6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

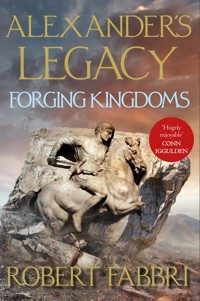

'This may be the greatest tale of the ancient world. Hugely enjoyable' CONN IGGULDEN An empire in turmoil. A throne for the taking. Alexander the Great's sudden and unexpected death has left the largest, most formidable empire the world has ever seen leaderless. As the fight to take control descends into ruthless scheming and bloody battles, no one - man, woman or child - is safe. As wars on land and sea are lost and won, and promises are made only to be broken, long-buried secrets come to light in the quest for the true circumstances surrounding Alexander's death. Was he murdered, and if so by whom? Could he have been sowing the seeds of discord deliberately, through his refusal to name an heir? And who will eventually ascend to power at the helm of the empire - if it manages to survive that long? Can one champion vanquish all...? 'An excellent new series by the consistently brilliant Robert Fabbri' Sunday Sport

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Robert Fabbri read Drama and Theatre at London University and worked in film and TV for twenty-five years. He has a life-long passion for ancient history, which inspired him to write the bestselling Vespasian series and the Alexander’s Legacy series. He lives in London and Berlin.

Also by Robert Fabbri

ALEXANDER’S LEGACY

TO THE STRONGEST

THE VESPASIAN SERIES

TRIBUNE OF ROME

ROME’S EXECUTIONER

FALSE GOD OF ROME

ROME’S FALLEN EAGLE

MASTERS OF ROME

ROME’S LOST SON

THE FURIES OF ROME

ROME’S SACRED FLAME

EMPEROR OF ROME

MAGNUS AND THE CROSSROADS BROTHERHOOD

THE CROSSROADS BROTHERHOOD

THE RACING FACTIONS

THE DREAMS OF MORPHEUS

THE ALEXANDRIAN EMBASSY

THE IMPERIAL TRIUMPH

THE SUCCESSION

Also

ARMINIUS: LIMITS OF EMPIRE

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Corvus,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Robert Fabbri, 2021

Map and illustrations © Anja Müller

The moral right of Robert Fabbri to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 800 7

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 801 4

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 802 1

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

To my daughter, Eliza, and her husband-to-be,Tom Simpson, wishing you both every happiness in your lives together.

A list of characters can be found on page 410.

PTOLEMY.THE BASTARD.

ARMIES ALWAYS COMPLAIN, Ptolemy mused, stepping out of the boat and over a severed arm washed up on the eastern bank of the Nile, but this one has more cause than most. With a smile and a nod he acknowledged the Macedonian officer, ten years his junior, in his mid-thirties, awaiting him with two horses; a mounted escort stood a few paces off, the rich glow of the westering sun on their faces. ‘They are ready to talk, I take it, Arrhidaeus?’

‘They are, sir,’ Arrhidaeus replied, offering his hand as Ptolemy slipped on the mud edging the blood-tinged waters of Egypt’s sacred river.

Ptolemy waved away the proffered help. ‘The question just remains as to who will lead their delegation, Perdikkas or one of his senior officers?’

‘I spoke with Seleukos, Peithon and Antigenes; they agree that Perdikkas is the obstacle to peace and, therefore, if his intransigence continues, he needs to be removed.’

Ptolemy grimaced at the idea, rubbing his muscular neck and then clicking it with a swift head movement. ‘It would be better for all of us if he can be induced to negotiate sensibly; there’s no need for such extreme measures.’ He gestured up and down the riverbank, strewn with bodies in various states of dismemberment; the work of the river’s many crocodiles. ‘Surely having lost so many of his lads trying to cross the Nile he will see sense and withdraw with a face-saving compromise.’

‘He’ll never forgive you for hijacking Alexander’s funeral cortège and taking it to Egypt; his officers don’t think he will come to the table unless you give it back to him.’

‘Well, he won’t get it.’ Ptolemy grinned, his dark eyes twinkling with mischief. ‘Perhaps I’m the one who is being intransigent, but it’s for my own sake; interring Alexander’s body in Memphis and then moving it to Alexandria once a suitable mausoleum has been built gives me legitimacy, Arrhidaeus.’ He thumped his fist on the boiled-leather cuirass covering his chest. ‘It proclaims me as his successor in Egypt and I fully intend to stay here. Perdikkas is welcome to whatever else he can hold but he won’t get Alexander back and he won’t get Egypt.’

‘Then my feeling is that he won’t be at the negotiations.’

‘Unfortunately, I think you’re right. He was a fool, was Perdikkas; he should have kept the body in Babylon and concentrated on securing his position in Asia rather than attempting to get the whole empire by taking Alexander home to Macedon. Everyone knows that Kings of Macedon have traditionally buried their predecessors; he wanted to be king of us all: unacceptable.’

‘Which is why you were right to take the body.’

‘It wasn’t just me, my friend. You were the one in command of the catafalque; you allowed me to steal it from Perdikkas.’

‘It was a pleasure just to imagine the expression on the highhanded, arrogant bastard’s face when he heard.’

‘I wish that I’d actually seen it, but it’s too late now.’ Ptolemy sucked the air through his teeth, taking his horse’s bridle and stroking its muzzle. ‘That it should have come to this,’ he confided to the beast, ‘Alexander’s followers killing each other over his body.’ The horse snorted, stamping a foot. Ptolemy blew up its nostrils. ‘You’re wise to keep your own counsel, my friend.’ Ptolemy looked over to the Perdikkan camp, a little more than a league distant, hazed by the heat and the smoke from many cooking fires, and then heaved himself into the saddle. ‘Shall we go?’

Arrhidaeus nodded and mounted, then eased his horse into a gentle trot. ‘Just before I sent the message for you to cross the river, Seleukos guaranteed your safety in the camp and said that you would be allowed to address the troops. He’s very keen to come to an accommodation with you.’

‘I’m sure he is. He’s the most ambitious of Perdikkas’ officers; I almost like him.’

‘And I’m sure that he almost likes you.’

Ptolemy threw his head back, laughing. ‘I’ll be needing as many almost-friends as I can get. I imagine he’ll be looking for something lucrative: Satrap of Babylonia, for example – should the post become vacant and we get rid of Archon, Perdikkas’ nominee, that is.’

‘I would say that is exactly what he wants. Like all ambitious men he can see opportunity even in defeat.’

