33,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: AutoClassic

- Sprache: Englisch

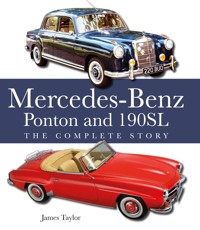

The Pontons may have been Mercedes-Benz's bread-and-butter models of the 1950s, but they were vitally important in establishing the marque as a significant player around the globe. Alongside the saloons that made Mercedes famous world-wide for long-lasting and economical taxis, there were exotic two-door cabriolet and coupé derivatives, and the cars' basic structure was made available too for conversion into ambulances, pick-ups, estate cars and hearses. Not always appreciated is that the 190SL sports model was also derived from the engineering of the Ponton range. The Ponton Mercedes and the 190SL have long enjoyed a strong enthusiast following around the world. Here is their story, from their creation at a time when Mercedes was emerging from the devastation of war, though their success during the German Economic Miracle of the 1950s, to their final days in the early 1960s alongside the first of the 'Fintail' models that would eventually replace them. No enthusiast of these widely respected cars will want to be without this book.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 292

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

TITLES IN THE CROWOOD AUTOCLASSICS SERIES

Alfa Romeo 105 Series Spider

Alfa Romeo 916 GTV & Spider

Alfa Romeo 2000 and 2600

Alfa Romeo Alfasud

Alfa Romeo Spider

Aston Martin DB4, 5, 6

Aston Martin DB7

Aston Martin V8

Austin Healey

Austin Healey Sprite

BMW E30

BMW M3

BMW M5

BMW Classic Coupes 1965–1989

BMW Z3 and Z4

Citroën Traction Avant

Classic Jaguar XK – The Six-Cylinder Cars

Ferrari 308, 328 & 348

Frogeye Sprite

Ginetta: Road & Track Cars

Jaguar E-Type

Jaguar F-Type

Jaguar Mks 1 & 2, S-Type & 420

Jaguar XJ-S

Jaguar XK8

Jensen V8

Land Rover Defender 90 & 110

Land Rover Freelander

Lotus Elan

Lotus Elise & Exige 1995–2020

MGA

MGB

MGF and TF

Mazda MX-5

Mercedes-Benz Fintail Models

Mercedes-Benz S-Class 1972–2013

Mercedes SL Series

Mercedes-Benz SL & SLC 107 Series

Mercedes-Benz Saloon Coupé

Mercedes-Benz Sport-Light Coupé

Mercedes-Benz W114 and W115

Mercedes-Benz W123

Mercedes-Benz W124

Mercedes-Benz W126 S-Class 1979–1991

Mercedes-Benz W201 (190)

Mercedes W113

Morgan 4/4: The First 75 Years

Peugeot 205

Porsche 924/928/944/968

Porsche Boxster And Cayman

Porsche Carrera – The Air-Cooled Era

Porsche Carrera – The Water-Cooled Era

Porsche Air-Cooled Turbos 1974–1996

Porsche Water-Cooled Turbos 1979–2019

Range Rover First Generation

Range Rover Second Generation

Range Rover Third Generation

Range Rover Sport 2005–2013

Reliant Three-Wheelers

Riley – The Legendary RMs

Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud

Rover 75 and MG ZT

Rover 800 Series

Rover P5 & P5B

Rover P6: 2000, 2200, 3500

Rover SDI

Saab 92–96V4

Saab 99 and 900

Shelby and AC Cobra

Subaru Impreza WRX & WRX ST1

Sunbeam Alpine and Tiger

Toyota MR2

Triumph Spitfire and GT6

Triumph TR6

Triumph TR7

Volkswagen Golf GTI

Volvo 1800

Volvo Amazon

First published in 2023 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2023

© James Taylor 2023

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 4228 3

Picture Credits

All picture are from the author’s collection with the following exceptions: Bundesarchiv, 18 (bottom); Duhon, 13 (left above); Jeremy/WikiMedia Commons, 91; Magic Car Pics. 43, 44 (all), 89, 94, 102 (top), 108 (all), 133 (right), 141 (top); Peter Olthof/Flickr, 26 (top); Colin Peck, 88 (bottom), 131 (top right, bottom); Lothar Spurzem, 25, 92, (bottom); Schwiki, 115 (top).

