0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

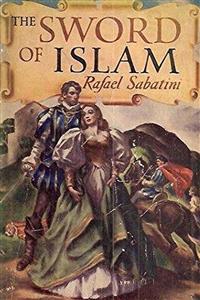

A story of high adventure, of shifting loyalties, of a long road to revenge, of conflict between city states, and of the love of a lovely lady who rescues the captain's nephew when he flees the fleet, and nurses him through the Plague.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

The Sword of Islam

by Raphael Sabatini

First published in 1939

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

The Sword of Islam

▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂

by

CONTENTS

I.

The Author of ‘The Liguriad’

II.

The Doge

III.

Surrender

IV.

The Castelletto

V.

The Battle of Amalfi

VI.

The Prisoner

VII.

At Lerici

VIII.

The City of Death

IX.

The Garden of Life

X.

Waters of Lethe

XI.

Procida

XII.

The Amend

XIII.

Mother and Son

XIV.

Scipione de’ Fieschi

XV.

The Adorno Honour

XVI.

The Choice

XVII.

Cherchell

XVIII.

Dragut’s Prisoner

XIX.

Monna Aurelia’s Indiscretion

XX.

The Homecoming

XXI.

Explanation

XXII.

The Way Out

XXIII.

Capture

XXIV.

A Prize for Suleyman

XXV.

The Trap

XXVI.

The Plan

XXVII.

The Reunion

XXVIII.

At a Venture

XXIX.

The Return

XXX.

Reparation

XXXI.

Mars Ultor

XXXII.

The Battle of Cape Mola

XXXIII.

The Rehabilitation of an Emperor

XXXIV.

The Discovery

XXXV.

The Last Hope

XXXVI.

The Investiture

I THE AUTHOR OF THE LIGURIAD

WITH banners limp in the breathless noontide August heat, the long line of blockading galleys rode drowsily at anchor, just out of gunshot from the shore, at a point where the water, smooth as an enamelled sheet, changed from emerald to sapphire.

From this station Andrea Doria commanded the gulf, from the rugged promontory of Portofino in the east to the distant Cape Melle in the west, and barred the sea approaches to Genoa the Superb, which rose, terrace upon terrace, in glittering marble splendour within the embrace of her encircling hills.

In the rear of his long line were stationed, as became an ancillary squadron, the seven red Pontifical galleys. Richly carved and gilded at stem and stern, they displayed at their mastheads the Papal vexilla: on one the keys of Saint Peter, on the other the besants of the Medici, the House from which His Holiness was sprung. From each red flank the thirty massive oars, thirty-six feet in length, were inclined astern and slightly upwards, presenting, thus at rest, the appearance of a gigantic, half-closed fan.

In the tabernacle—as the poop cabin was termed—of the rearmost galley, a sybaritic chamber, hung and carpeted with the glowing silks of Eastern looms, sat the Papal Captain, that Prospero Adorno who was at once a man of dreams and a man of action, a soldier, and a poet. Other poets have acknowledged him a great soldier, and other soldiers have acknowledged him a great poet. Both state the truth, and only jealousy makes them state it in this wise.

As a poet he lives on and sings to you from The Liguriad, that immortal epic of the sea, whose subject is proclaimed by its opening lines:

Io canto i prodi del liguro lido,

Le armi loro e la lor’ virtù.

As a soldier let it be said at once that he achieved a celebrity never approached by the military deeds of any other poet. Just thirty years of age at the time of this blockade of Genoa, he was already famous as a naval condottiero. Four years ago in an action off Goialatta his skill and intrepidity had saved the great Andrea Doria from disaster at the hands of Dragut-Reis, the Anatolian who for his deeds had come to be known as The Drawn Sword of Islam.

Acclaimed as having plucked a Christian victory from an imminent defeat, his fame had swept like a mistral across the Mediterranean, and it resulted naturally that when, later, Doria passed into the service of the King of France, it was Prospero Adorno who succeeded him as Captain-General of the Pontifical Navy.

Now that His Holiness had entered into alliance with France and Venice against the Emperor, whose troops had scandalized the world by the sack of Rome in May of that year 1527, Andrea Doria, as the Admiral of the King of France and the foremost seaman of his day, was in supreme command of the allied navies; and thus Prospero Adorno found himself once more serving under Doria’s orders. Apparently it placed him in the invidious position of bearing arms against a republic of which his own father was the Doge. Actually, however, since the campaign had for object to break the Imperial yoke under which Genoa groaned, the blockade to which he brought his galleys sought to restore his native land to independence and change his father’s status from that of a puppet-doge at the orders of an Imperial governor to that of an authoritative prince.

From where he now sat, just within the arched entrance of the tabernacle, his calm eyes, so dreamy and slow-moving that they appeared never to see anything, commanded the entire length of the vessel to its rambade, the raised bastion or forecastle in the prow, a hundred and twenty feet ahead of him. Along the narrow gang-deck between the rowers’ benches two slave-wardens slowly paced, and under the arm of each was tucked his whip with the long lash of bullock-hide. On either side of this deck, and below the level of it, the idle slaves drowsed in their chains. There were five men to each oar, three hundred in all; unfortunates of many a race and creed: dusky, sullen Moors and Arabs, tough, enduring Turks, melancholy negroes from the Sus, and even some alien Christians, all rendered kin by misery. From where he sat the Captain could see only their shorn heads and naked, weathered shoulders. Groups of soldiers paced or lounged in the deadworks of the galley, the galleries projecting over the water from the vessel’s sides throughout her length; others squatted on the broad platform amidships, between the kitchen on one side and the heavy ordnance on the other, taking advantage of the shade cast by the sloop that was at rest there upon its blocks.

A sudden blare of trumpets snapped the thread of the Captain’s dreaming. An officer, ascending the companion, rose into view, and stood before the entrance of the cabin.

‘The Captain-General’s barge is coming alongside, Sir Captain.’

