6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

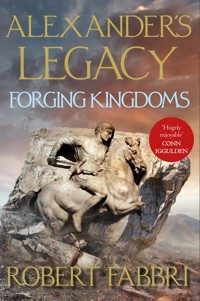

'An excellent new series by the consistently brilliant Robert Fabbri' Sunday Sport _____________________________ Let the battles begin... 'I foresee great struggles at my funeral games.' Babylon, 323 BC: Alexander the Great is dead, leaving behind him the largest, and most fearsome, empire the world has ever seen. As his final breaths fade in a room of seven bodyguards, Alexander refuses to name a successor. But without a natural heir, who will take the reins? As the news of the king's sudden and unexpected death ripples across the land, leaving all in disbelief, the ruthless battle for the throne begins. What follows is a devious, tangled web of scheming and plotting, with alliances quickly made and easily broken, each rival with their own agenda. But who will emerge victorious: the half-chosen; the one-eyed; the wildcat; the general; the bastard; the regent? In the end, only one man, or indeed woman, will be left standing...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

Robert Fabbri read Drama and Theatre at London University and worked in film and TV for twenty-five years. He has a life-long passion for ancient history, which inspired him to write the bestselling Vespasian series and the Alexander’s Legacy series. He lives in London and Berlin.

Also by Robert Fabbri

THE VESPASIAN SERIES

TRIBUNE OF ROME

ROME’S EXECUTIONER

FALSE GOD OF ROME

ROME’S FALLEN EAGLE

MASTERS OF ROME

ROME’S LOST SON

THE FURIES OF ROME

ROME’S SACRED FLAME

EMPEROR OF ROME

MAGNUS AND THE CROSSROADS BROTHERHOOD

THE CROSSROADS BROTHERHOOD

THE RACING FACTIONS

THE DREAMS OF MORPHEUS

THE ALEXANDRIAN EMBASSY

THE IMPERIAL TRIUMPH

THE SUCCESSION

Also

ARMINIUS: LIMITS OF EMPIRE

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Robert Fabbri, 2020

Map and illustrations © Anja Müller

The moral right of Robert Fabbri to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 796 3

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 797 0

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 799 4

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

To my agent, Ian Drury, with whom I share apassion for this period of history.

A list of characters can be found on page 412.

PROLOGUE

BABYLON, SUMMER 323 BC

‘TO THE STRONGEST.’ The Great Ring of Macedon wavered in Alexander’s dimming vision; his hand shook with the effort of raising it and then speaking. Emblazoned with the sixteen-pointed sun-blazon, the ring represented the power of life and death over the largest empire ever conquered in the known world; an empire that he must bequeath so early, too early, because he, Alexander, the third of that name to be King of Macedon, knew now that it was manifest: he was dying.

Rage surged within him at capricious gods who gave so much and yet exacted so high a toll. To die with his ambition half-sated was an injustice that soured his achievements, augmenting the bitter taste of death that rose in his gorge; for it was but the east that had fallen under his dominion; the west was yet to witness his glory. And yet, had he not been warned? Had not the god Amun cautioned him against hubris when he had consulted the deity’s oracle in the oasis of Siwa, far out in the Egyptian desert, nigh on ten years ago? Was this then his chastisement for ignoring the god’s words and reaching further than any mortal had previously dared? Had he had the energy, Alexander would have wept for himself and for the glory that was slipping through his fingers.

Without an obvious, natural heir, who would he allow to follow him? To whom would he give the chance to rise to such heights as he had already attained? The love of his life, Hephaestion, the only person he had treated as an equal, both upon the field of battle and within the bed they shared, had been snatched from him less than a year previously; only Hephaestion, beautiful and proud Hephaestion, would have been worthy to expand what he, Alexander, had already created. But Hephaestion was no more.

Alexander held the ring towards the man standing to the right of his bed, closest to him, the most senior of his seven bodyguards surrounding him, all anxious to know his will in these final moments. All remained still, listening, in the vaulted chamber, decorated with glazed tiles of deep blue, crimson and gold, in the great palace of Nebuchadnezzar at the heart of Babylon; here in the gloom of a few weak oil-lamps, for little light seeped through the high windows from the early-evening, overcast sky, they waited to learn their fate.

Perdikkas, the commander of the Companion Cavalry, so far loyal to the Argead royal house of Macedon but ambitious in his own right and ruthless with it, took the symbol of ultimate authority from his king’s forefinger; he asked his question a second time, his voice tense: ‘To whom do you pass your ring, Alexander?’ He glanced around his companions before looking back down at his dying king and adding: ‘Is it to me?’

Alexander made no attempt to reply as he looked around the semi-circle of the men closest to him, all formidable military commanders capable of independent action and all with the human lust for power: Leonnatus, tall and vain, modelling his long blonde hair in the same style as his king, aping his looks, but whose devotion was such that he had used his own body to shield Alexander when he fell wounded in far-off India. Peucestas, next to him, already was showing signs of going native in his dress, having been the only bodyguard to have learnt Persian. Lysimachus, the most reckless of them all, was possessed of bravery that was often a hazard to his own comrades. Peithon, dour but steadfast; unquestioning in his execution of even the most cruel orders, when others might quail. And then there were the older two: Aristonous, who had been Alexander’s father, Philip, the second of that name’s, bodyguard; the only survivor of the old regime, whose counsel was infused with the wisdom of one old in the ways of war. And finally, Ptolemy; what to make of Ptolemy whose looks hinted at him being a bastard brother? At once gentle and forgiving and yet capable of ruthless political adroitness should that part of his nature be abused; the least competent militarily but the most likely to succeed in the political long game.