Cover design by Design Deluxe

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Timeline

CHAPTER 1 THE LIFE AND TIMES OF THE PONTON MERCEDES

CHAPTER 2 DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

CHAPTER 3 THE 180 AND 190 4-CYLINDER SALOONS

CHAPTER 4 THE DIESEL PONTONS

CHAPTER 5 THE CARBURETTOR 6-CYLINDERS

CHAPTER 6 FLAGSHIP:THE 220SE

CHAPTER 7 COUPÉS AND CABRIOLETS, 1956–1960

CHAPTER 8 A SPORTS DERIVATIVE:THE 190SL

CHAPTER 9 MERCEDES ‘IN ALLER WELT’

CHAPTER 10 DERIVATIVES

CHAPTER 11 PURCHASE AND OWNERSHIP

APPENDIX I PONTON IDENTIFICATION NUMBERS

APPENDIX II OVERALL PRODUCTION FIGURES, 1953–1962

APPENDIX III PAINTS

APPENDIX IV APPENDIX IV FORGOTTEN IDEAS

Index

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Ponton Mercedes may have been the bread-and-butter models of the 1950s, but they were vitally important in establishing the marque as a significant player around the globe. Alongside the saloons that made Mercedes famous worldwide for long-lasting and economical taxis, there were exotic two-door cabriolet and coupé derivatives, and the cars’ basic structure was also made available for conversion into ambulances, pick-ups, estate cars and hearses. Not always appreciated is that the 190SL sports model was also derived from the engineering of the Ponton range, and there is a chapter here devoted specifically to them.

In preparing this book, I am pleased to acknowledge the help of Mercedes-Benz Classic and the Daimler-Benz Media site, both for information and for the majority of the illustrations. Over the years, I have picked up a lot of information from members of the Mercedes-Benz Club in the UK and from its excellent publication, the Gazette, and I have made full use of the material available about the Pontons in German.

Special thanks go to the many photographers who have made their work available for use through WikiMedia Commons, and to Magic Car Pics, who supplied a number of excellent pictures.

James TaylorOxfordshireSeptember 2022

TIMELINE

1953

180 and 180D introduced.

1954

220 introduced.

1956

190 introduced.

219 and 220S replaced 220.

Coupé and Cabriolet models introduced.

1957

180a with M121 engine replaced 180.

1958

190D and 220SE introduced.

1959

180b replaced 180a, 180Db replaced 180D, 190b replaced 190, 190Db replaced 190D.

Fintail models replaced 219, 220S and 220SE.

1961

180c replaced 180b, 180Dc replaced 180Db.

Fintail models replaced 190b and 190Db.

Fintail-derived models replaced coupés and convertibles.

1962

Final Ponton saloons built.

CHAPTER 1

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF THE PONTON MERCEDES

In West Germany, the years immediately after the end of World War II in 1945 were times of hardship and austerity. And yet by the end of the 1940s there were already signs of recovery. Currency reforms in June 1948 made an important contribution, and perhaps the sheer need to return to some kind of normality spurred the nation on to greater efforts. It was in 1950 that The Times newspaper described what was happening as an ‘Economic Miracle’, and that remarkable recovery continued throughout the following decade.

Overseen by Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and his economic minister Ludwig Erhard, the German economy went from strength to strength. Between 1950 and 1957, industrial production doubled, while gross national product grew at a rate of 9 or 10 per cent year upon year. The West German recovery was accelerated by $1.4 billion of American aid granted under the Marshall Plan, and the country gradually began to play an increasingly important role in world affairs. It joined NATO in 1955 and was once again permitted to have a standing army, and in 1958 it became a founding member of the European Economic Community. West German citizens became comfortable and wealthy by comparison with their counterparts elsewhere in Europe.

It was against this background that the Mercedes Ponton saloons were able to become a major success. Unquestionably, their engineering integrity played a major part in this, but it is also beyond doubt that without the West German determination to regain international respect through trade and prosperity, their impact would have been considerably less. Not only did their homely shape become a reassuring symbol that all was once again right with the West German domestic situation, but their enthusiastic acceptance in world markets was in many ways a symbol that the country was returning to its rightful place in the wider world.

It had all been very different in 1945, when Germany had signed an unconditional surrender. The future then looked bleak. Many of the country’s major cities lay in ruins after relentless pounding by the Allied bombing that had been designed to disable the industries that had supported the German war machine. The country had also been divided into four zones of Allied military occupation. There was widespread deprivation and poverty; thousands of people had been displaced, and there were severe shortages of the everyday necessities.

