Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Crossway

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

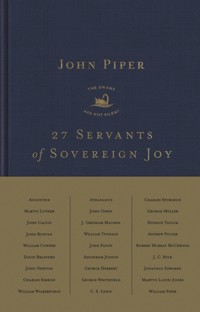

From Bestselling Author John Piper: 27 Biographies of Notable Figures from Church History, including Augustine, John Calvin, and Martin Luther Throughout church history, the faithful ministries of Christian leaders—though full of struggle, sin, and weakness—have magnified the worth and majesty of God. Their lives and teachings are still profoundly relevant. Their voices live on in the stories we read and tell today. In this book, John Piper celebrates the lives of 27 such leaders from church history, offering a close look at their perseverance amidst opposition, weakness, and suffering. Let the resilience of these faithful but flawed saints inspire you toward a life of Christ-exalting courage, passion, and joy. - Written by Best-Selling Author John Piper: The author of more than 50 books, including Desiring God; Don't Waste Your Life; Providence; The Supremacy of God in Preaching; Expository Exultation; and Why I Love the Apostle Paul - Short Biographies of 27 Inspiring Figures from Church History: Features short biographies of Augustine, John Calvin, John Bunyan, Martin Luther, John Newton, William Wilberforce, and more - Updated from 21 Servants of Sovereign Joy: Includes new chapters about Martyn Lloyd-Jones, Jonathan Edwards, Bill Piper, J. C. Ryle, Andrew Fuller, and Robert Murray McCheyne

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1786

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Thank you for downloading this Crossway book.

Sign up for the Crossway Newsletter for updates on special offers, new resources, and exciting global ministry initiatives:

Crossway Newsletter

Or, if you prefer, we would love to connect with you online:

“These studies are gems, often looking at well-known figures in a fresh light. Now we have all twenty-seven of these studies brought together in one fat volume. If you want to be stirred and challenged by the Christ who stirred and challenged these twenty-seven servants of sovereign joy, look no further.”

D. A. Carson, Cofounder and Theologian-at-Large, The Gospel Coalition

“27 Servants of Sovereign Joy is a landmark book. A cursory look at the table of contents might lead one to expect a retreading of familiar material, but the book is a triumph of originality—so much so that I do not hesitate to call it a page-turner. Piper does a wonderful job of taking us into unexpected corners of his subjects’ lives and writings. The book is a monument of research and scholarship. Of course, the final effect is spiritual edification, which the book conveys in abundance. The scope of the book and quantity of detail is breathtaking.”

Leland Ryken, Emeritus Professor of English, Wheaton College

“Good biographies are almost like another kind of Bible commentary, illustrating and confirming the faithfulness of God in the lives of his people. This collection brings together portraits from a variety of times and contexts that can hugely enrich us in our own. Highly recommended.”

Sam Allberry, pastor; apologist; author, What God Has to Say about Our Bodies

“John Piper is a vivacious storyteller with a profound ability to weave together a meticulously intimate portrait of God’s sovereign joy set ablaze in the human story. These twenty-seven biographies are a passionately compelling reminder that we are surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses that bid us to persistently endure the race set before us. What a gift to have this compilation now in one volume—highly accessible, warmly pastoral, and decidedly focused on the grace of Christ shining through the lives of sinners, chosen by God, and used for his glory.”

Dustin Benge, Associate Professor of Biblical Spirituality and Historical Theology, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary; author, The Loveliest Place

“27 Servants of Sovereign Joy is a cornucopia of moving and motivating biographies of leaders whose lives have left a lasting impact. John Piper’s assembly of heroes reveals a company of struggling saints who nevertheless faithfully persevered through weakness, doubt, and adversity. These tales told by a master storyteller will inspire and encourage both leaders and readers to deeper commitment for Christ.”

Peter Lillback, President, Westminster Theological Seminary

27 Servants of Sovereign Joy

Other Crossway Books by John Piper

Bloodlines

The Collected Works of John Piper

Coronavirus and Christ

Don’t Waste Your Life

Expository Exultation

Fifty Reasons Why Jesus Came to Die

The Future of Justification

God Is the Gospel

God’s Passion for His Glory

A Hunger for God

A Peculiar Glory

Providence

Reading the Bible Supernaturally

Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood

Seeing and Savoring Jesus Christ

Spectacular Sins

The Supremacy of God in Preaching

Think

This Momentary Marriage

What Is Saving Faith?

What Jesus Demands from the World

When I Don’t Desire God

Why I Love the Apostle Paul

27 Servants of Sovereign Joy

Faithful, Flawed, and Fruitful

John Piper

27 Servants of Sovereign Joy: Faithful, Flawed, and Fruitful

Copyright © 2022 by Desiring God Foundation

Published by Crossway1300 Crescent StreetWheaton, Illinois 60187

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except as provided for by USA copyright law. Crossway® is a registered trademark in the United States of America.

Cover design: Josh Dennis

First printing 2022

Printed in the United States of America

In Books 1–2

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from The New American Standard Bible®. Copyright © The Lockman Foundation 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995. Used by permission.

In Books 3–9

Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

———

Scripture quotations marked AT are the author’s translation.

Scripture quotations marked ESV are from the ESV® Bible (The Holy Bible, English Standard Version®), copyright © 2001 by Crossway, a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations marked KJV are from the King James Version of the Bible. Public domain.

Scripture quotations marked NASB are from The New American Standard Bible®. Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. www.Lockman.org.

Scripture quotations marked NKJV are taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Scripture quotations marked RSV are from the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1946, 1952, and 1971 the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

All emphases in Scripture quotations have been added by the author.

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-4335-7847-2 ePub ISBN: 978-1-4335-7850-2 PDF ISBN: 978-1-4335-7848-9 Mobipocket ISBN: 978-1-4335-7849-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Piper, John, 1946- author.

Title: 27 servants of sovereign joy : faithful, flawed, and fruitful / John Piper.

Description: Wheaton, Illinois : Crossway, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021021517 (print) | LCCN 2021021518 (ebook) | ISBN 9781433578472 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781433578489 (pdf) | ISBN 9781433578496 (mobi) | ISBN 9781433578502 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Christian biography. | Church history.

Classification: LCC BR1700.3 .P554 2022 (print) | LCC BR1700.3 (ebook) | DDC 658.4/092--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021021517

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021021518

Crossway is a publishing ministry of Good News Publishers.