Alexander looked past the seven, as Perdikkas repeated the question a third time, to the men beyond the bed; men who had followed him, sharing the dangers and the triumphs, on his ten-year journey of conquest, silent in the shadows as they strained to hear him answer. Passing along the dozen or so faces he knew so well, his weak gaze rested on Kassandros standing next to his younger half-brother, Iollas, and Alexander thought he detected triumph in his eyes; his sickness had started the day after Kassandros’ arrival from Macedon as his father, Antipatros’ messenger; had Antipatros, the man who had ruled as regent in the motherland for the past ten years, sent his eldest son with the woman’s weapon of poison to murder him rather than obey the summons that Alexander had sent? Iollas was, after all, his cup-bearer and could easily have administered the dose. Alexander cursed Kassandros inwardly, having always hated the ginger-haired, pock-marked prig whose loathing had been returned in equal measure and augmented by his humiliation at having been left behind for all those years. His mind turned back to Antipatros, a thousand miles away in Pella, the capital of Macedon, and his constant feud with his, Alexander’s, mother, Olympias, scheming and brooding back in her native Molossia, a part of the kingdom of Epirus; how would that resolve without him playing off one against the other? Who would kill whom?

But then, half obscured by a column at the far end of the dying-chamber, Alexander glimpsed a woman, a pregnant woman; his Bactrian wife, Roxanna, three months from full term. What chance would a half-caste child have? Not many shared his dream of uniting the peoples of east and west; there would be few Macedonians of pure blood who would rally behind a half-breed infant born to an Eastern wildcat.

So it was with certainty, as he closed his eyes, that Alexander foresaw the struggles that would mark his passing, both in Macedon and here in Babylon and then throughout the subject Greek states, as well as among those of his satraps who had carved out fiefdoms of their own in the vast empire he had wrought; men such as Antigonos, The One-Eyed, satrap of Phrygia and Menander, satrap of Lydia, the last of Philip’s generals.

Then there was Harpalus, his treasurer, whom he had already forgiven once for his dishonesty, who, rather than face Alexander’s wrath a second time, had absconded with eight hundred talents of gold and silver, enough to raise a formidable army or live in luxury for the rest of his life; which would he choose?

And what would Krateros do? Krateros, the darling of the army, a general second to only Alexander himself, now somewhere between Babylon and Macedon, leading ten thousand veterans home; would he feel that he should have been named Alexander’s successor? But Alexander, weakness creeping through him, had made his decision and, as Perdikkas once more put the question, he shook his head; why should he give away what he had won? Why should he give the chance to another to equal or surpass him? Why should not he, alone for ever, be known as ‘The Great’? No, he would not do it; he was not going to name the Strongest; he was not going to give them any help.

Let them work it out for themselves.

Opening his eyes one last time, he looked up at the ceiling, his breathing fading.

All seven around the bed leant in, hoping to hear their name.

Alexander twitched one last smile. ‘I foresee great struggles at my funeral games.’ He gave a sigh; then the eyes, that had seen more wonders than any before in this world, closed.

And they saw no more.

PERDIKKAS,THE HALF-CHOSEN

THE RING FELT heavy in his hand as Perdikkas’ fingers closed about it; it was not for the gold of which it was wrought but for the power in which it was steeped. He looked down at the still face of Alexander, as beautiful in death as it had been in life, and felt his world teeter so that he had to steady himself with his other hand on the oaken bedhead, alive with ancient animalistic carvings.

He drew breath and then looked to his companions, the six other bodyguards sworn to the death to the king who was no more; on the countenance of each was evidence of the gravity of the moment: tears on the faces of Leonnatus and Peucestas, each heaving their chest with irregular sobs; Ptolemy, rigid, eyes closed as if deep in thought; Lysimachus clenched and unclenched the muscles of his jaw, his hands in white-knuckled fists; Aristonous struggled for breath and then, forgetting dignity, squatted down on the floor with one hand supporting him. Peithon stared at Alexander, his eyes wide, dead to emotion.

Perdikkas opened his hand and gazed at the ring. Now was his time – should he dare to claim it as his own; Alexander had chosen him to receive it after all. And he chose well, for of all here in this room I am the most worthy; I am his true heir. He picked it up and held it between thumb and forefinger, examining it: so small, so mighty. Can I claim it? Would the others let me do so? The answer came quick, as unwelcome as it was unsurprising. In the second group, beyond the bed, his younger brother, Alketas, standing between Eumenes, the sly little Greek secretary, and the grizzled veteran, Meleagros, caught his eye and slowly shook his head; he had read Perdikkas’ mind. In fact, all in the room had read his mind as all eyes were now upon him.

‘He gave it to me,’ Perdikkas affirmed, his voice imbued with the authority of the symbol he held before him. ‘It was I whom he chose.’

Aristonous got to his feet, his voice weary. ‘But he did not name you, Perdikkas, although I would that he had.’

‘Nevertheless, I hold the ring.’

Ptolemy half-smiled, bemused, shrugging his shoulders. ‘It’s such a shame, but he half-chose you; and a half-chosen king is just half a king. Where’s the other half?’

‘Whether he chose anyone or not,’ a voice, gravelled by the shouting of battlefield commands, boomed, ‘it is for the army-assembly to decide who is Macedon’s king; it has ever been thus.’ Meleagros strode forward, his hand on his sword-hilt; his beard, full and grey, dominated his weathered face. ‘It is for free Macedonians to decide who sits on the throne of Macedon; and it is the right of free Macedonians to see the body of the dead king.’

Two dark eyes stared at Perdikkas, daring him to defy ancient custom; eyes that were full of resentment, as he knew only too well, for Meleagros was almost twice his age and yet remained an infantry commander; Alexander had passed him over for promotion. However, it was not through ineptitude that he had failed to rise, it was because of his qualities as a leader of a phalanx. It took much skill to command the sixteen-man-wide-and-deep Macedonian phalanx unit; it took even more to command two score of these two-hundred-and-fiftysix-man speira in conjunction, and Meleagros was the best – with the possible exception of Antigonos One-Eye, Perdikkas allowed. To ensure the right pace as the unit manoeuvred over various terrains so that every man, wielding his sixteen-feetlong sarissa, pike, was able to keep formation could not be learnt in one campaigning season. The phalanx’s strength was its ability to deliver five pikes for every one-man frontage; armies had broken on it since its introduction by Alexander’s father, but only because of men like Meleagros knowing how to keep it ordered so that the front five ranks could bring their weapons to bear whilst the rear ranks used theirs to disrupt missiles raining down upon them. Meleagros kept his men safe and they loved him for it and they were many. Meleagros could not be dismissed.