As a major industrial concern, Daimler-Benz had been an important target for that aerial bombing, and its factories had for the most part been reduced to rubble. Three of them, at Mannheim and at Untertürkheim and Sindelfingen near Stuttgart, were now in the American military sector; the Gaggenau truck plant was isolated in the French sector; and the Marienfelde factory in Berlin was rapidly being plundered in the name of war reparations by the Russians, into whose sector it had fallen. The position would later be codified: the Russian military sector would cut itself off from the rest of Germany and would become the German Democratic Republic, or East Germany; and the American, British and French sectors would coalesce into the genuinely democratic West Germany. A statement issued by the Daimler-Benz Board of Directors in 1945 left no-one in any doubt about the impact on the company. ‘At this point,’ it said, ‘the company had practically ceased to exist.’

So when the Untertürkheim factory re-opened its gates one month to the day after the final Allied bombing raid, those gates admitted not the 20,000 employees of its heyday but a skeleton workforce of 1,240 who were permitted under the watchful eye of American troops to do no more than begin the work of clearing the debris and salvaging what they could. The resumption of car production was a distant dream.

Nevertheless, although the occupying powers had no intention of allowing Germany to re-establish its former industrial might, they recognised that the appalling conditions of the post-war nation could only be alleviated if it was permitted to get back onto a sound economic footing. This meant that some kind of industrial life had to begin again, and so when the Daimler-Benz workforce had salvaged what remained of the company’s plant and machinery, it was permitted as a first stage to keep itself busy by undertaking repair and maintenance work on existing vehicles, most of which were operated by the occupying military.

Meanwhile, work began on rebuilding the factories, and little by little some of the old company pride began to return. Despite the difficult winter of 1945–1946, when the factories were denied coal, gas and electricity, by the middle of the following year reconstruction had reached a stage where it was possible to contemplate the limited production of motor vehicles once again. Miraculously, the production machinery for the pre-war 170V saloon, which had lain idle since the Mercedes-Benz car factories had been diverted to war work in 1942, had survived the bombing. These and such parts stocks as had also survived were moved into the Untertürkheim factory, and the Daimler-Benz directors gained permission from the American military commander to start production once again alongside the repair and maintenance work.

The Mercedes factory at Sindelfingen was put out of action by heavy bombing during the Second World War.

Obviously, this production was very limited in the beginning. Raw materials were in short supply, and in 1946 living conditions were so bad that most West Germans were more worried about where their next meal was coming from than about buying a car. It was also true that the occupying powers had agreed in March that German industrial output should not be allowed to exceed roughly half of its 1938 level. As a result, Daimler-Benz were initially permitted to build only such motor vehicles as might be of direct benefit to the nation’s social and economic recovery. Private cars did not fall into this category, and so the Untertürkheim factory produced 170V chassis-cabs – just 214 of them in 1946. They built some up as ambulances in their own body plant, and passed others to a number of small businesses that constructed bodies to turn them into much-needed delivery vans and pick-up trucks.

The devastation extended to the company’s other factories, too. This was the scene at Untertürkheim in 1946.

The first vehicles to be built as production resumed were utility vans and pick-ups based on the 170V chassis; note the black paint instead of chrome plating, which was not available. The flowers and the plaque in the windscreen indicate some kind of celebration – probably this was the 100th vehicle to come from the factory.

As conditions became a little better, so the more draconian regulations imposed by the occupying forces were gradually relaxed. By May 1947 Daimler-Benz was once again given permission to build cars. Of course, these had to be 170V models, because there had been neither the time nor the resources to develop anything new. The customers were primarily those who genuinely needed a car for their work, such as doctors and administrative officials, and the manufacture of chassis-cabs to be turned into commercial utility vehicles continued as well. Production numbers gradually increased: 1,045 examples of the 170V in all its forms were made in 1947, and 5,116 the following year. After December 1948, pressure on Daimler-Benz’s own body plant was relieved when production of the ambulance bodies was farmed out to the Lueg concern in Bochum, and in the meantime the company’s engineers had been working on a series of improvements that would keep Mercedes models saleable as the economy continued to improve.

The two different headlamp sizes on these 170V utilities lined up ready for delivery probably reflected difficulties of supply more than anything else.