Prospero came instantly to his feet with an effortless resilience. It was in this athletic ease of movement, in the long limbs and the broad shoulders, from which he tapered down over lean flanks, that you perceived the man of action. The width of his brow made his shaven countenance look narrow. In the wide, wistful eyes of the visionary and the long, mobile mouth you would have sought in vain the soldier. It was a face that had inherited none of the beauty so arresting in the portrait of his high-spirited, foolish Florentine mother, that Aurelia Strozzi whom Titian painted. Only the bronze-coloured hair, and the vivid blue, though not the elongated shape, of her handsome eyes were repeated in her son. From the sombre richness of his dress, without ornament beyond the girdle of hammered gold slung diagonally over his hips to carry the heavy dagger, you might suppose that in matters of taste he had gone to school to that mirror of courtliness, Baldassare Castiglione.

He was waiting on the vestibule of the poop when the twelve-oared barge drew alongside, trailing a white standard, flecked with golden fleurs-de-lys. From her stern-sheets three men rose and came up the short ladder to the deck. Two of them were big men, but of these the foremost, standing well over two yards high, was almost a half-head taller than the next. The third, more lightly built, was not above middle height.

They were Andrea Doria and his nephews Gianettino and Filippino. Comeliness was no characteristic of the males of the House of Doria, but in the aspect of the stalwart sexagenarian, with his fierce, reddish eyebrows, his great promontory of a nose, and his long, fan-shaped, fulvid beard, there was something venerable, heightened by the stern, controlled dignity with which he hedged himself about. There was strength in the long jaw, intelligence in the lofty brow, from which the thin hair was receding, and craft in the narrow, deep-set eyes. He carried his sixty years with the active, erect virility of a man of forty.

Gianettino, who immediately followed him aboard, was massive and ungainly. His face was a woman’s, and without being ugly was repellent on that account. It was round and shaven, with a long, straight nose and a short chin. There was meanness in the beady eyes and petulance in the small mouth. In his endeavour to emulate the cold aloofness of his uncle he achieved no more than an aggressive arrogance. Men spoke and thought of him as Andrea Doria’s nephew. Actually he was the son of a distant cousin in poor circumstances, and he might have pursued his father’s trade as a silk-weaver had not his uncle, that childless nepotist, adopted and reared him, to pamper him with an indulgence that was destined ultimately to bring the upstart to an untimely end. In apparel he displayed the fundamental ostentation of his nature. His parti-coloured hose and parti-coloured sleeves, modishly puffed and slashed, made him a bewilderment to the eye, in black and white and yellow.

In age both nephews were approaching thirty. Both were black-haired, dark-complexioned men. Beyond this they presented no resemblance. Filippino, as restrained in his dress as Gianettino was flamboyant, displayed something of the same contrast in his person. Lithe and nimble, he moved with a quick, soft tread, stooping a little, where his cousin rolled and swaggered aggressively erect. Of the weakness in Gianettino’s countenance there was no sign in Filippino’s. A nose at once aquiline and fleshly overhung his short upper lip; his eyes, of the colour of mud, were prominent and low-lidded; the short black beard was of too feeble a growth to dissemble the narrowness of his jaw. He carried a bandaged right arm in a sling of black taffeta, and his manner was distempered and sullen.

Almost before they were well within the cabin, and without waiting, as deference dictated, for his uncle to speak, it was he who took the lead, his manner viperish.

‘Our faith in your father, Sir Prospero, cost us rather dear last night. Close upon four hundred men lost, some seventy of them killed outright. You’ll not yet have heard that our cousin Ettore has since died of the wounds he took. I have brought back this keepsake from Portofino.’ He pointed to his arm. ‘That I have brought back my life is no thanks to you.’

Without pause his cousin followed up the onslaught that was taking Prospero completely by surprise. ‘The fact is that our faith has been abused. A trap has been sprung on us. A cursed treachery for which we have to thank Doge Adorno.’

Prospero’s clear eyes looked frigidly from one to other of the ranting twain. There was a stateliness in his self-control. ‘Sirs, I understand your words as little as your manner. You’ll not imply that my father is responsible for the defeat of your rashly attempted landing?’

‘Rashly attempted!’ flared Filippino. ‘Lord God!’

‘I judge from what I was told last night. To have been so instantly and heavily repulsed scarcely argues a properly cautious approach. It was not to be supposed that the Spaniards would slumber at so vulnerable a point.’

‘Aye, if they had been Spaniards!’ bellowed Gianettino. ‘But Spaniards were not concerned.’

‘How, not concerned? Last night your tale was that Imperial troops had met your surprise party in overwhelming numbers.’

At last Andrea Doria intervened. His quiet voice, his gravely placid manner contrasted with the violence of his nephews. Displays of heat were rare in him. ‘We know better today, Prospero. We have some prisoners. They are not Spaniards, but Genoese. Of the militia. And we know now that it was led by the Doge himself.’

Prospero stared in blank surprise at each in turn. ‘My father led a Genoese force against you!’ He almost laughed. ‘That is not credible. My father knows our aims.’

‘Does it follow that he is in sympathy with them?’ asked Gianettino. ‘We have supposed——’

Warmly Prospero interrupted him. ‘To doubt it is to insult him.’

The Lord Andrea intervened again, conciliatory. ‘You’ll be patient with their heat,’ he begged. ‘The death of Ettore has deeply affected us. After all, we must remember—perhaps we should have remembered before—that Doge Adorno holds the ducal crown from the Emperor. He may fear that what came with the Emperor may go with the Emperor.’

‘Why should he? Without Genoese support he could not have been elected. With it he cannot be deposed. Sirs, your information must be as false as your assumptions.’

‘Our information leaves no doubt,’ Filippino answered him. ‘As for the assumptions, your father will know that Cesare Fregoso is in command of the French troops investing him by land. He will not have forgotten that a Fregoso was dispossessed by him of the dogeship. That may make him doubt his own position should the French prevail.’

Prospero shook his head. But before he could speak, Gianettino was adding stormily: ‘It’s these accursed factions that poison faith; this ages-old struggle of Adorni, Fregosi, Spinoli, Fieschi, and the rest. Each brawling for dominion in the State. For generations it has been the Republic’s nightmare. It has rotted the sinews of this Genoa that once was mightier than Venice. Bled white by your cursed strife she has fallen under the heel of foreign despots. We are here,’ he bellowed, ‘to make an end of native factions as well as foreign usurpation. We are in arms to restore to Genoa her independence. We are here to——’

Prospero’s patience gave out. ‘Sir, sir! Save the rest for the market-place. No need here for orations in the manner of Titus Livy. Why we are besetting Genoa I know. Otherwise I should not be with you.’