Perdikkas knew that he was beaten, for the moment at least; to realise his ambition he needed the army, both infantry and cavalry, on his side and Meleagros spoke for the infantry. Gods, how I hate the infantry and I hate this bastard for blocking my way – for now. He smiled. ‘You are, of course, right, Meleagros; we stand here debating amongst ourselves as to what we should do and we forget our duty to our men. We should muster the army and give them the news. Alexander’s body should be removed to the throne-room so that the men can file past it and pay their respects. On that, at least, do we all agree?’ He looked around the room and saw no dissent. ‘Good. Meleagros, you call the infantry and I’ll summon the cavalry; I’ll also send out messengers to every satrapy with the news. And let’s always remember we are brothers with Alexander.’ He paused to let that sink it, nodded at them and then made for the door, wanting only some time to himself to reflect upon his position.

But it was not to be; as a dozen conversations broke out around the corpse of Alexander, echoing around the cavernous chamber, Perdikkas felt someone fall into step beside him.

‘You need my help,’ Eumenes said, without looking up at him, as they walked through the door and into the main central corridor of the palace.

Perdikkas looked down at the little Greek, a whole head shorter than him, and wondered what it had been that made Alexander give him the military command left vacant when he, Perdikkas, had replaced Hephaestion; there had been much disquiet when Alexander had rewarded Eumenes’ years of service, firstly as Philip’s secretary before transferring his allegiance to Alexander upon his assassination, by making him the first non-Macedonian commander of Companion Cavalry. ‘What could you possibly do?’

‘I was brought up to be polite to someone offering a service; in Kardia it is considered good manners. But, I grant you, we do differ in many ways from Macedon: for a start, we’ve always enjoyed eating our sheep.’

‘And we’ve always enjoyed killing Greeks.’

‘Not as much as the Greeks do themselves. But be that as it may, you do need my help.’

Perdikkas did not reply at first as they marched, now at speed, along the corridor, high and broad, musty with age, the geometrical paintwork fading and peeling in the humid atmosphere that afflicted Babylon. ‘Alright; you’ve made me curious.’

‘A noble condition, curiosity; it’s only through curiosity that we can reach certainty as it causes us to explore a topic from all angles.’

‘Yes, yes, very wise, I’m sure, but—’

‘But you’re just a blunt soldier and have no use for wisdom?’

‘You know, Eumenes, one of the reasons that people dislike you so intensely is—’

‘Because I keep on finishing their sentences for them?’

‘Yes!’

‘And there was me thinking that it was only because I’m an oily Greek. Oh well, I suppose one can’t help but learn as one gets older, unless, of course, one is Peithon.’ A sly glint came into his eye as he looked up at Perdikkas. ‘Or Arrhidaeus.’

Perdikkas waved a dismissive hand. ‘Arrhidaeus has never learnt a thing in his thirty years other than to try not to drool out of both sides of his mouth at the same time. He probably doesn’t even know who his own father is.’

‘He may not know he’s Philip’s son but we all do; as does the army.’

Perdikkas halted and turned to the Greek. ‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘You see, I told you that you needed my help. You said it yourself, he’s Philip’s son which makes him Alexander’s half-brother and, as such, his legitimate heir.’

‘But he’s a halfwit.’

‘So? The only other two direct heirs are Heracles, Barsine’s four-year-old bastard, or whatever is lurking in that eastern bitch Roxanna’s belly. Now, Perdikkas, where will the army stand when presented with that choice?’

Perdikkas grunted and turned away. ‘No one would choose a halfwit.’

‘If you believe that then you’re automatically ruling yourself out.’

‘Piss off, you Greek runt, and leave me alone; you can make yourself useful by mustering your cavalry.’

But as Perdikkas walked away he was quite certain that he heard Eumenes mutter: ‘You really do need my help and you will get it, like it or not.’

ANTIGONOS,THE ONE-EYED

GODS, how I hate the cavalry. Antigonos, the Macedonian governor of Phrygia, muttered a series of profanities under his breath as he watched the lance-armed, shieldless, heavy-cavalry on his left wing attempt to form up on rough ground, far further from the left flank of his phalanx than he had ordered. The error left too much space for his peltasts to cover once they had finished driving off the skirmishers from the scrubland protecting the enemy’s opposite flank; it also pushed his javelin-armed, mercenary Thracian light-horse too far away for them to be able to respond with alacrity to any signal he might send. However, he hoped to finish the day’s work with one mighty blow from his twelve-thousand-eight-hundred-strong phalanx. All his adult life Antigonos had been an infantry commander, leading his men from the front rank, looking no different to them, wielding a sarissa whilst shouting orders to the signaller six ranks behind; at fifty-nine he was still taking joy in the power of the war-machine that his old friend, King Philip, had introduced. And, as such, he knew the value of cavalry to protect the cumbersome flanks of the phalanx from enemy horse; but that was why he disliked them so much as they were constantly boasting that the infantry would be dead without them. Annoyingly, that was the truth.

‘Go up there,’ Antigonos bellowed at a young, mounted aide, ‘and tell that idiot son of mine that when I say fifty paces I don’t mean a hundred and fifty. I may only have one eye but it is not totally useless. And tell him to hurry up; there’s no more than an hour of daylight left.’ He scratched at his grey beard, grown full and long, and then took a bite from the onion that passed for his dinner. Despite his youth, his son, Demetrios, showed promise, Antigonos conceded, even if he did favour the cavalry as it far better suited his flamboyant behaviour; he just wished that he would take more heed of orders and reflect more upon the implications of doing as he pleased. A lesson in discipline was what the boy needed, Antigonos reflected, but he was constantly thwarted by his wife, Stratonice, who doted on him to the extent that he could do no wrong in her eyes; it was to drag Demetrios away from her skirts that he had brought his fifteen-year-old son on his first campaign and given him command of his companion cavalry.