2022-04-07 03:37:31 PM

Contents

Preface

Book 1: The Legacy of Sovereign Joy

Augustine

Martin Luther

John Calvin

Book 2: The Hidden Smile of God

John Bunyan

William Cowper

David Brainerd

Book 3: The Roots of Endurance

John Newton

Charles Simeon

William Wilberforce

Book 4: Contending for Our All

Athanasius

John Owen

J. Gresham Machen

Book 5: Filling Up the Afflictions ofChrist

William Tyndale

John G. Paton

Adoniram Judson

Book 6: Seeing Beauty and Saying Beautifully

George Herbert

George Whitefield

C. S. Lewis

Book 7: A Camaraderie of Confidence

Charles Spurgeon

George Müller

Hudson Taylor

Book 8: The Power of Doctrinal Holiness

Andrew Fuller

Robert Murray McCheyne

J. C. Ryle

Book 9: The Passionate Pursuit of Revival and Christ-Exalting Joy

Jonathan Edwards

Martyn Lloyd-Jones

Bill Piper

Publication Information

Desiring God Note on Resources

Preface

It brings me a great deal of pleasure at the beginning of this volume of collected biographies to pay tribute to a man without whom they would, in all likelihood, not exist. Iain Murray sowed the seeds from which this has all grown. There is a story behind this claim.

The Story behind the Tribute

During my first seven years in the pastoral ministry (1980–1987), I felt very green—inexperienced, and in some ways unprepared. Before coming to Bethlehem Baptist Church at the age of thirty-four, I had never been a pastor. I was in school full-time till I was twenty-eight and then taught college Bible courses until God called me to the pastoral ministry.

In seminary, I had avoided pastoral courses and taken as many exegetical courses as I could, not at all expecting to be a pastor. When I came to Bethlehem, I had never performed a funeral, never stood by the bed of a dying person, never led a council of elders or any other kind of council or committee, never baptized anyone, never done a baby dedication, and had only preached a couple dozen sermons in my life. That’s what I mean by green.

During those first seven years, one of the ways I pursued wisdom for the pastoral work in front of me was the reading of pastoral biographies. For example, I devoured Warren Wiersbe’s two volumes, Walking with the Giants: A Minister’s Guide to Good Reading and Great Preaching (1976) and Listening to the Giants: A Guide to Good Reading and Great Preaching (1980). Together they contained over thirty short biographies of men in pastoral ministry.

But one of the most enjoyable and inspiring things I did to deepen my grasp of the pastoral calling was to listen to a master life-storyteller, Iain Murray. Murray had been a pastoral assistant with Martyn Lloyd-Jones in London and had served as a pastor in two churches in England and Australia. He is a cofounder of the Banner of Truth Trust and has devoted a great part of his life to biographical writing.

He is well-known for his biographies of Martyn Lloyd-Jones and Jonathan Edwards, to mention only two. But not as many people know that Iain Murray is a master at taking an hour in a ministerial conference and telling the story of a great Christian in a way that instructs and inspires. For example, even today you can go online and find the (forty-plus-year-old) audio stories of Charles Spurgeon, Robert Dabney, William Tyndale, Ashbel Green, George Whitefield, John Knox, John Newton, William Jay, Thomas Hooker, and more.

The Latest Technology: Walkman

The latest technology in the early 1980s was the Walkman—a small cassette player that let me take Murray with me on my morning jogs or into the car. I listened to everything biographical I could get. This stoked the embers of my affections for biography. It has always felt to me that biography is one of the most enjoyable, edifying, and efficient ways to read history. Enjoyable because we all love a good story and the ecstasies and agonies of real life. Edifying because the faithfulness of God in the lives of contrite, courageous, forgiven sinners is strengthening for our own faith. Efficient because, in a good biography, you not only learn about a person’s life but also about theology, psychology, philosophy, ethics, politics, economics, and church history. So I have long been a lover of biography.

I could be wrong, but my own opinion is that this volume would not exist without the inspiring ministry of Iain Murray’s audio tapes. In 1987, it seemed to me that there was a need for a conference for pastors that would stir up a love for “the doctrines of grace,” a zeal for the beauty of the gospel, a passion for God-centered preaching, a commitment to global missions, and a joy in Christ-exalting worship.

A Conference and Book Series Are Born

The first Bethlehem Conference for Pastors took place in 1988. Inspired by Iain Murray, I gave a biographical message every year for the next twenty-seven years. That is where the mini-biographies in this volume come from (which means that all these chapters can be heard in audio form at www.desiringGod.org). Throughout the year before each conference, I would read about the life and ministry of some key figure in church history. Then I would decide on some thematic focus to give unity to the message, and I would try to distill my reading into an hour-long message. The messages—and the edited versions—are unashamedly hortatory. I aim to teach and encourage. I also aim never to distort the truth of a man’s life and work. But I do advocate for biblical truths that his life illustrates.

This volume contains nine collections with three historical figures each. The series was published under the title The Swans Are Not Silent. You can read the story behind that title in the preface to The Legacy of Sovereign Joy. But the gist of it is this: when Augustine died, his successor felt so inadequate that he said, “The cricket chirps, the swan is silent.” The point of the series title is that, through biography, the swans are not silent! Augustine was not the only great voice that lives on. Thousands of voices live on. And their stories should be told and read.

Biography Is Biblically Mandated

It would be wonderfully rewarding to me if I heard that your reading of these stories brought you as much joy as I received in researching and writing them. If you need a greater incentive than that prospect, remember Hebrews 11. Surely this chapter is a divine mandate to read Christian biography. I wrote a chapter in Brothers, We Are Not Professionals that tried to make this case. It was titled “Brothers, Read Christian Biography.” I commented on Hebrews 11,

The unmistakable implication of the chapter is that if we hear about the faith of our forefathers (and mothers), we will “lay aside every weight and sin” and “run with endurance the race that is set before us” (Heb. 12:1). If we asked the author, “How shall we stir one another up to love and good works?” (10:24), his answer would be: “Through encouragement from the living andthe dead” (10:25; 11:1–40). Christian biography is the means by which the “body life” of the church cuts across the centuries.1

Countless Benefits

I think that what was said of Abel in Hebrews 11:4 can be said of any saint whose story is told: “Through his faith, though he died, he still speaks” (ESV). It has been a great pleasure as I have listened to these voices. But not only a pleasure. They have strengthened my hand in the work of the ministry again and again. They have helped me feel that I was part of something much bigger than myself or my century. They have showed me that the worst of times are not the last of times, and they made the promise visible that God works all things for our good. They have modeled courage and perseverance in the face of withering opposition. They have helped me set my face to the cause of truth and love and world evangelization. They have revived my love for Christ’s church. They have reinforced my resolve to be a faithful husband and father. They have stirred me up to care about seeing and savoring the beauty of God. They inspired the effort to speak that beauty in a way that it doesn’t bore. They quickened a love for Christian camaraderie in the greatest Cause in the world. And they did all this—and more—in a way that caused me to rejoice in the Lord and be glad I was in his sway and his service.