Some 170V chassis-cabs were sent to body specialists, such as this one that was bodied as a pick-up by Hägele at Mössingen, near Stuttgart. Bright metal plating had become available again by the time this one was built. Hägele would later build some bodies for Ponton derivatives.

So it was that Daimler-Benz were able to reveal three new models at the Hanover Fair that opened on 18 May 1949. One was their first all-new post-war truck, the L3500, and the other two were new saloon cars called the 170D and the 170S. In practice, all that was really new about the 170D was its engine, a diesel derivative of the 170V’s petrol engine that picked up on Mercedes’ pioneering work with diesels in the 1930s and provided exactly the right level of fuel efficiency for the times. The 170S, meanwhile, took a tentative step into a higher price bracket and offered a larger body than the 170V and 170D. Much of its design was carried over from the body of the pre-war 6-cylinder 230 model, and its engine was a big-bore derivative of the 170V’s old side-valve 4-cylinder, offering around 37 per cent more power that more than offset the model’s greater weight. Suspension improvements also made clear that the Daimler-Benz engineers were determined to embrace progress as much as their limited resources allowed.

This preserved 170V shows the pre-war style of the saloons that began to come from Mercedes in 1947. The amber flasher lights would not have been part of its original equipment.

Perhaps even more significant was that the 170S saloon was accompanied by cabriolet and coupé models that were built on the same chassis. These were deliberately prestigious cars, within the reach only of the wealthier members of West German society, but they were a statement of intent. They had also been developed with an eye on export markets, because Daimler-Benz was now thinking in terms of overseas sales to ensure the stability of its business and to provide a means for expansion. This policy was certainly in line with the aims of the West German government at the time, and no doubt received its enthusiastic support.

The 170S made the basic 170 shape look more substantial, but it was still fundamentally a pre-war design.

Final car assembly was relocated from Untertürkheim to Sindelfingen in 1950 as factory refurbishment continued apace. New models now began to follow thick and fast. Improved versions of the 170V and 170D were announced in June that year with enlarged and more powerful engines, and additional equipment options began to appear from October 1950, exploring the customers’ appetite for further improvements. The next introductions came in 1952, and were further improvements to the 170V, 170D and 170S, together with a diesel-engined version of the last-named that was called the 170DS. This incremental approach continued until mid-1953, when the last examples of the old 170 range were built.

The legendary Mercedes L3500 truck also played a major part in the company’s revival during the early 1950s. It was an extremely adaptable design that was used for many roles.

In the meantime, Mercedes had given two more very clear indications of its return to strength. In April 1951, it had introduced a new 6-cylinder engine with a modern overhead camshaft design and had put it into models that were essentially cosmetically altered 170S saloons and cabriolets (and a coupé would be introduced later). These were known as 220 models, and with their arrival Mercedes had finished setting out its stall for the next generation of its mainstream cars. The cabriolet and coupé 170S models disappeared, and the range now consisted of 4-cylinder saloons with petrol and diesel engine options, and 6-cylinder saloons with prestigious cabriolet and (from 1954) coupé derivatives. These were the models that the next generation of new Mercedes would have to replace.

The 170S Cabriolet added a little glamour to the range, and for a time was seen as a prestige model.

Determined to lead the pack of German car manufacturers, Mercedes introduced one more new model in September 1951 at the Frankfurt Motor Show. Deliberately aimed at rich businessmen, heads of state and export sales, the 300 saloon was a big luxury model with another new 6-cylinder engine, this time with a full 3 litres of swept volume. In further developed form, that engine would go on to power the even more remarkable 300SL sports racers, and there would also be prestigious cabriolet and coupé luxury derivatives with the name of 300S. The 300 saloon did its job of setting Mercedes above its German rivals on the domestic market when it was adopted as an official car by the German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, and the cars have been known as the Adenauer Mercedes ever since.

Restyled front wings distinguished the 220 with its new 6-cylinder engine, but the overall shape was familiar from the 170S.

The 300 range, however, had no direct relevance to the story of the mainstream Mercedes models. As Chapter 2 explains, their development began in 1951 – before then, the engineers had been working flat-out on the 300 – and they were introduced in the autumn of 1953. These mainstream models were the Pontons, so called by a journalist who suggested that their modern full-width bodies resembled a pontoon float, and it is their story that is told in detail in the rest of this book. By the time of their introduction, the re-organisation and reconstruction of the Mercedes car factories had been completed and the new models would be assembled at Sindelfingen, using engines, gearboxes, axles and other components produced at Untertürkheim, which had also become home to the engineering centre where they had been designed and to the research and development department that had been responsible for their testing and for bringing them to production readiness.