‘Perdikkas and his allies may have lost to me here in the south but not in the north; they still haven’t heard that Eumenes defeated and killed Krateros and Neoptolemus.’

A conspiratorial smile played on Arrhidaeus’ lips. ‘If they had then I’d wager that they would not be in the process of assassinating their leader should he not agree to talks.’

Ptolemy shook his head, frowning, unable to suppress the regret he felt at the murder of a fellow member of Alexander’s bodyguard, seven in number. ‘That it should really come to this and so soon; once we were brothers-in-arms, conquering the known world, and now we slip blades between each other’s ribs, and all because Alexander gave Perdikkas his ring but then refused to name a successor. Perdikkas the Half-Chosen now becomes Perdikkas the Fully-Dead.’ He leaned over and clapped Arrhidaeus on the shoulder. ‘And, I suppose, my friend, that you and I must bear a lot of responsibility for his death.’

Arrhidaeus spat. ‘He brought it upon himself by his arrogance.’

Ptolemy could see the truth of that statement. In the two years since Alexander’s death in Babylon, Perdikkas had tried to keep the empire together by assuming command in a most highhanded manner purely because Alexander had given him the Great Ring of Macedon on his deathbed saying: “To the strongest”, but neglecting to say exactly whom he meant by that.

Ptolemy had realised immediately that the great man had sown the seeds of war with those three words and he suspected that he had done so deliberately so that none would out-shine him. If it had been an intentional ploy it had worked magnificently, for the previously unthinkable had happened: Macedonian blood had been spilt by former comrades-in-arms within eighteen months of his passing. Indeed, war had flared almost immediately as the Greek states in the west had rebelled against Macedonian rule and the Greek mercenaries stationed in the east had deserted their posts and marched back west. More than twenty thousand had joined in one long column and headed home to the sea; they had been massacred to a man, at Seleukos’ instigation, at the Caspian Gates as a warning to others seeking to take advantage of Alexander’s death.

In the west, the Greek rebellion had been crushed by Antipatros, the aged regent of Macedon, but not without considerable difficulty having been defeated and forced to withdraw to the city of Lamia and there endure a winter siege. It had been the vain and foppish Leonnatus who had come to his aid, breaking the siege, but he had lost his life in the process thus becoming the first of Alexander’s seven bodyguards to die. Antipatros had regrouped back in Macedon and, with the help of Krateros – Macedon’s greatest living general, the darling of the army – had defeated the rebellion and imposed a garrison and a pro-Macedonian oligarchy upon Athens, the city at its head.

With the west secured, Antipatros had then declared war on Perdikkas for marrying and then repudiating his daughter, Nicaea, at the same time as conspiring to marry Kleopatra, the full sister of Alexander. And thus the first war between Alexander’s successors had commenced with the diminutive Eumenes, Alexander’s former Greek secretary, and now Satrap of Kappadokia, supporting Perdikkas. But Eumenes had been unable to prevent Antipatros and Krateros crossing the Hellespont into Asia due to the defection of Kleitos, Perdikkas’ admiral. Underestimating Eumenes’ martial abilities, Antipatros and Krateros had made the fatal mistake of dividing their forces: Krateros had been despatched to deal with the Greek whilst Antipatros had headed south to confront Perdikkas. But the wily little Eumenes had shown a degree of generalship that had not been expected of a man who had held no significant military command and, despite his former ally, Neoptolemus, switching sides, he had defeated Krateros, killing the great general and the treacherous Neoptolemus in the process.

This fact was, as yet, only known to Ptolemy as it was his navy that controlled the Nile and he had prevented the news getting quickly through to Perdikkas’ camp: had they known of their victory in the north and that Antipatros’ army was now between them and Eumenes, their willingness to make peace might have been severely dampened.

And thus was Ptolemy a man in a hurry.

SELEUKOS.THE BULL-ELEPHANT.

SELEUKOS GLANCED AT the blood coating the naked blade clasped in his fist as he stepped out into the crowd surrounding Perdikkas’ tent; broad-shouldered, bull-necked and a head taller than most men, he looked down at the, mainly, full-bearded faces around him, most in their forties or older – at least ten years his senior. All were veterans of Alexander’s campaigns and all now found themselves fighting for Perdikkas against fellow Macedonians who, by force of circumstance, were in Ptolemy’s army. It had been the promise of a share in Egypt’s riches that had motivated these men to turn on their former comrades; but those former comrades had defeated them, denying them passage across the Nile. Many had been swept away when the silt on the river’s bed had been dislodged by the army’s elephants that Perdikkas had ordered into the river upstream of the crossing in an attempt to slow the current; the disaster had attracted crocodiles who had relished the feast that had resulted from this blunder. And so it was in anger that the crowd jostled around their commander’s tent, anger for the grisly death meted out to many of their fellows; to die in the maw of a reptile having conquered so much of the world was a fate unacceptable to Alexander’s proud veterans – and it was clear to them who had been responsible.

‘What have you done?’ a voice to his right growled.

Seleukos turned to see Docimus, ever faithful to Perdikkas, walking towards him with his hand on the hilt of his sword. ‘I’d turn around if I were you and go to find your little friend, Polemon, and get out of here before you get lynched, Docimus; your protector is dead.’ He held up the bloodied knife. Behind him, Peithon and Antigenes, they too with blood on their hands, smiled, thin and threatening. Docimus paused, looking again at the blood before walking away at pace.

Seleukos turned, dismissing Docimus from his mind as an irrelevance; he had a far more important task to accomplish. Feeling no fear, he stepped up onto a cart and held his bloodied dagger above his head; behind him, Peithon and Antigenes, his two fellow conspirators, joined him on the makeshift dais. They will either lynch us or laud us; yesterday it would have been the former but after today’s debacle I rather suspect it will be the latter. At the sight of Perdikkas’ three most senior officers openly acknowledging their guilt in the assassination of the bearer of Alexander’s ring, received from his own hand upon his death bed, the veterans growled their approval – an act unthinkable just two years previously, soon after the great man’s untimely demise. But then two years previously it would have been unthinkable that a Macedonian should spill a fellow-countryman’s blood.

So much had changed.