‘That,’ said the elder Doria, quietly authoritative, ‘should be assurance enough for your father even if he forgets that I am Genoese to the marrow of my spine, and that the good of my country must always be my only object.’

‘My letters,’ said Prospero, ‘assured him that we serve the coalition only so that we may the better serve Genoa. I wrote of the undertaking to you from the King of France, that Genoa shall be restored at last to independence. It must be,’ he concluded, ‘that my letters never reached him.’

‘That is a possibility I have considered,’ said the Lord Andrea.

His volcanic nephews would have argued upon it. But quietly he repressed them.

‘After all, it may be the explanation. The Milanese is full of de Leyva’s Spaniards, and your courier may have been captured. It but remains to write to him again, so that bloodshed may be saved and the gates of Genoa opened to us. The Doge should have enough native militia to overpower the Spaniards in the place.’

‘How shall I get the letter to him now, from here?’ asked Prospero.

The Lord Andrea sat down. He set one hand on his massive knee, and with the other thoughtfully stroked his length of beard. ‘You might send it openly, under a flag of truce.’

Prospero moved slowly about the cabin, pondering. ‘It might be intercepted again by the Spaniards,’ he said at last, ‘and this time it might be dangerous for my father.’

A shadow darkened the entrance of the tabernacle. Prospero’s lieutenant stood on the threshold.

‘Your pardon, Sir Captain. A fisherman of the gulf is alongside. He says he has letters for you, but will deliver them only into your own hands.’

There was a pause of surprise. Then Gianettino swung round hotly upon Prospero. ‘Do you correspond then with the city? And you ask——’

‘Patience!’ his uncle suppressed him. ‘What profit is there in assumptions?’

Prospero glanced at Gianettino without affection. ‘Bring in this messenger,’ he shortly ordered.

And no more was said until a bare-legged youngster had pattered up the companion to the officer’s beckoning, and was thrust into the tabernacle. The lad’s dark eyes shifted keenly from one to another of the four men before him. ‘Messer Prospero Adorno?’ he inquired.

Prospero stood forward. ‘I am he.’

The fisherman drew a sealed package from the breast of his shirt, and proffered it.

Prospero glanced at the superscription, and his fingers were scarcely steady when he broke the seal. Having read the contents with a darkening countenance, he looked up to find the eyes of the three Dorias watching him. He handed the letter in silence to the Lord Andrea. Then to his officer, indicating the fisherman, ‘Let him wait below,’ he said.

From the Lord Andrea came presently a sigh that was of relief. ‘At least this shows that your surmise was right, Prospero.’ He turned to his nephews. ‘And yours,’ he told them, ‘without justification.’

‘Let them read for themselves,’ said Prospero.

The Admiral handed the sheet to Gianettino.

‘It’s a warning to you both against rash assumptions,’ he gently chided his nephews. ‘I am glad to know that His Serenity’s action comes from a lack of understanding of our aims. Once you will have informed him, Prospero, by the means now supplied you, we may confidently hope that Genoa’s resistance will be at end.’

There was a silence whilst the nephews together read the letter.

‘From prisoners taken last night at Portofino,’ wrote Antoniotto Adorno, ‘I learn with consternation that you are in command of the Papal squadron of the fleet blockading us. But for assurances which make doubt impossible, I could not credit that you are in arms against your native land, much less that you should be in arms against your own father. Although no explanation seems possible, yet unless something has happened to change your whole nature, some explanation there must be. A fisherman of the gulf will take this to you, and will no doubt be allowed to reach you. He will bring me your answer if you have one, which I pray God you may have.’

Filippino looked darkly at his uncle. ‘I share your hope, sir, but not your confidence. To me the Doge’s tone is hostile.’

‘And to me,’ Gianettino agreed with him. He swung arrogantly to Prospero. ‘Make it plain to His Serenity that he can do himself no greater harm than by resisting us. In the end the might of France must prevail, and the Doge will be held responsible for any blood unnecessarily shed.’

Prospero looked squarely and calmly into that countenance, so weak of feature and yet so bold of expression. ‘If you have such messages for my father, you may send them in your own hand. But I should not advise it. For I never yet knew an Adorno who would yield to bullying. You might remember that also, Gianettino, when you speak to me. If anyone has told you that there are no limits to my patience, he has lied to you.’

It might have been the prelude to a very pretty quarrel if the Admiral had not been quick to smother any further provocation from his bristling nephews. ‘Faith, you’ve been too patient already, Prospero, as I shall make these malaperts understand.’ He rose. ‘No need to incommode you any longer, now that all is clear. We but delay the dispatch of your letter.’

And he drove out the arrogant pair before they could work further mischief.

II THE DOGE

THE patriotism of His Serenity the Doge Antoniotto Adorno stood high enough to surmount the tribulation of those days.

Behind her proud exterior, under her marble splendours, effulgent in the burning August sunshine, Genoa was succumbing to starvation. Of the troops sent by Marshal de Lautrec to invest her by land, she might be contemptuous. Abundantly were her flanks and rear protected by the towering natural ramparts, the bare, craggy masses forming the amphitheatre in which she was set. If she was vulnerable along the narrow littoral at the base of these mountain bastions, yet here any attack, from east or west, would be as easy to repel as it would be hazardous to launch.

But the forces which knew themselves utterly inadequate to attempt an assault were more than adequate to cut off her supplies; and for ten days before the arrival of Doria in the gulf, the sea approaches had effectively been guarded by seven Provençal war-galleys from Marseilles, which were now incorporated in the Admiral’s fleet. So Genoa had begun to know starvation, and starvation never fostered heroism. A hungry population is prone to rebel against whatever government sits over it, visiting the blame for the famine upon its rulers. And lest the population of Genoa should be slow to rebel now, the Fregosi faction, in its rivalry of the Adorni for dominion in the Republic, perceived its opportunity and employed it ruthlessly. Those who form the populace are ever the ready gulls of the promises of crafty opportunists; and the populace of Genoa gave heed now to hollow promises of a golden age, to be ushered in by the King of France, which would not merely set a term to the present pangs of hunger, but create for all time an abiding and effortless abundance. So from artisans, from sailmakers, from fishermen who no longer dared put to sea, from stevedores’ labourers, from carders, from sailors, from caulkers and all those who toiled in the shipbuilding yards, and from all those who made up the less defined sections of the people came the angrily swelling demand for surrender.