Chewing, Antigonos examined the rest of his disposition from his command post on a knoll behind the centre of his army. He swallowed and then washed down the mouthful with strong, resonated wine; emitting a loud burp, he handed the wineskin to a waiting slave and took a deep breath of warm, late-afternoon air. He liked this country with its ragged hills and fast-flowing rivers; rock and scrub, hard land, land that reminded him of his home in the Macedonian uplands; land that chiselled a man rather than moulding him with gentle hands. But however good the land might be for the forming of a man’s character, it was a liability to the conduct of smooth military operations. And it was with both those considerations in mind that he studied the Kappadokian satrap’s army facing him, formed up with a river, a hundred paces wide, spanned by a three-arched stone bridge to its rear. He scanned the ranks of brightly robed clansmen, whose colours were enhanced by the sinking sun, clustered around a centre of a couple of thousand Persian regular infantry, in front of the bridge, stringing their bows behind their propped-up wicker pavises. In embroidered trousers and long bright-orange and deep-blue tunics and sporting dark-yellow tiaras, they were the original satrapy garrison that had helped Ariarathes, Darius’ appointment, to hold out against Macedonian conquest for the ten years since Alexander, after a brief foray as far as Gordion, bypassed central Anatolia, taking his army south by the coastal route.

But now Antigonos had cornered this warlord of the interior who had preyed upon his supply lines and left a trail of his men writhing on stakes throughout the country; or at least cornered his army for he had no doubt that whatever the result of the coming conflict, Ariarathes would escape. It was a shame after the effort of having force-marched from Ancyra along the King’s Road, the mighty construction that linked the great cities of the Persian Empire with the Middle Sea. The speed of his move had caught Ariarathes’ army as it attempted to cross the narrow bridge over the River Halys back into Kappadokia after their latest raid. Caught in a bottleneck, Ariarathes had no choice but to turn and fight as he tried to extract as many of his troops as possible from the precarious position; only the setting of the sun could save him. As he watched, Antigonos saw many scores of the rebels streaming over the bridge and he had no doubt in his mind that Ariarathes would have been the first across. But I’ll trim his wings today, whether he survives or not. He looked behind towards the westering sun. Provided I do it now and quickly. A glance up to his left told him that Demetrios had finally formed up in the correct position; satisfied that all was in order, Antigonos stuffed the rest of the onion into his mouth, jogged down the knoll and then, rubbing his hands together and chuckling in anticipation of a good fight, made his way through the phalanx to his position in the front rank.

‘Thank you, Philotas,’ he said, taking his sarissa from a man of similar age. ‘Time to drown as many of these rats as possible,’ he added with a grin. Taking his round shield that had been slung over his shoulder, he threaded his left hand through the sling so that he could grip his pike with both hands and still rely on a degree of protection from the shield even though he could not wield it as a hoplite would his larger hoplon. Without looking behind, he shouted back to the horn-blower. ‘Phalanx to advance, attack pace.’

Three long notes sounded and were repeated all along the half-mile frontage of the phalanx. As the last call rang out in the distance the first horn-blower took a deep breath and blew a long shrill note. Almost as one, the men of the front ranks stepped forward to be followed by the file behind them; with rank after rank rolling forward, giving a ripple effect like breakers surging to the shore, the army of Antigonos closed with the foe.

It was with the same pride that he always felt when advancing at the heart of a phalanx that Antigonos tramped forward, his great pike held upright so that he could keep his shield covering as much of his body as possible as they neared the enemy. Gods, I could never tire of this. He had fought in the phalanx ever since its inception, firstly in Philip’s wars against the city state of Byzantion and the Thracian tribes to secure his eastern and northern borders; there the tribesmen had skewered themselves on the hedge of iron that protruded from the formation so that very few managed to close into the individualistic hand to hand combat they favoured. But it was in Greece that the new, deeper formation had really been tested; Philip gradually expanded his power south until it was to Macedon that the Greek cities deferred and the days when Macedonians were publicly derided as being no more than barely civilized provincials of questionable Hellenic blood were gone – those thoughts were now shared only in private. The heavier phalanx had crushed the hoplite formations and the lance-armed Macedonian cavalry swept their javelin-wielding opponents from the field. Antigonos had loved every moment, never happier than when he was in the heart of a battle.

However, he had been left behind by Alexander soon after he had crossed into Asia and defeated the first army that Darius had sent against him at Gaugamela; but it had not been a dishonourable dismissal: Alexander had chosen Antigonos to be his satrap in Phrygia precisely because of his joy of war. The young king had trusted him to conclude the siege of the Phrygia’s capital, Celaenae, and then to complete the conquest of the interior of Anatolia whilst he went south and east to steal an empire. Ariarathes was the last Persian satrap to still resist in Anatolia and Antigonos thanked the gods for him for without him he would have nothing more to do other than collect taxes and hear appeals; in fact, sometimes he wondered to himself whether he had allowed Ariarathes to hold out on purpose just so that he would always have a good excuse to go campaigning. But now that news had reached him that Alexander had returned out of the east and had recently arrived in Babylon, Antigonos had decided that a very real attempt should be made to rid this part of the empire of the last rebel satrap; he did not want to face the young king, for the first time in almost ten years, without completing the task he had been entrusted with.

With the thunder of twelve thousand footsteps crunching down on hard ground in unison, the phalanx pressed on and Antigonos’ heart was full. To his left he could make out the peltasts, named after their crescent, hide-covered-wicker pelte shields, drive the archers threatening that flank from the scrubland in which they had taken cover; blood had been spilt and life was good. With a final volley of javelins, aimed at the backs of the retreating skirmishers, the peltasts rallied and withdrew to their position between the phalanx and the covering cavalry that advanced, as ordered, at the same pace as the infantry. Gods, I do so love this. Antigonos’ beard twitched as he smiled behind it; his one good eye gleamed with excitement and the puckered scar in his left socket, which gave him a fearsome countenance, wept bloody tears. One hundred paces to go; gods this will be good.

Looking out from behind their pavises, the Persian infantry aimed their bows high; a cloud of two thousand arrows rose into the sky and Antigonos’ smile grew broader. ‘Keep it steady, lads!’ And down the arrows plunged, clattering through the swaying forest of upright pikes; their momentum broken, they did little harm; here and there a scream followed by a series of curses as the casualty’s comrades stepped over the fallen man and struggled to avoid getting their feet caught on his discarded pike. Some gaps would open, Antigonos knew, but they would soon be filled as the file-closers pushed men forward; he did not need to look round to make sure that was happening.