‘Perdikkas is dead,’ Seleukos announced, his voice high and resounding so that it carried over the few thousands in the large crowd. ‘We three took it upon ourselves to remove the one obstacle to peace; the man whose arrogance has caused the deaths of so many of our comrades. The man who recklessly married and then repudiated Nicaea, the daughter of Antipatros, the regent of Macedon, thus setting Asia against Europe; the man who then intrigued to marry Kleopatra, Alexander’s full sister, in order to make himself king. King! King, when he was sworn to be the regent for his two wards, the rightful kings, Alexander and Philip.’ Out of the corner of his eye he caught sight of two women turning away, with their retinues, and each making their separate ways back to their tents: Roxanna, the mother of three-year-old Alexander, the fourth of that name, and Adea, now known as Queen Eurydike since her marriage to Alexander’s imbecilic half-brother Philip, the third king of Macedon to be thus called. Now that you know just what your erstwhile protector really had in mind, you might both find it politic to be a little more grateful and a little less vocal, bitches. ‘I suggest that in the spirit of reconciliation and in acknowledgement of Perdikkas’ folly – a folly that we all shared in – we should ask Ptolemy to act as the regent of the two kings.’ He studied his audience but could find no trace of dissent. I think that I may have timed this just right. If they’ll not object to my suggestion that Ptolemy become regent then I’m sure that he’ll show his gratitude by giving me Babylonia in return. It’s down to Ptolemy to continue in a spirit of reconciliation. ‘Ptolemy, our brother whom, through a collective madness stoked by Perdikkas, we were forced to fight, is coming across the river to talk peace; we shall ask him then.’ Mutterings of agreement greeted this statement. ‘Kassandros is also here.’ He pointed to where he had last spoken to Antipatros’ eldest son just before he had entered Perdikkas’ tent, and failed to spot his pinched, pock-marked face in the crowd. ‘He comes with an invitation from his father, Antipatros, for us all to meet at The Three Paradises in the cedar hills above Tripolis in Syria and there we shall make a final settlement.’ He paused for the expected cheer, only to be disappointed by its volume.

‘A settlement to include all,’ Kassandros shouted, springing onto the cart behind Seleukos, taking him by surprise. He smiled at the crowd with all the charm of a rabid dog, his pale, sunken eyes, either side of his beak of a nose, dead to emotion; with lanky, spindly legs, narrow shoulders and a weak chest, he looked out of place in the richly decorated cuirass and pteruges of a Macedonian general, an avian error in uniform, and yet he had a presence that could command attention; the crowd stilled. ‘My father has called for all the satraps from all over the empire to be present, even Eumenes, despite – or perhaps because of – his support for Perdikkas. My father and I are determined that never again shall Macedonian fight Macedonian! My father and I will ensure that you, brave soldiers of Macedon, will never again suffer at the hands of your comrades.’

The cheer thundered into the darkening sky as Kassandros held both arms aloft, hands clasped, as if he had just won a wrestling bout at the games.

Seleukos shared a brief, but significant, look with Antigenes and then smiled at Kassandros, placing a well-muscled, hirsute arm around his tall but wiry frame. I can see that I’m going to have to watch you, my ugly worm; no one gets a louder cheer than me from my own men and expects to go un-humiliated. ‘That was well said, Kassandros,’ he shouted for all to hear. ‘I can see we have a common purpose.’ Although his response was positive, one look from Kassandros’ pinched face was enough to disabuse Seleukos of the notion; a fact that did not surprise him. And what would I possibly want to achieve with you? He turned back to the crowd and gestured for silence. ‘For now, though, we will mourn our dead and at dawn tomorrow we will convene an army assembly and there we will hear what Ptolemy has to say.’

‘Is it right to allow Ptolemy to address the men?’ Antigenes asked, as he, Seleukos, Peithon and Kassandros waited for the Satrap of Egypt to arrive; night was falling and, with it, the temperature. A dozen lamps and a couple of braziers heated the command tent and lit the dark blood stain on an eastern-made carpet, testimony to the crime committed not three hours previously; the hard evidence, the body itself, had been removed in secret to prevent it becoming a focus for dissent of the new regime.

‘What choice do we have?’ Seleukos countered, downing a cup of wine in one.

‘You say “we” but it was actually only you who gave your word to Arrhidaeus; and you did so without consulting Peithon or me.’

‘I gave you both the chance to object but neither of you did.’ Seleukos waved away the criticism. ‘Anyway, Ptolemy has to be allowed to speak. He has Alexander’s body; he must defend his taking it. When he justifies his actions then he makes Perdikkas’ decision to go to war with him even more dubious.’

‘And if Ptolemy can’t explain himself to the men’s satisfaction?’ Kassandros asked.

Seleukos grunted and gave a half-smile. ‘Have you ever known Ptolemy to be unable to talk his way out of a situation?’ He stopped abruptly, as if he had just remembered something of vital importance. ‘Oh, of course, silly me; you were left behind in Macedon weren’t you, Kassandros? So you probably hardly remember him at all anymore; although you did briefly know him during the few months after Alexander’s death before he went to Egypt.’ Seleukos feigned a look of concentrated recollecting. ‘You were in Babylon at that time, weren’t you?’

‘You know perfectly well that I was.’

‘Of course, I remember now; you arrived the day before Alexander fell ill. You’d come all the way from Pella because Alexander had sent Krateros to replace your father as regent of Macedon and you were bearing a letter from him asking for confirmation of the order. Strange, we all thought, Antipatros sending his son as a post boy when anyone would have done; especially as the mere sight of your face would have been enough to send Alexander into a fury, such was his aversion for you.’ He smiled pleasantly at the scowling Kassandros. ‘Still, it didn’t matter in the end, did it? Alexander was dead within three days of your arrival.’ He gave Peithon and Antigenes a knowing look. ‘Conveniently.’

Kassandros sprang to his feet. ‘What are you insinuating?’

Seleukos motioned for him to sit back down. ‘Nothing, Kassandros, nothing at all. Your younger brother, Iollas, was Alexander’s cup-bearer; allowing him to mix his wine and water shows just how much trust Alexander placed in your family, despite his hatred for you personally.’

Kassandros shot Seleukos a look of pure loathing, but slowly backed down as the bigger man casually cracked his knuckles.

‘I mean nothing by it, my friend,’ Seleukos said, refilling his cup with un-watered wine and shrugging his shoulders. ‘Nothing at all. But there could be more than a few who might make some unwarranted connections should rumour run unchecked. Wouldn’t you agree, Antigenes?’

The veteran general scratched at his bald pate, sucking on his lip, as if he were considering a matter of great import. ‘Yes, I’d agree. A few of my lads have already wondered at the coincidence but I’ve told them not to be so suspicious and I still have to keep on doing so from time to time.’

