Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Jazzybee Verlag

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

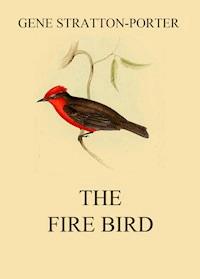

A fantastic work about the birds in the Limberlost swamp area in Indiana, USA. The book contains a wealth of character studies of native American birds as through friendly advances the author could induce to pose for her. Both text and pictures, of which there are almost forty in this edition, display an intimacy with the home life, the moods, the manners and customs of birds.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 227

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

What I have done with Birds

GENE STRATTON-PORTER

What I have done with birds, G. Stratton-Porter

Jazzybee Verlag Jürgen Beck

86450 Altenmünster, Loschberg 9

Deutschland

ISBN: 9783849648640

www.jazzybee-verlag.de

CONTENTS:

Chapter I -What I Have Done With Birds. 1

Chapter II - The "Queen" Rail: Rallus Elegans. 1

Chapter III - The Wood Thrush: Hylocichla Mustelina. 1

Chapter IV - The Barn Owl: Strix Pratincola. 1

Chapter V - The Killdeer: Oxyechus Vociferus. 1

Chapter VI - Black Vulture: Catharista Uruba. 1

Chapter VII - The Loggerhead Shrike: Lanius Ludovicianus. 1

Chapter VIII - The Purple Martin: Progne Subis. 1

Chapter IX - The Cat-bird: Galeoscoptes Caroliniensis. 1

Chapter X - The Belted Kingfisher: Ceryle Alcyon. 1

Chapter XI - The Yellow-Billed Cuckoo: Coccyzus Americanus. 1

Chapter XII - THE Blue Heron: Ardea Herodias. 1

Chapter XIII - The Mourning Dove: Zenaidura Macroura. 1

Chapter XIV - The Cow-Bird: Molothrus Ater1

Chapter XV - The Cardinal Grosbeak: Cardinalis Cardinais. 1

Chapter XVI - Robin: Merula Migratoria. 1

Chapter XVII - The Blue Jay: Cyanocitta cristata. 1

Chapter XVIII - The Humming-bird: Trochilus Colubris. 1

Chapter XIX - The Quail: Colinus Virginianus. 1

Cried Falco Sparverius: "I chased a mouse up this log.

Hooted Scops Asio: "I chased it down a little red lane."

'The bubbling brook doth leap when I come by,

Because my feet find measure with its call;

The birds know when the friend they love is nigh,

For I am known to them, both great and small.

The flower that on the lonely hillside grows

Expects me there when spring its bloom has given;

And many a tree and bush my wanderings knows,

And e'en the clouds and silent stars of heaven."

— Very.

Chapter I -WHAT I HAVE DONE WITH BIRDS

The greatest thing possible to do with a bird is to win its confidence. In a few days' work about most nests the birds can be taught so to trust me, that such studies can be made as are here presented of young and old, male and female.

I am not superstitious, but I am afraid to mistreat a bird,, and luck is with me in the indulgence of this fear. In all my years of field work not one study of a nest, or of any bird, has been lost by dealing fairly with my subjects. If a nest is located where access is impossible without moving it, an exposure is not attempted, and so surely as the sun rises on another morning, another nest of the same species is found within a few days, where a reproduction of it can be made.

Recently, in summing up the hardships incident to securing one study of a brooding swamp-bird, a prominent nature lover and editor said to me most emphatically, "That is not a woman's work."

"I do not agree with you," I answered. "In its hardships, in wading, swimming, climbing, in hidden dangers suddenly to be confronted, in abrupt changes from heat to cold, and from light to dark, field photography is not woman's work; but in the matter of finesse in approaching the birds, in limitless patience in awaiting the exact moment for the best exposure, in the tedious and delicate processes of the dark room, in the art of winning bird babies and parents, it is not a man's work. No man ever has had the patience to remain with a bird until he secured a real character study of it. A human mother is best fitted to understand and deal with a bird mother."

This is the basis of all my field work, — a mute contract between woman and bird. In spirit I say to the birds, "Trust me and I will do by you as I would be done by. Your nest and young shall be touched as I would wish some giant, surpassing my size and strength as I surpass yours, to touch my cradle and baby. I shall not tear down your home and break your eggs or take your naked little ones from the nest before they are ready to go, and leave them to die miserably. I shall come in colors to which you are accustomed, and move slowly and softly about, not approaching you too near until your confidence in me is established. I shall be most careful to feed your young what you feed them; drive away snakes and squirrels, and protect you in every way possible to me. Trust me, and go on with your daily life. For what small disturbance is unavoidable among you, forgive me, and through it I shall try to win thousands to love and shield you."

