2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

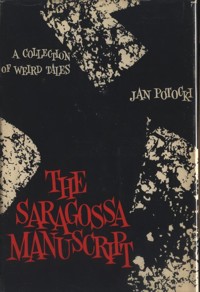

- Herausgeber: Olympia Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

This is an extraordinary collection of tales that is sure to appeal to all readers of the weird and supernatural. Written in French by a Polish nobleman and first published, almost secretly, in St. Petersburg in 1804. During the wars in Spain, an officer of the Walloon Guards finds, in a deserted castle in Saragossa, a manuscript of such absorbing interest that he carries it with him on his campaign. Taken prisoner by the Spaniards, he falls into the hands of a Spanish officer who claims that the manuscript belonged to his family. The Spaniard proceeds to dictate to his prisoner, now an honored guest in the officer's house, the remaining stories in this collection.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

The Saragossa Manuscript

Jan Potocki

This page copyright © 2009 Olympia Press.

The first day

Count d'Olavidez had not yet established foreign settlements in the Sierra Morena—that lofty chain of mountains that separates Andalusia from La Mancha—which was at that time inhabited solely by smugglers, bandits and a few gypsies who had the reputation of eating the travelers they murdered, whence the source of the Spanish proverb: Las Gitanas de Sierre Morena quieren carne de hombres.

That is not all. It was said that the traveler who ventured into that wild region was assailed by a thousand terrors that would freeze the blood of the boldest man. He heard wailing voices mingled with thundering torrents and howling storms; false lights led him astray, and invisible hands pushed him towards the edge of bottomless precipices.

There were, it is true, a few ventas, or lonely inns, scattered along that disastrous road, but ghosts, more diabolical than the innkeepers themselves, had forced the latter to yield the place to them and retire to regions where their rest was troubled only by twinges of conscience—the sort of phantom that innkeepers know how to deal with. The innkeeper of Anduhhar called on St. James of Compostella to witness the truth of these amazing tales. And he added that since the bowmen of St. Hermandad had refused to lead expeditions over the Sierra Morena, the travelers either took the Jaen road or went by way of Estramadura.

I replied that this choice might be all very well for ordinary mortals, but as the king, Don Philip the Fifth, had graciously honored me with the rank of captain in the Walloon Guards, the sacred laws of honor forbade me to take the shortest route to Madrid without inquiring if it were also the most dangerous.

“My lord,” replied my host, “your grace will allow me to point out to him that if the king has honored him with a company of Guards before age has honored your grace's chin with the slightest sign of down, it would be wise to exercise a little caution. Now, I say that when demons take over a region...”

He would have said much more, but I put spurs to my horse and did not draw rein until I was out of reach of his remonstrances. Then looking back, I saw him still waving wildly and pointing to the road to Estramadura in the distance. My valet, Lopez, and Moschito, my zagal, turned piteous eyes on me, as if to repeat the innkeeper's warning. I pretended not to understand, and plunged into the thickets at the point where the settlement known as La Carlota has since been built.

At the very spot where today there is a relay station, there was in those days a shelter, well known to muleteers, who called it “Los Alcornoques”—or the green oaks—because of two beautiful oak trees that spread their shade over a gushing spring as it flowed into a marble watering-trough. It was the only water and the only shade to be found between Anduhhar and the inn, “Venta Quemada.” Though it was built in the middle of a desert, the inn was large and spacious. It was, in reality, an old Moorish castle which the Marquis de Penna Quemada had had repaired; hence the name Venta Quemada. The Marquis had leased it to a citizen of Murcia, who had turned it into the largest hostelry on that route. Travelers left Anduhhar in the morning, dined at Los Alcornoques on provisions they had brought with them, and then slept at Venta Quemada. Sometimes they even spent all the next day there to rest up for the journey over the mountains and to buy fresh provisions. This is what I had planned to do.

But as we came within sight of a clump of green oaks, and I mentioned to Lopez the light meal we counted on having there, I perceived that Moschito was no longer with us; neither was the mule laden with our provisions. Lopez explained that the boy had dropped behind some hundred paces to make some repair to his mount's packsaddle. We waited for him, then rode on a short distance, and halted to wait for him again. We called, we retraced our steps to search for him—but in vain. Moschito had vanished, taking with him our fondest hopes—in other words, our dinner. I was the only one fasting, for Lopez had never stopped nibbling on a Toboso cheese with which he had provided himself, but which, apparently, did nothing to raise his spirits for he kept muttering that the Anduhhar innkeeper had told us so, and devils had certainly carried off poor Moschito.”