I pray that all of this and more will be your pleasure and your profit as you read or listen. For the swans are definitely not silent.

John Piper

July 2016

1 John Piper, Brothers, We Are Not Professionals (Nashville, TN: B&H, 2013), 106–12.

Book 1

The Legacy of Sovereign Joy

God’s Triumphant Grace in the Lives of Augustine, Luther, and Calvin

To Jon Bloom

whose heart and hands

sustain the song

at the Bethlehem Conference for Pastors

and Desiring God Ministries

Book 1 | The Legacy of Sovereign Joy

Contents

Preface

Acknowledgments

Introduction: Savoring the Sovereignty of Grace in the Lives of Flawed Saints

1 Sovereign Joy

The Liberating Power of Holy Pleasure in the Life and Thought of St. Augustine

2 Sacred Study

Martin Luther and the External Word

3 The Divine Majesty of the Word

John Calvin: The Man and His Preaching

Conclusion: Four Lessons from the Lives of Flawed Saints

The sum of all our goods, and our perfect good, is God. We must not fall short of this, nor seek anything beyond it; the first is dangerous, the other impossible.

St. Augustine Morals of the Catholic Church

Book 1

Preface

At the age of seventy-one, four years before he died on August 28, AD 430, Aurelius Augustine handed over the administrative duties of the church in Hippo on the northern coast of Africa to his assistant Eraclius. Already, in his own lifetime, Augustine was a giant in the Christian world. At the ceremony, Eraclius stood to preach as the aged Augustine sat on his bishop’s throne behind him. Overwhelmed by a sense of inadequacy in Augustine’s presence, Eraclius said, “The cricket chirps, the swan is silent.”1

If only Eraclius could have looked down over sixteen centuries at the enormous influence of Augustine, he would have understood why the series of books beginning with The Legacy of Sovereign Joy is titled The Swans Are Not Silent. For 1,600 years, Augustine has not been silent. In the 1500s, his voice rose to a compelling crescendo in the ears of Martin Luther and John Calvin. Luther was an Augustinian monk, and Calvin quoted Augustine more than any other church father. Augustine’s influence on the Protestant Reformation was extraordinary. A thousand years could not silence his song of jubilant grace. More than one historian has said, “The Reformation witnessed the ultimate triumph of Augustine’s doctrine of grace over the legacy of the Pelagian view of man”2—the view that man is able to triumph over his own bondage to sin.

The swan also sang in the voice of Martin Luther in more than one sense. All over Germany you will find swans on church steeples, and for centuries Luther has been portrayed in works of art with a swan at his feet. Why is this? The reason goes back a century before Luther. John Hus, who died in 1415, a hundred years before Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses on the Wittenberg door (1517), was a professor and later president of the University of Prague. He was born of peasant stock and preached in the common language instead of Latin. He translated the New Testament into Czech, and he spoke out against abuses in the Catholic Church.

“In 1412 a papal bull was issued against Hus and his followers. Anyone could kill the Czech reformer on sight, and those who gave him food or shelter would suffer the same fate. When three of Hus’s followers spoke publicly against the practice of selling indulgences, they were captured and beheaded.”3 In December 1414, Hus himself was arrested and kept in prison until March 1415. He was kept in chains and brutally tortured for his views, which anticipated the Reformation by a hundred years.

On July 6, 1415, he was burned at the stake along with his books. One tradition says that in his cell just before his death, Hus wrote, “Today, you are burning a goose [the meaning of ‘Hus’ in Czech]; however, a hundred years from now, you will be able to hear a swan sing; you will not burn it, you will have to listen to him.”4 Martin Luther boldly saw himself as a fulfillment of this prophecy and wrote in 1531, “John Hus prophesied of me when he wrote from his prison in Bohemia: They will now roast a goose (for Hus means a goose), but after a hundred years they will hear a swan sing; him they will have to tolerate. And so it shall continue, if it please God.”5

And so it has continued. The great voices of grace sing on today. And I count it a great joy to listen and to echo their song in this little book and, God willing, the ones to follow.

Although these chapters on Augustine, Luther, and Calvin were originally given as biographical messages at the annual Bethlehem Conference for Pastors, there is a reason why I put them together here for a wider audience including laypeople. Their combined message is profoundly relevant in this modern world at the beginning of a new millennium. R. C. Sproul is right that “we need an Augustine or a Luther to speak to us anew lest the light of God’s grace be not only overshadowed but be obliterated in our time.”6 Yes, and perhaps the best that a cricket can do is to let the swans sing.

Augustine’s song of grace is unlike anything you will read in almost any modern book about grace. The omnipotent power of grace, for Augustine, is the power of “sovereign joy.” This alone delivered him from a lifetime of bondage to sexual appetite and philosophical pride. Discovering that beneath the vaunted powers of human will is a cauldron of desire holding us captive to irrational choices opens the way to see grace as the triumph of “sovereign joy.” Oh, how we need the ancient biblical insight of Augustine to free us from the pleasant slavery that foils the fulfillment of the Great Commandment and the finishing of the Great Commission.

I am not sure that Martin Luther and John Calvin saw the conquering grace of “sovereign joy” as clearly as Augustine. But what they saw even more clearly was the supremacy of the word of God over the church and the utter necessity of sacred study at the spring of truth. Luther found his way into paradise through the gate of New Testament Greek, and Calvin bequeathed to us a five-hundred-year legacy of God-entranced preaching because his eyes were opened to see the divine majesty of the word. My prayer in writing this book is that, once we see Augustine’s vision of grace as “sovereign joy,” the lessons of Luther’s study will strengthen it by the word of God, and the lessons of Calvin’s preaching will spread it to the ends of the earth. This is The Legacy of Sovereign Joy.