Seleukos gave him a look of sympathy. ‘It would be a shame if you stopped.’

‘Oh, I don’t think that I would do that.’

Seleukos nodded in agreement. ‘No, I don’t think that you would, not unless someone tried to make himself too popular with our lads, giving rousing speeches and getting hearty cheers.’ He looked directly at Kassandros. ‘Then we might have to, how should I put it? Poke the embers of rumour?’

‘You wouldn’t. Especially when you know that I had nothing to do with Alexander’s death.’

‘Do I, though? Do I really know that you had nothing to do with it?’ Seleukos looked at Peithon. ‘Do you, Peithon?’

Peithon frowned, his slow mind turning at full speed. ‘I don’t know.’ He frowned again. ‘Do I?’

‘Never mind. Antigenes, what about you?’

‘At the moment I know that he had nothing to do with it,’ Antigenes asserted, but then raised a warning finger. ‘But if he were to come between us and our lads again, as he did just now, then new evidence might well come to light.’

‘You bastards,’ Kassandros spat. ‘People from country families like you, bumpkins with sheep shit on your cocks, threatening me, the son of the regent of Macedon; how dare you?’

‘How dare we?’ Seleukos looked incredulous. ‘My father, Antiochus, was one of Philip’s generals, as was Peithon’s father, Creteuas. Antigenes may have worked his way up from the ranks but is now highly respected throughout the army; don’t forget that until recently he was one of Krateros’ senior officers and you don’t climb much higher than that in this army. We dare threaten you, Kassandros, because for all your father’s fine words about peace and cooperation, we don’t like you wheedling your way into favour with our men; we don’t want you gaining their loyalty and we don’t want you becoming a contender. Another contender is not what the empire needs at this time.’ He held out his hand. ‘The ring, please.’

Kassandros looked shocked. ‘What?’

‘Alexander’s ring, please. Don’t play dumb; I know you’ve got it. We three came out of Perdikkas’ tent leaving him dying with his ring still on his finger, but when we had the body removed it was gone. I looked for you outside as I was addressing my men and you were absent, only to suddenly appear behind me on the cart, coming from the direction of the tent. The ring, please.’

Kassandros did not move.

‘You’re a dead man if you try to leave this tent with it; we killed Perdikkas today, Kassandros. For all his faults he was a great man in many ways. I don’t think any of us would notice the passing of a turd like you. The ring!’

Slowly Kassandros opened a pouch on his belt, his eyes blazing his fury at Seleukos. He pulled out the Great Ring of Macedon, indented with the sixteen-point star-blazon, weighed it in his hand and then tossed it at Seleukos as if it were of little consequence.

Seleukos grabbed the ring out of the air.

‘Good evening, gentlemen,’ Ptolemy said as the guard let him and Arrhidaeus through the entrance. He cast his eyes around the company. ‘Nothing troubling you all, I hope? What was that that Kassandros just gave you? A ring, if I wasn’t mistaken? Rather a big one at that.’ He looked with exaggerated disapproval at Kassandros. ‘What was such a weak man doing with so big a ring?’

Kassandros jumped to his feet. ‘Don’t you talk to me like that, Ptolemy!’

‘Like what?’ Ptolemy asked, surprised. ‘I was merely stating the facts: it is a big ring and you are a weak man. Not small like Eumenes, I grant you, but weak nonetheless. Why, you haven’t even killed your first wild boar.’

Kassandros sneered. ‘You think that you’re all so clever and that you can bait me because I didn’t share in the greatest adventure of the age, because I stayed behind. Look at Kassandros, he’s a weakling. He hasn’t even killed a wild boar on a hunt let alone faced a Persian army in battle; he’s nothing but someone to jeer at. Well, I’ll tell you what, brave heroes: I may not have the right to recline at the dinner table because I’ve never taken my boar, and you might think that I feel the shame every meal, sitting upright on the couch like a youth with the first growth of hair on his lip. And you may suppose that I regret, every day, being left behind by Alexander because he could never tolerate me for the weakness that he – wrongly – perceived in me. But you would be mistaken because, you see, I don’t think the same way as you.’ He smiled, baring caninesque teeth. ‘I take no pleasure, nor hold any worth, in hunting or feats of valour on the field of battle, why should I? I’m not built for it as you all endlessly observe. My priorities are different and, gentlemen, soon you will find out that they are superior.’ He turned and walked from the tent without looking back.

‘That seemed to hit a nerve,’ Ptolemy remarked with a bemused look. He turned to Seleukos. ‘I assume that’s Alexander’s ring.’

‘It is,’ Seleukos said, holding it out to Ptolemy.

‘So I assume that Perdikkas is dead, seeing as he’s not here and yet the ring is.’

‘We had no choice.’

Ptolemy took the ring and slipped it on the end of his forefinger. ‘What was Kassandros doing with it?’

‘He’d stolen it from Perdikkas’ corpse and thought that I wouldn’t notice.’

‘Had he now? I wonder what he meant to do with it; give it to his father or keep it for himself?’

‘Give it to his father, surely,’ Antigenes asserted.

Ptolemy looked at the veteran, unconvinced, as he sat in Kassandros’ vacated chair. ‘After that little exhibition, I’m not so sure; I would speculate that the little weasel has high ambitions.’

‘Delusions of grandeur,’ Arrhidaeus said, also sitting.

‘Weakling!’ Peithon snapped.

‘Never underestimate a man who feels that he is alone against the rest of the world; Kassandros is one such like, if ever I saw one. Unfortunately, he can’t be got rid of without seriously upsetting his father and I’d say that is best avoided at the moment, wouldn’t you?’ He took the ring from his finger and leaned over to hand it back to Seleukos. ‘What are you going to do with it?’

Seleukos glanced at his two companions, who both indicated acquiescence. ‘At the moment I hold it, but we had thought of offering the regency of the two kings to you.’

‘To me?’ Ptolemy laughed in genuine amusement. ‘And what would I do with the regency? Why would I want to bother myself with that burden when I already have Egypt and Cyrenaica? What possible pleasure could I get from having a toddler along with its vicious, poisoning mother, as well as an idiot and his ambitious queen under my protection?’

Seleukos’ face betrayed genuine surprise. ‘But we thought you would be grateful.’