That I frequently have been able to teach a bird to trust me completely, these studies prove; but it is possible to go even further. After a week's work in a location abounding in every bird native to my state, the confidence of the whole feathered population has been won so that I could slip softly in my green dress from nest to nest, with not the amount of disturbance caused by the flight of a Crow or the drumming of a Woodpecker. This was proved to me when one day I was wanted at home, and a member of my family came quietly and unostentatiously, as she thought, through the wood to tell me. Every Wren began scolding. Every Cat-bird followed her with imperative questions.

WISDOM DUSKY FALCON

"A Dusky Falcon is beautiful and most intelligent'

Every Jay was on a high perch sounding danger signals. With a throb of great joy came the realization that I was at home and accepted of my birds; this other was a stranger, and her presence was feared and rejected.

So upon this basis I have gone among the birds, seeking not only to secure pictures of them by which family and species can be told, but also to take them perching in characteristic locations as they naturally alight in different circumstances; but best and above all else, to make each picture prove without text the disposition of the bird. A picture of a Dove that does not make that bird appear tender and loving, is a false reproduction. If a study of a Jay does not prove the fact that it is quarrelsome and obtrusive it is useless, no matter how fine the pose or portrayal of markings. One might write pages on the wisdom and cunning of the Crow, but one study of the bird that proved it would obviate the necessity of the text. A Dusky Falcon is beautiful and most intelligent, but who is going to believe it if you illustrate the statement with a sullen, sleepy bird, which serves only to furnish markings for natural -history identification? If you describe how bright and alert a Cardinal is, then see to it that you get a study of a Cardinal which emphasizes your statements.

A merry war has waged in the past few years over what the birds know; and it is all so futile. I do not know what the birds know, neither do you, neither does any one else, for that matter. There is no possible way to judge of the intelligence of birds, save by our personal experience with them, and each student of bird life will bring from the woods exactly what he went to seek, because he will interpret the actions of the birds according to his temperament and purpose.

If a man seeking material for a volume on natural history, trying to crowd the ornithology of a continent into the working lifetime of one person, goes with a gun, shooting specimens to articulate and mount from which to draw illustrations, he will no doubt testify that the birds are the wildest, shyest things alive, because that has been his experience with them.

If he goes with a note -book, a handful of wheat and the soul of a poet, he will write down the birds as almost human, because his own great heart humanizes their every action.

I go with a camera for the purpose of bringing from the fields and forests characteristic pictorial studies of birds, and this book is to tell and prove to you what my experiences have been with them. I slip among them in their parental hour, obtain their likenesses, and tell the story of how the work was accomplished. I was born in the country and grew up among the birds in a place where they were protected and fearless. A deep love for, and a comprehension of, wild things runs through the thread of my disposition, peculiarly equipping me to do these things.

In one season, when under ten years of age, I located sixty nests, and I dropped food into the open beaks in every one of them. Soon the old birds became so accustomed to me, and so convinced of my good intentions, that they would alight on my head and shoulders in a last hop to reach their nests with the food they had brought. Playing with the birds was my idea of fun. Pets were my sort of dolls. It did not occur to me that I was learning anything that would be of use in after years; now comes the realization that knowledge acquired for myself in those days is drawn upon every time I approach the home of a bird.

When I decided that the camera was the only method by which to illustrate my observations of bird life, all that was necessary to do was to get together my outfit, learn how to use it, to compound my chemicals, to develop and fix my plates, and tone and wash my prints. How to approach the birds I knew better than anything else.

This work is to tell of and to picture my feathered friends of the woods in their homes. When birds are bound to their nests and young by the brooding fever, especially after the eggs have quickened to life, it is possible to cultivate, by the use of unlimited patience and bird sense, the closest intimacy with them and to get almost any pose or expression you can imagine.

ANGER CHICKEN-HAWK

"I once snapped a Chicken-hawk with a perfect expression of anger on his face"

In living out their lives, birds know anger, greed, jealousy, fear and love, and they have their playtimes. In my field experiences I once snapped a Chicken-hawk with a perfect expression of anger on his face, because a movement of mine disturbed him at a feast set to lure him within range of my camera. No miser ever presented a more perfect picture of greed than I frequently caught on the face of a young Black Vulture to which it was my daily custom to carry food. Every day in field work one can see a male bird attack another male, who comes fooling around his nest and mate, and make the feathers fly. Did humanity ever present a specimen scared more than this Sheilpoke when he discovered himself between a high embankment and the camera, and just for a second hesitated in which direction to fly? Sometimes by holding food at unexpected angles young birds can be coaxed into the most astonishing attitudes and expressions.

