Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

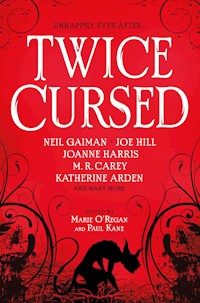

From the fun of the fair to the depths of hell, experience sixteen more curses in this sequel to the bestselling Cursed: An Anthology. A blend of traditional and reimagined curses from fairy-tales to Snow White, from some of the best names in fantasy. BE CAREFUL WHAT YOU WISH FOR Take a trip to a terrifying carnival and uncover the secrets within, solve a mysterious puzzle box and await your reward, join a travelling circus and witness the strangest ventriloquist act you've ever seen. In this follow-up to the bestselling Cursed: An Anthology, you'll unearth curses old and new. From a very different take on Snow White, to a new interpretation of The Red Shoes, the best in fantasy spin straw into gold, and invite you into the labyrinth. Just don't forget to leave your trail of breadcrumbs… Featuring stories from: Joanne Harris Neil Gaiman Joe Hill Sarah Pinborough Angela Slatter M. R. Carey Christina Henry A. C. Wise Laura Purcell Katherine Arden Adam L. G. Nevill Mark Chadbourn Helen Grant Kelley Armstrong A. K. Benedict L. L. McKinney

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 439

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Introduction

BY MARIE O’REGAN & PAUL KANE

The Bell

JOANNE HARRIS

Snow, Glass, Apples

NEIL GAIMAN

The Tissot Family Circus

ANGELA SLATTER

Mr Thirteen

M. R. CAREY

The Confessor’s Tale

SARAH PINBOROUGH

The Old Stories Hide Secrets Deep Inside Them

MARK CHADBOURN

Awake

LAURA PURCELL

Pretty Maids All In A Row

CHRISTINA HENRY

The Viral Voyage of Bird Man

KATHERINE ARDEN

The Angels of London

ADAM L. G. NEVILL

A Curse is a Curse

HELEN GRANT

Dark Carousel

JOE HILL

Shoes as Red as Blood

A. C. WISE

Just Your Standard Haunted Doll Drama

KELLEY ARMSTRONG

St Diabolo’s Travelling Music Hall

A. K. BENEDICT

The Music Box

L. L. MCKINNEY

About the Authors

About the Editors

Acknowledgements

TWICECURSED

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

A Universe of Wishes: A We Need Diverse Books Anthology

Cursed: An Anthology

Dark Cities: All-New Masterpieces of Urban Terror

Dark Detectives: An Anthology of Supernatural Mysteries

Dead Letters: An Anthology of the Undelivered, the Missing, the Returned…

Dead Man’s Hand: An Anthology of the Weird West

Escape Pod: The Science Fiction Anthology

Exit Wounds

Hex Life

Infinite Stars

Infinite Stars: Dark Frontiers

Invisible Blood

Daggers Drawn

New Fears: New Horror Stories by Masters of the Genre

New Fears 2: Brand New Horror Stories by Masters of the Macabre

Out of the Ruins: The Apocalyptic Anthology

Phantoms: Haunting Tales from the Masters of the Genre

Rogues

Vampires Never Get Old

Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands 2: More Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands: The New Apocalypse

Wonderland: An Anthology

When Things Get Dark

Isolation: The Horror Anthology

Multiverses: An Anthology of Alternate Realities

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

TWICE CURSED

Paperback edition ISBN: 9781803361215

Electronic edition ISBN: 9781803361222

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

First edition: April 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Introduction © Marie O’Regan & Paul Kane 2023.

The Bell © Frogspawn Ltd 2023.

Snow, Glass, Apples © Neil Gaiman 1994. Originally released by

Dreamhaven Press as a benefit book for the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

Reprinted by permission of the author.

The Tissot Family Circus © Angela Slatter 2023.

Mr Thirteen © M. R. Carey 2023.

The Confessor’s Tale © Sarah Pinborough 2009. Originally published inHellbound Hearts, edited by Paul Kane & Marie O’Regan (Pocket Books, 2009).Reprinted by permission of the author. Clive Barker is the owner of the copyright of theHellbound Heart and Cenobite mythology, and Sarah Pinborough gratefully acknowledgesMr Barker’s permission to draw on this mythology for “The Confessor’s Tale”.

The Old Stories Hide Secrets Deep Inside Them © Mark Chadbourn 2023.

Awake © Laura Purcell 2023.

Pretty Maids All In A Row © Tina Raffaele 2023.

The Viral Voyage Of Bird Man © Katherine Arden 2023.

The Angels Of London © Adam L. G. Nevill 2013. Originally published inTerror Tales of London, edited by Paul Finch (P&C Finch Ltd, 2013).

Reprinted by permission of the author.

A Curse Is A Curse © Helen Grant 2023.

Dark Carousel © Joe Hill 2018. Originally published as a vinyl original(HarperAudio 2018). Reprinted by permission of the author.

Shoes As Red As Blood © A. C. Wise 2023.

Just Your Standard Haunted Doll Drama © Kelley Armstrong 2023.