This 220 Cabriolet is a museum piece today. The chrome strakes on the wing tops that incorporated turn indicator lenses previewed a feature of the 220 Ponton models.

The job of the Ponton models was to replace the 4-cylinder 170s and 6-cylinder 220s as the mainstream Mercedes, but it was more than Daimler-Benz could contemplate to replace the whole existing range at a stroke. So some of the old models overlapped with the new ones, remaining in production until it was possible to get all the replacement types into production. There never would be any replacements for the 170V and 170D at the very bottom of the range (although some were planned, as Appendix IV explains); instead, the new Ponton models were always pitched as replacements for the more expensive 170S and 170SD types, and their new model names of 180 and 180D deliberately reflected this approach.

The Mercedes 300 was launched as the flagship of the range in 1951 but, the new overhead-camshaft engine apart, its design still reflected pre-war thinking. This is a rare right-hand-drive car registered in Britain during 1954.

The old 4-cylinder cars were replaced first, and a replacement for the 6-cylinder 220 did not appear until 1954. Customers for the cabriolets and coupé derivatives nevertheless had to wait another two years before Mercedes was ready with them, even though a prototype car was shown at Frankfurt in 1955 as reassurance that the new models were on their way. As always, it was a question of design and production resources: Mercedes could not do everything at once.

It was once again the improving economic conditions of the 1950s that led to further developments of the Ponton range. From 1956, the 180 and 180D were joined by more expensive petrol 190 and diesel 190D types that offered more performance, higher equipment levels and, above all, more prestige in the middle of the range. The range now matched that of the early 1950s when there had been two levels of 4-cylinder models – the plain 170V and 170D and the more expensive 170S and 170DS. Meanwhile, the 6-cylinder range was split into two as a more powerful 220S replaced the 220 and a less expensive 219 offered a 6-cylinder engine at a lower price, just above the 190. In a final evolution, and once again following socio-economic trends, 1958 brought a set of new models with the 220SE name that reflected the new technology of their fuel-injected 6-cylinder engines.

The Ponton bodyshell takes shape on the lines at Sindelfingen. The bodies progressed round the track backwards, or from right to left in this 1957 picture.

Ponton final inspection lines in the Sindelfingen factory, probably around 1954. Most of the cars are 4-cylinder 180 or 180D types, but the row on the left consists of 6-cylinder 220 models.

These, though, were the last major evolutions of the Ponton range. In autumn 1959, the next generation of Mercedes saloons was introduced as the Fintails, and these initially took over from the 6-cylinder cars. Further models were introduced gradually, replacing the 4-cylinder petrol and diesel cars, and the last of the new models were the prestigious cabriolet and coupé derivatives that were announced in 1961. Just as had happened when the Pontons replaced their predecessors, the last variants lingered on into the new era, and the very last Pontons were built in 1962.

This picture was taken in much the same place in 1956. The bright lights between the rows were designed to highlight any flaws in the paint.

Row upon row of brand-new Ponton saloons stand ready for delivery at the Sindelfingen factory in the mid-1950s.

Their success had been quite astounding for their times. Well over half a million examples had been built, most on a highly efficient assembly line in Sindelfingen but many in foreign countries from kits of parts. Factory tour guides in Stuttgart used to say that it took just 1,500 minutes to build a Ponton saloon, although of course the amount of hand-finishing in the cabriolet and coupé models increased the build times of those special models considerably. Among those half a million Pontons, the best sellers had consistently been the diesel models. Though humble in their pretensions, they had become firm favourites as taxis around the world, and this success would dictate the shape of the Mercedes model range for decades in the future.

The Fintail saloons began to replace the Ponton models in 1959. This is an early 220SE model.

DAIMLER-BENZ AND MERCEDES-BENZ

The Daimler-Benz company really came into being as a result of the dramatic inflation that gripped Germany after 1923, although its component parts had been in existence for nearly forty years before that.