Up and down the streets of Genoa, so steep and narrow that a horse was rarely seen in them and the mule was the common beast of burden, moved with increasing menace in those hot days a people in revolt against a Doge who—because the devil he knew seemed preferable to the devil with whom he had yet to become acquainted—accounted it his duty to the Emperor to persist in holding out against the King of France and his Papal and Venetian allies.

With the menace from without he had shown last night at Portofino that he was competent to deal, whilst awaiting the relief that sooner or later should reach him from Don Antonio de Leyva, the Imperial Governor of Milan. But the menace from within was of graver sort. It left him to choose between impossible courses. Either he must employ his Spanish regiment to quell the insurgence, or else he must surrender the city to the French, who would probably deal with it as the German mercenaries had dealt with Rome. From this cruel dilemma Prospero’s answer to his letter almost brought relief.

With that letter in his hand, the Doge now sat in a room of the Castelletto, the red fortress, deemed impregnable, that from the eastern heights dominated the city. The chamber was a small one in the eastern turret, hung with faded blue-grey tapestries, an eyrie commanding from its narrow windows a view of the city, the harbour, and the gulf beyond, where the blockading fleet rode on guard.

The Doge reclined in a high, broad chair of blue velvet, his right elbow on the heavy table. His left arm was in a sling, so as to ease the shoulder, in which he had taken a pike-thrust last night at Portofino. Perhaps because the heavy loss of blood left him chilled even in that sweltering heat, he was wrapped in a cloak. A flat cap was pulled down over his high, bald forehead, deepening the shadows in his pallid, hollow cheeks.

Beyond the table stood the Dogaressa; a woman moderately tall, and still, even now, in middle life, of a slender, graceful shape, retaining in her finely chiselled features much of the beauty that in her youth had been sung by poets and painted by the great Vecelli, she possessed the masterfulness that comes to all egoists who have been greatly courted.

With her were the middle-aged patrician captain, Agostino Spinola, and Scipione de’ Fieschi, the handsome, elegant younger brother of the Count of Lavagna, who was a Prince of the Empire and of a lineage second to no man’s in the State of Genoa.

Having read his son’s letter once, the Lord Antoniotto sat long in a silence which not even his imperious lady ventured to disturb. Then he read it yet again before attempting to speak.

‘You cannot suppose,’ ran the vital part of it, ‘that I should be where I am if the cause we serve were not the cause of Genoa rather than that of the Alliance. We come, not to support the French, but supported by the French; not so much to promote French interests as to deliver Genoa from foreign thraldom and establish her independence. Therefore I have not hesitated to continue in command of a squadron that is bearing part in so laudable a task, confident that once you were made aware of the real aim you would join eager hands with us in this redemption of our native land.’

The Doge raised at last his troubled eyes, and looked from one to the other of his companions.

The Dogaressa’s patience gave out. ‘Well?’ she demanded. ‘What has he to say?’

He pushed the sheet across the table to her. ‘Read it for yourself. Read it to them.’

She snatched it up and read it aloud, and when she had read she pronounced upon it. ‘God be praised! That should settle your doubts, Antoniotto.’

‘But is it to be believed?’ he questioned gloomily.

‘What else,’ Scipione asked him, ‘could explain Prospero’s part?’

Less quietly the Dogaressa added the question: ‘Are you doubting your own son?’

‘Not his faith. No. Never that. But the trust in others on which it stands.’

Scipione, whose ambitious, intriguing soul was fierce with hatred of all the Doria brood, was quick to agree. But the Dogaressa paid no heed.

‘Prospero is never rash. He is like me; more Florentine than Genoese. If he writes positively, it is because he is positive.’

‘That the French have no thought of profit? That is to be credulous.’

‘What do you gain by mistrust?’ she demanded. ‘Can’t even Prospero persuade you that if you hold your gates against Doria now, you hold them against the best interests of your country?’

‘Dare I be persuaded? Heaven help me! I am in a fog. The only thing that I see clearly is that I hold the ducal crown from the Emperor. Have I, then, no duty to him?’

He seemed to put the question to them all. It was answered by Madonna Aurelia.

‘Is not your highest duty to Genoa? Whilst you stand balancing between the cause of the Emperor and the cause of your own people, the only interest you are really serving is that of the Fregosi. Have no illusions upon that. Give heed to me. You should know by now that I am clear-sighted.’

The Doge’s heavy glance sought Spinola’s, plainly asking a question.

The stalwart captain raised shoulders and eyebrows expressively.

‘To me it seems, Highness, that what Prospero tells us changes everything. As between the Emperor and the King of France, your duty, as you say, is clearly to the Emperor. But as between either of them and Genoa, your duty, as Prospero assumes, is still more clearly to Genoa. That is how I see the thing. But if Your Serenity sees otherwise and is determined to resist, why then you must resolve to crush the mutineers.’

Gloomily the Doge considered. Gloomily, at last, he sighed. ‘Yes. It is well argued, Agostino. Yes. And it is thus Prospero will have argued.’

Scipione interposed. ‘His presence and his assurances would make the case for surrender very strong.’ But he added, with a tightening of the lips: ‘Provided that you could trust Andrea Doria.’

‘If I mistrust him, of what shall I mistrust him?’

‘Of too much ambition. Of aspiring to become Prince of Genoa.’

‘With that danger we can deal when it arises. If it arises.’ He shook his head, and sighed. ‘I must not sacrifice the people and set Genoese blood flowing in the streets because of no more than that mistrust. So much, at least, seems clear.’

‘In that case,’ said Spinola, ‘nothing hinders Your Serenity’s decision.’

‘Saving, of course,’ Scipione added, and it is easy to conceive the sneer in his tone, ‘that for Prospero’s faith there is no warrant but the word of Andrea Doria.’