St Diablo’s Travelling Music Hall © A. K. Benedict 2023.

The Music Box © L. L. McKinney 2023.

The authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

TWICECURSED

INTRODUCTION

BY MARIE O’REGAN & PAUL KANE

Cursed…

We were certainly beginning to think things were, when our first anthology with that name came out. In fact, the signing for that book at Forbidden Planet in London, back in March 2020, was the last live event we attended for more than two years because of the pandemic. Very shortly after that, the UK went into its first lockdown. The huge convention we’d been working on for three years by that point had to be postponed with only a few weeks to go (StokerConUKTM, which subsequently became the highly successful ChillerCon UK), we were all in lockdown and the world suddenly seemed a very strange, often frightening place. At the time of writing it still does to some extent. It’s definitely a different world to the one we knew when we penned our introduction to the original Cursed.

Nevertheless, here we are again with Twice Cursed. Some might say we’re tempting fate, especially given other recent events globally. However, as we all found during these unprecedented and trying times, fiction – films, TV and books especially – proved a welcome distraction from real life. It’s kept us going ourselves, honestly – has kept most people going, as indeed it did in other challenging periods of history. Fiction in whatever form serves an important function, and reading about curses, of one sort or another, is definitely preferable to being traumatised in your everyday life. Cursed, but in a good way – there’s safety in keeping these curses contained within a book’s pages. The reader, at least, can get out.

Therefore, we’re proud to present another batch of excellent fables from a group of superb writers at the top of their game. Each one of them with a different variation on what curses are, and what they mean to us as individuals or as a collective.

Joanne Harris reminds us of the true nature of curses, while Neil Gaiman and Laura Purcell tackle Snow White from very different perspectives. A. C. Wise introduces us to some cursed footwear, Mark Chadbourn is in archaeological territory and Sarah Pinborough’s Hellish Faustian Pact shows us the power of keeping secrets. And while Kelley Armstrong gives us her own unique twist on the old favourite of cursed dolls, Christina Henry takes a look at the subject from the opposite perspective, and Katherine Arden uses a well-known bad luck legend as her inspiration. Angela Slatter, Joe Hill, and A. K. Benedict all deal with curses connected to entertainment – at a circus, on a pier and in music hall – and Adam L. G. Nevill’s tale is also rooted in a sense of place, this time a strange lodging house. M. R. Carey focuses on the people you should turn to if you need support when you have a curse, L. L. McKinney presents us with a very unique music box, and Helen Grant’s story is a cautionary piece that resonates in our present day.

All very different, all excellent. All a thoroughly enjoyable break from the realities around us. So settle back, with a glass or mug of your favourite tipple, and enter a world of magic. Of trickery and despair.

Curses again… Twice Cursed, but in a good way.

MARIE O’REGAN & PAUL KANEDerbyshire, July 2022

THE BELL

BY JOANNE HARRIS

In a village by the edge of a forest, there lived a woodcutter’s family. They were poor; they lived from the land, and the land was far from generous. They ate black bread, and roots, and seeds, and small fish from the river. But they were free, and happy – except perhaps for the woodcutter’s son, who longed for something different.

In all his life, the woodcutter’s son had never drunk wine, or eaten bread that was not black and unleavened. In all his life he had never worn clothes that had not been first worn by someone else. And he was always listening to tales of ancient Kings and Queens – their wealth, their adventures, their glamour – and longing for the old days, when things were very different.

He often asked his father where those ancient Kings and Queens had gone, and how their kingdoms had fallen.

But his father would always tell him: “That was long before my time. No-one remembers the old days now.”

The boy was disappointed, but he did not forget the tales of knights and ladies, Kings and Queens. He would often roam the forest alone, searching for signs of the old days.

Sometimes he even found them – pieces of masonry sunk in the ground, scattered fragments of coloured glass. A gilded comb, a strand of hair still caught between its ivory teeth.

Then one day, in the heart of the woods, he came across a city, ruined and abandoned in the scrambling undergrowth. Great pillars of marble and arches of stone were draped in morning glories. And under an intricate vaulted dome, through which a curtain of ivy fell, he found a great gathering of stone, a feasting-hall of statues.

The boy walked through the hall of stone. On either side, lords and ladies, some holding goblets to their lips, some laughing, some dancing; some hiding their smiles behind their painted ivory fans. On the tables between them, platters of fruit and cakes were spread out, all in stone, and perfect, even to the water-droplets on the bunches of grapes. Above them, a minstrels’ gallery, its music silenced, except for the drip of water from the ceiling. At either side of the room, stone guards in their helmets and armour. And at the head of the great hall, the King and Queen of the city sat on thrones of polished marble; and to the boy they looked both wise, and very, very beautiful.

“What happened here?” he said aloud.

A voice spoke up behind him. It was that of a ragged old crone, hiding among the statues.

“I remember all this,” she said. “I was a servant in this place. Oh, it was beautiful in its time, a place of joy and music. But it fell under a spell – a curse – and its people were all turned into stone.”