Augustine “never wrote what could be called a treatise on prayer.”7Instead, his writing flows in and out of prayer. This is because, for him, “the whole life of a good Christian is a holy desire.”8 And this desire is for God, above all things and in all things. This is the desire I write to awaken and sustain. And therefore I pray with Augustine for myself and for you, the reader,

Turn not away your face from me, that I may find what I seek. Turn not aside in anger from your servant, lest in seeking you I run toward something else. . . . Be my helper. Leave me not, neither despise me, O God my Savior. Scorn not that a mortal should seek the Eternal.9

1 Peter Brown, Augustine of Hippo (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1969), 408.

2 R. C. Sproul, “Augustine and Pelagius,” in Tabletalk, June 1996: 11. See the introduction in this book (page 33, note 24) for a similar statement from Benjamin Warfield. See chapter 1 on the meaning of Pelagianism (page 45).

3 Erwin Weber, “Luther with the Swan,” The Lutheran Journal 65, no. 2 (1996): 10.

4 Ibid.

5 Martin Luther, quoted in Ewald M. Plass, What Luther Says, An Anthology (St. Louis: Concordia, 1959), 3:1175.

6 Sproul, “Augustine and Pelagius,” 52.

7 Thomas A. Hand, Augustine on Prayer (New York: Catholic Book, 1986), 11.

8 Ibid., 20.

9 Ibid., 27.

Book 1

Acknowledgments

How thankful I am for a wife and children who, several weeks each year (at least), unbegrudgingly let me live in another century. This is where I go to prepare the biographical messages for the Bethlehem Conference for Pastors. All the while, Jon Bloom, the director of Desiring God Ministries, is masterfully managing a thousand details that bring hundreds of hungry shepherds together in the dead of winter in Minneapolis. That conference, those biographies, and this book would not exist without him and the hundreds of Bethlehem volunteers who respond to his call each year.

To steal away into the Blue Ridge Mountains for a season to put this book together in its present form has been a precious gift. I owe this productive seclusion to the hospitality of the team of God’s servants at the Billy Graham Training Center at The Cove. May God grant the dream of Dr. Graham to flourish from this place—that those who attend the seminars at The Cove “will leave here transformed and prepared for action—equipped to be an effective witness for Christ.”

A special word of thanks to Lane Dennis of Crossway for his interest in these biographical studies and his willingness to make them available to a wider audience. And thanks to Carol Steinbach again for her help with this project.

Finally, I thank Jesus Christ for giving to the church teachers like St. Augustine, Martin Luther, and John Calvin. “He gave some . . . pastors and teachers, for the equipping of the saints for the work of service, to the building up of the body of Christ” (Eph. 4:11–12). I am the beneficiary of this great work of equipping the saints that these three have done for centuries. Thank you, Father, that the swans are not silent. May their song of triumphant grace continue to be sung in The Legacy of Sovereign Joy.

This will be written for the generation to come,

That a people yet to be created may praise the Lord.

Psalm 102:18

One generation shall praise Your works to another,

And shall declare Your mighty acts.

Psalm 145:4

Book 1

Introduction

Savoring the Sovereignty of Grace in the Lives of Flawed Saints

The Point of History

God ordains that we gaze on his glory, dimly mirrored in the ministry of his flawed servants. He intends for us to consider their lives and peer through the imperfections of their faith and behold the beauty of their God. “Remember your leaders, those who spoke to you the word of God; consider the outcome of their life, and imitate their faith” (Heb. 13:7 RSV). The God who fashions the hearts of all men (Ps. 33:15) means for their lives to display his truth and his worth. From Phoebe to St. Francis, the divine plan—even spoken of the pagan Pharaoh—holds firm for all: “I have raised you up for the very purpose of showing my power in you, so that my name may be proclaimed in all the earth” (Rom. 9:17 RSV). From David the king to David Brainerd, the missionary, extraordinary and incomplete specimens of godliness and wisdom have kindled the worship of sovereign grace in the hearts of reminiscing saints. “This will be written for the generation to come, that a people yet to be created may praise the Lord” (Ps. 102:18).

The history of the world is a field strewn with broken stones, which are sacred altars designed to waken worship in the hearts of those who will take the time to read and remember. “I shall remember the deeds of the Lord; surely I will remember Your wonders of old. I will meditate on all Your work and muse on Your deeds. Your way, O God, is holy; what god is great like our God?” (Ps. 77:11–13). The aim of providence in the history of the world is the worship of the people of God. Ten thousand stories of grace and truth are meant to be remembered for the refinement of faith and the sustaining of hope and the guidance of love. “Whatever was written in former days was written for our instruction, that by steadfastness and by the encouragement of the scriptures we might have hope” (Rom. 15:4 RSV). Those who nurture their hope in the history of grace will live their lives to the glory of God. That is the aim of this book.

It is a book about three famous and flawed fathers in the Christian church. Therefore, it is a book about grace, not only because the faithfulness of God triumphs over the flaws of men, but also because this was the very theme of their lives and work. Aurelius Augustine (354–430), Martin Luther (1483–1546), and John Calvin (1509–1564) had this in common: they experienced, and then built their lives and ministries on, the reality of God’s omnipotent grace. In this way their common passion for the supremacy of God was preserved from the taint of human competition. Each of them confessed openly that the essence of experiential Christianity is the glorious triumph of grace over the guilty impotence of man.

Augustine’s Discovery of “Sovereign Joy”

At first Augustine resisted the triumph of grace as an enemy. But then, in a garden in Milan, Italy, when he was thirty-one, the power of grace through the truth of God’s word broke fifteen years of bondage to sexual lust and living with a concubine. His resistance was finally overcome by “sovereign joy,” the beautiful name he gave to God’s grace. “How sweet all at once it was for me to be rid of those fruitless joys which I had once feared to lose . . . ! You drove them from me, you who are the true, the sovereign joy. You drove them from me and took their place, you who are sweeter than all pleasure. . . . O Lord my God, my Light, my Wealth, and my Salvation.”1

Then, in his maturity and to the day of his death, Augustine fought the battle for grace as a submissive captive to “sovereign joy” against his contemporary and arch-antagonist, the British monk Pelagius. Nothing shocked Pelagius more than the stark declaration of omnipotent grace in Augustine’s prayer: “Command what you wish, but give what you command.”2Augustine knew that his liberty from lust and his power to live for Christ and his understanding of biblical truth hung on the validity of that prayer. He was painfully aware of the hopelessness of leaning on free will as a help against lust.