When we arrived at Los Alcornoques, I found on the watering-trough a basket, filled with fig leaves, that had probably been full of fruit and had been left behind by some traveler. Out of curiosity I rummaged around in it and had the pleasure of finding four beautiful figs and an orange. I offered Lopez two of the figs, but he refused them, saying he could wait till evening. I therefore ate all the fruit, after which I desired to quench my thirst at the nearby spring. Lopez stopped me, saying that water, taken on top of fruit, would make me ill and that he had a little Alicante wine left. I accepted his offer, but scarcely was the wine in my stomach when I felt a heavy weight oppress my heart. Earth and sky whirled about my head and I would surely have fainted had not Lopez hastened to my aid. He restored me to full consciousness and assured me it was nothing to alarm me, being merely the result of exhaustion and lack of food. And, in truth, not only was I quite myself again, but unusually strong and in an extraordinary state of excitement. The fields seemed to be dotted with the most vivid colors; objects shimmered before my eyes like stars on a summer night and my arteries throbbed wildly, especially in my throat and at my temples.

When he saw that my momentary weakness had had no ill effect, Lopez could not refrain from airing his grievances.

“Alas!” said he, “why did I not go to Fra Heronimo della Trinidad, monk, preacher, confessor and the oracle of our family? He is the brother-in-law of the son-in-law of the sister-in-law of the father-in-law of my mother-in-law and, as he is therefore our closest relative, nothing is done in our family without his advice. It's true he told me the officers of the Walloon Guards were a heretic breed, which is plain to be seen from their light hair, blue eyes and red cheeks, whereas the early Christians are the same color as Our Lady of Atocha, as painted by St. Luke.”

I checked this flow of impertinence by ordering Lopez to hand me my double-barreled gun and to stay with the horses while I climbed a crag in the neighborhood to see if I could find Moschito, or some trace of him. At this Lopez burst into tears and, throwing himself at my feet, implored me, in the name of all the saints, not to leave him alone in such a dangerous place. I offered to stay with the horses and let him go and search, but he seemed to find that alternative even more alarming. I gave him, however, so many good reasons why we must search for Moschito that in the end he let me go. Then he pulled a rosary out of his pocket and began to say his prayers beside the watering-trough.

The heights I intended to scale were farther off than I had judged; it took me nearly an hour to reach them and, once there, I could see nothing but a wild and empty plain. There was no sign of men, animals or habitations, no road but the highroad I had followed and nobody on it—and everywhere, utter silence. I broke it with my shouts and the echoes came back from the distance. At last I gave up and retraced my steps to the watering-trough, where I found my horse tied to a tree, but Lopez—Lopez had vanished.

Two courses were now open to me: to return to Anduhhar or to continue my journey. The first did not even enter my mind. I flung myself on my horse and, putting him to a fast trot, arrived two hours later at the banks of the Guadalquiver which, at that point, is by no means the calm and majestic river that encircles the walls of Sevilla in its stately course. As it emerges from the mountains, the Guadalquiver is a raging torrent without banks or bottom, constantly booming against masses of rocks that impede its progress.

The valley of Los Hermanos begins at the point where the Guadalquiver spreads out over the plain, a valley so-called because three brothers, united less by the ties of consanguinity than by their love of brigandage, had long made it the theatre of their exploits. Of the three brothers, two had been hanged and their bodies could be seen dangling from the gallows at the entrance to the valley. But Zoto, the eldest, had escaped from the prisons of Cordova and was said to have holed up in the mountains of Alpuharras.