‘Grateful? Grateful enough to offer you Babylonia? Is that what you hoped?’ Ptolemy grinned at the sight of Seleukos’ discomfiture. ‘Come, Seleukos, you don’t really imagine that I want to set myself up as a second Perdikkas, do you? No one can hold the empire together as he proved so convincingly. No, Seleukos, I’ll be happy for you to have Babylonia, and I know that is what you want as I’ve watched – and been impressed by – your manoeuvring to becoming the obvious choice to take it when Perdikkas inevitably fell; but you won’t get it from my hands. You keep the ring and give yourself Babylonia.’

Seleukos looked at the ring and then back to Ptolemy. ‘I don’t want it.’

‘Of course you don’t; for the same reason as I don’t. So let us come to an elegant solution, you and I: let us appoint deputies, one each who will share the regency; if I were you I would nominate Peithon as I believe he owes you a big favour for the way you massacred those twenty thousand Greeks before he was tempted to incorporate them into his army and go into open rebellion. As he owes you his life it is the least he can do.’

Peithon scowled.

Seleukos contemplated the notion for a moment, smiling. ‘Of course, Peithon would be perfect because he is so unsuited to the position.’

‘But he’ll do until a full council can convene. I believe Antipatros has summoned you all to The Three Paradises, you can all decide then who should be regent together.’

‘“You”? Surely you mean “we”?’

‘No, Seleukos, I mean you. I won’t be going. In fact, I don’t think I’ll ever leave Egypt again unless to travel to one of her domains. I have all I need. And Peithon can give you what you want.’

Seleukos nodded. ‘All he has to do is to confer Babylon on me and then Antipatros will find it impossible to take it away unless he wants to go against the spirit of cooperation that he is hoping to achieve at The Three Paradises.’

‘Exactly. And your position will be made so much the stronger by an endorsement from my nomination: Arrhidaeus.’

‘What!’ Arrhidaeus turned to Ptolemy in alarm. ‘Why do you choose me?’

‘By way of thanking you, of course; you surrender your part of the regency to Antipatros and he will reward you with a satrapy, something I can’t do. I’m sure there’ll be a vacancy soon; in fact, we both know that one has already become free.’

Arrhidaeus’ eyes widened. ‘Ah.’

Seleukos frowned. ‘What? What do you know that you aren’t telling us?’

Ptolemy shrugged. ‘Well, I suppose you would have found out sooner or later, but eight days ago Eumenes defeated and killed Krateros.’

Seleukos, Antigenes and Peithon stared, incredulous, at Ptolemy.

Seleukos was the first to recover. ‘That’s impossible.’

‘Evidently not. To make it all the more impressive, Neoptolemus changed sides; Eumenes captured his army’s baggage and then killed Neoptolemus in single combat before taking the combined army on to face Krateros. Apparently he didn’t let his Macedonian troops know who they were facing; Krateros fell to his Asian cavalry. Now he’s dead, the satrapy of Hellespontine Phrygia is vacant.’

‘But if Perdikkas and we had known that his cause had won in the north…’

‘He probably wouldn’t be dead now. I know; that’s why I kept it from you.’

Seleukos’ huge frame tensed with anger. ‘You scheming bastard!’

‘Am I? Perhaps I am. I’m certainly a bastard and I suppose I could be accused of scheming. But I had to make sure that we could all talk sensibly: had Perdikkas known of Eumenes’ victory it wouldn’t have made much difference to his position, other than to have strengthened his unwillingness to negotiate; but you three would certainly have been much more averse to assassinating him. In fact, I don’t think that you would have.’

‘You forced us to kill him.’

‘I wouldn’t say forced but, yes, I did do my best to ensure that you would if he proved to be intransigent. And I think that we’ll all find that it was for the best. Now, shall we eat? I’m tired as I fought and won a battle today and in the morning I have to address your men.’

ADEA.THE WARRIOR.

IT WAS MORE imperative than ever that she should conceive now; her life depended on it. Adea cursed the necessity that was so repugnant to her. In the six months that she had been married to King Philip and become Queen Eurydike, she had only allowed him to cover her at the height of her cycle every month and each time the experience brought her to the point of vomiting: the masculine stench, the bestial grunting, the drool flowing from his slack lips dripping onto her buttocks and the humiliation of kneeling before him as he grunted his way to his pleasure, with no thought of her own; none of the tenderness that she found in the female lovers that she took to her bed throughout the rest of the month. Still, it was better than lying on her back and having to endure his breath as well.

But now she knew that she would have to resign herself to the experience more than just once a month, for if what Seleukos had said was the truth – and she had no reason to disbelieve it – then she really did need the weapon of a child, a son. A son who could claim to be the grandson of Philip, the second of that name, on the father’s side and his great grandson on her side; a pure-blooded, royal prince of the Argead royal house of Macedon. Never again would it be possible for someone such as Perdikkas – a man of distant royal blood – to seek to marry Kleopatra and make himself king through her weak, female inheritance. Her son with her idiot of a husband would have the strongest claim to being Alexander’s heir; stronger even than his own son and namesake through that eastern wild-cat, her deadly rival, Roxanna, for she was from far-off Bactria and no Macedonian blood flowed through her veins. The younger Alexander would have to wait at least ten years before he could sire a child, and a lot could happen to a person in ten years. And Roxanna will be only too aware of that fact. Adea looked over to her husband, thirty-eight years old but with the mind of an eight-year-old, sitting in the corner playing with a carved wooden elephant, trumpeting and drooling in equal measure as his personal physician, Tychon, watched over with a look of indulgence on his lined face. Roxanna will redouble her efforts to poison Philip now that Perdikkas is not around to keep her in check, if only I knew what he had on her that she feared him so. Adea swiped the whetstone along the blade she honed, enjoying the metallic rasp of sharpening iron. I wish Mother was still with me, she would know how to keep that man-child safe as her mother had kept her safe from Olympias in her turn. Her idiot husband had been made imbecilic as a child by Alexander’s mother, Olympias, attempting to remove another rival wife; the dose she had given her pregnant victim had been insufficient to kill the child she bore, but it had done a decent-enough job.

But Cynnane, her mother, was dead and Adea, at seventeen, had to fend for herself in a man’s world. Her mother, however, had brought Adea up in the ancient way of Illyrian princesses for Cynnane had been sired by Philip of Macedon on Audata, a princess of Illyrian Dardania, given in marriage to seal a treaty. Audata had taught Cynnane the art of the blade, in all its forms, and, in turn, Cynnane had passed this knowledge on to Adea. It was with her skill at weapons and her size – as tall and broad as a man and with muscles to match – that Cynnane had hoped Adea would survive when she had sought to marry her to Philip and make a bid for empire. But Cynnane had been killed by Perdikkas’ younger brother, Alketas, as he attempted to turn the two women back before they reached Babylon.