Karl Benz spent some time as a young man working for a carriage-builder in Stuttgart before setting up a company to build stationary gas-powered engines in 1883. Keen to combine his two areas of expertise to produce a self-propelled vehicle, he designed a water-cooled four-stroke engine that ran on petrol (which was then mainly used as a cleaning agent) and installed it in a three-wheeled vehicle that first ran in 1885. This is generally acknowledged to have been the world’s first motor car.

Karl Benz created the vehicle considered to be the world’s first motor car and founded the company Benz und Cie.

Gottlieb Daimler made the world’s first petrol-powered internal combustion engine but did not put it into a vehicle until a year after Karl Benz.

Later developments of this idea took Benz’s company, based at Mannheim, into series production of cars and by the end of the 1890s the company had become the world’s leading motor manufacturer, with a production capacity of 600 cars a year. During World War I, Benz und Cie was obliged to focus on trucks and aero engines, but regained its position as a leading car maker when peace returned.

Like Karl Benz, Gottfried Daimler came from the stationary engine industry in Germany. He gained his experience with the Deutz company, and set up on his own in 1882 at Bad Cannstatt. By 1883 he had produced the world’s first petrol-powered internal combustion engine, and in 1886 – a year after Benz’s three-wheeler – he put his engine into a suitably modified horse-drawn carriage. Daimler cars were not produced in any number before 1895, and Daimler himself died in 1900, but the company was by then a thriving concern, with strong sales of marine engines.

Ferdinand Porsche, whose name would later appear on his own cars, was an early Chief Engineer for the Mercedes business.

This 1894 Benz Velo was pictured before the London-to-Brighton veteran car run more than a hundred years later, in 2011.

The workings of an early Benz self-propelled vehicle are seen on this replica of a Benz Velo in the Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart.

At this point, Emil Jellinek began negotiations for the sole agency for Daimler cars in France and in the countries of the Austro-Hungarian empire. To avoid a clash with Panhard-Levassor, who held a licence to build Daimler engines in France, he agreed to name the cars after his daughter, Mercedes. The sales and racing success of the cars called Mercedes were such that in 1902 the Daimler Board decided to adopt the brand name for all its cars. In 1911 the three-pointed star was registered as its trademark and, like the Benz factories, the Daimler ones were turned over to the production of aero engines when war came in 1914.

Mercedes Jellinek, whose name came to be used for cars from the Daimler company.

Although the Mercedes car business resumed after the war (with Ferdinand Porsche as its Chief Engineer from 1922), it soon became clear that Germany’s two biggest car makers could not both expect to survive the post-war recession. Talks followed; in 1924, the first steps were made towards a co-operative merger of the two companies, and in 1926 a full merger was agreed. The new company was established with headquarters in Stuttgart and took the name of Daimler-Benz, while the cars were given the new name of Mercedes-Benz – which they have retained ever since. The shortened and familiar version today is Mercedes, and for convenience that is used in this book.

THE PONTON MODELS

The various model names associated with the Ponton models can be confusing, not least because later developments of some models were given suffix letters that were used within Mercedes-Benz and its service network but were not displayed on the cars.

In addition, and despite the overall similarities within the range, there were four different major bodyshell types. These were distinguished by codes beginning with a W, although once again these codes were not generally used outside the company and its service network. That W prefix appears to have stood for Wagen, or car, although some commentators have suggested it stood for Werksbezeichnung, or factory designation.

Dates shown here relate to calendar-year, and not to model-year.

CHAPTER 2

DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

It is generally agreed that work on a new medium-sized Mercedes-Benz began at the company’s Stuttgart headquarters during 1951. By then, the design studios were free of the new large Mercedes, the 300, which was introduced at the Frankfurt Motor Show in April that year. At the same show, the company presented its latest mid-size model, the 6-cylinder 220 that sat above the 4-cylinder 170 in the range hierarchy. Although there would be further development of all these models over the next few years, the major part of the work was now over. Stuttgart’s designers and engineers could breathe deeply and start to think about their eventual replacements.

Chief Engineer Fritz Nallinger had risen through the ranks, having joined the old Benz company in 1922.

At that stage, the Director of Engineering for the Mercedes marque was Fritz Nallinger. Nallinger had been with the company and its predecessors since the 1920s, and it was part of his brief to run research into the kind of cars that would be needed in the future. By 1951, there were several new ideas floating around within the Engineering Department, many of them resulting from research programmes that Nallinger had put in place after rejoining the company in 1948 following a spell away occasioned by the war.