Strange tales were told of the two brothers who had been hanged. Though people did not refer to them as ghosts, they declared that at night their bodies, inhabited by I know not what demons, came down from the gallows to harass the living. This was considered to be so true that a theologian from Salamanca wrote a dissertation proving that the two hanged men were a species of vampire, and that one thing was not more incredible than the other, a statement even the most skeptical readily admitted. It was also rumored that the two men were innocent and that, having been unjustly condemned, they were avenging themselves, with heaven's consent, on travelers and other wayfarers. As I had heard much talk of this in Cordova, I was curious to have a closer look at the gallows. The spectacle was all the more disgusting as the hideous cadavers, swaying in the wind, executed the most extraordinary movements, while horrible vultures tore at them and ripped off pieces of their flesh. I averted my eyes in horror and rushed headlong down the mountain road.

I must admit that, as far as I could see, the valley of Los Hermanos seemed well adapted to favor the enterprises of bandits and to serve as their retreat. One was stopped on every hand either by rocks fallen from the cliffs above, or by trees uprooted by storms. In many places, the road crossed the river bed or passed by deep caverns, whose sinister aspect aroused distrust.

Emerging from that valley, I entered another and discovered the venta that was to be my shelter, but which from a distance did not inspire confidence. I could see that it had neither windows nor shutters; no smoke issued from the chimneys; I saw no signs of life around it and heard no dogs barking to warn of my approach. From that I concluded that this was one of the abandoned inns, of which the innkeeper of Anduhhar had told me.

The nearer I came to the venta, the deeper the silence seemed. At last I arrived and saw an alms box, on which was fastened a notice that read as follows:

“Traveler, take pity and pray for the soul of Gonzalez of Murcia, late innkeeper of the Venta Quemada. Above all, go your way and under no pretext tarry here for the night.”

I promptly made up my mind to brave the dangers with which the notice threatened me. It was not that I was convinced there were no such things as ghosts; but as will be seen later on, the emphasis in my whole education had been upon honor and I had always made a point of never showing any sign of fear.

The sun had just set and I hastened to take advantage of what little light remained to investigate the nooks and crannies of that dwelling, less to reassure myself that no demoniacal presences had taken possession of it than to search for food, for the little I had eaten at Los Alcornoques had stayed, but not satisfied, my gnawing hunger. I passed through any number of bedrooms and salons, most of which were lined with mosaics as high up as a man's head, with ceilings made of that beautiful woodwork on which the Moors lavish all their love of magnificence.

I visited the kitchens, the attics and the cellars. The latter were dug out of rock, some of them leading into underground passages that appeared to penetrate deep into the mountain. But nowhere did I find anything to eat. At last, as the day was drawing to a close, I fetched my horse which I had tied up in the courtyard and led him to a stable where I had noticed a little hay. Then I settled myself in a room that boasted a pallet, the only one left in the whole inn. I should have liked a light, but the good thing about my tormenting hunger was that it kept me from falling asleep.

The blacker the night, however, the gloomier my reflections became. For a while I pondered the strange disappearance of my two servants; then I thought of ways to feed myself. I imagined that thieves, springing out suddenly from behind a thicket or an underground trap, had attacked first Moschito and later Lopez, and that I had been spared only because my military bearing did not promise as easy a victory. I was more concerned about my hunger than anything else. I had seen some goats on the mountain; they were doubtlessly guarded by a goatherd who would certainly have a small supply of bread to eat with his milk. Moreover, I could rely on my gun to provide me with food. But to retrace my steps and expose myself to the ridicule of the innkeeper at Anduhhar—that I definitely would not do. On the contrary, I was determined to continue my journey.

Having exhausted all these reflections, I could not help recalling the famous story of the counterfeiters and several others of that ilk with which my childhood had been nourished. I also thought of the notice tacked on the alms box. Though I didn't believe the devil had wrung the innkeeper's neck, I did not know what his tragic end had been.

The hours passed in deep silence. Suddenly I was startled by the unexpected chime of a clock. It struck twelve times and, as everyone knows, ghosts have power only from midnight till the cock's first crow. I said I was startled and rightly so, for the clock had not chimed the other hours; in short, there was something weird and mournful about its ringing. A moment later, the door opened and I saw a figure enter. It was all black, but not frightening, for it was a beautiful negress, half naked and carrying a torch in each hand.

The negress came up to me, made a deep curtsey and said in excellent Spanish:

“My lord, two foreign ladies, who are spending the night in this inn, invite you to deign to share their supper with them.”