The boy’s eyes widened. He could already imagine himself a member of that gilded throng. He saw himself dancing with beautiful girls, and eating all kinds of sweetmeats. His father would wear furs, he thought: his sisters, gowns of silken brocade.

“If only the curse could be broken,” he said.

“Oh, but it can,” the old crone replied, her dark eyes gleaming like gemstones. “All it needs is for one brave boy to ring that big old bell up there.”

And she pointed to a great brass bell, hanging from the ceiling in a mass of vines and spiders’ webs.

“And that will bring them back?” said the boy.

The old crone nodded. “A single note would be enough to awaken them.”

The boy looked up, and started to climb. It was a difficult, dangerous task. But finally, he reached the bell, and pulled its clapper free, and it rang. The brass note shimmered in the air like a cloud of fireflies.

And slowly, below him, the courtiers of stone began to awaken; began to move. The beautiful ladies shifted and yawned; the guards stood to attention. Laughter rang once more through the hall that had been silent for hundreds of years.

But somehow, the joyful scene was not quite the way the boy had imagined it. There was something about the laughter that came from the throats of the courtiers: a cruel and acquisitive look in the eyes of the ladies.

The boy clambered down from the ceiling and waited for someone to notice him.

Surely, my reward will come, he thought, looking at the magnificent feast, and imagining all the things he would buy with the gold they would give him.

But instead of showing their gratitude, the beautiful King and Queen just spread their wings and watched the boy with hungry eyes. The courtiers and their ladies, too, crowded round the frightened boy, licking their lips and smiling. The music from the gallery began to play – an evil tune, that made his head spin and sent his pulses racing.

The boy grew pale and turned to run. But there was nowhere to run to. And the Queen put her thin white hand on his neck and drew him closer, smiling.

When they had finished with the boy, the King and Queen and their courtiers and guards took wing and flew over the land like locusts. They enslaved the people, slaughtered their flocks, burnt down their homes and their settlements. For centuries, the enchantment had kept them tame and helpless. Now, at last, they were awake, and they had no mercy.

Back in the deserted hall, the old crone shrugged her shoulders and smiled. “Before you ring the bell,” she said, “be sure to know what tune it plays.”

And at that she turned and went into the woods, leaving the stone hall empty.

SNOW, GLASS, APPLES

BY NEIL GAIMAN

I do not know what manner of thing she is. None of us do. She killed her mother in the birthing, but that’s never enough to account for it.

They call me wise, but I am far from wise, for all that I foresaw fragments of it, frozen moments caught in pools of water or in the cold glass of my mirror. If I were wise I would not have tried to change what I saw. If I were wise I would have killed myself before ever I encountered her, before ever I caught him.

Wise, and a witch, or so they said, and I’d seen his face in my dreams and in reflections for all my life: sixteen years of dreaming of him before he reined his horse by the bridge that morning and asked my name. He helped me onto his high horse and we rode together to my little cottage, my face buried in the gold of his hair. He asked for the best of what I had; a king’s right, it was.

His beard was red-bronze in the morning light, and I knew him, not as a king, for I knew nothing of kings then, but as my love. He took all he wanted from me, the right of kings, but he returned to me on the following day and on the night after that: his beard so red, his hair so gold, his eyes the blue of a summer sky, his skin tanned the gentle brown of ripe wheat.

His daughter was only a child: no more than five years of age when I came to the palace. A portrait of her dead mother hung in the princess’s tower room: a tall woman, hair the color of dark wood, eyes nut-brown. She was of a different blood to her pale daughter.

The girl would not eat with us.

I do not know where in the palace she ate.

I had my own chambers. My husband the king, he had his own rooms also. When he wanted me he would send for me, and I would go to him, and pleasure him, and take my pleasure with him.

One night, several months after I was brought to the palace, she came to my rooms. She was six. I was embroidering by lamplight, squinting my eyes against the lamp’s smoke and fitful illumination. When I looked up, she was there.

“Princess?”

She said nothing. Her eyes were black as coal, black as her hair; her lips were redder than blood. She looked up at me and smiled. Her teeth seemed sharp, even then, in the lamplight.

“What are you doing away from your room?”

“I’m hungry,” she said, like any child.

It was winter, when fresh food is a dream of warmth and sunlight; but I had strings of whole apples, cored and dried, hanging from the beams of my chamber, and I pulled an apple down for her.

“Here.”

Autumn is the time of drying, of preserving, a time of picking apples, of rendering the goose fat. Winter is the time of hunger, of snow, and of death; and it is the time of the midwinter feast, when we rub the goose fat into the skin of a whole pig, stuffed with that autumn’s apples; then we roast it or spit it, and we prepare to feast upon the crackling.

She took the dried apple from me and began to chew it with her sharp yellow teeth.

“Is it good?”

She nodded. I had always been scared of the little princess, but at that moment I warmed to her and, with my fingers, gently, I stroked her cheek. She looked at me and smiled – she smiled but rarely – then she sank her teeth into the base of my thumb, the Mound of Venus, and she drew blood.

I began to shriek, from pain and from surprise, but she looked at me and I fell silent.