III SURRENDER

THE account which Scipione de’ Fieschi has left us of that scene in the grey chamber of the Castelletto ends abruptly on that answer of his. Either he was governed by a sense of drama, of which other traces are to be discovered in his writings, or else in what may have followed the discussion did no more than trail to and fro over ground already covered.

He shows us plainly at least the decision towards which the Doge was leaning, and we know that late that evening messengers went to Doria aboard his flagship and to Cesare Fregoso at Veltri offering to surrender the city. The only condition made was that there should be no punitive action against any Genoese and that the Imperial troops should be allowed to march out with their arms.

This condition being agreed, Don Sancho Lopez departed with his regiment early on the morrow. The Spaniard had argued fiercely against surrender, urging that sooner or later Don Antonio de Leyva must come to their relief. But the Doge, fully persuaded by now that what he did was for Genoa’s good, stood firm.

No sooner had the Spaniards marched out than Fregoso brought in three hundred of his French by the Lantern Gate to the acclamations of the populace, who regarded them as liberators. Fregoso’s main body remained in the camp at Veltri, since it was impossible to quarter so many upon a starving city.

Some two or three hours later, towards noon, the galleys were alongside the moles, and Doria was landing five hundred of his Provençal troops, whilst Prospero brought ashore three hundred of his Pontificals.

They were intended for purposes of parade, so as to lend a martial significance to the occasion. But before the last of them had landed, it was seen that they were needed in a very different sense.

It might be Cesare Fregoso’s view that his French troops came to Genoa as deliverers of a people from oppression; but the actual troops seem to have been of a different opinion. To them Genoa was a conquered city, and they were not to be denied the rights over a conquered city in which your sixteenth-century mercenary perceived the real inducement to adopt his trade. Only the fear of harsh repression, which they were not in sufficient force to have met, could have restrained their lusts. But in the very people who might have repressed them, the populace which for days now had been in a state of insurgence against the government, they discovered allies and supporters. No sooner had the French broken their ranks and committed one or two acts of violence than the famished rabble took the hint of how it might help itself. At first it was only in quest of food that these ruffians forced their way into the houses of wealthy merchants and the palaces of nobles. But once committed to this violence they did not confine it to the satisfaction of their hunger. After other forms of robbery came the sheer lust of destruction ever latent in the ape-like minds of those who know not how to build.

By the time the forces were landed from the galleys, Genoa was delivered over to all the horrors of a sack, with the added infamy that in this foulness some hundreds of her own children wrought side by side with the rapacious foreign soldiery.

In fury Prospero thrust his way through a group of officers about Doria on the mole. But his anger was silenced by the aspect of Doria’s countenance, grey and drawn with a horror no less than Prospero’s own.

The Admiral divined his object from the wrath in his eyes. ‘No words now, Prospero. No words. There is work to do. This foulness must be stemmed.’ And then his heavy glance alighted on another who strove to approach him, a short, thick-set man in a back-and-breast of black steel worn over a crimson doublet. Under his plumed steel cap the face, black-bearded and bony and disfigured by a scar that crossed his nose, was livid and his eyes were wild. It was Cesare Fregoso.

Doria’s glance hardened. He spoke in a growl. ‘What order do you keep that such things can happen?’

That challenge went to swell the soldier’s passion. ‘What order do I keep? Is the blame mine?’

‘Whose else? Who else commands this French rabble?’

‘Jesus God! Can a single man contain three hundred?’

‘Three thousand if he’s fitted for command.’ Doria’s sternness was terrible in its calm.

Bubbles formed on Fregoso’s writhing lips. In his anxiety to exonerate himself he was less than truthful. ‘Set the blame where it belongs: on that fool of a Doge, who out of servility to the Emperor, caring nothing for his country’s good, drove the people mad with hunger.’

And suddenly he found support from Filippino, who stood scowling at his uncle’s side. ‘Faith, Ser Cesare sets his finger on the wound. The blame is Antoniotto Adorno’s.’

‘As God’s my life, it is,’ Fregoso raged. ‘These wretched starvelings were not to be restrained once the Spaniards were out of the place. Adorno’s futile resistance had made them desperate. And so they go about helping themselves instead of helping Genoa to protect her property, as they would have done if——’

There Doria interrupted the ranter. ‘Is it a time to talk? Order must be restored. Words can come later.’

Prospero leaned over, and touched Fregoso’s arm. ‘And a word from me will be amongst them, Ser Cesare. Also a word to you, Filippino.’

Doria denied them leisure in which to answer.

‘Stir yourselves, in the name of God. Leave bickering.’ He swung to Prospero. ‘You know what is to do. About it! Take the east side. I’ll see to the west. And use a heavy hand.’

So as to make it all the heavier, Prospero ordered one of his captains, a Neapolitan named Cattaneo, to land another two hundred men. He took the view that since the looters were roving the city in bands it was necessary to break up his troops similarly into bands, so as to deal with them. Accordingly he divided his forces into little companies of a score men, to each of which he appointed a leader.

Of one of these companies he assumed the command, himself; and almost at once, in the open space by the Fontanelle, not a hundred yards from the quays, he found employment for it in the violated dwelling of a merchant. A mixed band of French soldiers and waterside ruffians were actively looting the house, and Prospero caught them in the act of torturing the merchant, so as to make him disclose where he kept his gold.

Prospero hanged the leader, and left his body dangling above the doorway of the house he had outraged. The others, under the merciless blows of pike-butts, were driven forth as harbingers of the wrath that was loose against all pillagers.

From this stern beginning, Prospero swept on to pursue his work with swift and summary ruthlessness. Once when, perhaps, the poet in him inspired poetic justice, he caught the ringleader of a gang guzzling in a nobleman’s wrecked cellar, he had the fellow thrust head foremost into a hogshead of wine, and submerged at least a dozen times almost to the point of drowning, so that for once he might drink his fill. In the main, however, he lost no time in such refinements. He did what was to do at speed, and at speed departed, never staying for the curses of those whose bones he broke or the thanks of those he delivered.

Working eastwards and upwards to the heights of Carignano, he came towards noon into a little space before a tiny church, where acacia trees made a square about a plot of grass. It was a pleasant, peaceful spot, all bathed in sunlight, fragrant with the blossoms that clustered like berries of gold on the feathery branches. He paused there to assemble his men, so that they might keep together, for some five of them, who had been hurt in the course of their repressive activities, were lagging in the rear.