I use four cameras suited to every branch of field work, and a small wagon-load of long hose, ladders, waders and other field paraphernalia.

Backgrounds never should be employed, as the use of them ruins a field study in two ways. At one stroke they destroy atmosphere and depth of focus.

Nature's background, for any nest or bird, is one of ever shifting light and shade, and this forms the atmosphere without which no picture is a success. Nature's background is one of deep shadow, formed by dark interstices among the leaves, dense thickets and the earth peeping through; and high lights formed by glossy leaves, flowers and the nest and eggs, if they are of light color.

Nature revels in strong contrasts of light and shade, sweet and sour, color and form. The whole value of a natural-history picture lies in reproducing atmosphere, which tells the story of out-door work, together with the soft high lights and velvet shadows which repaint the woods as we are accustomed to seeing them. It is not a question of timing; on nests and surroundings all the time wanted can be had; on young and grown birds, snap shots must be resorted to in motion, but frequently, with them, more time than is required can be given. It is a question of whether you are going to reproduce nature and take a natural -history picture, or whether you are going to insert a background and take a sort of flat Japanese, two-tone, wash effect, fit only for decoration, never to reproduce the woods.

Also in working about nests when the mother bird is brooding, the idea is, or should be, to make your study and get away speedily; and this is a most excellent reason from the bird's side of the case as to why a background never should be introduced. In the first place, if you work about a nest until the eggs become chilled the bird deserts them, and a brood is destroyed. On fully half the nests you will wish to reproduce, a background could not be inserted without so cutting and tearing out foliage as to drive the bird to desert; to let in light and sunshine, causing her to suffer from heat, and so to advertise her location that she becomes a prey to every thoughtless passer. The birds have a right to be left exactly as you find them.

It is a good idea when working on nests of young birds, where you have hidden cameras in the hope of securing pictures of the old, and must wait some time for them to come, to remember that nestlings are accustomed to being fed every ten or fifteen minutes, and even oftener. If you keep the old ones away long, you subject the young to great suffering and even death; so go to the woods prepared, if such case arise, to give them a few bites yourself. In no possible way can it hurt a young bird for you to drop into its maw a berry or worm of the kind its parents feed it, since all the old bird does, in the majority of cases, is to pick a worm or berry from the bushes and drop it into the mouth of the young.

GREED – BLACK VULTURE

"No miser ever presented a more perfect picture of greed than I frequently caught on the face of this vulture."

In case you do not know what to feed a nestling, an egg put on in cold water, brought to a boil and boiled twenty minutes, then the yolk moistened with saliva, is always safe for any bird. While you are working so hard for what you want yourself, just think of the birds and what they want occasionally.

The greatest brutality ever practiced on brooding birds consists in cutting down, tearing out and placing nests of helpless young for your own convenience. Any picture so taken has no earthly value, as it does not reproduce a bird's location or characteristics. In such a case the rocking of the branches, which is cooling to the birds, is exchanged for a solid location, and the leaves of severed limbs quickly wither and drop, exposing both old and young to the heat, so that your pictures represent, not the free wild life of thicket and wood, but tormented creatures lolling and bristling in tortures of heat, and trying to save their lives under stress of forced and unnatural conditions. If you can not reproduce a bird's nest in its location and environment, your picture has not a shred of historical value. My state imposes heavy fines for work of this sort and soon all others will do the same.

The eggs of almost all birds are pointed and smaller at one end than the other, and mother birds always place these points together in the center of the nest. If you wish to make a study of a nest for artistic purposes, bend the limb but slightly, so that the merest peep of the eggs shows, and take it exactly as the mother leaves it. If you desire it for historical purposes, reproduce it so that students can identify a like nest from it. Bend the limb lower so that the lining will show, as well as outside material, and with a little wooden paddle turn at least one egg so that the shape and markings are distinct. This can not possibly hurt the egg and when the bird returns to brood she will replace it to suit herself.

If you find statements in the writings of a natural-history photographer that you can not corroborate in the writings of your favorite ornithologist, be reasonable. Who is most likely to know? The one who tries to cover the habits and dispositions of the birds of a continent in the lifetime of one person, or the one who, in the hope of picturing one bird, lies hidden by the day watching a nest? Sometimes a series of one bird covers many days, sometimes weeks, as the Kingfisher; sometimes months, as the Vulture; and sometimes years, as did the Cardinals of this book. Does it not stand to reason that, in such intimacy with a few species, much can be learned of them that is new?