Such was the outcry from Alexander’s veterans that a half-sister of his should be murdered in cold blood that Perdikkas had been forced to allow the marriage to go ahead against his wishes. Thus Adea became a queen and thus she had earnt the everlasting enmity of the deadly Roxanna, so free with her potions.

But what good was a blade against the poisoner’s draught? Roxanna had already managed to poison Philip once but had been coerced into administering the antidote by Perdikkas; who would have that power over the eastern bitch now?

It was with heavy heart and dragging legs that Adea set down her blade, walked over to her husband, took his hand and led him to her bed, screened off from the rest of the tent. Tychon followed and together they undressed Philip who panted with excitement for he knew what treat was in store for him and being the possessor of a prodigious penis took great pleasure in wielding it. Removing Philip’s loincloth, Adea massaged the organ to ensure its readiness as Tychon held his charge, restraining him in the way that he and Adea had evolved over the months to make the act safe for her, as Philip knew not his strength, nor had he empathy with his partner. Indeed, two unfortunate slaves had bled to death in his early years.

Once satisfied that all was ready, Adea turned around and knelt upon the bed, buttocks raised; she pulled up her tunic and, nodding to Tychon, grabbed the pillow and closed her eyes. As Philip thrust into her without preamble, she turned her mind to the man she assumed would be the new regent, Ptolemy, and whether he would be able to protect her. Egypt, she considered, as her husband pounded away under the watchful eye of Tychon, could suit her well.

‘Although I am deeply flattered,’ Ptolemy declaimed with the risen sun glowing golden in the east before him, ‘deeply flattered, my brothers, I am not the right man to assume the regency and take on the guardianship of the two kings. We propose that Peithon and Arrhidaeus should jointly take up the role until the meeting at The Three Paradises can decide a long-term solution.’

Adea’s hands involuntarily gripped the arms of her chair and she cast a fleeting, sidelong look at Ptolemy; he was standing at the front of the dais with the senior officers around him, before the whole army, parading in rigid units, throwing long shadows. Her husband sat next to her, a fixed and vacant grin on his face as Ptolemy invited the two temporary regents to step forward and commended the choice to the army. Beyond Philip sat Roxanna with the infant king on her lap; heavily kohled, cold eyes flashing from the narrow slit in her veil, chilling Adea with the depth of their loathing as she glanced at her and then Philip. She thinks that now is her chance, Peithon and Arrhidaeus mean nothing to her. Instinctively, she reached over and took Philip’s hand and heard Roxanna hiss at the sight; she felt her Illyrian bodyguard, Barzid, move closer to her in reaction to Roxanna’s naked hatred. Antipatros will be our best hope now.

‘…and to help heal the wounds caused by Perdikkas’ foolish declaration of war against me,’ Ptolemy continued as the infant king burst into a wail; his mother’s long fingernails had dug into his arms, so consumed was she with loathing for his co-monarch next to her, ‘I have had the bodies of your dead comrades retrieved from the river and individually cremated with honour; as soon as the bones are cooled they will be collected and sent to you, their messmates, for you to deal with as you wish.’

The cheers this announcement brought briefly drowned the child’s cries; buoyed by the good feeling emanating from his audience, Ptolemy let them laud him with his arms open, embracing them all.

Adea almost felt pity for the infant as Roxanna thrust the mewling brute into the arms of the waiting nurse who acted far more maternally towards him than did his mother; indeed, she knew from a spy in the household that Roxanna only ever held Alexander when she appeared with him before the army assembly. But Adea was not the only person to observe the scene: from within the crowd of officers surrounding Ptolemy, Kassandros’ pale eyes hardened as he watched the exchange before his gaze caught hers; he inclined his head, his expression chill, and she knew that in him she had yet another who, if he did not actively wish her harm, was not her friend. With his eldest son against me, how can I appeal to Antipatros for protection? Still, judging by the way Kassandros looked at them, he is no friend of Roxanna and her whelp either; evidently of the same mind as Perdikkas. A man to watch and to avoid.

Signalling for silence, Ptolemy began to wind up his oration. ‘Finally, Brothers, I have to be the bearer of bad tidings; news of the worst degree.’ He paused as if he were trying to find the words to express the depth of the tragedy. ‘It’s no use, Brothers; I cannot sweeten the blow so I shall just say it how it is: Krateros is dead.’

A few moments’ stunned silence and then a howl of grief erupted from the army; it rose and rose as the enormity of what had occurred sunk in. Krateros, the greatest general after Alexander himself, was dead; the darling of the army, never defeated, beloved for his prowess and his willingness to share in the hardships of his men, always eating whatever fare they had to make do with, and respected for his conservative views on the diluting of the Macedonian army with easterners: a soldiers’ soldier; one whom they had known for most of their military lives.

It was with genuine surprise that Adea saw tears flooding down grizzled faces; men hardened by years of campaigning seemed to be brought low to snuffling wrecks as if they had just discovered their entire families raped with their throats cut and the loot of many years of campaigning gone.

Two veterans, well into their sixties, climbed onto the dais, tears drenching their beards. ‘Tell us how this happened,’ one shouted at Ptolemy over the grief.

‘It will give me no pleasure, Karanos.’ Raising his hands into the air, Ptolemy sought to quieten the assembly and soon the mourning was limited to stifled sobs. ‘Eumenes, Perdikkas’ supporter, refused to see sense and surrender to Antipatros and Krateros; in the ensuing battle he treacherously withheld the fact from his own Macedonians that it was Krateros whom they faced. Our great friend died at the hands of Eumenes’ barbarian cavalry.’

This was too much for men who had spent the last years crushing every barbarian standing in their path; they howled for Eumenes’ death and then for the deaths of Alketas, Perdikkas’ brother, and Attalus, his brother-in-law, as well as Polemon and Docimus, his two leading supporters, recently fled from the camp. Again, Ptolemy begged for silence. ‘It is the right of the full army assembly to pass judgement upon individuals deemed to be guilty of crimes against army. Is it your wish to pass sentence on Eumenes for his part in the death of Krateros and on Alketas, Attalus, Docimus and Polemon for their support of Perdikkas?’