A distant sound of male voices, raucous with mirth, flowed out of an alley on the left of the church and above the level of the square, reached by six steps rising under an arch. Suddenly, as Prospero listened, there was a swift succession of crashes, as of timbers being rent by heavy blows. Laughter rose louder, receded, and then, like a clarion call came the piercing scream of a woman.

Up the steps with every sound man of his company at his heels leapt Prospero. The way was gloomy, lying between high walls, the one on his right being thick with ivy from foot to summit. Twenty paces on a patch of sunshine broke the gloom, where a doorway gaped, the door hanging battered on its hinges. To this he was guided by repeated screams, and the sounds of ugly laughter that were hideously mingled with them.

Under the lintel Prospero paused at gaze. He had a fleeting glimpse of a wide garden space, of greensward, trim hedges, flowering shrubs, a vast fountain splashing into a pool, the white gleam of statuary against the green, and as a background to it all the wide façade of a palace in black and white marble rising above a delicate Romanesque colonnade. Of all this his impression was no more than vague. His attention went first to a youth in a plain livery that betokened the servant, who lay prone upon the grass in a curious twisted way, with arms outflung; near him sat an older man, his elbows on his knees, his head in his hands, and blood streaming between the fingers of them. The continuing outcries drew his glance on to behold a woman, whose upper garments hung torn about her waist, fleeing in terror. After her through the shrubs, with whoops of laughter crashed a pair of ruffians, whilst away on Prospero’s left, against the garden’s high wall stood another woman, tall, slim, and straight, confronting wide-eyed the menacing mockery of yet another of these brigands.

Seeking afterwards to evoke in memory her image, all that he could remember was that she was dressed in white with a glint of jewels from the caul that confined her dark hair, so fleeting had been his glance, so intent his mind upon his purpose there.

He stepped clear of the threshold to give admission to his men.

‘Make an end of that,’ was his sharp, brief order.

Instantly a half-dozen of his troopers plunged after those who were hunting the woman in the garden’s depth, whilst others made for the rascal who was baiting the lady in white.

The man had spun round at the stir behind him, and by instinct rather than by reason dropped a hand to his hilt. But before he could draw they were upon him. His steel cap was knocked off, his sword-belt was removed, and the straps of his back-and-breast were severed by a knife. Thus deprived of arms and armour, pike-butts thrust him towards the doorway, pike-staves fell about his shoulders until he cried out in pain and terror whilst stumbling blindly forward. His two companions came similarly driven, until a pike-staff, taking one of them across the head, laid him senseless on the turf. They took him by the heels and hauled him out and along the alley, down which his fellows were now being swept. They dragged him down the steps into the little square, reckless of how they bumped his head, and at last abandoned him senseless on the plot of grass under the acacia trees. Prospero, following close upon their heels, had had no more thought here than elsewhere to wait for the thanks of those he had delivered. The urgency of his business never suffered him to linger.

And the men from his galleys, well disciplined and imbued with something of his own spirit, displayed all the promptitude and impartiality he could desire of them, dealing alike with all marauders, whether French or Genoese, clearing assaulted houses and sweeping the looters before them with many a bleeding head.

Late in the afternoon, when, weary and sickened by his task, Prospero could account it performed and order restored, he set out with his little band of followers to make his way at last to the ducal palace and present himself to his father.

They came by way of Sarzano, and thence climbed the steep ways that led to San Lorenzo and the ducal palace. Although of rapine there were no further signs, yet the city was naturally in a ferment, and Prospero’s progress lay through streets that were thronged and noisy with people most of whom were moving now in the same uphill direction.

As he advanced he was joined by successive bodies of his soldiers returning from similar labours, and one of these was led by Cattaneo. Before San Lorenzo was reached his following amounted to fully a hundred and fifty men. They made up a fairly solid phalanx, favourably viewed by citizens of the better sort, but scowled upon by the populace for the roughness of the repression they had used.

Doria’s methods had been more gentle. Whilst Prospero had dispatched five hundred men in twenty-five detachments of a score apiece to bludgeon the pillagers into decency, the Admiral had used two hundred men to form a line across half the city; then he had sent in four companies, each of a hundred men, with rolling drums and blaring trumpets, and it had needed little more than this loud advertisement of coming repression to put the delinquents to flight. The ruffians of the populace went to earth in their hovels, and the ruffians of Fregoso’s French troops made off as unobtrusively as they could to the quarters assigned to them in the great barrack opposite the Cappucini. Thus Doria had avoided arousing any of that fierce resentment of which Prospero perceived himself the object as he marched his swelling troop towards San Lorenzo.

There, in the square before the ducal palace, he found a throng so dense that it seemed impossible to cleave a passage through it. A double file of pikemen of Doria’s Provençal troops was ranged before the palace in a barrier to restrain the multitude, whilst from a balcony immediately above the wide portal a booming voice was compelling a hushed attention.

Looking up over the rippling sea of heads, Prospero recognized in the speaker a big man, grey-bearded and elderly, Ottaviano Fregoso, who had been Doge when last the French were in possession of Genoa. His heart was tightened by bewildered apprehension. For if the ducal chlamys in which Ottaviano Fregoso was now arrayed bore evidence of anything, it was that with the return of the French he had been restored to the ducal office. On his left stood his cousin Cesare Fregoso; on his right towered the majestic figure of Andrea Doria.

Holding his breath, so that he should miss no word that might explain this ill-omened portent, Prospero heard the fulsome terms in which Ottaviano was announcing that the Lord Andrea Doria, the first of their fellow-citizens, the very father of his country, was come to deliver Genoa from foreign oppression. No more should the Ligurian Republic be taxed in levies to maintain the Imperial armies in Italy. Those Spanish shackles were broken. Under the benevolent protection of the King of France, Genoa would henceforth be free, and for this great boon their thanks were due to the Lord Andrea Doria, that lion of the sea.

There he paused, like an actor inviting applause, and at once it came in roars of ‘Long live Doria!’

It was the Lord Andrea, himself, whose raised hand at last restored the silence in which Ottaviano Fregoso might continue.