The little princess fastened her mouth to my hand and licked and sucked and drank. When she was finished, she left my chamber. Beneath my gaze the cut that she had made began to close, to scab, and to heal. The next day it was an old scar: I might have cut my hand with a pocketknife in my childhood.

I had been frozen by her, owned and dominated. That scared me, more than the blood she had fed on. After that night I locked my chamber door at dusk, barring it with an oaken pole, and I had the smith forge iron bars, which he placed across my windows.

My husband, my love, my king, sent for me less and less, and when I came to him he was dizzy, listless, confused. He could no longer make love as a man makes love, and he would not permit me to pleasure him with my mouth: the one time I tried, he started violently, and began to weep. I pulled my mouth away and held him tightly until the sobbing had stopped, and he slept, like a child.

I ran my fingers across his skin as he slept. It was covered in a multitude of ancient scars. But I could recall no scars from the days of our courtship, save one, on his side, where a boar had gored him when he was a youth.

Soon he was a shadow of the man I had met and loved by the bridge. His bones showed, blue and white, beneath his skin. I was with him at the last: his hands were cold as stone, his eyes milky blue, his hair and beard faded and lustreless and limp. He died unshriven, his skin nipped and pocked from head to toe with tiny, old scars.

He weighed near to nothing. The ground was frozen hard, and we could dig no grave for him, so we made a cairn of rocks and stones above his body, as a memorial only, for there was little enough of him left to protect from the hunger of the beasts and the birds.

So I was queen.

And I was foolish, and young – eighteen summers had come and gone since first I saw daylight – and I did not do what I would do, now.

If it were today, I would have her heart cut out, true. But then I would have her head and arms and legs cut off. I would have them disembowel her. And then I would watch in the town square as the hangman heated the fire to white-heat with bellows, watch unblinking as he consigned each part of her to the fire. I would have archers around the square, who would shoot any bird or animal that came close to the flames, any raven or dog or hawk or rat. And I would not close my eyes until the princess was ash, and a gentle wind could scatter her like snow.

I did not do this thing, and we pay for our mistakes.

They say I was fooled; that it was not her heart. That it was the heart of an animal – a stag, perhaps, or a boar. They say that, and they are wrong.

And some say (but it is her lie, not mine) that I was given the heart, and that I ate it. Lies and half-truths fall like snow, covering the things that I remember, the things I saw. A landscape, unrecognizable after a snowfall; that is what she has made of my life.

There were scars on my love, her father’s thighs, and on his ballock-pouch, and on his male member, when he died.

I did not go with them. They took her in the day, while she slept, and was at her weakest. They took her to the heart of the forest, and there they opened her blouse, and they cut out her heart, and they left her dead, in a gully, for the forest to swallow.

The forest is a dark place, the border to many kingdoms; no one would be foolish enough to claim jurisdiction over it. Outlaws live in the forest. Robbers live in the forest, and so do wolves. You can ride through the forest for a dozen days and never see a soul; but there are eyes upon you the entire time.

They brought me her heart. I know it was hers – no sow’s heart or doe’s would have continued to beat and pulse after it had been cut out, as that one did.

I took it to my chamber.

I did not eat it: I hung it from the beams above my bed, placed it on a length of twine that I strung with rowan berries, orange-red as a robin’s breast, and with bulbs of garlic.

Outside the snow fell, covering the footprints of my huntsmen, covering her tiny body in the forest where it lay.

I had the smith remove the iron bars from my windows, and I would spend some time in my room each afternoon through the short winter days, gazing out over the forest, until darkness fell.

There were, as I have already stated, people in the forest. They would come out, some of them, for the Spring Fair: a greedy, feral, dangerous people; some were stunted – dwarfs and midgets and hunchbacks; others had the huge teeth and vacant gazes of idiots; some had fingers like flippers or crab claws. They would creep out of the forest each year for the Spring Fair, held when the snows had melted.

As a young lass I had worked at the fair, and they had scared me then, the forest folk. I told fortunes for the fairgoers, scrying in a pool of still water; and later, when I was older, in a disk of polished glass, its back all silvered – a gift from a merchant whose straying horse I had seen in a pool of ink.

The stallholders at the fair were afraid of the forest folk; they would nail their wares to the bare boards of their stalls – slabs of gingerbread or leather belts were nailed with great iron nails to the wood. If their wares were not nailed, they said, the forest folk would take them and run away, chewing on the stolen gingerbread, flailing about them with the belts.

The forest folk had money, though: a coin here, another there, sometimes stained green by time or the earth, the face on the coin unknown to even the oldest of us. Also they had things to trade, and thus the fair continued, serving the outcasts and the dwarfs, serving the robbers (if they were circumspect) who preyed on the rare travelers from lands beyond the forest, or on gypsies, or on the deer. (This was robbery in the eyes of the law. The deer were the queen’s.)

The years passed by slowly, and my people claimed that I ruled them with wisdom. The heart still hung above my bed, pulsing gently in the night. If there were any who mourned the child, I saw no evidence: she was a thing of terror, back then, and they believed themselves well rid of her.