All that my best authority on our native birds can say of the eggs of a Quail is that they are "roundish." He hesitates over the assertion that Cardinals eat insects, and states for a fact that they brood but once a season. No bird is so completely a seed- or insect-eater that it does not change its diet. Surely the Canaries of your cages are seed-eaters, yet every Canary-lover knows that if the bird's diet is not varied with lettuce, apple, egg and a bit of raw beefsteak occasionally, it will pull out its feathers and nibble the ends of them for a taste of meat. Chickens will do the same thing.

FEAR – SHEILPOKE

"Did humanity ever present a specimen scared more than this Sheilpoke?"

Certainly Cardinals eat insects, quite freely. The one lure effective above all others in coaxing a Cardinal before a lens was fresh, bright red, scraped beefsteak. Nine times out of ten this bird went where I wanted him when a dead limb set with raw meat was introduced into his surroundings. He would venture for that treat what he would not for his nestlings. And how his sharp beak did shear into it!

Ornithologists tell us that the diet of a Black Vulture is carrion. To reasonable people that should be construed as a general principle, and not taken to mean that if a Vulture eats a morsel of anything else it can not be a Vulture. Once during a Vulture series in the Limberlost a bird of this family in close quarters presented me with his dinner. In his regurgitations there were dark streaks I did not understand, and so I investigated. They were grass! Later I saw him down in a fence-corner, snipping grass like a Goose, and the week following his mate ate a quantity of catnip with evident relish. Then some red raspberries were placed in the door of their log and both of them ate the fruit.

In the regurgitations of a Kingfisher there can be found the striped legs of grasshoppers and the seeds of several different kinds of berries. All grain- and seed-eaters snap up a bug or worm here and there. All insect-eaters vary their diet with bugs and berries and all meat- and carrion-eaters crave some vegetable diet.

Through repeated experience with the same pairs I know that Cardinals of my locality nest twice in a season, and I believe there are cases where they do three times, as I have photographed young in a nest as late as the twenty-ninth of August. Had it not been that a pair were courting for a second mating about a nest still containing their young, almost ready to go, such a picture as this pair of Courting Cardinals never would have been possible to me. But after one brooding they became so accustomed to me that they flitted about their home, making love as well as feeding the nestlings. Repeatedly in my work I have followed a pair of cardinals from one nest to a new location a few rods away where they continued operations about a second brooding.

Neither does an authority who tells you certain kinds of birds are the same size, male and female, mean anything except that they are the same on an average. All accepted authorities state that Black Vultures are the same size. My male of the Limberlost was a tough old bird, of what age no one could guess, his eyes dim, his face wrinkled and leathery, his feet incrusted with scale, and he was almost as large as his cousin, Turkey Buzzard. His mate was a trim little hen of the previous year, much smaller and in every way fresh compared with him, but they were mated and raising their family. No ornithologist can do more than lay down the general rules, and trust to your good sense to recognize the exceptions.

There are pairs of birds in which the male is a fine big specimen, the female small and insignificant. There are pairs where the female is the larger and finer, and where they are the same size. Sometimes they conform in color and characteristics to the rules of the books and again they do not. Twice in my work I have found a white English Sparrow, also a Robin, wearing a large white patch on his coat. I once came within a breath of snapping an old Robin of several seasons with a tail an inch long. It did not appeal to me that he was a short -tailed species of Robin, — there is a way to explain all these things. The bird had been in close quarters and relaxed his muscles, letting his tail go to save his body.

A large volume could be filled with queer experiences among birds. Once I found a baby Robin that had been fed something poisonous and its throat was filled with clear, white blisters, until its beak stood wide open and it was gasping for breath. I punctured the blisters with a needle and gave it some oil, but it died. Another time I rescued a Robin that had hung five inches below its nest by one leg securely caught in a noose of horsehair, until the whole leg was swollen, discolored, the skin cut and bleeding, and the bird almost dead. Release was all it needed.

LOVE – CARDINAL GROSBEARS

"Male cardinal in pursuit of a mate."

Again I came across a Scarlet Tanager a few days before leaving the nest, and both its eyes were securely closed and hidden by a thick plastering of feathers and filth. I took it home, soaked and washed it perfectly clean in warm milk. Its eyes were a light pink and seemed sightless. It was placed in the dark, fed carefully, gradually brought to the light and in three days it could see perfectly and was returned to its nest, sound as the other inmates.