Who is not aghast at the sudden crevasses that might open in the life of a dedicated man? When I was writing this, we were told that a man of 84, who had lived a life of continence under religious observance with a pious wife for 25 years, has gone and bought himself a music-girl for his pleasure. . . . If the angels were left to their own free-will, even they might lapse, and the world be filled with “new devils.”3

Augustine knew that the same would happen to him if God left him to lean on his own free will for faith and purity. The battle for omnipotent grace was not theoretical or academic; it was practical and pressing. At stake was holiness and heaven. Therefore he fought with all his might for the supremacy of grace against the Pelagian exaltation of man’s ultimate self-determination.4

Luther’s Pathway into Paradise

For Martin Luther, the triumph of grace came not in a garden but in a study, and not primarily over lust but over the fear of God’s wrath. “If I could believe that God was not angry with me, I would stand on my head for joy.”5 He might have said “sovereign joy.” But he could not believe it. And the great external obstacle was not a concubine in Milan, Italy, but a biblical text in Wittenberg, Germany. “A single word in [Rom. 1:17], ‘In [the gospel] the righteousness of God is revealed’ . . . stood in my way. For I hated that word ‘righteousness of God.’”6 He had been taught that the “righteousness of God” meant the justice “with which God is righteous and punishes the unrighteous sinner.”7This was no relief and no gospel. Whereas Augustine “tore [his] hair and hammered [his] forehead with his fists” in hopelessness over bondage to sexual passion,8Luther “raged with a fierce and troubled conscience . . . [and] beat importunately upon Paul at that place [Rom. 1:17], most ardently desiring to know what St. Paul wanted.”9

The breakthrough came in 1518, not, as with Augustine, by the sudden song of a child chanting, “Take it and read,”10 but by the unrelenting study of the historical-grammatical context of Romans 1:17. This sacred study proved to be a precious means of grace. “At last, by the mercy of God, meditating day and night, I gave heed to the context of the words, namely . . . ‘He who through faith is righteous shall live.’ There I began to understand [that] the righteousness of God is that by which the righteous lives by a gift of God, namely by faith. . . . Here I felt that I was altogether born again and had entered paradise itself through open gates.”11 This was the joy that turned the world upside-down.

Justification by faith alone, apart from works of the law, was the triumph of grace in the life of Martin Luther. He did, you might say, stand on his head for joy, and with him all the world was turned upside-down. But the longer he lived, the more he was convinced that there was a deeper issue beneath this doctrine and its conflict with the meritorious features of indulgences12 and purgatory. In the end, it was not Johann Tetzel’s sale of indulgences or Johann Eck’s promotion of purgatory that produced Luther’s most passionate defense of God’s omnipotent grace; it was Desiderius Erasmus’s defense of free will.

Erasmus was to Luther what Pelagius was to Augustine. Martin Luther conceded that Erasmus, more than any other opponent, had realized that the powerlessness of man before God, not the indulgence controversy or purgatory, was the central question of the Christian faith.13 Luther’s book The Bondage of the Will, published in 1525, was an answer to Erasmus’s book The Freedom of the Will. Luther regarded this one book of his—The Bondage of the Will—as his “best theological book, and the only one in that class worthy of publication.”14 This is because at the heart of Luther’s theology was a total dependence on the freedom of God’s omnipotent grace to rescue powerless man from the bondage of the will. “Man cannot by his own power purify his heart and bring forth godly gifts, such as true repentance for sins, a true, as over against an artificial, fear of God, true faith, sincere love. . . .”15 Erasmus’s exaltation of man’s fallen will as free to overcome its own sin and bondage was, in Luther’s mind, an assault on the freedom of God’s grace and therefore an attack on the very gospel itself, and ultimately on the glory of God. Thus Luther proved himself to be a faithful student of St. Augustine and St. Paul to the very end.

Calvin’s Encounter with the Divine Majesty of the Word

For John Calvin, the triumph of God’s grace in his own life and theology was the self-authenticating demonstration of the majesty of God in the word of Scripture. How are we to know that the Bible is the word of God? Do we lean on the testimony of man—the authority of the church, as in Roman Catholicism? Or are we more immediately dependent on the majesty of God’s grace? Sometime in his early twenties, before 1533, at the University of Paris, Calvin’s resistance to grace was conquered for the glory of God and for the cause of the Reformation. “God, by a sudden conversion subdued and brought my mind to a teachable frame. . . . Having thus received some taste and knowledge of true godliness, I was immediately inflamed with [an] intense desire to make progress.”16With this “taste” and this “intense desire,” the legacy of sovereign joy took root in another generation.

The power that “subdued” his mind was the manifestation of the majesty of God. “Our Heavenly Father, revealing his majesty [in Scripture], lifts reverence for Scripture beyond the realm of controversy.”17 There is the key for Calvin: the witness of God to Scripture is the immediate, unassailable, life-giving revelation to our minds of the majesty of God that is manifest in the Scriptures themselves. This was his testimony to the omnipotent grace of God in his life: the blind eyes of his spirit were opened, and what he saw immediately, and without a lengthy chain of human reasoning, were two things so interwoven that they would determine the rest of his life—the majesty of God and the word of God. The word mediated the majesty, and the majesty vindicated the word. Henceforth he would be a man utterly devoted to displaying the supremacy of God’s glory by the exposition of God’s word.