The answer was unambiguous.

‘Death to all his supporters and family,’ the second veteran demanded.

‘Is this what you wish too, Karanos?’

‘It is.’

The cry was soon taken up by the entire army and its will was immovable.

Ptolemy turned to the officers standing behind him on the dais and none made to object. ‘So be it,’ he shouted, ‘a sentence of death is hereby passed upon Eumenes, Alketas, Attalus, Docimus, Polemon and all Perdikkas’ supporters and family; anyone who has the opportunity to execute any one of them may do so. Failure to carry out that duty—’

But a woman’s screams cut him short; Adea searched the crowd for their source. With clothes torn and hair awry, a woman was being dragged towards the dais. The men parted for her, hurling abuse as they did but offering her no physical violence. Closer she was hauled, and Adea could detect a look of regret passing over Ptolemy’s face for he too had recognised who she was and what the men would demand of him for she was Perdikkas’ sister, Attalus’ wife, Atalante.

‘Ptolemy! Ptolemy!’ Atalante shrieked, writhing in the grip of many hands. ‘Ptolemy, demand that they release me.’ In her mid-thirties, she possessed, still, beauty and confidence, but neither of these were now on display; nor was the hauteur which she had always shown Adea during the few dinners that they had shared around Perdikkas’ table; Adea felt the change suited her. She still resented Atalante for defying her by saving her brother, Alketas, from the justice of the mob for the killing of Cynnane, her mother. The gods laugh at me one moment and smile upon me the next.

Screaming another appeal to Ptolemy, Atalante fell to her knees, panic in her eyes as the realisation of who she was spread through the men closest to her and they crowded towards her. ‘Ptolemy, save me!’

But Ptolemy could do naught but shake his head in regret.

Adea could understand Ptolemy’s predicament. The sentence has been passed on Perdikkas’ family, men and women alike; he’s caught. He can do nothing for fear it will seem like weakness in him.

But it was as Atalante’s garments were ripped, exposing her breasts that Ptolemy could no longer be a by-stander. ‘Hold!’ he roared as Seleukos pushed through the officers on the dais to stand next to him. ‘You will not dishonour her.’ He jumped down into the crowd, with Seleukos close behind, and pulled her dress together to cover her modesty. ‘No matter that she is Perdikkas’ sister, you will not dishonour her.’

Atalante embraced Ptolemy’s legs. ‘Thank you, thank you.’

Ptolemy reached down and eased away her grip. ‘Don’t thank me, Atalante, I can’t save you, the sentence is passed; but I can ensure that it is carried out cleanly and that your honour remains intact.’

Dark eyes, clouded with misery, stared up at him and a thin wail grew and then died in her throat.

I would take no pleasure in her suffering at the hands of the men, but her death is something that I’ll not regret; not after she affected to look down on me, a queen, and she being nothing but the sister of the regent – the late regent. But it serves as a warning as to just how quickly our fortunes can change in such volatile times and just where the real power lies: it’s the army that has its way now, not the generals. That is my way forward.

Between them, Seleukos and Ptolemy cleared an area around the condemned woman as the entire army cried for her blood. Adea saw Ptolemy share a questioning look with Seleukos and then shrug his shoulders as a thought occurred to him as if he suddenly saw a positive side to the situation.

Atalante caught the meaning of the gesture and it seemed to steady her for she rose to her feet and held her head high and her shoulders back. ‘Very well, if I am to be executed for the deeds of my brother then let it be done with dignity so that you can all witness how a high-born Macedonian woman can die.’ She turned to Ptolemy and pulled open her dress. ‘If you say you cannot save me then it shall be you who should carry out the sentence.’ She lifted her left breast and pointed to her heart. ‘Strike here and strike hard.’

Ptolemy’s normally relaxed demeanour slipped for a few moments as he contemplated her exposed chest. He drew his sword. ‘Hold her shoulders firm, Seleukos, so that she doesn’t flinch and I miss the mark.’

Atalante pushed Seleukos away. ‘I’ll not flinch, Ptolemy, but you’re more than welcome to have him steady your arm should your nerves at killing a woman in cold blood cause it to shake.’

Ptolemy smiled, his composure returning. ‘I’ll not miss.’

It was with a flash of burnished iron in the growing sun, the dull thud of a blade striking flesh and bone and the shocked exhalation of Atalante’s breath that Ptolemy drove his sword, up, under her ribcage, deep, through her heart to jag to a halt on the inside of her shoulder blade. Blood oozed from quivering lips and her eyes widened; she looked down at the wound as if to fully comprehend the reality of it. Putting a hand on Ptolemy’s shoulder, she let her legs give and, in stages, down she went. Seleukos placed a hand under her arm and eased her descent so that there should be no final slump. She came to her knees, rested a hand on the ground and then, with Seleukos’ and Ptolemy’s help, lay down on her side, drawing her legs up, blood now flowing free from the wound as well as her mouth and nose. In the foetal position she looked up to Ptolemy, the light now dimming within her. ‘I did nothing wrong.’ Her mouth slackened; her body went limp.

If I ever share her misfortune I hope that I will face it in such a manner. But one look at her husband showed that he had not taken the same lesson from Atalante’s execution, far from it judging by his obvious excitement. Disgusted with the man and yet feeling a strange urge to protect him at the same time, Adea took his hand and led him from the dais as Ptolemy pulled the sword from Atalante’s breast.

‘The sentence has been passed at the army assembly,’ she heard Ptolemy shout as she descended the wooden steps, ‘and once it is passed only the army can rescind it. It gave me no pleasure to execute a woman, but it is done now and through this act we have passed the point of no return; there can be no understanding now between us and Perdikkas’ followers. They will not be coming to The Three Paradises to make a final settlement with Antipatros; it is now to the death. All of them, especially Eumenes.’

Adea smiled to herself as she led her husband away, holding his wrist firmly to prevent him playing with himself, her confidence growing for she had seen her way forward. I may not have many friends at the moment but I would hazard that, soon, after talking to Karanos, I’ll have a few more than Eumenes. And then, despite Kassandros, Antipatros will have to deal favourably with me.

ANTIPATROS.THE REGENT.