Spring Fair followed Spring Fair: five of them, each sadder, poorer, shoddier than the one before. Fewer of the forest folk came out of the forest to buy. Those who did seemed subdued and listless. The stallholders stopped nailing their wares to the boards of their stalls. And by the fifth year but a handful of folk came from the forest – a fearful huddle of little hairy men, and no one else.

The Lord of the Fair, and his page, came to me when the fair was done. I had known him slightly, before I was queen.

“I do not come to you as my queen,” he said.

I said nothing. I listened.

“I come to you because you are wise,” he continued. “When you were a child you found a strayed foal by staring into a pool of ink; when you were a maiden you found a lost infant who had wandered far from her mother, by staring into that mirror of yours. You know secrets and you can seek out things hidden. My queen,” he asked, “what is taking the forest folk? Next year there will be no Spring Fair. The travelers from other kingdoms have grown scarce and few, the folk of the forest are almost gone. Another year like the last, and we shall all starve.”

I commanded my maidservant to bring me my looking glass. It was a simple thing, a silver-backed glass disk, which I kept wrapped in a doeskin, in a chest, in my chamber.

They brought it to me then, and I gazed into it:

She was twelve and she was no longer a little child. Her skin was still pale, her eyes and hair coal-black, her lips blood-red. She wore the clothes she had worn when she left the castle for the last time – the blouse, the skirt – although they were much let-out, much mended. Over them she wore a leather cloak, and instead of boots she had leather bags, tied with thongs, over her tiny feet.

She was standing in the forest, beside a tree.

As I watched, in the eye of my mind, I saw her edge and step and flitter and pad from tree to tree, like an animal: a bat or a wolf. She was following someone.

He was a monk. He wore sackcloth, and his feet were bare and scabbed and hard. His beard and tonsure were of a length, overgrown, unshaven.

She watched him from behind the trees. Eventually he paused for the night and began to make a fire, laying twigs down, breaking up a robin’s nest as kindling. He had a tinderbox in his robe, and he knocked the flint against the steel until the sparks caught the tinder and the fire flamed. There had been two eggs in the nest he had found, and these he ate raw. They cannot have been much of a meal for so big a man.

He sat there in the firelight, and she came out from her hiding place. She crouched down on the other side of the fire, and stared at him. He grinned, as if it were a long time since he had seen another human, and beckoned her over to him.

She stood up and walked around the fire, and waited, an arm’s length away. He pulled in his robe until he found a coin – a tiny copper penny – and tossed it to her. She caught it, and nodded, and went to him. He pulled at the rope around his waist, and his robe swung open. His body was as hairy as a bear’s. She pushed him back onto the moss. One hand crept, spiderlike, through the tangle of hair, until it closed on his manhood; the other hand traced a circle on his left nipple. He closed his eyes and fumbled one huge hand under her skirt. She lowered her mouth to the nipple she had been teasing, her smooth skin white on the furry brown body of him.

She sank her teeth deep into his breast. His eyes opened, then they closed again, and she drank.

She straddled him, and she fed. As she did so, a thin blackish liquid began to dribble from between her legs…

“Do you know what is keeping the travelers from our town? What is happening to the forest people?” asked the Lord of the Fair.

I covered the mirror in doeskin, and told him that I would personally take it upon myself to make the forest safe once more.

I had to, although she terrified me. I was the queen.

A foolish woman would have gone then into the forest and tried to capture the creature; but I had been foolish once and had no wish to be so a second time.

I spent time with old books. I spent time with the gypsy women (who passed through our country across the mountains to the south, rather than cross the forest to the north and the west).

I prepared myself and obtained those things I would need, and when the first snows began to fall, I was ready.

Naked, I was, and alone in the highest tower of the palace, a place open to the sky. The winds chilled my body; goose pimples crept across my arms and thighs and breasts. I carried a silver basin, and a basket in which I had placed a silver knife, a silver pin, some tongs, a gray robe, and three green apples.

I put them on and stood there, unclothed, on the tower, humble before the night sky and the wind. Had any man seen me standing there, I would have had his eyes; but there was no one to spy. Clouds scudded across the sky, hiding and uncovering the waning moon.

I took the silver knife and slashed my left arm – once, twice, three times. The blood dripped into the basin, scarlet seeming black in the moonlight.

I added the powder from the vial that hung around my neck. It was a brown dust, made of dried herbs and the skin of a particular toad, and from certain other things. It thickened the blood, while preventing it from clotting.

I took the three apples, one by one, and pricked their skins gently with my silver pin. Then I placed the apples in the silver bowl and let them sit there while the first tiny flakes of snow of the year fell slowly onto my skin, and onto the apples, and onto the blood.

When dawn began to brighten the sky I covered myself with the gray cloak, and took the red apples from the silver bowl, one by one, lifting each into my basket with silver tongs, taking care not to touch it. There was nothing left of my blood or of the brown powder in the silver bowl, nothing save a black residue, like a verdigris, on the inside.