United with a Passion for the Supremacy of Divine Grace

In all of this, Augustine, Luther, and Calvin were one. Their passion was to display above all things the glory of God through the exaltation of his omnipotent grace. Augustine’s entire life was one great “confession” of the glory of God’s grace: “O Lord, my Helper and my Redeemer, I shall now tell and confess to the glory of your name how you released me from the fetters of lust which held me so tightly shackled and from my slavery to the things of this world.”18 From the beginning of Luther’s discovery of grace, displaying the glory of God was the driving force of his labor. “I recall that at the beginning of my cause Dr. Staupitz, who was then a man of great importance and vicar of the Augustinian Order, said to me: ‘It pleases me that the doctrine which you preach ascribes the glory and everything to God alone and nothing to man.’”19 Calvin’s course was fixed from his first dispute with Cardinal Sadolet in 1539 when he charged the Cardinal to “set before [man], as the prime motive of his existence, zeal to illustrate the glory of God.”20

Under Christ, Augustine’s influence on Luther and Calvin was second only to the influence of the apostle Paul. Augustine towers over the thousand years between himself and the Reformation, heralding the sovereign joy of God’s triumphant grace for all generations. Adolf Harnack said that he was the greatest man “between Paul the Apostle and Luther the Reformer, the Christian Church has possessed.”21 The standard text on theology that Calvin and Luther drank from was Sentences by Peter Lombard. Nine-tenths of this book consists of quotations from Augustine, and it was for centuries the textbook for theological studies.22 Luther was an Augustinian monk, and Calvin immersed himself in the writings of Augustine, as we can see from the increased use of Augustine’s writings in each new edition of the Institutes. “In the 1536 edition of the Institutes he quotes Augustine 20 times, three years later 113, in 1543 it was 128 times, 141 in 1550 and finally, no less than 342 in 1559.”23

Not surprisingly, therefore, yet paradoxically, one of the most esteemed fathers of the Roman Catholic Church “gave us the Reformation.” Benjamin Warfield put it like this: “The Reformation, inwardly considered, was just the ultimate triumph of Augustine’s doctrine of grace over Augustine’s doctrine of the Church.”24 In other words, there were tensions within Augustine’s thought that explain why he could be cited by both Roman Catholics and by Reformers as a champion.

God’s Grace over the Flaws of Great Saints

This brings us back to an earlier point. This book, which is about Augustine, Luther, and Calvin, is a book about the glory of God’s omnipotent grace, not only because it was the unifying theme of their work, but also because this grace triumphed over the flaws in these men’s lives. Augustine’s most famous work is called the Confessions in large measure because his whole ministry was built on the wonder that God could forgive and use a man who had sold himself to so much sensuality for so long. And now we add to this imperfection the flaws of Augustine’s theology suggested by Warfield’s comment that his doctrine of grace triumphed over his doctrine of the church. Of course, this will be disputed. But from my perspective he is correct to draw attention to Augustine’s weaknesses amid massive strengths.

Augustine’s Dubious Record on Sex and Sacraments

For example, it is a perplexing incongruity that Augustine would exalt the free and sovereign grace of God so supremely and yet hold to a view of baptism that makes the act of man so decisive in the miracle of regeneration. Baptismal regeneration and spiritual awakening by the power of the word of God do not fit together. The way Augustine speaks of baptism seems to go against his entire experience of God’s grace, awakening and transforming him through the word of God in Milan. In the Confessions he mentions a friend who was baptized while unconscious and comes to his senses changed.25 “In a way that Augustine never claimed to understand, the physical rites of baptism and ordination ‘brand’ a permanent mark on the recipient, quite independent of his conscious qualities.”26 He regretted not having been baptized as a youth and believed that ritual would have spared him much misery. “It would have been much better if I had been healed at once and if all that I and my family could do had been done to make sure that once my soul had received its salvation, its safety should be left in your keeping, since its salvation had come from you. This would surely have been the better course.”27 Peter Brown writes that Augustine “had once hoped to understand the rite of infant baptism: ‘Reason will find that out.’ Now he will appeal, not to reason, but to the rooted feelings of the Catholic masses.”28

Of course, Augustine is not alone in mingling a deep knowledge of grace with defective views and flawed living. Every worthy theologian and every true saint does the same. Every one of them confesses, “Now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face; now I know in part, but then I shall know fully just as I also have been fully known” (1 Cor. 13:12). “Not that I have already obtained it, or have already become perfect, but I press on so that I may lay hold of that for which also I was laid hold of by Christ Jesus” (Phil. 3:12). But the famous flawed saints have their flaws exposed and are criticized vigorously for it.

Diverse Defects of Different Men

Martin Luther and John Calvin were seriously flawed saints. The flaws grew in the soil of very powerful—and very different—personalities.

How different the upbringing of the two men—the one, the son of a German miner, singing for his livelihood under the windows of the well-to-do burghers; the other, the son of a French procurator-fiscal, delicately reared and educated with the children of the nobility. How different, too, their temperaments—Luther, hearty, jovial, jocund, sociable, filling his goblet day by day from the Town Council’s wine-cellar; Calvin, lean, austere, retiring, given to fasting and wakefulness. . . . Luther was a man of the people, endowed with passion, poetry, imagination, fire, whereas Calvin was cold, refined, courteous, able to speak to nobles and address crowned heads, and seldom, if ever, needing to retract or even to regret his words.29

Luther’s Dirty Mouth and Lapse of Love

But, oh, how many words did Luther regret! This was the downside of a delightfully blunt and open emotional life, filled with humor as well as anger. Heiko Oberman refers to Luther’s “jocular theologizing.”30 “If I ever have to find myself a wife again, I will hew myself an obedient wife out of stone.”31 “In domestic affairs I defer to Katie. Otherwise I am led by the Holy Ghost.”32“I have legitimate children, which no papal theologian has.”33 His personal experience is always present. “With Luther feelings force their way everywhere. . . . He himself is passionately present, not only teaching life by faith but living faith himself.”34 This makes him far more interesting and attractive as a person than Calvin, but far more volatile and offensive—depending on what side of the joke you happen to be on. We cannot imagine today (as much as we might like to) a university professor doing theology the way Luther did it. The leading authority on Luther comments, “[Luther] would look in vain for a chair in theology today at Harvard. . . . It is the Erasmian type of ivory-tower academic that has gained international acceptance.”35

With all its spice, his language could also move toward crudity and hatefulness. His longtime friend Melanchthon did not hesitate to mention Luther’s “sharp tongue” and “heated temper” even as he gave his funeral oration.36 There were also the four-letter words and the foul “bathroom” talk. He confessed from time to time that it was excessive. “Many accused me of proceeding too severely. Severely, that is true, and often too severely; but it was a question of the salvation of all, even my opponents.”37

We who are prone to fault him for his severity and mean-spirited language can scarcely imagine what the battle was like in those days, and what it was like to be the target of so many vicious, slanderous, and life-threatening attacks. “He could not say a word that would not be heard and pondered everywhere.”38 It will be fair to let Luther and one of his balanced admirers put his harshness and his crudeness in perspective. First Luther himself:

I own that I am more vehement than I ought to be; but I have to do with men who blaspheme evangelical truth; with human wolves; with those who condemn me unheard, without admonishing, without instructing me; and who utter the most atrocious slanders against myself not only, but the Word of God. Even the most phlegmatic spirit, so circumstanced, might well be moved to speak thunderbolts; much more I who am choleric by nature, and possessed of a temper easily apt to exceed the bounds of moderation.