I followed the negress through corridor after corridor and came at last to a large, well-lighted room in the center of which was a table set for three and which was laden with receptacles of fine porcelain and carafes of rock crystal. At the far end of the room was a magnificent bed. A great many negresses stood around waiting to serve us, but they lined up respectfully as two young women entered, their rose and lily complexions in startling contrast to the ebony-colored skins of their servants. The two young women were holding each other by the hand. They were strangely dressed, or so it seemed to me, though actually that style was worn in several cities on the Barbary coast, as I have since discovered in my travels. Their costumes consisted of a linen chemise and a bodice. The linen chemise came to just below the belt, but lower down it was made of Mequinez gauze, a material that would have been completely transparent had not wide silk ribbons, woven into the fabric, veiled charms that gain by being merely divined. The bodice, richly embroidered in pearls and adorned with diamond clasps, covered the breast; it had no sleeves, since those of the chemise, also of gauze, were rolled back and fastened behind the collar. The young women's arms were bare and adorned with bracelets from wrist to elbow. Their bare feet, which, had these two beauties been devils, would have been forked or provided with talons, were encased in tiny embroidered mules, and around their ankles they wore a circlet of large diamonds.

The two strangers came up to me smiling affably. They were strikingly beautiful, the one tall, svelte, dazzling; the other, shy and appealing. The majestic one had a marvelous figure and equally beautiful features. The younger girl's figure was rounded, her lips full, slightly pouting, her eyes half closed so that the little one could see of her pupils was veiled behind extraordinarily long lashes. The eldest addressed me in Castilian:

“My lord,” she said, “we thank you for graciously accepting our little collation. I think you must be much in need of it.”

Those last words sounded so malicious that I almost suspected her of having had our pack-mule carried off, but so lavishly did she replace our missing provisions that I could not be angry with her.

We seated ourselves at the table and the same lady, pushing a porcelain bowl towards me, said:

“My lord, you will find here an olla-podrida, composed of all kinds of meats save one, for we are faithful—I mean, Moslems.”

“Beautiful stranger,” I replied, “that is indeed the right word. Undoubtedly you are faithful, for it is the religion of love. But pray satisfy my curiosity before you satisfy my appetite. Tell me who you are.”

“Pray continue to eat, my lord,” replied the beautiful Moor, “we shall not maintain our incognito with you. My name is Emina and my sister is Zibedde. We live in Tunis; our family comes from Granada and some of our relatives have remained in Spain where they observe in secret the laws of our ancestors. We left Tunis eight days ago, disembarked on a deserted beach near Malaga, then went through the mountains between Sohha and Antequerra and came to this lonely spot to change our clothes and make all necessary arrangements for our safety. You see, my lord, that our journey is therefore an important secret and we are trusting in your loyalty not to betray us.”

I assured the beauties they need fear no indiscretion on my part. Then I began to eat, somewhat greedily to tell the truth, though with certain restrained refinements which a young man willingly assumes when he finds himself the only male in a group of women.

When they saw that my first hunger was appeased and that I was attacking what in Spain is called las dolces (the sweets), the beautiful Emina commanded the negresses to show me some of their native dances. To all appearances no command could have pleased them more. They obeyed with a liveliness that bordered on license. I even think it would have been difficult to stop them had I not asked their beautiful mistresses whether they, too, did not sometimes dance.

In reply, they stood up and called for the castanets. Their steps were reminiscent of the bolero of Murcia and the foffa which is danced in the Algarves; anyone who has visited those provinces can form an idea of it. But he will never know the charm of those two African beauties whose grace was enhanced by their diaphanous draperies.

I watched for a while with a certain composure, but at length their movements, quickened in response to a livelier rhythm, combined with the deafening noise of Moorish instruments and my own spirits raised by sudden nourishment —everything within me and without, united to trouble my reason. I no longer knew whether they were women or insidious succubae. I dared not look; I did not want to watch them. I put my hand over my eyes and I felt myself losing consciousness.

The two sisters came over to me and each took one of my hands. Emina asked me if I felt ill. I reassured her. Zibedde wanted to know what the locket was that I wore around my neck and whether it contained the portrait of my mistress.

“That,” I told her, “is a jewel my mother gave me, which I have promised to wear always. It contains a piece of the true Cross.”