I buried the bowl in the earth. Then I cast a glamour on the apples (as once, years before, by a bridge, I had cast a glamour on myself), that they were, beyond any doubt, the most wonderful apples in the world, and the crimson blush of their skins was the warm color of fresh blood.

I pulled the hood of my cloak low over my face, and I took ribbons and pretty hair ornaments with me, placed them above the apples in the reed basket, and I walked alone into the forest until I came to her dwelling: a high sandstone cliff, laced with deep caves going back a way into the rock wall.

There were trees and boulders around the cliff face, and I walked quietly and gently from tree to tree without disturbing a twig or a fallen leaf. Eventually I found my place to hide, and I waited, and I watched.

After some hours, a clutch of dwarfs crawled out of the hole in the cave front – ugly, misshapen, hairy little men, the old inhabitants of this country. You saw them seldom now.

They vanished into the wood, and none of them espied me, though one of them stopped to piss against the rock I hid behind.

I waited. No more came out.

I went to the cave entrance and hallooed into it, in a cracked old voice.

The scar on my Mound of Venus throbbed and pulsed as she came toward me, out of the darkness, naked and alone.

She was thirteen years of age, my stepdaughter, and nothing marred the perfect whiteness of her skin, save for the livid scar on her left breast, where her heart had been cut from her long since.

The insides of her thighs were stained with wet black filth.

She peered at me, hidden, as I was, in my cloak. She looked at me hungrily. “Ribbons, goodwife,” I croaked. “Pretty ribbons for your hair…”

She smiled and beckoned to me. A tug; the scar on my hand was pulling me toward her. I did what I had planned to do, but I did it more readily than I had planned: I dropped my basket and screeched like the bloodless old peddler woman I was pretending to be, and I ran.

My gray cloak was the color of the forest, and I was fast; she did not catch me.

I made my way back to the palace.

I did not see it. Let us imagine, though, the girl returning, frustrated and hungry, to her cave, and finding my fallen basket on the ground.

What did she do?

I like to think she played first with the ribbons, twined them into her raven hair, looped them around her pale neck or her tiny waist.

And then, curious, she moved the cloth to see what else was in the basket, and she saw the red, red apples.

They smelled like fresh apples, of course; and they also smelled of blood. And she was hungry. I imagine her picking up an apple, pressing it against her cheek, feeling the cold smoothness of it against her skin.

And she opened her mouth and bit deep into it…

By the time I reached my chambers, the heart that hung from the roof beam, with the apples and hams and the dried sausages, had ceased to beat. It hung there, quietly, without motion or life, and I felt safe once more.

That winter the snows were high and deep, and were late melting. We were all hungry come the spring.

The Spring Fair was slightly improved that year. The forest folk were few, but they were there, and there were travelers from the lands beyond the forest.

I saw the little hairy men of the forest cave buying and bargaining for pieces of glass, and lumps of crystal and of quartz rock. They paid for the glass with silver coins – the spoils of my stepdaughter’s depredations, I had no doubt. When it got about what they were buying, townsfolk rushed back to their homes and came back with their lucky crystals, and, in a few cases, with whole sheets of glass.

I thought briefly about having the little men killed, but I did not. As long as the heart hung, silent and immobile and cold, from the beam of my chamber, I was safe, and so were the folk of the forest, and, thus, eventually, the folk of the town.

My twenty-fifth year came, and my stepdaughter had eaten the poisoned fruit two winters back, when the prince came to my palace. He was tall, very tall, with cold green eyes and the swarthy skin of those from beyond the mountains.

He rode with a small retinue: large enough to defend him, small enough that another monarch – myself, for instance – would not view him as a potential threat.

I was practical: I thought of the alliance of our lands, thought of the kingdom running from the forests all the way south to the sea; I thought of my golden-haired bearded love, dead these eight years; and, in the night, I went to the prince’s room.

I am no innocent, although my late husband, who was once my king, was truly my first lover, no matter what they say.

At first the prince seemed excited. He bade me remove my shift, and made me stand in front of the opened window, far from the fire, until my skin was chilled stone-cold. Then he asked me to lie upon my back, with my hands folded across my breasts, my eyes wide open – but staring only at the beams above. He told me not to move, and to breathe as little as possible. He implored me to say nothing. He spread my legs apart.

It was then that he entered me.

As he began to thrust inside me, I felt my hips raise, felt myself begin to match him, grind for grind, push for push. I moaned. I could not help myself.

His manhood slid out of me. I reached out and touched it, a tiny, slippery thing.

“Please,” he said softly. “You must neither move nor speak. Just lie there on the stones, so cold and so fair.”

I tried, but he had lost whatever force it was that had made him virile; and, some short while later, I left the prince’s room, his curses and tears still resounding in my ears.

He left early the next morning, with all his men, and they rode off into the forest.

I imagine his loins, now, as he rode, a knot of frustration at the base of his manhood. I imagine his pale lips pressed so tightly together. Then I imagine his little troupe riding through the forest, finally coming upon the glass-and-crystal cairn of my stepdaughter. So pale. So cold. Naked beneath the glass, and little more than a girl, and dead.