He came to more immediate and concrete benefits resulting from the events. Grain ships were already unloading in the port, and there was bread for all. His cousin Cesare’s men were driving in cattle to be slaughtered, and there was an end to the famine they had been suffering. Again a rolling thunder applauded him; and this time the cry was: ‘Long live the Doge Fregoso!’

After that came assurances from Messer Ottaviano that the people’s sufferings should not go unpunished. Those responsible for all the misery endured should be called to account; those who, so as to maintain Genoa under the heel of a foreign tyrant, had not scrupled to subject the people to starvation should be brought speedily to justice. With a crude eloquence Ottaviano painted the maleficence of those who for their own unpatriotic ends had visited the city with those hardships, and he worked himself up into such a frenzy of indignation that very soon it was communicated to his vast audience. He was answered with fierce shouts of ‘Death to the Adorni!’—‘Death to the betrayers of the Republic!’

From the petrification of horror into which that speech, its insidious implications and its answering clamour, had brought him, Prospero was roused by a vigorous plucking at his sleeve, and a voice in his ear.

‘Well found, at last, Prospero. I have been seeking you these two hours and more.’

Scipione de’ Fieschi, flushed and out of breath, stood at his elbow.

‘Since you’ll have heard that mountebank, you’ll know what is doing; though hardly all, or you would not be here.’

‘I was on my way to the palace when this press brought me to a standstill.’

‘If you seek your father, you’ll not find him in the palace. He is in the Castelletto. A prisoner.’

‘God of Heaven!’

‘Do you wonder? The Fregosi mean to cast his head to the mob so as to ingratiate themselves. To destroy the old Doge is to make things safe for the new. Those who are loyal to the Adorni must be left without a rallying-point. Most logical.’ Abruptly, his eye ranged over the serried, ordered ranks aflash with steel that were now wedged into the throng. ‘Are these your men and can you trust them? If so, you had best act promptly if you would save your father.’

In a face white with distress Prospero’s lips parted to ask a question: ‘My mother?’

‘With your father. Sharing his prison.’

‘Forward, then. My men shall open me a way to the palace. I will see the Admiral at once.’

‘The Admiral? Doria?’ In his scorn, Scipione almost laughed. ‘As well make your appeal to Fregoso himself. It is Doria who has proclaimed him Doge. Words won’t avail here, my Prospero. This calls for action. Swift and prompt. The French troops in the Castelletto are not more than fifty, and the gates are open. This is your opportunity, so that you are sure of these men of yours.’

Prospero beckoned Cattaneo forward and gave an order. It was passed swiftly and quietly along the ranks, and soon that martial phalanx was writhing itself a way out of the press that hemmed it in. To go forward was impossible. It remained only to retreat and to take another road to the heights whence the Castelletto dominated the city.

IV THE CASTELLETTO

ON the balcony the new Doge was resuming his harangue; and because the stir of Prospero’s troop was not accomplished without some roughness and some noise, the mob would have passed from protests to menaces and perhaps to violence but for the formidable glitter of that compact and full-armed body.

They won out at last and gained the less encumbered spaces before the Cathedral, where, however, they still had to breast the stream of townsfolk advancing in the opposite direction. Beyond that space, as they ascended a steep street leading to the Campetto, they moved more freely and in orderly formation, their pikes at the slope. Active interference with them none dared to venture. But more than once, recognized for the foreign troops of Prospero Adorno, responsible for the harsh measures of that day, jeers and insults greeted and followed them from some of those who had been repressed. Answering taunt with laughing taunt as they marched, they pressed on, Prospero in the rear with Scipione, his countenance white and wicked.

In the Campetto they were met by another of Prospero’s captains, who with some sixty men he had assembled was on his way downhill in quest of the main body. Thus when at last Prospero reached the red walls of the Castelletto, flushed now by the setting sun, he brought at his heels a force more than two hundred strong.

The arched gateway yawned open, and they went through at the double. The men who sprang forth to challenge them as their accelerated steps clattered past the gatehouse were swept aside like twigs on the edges of a torrent.

In the courtyard, one half of which lay already in shadow, more men confronted them, and the officer in charge, a Provençal of Doria’s following, recognizing the Pontifical Captain, stepped forward briskly.

‘In what can I serve you, Sir Captain?’ The deference of the question was purely mechanical. The Provençal knew enough of what had happened that day in Genoa to be made uneasy by this invasion in strength.

Prospero was short. ‘You will place the Castelletto in my charge.’

Dismay overspread the man’s swarthy countenance. It was a moment before he found his voice. ‘With deference, Sir Captain, that I cannot do. Messer Cesare Fregoso has placed me in command here, and here I must remain until Messer Cesare relieves me.’

‘Or until I sweep you out. You’ve heard me, sir. Willingly or unwillingly, you’ll obey.’

The officer attempted bluster. A big man, his proportions seemed to swell. ‘Sir Captain, I cannot take your orders. I——’

Prospero waved his attention to the men now in ordered ranks behind him. ‘There is the argument that will compel you.’

A gloomy laugh followed upon a grimace of malevolence. ‘Ah, ventrebleu! If you take that tone, what can I do?’

‘What I bid you. It will save trouble.’

‘For me, perhaps. But for you, sir, it may make it.’

‘That is my affair, I think.’

‘I hope you’ll like it.’ The fellow swung on his heel, bawling orders in a voice like a trumpet call. Men came at the double in response to it, formed their ranks across the courtyard, and within ten minutes were marching out of the fortress to the tune of ‘En Revenant d’Espagne.’ The officer going last swept Prospero a bow that was full of mockery and the menace of things to come.

Prospero went in to find his father, and was led by Scipione up a narrow stone staircase to a portal guarded by two sentries, who were summarily dismissed to rejoin their company. Then Prospero unlocked the door, and across an antechamber bare as a prison, came to that little closet tapestried in blue and grey.

On a day-bed set under one of those narrow windows that commanded a view of the city, the harbour, and the gulf beyond, Antoniotto Adorno reclined in a drowsiness of exhaustion. Despite the heat he was wrapped in a long black houppelande that was heavy with dark fur. His lady, slim and youthful in a stiff, high-corsaged gown of purple shot with gold, occupied an armchair at the head of his couch.