Karl Wilfert was in charge of body development, and as part of that function he oversaw the team that worked on styling.

Another key senior engineer at Stuttgart was Karl Wilfert, who was in charge of body engineering. At that time, this discipline included styling, and the chief stylist working to Wilfert was Friedrich Geiger. Geiger had joined Mercedes-Benz in 1933 in the special vehicle manufacturing department, where he had drawn up the bodies for the legendary 500K and 540K high-performance cars. After a brief period away from Daimler-Benz in the late 1940s, he had rejoined the company as a body engineer (Mercedes then had no other term available for the styling function), and later became the first Mercedes Chief Stylist when the Styling Department was formally established as a separate function in 1955. In the mean time, he was certainly one of the men who influenced the shape of the Ponton saloons.

Friedrich Geiger was responsible for styling, which when the Pontons were designed was not yet a separate department at Mercedes. He was the man behind several top-class Mercedes designs.

Bela Barényi took the lead on safety engineering at Mercedes, and at the time of the Pontons his primary focus was on structural integrity. The Pontons incorporated some of his ideas, but the full crash-safety structure had to wait for the next generation of Mercedes saloons.

Also reporting to Karl Wilfert were the safety engineers headed by Bela Barényi. As the panel on page 23 explains, Barényi would later be responsible for the concept of the crumple zone that would represent a huge step forward in automotive safety. This arrived a little too late to affect the design of the new Mercedes saloons, but the bodyshell was designed with a special focus on structural rigidity, which Barényi’s earlier pioneering studies had demonstrated to be an important factor in an accident.

The old and the new: an early 180 stands next to an outgoing 170SV for comparison.

Shapes and structures were both critical considerations when work began on the new medium-sized Mercedes. The existing medium-sized cars could trace their appearance back to the middle of the 1930s and, despite the introduction of more rounded shapes on their 1951 iterations, still featured what was essentially pre-war styling with separate wings and running-boards. The late 1940s had seen some major changes in bodywork design, primarily pioneered by American manufacturers: bodies now covered the full width of the chassis, leaving no room for running-boards or voluminous wings, and increasingly influential was the ‘three-box’ styling pioneered by industrial designer Raymond Loewy and stylist Virgil Exner on the 1947-model Studebakers. This balanced the projecting bonnet with a projecting boot, and gave cars a very different appearance from the typical designs of the 1930s.

On the structural side, important changes had begun before the war as unitary structures (often called monocoques in Europe) had been developed to replace body-on-chassis structures. Mostly confined to smaller cars, their multiple advantages included lighter weight, simpler manufacture, and the possibility of lower and less wind-resistant lines. In 1951, all the existing Mercedes-Benz models had body-on-chassis construction, including the latest 220 and 300 saloons, but Nallinger had already initiated studies into chassis-less construction. On the one hand, his engineers were beginning to look at exotic methods such as the tubular space-frame that would eventually form the basis of the 300SL models. On the other, they were looking at unitary construction for the everyday, volume-production cars. An important avenue of enquiry was how to integrate Barényi’s safety ideas into one of the new unitary shells.

These were major engineering programmes, and the amount of resources they consumed must have had an influence on the decisions to carry over existing components as far as possible in other areas of the cars. The programme came together with the internal code name of W120, W standing for Wagen or car and the 120 simply being a serial number that may well have been chosen at random (Mercedes did not number its car programmes sequentially, although related programmes often had adjacent numbers).

Fortunately, the existing suspension designs were reasonably satisfactory and could be adapted relatively easily to suit a unitary bodyshell. At the front, the existing design of independent suspension depended on unequal-length wishbones with coil springs and an anti-roll bar. At the rear, Mercedes cars had for many years used swing-axles, with each half of the axle pivoting separately from a differential anchored to the chassis. This arrangement had some known disadvantages, including a tendency for a wheel to jack up under hard cornering and cause the rear end to break traction, but it was good enough in everyday driving. For the new models, the differential housing would be mounted to the underside of the shell through a sound-deadening block, and rubber bushes would be used on the radius arms.

Even the latest Mercedes models introduced in 1951 had a central chassis lubrication system, but this again was now seen as old-fashioned and was increasingly being replaced by a servicing requirement for regular greasing at key points. This trend would also influence the design of the W120 range. As for the steering, the recirculating-ball type that was already in production had the advantage of minimising kick-back over bumps and could easily be adapted to the new car.