In my fancy, I can almost feel the sudden hardness of his manhood inside his britches, envision the lust that took him then, the prayers he muttered beneath his breath in thanks for his good fortune. I imagine him negotiating with the little hairy men – offering them gold and spices for the lovely corpse under the crystal mound.

Did they take his gold willingly? Or did they look up to see his men on their horses, with their sharp swords and their spears, and realize they had no alternative?

I do not know. I was not there; I was not scrying. I can only imagine…

Hands, pulling off the lumps of glass and quartz from her cold body. Hands, gently caressing her cold cheek, moving her cold arm, rejoicing to find the corpse still fresh and pliable.

Did he take her there, in front of them all? Or did he have her carried to a secluded nook before he mounted her?

I cannot say.

Did he shake the apple from her throat? Or did her eyes slowly open as he pounded into her cold body; did her mouth open, those red lips part, those sharp yellow teeth close on his swarthy neck, as the blood, which is the life, trickled down her throat, washing down and away the lump of apple, my own, my poison?

I imagine; I do not know.

This I do know: I was woken in the night by her heart pulsing and beating once more. Salt blood dripped onto my face from above. I sat up. My hand burned and pounded as if I had hit the base of my thumb with a rock.

There was a hammering on the door. I felt afraid, but I am a queen, and I would not show fear. I opened the door.

First his men walked into my chamber and stood around me, with their sharp swords, and their long spears.

Then he came in; and he spat in my face.

Finally, she walked into my chamber, as she had when I was first a queen and she was a child of six. She had not changed. Not really.

She pulled down the twine on which her heart was hanging. She pulled off the rowan berries, one by one; pulled off the garlic bulb – now a dried thing, after all these years; then she took up her own, her pumping heart – a small thing, no larger than that of a nanny goat or a she-bear – as it brimmed and pumped its blood into her hand.

Her fingernails must have been as sharp as glass: she opened her breast with them, running them over the purple scar. Her chest gaped, suddenly, open and bloodless. She licked her heart, once, as the blood ran over her hands, and she pushed the heart deep into her breast.

I saw her do it. I saw her close the flesh of her breast once more. I saw the purple scar begin to fade.

Her prince looked briefly concerned, but he put his arm around her nonetheless, and they stood, side by side, and they waited.

And she stayed cold, and the bloom of death remained on her lips, and his lust was not diminished in any way.

They told me they would marry, and the kingdoms would indeed be joined. They told me that I would be with them on their wedding day.

It is starting to get hot in here.

They have told the people bad things about me; a little truth to add savor to the dish, but mixed with many lies.

I was bound and kept in a tiny stone cell beneath the palace, and I remained there through the autumn. Today they fetched me out of the cell; they stripped the rags from me, and washed the filth from me, and then they shaved my head and my loins, and they rubbed my skin with goose-grease.

The snow was falling as they carried me – two men at each hand, two men at each leg – utterly exposed, and spreadeagled and cold, through the midwinter crowds, and brought me to this kiln.

My stepdaughter stood there with her prince. She watched me, in my indignity, but she said nothing.

As they thrust me inside, jeering and chaffing as they did so, I saw one snowflake land upon her white cheek, and remain there without melting.

They closed the kiln door behind me. It is getting hotter in here, and outside they are singing and cheering and banging on the sides of the kiln.

She was not laughing, or jeering, or talking. She did not sneer at me or turn away. She looked at me, though; and for a moment I saw myself reflected in her eyes.

I will not scream. I will not give them that satisfaction. They will have my body, but my soul and my story are my own, and will die with me.

The goose-grease begins to melt and glisten upon my skin. I shall make no sound at all. I shall think no more on this.

I shall think instead of the snowflake on her cheek.

I think of her hair as black as coal, her lips, redder than blood, her skin, snow-white.

THE TISSOT FAMILY CIRCUS

BY ANGELA SLATTER

The road into Pleasance does it no favours.

The big old welcome sign telling you where you are and how many souls are living there looks as if it’s not been maintained for some time – peeling paint, colours bleached by sun and wind and rain. The grass is high along the verge, the treeline thick and dark, and the scent of rotting vegetation carries on the breeze.

I’ve never been here before, but I’ve been lots of places like it. They all smell the same: desperation turned in on itself. Needless to say I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t have to be; doesn’t mean I’m not a little resentful, but I try to keep that to a minimum. Resentment just leads to worse things.

“Ichabod?” I say and receive absolutely no reaction whatsoever. So I clear my throat and yell, which has a spectacular effect on the bat-faced man snoozing beside me on the bench. Hurts his ears no doubt. He jerks awake, pulls at the reins and the two old roan mares, who’ve been doing perfectly well without his attention, protest the violence. They stop, look around and glare; stomp their feet in a delicate don’t fuck with us jig. “Ichabod, the next left, I think. Looks to be a field there.”

“Do you think I can’t see that?” he grumbles, even though his eyes have been closed for quite some while. “When exactly do you think I got demented, missy?”