I cannot, however, but be surprised to learn whence the novel taste arose which daintily calls everything spoken against an adversary abusive and acrimonious. What think ye of Christ? Was he a reviler when he called the Jews an adulterous and perverse generation, a progeny of vipers, hypocrites, children of the devil?

What think you of Paul? Was he abusive when he termed the enemies of the gospel dogs and seducers? Paul who, in the thirteenth chapter of the Acts, inveighs against a false prophet in this manner: “Oh, full of subtlety and all malice, thou child of the devil, thou enemy of all righteousness.” I pray you, good Spalatin, read me this riddle. A mind conscious of truth cannot always endure the obstinate and willfully blind enemies of truth. I see that all persons demand of me moderation, and especially those of my adversaries, who least exhibit it. If I am too warm, I am at least open and frank; in which respect I excel those who always smile, but murder.39

It may seem futile to ponder the positive significance of filthy language, but let the reader judge whether “the world’s foremost authority on Luther”40 helps us grasp a partially redemptive purpose in Luther’s occasionally foul mouth.

Luther’s scatology-permeated language has to be taken seriously as an expression of the painful battle fought body and soul against the Adversary, who threatens both flesh and spirit. . . . The filthy vocabulary of Reformation propaganda [was] aimed at inciting the common man. . . . Luther used a great deal of invective, but there was method in it. . . . Inclination and conviction unite to form a mighty alliance, fashioning a new language of filth which is more than filthy language. Precisely in all its repulsiveness and perversion it verbalizes the unspeakable: the diabolic profanation of God and man. Luther’s lifelong barrage of crude words hurled at the opponents of the Gospel is robbed of significance if attributed to bad breeding. When taken seriously, it reveals the task Luther saw before him: to do battle against the greatest slanderer of all times!41

Nevertheless most will agree that even though the thrust and breakthrough of the Reformation against such massive odds required someone of Luther’s forcefulness, a line was often crossed into unwarranted invective and sin. Heiko Oberman is surely right to say, “Where resistance to the Papal State, fanaticism, and Judaism turns into the collective vilification of papists, Anabaptists, and Jews, the fatal point has been reached where the discovery of the Devil’s power becomes a liability and a danger.”42 Luther’s sometimes malicious anti-Semitism was an inexcusable contradiction of the gospel he preached. Oberman observes with soberness and depth that Luther aligned himself with the Devil here, and the lesson to be learned is that this is possible for Christians, and to demythologize it is to leave Luther’s anti-Semitism in the hands of modern unbelief with no weapon against it.43 In other words, the Devil is real and can trip a great man into graceless behavior, even as he recovers grace from centuries of obscurity.

Calvin’s Accommodation to Brutal Times

John Calvin was very different from Luther but just as much a child of his harsh and rugged age. He and Luther never met, but they had profound respect for each other. When Luther read Calvin’s defense of the Reformation to Cardinal Sadolet in 1539, he said, “Here is a writing which has hands and feet. I rejoice that God raises up such men.”44 Calvin returned the respect in the one letter to Luther that we know of, which Luther did not receive. “Would that I could fly to you that I might, even for a few hours, enjoy the happiness of your society; for I would prefer, and it would be far better . . . to converse personally with yourself; but seeing that it is not granted to us on earth, I hope that shortly it will come to pass in the kingdom of God.”45 Knowing their circumstances better than we, and perhaps knowing their own sins better than we, they could pass over each other’s flaws more easily in their affections.

It has not been so easy for others. The greatness of the accolades for John Calvin have been matched by the seriousness and severity of the criticisms. In his own day, even his brilliant contemporaries stood in awe of Calvin’s grasp of the fullness of Scripture. At the 1541 Conference at Worms, Melanchthon expressed that he was overwhelmed at Calvin’s learning and called him simply “The Theologian.” In modern times, T. H. L. Parker agrees and says, “Augustine and Luther were perhaps his superiors in creative thinking; Aquinas in philosophy; but in systematic theology Calvin stands supreme.”46 And Benjamin Warfield said, “No man ever had a profounder sense of God than he.”47 But the times were barbarous, and not even Calvin could escape the evidences of his own sinfulness and the blind spots of his own age.

Life was harsh, even brutal, in the sixteenth century. There was no sewer system or piped water supply or central heating or refrigeration or antibiotics or penicillin or aspirin or surgery for appendicitis or Novocain for tooth extraction or electric lights for studying at night or water heaters or washers or dryers or stoves or ballpoint pens or typewriters or computers. Calvin, like many others in his day, suffered from “almost continuous ill-health.”48 If life could be miserable physically, it could get even more dangerous socially and more grievous morally. The libertines in Calvin’s church, like their counterparts in first-century Corinth, reveled in treating the “communion of saints” as a warrant for wife-swapping.49 Calvin’s opposition made him the victim of mob violence and musket fire more than once.

Not only were the times unhealthy, harsh, and immoral, they were often barbaric as well. This is important to see, because Calvin did not escape the influence of his times. He described in a letter the cruelty common in Geneva. “A conspiracy of men and women has lately been discovered who, for the space of three years, had [intentionally] spread the plague through the city, by what mischievous device I know not.” The upshot of this was that fifteen women were burned at the stake. “Some men,” Calvin said, “have even been punished more severely; some have committed suicide in prison, and while twenty-five are still kept prisoners, the conspirators do not cease . . . to smear the door-locks of the dwelling-houses with their poisonous ointment.”50

This kind of capital punishment loomed on the horizon not just for criminals, but for the Reformers themselves. Calvin was driven out of his homeland, France, under threat of death. For the next twenty years, he agonized over the martyrs there and corresponded with many of them as they walked faithfully toward the stake. The same fate easily could have befallen Calvin with the slightest turn in providence. “We have not only exile to fear, but that all the most cruel varieties of death are impending over us, for in the cause of religion they will set no bounds to their barbarity.”51