A table in mid-chamber was encumbered with the remnants of the very simplest of meals: the half of a loaf of rye bread, a hemisphere of Lombard cheese, a dish of fruit—figs, peaches, and grapes—from some patrician garden, a tall silver beaker of wine, and some glasses.

The creak of the door on its hinges roused Monna Aurelia. She looked over her shoulder and her face went pale under the black, peaked head-dress at the sight of Prospero almost hesitant upon the threshold. Then she was on her feet, with heaving bosom and a cry that caused her lord to raise his heavy eyelids and look round in his turn. Beyond a wider opening of the kindly, generous old eyes, Antoniotto’s countenance showed no change. His voice spoke so quietly that it was impossible to suspect any emotion.

‘Ah! It is you, Prospero. You arrive at a sad moment, as you see.’

But if his father had no further reproach for him, Prospero in that hour was not disposed to be tender with himself. ‘You may marvel, sir, that I should come at all.’ He advanced, Scipione following and closing the door.

‘No, no. I hoped you would. You will have something to tell me.’

‘Only that you have a fool for a son, which will be no news to you, unless you have supposed him also a knave.’ He was bitter. ‘I was too easily duped by that rascal Doria.’

Antoniotto’s nether lip was protruded deprecatingly. ‘No more easily than I,’ said he, and added: ‘Like father, like child.’

Shamed as no invective could have shamed him, Prospero’s pained eyes sought his mother. In a whirl of maternal emotion, she was holding out her hands to him. He stepped quickly to her, caught them in his own, and bowed to kiss each of them in turn.

‘For once your father is just,’ she greeted him. ‘Your fault is no worse than his own, as he says. His obstinacy is to blame for all.’ Her voice hardened shrewishly. ‘He should have done the will of the people. He should have surrendered when they desired it. Then they would have supported him. Instead, he left them to starve into exasperation, and then to mutiny against him at the bidding of the Fregosi. That is where the blame lies.’

Thereafter they wrangled fruitlessly; she intent upon being his advocate, Prospero insistently self-condemnatory. Antoniotto listened listlessly, almost drowsily. At last Scipione, calmly critical spectator, reminded them that it was more important now to discover an issue from their peril than to dispute as to how it had arisen.

‘The issue at least I can provide,’ Prospero asserted. ‘To that extent I can repair my fault. I have a sufficient force at hand.’

‘Is that an issue?’ cried his mother. ‘Flight? Forsaking everything? A fine issue that for the Doge of Genoa, leaving the Fregosi and these Doria rogues triumphant.’

‘In the pass to which things have come, Madonna,’ ventured Scipione, ‘I’ld be glad even to be sure of that for you. Do you suppose, Prospero, that you have men enough? That you will be suffered to reach your galleys? Or, if you reach them, that Doria will allow you to depart?’

Antoniotto roused himself. ‘Ask, rather: Will the Fregosi? It is they who are now the real masters. Can you doubt they will require that no Adorno be left alive to come back and dispute their usurpation?’

‘Whilst I hold this fortress——’

‘Dismiss the thought,’ his father interrupted him. ‘You cannot hold it for a day. Troops must be fed. We are without victuals.’

This was a stab in the back to all Prospero’s hopes. Blank consternation overspread his face. ‘What, then, remains?’

‘Since we haven’t wings, or even a flying-machine, like that idiot who broke his neck off the Tower of Sant’ Angelo, it remains only to recommend our souls to God.’

And there they might have left it had not Scipione brought his wits to their assistance. ‘Your way out,’ he said, ‘lies not in force through the city, but alone by way of the open country.’

Under their questioning eyes he explained himself. The eastern face of the Castelletto rose upon the wall of the city itself. From the roofed battlements that crowned the summit of the fortress to the rocks at the base of the city wall it was a cliff of seventy feet of masonry.

‘You will leave Genoa,’ said Scipione, ‘as Saint Paul left Damascus. In default of a basket, a cradle is easily made, and easily lowered by ropes.’

Antoniotto’s eyes remained unresponsively dull. He reminded them of his condition. His wound put it beyond his power to go that way. It had drained his strength. Besides, what did he matter now? Having lost all that he valued, he was ready to face with indifference whatever might follow. He would be glad, he assured them with a sincerity they could not doubt, to come to rest. Let Prospero and his mother make the attempt, unencumbered by a sick and helpless man.

Neither Prospero nor his mother, however, would give heed to this. Either he went with them or they remained with him. Confronted with these alternatives, Antoniotto ended by yielding, and it remained only to prepare for flight.

By dusk all was ready, and later, under cover of darkness, the improvised cradle, bearing each of the three fugitives in turn, was lowered from the battlements by men acting under the directions of Scipione.

Thus furtively ended the Adorno rule in Genoa, and whilst Madonna Aurelia raged against Doria and Fregosi alike, Prospero reviled only himself for having been used as the instrument of the perfidy that had encompassed the ruin of the father whose faltering steps he supported in that ignominious flight.

V THE BATTLE OF AMALFI

IT was in the first days of August of 1527 that Doria took possession of Genoa for the King of France, and Prospero Adorno, in flight from the city, abandoned his command of the Papal Navy.

Less than a year later—towards the end of May of 1528—we find him in Naples, as an Imperial Captain, serving under Don Hugo de Moncada, the Emperor’s Viceroy.

His father had perished miserably, be it from an aggravation of his infirm condition as a result of hardships endured in the escape, be it from a loss of the will to live, be it from a combination of the two. He was a dying man when at last they had reached Milan and the shelter which Antonio de Leyva, the Imperial Governor, so readily afforded them. There, in the great castle of Porta Giovia, Antoniotto Adorno had yielded up his life within three days of arrival.

The first explosion of his widow’s grief was of a violence that took Prospero by surprise. Reluctantly he had regarded his mother as one who loved herself too well to be deeply stirred by whatever might happen to another, no matter how near of kin. In the hour of his own grief he found some consolation in that under the hard surface of his mother’s nature a depth of feeling made of their bereavement a bond between them.

All of a day and a night she was in a state of prostration. But thirty hours after Antoniotto’s death she came, in black velvet, to stand with Prospero beside his father’s bier.