Again, another shower of iron-tipped rain fell from the sky and again it was mostly soaked up by the canopy over the phalanx’s heads, the missiles falling to the ground as if twigs broken off in a tempest. Fifty paces, now. ‘Pikes!’ Another signal blared out and was repeated along the line, but this time the manoeuvre did not need to be completed in unison; from the centre, spreading left and right, pikes came down as a wave, the front five ranks to horizontal and the rear ranks to an angle over the heads of the men in front, shielding them still from the continuing arrow-storm.

Hunching forwards, Antigonos counted his steady, even paces, impatient for each one, as the enemy neared; now the Persian aim was more direct and arrows began to slam into the front rank’s shields that rocked with the impacts as they were not held secure with a fist gripping a handle but just slung loose over the arm. Now the casualties began to mount; unprotected faces and thighs became targets; screams of pain became commonplace as, with the wet thuds of a butcher’s shop, iron-tipped missiles pierced flesh and came to a juddering halt on bone. Shaft after shaft hissed in and Antigonos smiled still; he had not been touched since one had taken his eye at Chaeronea when Philip had defeated the combined forces of Athens and Thebes. Since then he had been blessed of Ares, the god of war, and felt no fear walking into a blizzard of arrows. Now he could see the Persians’ eyes as they aimed their shafts. An instinct made him duck his head; an arrow clanged off his bronze helmet, making his ears ring; he raised his face and laughed at the enemy, for they were going to die.

Taking up their pavises to use as more conventional shields, the Persians jammed their bows back into the cases on their hips, pulled long-thrusting spears from the ground and stood shoulder to shoulder, dark eyes staring at the oncoming phalanx, bristling with life-taking iron-points. Antigonos’ laugh turned into a roar as he trudged the final few steps, the muscles in his arms aching with the strain of holding the pike level. His men roared with him, natural fear flowing from them to be replaced by the joy of combat.

And then he was there and now he could kill; with a power that filled him with joy, Antigonos thrust the pike forward at the hennaed-bearded face of the Persian before him, each man in the front rank judging the timing of the killing blow for himself; the Persian spun away from the pike-tip and grabbed the haft, attempting to yank it from Antigonos’ grasp, but he pushed on, along with the rest of his men, forcing their way forward, so that within two paces the second rank sarissas were coming in under those in front of them at belly height. On they pushed, pace by pace, working their weapons, still well out of reach of the enemy who now struggled, as the third rank’s points came into range, with the multitude of weapon-heads ranged against them.

A couple of Persians, braver than the rest, charged forward, their spears over their shoulders, twisting between the wooden hafts, making for Antigonos, whose pike point was now lost to view; but still he kept stabbing forward, blind, as the Persians approached to within range of their weapons. But Antigonos did not flinch for he knew the men behind him; out of the corner of his eye he saw a pike being raised as the fourth-ranker lifted his arms and thrust his weapon forward. With a scream, a Persian doubled over the wound in his groin, fists pulling at the pike embedded in it as another comrade behind Antigonos, with a sharp jab, dealt with the second man. And still they moved forward, the pressure mounting with every step, but the weight of the phalanx was what made it so difficult to stand against and all along the line the enemy floundered as their frontage buckled. It was the Kappadokian clansmen, to either side of the Persians, tough men from the mountainous interior, who turned first; unable to face the Macedonian war-machine with only javelins and swords they ran, in their thousands, towards the river for they knew that a Macedonian phalanx could not chase its quarry with any speed.

With pride Antigonos looked to his left and saw exactly what he had hoped to: his son, purple-edged white cloak billowing behind him, leading the charge, at the head of the wedge formation so favoured by the Macedonian Companion Cavalry, which would achieve what the phalanx could not. And it was with speed and fury that they swept into the broken Kappadokian ranks, the wedge increasing pressure the deeper it drove, crashing men aside and trampling many more beneath thrashing hoofs as lances stabbed at the backs of the routed, dealing out wounds of dishonour. It was then that the right flank cavalry hit, boxing the beaten army in; the Persians now knew they could not possibly hope to extricate themselves across the bridge to safety and they too turned in flight.

Antigonos raised a fist in the air; a horn rang out once more. The phalanx had done its work and would halt, resting, whilst it watched the glory-boys of the cavalry do the easy part of the action: murder the vulnerable.

All were driven before them as the heavy-cavalry swept through from both flanks. Further out, light-cavalry patrolled in swirling circles, picking off the few fortunate enough to escape; Antigonos had indicated before the action that he had no interest in prisoners unless it be Ariarathes himself as he had a particularly wide stake ready for the rebel to perch on. Only the enemy cavalry managed to escape with their mounts swimming to the far bank.

With the phalanx precluding any flight to the west, those who could not get on to the bridge, now heaving with a stampede of the desperate, had but one choice to make: certain death on the point of a cavalry lance or the river. And so the Halys churned with drowning men, each trying to survive at the expense of others as the current washed them away, sucking them under. Some, those with the luck of their gods on their side, managed to cling to one of the two great stone supports sunk into the riverbed, although many were hauled off by others grabbing at their ankles as they swept past. A few managed the climb up to the parapet but none made it over into the crush of humanity swarming across but were, rather, thrust back down into the river by men who saw that another person on the bridge would lessen their own chances of survival.

Antigonos laughed as he watched Demetrios and his comrades spear fleeing Persian infantrymen as they attempted to push their way onto the bridge. Their Boitian-style helmets, painted white with a golden wreath etched around them, glowed warm in the rays of the setting sun as, sitting well back on their mounts and gripping with their thighs, their feet hanging free, they controlled their beasts with a deftness born of a life in the saddle. Calf-length leather boots, a boiled-leather or bronze muscled-cuirass with fringed leather pteruges beneath it, protecting the groin, and tunics and cloaks of differing hues, red, white, dun or brown, they made for a fine sight Antigonos was forced to concede. And, as they slaughtered their way through to the crush attempting the bridge, few turned to oppose them for most had discarded their weapons as they fled.