At those words Zibedde recoiled and turned pale. “You are perturbed,” I said, “and yet the Cross can frighten only the Spirits of Darkness.” Emina replied for her sister:

“My lord, you know we are Moslems, and you must not be surprised at my sister's distress. I share it. We regret to see that you, our closest relative, are a Christian. That surprises you, but was not your mother a Gomelez? We are of the same family, which is a branch of the Abencerages. But let us sit down on this sofa and I will tell you more.”

The negresses withdrew. Emina placed me in a corner of the sofa and sat down beside me, legs crossed under her. Zibedde sat on my other side, leaned against my cushion and so close were we that their breath mingled with mine. For a second Emina seemed to be lost in thought, then looking at me keenly, she took my hand.

“Dear Alfonso,” she said, “it is useless to hide from you that we are not here by chance. We were waiting for you. If, out of fear, you had taken another route, you would have lost our esteem forever.”

“You flatter me, Emina,” I replied, “but I do not see what interest you could have in my courage.”

“We take a great deal of interest in you,” replied the beautiful Moor, “but perhaps you will not be so flattered when I tell you that you are almost the first man we have ever seen. That surprises you and you seem to doubt my word. I promised to tell you the story of our ancestors, but perhaps it would be better if I began with our own.”

THE STORY OF EMINA AND HER SISTER ZIBEDDE

We are the daughters of Gasir Gomelez, maternal uncle of the present reigning dey of Tunis. We have never had any brothers, we have never known our father, with the result that, shut up within the walls of the seraglio, we have no idea what your sex is like. As both my sister and I were born with an unusual capacity for tenderness, we loved each other passionately. This attachment dates from our earliest childhood. We wept when they tried to separate us, even for seconds. If one of us was scolded, the other burst into tears. We spent our days playing at the same table, and we slept in the same bed.

This extraordinarily violent emotion seemed to grow with us, being given fresh impetus through a circumstance I am about to relate. I was then sixteen years old, and my sister fourteen. For some time we had noticed that our mother took care to hide certain books from us. At first, we paid little attention, being already extremely bored with the books from which we had learned to read, but as we grew older our curiosity increased. We took advantage of a moment when the forbidden bookcase had been left open and we hastily removed a little volume which proved to be The Loves of Medgenoun and Leille, translated from the Persian by Ben-Omri. That divine work, which painted in colors of fire all the delights of love, turned our young heads. We did not understand it very well because we had never seen human beings of your sex, but we rehearsed their expressions. We were speaking the language of lovers; in short, we tried to make love to each other as they did. I played the part of Medgenoun, my sister that of Leille. To begin with, I declared my passion by the arrangement of flowers, a mysterious sign language much in vogue throughout all of Asia. Then I let my glances speak, I prostrated myself before her, I kissed her footprints, I implored the winds to carry my fond laments to her and with the fire of my sighs I tried to inflame her love.

Faithful to the lessons of her author, Zibedde granted me a rendezvous. I fell at her knees, I kissed her hands, I bathed her feet with my tears. At first my mistress resisted gently, then she permitted me to steal a few favors; at last she yielded to my impatient ardor. In truth, our very souls seemed to mingle, and I still do not know who could make us happier than we were at that time.

I have forgotten how long we indulged in those scenes of passion, but at length our emotions cooled. We became interested in science, particularly in the knowledge of plants, which we studied in the writings of the celebrated Averroes.

My mother, who believed that one could not arm oneself too much against the boredom of the seraglio, was delighted. She sent to Mecca for a holy woman known as Hazareta, or the saint par excellence. Hazareta taught us the law of the prophet. Her lessons were couched in that pure and harmonious language which is spoken in the tribe of Koreisch. We never wearied of listening to her, and we knew by heart almost all the Koran. After that my mother instructed us herself in the history of our house and put in our hands a vast number of memoirs, some in Arabic, others in Spanish. Ah, dear Alfonso, how hateful your law seems to us, how we detested your persecuting priests! But what interest we took, on the other hand, in the many illustrious victims whose blood flows in our veins.