If I were of a differing temperament – like my mother (and likely her mother before her and so on and so forth) – I might slap him up the side of the head. But he’s ancient, is Ichabod, and even given to impromptu naps as he is he still knows the old ways and the things we’re bound to do. He’s been at this longer than me, after all. So, I just pretend anticipation isn’t making my skin dance, clear my throat like that might pass for an apology, and he gees up the horses.

A ways ahead, the trees taper back and the road dips, widens, spears into what passes for the built-up area, darting off left and right to form streets on a neat grid. Very tidy but a tidiness from another era when some city planner with a penchant for sharp corners and straight lines held sway. That individual is long gone, I’m willing to bet. From the tiny knoll we’ve surmounted, I can see houses and shops, a brickworks chimney and a sawmill even further on; how much employment might they offer? Pleasance has the air of a spot that could be dying but doesn’t know it yet. Towards the outskirts on the other side are farms and pastures, cutting into the woods; from above it’ll look like jigsaw puzzle pieces.

Then up on the left a dirt track runs along beside the three-strand barbed wire fence. Ichabod takes it without comment and we follow until there’s a sagging ingress. Nothing else around, no houses, no barns. The pasture’s close enough to town for kids to find us; far enough there’re no witnesses. I climb down, feel the buzz pressing up through my boots, tell it to hush, and examine the gate. It’s rickety, and I’m trying to find where to put my fingers without getting splinters.

I fail. “Son of a bitch.”

“Tsk. Language,” admonishes Ichabod and I raise a middle finger in his direction without turning around. The wooden barrier protests but I’m gentle, lifting and carrying it like an aged aunt who has trouble getting out of her chair; the hinges squeak.

After the wagon rolls through, I close the gate again, amble as if there’s nothing fluttering inside me like want, and survey the area. Over by that stand of trees there’s a creek, I can hear it trickling in the early afternoon’s silence. No sign of cattle or sheep, no grazing animals. No one around.

In roughly the middle of the field I take the knife from the worn leather sheath at my belt. I hold my breath like I always do, and whisper the words he taught me but once. I don’t know their meaning because my lessons were brief and time was short; I only know what they do. The blade’s weirdly hot-cold on my palm as it slices. It heals fast, never leaves a scar. Anything that’s done to me now just slides right off – doesn’t mean nothing hurts.

Blood wells dark and red-blue, and I make a fist, release it, make a fist, release it, watch the little waterfall hit the grass, get soaked up like the earth’s greedy. I do this until I’m starting to feel dizzy, then wrap my pocket handkerchief around the hand.

I retrace my steps quickly, carefully, and climb up beside Ichabod once more. He’s alert, watching avidly. Leaning over, he says, “There’s just something a little bit spectacular when you do it. The old man? He was very workmanlike, but you, Evangeline? You’re an artist.”

Which makes me proud, though maybe it shouldn’t. But it does, and I watch too as if it’s the first time I’ve seen it. Deep breath, Evangeline, I think as the little circus begins to grow up from the ground and that tiny red sacrifice I give whenever we arrive at the place we need to be. It curls like a mist, all blues and purples and pinks, shading into vibrant oranges and reds, then yellows and greens, and back again and again. Swirling until things become solid and settled.

First come the little concession stands: Samuel’s Sweet Shop for all your sugary needs; Pearl’s Popcorn; Cora’s Candy Cotton; Harry’s Hushpuppies and Corndogs; Fidel’s Libations for the thickest malts or a jar of the best moonshine this side of any river you care to mention. Next, the games: the shooting gallery; the dime pitch; the milk bottle knockdown; test your strength and ring the bell. Each and every one rigged in some way, shape or form. On occasion the luck runs in the other direction, and we hand over a goldfish in a bag, a giant teddy bear, a fairy doll on a beribboned cane. The prizes look shiny and new, but anything you win from the Tissot Family Circus won’t exist in the morning; that’s just how it is. Doesn’t matter – we’re never around the next day, are we?

Now the carousel, brightly coloured and lit up like a small city, all those carved horses with golden bridles, hollowed-out swans, swirling teacups for folk to sit in. It remains my favourite – always was even before. It was the very first thing my eyes lit upon all those years ago – well, the second after the Impresario – but it was my first view of the circus per se. There’s something magical about it, the music and the movement, the speed, the sense that you’re no longer in the world, and that’s got a lot to recommend it to a lot of kids. Adults too. But kids especially.

Next, the cages and pens: a zebra and a giraffe; two big cats; three bears; and a small pool and slide set up with an ill-mannered troupe of otters and seals. There’s a petting farm with lambs, goats, calves, a donkey, a sleepy opossum with the good deal of personal charm required to overcome his looks. And a camel that thinks it’s a dog and acts accordingly – which is fortunate because Lord knows a camel has not really got the temperament for being petted.

Then at last the Big Top, pushing up like a big old pointy mushroom. Here, the clowns will carouse; the acrobats will tumble and do handstands and contort themselves like they’re made of rubber; Tilda will run her prancing ponies around the ring; the lion and tiger will sit on stools and pretend to be vicious; the fliers will take to the wires and tightropes high above the audience and the sawdust on the ground – no net because it’s not like it matters if any of them fall.