,” said the old man. “He must have his eyes about him.”

“And if it does happen, all the same? You will admit that it does happen?”