At one time we were all enthusiasm for Said Gomelez who suffered martyrdom in the prisons of the Inquisition; at another, for his nephew Laiss, who lived so long like a savage in the mountains, a life scarcely better than that of wild beasts. From characters like these we learned to love men. We were eager to see some in real life and we frequently went up on our terrace to catch a distant glimpse of people going aboard the schooner on the lake, or on their way to the baths of Haman-Nef. Though we had not forgotten the lessons of the amorous Medgenoun, at least we did not practice them anymore. It even seemed to me there was no longer any passion in my devotion to my sister, but a new incident proved how mistaken I was.

One day, my mother brought a Princess from Tafilet, a middle-aged woman, to see us. We welcomed her cordially. After she had gone, my mother told us she had come to ask my hand in marriage for her son, and that my sister would marry a Gomelez. This was a terrible blow to us. At first, we were so stunned we could not speak. So grieved were we at the thought of living apart, that we gave way to the most terrible despair. We tore our hair; we filled the seraglio with our cries and moans. At length, so extravagant were the demonstrations of our grief that my mother was alarmed. She promised not to force us against our will, assuring us we would be permitted either to remain virgins or to marry the same man. Those assurances calmed us somewhat.

Some time afterwards, my mother came to tell us she had spoken to the head of our family and that he would permit us to share the same husband, provided that husband were of the blood of the Gomelez.

At first we made no answer, but as time went on, we were more and more pleased at the idea of sharing a husband. We had never seen a man, either young or old, save from a distance, but as young women seemed to us more attractive than old women, we hoped our husband would be young. We also hoped he would clear up several passages in Ben-Omri's book which we had not fully understood.

Here Zibedde interrupted her sister and, clasping me in her arms, cried:

“Dear Alfonso, why are you not a Moslem? How happy I should be to see you in Emina's arms, to add to your delights, to be included in your embraces. For, after all, dear Alfonso, in our house as in the house of the prophet, the sons of a daughter have the same rights as the male branch of the family. Perhaps, if you chose, you would become the head of our house, which is on the point of dying out. All you need do, for that, is to open your eyes to the holy truths of the law.”

This smacked so strongly of Satan's tempting that I almost imagined I could see horns on Zibedde's pretty forehead. I stammered a few religious phrases. The two sisters recoiled slightly. Emina looked serious as she continued in the following terms:

“My lord Alfonso, I have spoken too much of my sister and myself. That was not my intention. I sat down here merely to instruct you in the history of the Gomelez, from whom you are descended on the female line. This, then, is what I was about to tell you.”

THE STORY OF THE CASTLE OF CASSAR GOMELEZ

The author of our race was Massoud Ben Taher, son of Youssouf Ben who came to Spain at the head of the Arabs and gave his name to the mountain of Gebal-Taher, which you call Gibraltar. Massoud, who had contributed largely to the success of their arms, obtained from the Caliph of Baghdad the right to govern Granada, where he remained until the death of his brother. He would have stayed there longer, for he was adored as much by Moslems as by Moz-arabs—in other words, Christians still living under Arab dominion. But Massoud had enemies in Baghdad who turned the caliph against him. Realizing that they were resolved to ruin him, he made up his mind to leave. Massoud therefore called his people together and went into hiding in the Alpuharras, which are, as you know, a continuation of the Sierra Morena mountains, and the chain that separates the Kingdom of Granada from the Kingdom of Valencia.

The Visigoths, from whom we wrested Spain, had never penetrated the Alpuharras. Most of the valleys were deserted. Three only were inhabited by the descendants of an ancient Spanish race called the Turdules, a people who recognize neither Mohammed nor your Nazarene prophet. Their religious beliefs and their laws were expressed in songs that had been handed down from father to son. They had once had books, but the books had been lost.

Massoud conquered the Turdules more by persuasion than by force. He learned their language and taught them the Moslem law. The two peoples intermarried, and to this intermingling of races, plus the healthy mountain air, my sister and I owe our high coloring, which is characteristic of the daughters of the Gomelez family. Among the Moors one sees many white women, but they are always pale.