This atmosphere gave rise to the greatest and the worst achievement of Calvin. The greatest was the writing of the Institutes of the Christian Religion, and the worst was his joining in the condemnation of the heretic Michael Servetus to burning at the stake in Geneva. The Institutes was first published in March 1536, when Calvin was twenty-six years old. It went through five editions and enlargements until it reached its present form in the 1559 edition. If this were all Calvin had written—and not forty-eight volumes of other works—it would have established him as the foremost theologian of the Reformation. But the work did not arise for merely academic reasons. We will see in chapter 3 that it arose in tribute and defense of Protestant martyrs in France.52

But it was this same cruelty from which he could not disentangle himself. Michael Servetus was a Spaniard, a medical doctor, a lawyer, and a theologian. His doctrine of the Trinity was unorthodox—so much so that it shocked both Catholic and Protestant in his day. In 1553, he published his views and was arrested by the Catholics in France. But, alas, he escaped to Geneva. He was arrested there, and Calvin argued the case against him. He was sentenced to death. Calvin called for a swift execution instead of burning, but Servetus was burned at the stake on October 27, 1553.53

This has tarnished Calvin’s name so severely that many cannot give his teaching a hearing. But it is not clear that most of us, given that milieu, would not have acted similarly under the circumstances.54 Melanchthon was the gentle, soft-spoken associate of Martin Luther whom Calvin had met and loved. He wrote to Calvin on the Servetus affair, “I am wholly of your opinion and declare also that your magistrates acted quite justly in condemning the blasphemer to death.”55 Calvin never held civil office in Geneva56 but exerted all his influence as a pastor. Yet in this execution, his hands were as stained with Servetus’s blood as David’s were with Uriah’s.

This makes the confessions of Calvin near the end of his life all the more important. On April 25, 1564, a month before his death, he called the magistrates of the city to his room and spoke these words:

With my whole soul I embrace the mercy which [God] has exercised towards me through Jesus Christ, atoning for my sins with the merits of his death and passion, that in this way he might satisfy for all my crimes and faults, and blot them from his remembrance. . . . I confess I have failed innumerable times to execute my office properly, and had not he, of his boundless goodness, assisted me, all that zeal had been fleeting and vain. . . . For all these reasons, I testify and declare that I trust to no other security for my salvation than this, and this only, viz., that as God is the Father of mercy, he will show himself such a Father to me, who acknowledge myself to be a miserable sinner.57

T. H. L. Parker said, “He should never have fought the battle of faith with the world’s weapons.”58 Most of us today would agree. Whether Calvin came to that conclusion before he died, we don’t know. But what we know is that Calvin knew himself a “miserable sinner” whose only hope in view of “all [his] crimes” was the mercy of God and the blood of Jesus.

Why We Need the Flawed Fathers

So the times were harsh, immoral, and barbarous and had a contaminating effect on everyone, just as we are all contaminated by the evils of our own time. Their blind spots and evils may be different from ours. And it may be that the very things they saw clearly are the things we are blind to. It would be naïve to say that we never would have done what they did under their circumstances, and thus draw the conclusion that they have nothing to teach us. In fact, we are, no doubt, blind to many of our evils, just as they were blind to many of theirs. The virtues they manifested in those times are probably the very ones that we need in ours. There was in the life and ministry of John Calvin a grand God-centeredness, Bible-allegiance, and iron constancy. Under the banner of God’s mercy to miserable sinners, we would do well to listen and learn. And that goes for Martin Luther and St. Augustine as well.

The conviction behind this book is that the glory of God, however dimly, is mirrored in the flawed lives of his faithful servants. God means for us to consider their lives and peer through the imperfections of their faith and behold the beauty of their God. This is what I hope will happen through the reading of this book. There are life-giving lessons written by the hand of Divine Providence on every page of history. The great German and the great Frenchman drank from the great African, and God gave the life of the Reformation.

But let us be admonished, finally, from the mouth of Luther that the only original, true, and life-giving spring is the word of God. Beware of replacing the pure mountain spring of Scripture with the sullied streams of great saints. They are precious, but they are not pure. So we say with Luther,

The writings of all the holy fathers should be read only for a time, in order that through them we may be led to the Holy Scriptures. As it is, however, we read them only to be absorbed in them and never come to the Scriptures. We are like men who study the sign-posts and never travel the road. The dear fathers wished by their writing, to lead us to the Scriptures, but we so use them as to be led away from the Scriptures, though the Scriptures alone are our vineyard in which we ought all to work and toil.59

I hope it will be plain, by the focus and development of the following three chapters, that this is the design of the book: From the “Sovereign Joy” of grace discovered by Augustine to the “Sacred Study” of Scripture in the life of Luther to the “Divine Majesty of the Word” in the life and preaching of Calvin, the aim is that the glorious gospel of God’s all-satisfying, omnipotent grace will be savored, studied, and spread for the joy of all peoples—in a never-ending legacy of sovereign joy. And so may the Lord come quickly.

1 Augustine, Confessions, trans. R. S. Pine-Coffin (New York: Penguin, 1961), 181 (IX, 1), emphasis added.

2 Peter Brown, Augustine of Hippo (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1969), 179. The quote is found in Augustine, Confessions, 40 (X, 29).

3Contra Julian, III, x, 22, quoted in Brown, Augustine of Hippo, 405.

4 The book Augustine himself saw as his “most fundamental demolition of Pelagianism” (Brown, Augustine of Hippo, 372) is On the Spirit and the Letter, in Augustine: Later Works, ed. John Burnaby (Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press, 1965), 182–251.

5 Heiko A. Oberman, Luther: Man between God and the Devil, trans. Eileen Walliser-Schwarzbart (orig. 1982; New York: Doubleday, 1992), 315.

6 John Dillenberger, ed., Martin Luther: Selections from His Writings (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1961), 11, emphasis added.

7 Ibid.

8 “I was beside myself with madness that would bring me sanity. I was dying a death that would bring me life. . . . I was frantic, overcome by violent anger with myself for not accepting your will and entering into your covenant. . . . I tore my hair and hammered my forehead with my fists; I locked my fingers and hugged my knees.” Augustine, Confessions, 170–71 (VIII, 8).

9 Dillenberger, Martin Luther: Selections, 12.

10 See chapter 1 of this book for the details of this remarkable story.

11 Dillenberger, Martin Luther: Selections, 12.

12 Indulgences were the sale of release from temporal punishment for sin through the payment of money to the Roman Catholic Church—for yourself or another in purgatory.

13 Oberman, Luther: Man between God and the Devil, 220.

14 Dillenberger, Martin Luther: Selections, 167.

15 Conrad Bergendoff, ed.,