‘AND WHERE’S NICAEA?’ Antipatros asked his eldest son, having been apprised of the news from the south; the information had made him far more well-disposed towards Kassandros than would normally be the case and he smiled at him in a manner that could almost be construed as natural and easy. They sat, along with Nicanor, Kassandros’ younger full brother, and his half-brother, Iollas, under an awning looking out over the sea, on the beach at Issos, the site of Alexander’s stunning victory in which Darius, the King of Kings of the Persian empire, had been utterly defeated and forced to flee deep inland. The sun hung low in the west and around them the army of Macedon prepared the evening meal, filling the atmosphere with the smell of grilled seafood and thousands of voices.

‘Still in Babylon, Father, where I left her,’ Kassandros replied, tearing at the loaf of bread before the slave had even placed it on the table.

‘Then at least she is safe for the time being.’

‘Safe enough, yes; but technically she was condemned to death along with the rest of Perdikkas’ friends and family.’

‘I don’t think they’ll worry about her until they find Alketas, Attalus, Docimus and Polemon,’ Nicanor observed. Younger than his sibling by three years, he lacked the same wiry, lanky frame, the pinched features and surly manner and was far more pleasing to both the eye and the ear.

‘As soon as they heard what had happened to Perdikkas they knew they would be condemned; Alketas, Docimus and Polemon slipped away, but no one knows where to, and Attalus withdrew his fleet from the Nile delta and sailed to Tyros.’

‘Tyros?’ Antipatros groaned. ‘Of course he would, there are eight thousand talents in the royal treasury there; that will buy a lot of men for his ships and equip Alketas with an army if they join together. Alexander took two years to take Tyros. I don’t suppose anyone will be able to do it quicker without the help of treachery; the Perdikkans are a long way from being totally defeated even though they’ve lost their leader.’

‘And then there’s Eumenes,’ Nicanor said, equally downcast, looking nervously at his father as he brought up what he knew to be a very painful subject. ‘He may have been condemned by the army assembly but he’s still controlling Kappadokia and Phrygia since he defeated Krateros.’

‘And he makes me look a fool! But I’ll have him, the sly little Greek, and regain my honour. Whatever happens, I’ll see him dead. I’ll try sending Archias the Exile-Hunter after him, but it’s one thing assassinating unprotected exiles, it’s quite another trying to kill a general in the midst of his army. Still, he’s the best there is at his trade.’ Antipatros contemplated the humiliation inflicted on him by Eumenes for a few moments and then shook his head in disbelief. ‘Just how did a secretary defeat and kill a general as experienced as Krateros?’

‘You shouldn’t have divided your forces, Father,’ Kassandros said, almost flinching in anticipation of a sharp rebuke.

Antipatros glared at his son but said nothing. Unfortunately he’s right, with the benefit of hindsight. But now is the time for looking forward, not back. ‘How long did it take you to get here?’

‘Three days; Ptolemy lent me a ship. I was just behind Attalus’ fleet as it sailed into Tyros.’

Antipatros beamed, feeling more optimistic at the news. ‘Ptolemy helped you? The good lad; he’s proving to be a compliant son-in-law. He’ll ingratiate himself even more with me by returning Alexander’s body; what he wants with it in Egypt I just don’t understand.’

Kassandros shook his head. ‘It would be a useless demand, Father; best not to make it and avoid looking weak when he refuses you. Alexander stays in Egypt whether Ptolemy’s your son-in-law or not; he sees the possession of it as a way of establishing his legitimacy. He has no need to ingratiate himself with anyone; he was just being civil in lending me that ship as a brother-in-law should be.’

Antipatros felt his warmth towards his son-in-law diminish. ‘Then we had better send it back to him with a strong letter reminding him that we are family and need to work together for our common good, hadn’t we?’

‘The ship’s already gone; but not back, on.’

‘On? Where to?’

‘I didn’t ask the triarchos,’ Kassandros replied through another mouthful of bread. ‘It came as a surprise to me; he literally dropped me off and then, as soon as I was on dry land, left.’

‘On, eh?’ Antipatros’ good feeling towards Ptolemy evaporated entirely. This is so tiresome; I’m getting far too old for these games. ‘The conniving bastard must be sending a message to Kleopatra in Sardis. He knows that she will write at once to warn Eumenes. Ptolemy is, as usual, playing both sides and I’ll wager that the ship will carry on to Macedon and deposit a messenger heading for that witch, Olympias, in Epirus. I’ll have a quiet but firm word with him at The Three Paradises.’

‘I’m afraid you won’t, Father, he’s not coming.’

This was too much for Antipatros. ‘Not coming! Not coming to the most important conference since Alexander died? Why ever not?’

‘He doesn’t see the need to talk about the rest of the empire when he is perfectly happy in Egypt and has no wish to leave. He told me he would be content with whatever settlement we came up with so long as it left him alone; he added that he wouldn’t want things to become unpleasant.’

‘Unpleasant! I’ll give the ungrateful bastard unpleasant! How am I meant to organise a lasting peace if we don’t have everyone who matters around the table; even Lysimachus is coming, for Aries’ sake, and he’s got no interests outside Europe at all, being quite content to spend his time subduing the northern Thracian tribes. Ptolemy has to come!’ Antipatros rubbed his forehead with a wrinkled and blotchy-skinned hand, feeling every one of his eighty years. That’s just it: he doesn’t have to come. To all intents and purposes, Egypt is an island and if Ptolemy wants to stay there then there is nothing that I can do about it. Gods, how I wish Hyperia were here; I’m in dire need of the comforts of a wife. Controlling himself, he looked back to Kassandros and Nicanor and then to Iollas, his third eldest son, leaning against one of the awning’s poles. ‘So, Perdikkas is dead, boys, and Eumenes and his other supporters have a price on their head which I’m very sure that the Exile-Hunter will be only too pleased to claim. Where does that leave us?’

‘On top, Father,’ Kassandros replied without pause for thought.

‘Think before you answer,’ Antipatros snapped, his mood towards his eldest now fragile. ‘If the two temporary regents decide that they would rather be permanent, then who are we to force them to stand down without the threat of violence; the very thing that I’ve called The Three Paradises conference to put an end to? But persuade them we must, for if I want to bring stability to the empire, and avoid further conflict, then it’s imperative that I have the two kings back in Macedon where they belong. To do that I must be not only the regent of Macedon but of them as well, in order to prevent Olympias using the young Alexander as her route back to power.’ He looked down at the skin on the backs of his hands. ‘There are few enough years remaining to me and I want them to be as peaceful as possible. I’ve had my share of struggle and now I wish to enjoy some rest; that will not be possible if I have to contend with Olympias scheming to get hold of her grandson and trying to murder the fool.’