Massoud assumed the title of sheik and built a castle, a veritable stronghold, which he called Cassar-Gomelez. More a judge than a ruler of his tribe, Massoud could be approached at all times and he made a point of being so. But on the last Friday of each moon, he took leave of his family, shut himself up in the lower regions of the castle and there he stayed till the following Friday. These disappearances gave rise to various conjectures: some said our sheik talked with the twelfth Iman who was supposed to appear on earth at the end of time. Others believed that the anti-Christ was held in chains in our vaults. Still others thought the Seven Sleepers (of Ephesus), with their dog, Caleb, lay there. Massoud was undisturbed by those reports; he continued to rule over his people as long as his strength permitted. At length he chose the most discreet man of the tribe, appointed him his successor, handed him the keys of the caverns and retired to his hermitage, where he continued to live for many years.

The new sheik ruled as his predecessor had; like Massoud, he too disappeared on the last Friday of every moon. This went on till the time when Cordova had its own caliphs, independent of Baghdad. At that time, the mountaineers of Alpuharras, who had taken part in that revolution, began to settle in the plains, where they were known as the Abencerages, whereas those who remained loyal to the sheik of Cassar-Gomelez were still known as Gomelez.

The Abencerages, however, bought up the finest lands in Granada and the most beautiful houses in the city. Their display of wealth attracted public attention. The sheik's vaults were said to contain vast treasures, but no one could learn whether this was so, for the Abencerages themselves did not know the source of their riches.

At length, those two beautiful kingdoms brought down upon themselves the vengeance of heaven and fell into the hands of infidels. Granada was captured, and eight days later the celebrated Gonzalvo of Cordova marched into the Alpuharras at the head of three thousand men. Hatem Gomelez was then our sheik. He marched out to meet Gonzalvo and offered him the keys of his castle; the Spaniards demanded the keys of the vaults and the sheik handed them over without a protest. Gonzalvo insisted upon going down into the vaults himself. There, finding only a tomb and a number of books, he made scornful mock of the tales he had been told and hastened to return to Valladolid where love and the delights of love-making called him.

After that, peace reigned in our mountains until the Emperor Charles came to the throne. At that time our sheik was Sefi Gomelez. For reasons no one has ever been able to fathom, Gomelez sent word to the emperor that if he would send a gentleman he could trust into the Alpuharras mountains he, Gomelez, would reveal to him an important secret. Less than two weeks later, Don Ruis of Toledo presented himself, in His Majesty's name, to Gomelez, only to learn that the sheik had been murdered the night before. Don Ruis had a number of persons tortured, but soon wearying of this, he returned to Court.

Meanwhile the sheik's secret was left in the hands of Sefi's murderer. That man, Billah Gomelez by name, gathered together the old men of the tribe and convinced them that they must take fresh precautions to guard such an important secret. They decided to reveal it to several members of the Gomelez family, but with the reservation that each man should be told only a part of it and then only after he had given striking proof of courage, discretion and loyalty.

Here Zibedde again interrupted her sister.

“Dear Emina, do you not think Alfonso would have withstood all the tests? Ah! who can doubt it! Dear Alfonso, if only you were a Moslem! Vast treasures would perhaps be yours for the taking.”

This again was exactly like the Spirits of Darkness who, failing to tempt me with sensual delights, were now trying to make me succumb to the lure of gold. But with the two beauties pressing close against me, there was no doubt in my mind that I was touching bodies and not spirits. After a moment of silence, Emina picked up the thread of her story.

“Dear Alfonso,” said she, “you know enough about the persecutions we suffered under the reign of Philip, the son of Charles. Children were carried off and brought up in the Christian religion. To them were given all the possessions of their parents who had remained faithful to the prophet. That was the time when a Gomelez was received in the Teket of the Dervishes of St. Dominic and fell into the hands of the Great Inquisitor.”

At this point the cock crew and Emina stopped talking. The cock crew a second time. A superstitious man might have expected to see the two beauties fly up the chimney. They did nothing of the kind, but they did seem to be somewhat dreamy and preoccupied.

Emina was the first to break the silence.

“Dear Alfonso,” said she, “day is about to dawn. The hours we have spent together are too precious to waste telling stories. We can be your wives only if you will embrace our holy law, but you are permitted to see us in your dreams. Do you consent?”

I consented to everything.

“That is not enough,” Emina replied with the greatest dignity. “That is not enough, dear Alfonso. Moreover, you must swear by the sacred code of honor never to betray our names, our existence, or anything you know about us. Have you the courage to take this solemn pledge?”

I promised everything they asked.