Antigonos slapped Philotas on the shoulder as Demetrios’ lance broke and he reversed it to use the butt-spike. ‘The boy’s enjoying himself; he seems to be getting a taste for Easterners’ blood. And it’s about time: Alexander was roughly the same age when he led troops in battle for the first time.’

Philotas grinned as Demetrios’ flanker took a Persian’s hand off as he attempted to drag the young lad from the saddle. ‘Caunus is looking after him, so he shouldn’t come to any harm. You’ll just have to stress to him that it isn’t always quite so easy.’

‘He’ll learn that soon enough.’

Demetrios’ unit, an ile of one hundred and twenty-eight men, was now at the bridge, the leading six hacking and stabbing their way forward as the press of the vanquished thinned out and flight became swifter; and still they killed and still men fled before them. On they drove and the smile faded from Antigonos’ face the further they went. The little fool. He turned to the signaller. ‘Sound the recall!’

The horn blared rising notes that were repeated throughout the formation yet Demetrios led his men on until there were none left on the bridge to kill and he burst out onto the eastern bank and, in the last of the light, slew all he could find.

‘If a Kappadokian doesn’t kill him,’ Antigonos muttered, ‘then I will when he gets back.’

‘No you won’t, old friend; you’ll cuff him round the ears and then give him a hug for being a fool, but a brave one.’

‘My arse I will; it’s foolish behaviour like that that gets people killed unnecessarily. He’s either got to learn discipline or resign himself to a short life.’

‘In my experience it’s not always the foolish that suffer as a result of their actions.’

Antigonos’ face darkened. ‘If my son ever does that again, Philotas, I pray to Ares that you’re right and he doesn’t kill himself.’

ROXANNA, THE WILD-CAT

THE CHILD KICKED within her. Roxanna put both hands to her belly; she sat, veiled, in the open window of her suite on the second floor of the palace in Babylon. Below her, in the immense central courtyard of the complex, now ablaze with torches as the sun sank from the overcast sky, the Macedonian army gathered for yet another meeting.

It was just one more strange thing that she had never been able to fathom about the way the Macedonian mind worked: why did they allow all their citizens to have a say? Before Alexander had defeated her father, Oxyartes – and then appointed him satrap of Paropamisadae – his will in her native Bactria was questioned on pain of impalement and yet, Alexander, a man who, she had to admit, had been far more powerful than her father could ever hope to be, actually listened to the opinions of the common soldiery. Indeed, it had been a near mutiny that had forced him to turn back from India. She shook her head at the lawlessness of a system whereby consensus ruled and swore that the boy-child she carried would not have such a handicap inflicted upon him when he came to the throne.

And that thought turned her mind back to her main preoccupation during Alexander’s illness which had now become a burning issue since his death but two hours previously: how to ensure the boy would come to rule, for she knew that her life depended upon it.

Again the child gave a mighty kick and Roxanna cursed her late husband for abandoning her just at the time she needed him most. Just when she was going to triumph and produce an heir before his other two wives, the Persian bitches whom Alexander had married in the massed wedding at Susa when he had forced all his officers to take Persian spouses; just as she was on the point of becoming the most important person in Alexander’s life now that her main rival, Hephaestion, was no more.

She turned and clicked her fingers at the three slave-girls waiting on their knees with their heads bowed, just as Roxanna liked it, in the far corner of the room. One girl got to her feet and padded, head still bowed, over the array of carpets of varying hues and designs of the type favoured in the east; she stopped close enough to her mistress so that Roxanna would not be forced to raise her voice, for that required energy and Roxanna believed that a queen should not be expected to expend her energy unnecessarily; it should be preserved for her king.

Roxanna ignored the girl, turning her attention back to the events unfolding below; horns were sounding and the fifteen-thousand-strong Macedonian citizens present in the army of Babylon, now formed up in their units, became silent as seven men mounted the podium in the centre of the courtyard.

‘Which one?’ Roxanna muttered to herself, under her breath, scrutinising Alexander’s bodyguards. ‘Who will it be?’ She knew them all, some better than others, for she had vied with them all since her marriage three years ago, at the age of fifteen, as she had struggled to maintain her position in such a masculine society that was the army of Alexander.

It was Perdikkas, dressed in full uniform – helm, cuirass, leather apron, greaves and a cloak of deepest red – who stepped forward to address the assembly. Roxanna had thought it would be as she had seen him take the ring from Alexander but still cursed her luck: Leonnatus would have been far more malleable, his vanity made him so; Peucestas, the lover of pleasure and fine things, would have easily slipped into her bed or, indeed, Aristonous, to whom she could have appealed to his strong sense of duty to the Argead royal dynasty of Macedon. But Perdikkas? How would she bend him to her will?

‘Soldiers of Macedon,’ Perdikkas declaimed, his voice high and carrying over the vast, shadowed host; the bronze of his helmet glistering in the torchlight as the light breeze fluttered its red horse-hair plume. ‘I expect you have all heard of the tragedy that has befallen us for bad news is fleeter than good. Alexander, the third of his name, the Lion of Macedon, is dead. And we, his soldiers, will mourn him in the Macedonian manner. The campaign in Arabia is, therefore, postponed so that funeral games with rich prizes may be held over the next few days. But first we shall do what is right and proper: we shall, each and every one of us, pay our last respects to our king; his body has been moved to the throne-room. We will file past in our units. The cavalry shall go first. Once all have been witness to his death, then, and only then, will we have an assembly to appoint a new king, two days hence.’

As Perdikkas continued addressing the army, Roxanna snapped at her slave waiting behind her. ‘Fetch Orestes, I have a letter to write.’

The secretary arrived within a few moments of the girl leaving the room, as if he had been awaiting her summons; perhaps he had been, Roxanna reflected, he had been most attentive since she had caused the little finger of his left hand clipped off for keeping her waiting too long after being called for. Alexander had chided her for inflicting such a punishment on a freeborn Greek and told her to make recompense but she had laughed at him and said that a queen should never be kept waiting and, besides, she had done it now and no amount of recompense would re-grow it. Alexander, fool that he was, had compensated the man from his own purse. ‘To Perdikkas,’ she said without turning around to see if the man was ready. ‘From Queen Roxanna of Macedon, greetings.’ She heard the stylus begin to scratch as she formulated the next line in her head, never once taking her eye off her quarry who was still addressing the troops below. ‘I require your presence to discuss the regency and other topics of mutual benefit.’