Once I found a female Finch helpless on the ground, and discovered her trouble to be an egg so large she could not possibly deposit it, and she had left the nest and was struggling in agony. I broke the egg with a hatpin and she soon flew away, seemingly all right. With the help of a man who climbed a big tree and secured the egg of a Chicken-hawk, after the Hawk had been shot by a neighboring farmer, we played the mean trick on a Hen of having her brood on the egg of her enemy.

Another time some boys came to me with a stringy baby Sheilpoke, scarce old enough to fly, that had landed aimlessly in a ditch filled with crude oil, and the poor bird was miserable past description. Warm water, soft soap and the scrub brush ended his troubles and he was returned to the river clean, full fed and happy, I hope. Walking through the woods one Sabbath morning this spring, after a night of high wind and driving rain, I was attracted by the sharp alarm cries of a pair of Rose-breasted Grosbeaks. I followed them until almost mired in the swamp,, and there, on a little tuft of grass, between pools of water and among trampling cattle, within two feet of each other, I found a male baby Grosbeak and a Scarlet Tanager, neither over five days from the shell. The Tanager nest I could not discover. The Grosbeak was in a slender oak sapling in a thicket of grape-vines. The tree was too light to bear my weight and I was not prepared for field work. To leave them meant for them to be drowned or trampled by the cattle. I carried them both home in my hands. That night I read that a young Hawk taken from his coarse nest of sticks and placed in a soft nest would die miserably, so the next morning I took a ladder and went back to the swamp. There had been some woodland tragedy other than the storm. The nest contained one baby, dead and badly abused, so I carefully cut the surrounding vines and brought the cradle home to my bird. For the next ten days, in the midst of my busiest time on this book, a stop every fifteen minutes was made to feed those youngsters a mixture of boiled potato and egg, varying with a little mashed fruit and bread and milk.

HILARITY - KINGFISHER

They grew beautifully. When they were large enough to fly well they were given the freedom of the conservatory, then the door was left open, and finally they were placed in an apple-tree with food and water beneath. As I write they are six weeks old. Bath water is still furnished them, but they have not been fed for ten days. Both of them are flying about the orchard, clean, bright, beautiful birds. I was most anxious to keep them, the Grosbeak especially. It would have made a precious pet, but the laws of my state prohibit the caging of a song-bird, so I gradually had to accustom them to become self-supporting, take their pictures, and let them go.

While working among and about birds in the nesting season I have secured these intimate studies and experiences. At any other time, when they are the wild, shy, free creatures of all outdoors, a preconceived study of them is the merest chance, and a stray snap shot, luck pure and simple. This, of course, refers to songsters. With coast and tropical birds that live in flocks it is different.

But don t let any one imagine that because he knows his natural history well, he knows anything about the camera. That is a separate and distinct study. You might as well ask a great surgeon to do X-ray work without knowing how, as to ask a scientist to judge of a natural-history photographer's work. It is possible to locate a favorite stump and photograph one or a pair of Kingfishers in the act of diving for food. It is possible by his hen's nest containing egg of chicken-hawk droppings to locate a Pheasant's drumming log, hide a camera and take him drumming, fighting another cock, or mating. It is possible to locate a Heron's fishing grounds and take him frogging at any time in the season. These are the things which seldom happen, and which are rare luck, but they are perfectly possible to one who has mastered the art of setting and hiding a camera and making the most of a poor plate.

I have done some of these things; but for the most part these are simple little stories of what occurs every day in field work. What I Have Done with Birds will tell how they were approached, to what extent their confidence was gained, and how much time was required; it will show the studies and will explain what of courage, strength and patience they cost.

My closet contains hundreds of negatives of nests, young birds, fully feathered on the day of leaving the nest and mostly in pairs, several series from nests to grown birds, some extending over three months; and grown birds in the act of diving, bathing, flying, singing, in anger, greed, fear, taking a sun bath, and courting. I have two studies of birds when the pair were forming their partnership, one of a male bird standing sentinel beside his brooding mate, and one of a pair of Kingfishers on a stump in their favorite fishing shoal. Some of these studies were made from blinds, some with hidden covered cameras and long hose, and some with the camera in plain sight and the lens not ten feet from the subject.

In cases where nestlings are similar in form and coloring to their elders and will answer every historical purpose as well, I have preferred to use the young in pairs in these illustrations, because my heart is peculiarly tender over these plump, dainty, bright-eyed little creatures, and I fancy others will feel the same.

Every picture reproduced is of a living bird, perching as it alighted in a characteristic environment. I have no gallery save God's big workshop of field and forest, and my birds are bound by no tie save the chord of sympathy between us.