“That will do,” said Emina. “Sister, bring the cup consecrated by Massoud, our first chieftain.”

While Zibedde went to fetch the magic cup, Emina prostrated herself and recited some prayers in Arabic. Zibedde returned bearing a goblet that looked to me as if it were cut out of a single emerald. She moistened her lips in it; Emina did likewise and then ordered me to drain the cup at one gulp.

I obeyed her.

Emina thanked me and embraced me tenderly. Zibedde then pressed her lips on mine as if she would never take them away. At last they left me, saying that I would see them again and they would advise me to fall asleep as soon as possible.

So many strange events, such astonishing tales and such unexpected emotions would undoubtedly have given me enough to think about all night long, but I must confess I was more interested in the dreams they had promised me, and I made haste to undress and get into a bed they had prepared for me. I was pleased to note that my bed was unusually wide; and dreams, I said to myself, do not need so much room. But no sooner had I made that reflection than I was overcome by an irresistible drowsiness; my eyelids closed and all the delusions of the night laid hold of my senses. I felt them being led astray by incredible marvels. My thoughts, borne, in spite of myself, on the wings of desire, set me down in the midst of African seraglios and took possession of the charms confined within those walls to make them my chimerical delights. I knew I was dreaming and yet I was conscious that the form I held in my arms was not a dream. I was lost on the crest of the maddest illusions, but I was always with my beautiful cousins. I fell asleep on their breasts. I awoke in their arms. I do not know how many times I enjoyed those sweet alternatives.

The second day

When at last I awoke, the sun was burning my eyelids; I could scarcely open them. I saw the sky. I saw that I was out of doors. But my eyes were still heavy with sleep. I wasn't really asleep, neither was I fully awake. Visions of tortures flashed through my mind, one after the other. I was horrified and I sat up with a start.

What words can express my horror when I realized that I was lying under the gallows of Los Hermanos, and beside me—the corpses of Zoto's two brothers! I had apparently spent the night with them. Then I noticed that I was lying on a conglomeration of rope, broken wheels, remains of human carcasses and the ghastly rags that had rotted and dropped from their bodies.

I thought I was still not fully awake and was having a nightmare. I shut my eyes and tried to remember where I had been the night before... Then I felt talons dig deep into my side. A vulture was sitting on top of me while he devoured one of my companions. The pain of his talons at last brought me wide awake. I saw that my clothes lay near me and I made haste to put them on. My first thought, as soon as I was dressed, was to get out of this enclosure around the gallows, but the gate was nailed fast and try as I might I could not force it. I was therefore obliged to climb those gloomy walls. Then, leaning against one of the gallows posts, I surveyed the surrounding countryside. It was not difficult to get my bearings: I was at the entrance to the valley of Los Hermanos, not far from the banks of the Guadalquiver.

Down near the river I saw two travelers, one of whom was preparing a meal while the other held their horses' bridles. I was so pleased to see human beings that my first reaction was to call out “Agour, Agour!” which in Spanish means “Good morning” or “I salute you!”

The two travelers, who could see that someone was calling to them from the top of a gallows, appeared to hesitate a second, then suddenly they mounted their horses, put them to a fast gallop and were off like the wind along the Alcornoques road. I shouted to them to stop, but it was no use; the more I shouted the faster they spurred on their mounts. When they were out of sight, I jumped down from my post and in so doing injured my leg.

Limping slightly, I managed to reach the banks of the Guadalquiver and there I found the repast which the two travelers had left behind. Nothing could have been more welcome, for by this time I was exhausted. There was some chocolate, which was still hot, sponhao dipped in Alicante wine, and bread and eggs. I set to work to replenish my strength, after which I reflected on my experiences of the past night. My memories were extremely confused, but I clearly recalled having given my word of honor to keep my cousins' secret and I was firmly resolved to do so. That point once settled, all that was left was to plan my next move— in other words, decide which road I should take. And it seemed to me that more than ever I was in honor bound to go by way of the Sierra Morena.

You will perhaps be surprised to find me so concerned about my honor and so little with the events of the previous night. But that was again the result of the education I had received—as will be seen by what follows. For the moment I shall go on with the story of my journey.

I was curious to know what the demons had done with my horse, which I had left at the Venta Quemada. As my road lay in that di [...]