‘That is all, majesty?’ Orestes asked as his stylus stilled.

‘Of course it’s all! Had there been more I would have said it! Now get out and write a fair copy and then bring it to me so I can have one of my maids deliver it.’ Roxanna smiled to herself as she listened to Orestes hurriedly gather his things and scamper from the room. Greeks, how I loathe them; especially those who can write. Who knows what secrets and spells they conceal? Down in the courtyard Perdikkas had finished speaking and Ptolemy had taken the podium to declaim his grief. She wondered whether lots had been drawn but she rather thought not; what she was witnessing was the order of precedence that the bodyguards had sorted out amongst themselves.

By the time she had despatched her letter, Peucestas was the last to speak, following Lysimachus, Leonnatus and Aristonous – Peithon, being a man of few words, each preferably with few syllables, had not attempted to. As the assembly broke up and the great file-by had begun, Roxanna ordered a jug of sweet wine and commanded her maids to redo her hair and makeup as she awaited her guest.

Her coiffure could have been reworked thrice by the time Perdikkas was announced by her steward.

‘You kept me waiting,’ Roxanna said, her voice low, as the tall Macedonian strode into her chamber. She removed her veil and stared at him with almond eyes, giving a hint of a flutter of the eyelashes.

‘You’re lucky that I had the time to come at all; there have been messengers to send out and much to organise,’ Perdikkas replied, sitting without asking leave or commenting on her naked face. ‘Are you going to cut one of my fingers off as a warning against tardiness? Next time I suggest you come and find me.’

Roxanna’s eyes flashed with anger; she waved her slaves out of the room. ‘I’m your queen; I can summon you any time I wish.’

Perdikkas stared at her levelly, contemplating her with his sea-grey eyes; she did not relish it but held his gaze. Clean-shaven, like many close to Alexander, his face was lean with high cheekbones and a slender nose and close-clipped black hair; a pleasing face, she allowed, one that she would not mind being in close contact with, should the need arise. She glanced at his hands; he was not wearing the ring.

‘You are not my queen, Roxanna,’ Perdikkas said after a few moments, ‘nor have you ever been. To me, and the rest of the army, you are nothing but a barbarian savage whom Alexander brought back from the east as a trophy. And you would do well to remember that in the coming days.’

‘How dare you speak to me like that? I—’

‘You are now no more than a vessel, Roxanna,’ Perdikkas cut across her with force, pointing at her pregnancy, ‘a useful vessel, granted, but a vessel nonetheless. What you carry within you has value, you do not. The only question is: how much value does it possess? Not much if it turns out to be female.’

Roxanna put a hand on her belly and clenched her jaw. ‘He is a boy-child,’ she hissed through her teeth, ‘I know it.’

‘How can you be certain?’

‘A woman knows; he sits low within me and he kicks with all his strength.’

Perdikkas dismissed her assertion with a wave of his hand. ‘Believe what you want; we will all know one way or the other in three months. Until then I would advise you to keep out of sight so the men aren’t constantly reminded of the fact that Alexander’s heir is a half-breed.’

‘They love me.’

Perdikkas sighed and shook his head; the harshness came out of his voice. ‘In the last year of his life, Alexander began training easterners in the Macedonian fashion, making phalangites out of them. When he sent Krateros home with ten thousand veterans he did not replace them with Macedonians but, rather, these new pseudo-Macedonians, and the men don’t like it. If your child is a boy we will have a struggle to have him accepted by all Macedonians.’

‘Which is why I summoned you.’

Perdikkas gave an exasperated look. ‘Roxanna, I will not play games with you; I hold Alexander’s ring, I am summoned by nobody. I came because I would rather talk to you here where there is a certain degree of privacy. Now, what did you want to say to me?’

Roxanna, realising that trying to assert her rightful position would just aggravate Perdikkas more, decided against forcing her claim to superiority. ‘You need me, Perdikkas.’ She was taken aback by his sudden outbreak of mirth. ‘You laugh at me? Why?’

‘You are the second person to have told me that this evening.’

‘Who was the first?’

‘You don’t need to know that.’

I do, I do very much need to know who else is vying for his attention. ‘I’m sure that he can’t be nearly as useful as I can be.’

‘I’m not sure that he could.’

Good, it’s not a woman. ‘You hold the ring, and your six colleagues in the Bodyguard have evidently deferred to you as it was you who addressed the army first this evening. Now, let us be practical: you would like to rule in Alexander’s place but the others won’t accept that, if they did you would be wearing that ring now, but you’re not. I can offer you the regency of my son until he comes of age in fourteen years.’

‘I could just take the regency; I have no need to receive it from your hand.’

Roxanna smiled; it was, she knew, her finest feature, which was why she bestowed it rarely, thereby adding to its effect. ‘To be an effective regent you have to be ruling over a united realm and all your subjects must accept you as the regent. If I endorse you then that could well happen. But just imagine if I make that proposal to Leonnatus, for example; can there be two regents? I rather think not. And do you think that Leonnatus would turn down the chance of that power knowing what he thinks of himself? And who do you think Ptolemy would support if it were a choice between you and Leonnatus?’

‘You wouldn’t.’

The smile faded and her eyes hardened. ‘I would, what’s more, you know I could.’

Perdikkas considered the situation.

I think I have him.

‘What do you want,’ Perdikkas said eventually.

I do have him, now I just need to teach him some manners. ‘Stability for my son; there can be only one true-born heir.’

‘You want Heracles dead?’

‘Heracles? No, that bastard is not a threat to me. Alexander never acknowledged Barsine so he has no precedence over my son. It’s the two bitches in Susa.’

‘Stateira and Parysatis? They can’t threaten your position.’

‘They’re pregnant, both of them.’

‘Impossible; Alexander hasn’t seen them since Hephaestion’s funeral cortège passed through Susa nine months ago. If he impregnated them then we would all know by now.’

‘Even so, I want them dead and I want you to kill them for me.’

‘Kill women? I don’t do that; especially as the women concerned are Alexander’s wives.’

‘Send someone to do it then or I go to Leonnatus.’

‘Do you really think Leonnatus would stoop to murdering women, knowing what he thinks of himself?’ It was Perdikkas’ turn to smile. ‘Or any of the bodyguards, for that matter.’

Roxanna cursed the man inwardly and then tried a different tack. ‘Shouldn’t Alexander’s wives all be in Babylon to mourn him? Surely Stateira and Parysatis would welcome the chance to weep by his body?’

Perdikkas gave a grim smile as he grasped the meaning of what Roxanna was saying. ‘I will be responsible for their safety once they are here.’

‘But not whilst they are on the road, how could you be?’

Again he looked at her long and hard and, from his eyes, Roxanna knew that she would triumph.

Perdikkas stood. ‘Very well, Roxanna, I will summon Stateira and Parysatis to Babylon and you will endorse me as regent. If it becomes appropriate, I shall inform the senior officers of the army of your decision when we meet the day after tomorrow before the army assembly.’

‘You may indeed do that,’ Roxanna said with much grace whilst bestowing another rare smile. She watched him turn and leave the room, the smile fixed to her face. So, Stateira and Parysatis, you will soon learn what happens to my rivals; just as did Hephaestion.

PTOLEMY, THE BASTARD

CLEVER, VERY CLEVER, Ptolemy thought as he looked at the layout of the throne-room in which he and his colleagues were gathering, two days after Alexander’s death. He hated to admit it, but, however much he disliked the man, Perdikkas had been clever; but Ptolemy had always found that enmity did not need to preclude admiration.

At the far end of the hall the final few infantry units of the army of Babylon continued to file past the body of their king, lying dressed in his richest uniform: a purple cloak and tunic, a gilded breastplate inlaid with gemstones and engraved with gods, horses and the sixteen-point sun-blazon of Macedon and knee-length boots of supple calfskin; his parade helmet rested in the crook of his right arm. But it was not calling the meeting in full view of the last part of the army paying its respects to Alexander that impressed Ptolemy, it was what Perdikkas had made of the other end of the room: the great carved-stone throne of Nebuchadnezzar was draped with Alexander’s robes, his favoured hardened-leather battle-cuirass, inlaid with a leaping horse on each pectoral, was placed, along with his ceremonial sword, at its base; but the master-stroke in Ptolemy’s eyes was his diadem resting on the seat with The Great Ring of Macedon laying within it.

He’s set up the meeting to be as if it is in the very presence of Alexander, Ptolemy thought, looking around the gathered senior officers: the six other bodyguards plus Alketas, Meleagros, Eumenes and the tall, burly Seleukos who was now the Taxiarch, the commander, of the Hypaspists, one of the two elite infantry units of the army; he had made his name, three years previously, commanding the newly formed elephant squadron. How many of them will support Perdikkas? Ptolemy mused as he studied each face. Eumenes certainly because, as a Greek, he needs a Macedonian sponsor to stand any chance of reward. His attention was drawn by an older man entering the room, weather-beaten with eyes like slits from years of squinting into the sun. Nearchos, interesting; he has the same problem as Eumenes, but our formidable Cretan admiral will be a boon to whoever he chooses to support; it’s a shame I have nothing to tempt him with.

It was no surprise to Ptolemy that Kassandros was the last to arrive. Now he will need watching; how such an arrogant piece of vixen vomit was sired by Antipatros, I’ll never know. Still, I hear the old man’s latest batch of daughters have matured nicely. Kassandros as a brother-in-law? Now there’s a thought. And indeed it was, for it set Ptolemy’s mind working; no route to the life of wealth, leisure and power that he so craved after years of enduring the rigours of campaign should be left unexplored. And that was what Ptolemy was determined to reward himself with, seeing as no one else would; being reputedly the bastard son of King Philip, he had always been treated with subtle contempt. Only Alexander had accorded him respect, making him one of his bodyguards to the ill-concealed surprise of those better born. Having lived his life under the taint of bastardy, his happiness was his alone to grasp and he meant to have a firm grip on it over the coming months.

With the final arrival, Perdikkas called the meeting to order; all were dressed as if for battle to stress the urgency of the situation. I’d best be on my guard as whatever is decided here will be with Alexander’s blessing and I wouldn’t wish another to get my prize.

‘Brothers,’ Perdikkas began as they stood in the shadow of the ghost seated on the throne above them, ‘I’ve called you here to decide upon a common proposal that we can put to the army assembly.’

A proposal that you hope will grant you full power whether as regent or king, Ptolemy mused whilst nodding his head with much solemnity as if Perdikkas’ purpose was altruistic and for the common good rather than, as he suspected, self-serving. I saw your eyes when Alexander gave you the ring.

‘As we all know, Alexander’s first wife, Roxanna, is close to full term; if the child is a boy then we shall have a legitimate heir. I propose that we should wait to see the outcome of the birth.’

It was what was left unsaid that interested Ptolemy the most: who would rule until then? Well, that’s obvious.

‘Why wait when there is already a living heir?’ The voice came from the fringe of the gathering. Nearchos, the Cretan admiral, stepped forward. ‘Heracles is four years old, the regency would therefore be only ten years rather than fourteen.’

‘Greek!’ Peithon thundered. ‘Macedon first!’

‘You’re speaking out of turn, my friend,’ Eumenes said, wagging a finger at Nearchos. ‘We must defer to our betters for our blood is but the thin Greek sort, not the strong, thick stuff that surges in Peithon’s veins. But with patience I’m sure you’ll get the chance to promote the interests of your bastard half-brother-in-law.’

Very good, Eumenes, Ptolemy thought as Nearchos was forced to step back to the fringes with the Macedonians shouting down his protests, that’s got rid of that. As a mark of esteem, Alexander had given to Nearchos Barsine’s eldest daughter, only twelve at the time, at the Susa weddings, making him Heracles’ brother-in-law, and no doubt he fancied himself as his young relation’s regent despite his Cretan blood.